Opioid use disorder

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a substance use disorder characterized by cravings for opioids, continued use despite physical and/or psychological deterioration, increased tolerance with use, and withdrawal symptoms after discontinuing opioids.[12] Opioid withdrawal symptoms include nausea, muscle aches, diarrhea, trouble sleeping, agitation, and a low mood.[13][5] Addiction and dependence are important components of opioid use disorder.[14]

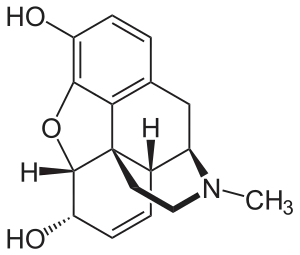

| Opioid use disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Opioid addiction,[1] problematic opioid use,[1] opioid abuse,[2] opioid dependence[3] |

| |

| Molecular structure of morphine | |

| Specialty | Addiction medicine, psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Strong desire to use opioids, increased tolerance to opioids, failure to meet obligations, trouble with reducing use, withdrawal syndrome with discontinuation[4][5] |

| Complications | Opioid overdose, hepatitis C, marriage problems, unemployment, poverty[4][5] |

| Duration | Long term[6] |

| Causes | Opioids[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on criteria in the DSM-5[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Alcoholism |

| Treatment | Opioid replacement therapy, behavioral therapy, twelve-step programs, take home naloxone[7][8][9] |

| Medication | Buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone[7][10] |

| Frequency | 16 million [11] |

| Deaths | 120,000 [11] |

Risk factors include a history of opioid misuse, current opioid misuse, young age, socioeconomic status, race, untreated psychiatric disorders, and environments that promote misuse (social, family, professional, etc.).[15][16] Complications may include opioid overdose, suicide, HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C, and problems meeting social or professional responsibilities.[5][4] Diagnosis may be based on criteria by the American Psychiatric Association in the DSM-5.[4]

Opioids include substances such as heroin, morphine, fentanyl, codeine, dihydrocodeine, oxycodone, and hydrocodone.[5][6] A useful standard for the relative strength of different opioids is morphine milligram equivalents (MME).[17] It is recommended for clinicians to refer to daily MMEs when prescribing opioids to decrease the risk of misuse and adverse effects.[18]

opiates and opioids

opiates and opioids MME of common opioids

MME of common opioids

Long-term opioid use occurs in about 4% of people following their use for trauma or surgery-related pain.[19] In the United States, most heroin users begin by using prescription opioids that may also be bought illegally.[20][21]

People with an opioid use disorder are often treated with opioid replacement therapy using methadone or buprenorphine.[22] Such treatment reduces the risk of death.[22] Additionally, they may benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy, other forms of support from mental health professionals such as individual or group therapy, twelve-step programs, and other peer support programs.[23] The medication naltrexone may also be useful to prevent relapse.[10][8] Naloxone is useful for treating an opioid overdose and giving those at risk naloxone to take home is beneficial.[24] In 2020, the CDC estimated that nearly 3 million people in the U.S. were living with OUD and more than 65,000 people died by opioid overdose, of whom more than 15,000 were heroin overdoses.[25][26]

Diagnosis

The DSM-5 guidelines for the diagnosis of opioid use disorder require that the individual has a significant impairment or distress related to opioid uses.[4] To make the diagnosis two or more of 11 criteria must be present in a given year:[4]

- More opioids are taken than intended

- The individual is unable to decrease the number of opioids used

- Large amounts of time are spent trying to obtain opioids, use opioids, or recover from taking them

- The individual has cravings for opioids

- Difficulty fulfilling professional duties at work or school

- Continued use of opioids leading to social and interpersonal consequences

- Decreased social or recreational activities

- Using opioids despite being in physically dangerous settings

- Continued use despite opioids worsening physical or psychological health (i.e. depression, constipation)

- Tolerance

- Withdrawal

The severity can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on the number of criteria present.[6] The tolerance and withdrawal criteria are not considered to be met for individuals taking opioids solely under appropriate medical supervision.[4] Addiction and dependence are components of a substance use disorder; addiction is the more severe form.[14]

Signs and symptoms

Opioid intoxication

Signs and symptoms of opioid intoxication include:[5][27]

- Decreased perception of pain

- Euphoria

- Confusion

- Desire to sleep

- Nausea

- Constipation

- Miosis (pupil constriction)

- Bradycardia (slow heart rate)

- Hypotension (low blood pressure)

- Hypokinesis (slowed movement)

- Head nodding

- Slurred speech

- Hypothermia (low body temperature)

Opioid overdose

Signs and symptoms of opioid overdose include, but are not limited to:[29]

- Pin-point pupils may occur. Patient presenting with dilated pupils may still be experiencing an opioid overdose.

- Decreased heart rate

- Decreased body temperature

- Decreased breathing

- Altered level of consciousness. People may be unresponsive or unconscious.

- Pulmonary edema (fluid accumulation in the lungs)

- Shock

- Death

Withdrawal

Opioid withdrawal can occur with a sudden decrease in, or cessation of, opioids after prolonged use.[30][31] Onset of withdrawal depends on the half-life of the opioid that was used last.[32] With heroin this typically occurs five hours after use; with methadone, it may take two days.[32] The length of time that major symptoms occur also depends on the opioid used.[32] For heroin withdrawal, symptoms are typically greatest at two to four days and can last up to two weeks.[33][32] Less significant symptoms may remain for an even longer period, in which case the withdrawal is known as post-acute-withdrawal syndrome.[32]

Treatment of withdrawal may include methadone and buprenorphine. Medications for nausea or diarrhea may also be used.[31]

Cause

Opioid use disorder can develop as a result of self-medication.[34] Scoring systems have been derived to assess the likelihood of opiate addiction in chronic pain patients.[35] Healthcare practitioners have long been aware that despite the effective use of opioids for managing pain, empirical evidence supporting long-term opioid use is minimal.[36][37][38][39][40] Many studies of patients with chronic pain have failed to show any sustained improvement in their pain or ability to function with long-term opioid use.[37][41][42][43][40]

According to position papers on the treatment of opioid dependence published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the World Health Organization, care providers should not treat opioid use disorder as the result of a weak moral character or will but as a medical condition.[16][44][45] Some evidence suggests the possibility that opioid use disorders occur due to genetic or other chemical mechanisms that may be difficult to identify or change, such as dysregulation of brain circuitry involving reward and volition. But the exact mechanisms involved are unclear, leading to debate over the influence of biology and free will.[46][47]

Mechanism

Addiction

Addiction is a brain disorder characterized by compulsive drug use despite adverse consequences.[14][48][49][50] It is a component of substance use disorder and its most severe form.[14]

Overexpression of the gene transcription factor ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens plays a crucial role in the development of an addiction to opioids and other addictive drugs by sensitizing drug reward and amplifying compulsive drug-seeking behavior.[48][51][52][53] Like other addictive drugs, overuse of opioids leads to increased ΔFosB expression in the nucleus accumbens.[51][52][53][54] Opioids affect dopamine neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens via the disinhibition of dopaminergic pathways as a result of inhibiting the GABA-based projections to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) from the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg), which negatively modulate dopamine neurotransmission.[55][56] In other words, opioids inhibit the projections from the RMTg to the VTA, which in turn disinhibits the dopaminergic pathways that project from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens and elsewhere in the brain.[55][56]

The differences in the genetic regions encoding the dopamine receptors for each individual may help to elucidate part of the risk for opioid addiction and general substance abuse. Studies of the D2 Dopamine Receptor, in particular, have shown some promising results. One specific SNP is at the TaqI RFLP (rs1800497). In a study of 530 Han Chinese heroin-addicted individuals from a Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program, those with the specific genetic variation showed higher mean heroin consumption by around double those without the SNP.[57] This study helps to show the contribution of dopamine receptors to substance addiction and more specifically to opioid abuse.[57]

Neuroimaging has shown functional and structural alterations in the brain.[58] Chronic intake of opioids such as heroin may cause long-term effects in the orbitofrontal area (OFC), which is essential for regulating reward-related behaviors, emotional responses, and anxiety.[59] Moreover, neuroimaging and neuropsychological studies demonstrate dysregulation of circuits associated with emotion, stress and high impulsivity.[60]

Dependence

Opioid dependence can occur as physical dependence, psychological dependence, or both.[61] Drug dependence is an adaptive state associated with a withdrawal syndrome upon cessation of repeated exposure to a stimulus (e.g., drug intake).[48][49][50] Dependence is a component of a substance use disorder.[14][62] Opioid dependence can manifest as physical dependence, psychological dependence, or both.[61][49][62]

Increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) signaling in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) has been shown to mediate opioid-induced withdrawal symptoms via downregulation of insulin receptor substrate 2 (IRS2), protein kinase B (AKT), and mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2).[48][63] As a result of downregulated signaling through these proteins, opiates cause VTA neuronal hyperexcitability and shrinkage (specifically, the size of the neuronal soma is reduced).[48] It has been shown that when an opiate-naive person begins using opiates in concentrations that induce euphoria, BDNF signaling increases in the VTA.[64]

Upregulation of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) signal transduction pathway by cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), a gene transcription factor, in the nucleus accumbens is a common mechanism of psychological dependence among several classes of drugs of abuse.[61][48] Upregulation of the same pathway in the locus coeruleus is also a mechanism responsible for certain aspects of opioid-induced physical dependence.[61][48]

A scale was developed to compare the harm and dependence liability of 20 drugs.[65] The scale uses a rating of zero to three to rate physical dependence, psychological dependence, and pleasure to create a mean score for dependence.[65] Selected results can be seen in the chart below. Heroin and morphine both scored highest, at 3.0.[65]

| Drug | Mean | Pleasure | Psychological dependence | Physical dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heroin/Morphine | 3.00 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Cocaine | 2.39 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 1.3 |

| Alcohol | 1.93 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| Benzodiazepines | 1.83 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| Tobacco | 2.21 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

Opioid receptors

A genetic basis for the efficacy of opioids in the treatment of pain has been demonstrated for several specific variations, but the evidence for clinical differences in opioid effects is ambiguous. The pharmacogenomics of the opioid receptors and their endogenous ligands have been the subject of intensive activity in association studies. These studies test broadly for a number of phenotypes, including opioid dependence, cocaine dependence, alcohol dependence, methamphetamine dependence/psychosis, response to naltrexone treatment, personality traits, and others. Major and minor variants have been reported for every receptor and ligand coding gene in both coding sequences, as well as regulatory regions. Newer approaches shift away from analysis of specific genes and regions, and are based on an unbiased screen of genes across the entire genome, which have no apparent relationship to the phenotype in question. These GWAS studies yield a number of implicated genes, although many of them code for seemingly unrelated proteins in processes such as cell adhesion, transcriptional regulation, cell structure determination, and RNA, DNA, and protein handling/modifying.[66]

118A>G variant

While over 100 variants have been identified for the opioid mu-receptor, the most studied mu-receptor variant is the non-synonymous 118A>G variant, which results in functional changes to the receptor, including lower binding site availability, reduced mRNA levels, altered signal transduction, and increased affinity for beta-endorphin. In theory, all these functional changes would reduce the impact of exogenous opioids, requiring a higher dose to achieve the same therapeutic effect. This points to a potential for greater addictive capacity in individuals who require higher dosages to achieve pain control. But evidence linking the 118A>G variant to opioid dependence is mixed, with associations shown in a number of study groups, but negative results in other groups. One explanation for the mixed results is the possibility of other variants that are in linkage disequilibrium with the 118A>G variant and thus contribute to different haplotype patterns more specifically associated with opioid dependence.[67]

Non-opioid receptor genes

The preproenkephalin gene, PENK, encodes for the endogenous opiates that modulate pain perception, and are implicated in reward and addiction. (CA) repeats in the 3' flanking sequence of the PENK gene was associated with greater likelihood of opiate dependence in repeated studies. Variability in the MCR2 gene, encoding melanocortin receptor type 2 has been associated with both protective effects and increased susceptibility to heroin addiction. The CYP2B6 gene of the cytochrome P450 family also mediates breakdown of opioids and thus may play a role in dependence and overdose.[68]

Prevention

The CDC gives specific recommendations for prescribers regarding initiation of opioids, clinically appropriate use of opioids, and assessing possible risks associated with opioid therapy.[69] Large U.S. retail pharmacy chains are implementing protocols, guidelines, and initiatives to take back unused opioids, providing naloxone kits, and being vigilant for suspicious prescriptions.[70][71][72] Insurance programs can help limit opioid use by setting quantity limits on prescriptions or requiring prior authorizations for certain medications.[73]

Opioid-related deaths

Naloxone is used for the emergency treatment of an overdose.[74] It can be given by many routes (e.g., intramuscular, intravenous, subcutaneous, intranasal, and inhalation) and acts quickly by displacing opioids from opioid receptors and preventing the activation of these receptors.[72] Naloxone kits are recommended for laypersons who may witness an opioid overdose, for people with large prescriptions for opioids, those in substance use treatment programs, and those recently released from incarceration.[75] Since this is a life-saving medication, many areas of the U.S. have implemented standing orders for law enforcement to carry and give naloxone as needed.[76][77] In addition, naloxone can be used to challenge a person's opioid abstinence status before starting a medication such as naltrexone, which is used in the management of opioid addiction.[78]

Good Samaritan laws typically protect bystanders who administer naloxone. In the U.S., at least 40 states have Good Samaritan laws to encourage bystanders to take action without fear of prosecution.[79] As of 2019, 48 states give pharmacists the authority to distribute naloxone without an individual prescription.[80]

Homicide, suicide, accidents and liver disease are also opioid-related causes of death for those with OUD.[81][82] Many of these causes of death are unnoticed due to the often limited information on death certificates.[81][83]

Mitigation

The "CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain-United States, 2022" provides recommendations related to opioid misuse, OUD, and opioid overdoses.[84] It reports a lack of clinical evidence that "abuse-deterrent" opioids (e.g., OxyContin), as labeled by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, are effective for OUD risk mitigation.[84][85] CDC guidance suggests the prescription of immediate-release opioids instead of opioids that have a long duration (long-acting) or opioids that are released over time (extended release).[84] Other recommendations include prescribing the lowest opioid dose that successfully addresses the pain in opioid-naïve patients and collaborating with patients who already take opioid therapy to maximize the effect of non-opioid analgesics.[84]

While receiving opioid therapy, patients should be periodically evaluated for opioid-related complications and clinicians should review state prescription drug monitoring program systems.[84] The latter should be assessed to reduce the risk of overdoses in patients due to their opioid dose or medication combinations.[84] For patients receiving opioid therapy in whom the risks outweigh the benefits, clinicians and patients should develop a treatment plan to decrease their opioid dose incrementally.[84]

For more specific mitigation strategies regarding opioid overdoses, see opioid overdose § Prevention.

Management

Opioid use disorders typically require long-term treatment and care with the goal of reducing risks for the individual, reducing criminal behavior, and improving the long-term physical and psychological condition of the person.[45] Some strategies aim to reduce drug use and lead to abstinence from opioids, while others attempt to stabilize on prescribed methadone or buprenorphine with continued replacement therapy indefinitely.[45] No single treatment works for everyone, so several strategies have been developed including therapy and drugs.[45][86] There is evidence that people with opioid use disorder who are dependent on pharmaceutical opioids may require a different management approach from those who take heroin.[87]

Though treatment reduces mortality rates, the first four weeks after treatment begins and the four weeks after treatment ceases are the riskiest times for drug-related deaths.[7] These periods of increased vulnerability are significant because many of those in treatment leave programs during these periods.[7]

Medication

Opioid replacement therapy (ORT), also known as opioid substitution therapy (OST), involves replacing an opioid, such as heroin, with a longer-acting but less euphoric opioid.[88][89] Commonly used drugs for ORT are methadone and buprenorphine, which are taken under medical supervision.[89] As of 2018, buprenorphine/naloxone is preferentially recommended, as the addition of the opioid antagonist naloxone is believed to reduce the risk of abuse via injection or insufflation without causing impairment when used appropriately (sublingual administration).[90][91] Naltrexone, a μ-opioid receptor antagonist, also blocks opioids' euphoric effects by occupying the opioid receptor, but it does not activate it, so it does not produce sedation, analgesia, or euphoria, and thus has no potential for abuse or diversion.[92][93] Buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for medication-assisted treatment (MAT).[94] In the U.S., the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) certifies opioid treatment programs (OTPs), where methadone can be dispensed, and issues buprenorphine waivers to practitioners.[95][96]

Pregnant women with opioid use disorder can also receive treatment with methadone, naltrexone, or buprenorphine.[97]

The driving principle behind ORT is the patient's reclamation of a self-directed life.[98] ORT facilitates this process by reducing symptoms of drug withdrawal and drug cravings; a strong euphoric effect is not experienced as a result of the treatment drug.[89][98] In some countries (not the U.S. or Australia),[89] regulations enforce a limited time for people on ORT programs that conclude when a stable economic and psychosocial situation is achieved. (People with HIV/AIDS or hepatitis C are usually excluded from this requirement.) In practice, 40–65% of patients maintain abstinence from additional opioids while receiving opioid replacement therapy and 70–95% can reduce their use significantly.[89] Medical (improper diluents, non-sterile injecting equipment), psychosocial (mental health, relationships), and legal (arrest and imprisonment) issues that can arise from the use of illegal opioids are concurrently eliminated or reduced.[89] Clonidine or lofexidine can help treat the symptoms of withdrawal.[99]

The period when initiating methadone and the time immediately after discontinuing treatment with both drugs are periods of particularly increased mortality risk, which should be dealt with by both public health and clinical strategies.[7] ORT has proven to be the most effective treatment for improving the health and living condition of people experiencing illegal opiate use or dependence, including mortality reduction[89][100][7] and overall societal costs, such as the economic loss from drug-related crime and healthcare expenditure.[89] A review of UK hospital policies found that local guidelines delayed access to substitute opioids, for instance by requiring lab tests to demonstrate recent use or input from specialist drug teams before prescribing. Delays to access can increase people's risk of discharging themselves early against medical advice.[101][102] ORT is endorsed by the World Health Organization, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and UNAIDS as effective at reducing injection, lowering risk for HIV/AIDS, and promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy.[7]

Buprenorphine and methadone work by reducing opioid cravings, easing withdrawal symptoms, and blocking the euphoric effects of opioids via cross-tolerance,[103] and in the case of buprenorphine, a high-affinity partial opioid agonist, also due to opioid receptor saturation.[104] It is this property of buprenorphine that can induce acute withdrawal when administered before other opioids have left the body.

Methadone

Important considerations when initiating methadone include the patient's opioid tolerance, the time since last opioid use, the type of opioid used (long-acting vs. short-acting), and the risk of methadone toxicity.[105]

Methadone is a full-opioid agonist used for both opioid overuse treatment and for chronic pain.[106] It is the most commonly prescribed medication for addiction.[107] Methadone comes in a different forms: tablet, oral solution, or an injection.[106]

One of methadone's benefits is that it can last up to 56 hours in the body, so if a patient misses one of their daily doses (~24 hrs.), they will not typically struggle with withdrawal symptoms.[106] Other advantages of methadone include reduction in infectious disease related to injection drug use and reduced mortality. When patients taking MAT improve and want to refrain from taking methadone, they must be properly weaned off the medication, which must be done under medical observation. Methadone has a number of serious side effects, including slowed breathing, nausea, vomiting, restlessness, and headache.[108]

Dosages can be adjusted after 1–2 days, or another medication may be recommended for your situation if you experience side effects. Lung and breathing complications are possible long-term side effects of methadone use. Methadone, as an opiate, has the potential to be addictive. Many opponents believe that replacement drugs only substitute one addiction with another, and that methadone can be manipulated and exploited in some cases.

Buprenorphine

Important considerations when initiating buprenorphine include withdrawal symptom severity, the time since last opioid use, and the type of opioid used (long-acting vs. short-acting).[109] Initiating buprenorphine too soon can lead to rapidly-triggered withdrawal symptoms (i.e., precipitated withdrawal).[110] This is because buprenorphine has a high affinity for opioid receptors and is only a partial opioid agonist, meaning that as buprenorphine displaces full opioid agonists, a much weaker analgesic and euphoric effect is produced.[110]

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid receptor agonist. Unlike methadone and other full opioid receptor agonists, buprenorphine is less likely to cause respiratory depression due to its ceiling effect.[92] This is because buprenorphine's effects do not increase linearly past moderate doses.[111] Buprenorphine is known to be more at a risk of misuse or overdose compared to buprenorphine-naloxone and methadone, but treatment with buprenorphine may be associated with reduced mortality.[106][7] Buprenorphine under the tongue is often used to manage opioid dependence. Preparations were approved for this use in the United States in 2002.[112] A month-long injectable version of buprenorphine was approved by the FDA in 2017.[113]

Buprenorphine/Naloxone

Important considerations when initiating buprenorphine/naloxone include withdrawal symptom severity, the time since last opioid use, and the type of opioid used (long-acting vs. short-acting).[109] Though not standard practice, clinicians are exploring micro-induction protocols for buprenorphine/naloxone that prioritizes rapid induction with small, increasing doses.[114] The theoretical benefit of this form of induction is that treatment can be initiated irrespective of withdrawal symptoms.[114]

Some formulations of buprenorphine incorporate the opiate antagonist naloxone during the production of the pill form to prevent people from crushing the tablets and injecting them, instead of using the sublingual (under the tongue) route of administration.[89] Buprenorphine/naloxone formulations are available as tablets and films.[95] The combined tablet works via sublingual administration because buprenorphine maintains adequate bioavailability (35-55%) while naloxone doesn't (~10%).[115] When injected, naloxone has higher bioavailability, thereby blocking the pain and craving-reducing effects of buprenorphine.[115]

Naltrexone

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist used for the treatment of opioid addiction.[116][117] Naltrexone is not as widely used as buprenorphine or methadone for OUD due to low rates of patient acceptance, non-adherence due to daily dosing, and difficulty achieving abstinence from opioids before beginning treatment. Additionally, dosing naltrexone after recent opioid use could lead to precipitated withdrawal. Conversely, naltrexone antagonism at the opioid receptor can be overcome with higher doses of opioids.[118] Naltrexone monthly IM injections received FDA approval in 2010, for the treatment of opioid dependence in abstinent opioid users.[116][119]

Other opioids

Evidence of effects of heroin maintenance compared to methadone are unclear as of 2010.[120] A Cochrane review found some evidence in opioid users who had not improved with other treatments.[121] In Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, long-term injecting drug users who do not benefit from methadone and other medication options may be treated with injectable heroin that is administered under the supervision of medical staff.[122] Other countries where it is available include Spain, Denmark, Belgium, Canada, and Luxembourg.[123]

Dihydrocodeine in both extended-release and immediate-release form are also sometimes used for maintenance treatment as an alternative to methadone or buprenorphine in some European countries.[124] Dihydrocodeine is an opioid agonist.[125] It may be used as a second line treatment.[126] A 2020 systematic review found low quality evidence that dihydrocodeine may be no more effective than other routinely used medication interventions in reducing illicit opiate use.[127]

An extended-release morphine confers a possible reduction of opioid use and with fewer depressive symptoms but overall more adverse effects when compared to other forms of long-acting opioids. Retention in treatment was not found to be significantly different.[128] It is used in Switzerland and more recently in Canada.[129]

Behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a form of psychosocial intervention that is used to improve mental health, may not be as effective as other forms of treatment.[130] CBT primarily focuses on an individual's coping strategies to help change their cognition, behaviors and emotions about the problem. This intervention has demonstrated success in many psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression) and substance use disorders (e.g., tobacco).[131] However, the use of CBT alone in opioid dependence has declined due to the lack of efficacy, and many are relying on medication therapy or medication therapy with CBT, since both were found to be more efficacious than CBT alone. A form of CBT therapy known as motivational interviewing (MI) is often used opioid use disorder. MI leverages a person intrinsic motivation to recover through education, formulation of relapse prevention strategies, reward for adherence to treatment guidelines, and positive thinking to keep motivation high—which are based on a person's socioeconomic status, gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and their readiness to recover.[132][133][134]

Twelve-step programs

While medical treatment may help with the initial symptoms of opioid withdrawal, once the first stages of withdrawal are through, a method for long-term preventative care is attendance at 12-step groups such as Narcotics Anonymous.[135] Narcotics Anonymous is a global service that provides multilingual recovery information and public meetings free of charge.[136] Some evidence supports the use of these programs in adolescents as well.[137]

The 12-step program is an adapted form of the Alcoholics Anonymous program. The program strives to help create behavioural change by fostering peer-support and self-help programs. The model helps assert the gravity of addiction by enforcing the idea that addicts must surrender to the fact that they are addicted and be able to recognize the problem. It also helps maintain self-control and restraint to help promote one's capabilities.[138]

Epidemiology

Globally, the number of people with opioid dependence increased from 10.4 million in 1990 to 15.5 million in 2010.[7] In 2016, the numbers rose to 27 million people who experienced this disorder.[139] Opioid use disorders resulted in 122,000 deaths worldwide in 2015,[140] up from 18,000 deaths in 1990.[141] Deaths from all causes rose from 47.5 million in 1990 to 55.8 million in 2013.[141][140]

United States

The current epidemic of opioid abuse is the most lethal drug epidemic in American history.[21] In 2008, there were four times as many deaths due to overdose than there were in 1999.[143] In 2017, in the US, "the age-adjusted drug poisoning death rate involving opioid analgesics increased from 1.4 to 5.4 deaths per 100,000 population between 1999 and 2010, decreased to 5.1 in 2012 and 2013, then increased to 5.9 in 2014, and to 7.0 in 2015. The age-adjusted drug poisoning death rate involving heroin doubled from 0.7 to 1.4 deaths per 100,000 resident population between 1999 and 2011 and then continued to increase to 4.1 in 2015."[144]

In 2017, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced a public health emergency due to an increase in the misuse of opioids.[145] The administration introduced a strategic framework called the Five-Point Opioid Strategy, which includes providing access recovery services, increasing the availability of reversing agents for overdose, funding opioid misuse and pain research, changing treatments of people managing pain, and updating public health reports related to combating opioid drug misuse.[145][146]

The US epidemic in the 2000s is related to a number of factors.[16] Rates of opioid use and dependency vary by age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status.[16] With respect to race the discrepancy in deaths is thought to be due to an interplay between physician prescribing and lack of access to healthcare and certain prescription drugs.[16] Men are at higher risk for opioid use and dependency than women,[147][148] and men also account for more opioid overdoses than women, although this gap is closing.[147] Women are more likely to be prescribed pain relievers, be given higher doses, use them for longer durations, and may become dependent upon them faster.[149]

Deaths due to opioid use also tend to skew at older ages than deaths from use of other illicit drugs.[148][150][151] This does not reflect opioid use as a whole, which includes individuals in younger age demographics. Overdoses from opioids are highest among individuals who are between the ages of 40 and 50,[151] in contrast to heroin overdoses, which are highest among individuals who are between the ages of 20 and 30.[150] 21- to 35-year-olds represent 77% of individuals who enter treatment for opioid use disorder,[152] however, the average age of first-time use of prescription painkillers was 21.2 years of age in 2013.[153] Among the middle class means of acquiring funds have included Elder financial abuse through a vulnerability of financial transactions of selling items and international dealers noticing a lack of enforcement in their transaction scams throughout the Caribbean.[154]

Since 2018, with the US federal government's passing of the SUPPORT (Substance Use-Disorder Prevention That Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act) Act, federal restrictions on methadone use for patients receiving Medicare have been lifted.[155] Since March 2020, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, buprenorphine may be dispensed via telemedicine in the U.S.[156][157]

In October 2021, New York Governor Kathy Hochul signed legislation to combat the opioid crisis. This included establishing a program for the use of medication-assisted substance use disorder treatment for incarcerated individuals in state and local correctional facilities, decriminalizing the possession and sale of hypodermic needles and syringes, establishing an online directory for distributors of opioid antagonists, and expanding the number of eligible crimes committed by individuals with a substance use disorder that may be considered for diversion to a substance use treatment program.[158] Until these laws were signed, incarcerated New Yorkers did not reliably have access to medication-assisted treatment and syringe possession was still a class A misdemeanor despite New York authorizing and funding syringe exchange and access programs.[159] This legislation acknowledges the ways New York State laws have contributed to opioid deaths: in 2020 more than 5112 people died from overdoses in New York State, with 2192 deaths in New York City.[160]

- Charts of deaths involving specific opioids and classes of opioids - US National Institute on Drug Abuse

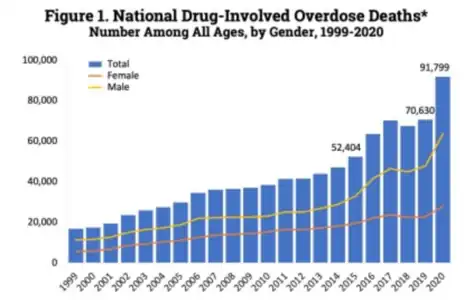

US yearly deaths from all opioid drugs. Included in this number are opioid analgesics, along with heroin and illicit synthetic opioids.[161]

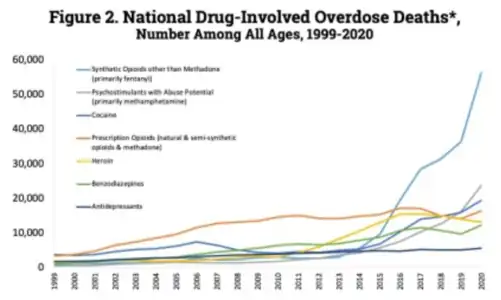

US yearly deaths from all opioid drugs. Included in this number are opioid analgesics, along with heroin and illicit synthetic opioids.[161] US yearly deaths by drug category.[161]

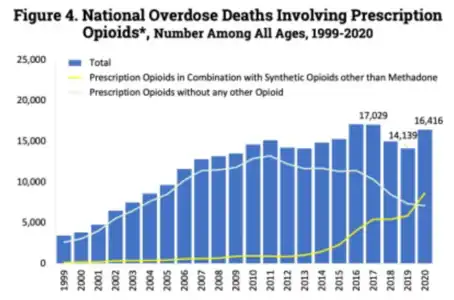

US yearly deaths by drug category.[161] US yearly opioid overdose deaths involving prescription opioids. Non-methadone synthetics is a category dominated by illegally acquired fentanyl, and has been excluded.[162]

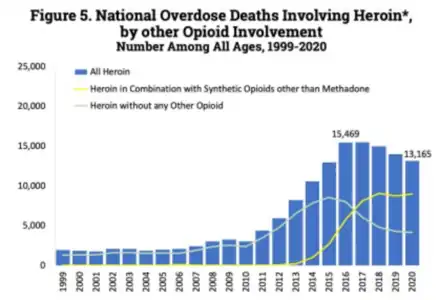

US yearly opioid overdose deaths involving prescription opioids. Non-methadone synthetics is a category dominated by illegally acquired fentanyl, and has been excluded.[162] US yearly opioid overdose deaths involving heroin.[162]

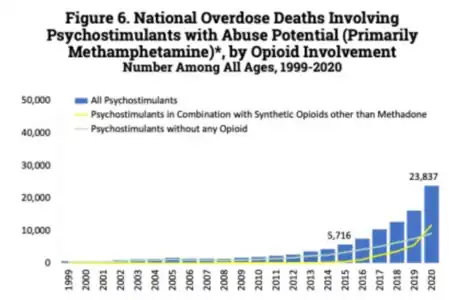

US yearly opioid overdose deaths involving heroin.[162] US yearly opioid overdose deaths involving psychostimulants (primarily methamphetamine).[162]

US yearly opioid overdose deaths involving psychostimulants (primarily methamphetamine).[162]

History

Opiate misuse has been recorded at least since 300 BC. Greek mythology describes Nepenthe (Greek “free from sorrow”) and how it was used by the hero of the Odyssey. Opioids have been used in the Near East for centuries. The purification of and isolation of opiates occurred in the early 19th century.[29]

Levacetylmethadol was previously used to treat opioid dependence. In 2003 the drug's manufacturer discontinued production. There are no available generic versions. LAAM produced long-lasting effects, which allowed the person receiving treatment to visit a clinic only three times per week, as opposed to daily as with methadone.[163] In 2001, levacetylmethadol was removed from the European market due to reports of life-threatening ventricular rhythm disorders.[164] In 2003, Roxane Laboratories, Inc. discontinued Orlaam in the US.[165]

See also

- Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- Doctor shopping

- Hyperkatifeia, hypersensitivity to emotional distress in the context of opioid abuse

- Prescription drug abuse

References

- "FDA approves first buprenorphine implant for treatment of opioid dependence". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 26 May 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- "3 Patient Assessment". Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). 2004.

- "Commonly Used Terms". www.cdc.gov. 29 August 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.), Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, pp. 540–546, ISBN 978-0890425558

- Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration (30 September 2014). "Substance Use Disorders".

- "Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy". ACOG. August 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, Ferri M, Pastor-Barriuso R (April 2017). "Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies". BMJ. 357: j1550. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1550. PMC 5421454. PMID 28446428.

- "Treatment for Substance Use Disorders". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. October 2014.

- McDonald R, Strang J (July 2016). "Are take-home naloxone programmes effective? Systematic review utilizing application of the Bradford Hill criteria". Addiction. 111 (7): 1177–87. doi:10.1111/add.13326. PMC 5071734. PMID 27028542.

- Sharma B, Bruner A, Barnett G, Fishman M (July 2016). "Opioid Use Disorders". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 25 (3): 473–87. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2016.03.002. PMC 4920977. PMID 27338968.

- Dydyk, Alexander M.; Jain, Nitesh K.; Gupta, Mohit (2022), "Opioid Use Disorder", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31985959, retrieved 16 November 2022

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. Internet Archive. Arlington, VA : American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Shah, Mansi; Huecker, Martin R. (2022), "Opioid Withdrawal", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30252268, retrieved 16 November 2022

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". The New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–71. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder.

- Webster, Lynn R. (November 2017). "Risk Factors for Opioid-Use Disorder and Overdose". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 125 (5): 1741–1748. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002496. ISSN 1526-7598. PMID 29049118. S2CID 19635834.

- Santoro, T. N.; Santoro, J. D. (2018). "Racial Bias in the US Opioid Epidemic: A Review of the History of Systemic Bias and Implications for Care". Cureus. 10 (12): e3733. doi:10.7759/cureus.3733. PMC 6384031. PMID 30800543.

- Dowell, Deborah (2022). "CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain — United States, 2022". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 71 (3): 1–95. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1. ISSN 1057-5987. PMC 9639433. PMID 36327391.

- "A Prescriber's Guide to Medicare Prescription Drug (Part D) Opioid Policies" (PDF).

- Mohamadi A, Chan JJ, Lian J, Wright CL, Marin AM, Rodriguez EK, von Keudell A, Nazarian A (August 2018). "Risk Factors and Pooled Rate of Prolonged Opioid Use Following Trauma or Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-(Regression) Analysis". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 100 (15): 1332–1340. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.01239. PMID 30063596. S2CID 51891341.

- "Prescription opioid use is a risk factor for heroin use". National Institute on Drug Abuse. October 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Hughes, Evan (2 May 2018). "The Pain Hustlers". New York Times. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "Trends in the Use of Methadone, Buprenorphine, and Extended-release Naltrexone at Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities: 2003-2015 (Update)". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Donovan, Dennis M.; Ingalsbe, Michelle H.; Benbow, James; Daley, Dennis C. (2013). "12-Step Interventions and Mutual Support Programs for Substance Use Disorders: An Overview". Social Work in Public Health. 28 (3–4): 313–332. doi:10.1080/19371918.2013.774663. ISSN 1937-1918. PMC 3753023. PMID 23731422.

- "Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons — United States, 2014". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- CDC (30 August 2022). "Disease of the Week - Opioid Use Disorder". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- "Data Brief 294. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2016" (PDF). CDC. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Treatment, Center for Substance Abuse (2006). "[Table], Figure 4-4: Signs and Symptoms of Opioid Intoxication and Withdrawal". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- Fentanyl. Image 4 of 17. US DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration). See archive with caption: "photo illustration of 2 milligrams of fentanyl, a lethal dose in most people".

- Kosten TR, Haile CN. Opioid-Related Disorders. In: Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, Loscalzo J. eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 19e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2014. http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=1130§ionid=79757372 Accessed 9 March 2017.

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 547–549. ISBN 9780890425541.

- Shah, Mansi; Huecker, Martin R. (2019), "Opioid Withdrawal", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30252268, retrieved 21 October 2019

- Ries RK, Miller SC, Fiellin DA (2009). Principles of Addiction Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 593–594. ISBN 9780781774772.

- Rahimi-Movaghar A, Gholami J, Amato L, Hoseinie L, Yousefi-Nooraie R, Amin-Esmaeili M (June 2018). "Pharmacological therapies for management of opium withdrawal". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (6): CD007522. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007522.pub2. PMC 6513031. PMID 29929212.

- Chen KW, Banducci AN, Guller L, Macatee RJ, Lavelle A, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW (November 2011). "An examination of psychiatric comorbidities as a function of gender and substance type within an inpatient substance use treatment program". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 118 (2–3): 92–9. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.003. PMC 3188332. PMID 21514751.

- Webster LR, Webster RM (2005). "Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool". Pain Medicine. 6 (6): 432–42. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00072.x. PMID 16336480.

- Papaleontiou M, Henderson CR, Turner BJ, Moore AA, Olkhovskaya Y, Amanfo L, Reid MC. Outcomes associated with opioid use in thetreatment of chronic noncancer pain in older adults: a systematic reviewand meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1353–69.

- Noble M, Tregear SJ, Treadwell JR, Schoelles K. Long-term opioidtherapy for chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety. J Pain Symptom Manag 2008;35:214–28.

- Martell BA, O’Connor PG, Kerns RD, Becker WC, Morales KH, KostenTR, Fiellin DA. Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain:prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann Intern Med2007;146:116–27

- Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. PAIN 2004;112:372–80

- Goesling, Jenna; DeJonckheere, Melissa; Pierce, Jennifer; Williams, David A.; Brummett, Chad M.; Hassett, Afton L.; Clauw, Daniel J. (16 January 2019). "Opioid cessation and chronic pain: perspectives of former opioid users". Pain. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health). 160 (5): 1131–1145. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001493. ISSN 0304-3959. PMC 8442035. PMID 30889052.

- Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, Jensen AC, DeRonne B, Goldsmith ES, Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Noorbaloochi S. Effect of opioid vs nonopioidmedications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain orhip or knee osteoarthritis pain: the SPACE randomized clinical trial. JAMA2018;319:872–82.

- Eriksen J, Sjogren P, Bruera E, Ekholm O, Rasmussen NK. Critical issueson opioids in chronic non-cancer pain: an epidemiological study. PAIN2006;125:172–9.

- Chaparro LE, Furlan AD, Deshpande A, Mailis-Gagnon A, Atlas S, TurkDC. Opioids compared with placebo or other treatments for chronic lowback pain: an update of the Cochrane Review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)2014;39:556–63.

- Substitution maintenance therapy in the management of opioid dependence and HIV/AIDS prevention (PDF). World Health Organization. 2004. ISBN 978-92-4-159115-7.

- "Treatment of opioid dependence". WHO. 2004. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- Longo, Dan L.; Volkow, Nora D.; Koob, George F.; McLellan, A. Thomas (28 January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

- Hyman, SE (January 2007). "The neurobiology of addiction: implications for voluntary control of behavior". The American Journal of Bioethics. 7 (1): 8–11. doi:10.1080/15265160601063969. PMID 17366151. S2CID 347138.

- Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–43. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/enestler. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process.

- Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–375. ISBN 9780071481274.

- "Glossary of Terms". Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Department of Neuroscience. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (October 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 12 (11): 623–37. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

- Olsen CM (December 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704. PMID 21459101.

- Ruffle JK (November 2014). "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 40 (6): 428–37. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822. S2CID 19157711.

- Blum K, Werner T, Carnes S, Carnes P, Bowirrat A, Giordano J, Oscar-Berman M, Gold M (2012). "Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll: hypothesizing common mesolimbic activation as a function of reward gene polymorphisms". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 44 (1): 38–55. doi:10.1080/02791072.2012.662112. PMC 4040958. PMID 22641964.

- Bourdy R, Barrot M (November 2012). "A new control center for dopaminergic systems: pulling the VTA by the tail". Trends in Neurosciences. 35 (11): 681–90. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2012.06.007. PMID 22824232. S2CID 43434322.

- "Morphine addiction – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG. Kanehisa Laboratories. 18 June 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Mistry C, Bawor M, Desai D, Marsh D, Samaan Z (May 2014). "Genetics of Opioid Dependence: A Review of the Genetic Contribution to Opioid Dependence". Current Psychiatry Reviews. 10 (2): 156–167. doi:10.2174/1573400510666140320000928. PMC 4155832. PMID 25242908.

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND (October 2011). "Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 12 (11): 652–69. doi:10.1038/nrn3119. PMC 3462342. PMID 22011681.

- Schoenbum, Geoffrey; Shaham, Yavin (February 2008). "The role of orbitofrontal cortex in drug addiction: a review of preclinical studies". Biol Psychiatry. 63 (3): 256–262. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.003. PMC 2246020. PMID 17719014.

- Ieong HF, Yuan Z (1 January 2017). "Resting-State Neuroimaging and Neuropsychological Findings in Opioid Use Disorder during Abstinence: A Review". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 11: 169. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2017.00169. PMC 5382168. PMID 28428748.

- Nestler EJ (August 2016). "Reflections on: "A general role for adaptations in G-Proteins and the cyclic AMP system in mediating the chronic actions of morphine and cocaine on neuronal function"". Brain Research. 1645: 71–4. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2015.12.039. PMC 4927417. PMID 26740398.

Specifically, opiates in several CNS regions including NAc, and cocaine more selectively in NAc induce expression of certain adenylyl cyclase isoforms and PKA subunits via the transcription factor, CREB, and these transcriptional adaptations serve a homeostatic function to oppose drug action. In certain brain regions, such as locus coeruleus, these adaptations mediate aspects of physical opiate dependence and withdrawal, whereas in NAc they mediate reward tolerance and dependence that drives increased drug self-administration.

- "Opioid Use Disorder: Diagnostic Criteria". Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (PDF). American Psychiatric Association. pp. 1–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Vargas-Perez H, Ting-A Kee R, Walton CH, Hansen DM, Razavi R, Clarke L, Bufalino MR, Allison DW, Steffensen SC, van der Kooy D (June 2009). "Ventral tegmental area BDNF induces an opiate-dependent-like reward state in naive rats". Science. 324 (5935): 1732–4. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1732V. doi:10.1126/science.1168501. PMC 2913611. PMID 19478142.

- Laviolette SR, van der Kooy D (March 2001). "GABA(A) receptors in the ventral tegmental area control bidirectional reward signalling between dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neural motivational systems". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 13 (5): 1009–15. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01458.x. PMID 11264674. S2CID 46694281.

- Nutt, David; King, Leslie A.; Saulsbury, William; Blakemore, Colin (24 March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- Hall FS, Drgonova J, Jain S, Uhl GR (December 2013). "Implications of genome wide association studies for addiction: are our a priori assumptions all wrong?". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 140 (3): 267–79. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.07.006. PMC 3797854. PMID 23872493.

- Bruehl S, Apkarian AV, Ballantyne JC, Berger A, Borsook D, Chen WG, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Horn SD, Iadarola MJ, Inturrisi CE, Lao L, Mackey S, Mao J, Sawczuk A, Uhl GR, Witter J, Woolf CJ, Zubieta JK, Lin Y (February 2013). "Personalized medicine and opioid analgesic prescribing for chronic pain: opportunities and challenges". The Journal of Pain. 14 (2): 103–13. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2012.10.016. PMC 3564046. PMID 23374939.

- Khokhar JY, Ferguson CS, Zhu AZ, Tyndale RF (2010). "Pharmacogenetics of drug dependence: role of gene variations in susceptibility and treatment". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 50: 39–61. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105826. PMID 20055697. S2CID 2158248.

- "CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center". www.cdc.gov. 31 August 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- "Our Commitment to Fight Opioid Abuse | CVS Health". CVS Health. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- "Combat opioid abuse | Walgreens". Walgreens. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- "Naloxone for Treatment of Opioid Overdose" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- "Prevent Opioid Use Disorder | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center". www.cdc.gov. 31 August 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Naloxone. 23 October 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons — United States, 2014". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Childs R (July 2015). "Law enforcement and naloxone utilization in the United States" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. pp. 1–24. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- "Case studies: Standing orders". NaloxoneInfo.org. Open Society Foundations. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Schuckit MA (July 2016). "Treatment of Opioid-Use Disorders". The New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (4): 357–68. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1604339. PMID 27464203.

- Christie C, Baker C, Cooper R, Kennedy CP, Madras B, Bondi FA. The president’s commission on combating drug addiction and the opioid crisis. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, November 2017;1.

- "Naloxone Opioid Overdose Reversal Medication". CVS Health. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- Morin, Kristen A; Vojtesek, Frank; Acharya, Shreedhar; Dabous, John R; Marsh, David C (26 October 2021). "Evidence of Increased Age and Sex Standardized Death Rates Among Individuals Who Accessed Opioid Agonist Treatment Before the Era of Synthetic Opioids in Ontario, Canada". Cureus. Cureus, Inc. 13 (10): e19051. doi:10.7759/cureus.19051. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 8608679. PMID 34853762.

- Hser, Yih-Ing; Hoffman, Valerie; Grella, Christine E.; Anglin, M. Douglas (1 May 2001). "A 33-Year Follow-up of Narcotics Addicts". Archives of General Psychiatry. American Medical Association (AMA). 58 (5): 503–8. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503. ISSN 0003-990X. PMID 11343531.

- Horon, Isabelle L.; Singal, Pooja; Fowler, David R.; Sharfstein, Joshua M. (2018). "Standard Death Certificates Versus Enhanced Surveillance to Identify Heroin Overdose–Related Deaths". American Journal of Public Health. American Public Health Association. 108 (6): 777–781. doi:10.2105/ajph.2018.304385. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 5944879. PMID 29672148.

- Dowell, Deborah (2022). "CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain — United States, 2022". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 71 (3): 1–95. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1. ISSN 1057-5987. PMC 9639433. PMID 36327391.

- Research, Center for Drug Evaluation and (2 March 2021). "Abuse-Deterrent Opioid Analgesics". FDA.

- Nicholls L, Bragaw L, Ruetsch C (February 2010). "Opioid dependence treatment and guidelines". Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 16 (1 Suppl B): S14–21. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.S1-B.14. PMC 10437806. PMID 20146550.

- Nielsen, Suzanne; Tse, Wai Chung; Larance, Briony (5 September 2022). Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group (ed.). "Opioid agonist treatment for people who are dependent on pharmaceutical opioids". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (9): CD011117. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011117.pub3. PMC 9443668. PMID 36063082.

- "Opioid substitution therapy or treatment (OST)". Migration and Home Affairs. European Commission. 14 March 2017.

- Richard P. Mattick et al.: National Evaluation of Pharmacotherapies for Opioid Dependence (NEPOD): Report of Results and Recommendation

- Rees, John; Garcia, Gabriel (2019). "Clinic Payment Options as a Barrier to Accessing Medication-assisted Treatment for Opioid Use in Albuquerque, New Mexico". Addictive Disorders & Their Treatment. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health). 18 (4): 246–248. doi:10.1097/adt.0000000000000175. ISSN 1531-5754. S2CID 146020892.

- Bruneau J, Ahamad K, Goyer MÈ, Poulin G, Selby P, Fischer B, Wild TC, Wood E (March 2018). "Management of opioid use disorders: a national clinical practice guideline". CMAJ. 190 (9): E247–E257. doi:10.1503/cmaj.170958. PMC 5837873. PMID 29507156.

- "Medications for Opioid Use Disorder - Treatment Improvement Protocol 63". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Gastfriend DR (January 2011). "Intramuscular extended-release naltrexone: current evidence". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1216 (1): 144–66. Bibcode:2011NYASA1216..144G. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05900.x. PMID 21272018. S2CID 45133931.

- "MAT Medications, Counseling, and Related Conditions". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- "Buprenorphine". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- "Methadone". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- Tran, Tran H.; Griffin, Brooke L.; Stone, Rebecca H.; Vest, Kathleen M.; Todd, Timothy J. (2017). "Methadone, Buprenorphine, and Naltrexone for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnant Women". Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmaoclogy and Drug Therapy. Wiley. 37 (7): 824–839. doi:10.1002/phar.1958. ISSN 0277-0008. PMID 28543191. S2CID 13772333.

- "Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- Gowing L, Farrell M, Ali R, White JM (May 2016). "Alpha₂-adrenergic agonists for the management of opioid withdrawal". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (5): CD002024. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002024.pub5. PMC 7081129. PMID 27140827.

- Michel et al.: Substitution treatment for opioid addicts in Germany, Harm Reduct J. 2007; 4: 5.

- "Many hospital policies create barriers to good management of opioid withdrawal". NIHR Evidence. 16 November 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_54639. S2CID 253608569.

- Harris, Magdalena; Holland, Adam; Lewer, Dan; Brown, Michael; Eastwood, Niamh; Sutton, Gary; Sansom, Ben; Cruickshank, Gabby; Bradbury, Molly; Guest, Isabelle; Scott, Jenny (14 April 2022). "Barriers to management of opioid withdrawal in hospitals in England: a document analysis of hospital policies on the management of substance dependence". BMC Medicine. 20 (1): 151. doi:10.1186/s12916-022-02351-y. ISSN 1741-7015. PMC 9007696. PMID 35418095.

- Bonhomme J, Shim RS, Gooden R, Tyus D, Rust G (July 2012). "Opioid addiction and abuse in primary care practice: a comparison of methadone and buprenorphine as treatment options". Journal of the National Medical Association. 104 (7–8): 342–50. doi:10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30175-9. PMC 4039205. PMID 23092049.

- Orman JS, Keating GM (2009). "Buprenorphine/naloxone: a review of its use in the treatment of opioid dependence". Drugs. 69 (5): 577–607. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969050-00006. PMID 19368419. S2CID 209147406.

- "West Virginia Department of Human Health & Resources_Burea for Medical Services_Methadone" (PDF).

- Koehl, Jennifer L; Zimmerman, David E; Bridgeman, Patrick J (18 July 2019). "Medications for management of opioid use disorder". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 76 (15): 1097–1103. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxz105. ISSN 1079-2082. PMID 31361869.

- "Trends in the Use of Methadone, Buprenorphine, and Extended-release Naltrexone at Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities: 2003-2015 (Update)". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- "Methadone Side Effects: Common, Severe, Long Term". Drugs.com. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- "SAMHSA Buprenorphine Quick Start Guide" (PDF).

- Rosado, James; Walsh, Sharon L.; Bigelow, George E.; Strain, Eric C. (8 October 2007). "Sublingual Buprenorphine/Naloxone Precipitated Withdrawal in Subjects Maintained on 100 mg of Daily Methadone". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 90 (2–3): 261–269. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.006. ISSN 0376-8716. PMC 2094723. PMID 17517480.

- "What is Buprenorphine? | UAMS Psychiatric Research Institute". psychiatry.uams.edu/. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- "Subutex and Suboxone Approved to Treat Opiate Dependence". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 8 October 2002. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- "Sublocade (buprenorphine) FDA Approval History". Drugs.com. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- Wong, James S. H.; Nikoo, Mohammadali; Westenberg, Jean N.; Suen, Janet G.; Wong, Jennifer Y. C.; Krausz, Reinhard M.; Schütz, Christian G.; Vogel, Marc; Sidhu, Jesse A.; Moe, Jessica; Arishenkoff, Shane; Griesdale, Donald; Mathew, Nickie; Azar, Pouya (12 February 2021). "Comparing rapid micro-induction and standard induction of buprenorphine/naloxone for treatment of opioid use disorder: protocol for an open-label, parallel-group, superiority, randomized controlled trial". Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 16 (1): 11. doi:10.1186/s13722-021-00220-2. ISSN 1940-0640. PMC 7881636. PMID 33579359.

- Yokell, Michael A.; Zaller, Nickolas D.; Green, Traci C.; Rich, Josiah D. (1 March 2011). "Buprenorphine and Buprenorphine/Naloxone Diversion, Misuse, and Illicit Use: An International Review". Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 4 (1): 28–41. doi:10.2174/1874473711104010028. ISSN 1874-4737. PMC 3154701. PMID 21466501.

- "Vivitrol Prescribing Information" (PDF). Alkermes Inc. July 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Skolnick P (January 2018). "The Opioid Epidemic: Crisis and Solutions". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 58 (1): 143–159. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010617-052534. PMID 28968188.

- Sullivan MA, Garawi F, Bisaga A, Comer SD, Carpenter K, Raby WN, Anen SJ, Brooks AC, Jiang H, Akerele E, Nunes EV (December 2007). "Management of relapse in naltrexone maintenance for heroin dependence". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 91 (2–3): 289–92. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.013. PMC 4153601. PMID 17681716.

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (2009). Chapter 4—Oral Naltrexone. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US).

- Dalsbø, TK; Steiro, AK; Hammerstrøm, KT; Smedslund, G (2010). Heroin Maintenance for Persons with Chronic Heroin Dependence (Report). Oslo, Norway: Knowledge Centre for the Health Services at The Norwegian Institute of Public Health. PMID 29320074.

- Ferri M, Davoli M, Perucci CA (December 2011). "Heroin maintenance for chronic heroin-dependent individuals". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (12): CD003410. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003410.pub4. PMC 7017638. PMID 22161378. S2CID 6772720.

- Rehm J, Gschwend P, Steffen T, Gutzwiller F, Dobler-Mikola A, Uchtenhagen A (October 2001). "Feasibility, safety, and efficacy of injectable heroin prescription for refractory opioid addicts: a follow-up study". Lancet. 358 (9291): 1417–23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06529-1. PMID 11705488. S2CID 24542893.

- "Heroin Assisted Treatment | Drug Policy Alliance". Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Robertson JR, Raab GM, Bruce M, McKenzie JS, Storkey HR, Salter A (December 2006). "Addressing the efficacy of dihydrocodeine versus methadone as an alternative maintenance treatment for opiate dependence: A randomized controlled trial". Addiction. 101 (12): 1752–9. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01603.x. PMID 17156174.

- "Dihydrocodeine". Pubchem.

- "Login". online.lexi.com. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Carney, Tara; Van Hout, Marie Claire; Norman, Ian; Dada, Siphokazi; Siegfried, Nandi; Parry, Charles Dh (18 February 2020). "Dihydrocodeine for detoxification and maintenance treatment in individuals with opiate use disorders". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD012254. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012254.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7027221. PMID 32068247.

- Ferri M, Minozzi S, Bo A, Amato L (June 2013). "Slow-release oral morphine as maintenance therapy for opioid dependence". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD009879. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009879.pub2. PMID 23740540.

- "Bundesamt für Gesundheit – Substitutionsgestützte Behandlung mit Diacetylmorphin (Heroin)". Archived from the original on 13 March 2016.

- Beck JS (18 August 2011). Cognitive behavior therapy : basics and beyond (Second ed.). New York. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9781609185046. OCLC 698332858.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Huibers MJ, Beurskens AJ, Bleijenberg G, van Schayck CP (July 2007). "Psychosocial interventions by general practitioners". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (3): CD003494. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003494.pub2. hdl:2066/52984. PMC 7003673. PMID 17636726.

- Longo, Dan L.; Schuckit, Marc A. (28 July 2016). "Treatment of Opioid-Use Disorders". New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (4): 357–368. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1604339. PMID 27464203.

- Vasilaki, Eirini I.; Hosier, Steven G.; Cox, W. Miles (May 2006). "The Efficacy of Motivational Interviewing as a Brief Intervention for Excessive Drinking: A Meta-Analytic Review". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 41 (3): 328–335. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agl016. PMID 16547122.

- "Psychosocial interventions for opioid use disorder". UpToDate. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- Melemis SM (September 2015). "Relapse Prevention and the Five Rules of Recovery". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 88 (3): 325–32. PMC 4553654. PMID 26339217.

- "NA". www.na.org. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Sussman S (March 2010). "A review of Alcoholics Anonymous/ Narcotics Anonymous programs for teens". Evaluation & the Health Professions. 33 (1): 26–55. doi:10.1177/0163278709356186. PMC 4181564. PMID 20164105.

- "12 Step Programs for Drug Rehab & Alcohol Treatment". American Addiction Centers. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- "WHO | Information sheet on opioid overdose". WHO. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- GBD 2015 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- Opioid Data Analysis and Resources. Drug Overdose. CDC Injury Center. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Click on "Rising Rates" tab for a graph. See data table below the graph.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. "Opioid Addiction 2016 Facts and Figures" (PDF).

- Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-term Trends in Health (PDF). Hyattsville, MD.: CDC, National Center for Health Statistics. 2017. p. 4.

- Digital Communications Division (8 May 2018). "5-Point Strategy To Combat the Opioid Crisis". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- "Strategy to Combat Opioid, Abuse, Misuse, and Overdose" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- "Prescription Opioid Overdose Data". Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Paulozzi L (12 April 2012). "Populations at risk for opioid overdose" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "Opioid Addiction: 2016 Facts and Figures" (PDF). American Society of Addiction Medicine. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "How Bad is the Opioid Epidemic?". PBS. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Han B, Polydorou S, Ferris R, Blaum CS, Ross S, McNeely J (10 November 2015). "Demographic Trends of Adults in New York City Opioid Treatment Programs--An Aging Population". Substance Use & Misuse. 50 (13): 1660–7. doi:10.3109/10826084.2015.1027929. PMID 26584180. S2CID 5520930.

- "Facts & Faces of Opioid Addiction: New Insights". MAP Health Management. 2015. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "Opioids". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 23 February 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- DeVencentis P (24 July 2017). "Grandson sold refrigerator for drugs, grandma says". USA Today.

- Peterman, Nicholas J; Palsgaard, Peggy; Vashi, Aksal; Vashi, Tejal; Kaptur, Bradley D; Yeo, Eunhae; Mccauley, Warren (2022). "Demographic and Geospatial Analysis of Buprenorphine and Methadone Prescription Rates". Cureus. 14 (5): e25477. doi:10.7759/cureus.25477. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 9246456. PMID 35800815.

- "Use of Telemedicine While Providing Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT)" (PDF). SAMHSA. 15 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Nunes, EV; Levin, FR; Reilly, MP; El-Bassel, N (March 2021). "Medication treatment for opioid use disorder in the age of COVID-19: Can new regulations modify the opioid cascade?". Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 122: 108196. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108196. PMC 7666540. PMID 33221125.

- "Hochul signs legislation package to combat opioid crisis".

- "NY Decriminalizes Syringe Possession as Part of Overdose Prevention Efforts". 7 October 2021.

- "Products - Vital Statistics Rapid Release - Provisional Drug Overdose Data". 4 November 2021.

- Abuse, National Institute on Drug (20 January 2022). "Overdose Death Rates". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 10 November 2022.

- Overdose Death Rates. By National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

- James W. Kalat, Biological Psychology. Cengage Learning. Page 81.

- EMEA 19 April 2001 EMEA Public Statement on the Recommendation to Suspend the Marketing Authorisation for Orlaam (Levacetylmethadol) in the European Union

- US FDA Safety Alerts: Orlaam (levomethadyl acetate hydrochloride) Page Last Updated: 20 August 2013 Archived 18 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Brown TK, Alper K (2018). "Treatment of opioid use disorder with ibogaine: detoxification and drug use outcomes". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 44 (1): 24–36. doi:10.1080/00952990.2017.1320802. PMID 28541119. S2CID 4401865.

- Neighbors CJ, Choi S, Healy S, Yerneni R, Sun T, Shapoval L (June 2019). "Age related medication for addiction treatment (MAT) use for opioid use disorder among Medicaid-insured patients in New York". Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 14 (1): 28. doi:10.1186/s13011-019-0215-4. PMC 6593566. PMID 31238952.

- Seabra, P., Sequeira, A., Filipe, F., Amaral, P., Simões, A., & Sequeira, R. (2022). Substance addiction consequences: outpatients severity indicators in a medication-based program. International Journal of Mental Health & Addiction, 20(3), 1837–1853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00485-3

External links

- Heroin information from the National Institute on Drug Abuse

- Opioid Dependence Treatment and Guidelines