Swedes

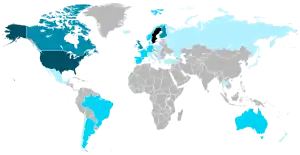

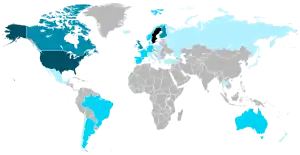

Swedes (Swedish: svenskar) are an ethnic group native to the Nordic region, primarily their nation state of Sweden, who share a common ancestry, culture, history and language. They mostly inhabit Sweden and the other Nordic countries, in particular Finland where they are an officially recognized minority,[d] with a substantial diaspora in other countries, especially the United States.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 13 million[a] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Other significant population centers:

Swedish minorities with a longer history | |

| c. 290,000 (2008)[d][2][3] | |

| 811 (2021)[4] | |

| c. 200 (2022)[5] | |

| Swedish citizens abroad | c. 546,000[c][3] |

| Swedish diaspora | c. 4.5–5 million |

| 4,347,703 (2013; ancestry)[6] 29,000 (Swedish citizens)[6] | |

| 341,845 (2011; ancestry[7] 26,000 (sole ancestry)[7] | |

| 100,000[8] | |

| 36,887[9]–90,000[10] | |

| 30,375 (2006; ancestry)[11] | |

| 30,000[12] | |

| 23,000[13] | |

| 23,000 (ancestry)[14] | |

| 20,385[15] | |

| 16,620[16] | |

| 15,000[17] | |

| 8,000[18][19] | |

| 7,400[20] | |

| 6,800[20] | |

| 4,600[20] | |

| 4,000[20] | |

| 3,233[21] | |

| 2,560[22] | |

| 2,500[20] | |

| 2,300[20] | |

| 2,000[20] | |

| 1,800[20] | |

| 1,600[20] | |

| 1,911 (2018; ancestry)[23] | |

| Languages | |

| Swedish | |

| Religion | |

| Primarily Lutheran Christianity (Church of Sweden)[24] For further details, see Religion in Sweden | |

^a The total figure is merely an estimation; sum of all the referenced populations who claim Swedish ancestry worldwide and as such might be misleading or exaggerated. ^b Since there are no official statistics regarding ethnicity in Sweden, the number does not include ethnic Swedes who were born abroad but now repatriated to Sweden, nor does it include Swedish-speaking Finns in Sweden; est. for year 2015. ^c This figure overlaps with those listed under diaspora as most Swedish citizens have emigrated to those countries listed lower in the infobox. ^d

The Swedish-speaking Finns or Finland-Swedes form a minority group in Finland. The characteristic of this minority is debated: while some see it as an ethnic group of its own[25] some view it purely as a linguistic minority.[26] The group includes about 265,000 people, comprising 5.10% of the population of mainland Finland, or 5.50%[27] if the 26,000 inhabitants of Åland are included (there are also about 60,000 Swedish-speaking Finns currently resident in Sweden). It has been presented that the ethnic group can also be perceived as a distinct Swedish-speaking nationality in Finland.[28] There are also 9,000 Swedish citizens living in Finland.[29]

| |

Etymology

The English term "Swede" has been attested in English since the late 16th century and is of Middle Dutch or Middle Low German origin.[30] In Swedish, the term is svensk, which is from the name of svear (or Swedes), the people who inhabited Svealand in eastern central Sweden,[31][32] and were listed as Suiones in Tacitus' history Germania from the first century AD. The term is believed to have been derived from the Proto-Indo-European reflexive pronominal root, *s(w)e, as the Latin suus. The word must have meant "one's own (tribesmen)". The same root and original meaning is found in the ethnonym of the Germanic tribe Suebi, preserved to this day in the name Swabia.[33][34][35]

History

Origins

Like other Scandinavians, Swedes descend from the presumably Indo-European Battle Axe culture and also the Pitted Ware culture.[36] Prior to the first century AD there is no written evidence and historiography is based solely on various forms of archeology. The Proto-Germanic language is thought to have originated in the arrival of the Battle Axe culture in Scandinavia[37] and the Germanic tribal societies of Scandinavia were thereafter surprisingly stable for thousands of years.[38] The merger of the Battle Axe and Pitted Ware cultures eventually gave rise to the Nordic Bronze Age which was followed by the Pre-Roman Iron Age. Like other North Germanic peoples, Swedes likely emerged as a distinct ethnic group during this time.[39]

Swedes enters written proto-history with the Germania of Tacitus in 98 AD. In Germania 44, 45 he mentions the Swedes (Suiones) as a powerful tribe (distinguished not merely for their arms and men, but for their powerful fleets) with ships that had a prow in both ends (longships). Which kings (kuningaz) ruled these Suiones is unknown, but Norse mythology presents a long line of legendary and semi-legendary kings going back to the last centuries BC. As for literacy in Sweden itself, the runic script was in use among the south Scandinavian elite by at least the second century AD, but all that has survived from the Roman Period is curt inscriptions on artefacts, mainly of male names, demonstrating that the people of south Scandinavia spoke Proto-Norse at the time, a language ancestral to Swedish and other North Germanic languages.

Migration Age and Vendel Period

The migration age in Sweden is marked by the extreme weather events of 535–536 which is believed to have shaken Scandinavian society to its core. As much as 50% of the population of Scandinavia is thought to have died as a result and the emerging Vendel Period shows an increased militarization of society.[40][41] Several areas with rich burial gifts have been found, including well-preserved boat inhumation graves at Vendel and Valsgärde, and tumuli at Gamla Uppsala. These were used for several generations. Some of the riches were probably acquired through the control of mining districts and the production of iron. The rulers had troops of mounted elite warriors with costly armour. Graves of mounted warriors have been found with stirrups and saddle ornaments of birds of prey in gilded bronze with encrusted garnets. The Sutton Hoo helmet very similar to helmets in Gamla Uppsala, Vendel and Valsgärde shows that the Anglo-Saxon elite had extensive contacts with Swedish elite.[42]

In the sixth century Jordanes named two tribes, which he calls the Suehans and the Suetidi, who lived in Scandza. The Suehans, he says, have very fine horses just as the Thyringi tribe (alia vero gens ibi moratur Suehans, quae velud Thyringi equis utuntur eximiis). The Icelander Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241) wrote of the sixth-century Swedish king Adils (Eadgils) that he had the finest horses of his days. The Suehans supplied black fox-skins for the Roman market. Then Jordanes names the Suetidi which is considered to be the Latin form of Svitjod. He writes that the Suetidi are the tallest of men—together with the Dani, who were of the same stock. Later he mentions other Scandinavian tribes as being of the same height.

Originating in semi-legendary Scandza (believed to be somewhere in modern Götaland, Sweden), a Gothic population had crossed the Baltic Sea before the second century AD. They reaching Scythia on the coast of the Black Sea in modern Ukraine, where Goths left their archaeological traces in the Chernyakhov culture. In the fifth and sixth centuries, they became divided as the Visigoths and the Ostrogoths, and established powerful successor-states of the Roman Empire in the Iberian peninsula and Italy respectively.[43] Crimean Gothic communities appear to have survived intact in the Crimea until the late-18th century.[44]

Viking and Middle Ages

The Swedish Viking Age lasted roughly between the eighth and 11th centuries. During this period, it is believed that the Swedes expanded from eastern Sweden and incorporated the Geats to the south.[45] It is believed that Swedish Vikings and Gutar mainly travelled east and south, going to Finland, the Baltic countries, Russia, Belarus, Ukraine the Black Sea and further as far as Baghdad. Their routes passed through the Dnieper down south to Constantinople, on which they did numerous raids. The Byzantine Emperor Theophilos noticed their great skills in war and invited them to serve as his personal bodyguard, known as the varangian guard. The Swedish Vikings, called "Rus" are also believed to be the founding fathers of Kievan Rus. The Arabic traveller Ibn Fadlan described these Vikings as following:

I have seen the Rus as they came on their merchant journeys and encamped by the Itil. I have never seen more perfect physical specimens, tall as date palms, blond and ruddy; they wear neither tunics nor caftans, but the men wear a garment which covers one side of the body and leaves a hand free. Each man has an axe, a sword, and a knife, and keeps each by him at all times. The swords are broad and grooved, of Frankish sort.

— [46]

The adventures of these Swedish Vikings are commemorated on many runestones in Sweden, such as the Greece Runestones and the Varangian Runestones. There was also considerable participation in expeditions westwards, which are commemorated on stones such as the England Runestones. The last major Swedish Viking expedition appears to have been the ill-fated expedition of Ingvar the Far-Travelled to Serkland, the region south-east of the Caspian Sea. Its members are commemorated on the Ingvar Runestones, none of which mentions any survivor. What happened to the crew is unknown, but it is believed that they died of sickness.

Kingdom of Sweden

It is not known when and how the 'kingdom of Sweden' was born, but the list of Swedish monarchs is drawn from the first kings who ruled both Svealand (Sweden) and Götaland (Gothia) as one province with Erik the Victorious. Sweden and Gothia were two separate nations long before that into antiquity. It is not known how long they existed, but Beowulf described semi-legendary Swedish-Geatish wars in the sixth century.

Cultural advances

During the early stages of the Scandinavian Viking Age, Ystad in Scania and Paviken on Gotland, in present-day Sweden, were flourishing trade centres. Remains of what is believed to have been a large market have been found in Ystad dating from 600 to 700 AD.[47] In Paviken, an important centre of trade in the Baltic region during the ninth and tenth centuries, remains have been found of a large Viking Age harbour with shipbuilding yards and handicraft industries. Between 800 and 1000, trade brought an abundance of silver to Gotland, and according to some scholars, the Gotlanders of this era hoarded more silver than the rest of the population of Scandinavia combined.[47]

St. Ansgar is usually credited for introducing Christianity in 829, but the new religion did not begin to fully replace paganism until the 12th century. During the 11th century, Christianity became the most prevalent religion, and from 1050 Sweden is counted as a Christian nation. The period between 1100 and 1400 was characterized by internal power struggles and competition among the Nordic kingdoms. Swedish kings also began to expand the Swedish-controlled territory in Finland, creating conflicts with the Rus who no longer had any connection with Sweden.[48]

Feudal institutions in Sweden

Except for the province of Skane, on the southernmost tip of Sweden which was under Danish control during this time, feudalism never developed in Sweden as it did in the rest of Europe.[49] Therefore, the peasantry remained largely a class of free farmers throughout most of Swedish history. Slavery (also called thralldom) was not common in Sweden,[50] and what slavery there was tended to be driven out of existence by the spread of Christianity, the difficulty in obtaining slaves from the lands east of the Baltic Sea, and by the development of cities before the 16th century[51] Indeed, both slavery and serfdom were abolished altogether by a decree of King Magnus IV Eriksson in 1335. Former slaves tended to be absorbed into the peasantry and some became laborers in the towns. Still, Sweden remained a poor and economically backward country in which barter was the means of exchange. For instance, the farmers of the province of Dalsland would transport their butter to the mining districts of Sweden and exchange it there for iron, which they would then take down to the coast and trade the iron for fish they needed for food while the iron would be shipped abroad.[52]

- Minors and Regents

A large number of children inherited the Swedish crown over the course of the kingdom's existence. King Christian II of Denmark ordered a massacre in 1520 of Swedish nobles at Stockholm. This came to be known as the "Stockholm blood bath" and stirred the Swedish nobility to new resistance and, on 6 June (now Sweden's national holiday) in 1523, they made Gustav Vasa their king.[53] This is sometimes considered as the foundation of modern Sweden. Shortly afterwards he rejected Catholicism and led Sweden into the Protestant Reformation. Economically, Gustav Vasa broke the monopoly of the Hanseatic League over Swedish Baltic Sea trade.[54]

The Hanseatic League had been officially formed at Lübeck on the sea coast of Northern Germany in 1356. The Hanseatic League sought civil and commercial privileges from the princes and royalty of the countries and cities along the coasts of the Baltic Sea.[55] In exchange they offered a certain amount of protection. Having their own navy the Hansa were able to sweep the Baltic Sea free of pirates.[56] The privileges obtained by the Hansa included assurances that only Hansa citizens would be allowed to trade from the ports where they were located. They also sought agreement to be free of all customs and taxes. With these concessions, Lübeck merchants flocked to Stockholm, Sweden and soon came to dominate the economic life of that city and made the port city of Stockholm into the leading commercial and industrial city of Sweden.[57] Under the Hanseatic trade two-thirds of Stockholm's imports consisted of textiles and one third of salt. Exports from Sweden consisted of iron and copper.[58]

However, the Swedes began to resent the monopoly trading position of the Hansa (mostly German citizens) and to resent the income they felt they lost to the Hansa. Consequently, when Gustav Vasa or Gustav I broke the monopoly power of the Hanseatic League he was regarded as a hero to the Swedish people. History now views Gustav I as the father of the modern Swedish nation. The foundations laid by Gustav would take time to develop. Furthermore, when Sweden did develop and freed itself from the Hanseatic League and entered its golden era, the fact that the peasantry had traditionally been free meant that more of the economic benefits flowed back to them rather than going to a feudal landowning class.[59] This was not the case in other countries of Europe like Poland where the peasantry was still bound by serfdom and a strong feudalistic land owning system.

Swedish Empire

_en2.png.webp)

During the 17th century Sweden emerged as a European great power. Before the emergence of the Swedish Empire, Sweden was a very poor and scarcely populated country on the fringe of European civilization, with no significant power or reputation. Sweden rose to prominence on a continental scale during the tenure of king Gustavus Adolphus, seizing territories from Russia and Poland–Lithuania in multiple conflicts, including the Thirty Years' War.

During the Thirty Years' War, Sweden conquered approximately half of the Holy Roman states. Gustav Adolphus planned to become the new Holy Roman Emperor, ruling over a united Scandinavia and the Holy Roman states, but he died at the Battle of Lützen in 1632. After the Battle of Nördlingen, Sweden's only significant military defeat of the war, pro-Swedish sentiment among the German states faded. These German provinces excluded themselves from Swedish power one by one, leaving Sweden with only a few northern German territories: Swedish Pomerania, Bremen-Verden and Wismar. The Swedish armies may have destroyed up to 2,000 castles, 18,000 villages and 1,500 towns in Germany, one-third of all German towns.[60]

In the middle of the 17th century Sweden was the third largest country in Europe by land area, only surpassed by Russia and Spain. Sweden reached its largest territorial extent under the rule of Charles X after the treaty of Roskilde in 1658.[61][62] The foundation of Sweden's success during this period is credited to Gustav I's major changes on the Swedish economy in the 16th century, and his introduction of Protestantism.[63] In the 17th century, Sweden was engaged in many wars, for example with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth with both sides competing for territories of today's Baltic states, with the disastrous Battle of Kircholm being one of the highlights.[64] One-third of the Finnish population died in the devastating famine that struck the country in 1696.[65] Famine also hit Sweden, killing roughly 10% of Sweden's population.[66]

The Swedes conducted a series of invasions into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, known as the Deluge. After more than half a century of almost constant warfare, the Swedish economy had deteriorated. It became the lifetime task of Charles' son, Charles XI, to rebuild the economy and refit the army. His legacy to his son, the coming ruler of Sweden Charles XII, was one of the finest arsenals in the world, a large standing army and a great fleet. Sweden's largest threat at this time, Russia, had a larger army but was far behind in both equipment and training.

_-_Nationalmuseum_-_18031.tif.jpg.webp)

After the Battle of Narva in 1700, one of the first battles of the Great Northern War, the Russian army was so severely decimated that Sweden had an open chance to invade Russia. However, Charles did not pursue the Russian army, instead turning against Poland–Lithuania and defeating the Polish king Augustus II and his Saxon allies at the Battle of Kliszow in 1702. This gave Russia time to rebuild and modernize its army.

After the success of invading Poland, Charles decided to make an invasion attempt of Russia which ended in a decisive Russian victory at the Battle of Poltava in 1709. After a long march exposed to cossack raids, Russian Tsar Peter the Great's scorched-earth techniques and the extremely cold winter of 1709, the Swedes stood weakened with a shattered morale and enormously outnumbered against the Russian army at Poltava. The defeat meant the beginning of the end for the Swedish Empire.

Charles XII attempted to invade Norway 1716; however, he was shot dead at Fredriksten fortress in 1718. The Swedes were not militarily defeated at Fredriksten, but the whole structure and organization of the Norwegian campaign fell apart with the king's death, and the army withdrew.

Forced to cede large areas of land in the Treaty of Nystad in 1721, Sweden also lost its place as an empire and as the dominant state on the Baltic Sea. With Sweden's lost influence, Russia emerged as an empire and became one of Europe's dominant nations. As the war finally ended in 1721, Sweden had lost an estimated 200,000 men, 150,000 of those from the area of present-day Sweden and 50,000 from the Finnish part of Sweden.[67]

In the 18th century, Sweden did not have enough resources to maintain its territories outside Scandinavia, and most of them were lost, culminating with the 1809 loss of eastern Sweden to Russia which became the highly autonomous Grand Principality of Finland in Imperial Russia.

In interest of reestablishing Swedish dominance in the Baltic Sea, Sweden allied itself against its traditional ally and benefactor, France, in the Napoleonic Wars. Sweden's role in the Battle of Leipzig gave it the authority to force Denmark-Norway, an ally of France, to cede Norway to the King of Sweden on 14 January 1814 in exchange for northern German provinces, at the Treaty of Kiel. The Norwegian attempts to keep their status as a sovereign state were rejected by the Swedish king, Charles XIII. He launched a military campaign against Norway on 27 July 1814, ending in the Convention of Moss, which forced Norway into a personal union with Sweden under the Swedish crown, which lasted until 1905. The 1814 campaign was the last war in which Sweden participated as a combatant.[68]

Modern history

There was a significant population increase during the 18th and 19th centuries, which the writer Esaias Tegnér in 1833 attributed to "peace, vaccine, and potatoes".[69] Between 1750 and 1850, the population in Sweden doubled. Sweden was hit by the last natural caused famine in Europe, the Famine of 1867-69 killed thousands in Sweden. According to some scholars, mass emigration to America became the only way to prevent famine and rebellion; over 1% of the population emigrated annually during the 1880s.[70] Nevertheless, Sweden remained poor, retaining a nearly entirely agricultural economy even as Denmark and Western European countries began to industrialize.[70][71]

Many looked towards America for a better life during this time. It is believed that between 1850 and 1910 more than one million Swedes moved to the United States.[72] In the early 20th century, more Swedes lived in Chicago than in Gothenburg (Sweden's second largest city).[73] Most Swedish immigrants moved to the Midwestern United States, with a large population in Minnesota, with a few others moving to other parts of the United States and Canada.

Despite the slow rate of industrialization into the 19th century, many important changes were taking place in the agrarian economy because of innovations and the large population growth.[74] These innovations included government-sponsored programs of enclosure, aggressive exploitation of agricultural lands, and the introduction of new crops such as the potato.[74] Because the Swedish peasantry had never been enserfed as elsewhere in Europe,[75] the Swedish farming culture began to take on a critical role in the Swedish political process, which has continued through modern times with modern Agrarian party (now called the Centre Party).[76] Between 1870 and 1914, Sweden began developing the industrialized economy that exists today.[77]

Strong grassroots movements sprung up in Sweden during the latter half of the 19th century (trade unions, temperance groups, and independent religious groups), creating a strong foundation of democratic principles. In 1889 The Swedish Social Democratic Party was founded. These movements precipitated Sweden's migration into a modern parliamentary democracy, achieved by the time of World War I. As the Industrial Revolution progressed during the 20th century, people gradually began moving into cities to work in factories and became involved in socialist unions. A communist revolution was avoided in 1917, following the re-introduction of parliamentarism, and the country saw comprehensive democratic reforms under the joint Liberal-Social Democrat cabinet of Nils Edén and Hjalmar Branting, with universal and equal suffrage to both houses of parliament enacted for men in 1918 and for women in 1919. The reforms were widely accepted by King Gustaf V, who had previously ousted Karl Staaff's elected Liberal government in the Courtyard Crisis because of differences in defence policy.

World Wars

Sweden remained officially neutral during World War I and World War II, although its neutrality during World War II has been disputed.[78][79] Sweden was under German influence for much of the war, as ties to the rest of the world were cut off through blockades.[78] The Swedish government felt that it was in no position to openly contest Germany,[80] and therefore made some concessions.[81] Sweden also supplied steel and machined parts to Germany throughout the war. However, Sweden supported Norwegian resistance, and in 1943 helped rescue Danish Jews from deportation to Nazi concentration camps. Sweden also supported Finland in the Winter War and the Continuation War with volunteers and materiel.

Toward the end of the war, Sweden began to play a role in humanitarian efforts and many refugees, among them many Jews from Nazi-occupied Europe, were saved partly because of the Swedish involvement in rescue missions at the internment camps and partly because Sweden served as a haven for refugees, primarily from the Nordic countries and the Baltic states.[80] Nevertheless, internal and external critics have argued that Sweden could have done more to resist the Nazi war effort, even if risking occupation although doing so would likely have resulted in even greater number of casualties and prevented many humanitarian efforts.[80]

Post-war era

Sweden was officially a neutral country and remained outside NATO or Warsaw pact membership during the Cold War, but privately Sweden's leadership had strong ties with the United States and other western governments.

Following the war, Sweden took advantage of an intact industrial base, social stability and its natural resources to expand its industry to supply the rebuilding of Europe.[82] Sweden was part of the Marshall Plan and participated in the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). During most of the post-war era, the country was governed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party largely in cooperation with trade unions and industry. The government actively pursued an internationally competitive manufacturing sector of primarily large corporations.[83]

.jpg.webp)

Sweden, like countries around the globe, entered a period of economic decline and upheaval, following the oil embargoes of 1973–74 and 1978–79.[84] In the 1980s pillars of Swedish industry were massively restructured. Shipbuilding was discontinued, wood pulp was integrated into modernized paper production, the steel industry was concentrated and specialized, and mechanical engineering was robotized.[85]

Between 1970 and 1990 the overall tax burden rose by over 10%, and the growth was low compared to other countries in Western Europe. The marginal income tax for workers reached over 80%. Eventually government spent over half of the country's gross domestic product. Sweden GDP per capita ranking declined during this time.[83]

Recent history

.jpg.webp)

A bursting real estate bubble caused by inadequate controls on lending combined with an international recession and a policy switch from anti-unemployment policies to anti-inflationary policies resulted in a fiscal crisis in the early 1990s.[86] Sweden's GDP declined by around 5%. In 1992, there was a run on the currency, with the central bank briefly increasing interest to 500%.[87][88]

The response of the government was to cut spending and institute a multitude of reforms to improve Sweden's competitiveness, among them reducing the welfare state and privatising public services and goods. Much of the political establishment promoted EU membership, and the Swedish referendum passed with 52% in favour of joining the EU on 13 November 1994. Sweden joined the European Union on 1 January 1995.

Sweden remains non-aligned militarily, although it participates in some joint military exercises with NATO and some other countries, in addition to extensive cooperation with other European countries in the area of defence technology and defence industry. Among others, Swedish companies export weapons that are used by the American military in Iraq.[89] Sweden also has a long history of participating in international military operations, including most recently, Afghanistan, where Swedish troops are under NATO command, and in EU sponsored peacekeeping operations in Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Cyprus. Sweden held the chair of the European Union from 1 July to 31 December 2009.

Timeline of Swedish history

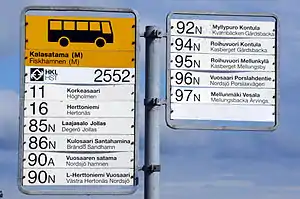

Language

The native language of nearly all Swedes is Swedish (svenska [ˈsvɛ̂nːska] ⓘ) a North Germanic language, spoken by approximately 10 million people,[90] predominantly in Sweden and parts of Finland, especially along its coast and on the Åland islands. It is, to a considerable extent, mutually intelligible with Norwegian and to a lesser extent with spoken Danish (see especially "Classification"). Along with the other North Germanic languages, Swedish is a descendant of Old Norse, the common language of the Germanic peoples living in Scandinavia during the Viking Era. It is the largest of the North Germanic languages by numbers of speakers.

Standard Swedish, used by most Swedish people, is the national language that evolved from the Central Swedish dialects in the 19th century and was well established by the beginning of the 20th century. While distinct regional varieties descended from the older rural dialects still exist, the spoken and written language is uniform and standardized. Some dialects differ considerably from the standard language in grammar and vocabulary and are not always mutually intelligible with Standard Swedish. These dialects are confined to rural areas and are spoken primarily by small numbers of people with low social mobility. Though not facing imminent extinction, such dialects have been in decline during the past century, despite the fact that they are well researched and their use is often encouraged by local authorities.

Genetics

According to recent genetic analysis, both mtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms showed a noticeable genetic affinity between Swedes and other Germanic ethnic groups.[91]

Paternally, through their Y-DNA haplogroups, the Swedes are quite diverse and show strongly of Haplogroup I1d1 at over 40% of the population tested in different studies, followed by R1a1a and R1b1a2a1a1 with over 20% each and haplogroup N1c1 with over 5% at different regional variance. The rest are within haplogroups J and E1b1b1 and other less common ones.[92]

Maternally, through their mtDNA haplogroups, the Swedes show very strongly of haplogroup H at 25–30%, followed by haplogroup U at a 10% or more, with haplogroup J and T, K at around 5% each.

Geographic distribution

The largest area inhabited by Swedes, as well as the earliest known original area inhabited by their linguistic ancestors, is in the country of Sweden, situated on the eastern side of the Scandinavian Peninsula and the islands adjacent to it, situated west of the Baltic Sea in northern Europe. The Swedish-speaking people living in near-coastal areas on the north-eastern and eastern side of the Baltic Sea also have a long history of continuous settlement, which in some of these areas possibly started about a millennium ago. These people include the Swedish-speakers in mainland Finland – speaking a Swedish dialect commonly referred to as Finland Swedish (finlandssvenska which is part of the East-Swedish dialect group) and the almost exclusively Swedish-speaking population of Åland speaking in a manner closer to the adjacent dialects in Sweden than to adjacent dialects of Finland Swedish. Estonia also had an important Swedish minority which persisted for about 650 years on the coast and isles. Smaller groups of historical descendants of 18th–20th-century Swedish emigrants who still retain varying aspects of Swedish identity to this day can be found in the Americas (especially Minnesota and Wisconsin; see Swedish Americans) and in Ukraine.

Currently, Swedes tend to emigrate mostly to the Nordic neighbour countries (Norway, Denmark, Finland), English speaking countries (United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand), Spain, France and Germany.[93]

Historically, the Kingdom of Sweden has been much larger than nowadays, especially during "The Era of Great Power" (Swedish Empire) in 1611–1718. Finland belonged to Sweden until 1809.[94] Since there was no separate Finnish nationality at those times, it is not unusual that sources predating 1809 refer both to Swedes and Finns as "Swedes". This is particularly the case with New Sweden, where some of the Swedish settlers were of Finnish origin.

Questionnaire surveys of Swedish embassies conducted by Swedes Worldwide, a non-profit organization, have shown a steady growth of Swedes living outside Sweden. The 2022 survey indicates an approximate 685,000 Swedes living abroad, up from 660,000 in 2015 and 546,000 in 2011.[95]

| Country | 2011 | 2015 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 100,000 | 150,000 | 179,000 |

| Spain | 90,000 | 90,000 | 104,000 |

| United Kingdom | 90,000 | 90,000 | 100,000 |

| Norway | 80,000 | 90,000 | 39,600 |

| France | 30,000 | 30,000 | 30,000 |

| Germany | 18,000 | 23,000 | 22,500 |

| Finland | 13,000 | 15,000 | 17,500 |

| Denmark | 13,000 | 15,000 | 17,000 |

| Switzerland | 17,000 | 10,000 | 16,000 |

| Italy | 10,000 | 12,000 | 15,500 |

| Australia | 8,000 | 11,000 | 10,000 |

| Belgium | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 |

| Iraq | — | 500 | 10,000 |

| Netherlands | 5,500 | 6,500 | 8,000 |

| Canada | 7,000 | 7,000 | 5,800 |

| Portugal | — | 3,500 | 5,500 |

| Poland | — | 1,500 | 5,500 |

| Chile | 1,000 | 5,000 | 5,000 |

| United Arab Emirates | — | 4,000 | 5,000 |

| Thailand | 10,000 | 20,000 | 4,500 |

| Israel | — | 4,000 | 4,000 |

| Malta | — | 2,000 | 4,000 |

| Austria | — | 3,500 | 3,700 |

| New Zealand | 3,000 | 3,000 | 3,300 |

| Brazil | 2,000 | 4,000 | 3,000 |

| Serbia | — | 4,000 | 3,000 |

| Ireland | 3,500 | 3,500 | 3,000 |

| Iran | — | 1,000 | 3,000 |

| Turkey | — | 1,000 | 3.000 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | — | 500 | 3,000 |

See also

Further reading

- "What Makes the Beautiful Swedish Blonde Look: History and Genetics". Arlen Tanner. Live Scandinavia. 17 July 2019.

References

- "Befolkningsstatistik i sammandrag 1960–2015". 27 March 2016. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Rapo, Markus. "Tilastokeskus – Väestörakenne 2008". tilastokeskus.fi. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- Ewa Hedlund (2011) "Utvandrare.nu – Från emigrant till global svensk Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Föreningen svenskar i världen. p. 42 ISBN 978-91-979795-0-4

- 2000 population and housing census (in Estonian and English). Vol. 2. Statistikaamet (Statistical Office of Estonia). 2021. ISBN 978-9985-74-202-0. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Malitska, Julia (2017). Negotiating Imperial Rule Colonists and Marriage in the Nineteenth-century Black Sea Steppe (PDF) (PhD). Huddinge, Sweden: Södertörn University. ISBN 978-91-87843-93-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder – Results". Factfinder2.census.gov. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- Statistics Canada (8 May 2013). "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- "About us". Londonsvenskar.com. LondonSwedes. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

Approximately 100 000 Swedes live in London and the UK, with about 500 000 Swedish tourists visiting the UK capital annually.

- Personer med innvandringsbakgrunn, etter innvandringskategori, landbakgrunn og kjønn Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine SSB, retrieved 13 July 2015

- "Fakta om Norge". Utlandsjobb.nu. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

90 000 svenskar bor i Norge

- 2006 Australian Census Archived 22 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine Reports 30,375 people of Swedish Ancestry

- "Présentation de la Suède". France Diplomatie : : Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires étrangères. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- "Fakta om Tyskland". Utlandsjobb.nu. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

23 000 svenskar bor i Tyskland.

- "Imigrantes Suecos ao Brasil genealogy project". Geni family tree. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- "TablaPx". Ine.es. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- "Map Analyser". Statistikbanken (in Danish). Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "Swedes in Thailand". Bangkok Post. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- "SEFSTAT" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- "Portugal's Swedish NHR pensioners get the bad news". Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- "Swedish people". Joshua Project. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "statistiche e distribuzione per regione". Tuttitalia.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "Czy Szwedzi uciekają do Polski? Liczba przybywających osób od lat utrzymuje się na stałym poziomie" [Are the Swedes fleeing to Poland? The number of people arriving has remained steady for years]. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019.

- "2018 Census ethnic group summaries | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- "Statistik". Svenskakyrkan.se. Archived from the original on 1 November 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "...Finland has a Swedish-speaking minority that meets the four major criteria of ethnicity, i.e. self-identification of ethnicity, language, social structure and ancestry (Allardt and Starck, 1981; Bhopal, 1997).

- Archived 31 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine...As language is actually the basic or even the only criterion that distinguishes these two groups from each other, it is more correct to speak of Finnish-speakers and Swedish-speakers in Finland instead of Finns and Finland Swedes. Nowadays the most common English term denoting the latter group is 'the Swedish-speaking Finns'.

- "Population and Society". www.stat.fi. Archived from the original on 11 October 2004.

- The identity of the Swedish[-speaking] minority [in Finland] is however clearly Finnish (Allardt 1997:110). But their identity is twofold: They are both Finland Swedes and Finns (Ivars 1987). (Die Identität der schwedischen Minderheit ist jedoch eindeutig finnisch (Allardt 1997:110). Ihre Identität ist aber doppelt: sie sind sowohl Finnlandschweden als auch Finnen (Ivars 1987).) Saari, Mirja: Schwedisch als die zweite Nationalsprache Finnlands. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- "It is not correct to call a nationality a linguistic group or minority, if it has developed culture of its own. If there is not only a community of language, but also of other characteristics such as folklore, poetry and literature, folk music, theater, behavior, etc." "The concept of nation has a different significance as meaning of a population group or an ethnic community, irrespectively of its organization. For instance, the Swedes of Finland, with their distinctive language and culture form a nationality which under the Finnish constitution shall enjoy equal rights with the Finnish nationality". "In Finland this question (Swedish nationality) has been subjected to much discussion. The Finnish majority tries to deny the existence of a Swedish nationality. An example of this is the fact that the statutes always use the concept "'Swedish-speaking' instead of 'Swedish'". Tore Modeen, The cultural rights of the Swedish ethnic group in Finland (Europa Ethnica, 3–4 1999, jg.56)

- "the definition of Swede". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- "OSA – Om svar anhålles". g3.spraakdata.gu.se. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- "OSA – Om svar anhålles". g3.spraakdata.gu.se. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- Noreen, A. Nordens äldsta folk- och ortnamn (i Fornvännen 1920 sid 32).

- "Indogermanisches Etymologisches Woerterbuch [Pokorny] : Query result". 13 June 2011. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011.

- "915 (Svensk etymologisk ordbok)". Runeberg.org. 16 August 2017. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

-

- Malmström, Helena (19 January 2015). "Ancient mitochondrial DNA from the northern fringe of the Neolithic farming expansion in Europe sheds light on the dispersion process". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Royal Society. 370 (1660): 20130373. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0373. PMC 4275881. PMID 25487325.

- Aubin, Hermann. "History of Europe: Barbarian migrations and invasions The Germans and Huns". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). pp. 830–831. Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438129181.

- Sørensen, Marie Louise Stig. "History of Europe: The Bronze Age". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- Ström, Folke: Nordisk Hedendom, Studentlitteratur, Lund 2005, ISBN 91-44-00551-2 (first published 1961) among others, refer to the climate change theory.

- Eriksson, Benny (9 May 2016). "Mytisk extremvinter visade sig stämma". SVT. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (1974). Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology: Sutton Hoo and Other Discoveries. London: Victor Gollancz.

- Goth (people) Archived 2 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- Ingemar Nordgren (2004). "The Well Spring of the Goths: About the Gothic Peoples in the Nordic Countries and on the Continent Archived 17 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine". iUniverse. p. 520 ISBN 0-595-33648-5

- "Sweden". The Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth ed.). bartleby.com. 2000. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009.

- Quoted from: Gwyn Jones. A History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-19-280134-1. Page 164.

- Sawyer, Birgit and Peter Sawyer (1993). Medieval Scandinavia: from Conversion to Reformation, Circa 800–1500. University of Minnesota Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8166-1739-2, pp. 150–153.

- Bagge, Sverre (2005) "The Scandinavian Kingdoms". In The New Cambridge Medieval History. Eds. Rosamond McKitterick et al. Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-36289-X, p. 724: "Swedish expansion in Finland led to conflicts with Rus', which were temporarily brought to an end by a peace treaty in 1323, dividing the Karelian peninsula and the northern areas between the two countries."

- Franklin D. Scott, Sweden: The Nation's History (University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 1977) p. 58.

- Träldom Archived 9 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Nordisk familjebok / Uggleupplagan. 30. Tromsdalstind – Urakami /159–160, 1920. (In Swedish)

- Scott, p. 55.

- Scott, pp. 55–56.

- Scott, p. 121.

- Scott, p. 132.

- Robert S. Hoyt & Stanley Chodorow, Europe in the Middle Ages (Harcourt, Brace & Jovanovich, Inc.: New York, 1976) p. 628.

- John B. Wolfe, The Emergence of European Civilization (Harper & Row Pub.: New York, 1962) pp. 50–51.

- Scott, p. 52.

- Scott

- Scott, pp. 156–157.

- "Population". History Learningsite. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- "A Political and Social History of Modern Europe V.1./Hayes..." Hayes, Carlton J. H. (1882–1964), Title: A Political and Social History of Modern Europe V.1., 2002-12-08, Project Gutenberg, webpage: Infomot-7hsr110 Archived 17 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- However, Sweden's largest territorial extent lasted from 1319 to 1343 with Magnus Eriksson ruling all of the traditional lands of Sweden and Norway.

- "Gustav I Vasa – Britannica Concise" (biography), Britannica Concise, 2007, webpage: EBConcise-Gustav-I-Vasa Archived 21 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Battle of Kircholm 1605". Kismeta.com. Archived from the original on 14 June 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- Finland and the Swedish Empire Archived 9 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Source: U.S. Library of Congress

- Elizabeth Ewan, Janay Nugent (2008) "Finding the family in medieval and early modern Scotland Archived 17 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine". Ashgate Publishing. p. 153 ISBN 0-7546-6049-4

- "Indelta soldater – Indelningsverket (UTF-8)". Algonet.se. 30 May 2012. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "Sweden celebrates 200 years of peace". The Local Sweden. 15 August 2014. Archived from the original on 12 July 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- Magocsi, Paul R.; Multicultural History Society of Ontario (1999), Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples, University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8020-2938-6

- Einhorn, Eric and John Logue (1989). Modern Welfare States: Politics and Policies in Social Democratic Scandinavia. Praeger Publishers, p. 9: "Though Denmark, where industrialization had begun in the 1850s, was reasonably prosperous by the end of the nineteenth century, both Sweden and Norway were terribly poor. Only the safety valve of mass emigration to America prevented famine and rebellion. At the peak of emigration in the 1880s, over 1% of the total population of both countries emigrated annually."

- Koblik, Steven (1975). Sweden's Development from Poverty to Affluence 1750–1970, University of Minnesota Press, pp. 8–9, "In economic and social terms the eighteenth century was more a transitional than a revolutionary period. Sweden was, in light of contemporary Western European standards, a relatively poor but stable country. [...] It has been estimated that 75–80% of the population was involved in agricultural pursuits during the late eighteenth century. One hundred years later, the corresponding figure was still 72%."

- Einhorn, Eric and John Logue (1989), p. 8.

- Beijbom, Ulf (1996). "European emigration: A Review of Swedish Emigration to America". Americanwest.com (Courtesy The House of Emigrants, Växjö, Sweden). Archived from the original on 5 December 2010.

- Koblik, pp. 9–10.

- Sweden: Social and economic conditions Archived 30 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 19 February 2007.

- Koblik, p. 11: "The agrarian revolution in Sweden is of fundamental importance for Sweden's modern development. Throughout Swedish history the countryside has taken an unusually important role in comparison with other European states."

- Koblik, p. 90. "It is usually suggested that between 1870 and 1914 Sweden emerged from its primarily agrarian economic system into a modern industrial economy."

- Koblik, pp. 303–313.

- Nordstrom, p. 315: "Sweden's government attempted to maintain at least a semblance of neutrality while it bent to the demands of the prevailing side in the struggle. Although effective in preserving the country's sovereignty, this approach generated criticism at home from many who believed the threat to Sweden was less serious than the government claimed, problems with the warring powers, ill feelings among its neighbours, and frequent criticism in the postwar period."

- Nordstrom, pp. 313–319.

- Zubicky, Sioma (1997). Med förintelsen i bagaget (in Swedish). Stockholm: Bonnier Carlsen. p. 122. ISBN 91-638-3436-7.

- Nordstrom, pp. 335–339.

- Globalization and Taxation: Challenges to the Swedish Welfare State. By Sven Steinmo.

- Nordstrom, p. 344: "During the last twenty-five years of the century a host of problems plagued the economies of Norden and the West. Although many were present before, the 1973 and 1980 global oil crises acted as catalysts in bringing them to the fore."

- Krantz, Olle and Lennart Schön. 2007. Swedish Historical National Accounts, 1800–2000. Lund: Almqvist and Wiksell International.

- Englund, P. 1990. "Financial deregulation in Sweden." European Economic Review 34 (2–3): 385–393. Korpi TBD. Meidner, R. 1997. "The Swedish model in an era of mass unemployment." Economic and Industrial Democracy 18 (1): 87–97. Olsen, Gregg M. 1999. "Half empty or half full? The Swedish welfare state in transition." Canadian Review of Sociology & Anthropology, 36 (2): 241–268.

- "Sweden's 'Crazy' 500% Interest Rate; Fails to Faze Most Citizens, Businesses; Hike Seen as Short-Term Move to Protect Krona From Devaluation". Highbeam.com. 18 September 1992. Archived from the original on 15 February 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- Lars Jonung; Jaakko Kiander; Pentti Vartia (2009). The Great Financial Crisis in Finland and Sweden. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84844-305-1. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- The Local. "New Swedish weapon in Iraq". Archived from the original on 16 December 2006. Retrieved 23 June 2007.

- "Ethnologue report for Swedish". Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009. gives the number of 8,789,835, but is based on data from 1986. Sweden has currently a population of 9.2 Mio (2008 census), and there are about 290,000 native speakers of Swedish in Finland "Statistics Finland – Population Structure". Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2009. (based on data from 2007), leading to an estimate of about 9 to 10 Mio.

- "Different genetic components in the Norwegian population revealed by the analysis of mtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Haplogroups of the World" (PDF). Scs.uiuc.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2004. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- "Flest svenskar tros bo i USA, Norge och Finland. Därefter följer Danmark, Storbritannien, Spanien och Tyskland". Archived from the original on 30 June 2010.

- "The history of the Finland- Swedes". Svenskfinland. 6 September 2019. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- "Svenskar i världen – Kartläggning 2022" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2022.

External links

- VisitSweden—Sweden's official website for tourism and travel information