Philip III of Spain

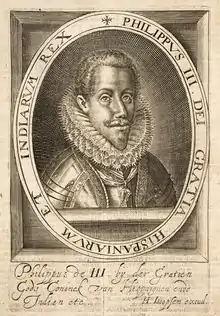

Philip III (Spanish: Felipe III; 14 April 1578 – 31 March 1621) was King of Spain. As Philip II, he was also King of Portugal, Naples, Sicily and Sardinia and Duke of Milan from 1598 until his death in 1621.

| Philip III | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Andrés López Polanco, c. 1617 | |

| King of Spain and Portugal | |

| Reign | 13 September 1598 – 31 March 1621 |

| Predecessor | Philip II of Spain |

| Successor | Philip IV of Spain |

| Born | 14 April 1578 Royal Alcázar of Madrid, Madrid, Spain |

| Died | 31 March 1621 (aged 42) Madrid, Spain |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Habsburg |

| Father | Philip II of Spain |

| Mother | Anna of Austria |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature |  |

| House of Habsburg Spanish line |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

Emperor Charles V (King Charles I) |

|

| Philip II |

| Philip III |

| Philip IV |

| Charles II |

A member of the House of Habsburg, Philip III was born in Madrid to King Philip II of Spain and his fourth wife, his niece Anna, the daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II and Maria of Spain. Philip III later married his cousin Margaret of Austria, sister of Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor.

Although also known in Spain as Philip the Pious,[1] Philip's political reputation abroad has been largely negative. Historians C. V. Wedgwood, R. Stradling and J. H. Elliott have described him, respectively, as an "undistinguished and insignificant man,"[2] a "miserable monarch,"[3] and a "pallid, anonymous creature, whose only virtue appeared to reside in a total absence of vice."[4] In particular, Philip's reliance on his corrupt chief minister, the Duke of Lerma, drew much criticism at the time and afterwards. For many, the decline of Spain can be dated to the economic difficulties that set in during the early years of his reign. Nonetheless, as the ruler of the Spanish Empire at its height and as the king who achieved a temporary peace with the Dutch (1609–1621) and brought Spain into the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) through an (initially) extremely successful campaign, Philip's reign remains a critical period in Spanish history.

Early life

After Philip III's older half-brother Don Carlos died insane, their father Philip II had concluded that one of the causes of Carlos' condition had been the influence of the warring factions at the Spanish court.[5] He believed that Carlos' education and upbringing had been badly affected by this, resulting in his lunacy and disobedience, and accordingly he set out to pay much greater attention to arrangements for his later sons.[5] Philip II appointed Juan de Zúñiga, then Prince Diego's governor, to continue this role for Philip, and chose García de Loaysa as his tutor.[5] They were joined by Cristóbal de Moura, a close supporter of Philip II. In combination, Philip believed, they would provide a consistent, stable upbringing for Prince Philip, and ensure that he would avoid the same fate as Carlos.[6] Philip's education was to follow the model for royal princes laid down by Father Juan de Mariana, focusing on the imposition of restraints and encouragement to form the personality of the individual at an early age, aiming to deliver a king who was neither tyrannical nor excessively under the influence of his courtiers.[6]

Prince Philip appears to have been generally liked by his contemporaries: 'dynamic, good-natured and earnest,' suitably pious, having a 'lively body and a peaceful disposition,' albeit with a relatively weak constitution.[7] The comparison with the memory of the disobedient and ultimately insane Carlos was usually a positive one, although some commented that Prince Philip appeared less intelligent and politically competent than his late brother.[7] Indeed, although Philip was educated in Latin, French, Portuguese and astronomy, and appears to have been a competent linguist,[6] recent historians suspect that much of his tutors' focus on Philip's undeniably pleasant, pious and respectful disposition was to avoid reporting that, languages aside, he was not in fact particularly intelligent or academically gifted.[8] Nonetheless, Philip does not appear to have been naive—his correspondence to his daughters shows a distinctive cautious streak in his advice on dealing with court intrigue.[9]

Philip first met the Marquis of Denia—the future Duke of Lerma—then, a gentleman of the King's chamber, in his early teens.[8] Lerma and Philip became close friends, but Lerma was considered unsuitable by the King and Philip's tutors. Lerma was dispatched to Valencia as a Viceroy in 1595, with the aim of removing Philip from his influence;[8] but after Lerma pleaded poor health, he was allowed to return two years later. By now in poor health himself, King Philip II was becoming increasingly concerned over the prince's future, and he attempted to establish de Moura as a future, trusted advisor to his son, reinforcing de Loaysa's position by appointing him archbishop.[10] The prince received a new, conservative Dominican confessor.[10] The following year, Philip II died after a painful illness, leaving the Spanish Empire to his son (and grandnephew), King Philip III.

Religion, Philip and the role of women at court

Philip married his cousin, Margaret of Austria, on 18 April 1599, a year after becoming king. Margaret, the sister of the future Emperor Ferdinand II, would be one of three women at Philip's court who would apply considerable influence over the King.[11] Margaret was considered by contemporaries to be extremely pious—in some cases, excessively pious, and too influenced by the Church[12]—'astute and very skillful' in her political dealings,[13] although 'melancholic' and unhappy over the influence of the Duke of Lerma over her husband at court.[12] Margaret continued to fight an ongoing battle with Lerma for influence up until her death in 1611. Philip had an 'affectionate, close relationship' with Margaret,[14] and paid her additional attention after they had a son in 1605.[14]

Margaret, alongside Philip's grandmother/aunt, Empress Maria—the Austrian representative to the Spanish court—and Margaret of the Cross, Maria's daughter—formed a powerful, uncompromising Catholic and pro-Austrian voice within Philip's life.[11] They were successful, for example, in convincing Philip to provide financial support to Ferdinand from 1600 onwards.[14] Philip steadily acquired other religious advisors. Father Juan de Santa Maria—confessor to Philip's daughter, doña Maria, was felt by contemporaries to have an excessive influence over Philip at the end of his life,[15] and both he and Luis de Aliaga, Philip's own confessor, were credited with influencing the overthrow of Lerma in 1618. Similarly Mariana de San Jose, a favoured nun of Queen Margaret's, was also criticised for her later influence over the King's actions.[15]

Style of government

The Spanish crown at the time ruled through a system of royal councils. The most significant of these were the Councils of State and its subordinate Council for War, that were in turn supported by the seven professional councils for the different regions, and four specialised councils for the Inquisition, the Military Orders, Finance and the Crusade tax.[16] These councils were then supplemented by small committees, or juntas, as necessary, such as the 'junta of the night' through which Philip II exercised personal authority towards the end of his reign.[17] As a matter of policy, Philip had tried to avoid appointing grandees to major positions of power within his government and relied heavily on the lesser nobles, the so-called 'service' nobility.[17] Philip II had taken the traditional system of councils and applied a high degree of personal scrutiny to them, especially in matters of paperwork, which he declined to delegate—the result was a 'ponderous' process.[18] To his contemporaries, the degree of personal oversight he exercised was excessive; his 'self-imposed role as the chief clerk to the Spanish empire'[19] was not thought entirely appropriate. Philip first started to become engaged in practical government at the age of 15, when he joined Philip II's private committee.[7]

Philip III's approach to government appears to have stemmed from three main drivers. Firstly, he was heavily influenced by the eirenic ideas being circulated in Italian circles in reaction to the new Humanist theories of governance, typified by Machiavelli.[20] Writers such as Girolamo Frachetta, who became a particular favourite of Philip, had propagated a conservative definition of 'reason of state' which centred on exercising a princely prudence and a strict obedience to the laws and customs of the country that one ruled.[21] Secondly, Philip may have shared Lerma's view that the governmental system of Philip II was fast proving impractical and unnecessarily excluded the great nobles of the kingdoms—it had been creaking badly in the last decades of his father's life.[22] Lastly, Philip's own personality and his friendship with Lerma heavily shaped his approach to policy-making. The result was a radical shift in the role of the crown in government from the model of Philip II.

Duke of Lerma as valido

.jpg.webp)

Within a few hours of Philip ascending to the throne, Lerma had been made a royal counsellor by the new king and set about establishing himself as a fully fledged valido, or royal favourite.[23] Lerma, in due course declared a duke, positioned himself as the gateway to the king. All the business of government, Philip instructed, was to arrive in writing and be channeled through Lerma before reaching him.[24] While Philip was not hugely active in government in other ways, once these memoranda, or consulta, had reached him he appears to have been assiduous in commenting on them.[25] Debates in royal councils would now only begin upon the written instruction of the king—again, through Lerma.[26] All members of royal councils were under orders to maintain complete transparency with Lerma as the king's personal representative;[26] indeed, in 1612 the councils were ordered by Philip to obey Lerma as if he were the king.[25] The degree to which Lerma himself played an active role in government has been disputed. Contemporaries were inclined to see Lerma's hand in every action of government; others have since thought Lerma to have 'neither the temperament nor the energy' to impose himself greatly on the actions of government;[27] still others consider Lerma to have carefully attended only those Councils of State that addressed matters of great importance to the king,[28] creating a space for the wider professionalisation of government that had been lacking under Philip II.[29]

This new system of government became increasingly unpopular very quickly. The novel idea of a valido exercising power went against the long-standing popular conception that the king should exercise his powers personally, not through another.[30] Before long, the apparatus of the Spanish government was packed with Lerma's relatives, Lerma's servants and Lerma's political friends, to the exclusion of others.[31] Lerma responded by further limiting his public visibility in politics, avoiding signing and writing documents personally,[32] and constantly stressing that he was, humbly, only working on behalf of his master, Philip III.

Imperial proconsuls

De Lerma's role as royal favourite at court was further complicated by the rise of various 'proconsuls' under Philip III's reign—significant Spanish representatives overseas, who came to exercise independent judgement and even independent policies in the absence of strong leadership from the centre.[33] The challenges to government communication during the period encouraged aspects of this, but the phenomenon was much more marked under Philip III than under either the reign of his father or son.

In the Netherlands, his father Philip II had bequeathed his remaining territories in the Low Countries to his daughter Isabella of Spain and her husband, Archduke Albert, under the condition that if she died without heirs, the province would return to the Spanish Crown. Given that Isabella was notoriously childless, it was clear that this was only intended to be a temporary measure, and that Philip II had envisaged an early revision to Philip III.[34] As a result, Philip's foreign policy in the Netherlands would be exercised through the strong-willed archdukes, but in the knowledge that ultimately the Spanish Netherlands would return to him as king.[35] Meanwhile, the Italian-born Ambrosio Spinola was to perform a crucial role as a Spanish general in the Army of Flanders. Having demonstrated his military prowess at the siege of Ostend in 1603, Spinola rapidly started to propose and implement policies almost independently of the central councils in Madrid,[36] somehow managing to achieve military victories even without central funding from Spain.[37] De Lerma was uncertain of how to deal with Spinola; on the one hand, de Lerma desperately needed a successful military commander in the Netherlands—on the other, de Lerma was contemptuous of Spinola's relatively low origins and scared of his potential to destabilise de Lerma at court.[38] In the years leading to the outbreak of war in 1618, Spinola was working to produce a plan to finally defeat the Dutch, involving an intervention in the Rhineland followed by fresh hostilities aiming to cut the Low Countries in two: portrayed at the time as the 'spider in the web' of Catholic politics in the region, Spinola was operating without significant consultation with Philip in Madrid.[39]

In Italy, a parallel situation emerged. The Count of Fuentes, as governor of Lombardy, exploited the lack of guidance from Madrid to pursue his own highly interventionist policy across north Italy, including making independent offers to support the Papacy by invading the Venetian Republic in 1607.[40] Fuentes remained in power and pursuing his own policies until his death. The Marquis of Villafranca, as governor of Milan, similarly exercised his own considerable judgement on foreign policy. The Duke of Osuna, who had married into the Sandovel family as a close ally of Lerma, again showed significant independence as the Viceroy of Naples towards the end of Philip's reign. In conjunction with the Spanish ambassador to Venice, the influential Marquis of Bedmar, Osuna pursued a policy of raising an extensive army, intercepting Venetian shipping and imposing sufficiently high taxes that threats of a revolt began to emerge. To exacerbate matters, Osuna was found to have prevented the local Neapolitans from petitioning Philip III to complain.[41] Osuna fell from power only when de Lerma had lost his royal favour, and Osuna's negative impact on Philip's plans for intervention in Germany had become intolerable.[41]

Fall of Lerma

From 1612 onwards, and certainly by 1617, the Lerma administration was crumbling. The monopoly of power in the hands of the Lerma's Sandoval family had generated numerous enemies; Lerma's personal enrichment in office had become a scandal; Lerma's extravagant spending and personal debts were beginning to alarm his own son, Cristóbal de Sandoval, Duke of Uceda; lastly, ten years of quiet diplomacy by Fathers Luis de Aliaga, Philip's confessor, and Juan de Santa Maria, Philip's daughter's confessor and a former client of Queen Margaret,[15] had begun to apply personal and religious pressure on the king to alter his method of government.[42] Philip remained close to Lerma, however, and supported him in becoming a cardinal in March 1618 under Pope Paul V, a position which would offer Lerma some protection as his government collapsed.

Lerma fell to an alliance of interests—Uceda, his son, led the attack, aiming to protect his future interests, allied with Don Baltasar de Zúñiga, a well-connected noble with a background in diplomacy across Europe, whose nephew, Olivares was close to the heir to the throne, Prince Philip. Lerma departed for his ducal seat, and for six weeks Philip did nothing; then, in October, Philip signed a decree renouncing the powers of his former valido, and announcing that he would rule in person.[42] Uceda initially took over as the primary voice at court, but without his father's extensive powers, while De Zúñiga became Philip's minister for foreign and military affairs. Philip, while unwilling to move further against Lerma, took politically symbolic action against Lerma's former secretary Rodrigo Calderón, a figure emblematic of the former administration. Calderón, suspected of having killed Philip's wife Queen Margaret by witchcraft in 1611, was ultimately tortured and then executed by Philip for the more plausible murder of the soldier Francisco de Juaras.[43]

Domestic policy

Philip inherited an empire considerably enlarged by his father. On the Iberian Peninsula, Philip II had successfully acquired Portugal in 1580; across Europe, despite the ongoing Dutch revolt, Spanish possessions in Italy and along the Spanish Road appeared secure; globally, the combination of Castilian and Portuguese colonial territories gave a Spanish ruler unparalleled reach from the Americas to the Philippines and beyond through India to Africa.[44]

The challenge for such a ruler was that these territories were, in legal reality, separate bodies, different entities bound together through the 'supraterritorial' royal institutions of the Spanish crown, utilising Castilian nobility as a ruling class.[45] Even within the peninsula itself, Philip would rule through the kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, Valencia and Portugal, the autonomous provinces of Catalonia and Andalusia—all only loosely joined together through the institution of the Castile monarchy and the person of Philip III.[46] Each part had different taxation, privileges and military arrangements; in practice, the level of taxation in many of the more peripheral provinces was less than in Castile, but the privileged position of the Castilian nobility at all senior levels of royal appointment was a contentious issue for the less favoured provinces.

Expulsion of the Moriscos

One of Philip's first domestic changes was the issuing of a decree in 1609 for the expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain, timed to coincide with the declaration of a truce in the war for the Netherlands.[47] The Moriscos were the descendants of those Muslims that had converted to Christianity during the Reconquista of the previous centuries; despite their conversion, they retained a distinctive culture, including many Islamic practices.[48] Philip II had made the elimination of the Morisco threat a key part of his domestic strategy in the south, attempting an assimilation campaign in the 1560s, which had resulted in the revolt that concluded in 1570.[49] In the final years of his rule, Philip's father had reinvigorated efforts to convert and assimilate the Moriscos, but with almost 200,000 in the south of Spain alone, it was clear by the early years of the new century that this policy was failing.[48]

The idea of completely cleansing Spain of the Moriscos was proposed by Juan de Ribera, the Archbishop and Viceroy of Valencia, whose views were influential with Philip III. Philip's eventual decree to expel a nationality that had lived in Spain for over 800 years and was assimilated within it was based less on doctrinal than financial considerations—confiscating the 'wealth' of the Moriscos – which caused jealousy and resentment by other Christians in Spain, especially in Valencia. Financially, the royal treasury stood to gain by seizing the assets of the removed peoples, while in due course those close to the crown would benefit from cheap land or gifts of estates. Estimates vary slightly, but between around 275,000[48] to over 300,000[50] Moriscos were forced out of Spain between 1609 and 1614. To accomplish this, the armada, or navy, and 30,000 soldiers were mobilized with the mission of transporting the families to Tunis or Morocco. Philip intervened in the problematic decision of what to do with Morisco children—should they be allowed to take them to Islamic countries, where they would be brought up as Muslims—and if they were to remain in Spain, what should be done with them? Philip paternalistically decreed that Morisco children under the age of seven could not be taken to Islamic countries, but that any children remaining in Valencia should be free from the threat of enslavement,[51] and rejected some of Ribera's more extreme suggestions.[52]

While popular at the time, and in keeping with earlier policies, this measure significantly damaged the economies of the Kingdom of Valencia, Aragon and Murcia. The supply of cheap labour and the number of rent paying property owners in these areas decreased considerably, as did agricultural outputs.[53] The cultivation of sugarcane and rice had to be substituted for white mulberry, vineyards and wheat.

Economic decline and failed reform

Philip III's reign was marked by significant economic problems across Spain. Famine struck during the 1590s through a sequence of bad harvests, while from 1599 to 1600 and for several years afterwards there was a terrible outbreak of bubonic plague across Spain, killing over 10% of the population.[54] Mateo Alemán, one of the first modern novelists in Europe, captured the despondent mood of the period, describing 'the plague that came down from Castile and the famine that rose from Andalusia' to grip the country.[55] While the failing harvests affected the rural areas most, the plagues reduced the urban population most significantly, in turn reducing the demand for manufactured goods and undermining the economy further.[56] The result was an economically weakened Spain with a rapidly falling population.

Financially, Philip's situation did not appear much better. He had inherited huge debts from his father, Philip II, and an unhelpful tradition that the kingdom of Castile bore the brunt of royal taxation—Castile carried 65% of total imperial costs by 1616.[57] Philip III received no money from the cortes, or parliaments, of Aragon, the Basque provinces or Portugal; Valencia only provided one contribution, in 1604.[57] Philip did not openly challenge this situation, but instead depended more and more heavily on the Castilian cortes; in turn, the cortes increasingly began to tie new grants of money to specific projects, subtly but steadily altering the relationship between the king and cortes.[58] By the financial crisis of 1607, the cortes had even insisted that it be recalled every three years, and that Philip take an oath—on pain of excommunication—to promise that he had spent the royal funds in line with the promises made previously to the cortes.[58]

Philip and Lerma's attempts to resolve this crisis largely failed, and were not helped by the increasing size of the royal household—an attempt to increase royal prestige and political authority[28]—Philip's own household costs rose enormously at a time of falling income.[59] Philip's attempts to issue new currency—in particular the issues of the copper vélon coinage in 1603–04, 1617 and 1621—simply created considerable instability.[57] The costs of the Dutch campaign resulted in Philip's bankruptcy in 1607, and the crown's attempt to resolve this by converting the asiento tax system—high-interest loans owed to tax farmers—into longer-term juros bonds paying a much lower interest, produced a short-term benefit, but at the price of losing financial flexibility during future crises.[57] By 1618, almost all Philip's incoming crown income was already assigned to its various creditors and he had almost no spending discretion left.[57] Financially, the Spanish state had become dominated by Genoese bankers and lenders under Philip II, whose lines of credit had allowed the Spanish state to continue during its moments of financial crisis; under Philip III this process remained unchecked, building up considerable resentment against this foreign influence,[60] some going so far as to term the bankers 'white moors'.[61]

Throughout Philip's reign, a body of analysis of Spain's condition began to emerge through the work of the numerous arbitristas, or commentators, that dominated public discussions from around 1600 through to the 1630s.[62] These different voices focused heavily on the political economy of Spain—the rural depopulation, the diverse and bureaucratic administrative methods, the social hierarchies and corruption, offering numerous, if often contradictory, solutions.[63] Nonetheless, through most of Philip's reign there was no significant attempt at reform—Philip continued to rule in line with local laws and customs. Philip encouraged consolidation of noble estates, selling off large quantities of crown lands to favoured nobles and creditors.[64] There were no attempts to create an equivalent to the French intendant position—the closest equivalent, the corregidor, lacked the strong links to the crown required to overcome local opposition.[64] Only in Philip's final years did reform begin to gain momentum; a reform committee, or Junta de Reformación, was established in Lerma's final months in 1618.[65] Under the incoming administration, including the reformist Baltasar de Zúñiga, this committee ground on, but would only deliver substantial, if ill-fated results, when rejuvenated under Philip IV's reign.

Foreign policy

On his accession, Philip inherited two major conflicts from his father. The first of these, the ongoing and long-running Dutch revolt, represented a serious challenge to Spanish power from the Protestant United Provinces in a crucial part of the Spanish Empire. The second, the Anglo–Spanish War was a newer, and less critical conflict with Protestant England, marked by a Spanish failure to successfully bring its huge military resources to bear on the smaller English military.

Philip's own foreign policy can be divided into three phases. For the first nine years of his reign, he pursued a highly aggressive set of policies, aiming to deliver a 'great victory'.[66] His instructions to Lerma to wage a war of 'blood and iron' on his rebellious subjects in the Netherlands reflects this.[32] After 1609, when it became evident that Spain was financially exhausted and Philip sought a truce with the Dutch, there followed a period of retrenchment; in the background, tensions continued to grow, however, and by 1618 the policies of Philip's 'proconsuls'—men like Spinola, Fuentes, Villafranca, Osuna and Bedmar—were increasingly at odds with de Lerma's policy from Madrid.[33] The final period, in which Philip intervened in the Holy Roman Empire to secure the election of Ferdinand II as Emperor and in which preparations were made for renewed conflict with the Dutch, largely occurred after the fall of de Lerma and the rise of a new, more aggressive set of advisors in the Madrid court.

War with the Dutch, England and the truce of 1609–21

Philip's initial aim was to achieve a decisive 'great victory'[66] in the long-running war against the rebellious Dutch provinces of the Spanish Netherlands, while placing renewed pressure on the English government of Queen Elizabeth I in an effort to terminate English support for their Dutch colleagues. The Spanish armada, or navy, rebuilt in the 1590s, remained effective against the English,[67] but after the failure of the Spanish invasion of Ireland, leading to the defeat at the Battle of Kinsale, Philip reluctantly accepted that further attacks on England were unlikely to succeed.[66] In the Netherlands, a new war strategy resulted in a re-establishment of Spanish power on the north side of the great rivers Meuse and Rhine, stepping up the military pressure on the rebel provinces. The strategy of a 'great victory,' however, began to descend into a financial war of attrition: the Southern Netherlands—still under Spanish control—and the Dutch Republic in the north—dominated by Calvinist Protestants—were both exhausted, and after the 1607 financial crisis, Spain too was unable to pursue the war. Philip III turned to peace negotiations instead; with the accession to the throne of James I of England it became possible to terminate both the war and English support to the Dutch, with the signature in 1604 of the Treaty of London.[68]

The Twelve Years' Truce with the Dutch followed in 1609, which enabled the Southern Netherlands to recover, but it was a de facto recognition of the independence of the Dutch Republic, and many European powers established diplomatic relations with the Dutch. The truce did not stop the commercial and colonial expansion of the Dutch into the Caribbean and the East-Indies, although Spain had tried to impose the liquidation of the Dutch East India Company as a treaty condition. Minor concessions of the Dutch Republic were the scrapping of the plan to create a Dutch West India Company and to stop the harassment of the Portuguese in Asia. Both concessions were temporary as the Dutch soon recommenced preying upon Portuguese interests, which had already led to the Dutch–Portuguese War in 1602 and would continue till 1654. At least with peace in Europe, the Twelve Year's truce gave Philip's regime an opportunity to begin to recover its financial position.

_-_WGA24408.jpg.webp)

With the death of Henry IV of France—a supporter of the war against Spain—a period of instability commenced in the Kingdom of France. In a sequence of aggressive policy moves, and largely without firm direction from Philip, his regional proconsuls of the Duke of Osuna, viceroy of Naples and the Marquess of Villafranca, the Governor of Milan, directed the Spanish policy in Italy that encountered resistance from the Duchy of Savoy and the Republic of Venice. To secure the connection between Milan and the Netherlands a new route was opened through Valtellina, then part of the independent state of the Three Leagues (the present-day canton of Graubünden, Switzerland), and in 1618 the plot of Venice occurred in which the authorities engaged in the persecution of pro-Spanish agents.

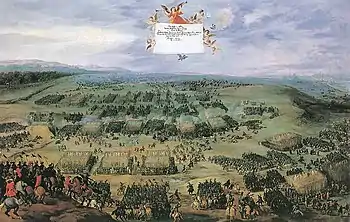

Entry to the Thirty Years' War

In the final years of Philip's reign, Spain entered the initial part of the conflict that would become known as the Thirty Years' War (1618–48). The result was a decisive Spanish victory in the Holy Roman Empire that would lead to a recommencement of the war with the Dutch shortly after Philip's death. Europe was anticipating a fresh election for the position of Emperor upon the likely death of Matthias, who was heirless. Spain and Austria's common Habsburg ancestry influenced Spain's involvement in the convoluted politics of the Empire: on the one hand, Philip had a vested interest in the success of his cousin Ferdinand of Bohemia, who intended to follow Matthias to the throne; on the other, Philip had hopes of appointing one of his own family, such as Prince Philip, to the Imperial throne[69] and worried that a failed bid by Ferdinand might reduce collective Habsburg prestige.[70]

Philip finally chose to intervene behind Ferdinand. Prince Philip had been rejected as unacceptable to the German nobility.[69] Philip had also been increasingly influenced over the years by first Queen Margaret, and later the other, powerful Habsburg women at court, while the incoming set of advisors that replaced de Lerma, especially de Zúñiga, also saw Spain's future as part of a strong alliance with a Habsburg Holy Roman Empire.[71] Finally, by the Oñate treaty of 29 July 1617, Ferdinand made a successful appeal to Philip's self-interest by promising Spain the Habsburg lands in Alsace in return for Spanish support for his election.[72]

Crisis broke out in Ferdinand's kingdom of Bohemia during 1618–19, with a confrontation between Catholic and Protestant factions. Ferdinand asked Spain for help to put down the rebellion; the Protestant rebels turned to Frederick V of the Palatinate as a new ruler and Emperor. The situation in the Empire was in many ways auspicious for Spanish strategy; in the Spanish Netherlands Ambrosio Spinola had been conspiring to find an opportunity to intervene with the Army of Flanders into the Electorate of the Palatinate. The Palatinate was a vital, Protestant set of territories along the Rhine guarding the most obvious route for reinforcements from other Spanish territories to arrive into the rebellious Dutch provinces (through Genoa).[39] France, assumed bound to support Frederick against Ferdinand, was in fact inclined to remain neutral.[73] The Spanish troops headed by Spinola in the Palatinate and by Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly in Bohemia achieved a decisive victory against the Czechs in the Battle of White Mountain in 1620. With the Dutch now vulnerable to a strike through the Rhine valley, a renewed war against the Provinces, with the aim of forcing the Dutch to a more suitable permanent peace, appeared inevitable.

Philip died in 1621 shortly before the recommencement of war—his son, Philip IV, retained his chief foreign policy advisor, de Zúñiga, and an initially highly successful campaign against the Dutch began the same year.

Colonial policy

Chile

In the Americas Philip inherited a difficult situation in Chile, where the Arauco War raged and the local Mapuche succeeded in razing seven Spanish cities (1598–1604). An estimate by Alonso González de Nájera put the toll at 3,000 Spanish settlers killed and 500 Spanish women taken into captivity by Mapuche.[74] In retaliation the proscription against enslaving Indians captured in war was lifted by Philip in 1608.[75][76] This decree was abused when Spanish settlers in Chiloé Archipelago used it to justify slave raids against groups such as the Chono of northwestern Patagonia who had never been under Spanish rule and never rebelled.[77]

Jesuit missionary Luis de Valdivia believed the Mapuche could be voluntarily converted to Christianity only if there was peace.[78][79] To diminish hostilities Valdivia proposed a Defensive War in a letter to Philip. The king supported the idea, issuing a decree that established the Defensive War as an official policy in 1612.[80] By the time Defensive War was established war between Spanish and Mapuche had been going on for 70 years.[80]

These policies were not without criticism. Maestre de campo and corregidor of Concepción Santiago de Tesillo claimed the Defensive War gave the Mapuche a much needed respite to replenish their forces that should have been denied.[81] The Real Audiencia of Santiago opined in the 1650s that slavery of Mapuches was one of the reasons for constant state of war between the Spanish and the Mapuche.[82]

Legacy

Philip III died in Madrid on 31 March 1621, and was succeeded by his son, Philip IV, who rapidly completed the process of removing the last elements of the Sandoval family regime from court. The story told in the memoirs of the French ambassador Bassompierre, that he was killed by the heat of a brasero (a pan of hot charcoal), because the proper official to take it away was not at hand, is a humorous exaggeration of the formal etiquette of the court.

Philip has generally left a poor legacy with historians. Three major historians of the period have described an 'undistinguished and insignificant man',[34] a 'miserable monarch',[83] whose 'only virtue appeared to reside in a total absence of vice'.[84] More generally, Philip has largely retained the reputation of 'a weak, dim-witted monarch who preferred hunting and traveling to governing'.[85]

Unlike Philip IV, whose reputation has improved significantly in the light of recent analysis, Philip III's reign has been relatively unstudied, possibly because of the negative interpretation given to the role of Philip and Lerma during the period.[85] Traditionally, the decline of Spain has been placed from the 1590s onwards; revisionist historians from the 1960s, however, presented an alternative analysis, arguing that in many ways Philip III's Spain of 1621—reinforced with new territories in Alsace, at peace with France, dominant in the Holy Roman Empire, and about to begin a successful campaign against the Dutch—was in a much stronger position than in 1598, despite the poor personal performance of her king during the period.[86] Philip's use of Lerma as his valido has formed one of the key historical and contemporary criticisms against him; recent work[87] has perhaps begun to present a more nuanced picture of the relationship and the institution that survived for the next forty years in Spanish royal government.

Family tree

Like many Habsburgs, Philip III was the product of extensive inbreeding. His father, Philip II, a product of marriage between first cousins, married his niece, Anna of Austria, herself the product of a cousin couple. Philip III in turn married his first cousin once removed, Margaret of Austria. This pattern would continue in the next generation, ultimately culminating in the end of the Spanish Habsburg line in the person of Philip's feeble grandson, Charles II.

Family

Philip married Margaret of Austria, his first-cousin-once-removed. They had 8 children, five of whom survived to adulthood:

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Margaret of Austria (25 December 1584 – 3 October 1611; married in 1599) | |||

| Anne | 22 September 1601 | 20 January 1666 | Queen of France. Married Louis XIII |

| Maria | 1 February 1603 | 1 March 1603 | Died young |

| Philip IV | 8 April 1605 | 17 September 1665 | King of Spain. Married 1) Elisabeth of France (1602-1644) and 2) Mariana of Austria |

| Maria Anna | 18 August 1606 | 13 May 1646 | Holy Roman Empress. Married Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Charles | 15 September 1607 | 30 July 1632 | Died unmarried |

| Ferdinand | 16 May 1609 | 9 November 1641 | A Cardinal |

| Margaret | 24 May 1610 | 11 March 1617 | Died young |

| Afonso | 22 September 1611 | 16 September 1612 | Died young |

See also

References

- Stradling, p. 9.

- Wedgwood, p. 55.

- Stradling, p. 18.

- Elliott, 1963, pp. 300–301.

- Feros, p.16.

- Feros, p.17.

- Feros, p.19.

- Williams, p.38.

- Sánchez, p.101.

- Williams, p.39.

- Sánchez, p.91.

- Sánchez, p.98.

- Sánchez, p.99.

- Sánchez, p.100.

- Sánchez, p.97.

- Williams, p.35.

- Williams, p.34.

- Munck, p.49.

- Mattingly, p.74.

- Tuck, p.121.

- Tuck, p.122.

- Williams, pp.47–8.

- Williams, p.42.

- Feros, p.112.

- Williams, p.104.

- Feros, p.113.

- Williams, p.105.

- Feros, p.110.

- Williams, p.9.

- Feros, pp.117–8.

- Feros, p.133.

- Williams, p.10.

- Polisensky, p.127.

- Wedgwood, p.55.

- In reality, the Archdukes outlived Philip, resulting in the reunification occurring under his son, Philip IV.

- Williams, p.127.

- Williams, p.128.

- Williams, pp.126–7.

- Wedgwood, pp.113–4.

- Parker, 1984, p.153-4.

- Williams, p.245.

- Williams, p.241.

- Williams, p.242.

- Parker, 1984, p.146.

- Zagorin, pp.3–4.

- Parker, 1984, p.61.

- Cruz, p.177.

- Parker, 1984, p.150.

- Zagorin, p.15.

- Perry, p.133.

- Perry, p.148.

- Perry, p.157.

- De Maddalena, p.286.

- Parker, 1985, p.235.

- Parker, 1984, p.147.

- Parker, 1984, pp.146–7.

- Munck, p.51.

- Thompson, p.189.

- Kamen, 1991, p. 200.

- Cruz, p.102.

- Cruz, p.103.

- Parker, 1984, pp.147–8.

- Parker, 1984, p.148.

- Munck, p.50.

- Kamen, p.214.

- Williams, p.125.

- See Goodman (2002), for a thorough account of this revival.

- Parker, 2004, p.212.

- Wedgwood, p.75.

- Wedgwood, p.89.

- Ringrose, p.320.

- Wedgwood, p.57.

- Wedgwood, p.110-1.

- Guzmán, Carmen Luz (2013). "Las cautivas de las Siete Ciudades: El cautiverio de mujeres hispanocriollas durante la Guerra de Arauco, en la perspectiva de cuatro cronistas (s. XVII)" [The captives of the Seven Cities: The captivity of hispanic-creole women during the Arauco's War, from the insight of four chroniclers (17th century)]. Intus-Legere Historia (in Spanish). 7 (1): 77–97. doi:10.15691/07176864.2014.0.94 (inactive 1 August 2023).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - "Philip III, had taken the drastic step of stripping indigenous "rebels" of the customary royal protection against enslavement in 1608, thus making Chile one of the few parts of the empire where slave taking was entirely legal." Reséndez, Andrés. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (pp. 127–128). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

- Valenzuela Márquez, Jaime (2009). "Esclavos mapuches. Para una historia del secuestro y deportación de indígenas en la colonia". In Gaune, Rafael; Lara, Martín (eds.). Historias de racismo y discriminación en Chile (in Spanish). pp. 231–233.

- Urbina Burgos, Rodolfo (2007). "El pueblo chono: de vagabundo y pagano a cristiano y sedentario mestizado". Orbis incognitvs: avisos y legados del Nuevo Mundo (PDF) (in Spanish). Huelva: Universidad de Huelva. pp. 325–346. ISBN 9788496826243.

- Pinto Rodríguez, Jorge (1993). "Jesuitas, Franciscanos y Capuchinos italianos en la Araucanía (1600–1900)". Revista Complutense de Historia de América (in Spanish). 19: 109–147.

- "Misioneros y mapuche (1600–1818)". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- "Guerra Defensiva". Memoria Chilena (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- Baraibar, Alvaro (2013). "Chile como un "Flandes indiano" en las crónicas de los siglos VI y VII". Revista Chilena de Literatura (in Spanish). 85. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- Barros Arana, Diego (2000) [1884]. Historia General de Chile (in Spanish). Vol. IV (2 ed.). Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universitaria. p. 341. ISBN 956-11-1535-2.

- Stradling, p.18.

- Elliott, 1963, pp. 300–301.

- Sánchez, p.92.

- Parker, 1984, p.145.

- In particular, Feros (2006) and Williams' (2006) recent extensive studies of the period, and Sánchez's (1996) analysis of the role of powerful women, often under-reported in historical documents, at Philip's court.

Bibliography

- Carter, Charles H. "The Nature of Spanish Government After Philip II." Historian 26#1 (1963): 1–18. online.

- Cipolla, Carlo M. (ed) The Fontana Economic History of Europe: The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. London: Fontana. (1974)

- Cruz, Anne J. Discourses of Poverty: Social Reform and the Picaresque Novel. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. (1999)

- Davenport, Frances G. European Treaties Bearing on the History of the United States and Its Dependencies. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. (2004)

- Elliott, J. H. Imperial Spain: 1469–1716. London: Penguin. (1963)

- Feros, Antonio. Kingship and Favouritism in the Spain of Philip III, 1598–1621. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (2006)

- Goodman, David. Spanish Naval Power, 1589–1665: Reconstruction and Defeat. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (2002)

- Kamen, Henry. Spain, 1469–1714: A Society of Conflict. Harlow: Pearson Education. (2005)

- Harvey, Leonard Patrick. Muslims in Spain, 1500–1614. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (2005)

- Hoffman, Philip T. and Kathyrn Norberg (eds). Fiscal Crises, Liberty, and Representative Government 1450–1789. (Stanford University Press, 2001)

- Lynch, John. Spain Under the Habsburgs: vol 2 Spain and America (1959) online pp 14–61.

- De Maddalena, Aldo. Rural Europe, 1500–1750. in Cipolla (ed) 1974.

- Mattingly, Garrett. The Armada. New York: Mariner Books. (2005)

- Munck, Thomas. Seventeenth Century Europe, 1598–1700. London: Macmillan. (1990)

- Parker, Geoffrey. Europe in Crisis, 1598–1648. London: Fontana. (1984)

- Parker, Geoffrey. The Dutch Revolt. London: Pelican Books. (1985)

- Parker, Geoffrey. The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567–1659. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (2004)

- Perry, Mary Elizabeth. The Handless Maiden: Moriscos and the politics of religion in early modern Spain. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (2005)

- Polisensky, J. V. The Thirty Years War. London: NEL. (1971)

- Ringrose, David. Spain, Europe and the "Spanish Miracle", 1700–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (1998)

- Sánchez, Magdalena S. Pious and Political Images of a Habsburg Woman at the Court of Philip III (1598–1621). in Sánchez and Saint-Saëns (eds) 1996.

- Sánchez, Magdalena S. and Alain Saint-Saëns (eds). Spanish women in the golden age: images and realities. Greenwood Publishing Group. (1996)

- Stradling, R. A. Philip IV and the Government of Spain, 1621–1665. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (1988)

- Thompson, I. A. A. Castile, Constitionalism and Liberty. in Hoffman and Norburg (eds) 2001.

- Wedgwood, C. V. The Thirty Years War. London: Methuen. (1981)

- Williams, Patrick. The Great Favourite: the Duke of Lerma and the court and government of Philip III of Spain, 1598–1621. Manchester: Manchester University Press. (2006)

- Zagorin, Perez. Rebels and Rulers, 1500–1660. Volume II: Provincial rebellion: Revolutionary civil wars, 1560–1660. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (1992)

Further reading

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XVIII (9th ed.). 1885. p. 746.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Philip III., king of Spain". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- See also Paul C. Allen, Philip III and the Pax Hispanica: The Failure of Grand Strategy (Yale UP: 2000) for an extensive discussion of the foreign policy of Philip III. Allen's is a revisionist work that also argues for a greater role played in international affairs by the Council of State and its leaders in this period rather than by Lerma.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

_-_Lesser.png.webp)