Portuguese Malacca

Portuguese control of Malacca, a city on the Malay Peninsula, spanned the 130 year period (1511–1641) when it was a possession of the Portuguese East Indies. It was conquered from the Malacca Sultanate as part of Portuguese attempts to gain control of trade in the region. Although multiple attempts to conquer it were repulsed, the city was eventually lost to an alliance of Dutch and regional forces, thus entering a period of Dutch rule.

Portuguese Malacca | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1511–1641 | |||||||||

Malacca, shown within modern Malaysia | |||||||||

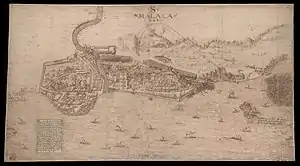

_(14743853356).jpg.webp) Portuguese Malacca in Lendas da India by Gaspar Correia, ca. 1550–1563. | |||||||||

| Status | Portuguese colony | ||||||||

| Capital | Malacca Town | ||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| King of Portugal | |||||||||

• 1511–1521 | Manuel I | ||||||||

• 1640–1641 | John IV | ||||||||

| Captains-major | |||||||||

• 1512–1514 (first) | Rui de Brito Patalim | ||||||||

• 1638–1641 (last) | Manuel de Sousa Coutinho | ||||||||

| Captains-general | |||||||||

• 1616–1635 (first) | António Pinto da Fonseca | ||||||||

• 1637–1641 (last) | Luís Martins de Sousa Chichorro | ||||||||

| Historical era | Age of Imperialism | ||||||||

• Captured | 15 August 1511 | ||||||||

| 14 January 1641 | |||||||||

| Currency | Portuguese real | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Malaysia |

|---|

|

|

|

History

According to the 16th-century Portuguese historian Emanuel Godinho de Erédia, the site of the old city of Malacca was named after the malacca tree (Phyllanthus emblica), fruit-bearing trees along the banks of a river called Airlele (Ayer Leleh). The Airlele river was said to originate from Buquet China (present-day Bukit Cina). Eredia cited that the city was founded by Permicuri (i.e. Parameswara) the first King of Malacca in 1411.

The capture of Malacca

The news of Malacca's wealth attracted the attention of Manuel I, King of Portugal and he sent captain-major Diogo Lopes de Sequeira to make contact with Malacca and sign a trade agreement with its ruler. The first European to reach southeast Asia, Sequeira arrived in Malacca in 1509. Although he was initially well received by Sultan Mahmud Shah, trouble however quickly ensued.[1] The general feeling of rivalry between Islam and Christianity was invoked by a group of Muslims in the sultan's court.[2] The international Muslim trading community convinced Mahmud that the Portuguese were a grave threat. Mahmud subsequently turned on the Portuguese and attacked the four ships in the harbour, killing some and captured several of them, who were then imprisoned in Malacca and violently tortured. As the Portuguese had found in India, conquest would be the only way they could establish themselves in Malacca.[1]

In April 1511, Afonso de Albuquerque set sail from Goa to Malacca with a force of some 1200 men and seventeen or eighteen ships.[1] The governor made a number of demands, one of which was for permission to build a fortress as a Portuguese trading post near the city where they could trade safely.[2] The sultan refused, and after 40 days of fighting, Malacca fell to the Portuguese on 24 August. Sultan Mahmud Shah was forced to flee Malacca. A bitter dispute between Sultan Mahmud and his son Sultan Ahmad also weighed down on the Malaccan side.[1]

Following the defeat of the Malacca Sultanate, Afonso de Albuquerque sought to erect a fort in anticipation of the counterattacks by Sultan Mahmud. A fortress was designed and constructed near a hill, south of the river mouth, on the former site of the mosque. Albuquerque remained in Malacca until November 1511 preparing its defences against any Malay counterattack.[1]

A Portuguese port in a hostile region

.jpg.webp)

Portuguese Malacca faced severe hostility as it was the first European Christian trading settlement in Southeast Asia, being surrounded by numerous emerging native Muslim states. They endured years of conflicts with Malay sultans who wanted to get rid of the Portuguese and reclaim the port town. The sultan made several attempts to retake the capital. He rallied the support from his ally the Sultanate of Demak in Java who, in 1511, agreed to send naval forces to assist. Led by Pati Unus, the sultan of Demak, the combined Malay–Java efforts failed and were fruitless. The Portuguese retaliated and forced the sultan to flee to Pahang. Later, the sultan sailed to Bintan Island and established a new capital there. With a base established, the sultan rallied the disarrayed Malay forces and organized several attacks and blockades against the Portuguese's position. Frequent raids on Malacca caused the Portuguese severe hardship. In 1521 the second Demak campaign to assist the Malay sultan to retake Malacca was launched, however once again failed with the cost of the Demak sultan's life. He was later remembered as Pangeran Sabrang Lor or the Prince who crossed (the Java Sea) to North (Malay Peninsula). The raids helped convince the Portuguese that the exiled sultan's forces must be silenced. A number of attempts were made to suppress the Malay forces, but it was not until 1526 that the Portuguese finally razed Bintan to the ground. The sultan then retreated to Kampar in Riau, Sumatra where he died two years later. He left behind two sons named Muzaffar Shah and Alauddin Riayat Shah II.

Muzaffar Shah was invited by the people in the north of the peninsula to become their ruler, establishing the Sultanate of Perak. Meanwhile, Mahmud's other son, Alauddin succeeded his father and made a new capital in the south. His realm was the Johor Sultanate, the successor of Malacca.

Several attempts to remove Malacca from Portuguese rule were made by the sultan of Johor. A request sent to Java in 1550 resulted in Queen Kalinyamat, the regent of Jepara, sending 4,000 soldiers aboard 40 ships to meet the Johor sultan's request to take Malacca. The Jepara troops later joined forces with the Malay alliance and managed to assemble around 200 warships for the upcoming assault. The combined forces attacked from the north and captured most of Malacca, but the Portuguese managed to retaliate and force back the invading forces. The Malay alliance troops were thrown back to the sea, while the Jepara troops remained on shore. Only after their leaders were slain did the Jepara troops withdraw. The battle continued on the beach and in the sea resulting in more than 2,000 Jepara soldiers being killed. A storm stranded two Jepara ships on the shore of Malacca, and they fell prey to the Portuguese. Fewer than half of the Jepara soldiers managed to leave Malacca.

In 1568, Prince Husain Ali I Riayat Syah from the Sultanate of Aceh launched a naval attack to oust the Portuguese from Malacca, but this once again ended in failure. In 1574 a combined attack from Aceh Sultanate and Javanese Jepara tried again to capture Malacca from the Portuguese, but ended in failure due to poor coordination.

Competition from other ports such as Johor saw Asian traders bypass Malacca and the city began to decline as a trading port.[3] Rather than achieving their ambition of dominating it, the Portuguese had fundamentally disrupted the organisation of the Asian trade network. Rather than being a centralised port of regional exchange, and having been made an authority to police the Strait of Malacca that ensured safety for commercial traffic, trade was instead scattered over a number of ports that experienced bitter warfare among the Straits.[3]

Chinese reaction

_(14578526689).jpg.webp)

Malacca harboured a community of Chinese merchants, probably from Fujian and other sites, who left China in defiance of Ming laws.[4] They were probably not treated well by the sultan, as all or almost all supported the Portuguese and helped them establish relations with neighbouring countries.[5] They had much to gain both from the protection and connections the Portuguese could offer.[6]

China was first contacted in 1513 by Jorge Álvares, who sailed from Malacca in a fleet of five junks and set foot on an island in the Pearl River Delta, and erected a padrão. He was followed by Rafael Perestrello, who landed in continental China proper and traded profitably at Guangzhou. The protection which Albuquerque provided to the resident Chinese merchants ensured that they were well received.

When on 17 June 1517 a fleet of eight ships under the command of Fernão Peres de Andrade reached Guangzhou with an embassy from King Manuel of Portugal, the ambassador Tomé Pires was disembarked with pomp and circumstance and well received by the Chinese authorities who came to see him with great ceremony.[7][8] Pires and his companions received one of the best houses in the city and received frequent visits from distinguished residents.[9][10] Andrade moved his ships to the Island of Tamão, where he obtained authorization from the Ming authorities to open a trade post and declared that anyone who had demands on the Portuguese should appeal to him, which gave the Chinese a high opinion of the integrity of the Portuguese.[11][12]

Pires reached Beijing in January 1521 but an ambassador from Sultan Mahmud appealed to Emperor Zhengde for aid against the Portuguese.[13] Zhengde died shortly afterwards and his successor Jianjing ruled that the Portuguese embassy would be held hostage at Guangzhou, until the Portuguese had restored the city to Sultan Mahmud.[14] Most or all the members of the embassy were robbed of their belongings and imprisoned, many dying in brutal captivity or executed and Portuguese presence in China banned, though many Portuguese continued to sail from Malacca to engage in trade or smuggling.[15]

With gradual improvement of relations and aid given against the Wokou pirates along China's shores, by 1557 Ming China finally agreed to allow the Portuguese to settle at Macau.[16] The Malay Sultanate of Johor also improved relations with the Portuguese and fought alongside them against the Aceh Sultanate.

Dutch conquest and the end of Portuguese Malacca

By the early 17th century, the Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC) began contesting Portuguese power in the East. At that time, the Portuguese had transformed Malacca into an impregnable fortress, the Fortaleza de Malaca, controlling access to the sea lanes of the Straits of Malacca and the spice trade in the region, where it repulsed an attack from Aceh in 1568. The Dutch started by launching small incursions and skirmishes against the Portuguese. The first serious attempt was the siege of Malacca in 1606 by the third VOC fleet from Holland with eleven ships, commanded by Admiral Cornelis Matelief de Jonge that led to the naval battle of Cape Rachado. Although the Dutch were routed, the Portuguese fleet of Martim Afonso de Castro, the Viceroy of Goa, suffered heavier casualties and the battle rallied the forces of the Sultanate of Johor into an alliance with the Dutch and later on with the Aceh Sultanate.

Around that same time period, the Sultanate of Aceh had grown into a regional power with a formidable naval force and regarded Portuguese Malacca as potential threat. In 1629, Iskandar Muda of the Aceh Sultanate sent several hundred ships to attack Malacca, but the mission was a devastating failure. According to Portuguese sources, all of his ships were destroyed and lost some 19,000 men in the process.[17]

The Dutch with their local allies assaulted and finally wrested Malacca from the Portuguese in January 1641. This combined Dutch-Johor-Aceh efforts effectively destroyed the last bastion of Portuguese power, reducing their influence in the archipelago. The Dutch settled in the city as Dutch Malacca, however the Dutch had no intention to make Malacca their main base, and concentrated on building Batavia (today Jakarta) as their headquarters in the orient instead. The Portuguese ports in the spice-producing areas of Mollucas also fell to the Dutch in the following years. With these conquests, the last Portuguese colonies in Asia remained confined to Portuguese Timor, Goa, Daman and Diu in Portuguese India and Macau until the 20th century.

Fortress of Malacca

The early core of the fortress system was a quadrilateral tower called Fortaleza de Malaca. Measurement was given as 10 fathoms per side with a height of 40 fathoms. It was constructed at the foot of the fortress hill, next to the sea. To its east was constructed a circular wall of mortar and stone with a well in the middle of the enclosure.

Over the years, constructions began to fully fortify the fortress hill. The pentagonal system began at the farthest point of the cape near south east of the river mouth, towards the west of the Fortaleza. At this point two ramparts were built at right angles to each other lining the shores. The one running northward toward the river mouth was 130 fathoms in length to the bastion of São Pedro while the other one ran for 75 fathoms to the east, curving inshore, ending at the gate and bastion of Santiago.

From the bastion of São Pedro the rampart turned north east 150 fathoms past the Custom House Terrace gateway ending at the northernmost point of the fortress, the bastion of São Domingos. From the gateway of São Domingos, an earth rampart ran south-easterly for 100 fathoms ending at the bastion of the Madre de Deus. From here, beginning at the gate of Santo António, past the bastion of the Virgins, the rampart ended at the gateway of Santiago. Overall, the city enclosure was 655 fathoms and 10 palms (short) of a fathom.

Gateways

Four gateways were built for the city:

- Porta de Santiago

- The gateway of the Custom House Terrace

- Porta de São Domingos

- Porta de Santo António

Of these four gateways only two were in common use and open to traffic: the Gate of Santo António linking to the suburb of Yler and the western gate at the Custom House Terrace, giving access to Tranqueira and its bazaar.

Destruction

After almost 300 years of existence, in 1806, the British, unwilling to maintain the fortress and wary of letting other European powers take control of it, ordered its slow destruction. The fort was almost totally demolished but for the timely intervention of Sir Stamford Raffles visiting Malacca in 1810. The only remnants of the earliest Portuguese fortress in Southeast Asia is the Porta de Santiago, now known as the A Famosa.

The city of Malacca during the Portuguese Era

Malacca was the most thoroughly described city in south-east Asia during the 16th and 17th century as a result of it being under Portuguese control.[18] Outside of the fortified town centre lie the three suburbs of Malacca. The suburb of Upe (Upih), generally known as Tranqueira (modern day Tengkera) from the rampart of the fortress. The other two suburb were Yler (Hilir) or Tanjonpacer (Tanjung Pasir) and the suburb of Sabba.

Tranqueira

Tranqueira was the most important suburb of Malacca. The suburb was rectangular in shape, with a northern walled boundary, the straits of Malacca to the south and the river of Malacca (Rio de Malaca) and the fortaleza's wall to the east. It was the main residential quarters of the city. However, in war, the residents of the quarters would be evacuated to the fortress. Tranqueira was divided into a further two parishes, São Tomé and São Estêvão. The parish of S.Tomé was called Campon Chelim (Malay: Kampung Keling). It was described that this area was populated by the Chelis of Choromandel. The other suburb of São Estêvão was also called Campon China (Kampung Cina).

Erédia described the houses as made of timber but roofed by tiles. A stone bridge with sentry crosses the river Malacca to provide access to the Malacca Fortress via the eastern Custome House Terrace. The centre of trade of the city was also located in Tranqueira near the beach on the mouth of the river called the Bazaar of the Jaos (Jowo/Jawa i.e. Javanese). In the present day, this part of the city is called Tengkera.

Yler

The district of Yler (Hilir) roughly covered Buquet China (Bukit Cina) and the south-eastern coastal area. The Well of Buquet China was one of the most important water sources for the community. Notable landmarks included the Church of the Madre De Deus and the Convent of the Capuchins of São Francisco. Other notable landmarks included Buquetpiatto (Bukit Piatu). The boundaries of this unwalled suburb were said to extend as far as Buquetpipi and Tanjonpacer.

Tanjonpacer (Malay: Tanjung Pasir) was later renamed Ujong Pasir. A community descended from Portuguese settlers is still located here in present-day Malacca. However, this suburb of Yler is now known as Banda Hilir. Modern land reclamations (for the purpose of building the commercial district of Melaka Raya) have, however, denied Banda Hilir the access to the sea that it formerly had.

Sabba

The houses of this suburb were built along the edges of the river. Some of the original Muslim Malay inhabitants of Malacca lived in the swamps of nypeiras tree, where they were known to make nypa (nipah) wine by distillation for trade. This suburb was considered the most rural, being a transition to the Malacca hinterland, where timber and charcoal traffic passed through into the city. Several Christian parishes also lay outside the city along the river; São Lázaro, Our Lady of Guadalupe, Our Lady of Hope. While Muslim Malays inhabited the farmlands deeper into the hinterland.

In later periods of Dutch, British and modern day Malacca, the name of Sabba was made obsolete. However, its area encompassed parts of what is now Banda Kaba, Bunga Raya and Kampung Jawa within the modern city centre of Malacca.

Portuguese immigration

_(14803673703).jpg.webp)

Portuguese residents were separated into five major subgroups:[19]

- Soldados, or the soldier class consisting of single men whose duty it was to defend the city if it were to be under attack.

- Casados, or settlers made up of married settlers. These group of people were directly ruled under the Portuguese formal administration and were made up of fidalgos, retired soldados and lower class citizens who migrated to these foreign lands. Since the composition was disproportionately male, these settlers wound up marrying local Asian natives, leading to children of interracial descent.[20]

- Moradores, or informal settlers who were not under the purview of the formal administration, settling in regions outside of the Portuguese formal eye with Portuguese permission. They were often merchants by profession and established long-term settlements.

- Ministrios, or crown-appointed officials meant for short term-stay. This included the captain-major. Other officials included the ouvidor (crown magistrate) and vedor da fazenda (financial superintendent).

- Religioso, or ecclesiastical class. These were made of Catholic officials sent from with papal blessing to the Bishopric of Malacca which was placed under the purview of the Archbishopric in Goa, established in 1557. The catholic priests were made of the Capuchins, Augustinians and Dominican orders.[21] Malacca was also used as an intermediary stop for Jesuit priests heading to Japan and China, most famous of whom was Francis Xavier.[22]

The Portuguese also shipped over many Órfãs do Rei to Portuguese colonies overseas in Africa and India, and also to Portuguese Malacca. Órfãs do Rei literally translates to "Orphans of the King", and they were Portuguese girl orphans sent to overseas colonies to marry Portuguese settlers.

Portuguese administration of Malacca

Portuguese Malacca was placed under the purview of the Estado da Índia, based in Goa with its governor/viceroy overseeing its rule. Malacca itself was administered by the captain-major whose office was located inside the Fortaleza.

In 1552, Malacca was granted a charter to become a camara (city)[23] equipped with its own Senado de Camara which normally consisted of fidalgos, procuradores dos mesteres (trade guild representatives) and citizens acting on behalf of marginalised groups.[24] The camara represented the voices and interests of the casados who would use it as a medium of communication between themselves and the Portuguese Crown.

Additionally, the other major organisation present in the city was the Misericordia or the House of Mercy which was a fraternity dedicated to providing aid, medicine and rudimentary education to the Christians of Malacca regardless of background. The body of administration was called the mesa and headed by a provedor. They also acted as financial executors for those who willed their assets to the Misericordia.

With regards to native matters, the administrative structure of Malacca pre-conquest remained largely unchanged. Afonso de Albuquerque initially wanted the sultan to return and rule under the Portuguese eye, to no avail.[25] The posts of bendahara, temenggung and shahbandar were maintained and appointed from among the non-muslims of Malacca.

In 1571, an attempt was made by Sebastian I to establish three separate entities of his Asian colonial holdings with Malacca being one sector under its own governor, though this effort did not come to fruition.[26]

According to Eredia in 1613, Malacca was administered by a governor (a captain-major), who was appointed for a term of three-years, as well as a bishop and church dignitaries representing the episcopal see, municipal officers, royal officials for finance and justice and a local native bendahara to administer the native Muslims and foreigners under the Portuguese jurisdiction.

| No. | Captain Major | From | Until | Monarch |

| 1 | Ruy de Brito Patalim | 1512 | 1514 | Manuel I |

| 2 | Jorge de Alburquerque (1st time) | 1514 | 1516 | |

| 3 | Jorge de Brito | 1516 | 1517 | |

| 4 | Nuno Vaz Pereira | 1517 | 1518 | |

| 5 | Alfonso Lopes da Costa | 1518 | 1520 | |

| 6 | Jorge de Alburquerque (2nd time) | 1521 | 1525 | Manuel I John III |

| 7 | Pedro Mascarenhas | 1525 | 1526 | John III |

| 8 | Jorge Cabral | 1526 | 1528 | |

| 9 | Pero de Faria | 1528 | 1529 | |

| 10 | Garcia de Sà (1st time) | 1529 | 1533 | |

| 11 | Dom Paulo da Gama | 1533 | 1534 | |

| 12 | Dom Estêvão da Gama | 1534 | 1539 | |

| 13 | Pero de Faria | 1539 | 1542 | |

| 14 | Ruy Vaz Pereira | 1542 | 1544 | |

| 15 | Simão Botelho | 1544 | 1545 | |

| 16 | Garcia de Sà (2nd time) | 1545 | 1545 | |

| 17 | Simão de Mello | 1545 | 1548 | |

| 18 | Dom Pedro da Silva da Gama | 1548 | 1552 | |

| 19 | Licenciado Francisco Alvares | 1552 | 1552 | |

| 20 | Dom Alvaro de Ata de Gama | 1552 | 1554 | |

| 21 | Dom Antonio de Noronha | 1554 | 1556 | |

| 22 | Dom João Pereira | 1556 | 1557 | |

| 23 | João de Mendonça | 1557 | 1560 | John III Sebastian I |

| 24 | Francisco Deça | 1560 | 1560 | Sebastian I |

| 25 | Diogo de Meneses | 1564 | 1567 | |

| 26 | Leonis Pereira | 1567 | 1570 | |

| 27 | Francisco da Costa | 1570 | 1571 | |

| 28 | António Moniz Barreto | 1571 | 1573 | |

| 29 | Miguel de Castro | 1573 | 1573 | |

| 30 | Leonis Pereira ou Francisco Henriques de Meneses | 1573 | 1574 | |

| 31 | Tristão Vaz da Veiga | 1574 | 1575 | |

| 32 | Miguel de Castro | 1575 | 1577 | |

| 33 | Aires de Saldanha | 1577 | 1579 | Sebastian I |

| 34 | João da Gama | 1581 | 1582 | Philip I |

| 35 | Roque de Melo | 1582 | 1584 | |

| 36 | João da Silva | 1584 | 1587 | |

| 37 | João Ribeiro Gaio | 1587 | 1587 | |

| 38 | Nuno Velho Pereira | 1587 | 15xx | |

| 39 | Diogo Lobo | 15xx | 15xx | |

| 40 | Pedro Lopes de Sousa | 15xx | 1594 | |

| 41 | Francisco da Silva Meneses | 1597 | 1598 | |

| 42 | Martim Afonso de Melo Coutinho | 1598 | 1599 | Philip I |

| 43 | Fernão de Albuquerque | 1599 | 1603 | Phillip II |

| 44 | André Furtado de Mendonça | 1603 | 1606 | |

| 45 | António de Meneses | 1606 | 1607 | |

| 46 | Francisco Henriques | 1610 | 1613 | |

| 47 | Gaspar Afonso de Melo | 1613 | 1615 | |

| 48 | João Calado de Gamboa | 1615 | 1615 | |

| 49 | António Pinto da Fonseca | 1615 | 1616 | |

| 50 | João da Silveira | 1617 | 1617 | |

| 51 | Pedro Lopes de Sousa | 1619 | 1619 | |

| 52 | Filipe de Sousa ou Francisco Coutinho | 1624 | 1624 | Phillip III |

| 53 | Luis de Melo | 162. | 1626 | |

| 54 | Gaspar de Melo Sampaio | 16xx | 1634 | |

| 55 | Álvaro de Castro | 1634 | 1635 | |

| 56 | Diogo de Melo e Castro | 1630 | 1633 | |

| 57 | Francisco de Sousa de Castro | 1630 | 1636 | |

| 58 | Diogo Coutinho Docem | 1635 | 1637 | |

| 59 | Manuel de Sousa Coutinho | 1638 | 1641 | Phillip III |

Military history

| Year | Event |

| 1511 | Conquest of Malacca |

| 1520 | Battle of Pago |

| 1521 | Battle of Bintan, Battle of Aceh |

| 1522 | Pedir Expedition |

| 1523 | Battle of Muar river |

| 1524 | Siege of Pasai |

| 1525 | Battle of Lingga |

| 1526 | Siege of Bintan |

| 1528 | Battle of Aceh |

| 1535 | Battle of Ugentana |

| 1536 | Second Battle of Ugentana |

| 1547 | Battle of Perlis River |

| 1568 | Siege of Malacca |

| 1569 | Battle of Aceh |

| 1570 | First Battle of Formoso River |

| 1573 | Siege of Malacca |

| 1574 | Siege of Malacca |

| 1575 | Siege of Malacca |

| 1587 | Siege of Johor |

| 1606 | Battle of Aceh, Siege of Malacca, Battle of Cape Rachado |

| 1607 | Johor expedition |

| 1615 | Second Battle of Formoso River |

| 1629 | Battle of Duyon River |

| 1641 | Siege of Malacca |

Gallery

Currency

Portuguese Malacca soldo. Reign of Manuel I.

Portuguese Malacca soldo. Reign of Manuel I. Portuguese Malacca bastardo. Reign of Manuel I.

Portuguese Malacca bastardo. Reign of Manuel I._-_Portuguese_Malacca_(Dom_Joao_III)_-_Scott_Semans_03.jpg.webp) Portuguese Malacca tin dinheiro. Reign of John III

Portuguese Malacca tin dinheiro. Reign of John III_-_Portuguese_Malacca_(Dom_Joao_III)_-_Scott_Semans_01.jpg.webp) Portuguese Malacca tin dinheiro. Reign of John III

Portuguese Malacca tin dinheiro. Reign of John III_-_Portuguese_Malacca_(Dom_Joao_III)_-_Scott_Semans_02.jpg.webp) Portuguese Malacca tin dinheiro. Reign of John III

Portuguese Malacca tin dinheiro. Reign of John III_-_Portuguese_Malacca_(Dom_Sebastiao_I)_-_Scott_Semans.jpg.webp) Portuguese Malacca tin soldo. Reign of Sebastian.

Portuguese Malacca tin soldo. Reign of Sebastian._-_Portuguese_Malacca_(Dom_Sebastiao_I)_-_Scott_Semans.jpg.webp) Portuguese Malacca tin dinheiro. Reign of Sebastian.

Portuguese Malacca tin dinheiro. Reign of Sebastian.

See also

References

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan. p. 23. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- Mohd Fawzi bin Mohd Basri; Mohd Fo'ad bin Sakdan; Azami bin Man (2002). Kurikulum Bersepadu Sekolah Menengah Sejarah Tingkatan 1. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. p. 95. ISBN 983-62-7410-3.

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1300, 2nd Edition. London: Macmillan. pp. 23–24. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- Roderich Ptak (2004). "Reconsidering Melaka and Central Guangdong". In Peter Borschberg (ed.). Iberians in the Singapore-Melaka area and adjacent regions (16th to 18th century). Vol. 14 of South China and maritime Asia (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 11. ISBN 3-447-05107-8. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- Roderich Ptak (2004). "Reconsidering Melaka and Central Guangdong". In Peter Borschberg (ed.). Iberians in the Singapore-Melaka area and adjacent regions (16th to 18th century). Vol. 14 of South China and maritime Asia (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 13. ISBN 3-447-05107-8. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- Roderich Ptak (2004). "Reconsidering Melaka and Central Guangdong". In Peter Borschberg (ed.). Iberians in the Singapore-Melaka area and adjacent regions (16th to 18th century). Vol. 14 of South China and maritime Asia (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 12. ISBN 3-447-05107-8. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- J. Gerson da Cunha: Materials for the History of Oriental Studies Amongst the Portuguese in Atti del IV Congresso Internazionale degli Orientalisti, 1881, Florence, p. 214. "His landing was attended with much pomp and circumstance, the fleet greeted him with a salute, the Chinese authorities came in solemn processions to receive him and he was allotted for his residence the best kiosk in the city".

- Zhidong Hao (2011). Macau History and Society (illustrated ed.). Hong Kong University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-988-8028-54-2. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

In 1517, the viceroy of Goa, Lopo Soares de Albergaria, sent a fleet of eight ships to China, led by Fernão Peres de Andrade. This was a successful expedition and the Portuguese were able to establish good relations with the Chinese, even though there were some serious misunderstandings at first.

- Juan González de Mendoza: The History of the Great and Mighty Kingdom of China and the Situation Thereof, volume 1, 1853, Hakluyt Society, xxxiii.

- Ljungstedt, 1836, p. 92.

- Juan González de Mendoza: The History of the Great and Mighty Kingdom of China and the Situation Thereof, volume 1, 1853, Hakluyt Society, xxxiv.

- Frederick Charles Danvers: The Portuguese in India, volume I, London, W. H. Allen & Co. Limited, 1894, p. 338.

- Sir Andrew Ljungstedt: An Historical Sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China, Boston, James Munroe & Cp, 1836, p. 93.

- Ljungstedt, 1836, p. 93.

- Armando Cortesão: A Propósito do Ilustre Boticário Tomé Pires in Esparsos volume II, 1974, p. 206.

- Wills, John E., Jr. (1998). "Relations with Maritime Europe, 1514–1662," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 2, 333–375. Edited by Denis Twitchett, John King Fairbank, and Albert Feuerwerker. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24333-5, 343–344.

- Monteiro, Saturnino (2010). Batalhas e Combates da Marinha Portuguesa. Lisbon: Livraria Sá da Costa Editora. ISBN 978-972-562-323-7.

- Pierre Yves Manguin: Of Fortresses and Galleys: The 1568 Acehnese Siege of Malacca, After a Contemporary Birds Eye View, 1988, p. 607.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (10 April 2012). The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500–1700: A Political and Economic History. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 230–231. doi:10.1002/9781118496459. ISBN 978-1-118-49645-9.

- Disney, A. R. (2009). A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire: From Beginnings to 1807: Volume 2: The Portuguese Empire. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511813337. ISBN 978-0-521-40908-7.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (2012). The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500–1700 A Political and Economic History (2., Auflage ed.). New York, NY. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-118-27401-9. OCLC 894714765.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sar Desai, D. R. “The Portuguese Administration in Malacca, 1511–1641.” Journal of Southeast Asian History, vol. 10, no. 3, 1969, pp. 501–512., doi:10.1017/S0217781100005056.

- South East Asia, Colonial History: Imperialism before 1800. United Kingdom, Routledge, 2001. p.163

- Boxer, C. R. (1973), The Portuguese seaborne empire 1415–1825, Penguin, pp. 273–280

- Disney, A. R. (2009). A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire: From Beginnings to 1807: Volume 2: The Portuguese Empire. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 164. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511813337. ISBN 978-0-521-40908-7.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (2012). The Portuguese empire in Asia, 1500–1700: a political and economic history (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-118-49645-9. OCLC 779165225.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)