Prostate cancer

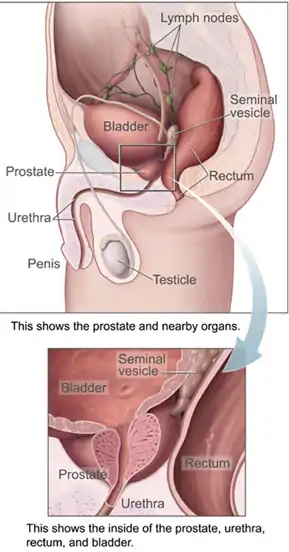

Prostate cancer is the uncontrolled growth of cells in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system just below the bladder. Early prostate cancer usually causes no symptoms. As the cancer develops, one or more tumors can damage nearby organs causing erectile dysfunction, blood in the urine or semen, and trouble urinating. For some patients, the cancer eventually spread to other areas of the body, particularly the bones and lymph nodes. There, tumors cause severe bone pain, leg weakness or paralysis, and eventually death.

| Prostate cancer | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Prostate carcinoma |

| |

| Location of the prostate | |

| Specialty | Oncology, urology |

| Symptoms | Typically none. Sometimes trouble urinating, erectile dysfunction, or pain in the back/pelvis. |

| Usual onset | Age > 40 |

| Risk factors | Older age, family history, race |

| Diagnostic method | PSA test followed by tissue biopsy |

| Differential diagnosis | Benign prostatic hyperplasia |

| Treatment | Active surveillance, prostatectomy, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, chemotherapy |

| Prognosis | Depends on stage, five-year survival rate 97%[1] |

| Frequency | Around 1.2 million new cases per year[2] |

| Deaths | Around 350,000 per year[2] |

Most cases of prostate cancer are detected after screening tests – typically blood tests for levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) – indicate unusual growth of prostate tissue. A definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy of the prostate, which is examined by a pathologist under a microscope. If cancer is present, the pathologist assigns a Gleason score of 6 to 10, with higher scores representing a more dangerous cancer disease. Medical imaging is performed to look for cancer spread outside the prostate. Based on the Gleason score, PSA levels, and imaging results, a cancer case is assigned a stage 1 to 4. Higher stage signifies a more advanced, more dangerous disease. Prostate cancer is different from all other common cancers in that as many as three out of four patients have more than one primary cancer focus.[3] The different tumor foci have different properties, including sets of somatic mutations, which complicates the diagnostics and prognostication of the disease.[4]

Most prostate tumors remain small and cause no health problems. These are managed with active surveillance, monitoring the tumor with regular tests to ensure it has not grown. Tumors more likely to be dangerous can be destroyed with radiation therapy or surgically removed by radical prostatectomy. Those whose cancer returns or has already spread beyond the prostate, are treated with hormone therapy that reduces levels of the androgens (male sex hormones) that prostate cells need in order to survive. This halts tumor growth for a while, but eventually cancer cells grow resistant to this treatment. This most-advanced stage of the disease, called castration-resistant prostate cancer, is treated with continued hormone therapy alongside the chemotherapy drug docetaxel. Prostate cancer prognosis depends on how far the cancer has spread at diagnosis and on particular biological properties of the cancer cells. Most men are diagnosed with tumors confined to the prostate; 99% of them survive more than 10 years from their diagnoses. Tumors that have metastasized to distant body sites are most dangerous, with five-year survival rates of 30–40%.

The risk of developing prostate cancer increases with age; the average age of diagnosis is 67. Those with a family history of prostate cancer are more likely to have prostate cancer themselves. Each year 1.2 million cases of prostate cancer are diagnosed, and 350,000 die of the disease,[2] making it the second-leading cause of cancer and cancer death in men. One in eight men is diagnosed with prostate cancer in his lifetime, while one in forty dies of the disease.[5] Prostate tumors were initially thought to be rare, with an 1893 report describing just 50 cases in the medical literature. As surgery became more common, prostate tumors were found in surgical specimens from enlarged prostates. Surgery and radiation therapy methods to treat the disease were developed over the course of the 20th century. Major work describing prostate tumors' need for male sex hormones, and the subsequent development of hormone therapies for prostate cancer, earned Charles B. Huggins the 1966 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and Andrzej W. Schally the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Signs and symptoms

Most cases of prostate cancer are diagnosed through screening tests, when tumors are too small to cause any symptoms.[6] As a tumor grows beyond the prostate, it can damage nearby organs causing erectile dysfunction, blood in the urine or semen, or trouble urinating – often frequent urination and slow or weak urine stream.[6] More than half of men over age 50 experience some form of urination problem,[7] typically due to issues other than prostate cancer such as benign prostatic hyperplasia (non-cancerous enlargement of the prostate).[6]

Advanced prostate tumors often metastasize to nearby bones of the pelvis and back; there they can cause fatigue, unexplained weight loss, and back or bone pain that does not improve with rest.[8] Metastases can damage the bones around them, and around a quarter of those with metastatic prostate cancer develop a bone fracture.[9] Growing metastases can also compress the spinal cord causing weakness in the legs and feet, or limb paralysis.[10][11]

Screening

Prostate cancer screening searches for tumors in those without symptoms. Screening aims to separate men with high-risk cancers who would benefit from treatment, from those whose tumors are slow-growing and unlikely to impact health.[12] This is typically done through blood tests for levels of the protein prostate-specific antigen (PSA), which are elevated in those with enlarged prostates, whether due to prostate cancer or benign prostatic hyperplasia.[13][12][14] The average person's blood has around 1 nanogram (ng) of PSA per milliliter (mL) of blood tested.[15] Those with PSA levels below average are very unlikely to develop dangerous prostate cancer over the next 8 to 10 years.[15] Men with PSA above 3 ng/mL are at increased risk; 30% will have prostate cancer, and 10% a high-grade cancer that requires treatment.[16] Those with PSA levels above 4 ng/mL are often referred for a prostate biopsy; however, even for this high risk group the majority of biopsies are negative for prostate cancer.[17] Men with higher than average PSA levels are often recommended to repeat the blood test four to six weeks later, as PSA levels can fluctuate unrelated to prostate cancer.[18] Those with elevated PSA may undergo secondary screening blood tests that measure subtypes of PSA and other blood proteins to better predict the likelihood that a person will develop aggressive prostate cancer; 4Kscore, Prostate Health Index, ExoDx Prostate Test, and SelectMDx are all available for this purpose.[19]

Several large studies have found that men screened for prostate cancer have a reduced risk of dying from the disease;[20] however, detection of cancer cases that would not have otherwise impacted health can cause anxiety, and lead to unneeded biopsies and treatments.[12] Major national health organizations offer differing recommendations, attempting to balance the benefits of early diagnosis with the potential harms of treating people whose tumors are unlikely to impact health.[12] Most medical guidelines recommend that men in good health and at high risk of prostate cancer (due to age, family history, ethnicity, or prior evidence of high blood PSA levels) be counseled on the risks and benefits of PSA testing, and be offered access to screening tests.[12] Uptake of screening varies by geography – more than 80% of men are screened in the US and Western Europe, 20% of men in Japan, and screening is rare in regions with low human development index.[20]

Diagnosis

Men suspected of having prostate cancer may undergo several tests to help assess the prostate. One common procedure is the digital rectal examination, in which a doctor inserts a lubricated finger into the rectum to feel the nearby prostate.[21][22] Tumors feel like stiff, irregularly shaped lumps against the rest of the prostate. Hardening of the prostate can also be due to benign prostatic hyperplasia; around 20–25% of those with abnormal findings on their rectal exams have prostate cancer.[23]

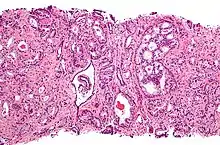

A diagnosis of prostate cancer requires a biopsy of the prostate. Prostate biopsies are typically taken by a needle passing through the rectum or perineum, guided by transrectal ultrasound imaging, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or a combination of the two.[24][22] Ten to twelve samples are taken from several regions of the prostate to improve the chances of finding any tumors.[22] Biopsies are examined under a microscope by a pathologist, who determines the type and extent of cancerous cells present. Cancers are first classified based on their appearance under a microscope. Over 95% of prostate cancers are classified as adenocarcinomas (resembling gland tissue), with the rest largely squamous-cell carcinoma (resembling squamous cells, a type of epithelial cell) and transitional cell carcinoma (resembling transitional cells).[25]

Next tumor samples are graded based on how much the tumor tissue differs from normal prostate tissue; the more different the tumor appears, the faster the tumor is likely to grow. The Gleason grading system is commonly used, where the pathologist assigns a number from 1 (similar to prostate tissue) to 5 (least similar) for the most common pattern observed under the microscope, then does the same for the second-most common pattern. The sum of these two numbers is the Gleason score.[25] The total scores of 2 through 5 are no longer commonly used in practice, making the lowest score 6, and the highest score 10. Scores are commonly grouped into Gleason grade groups: a score of 6 or lower is Gleason grade group 1; a score of 7 with the first number (from the most common pattern) 3 and the second number 4 is grade group 2; the reverse – first number 4, second number 3 – is grade group 3; a score of 8 is grade group 4; a score of 9 or 10 is grade group 5.[25] Higher Gleason scores and higher grade groups represent cancer cases likely to be more aggressive with worse prognosis.[25]

Extent of cancer spread is assessed by MRI or PSMA scan – a positron emission tomography (PET) imaging technique where a radioactive label that binds the prostate protein prostate-specific membrane antigen is used to detect metastases distant from the prostate.[26][22] CT scans may also be used, but are less able to detect spread outside the prostate than MRI. Bone scintigraphy is used to test for spread of cancer to bones.[26]

Staging

After diagnosis, the tumor is staged to determine the extent of its growth and spread. Prostate cancer is typically staged using the American Joint Committee on Cancer's (AJCC) three-component TNM system, with scores assigned for the extent of the tumor (T), spread to any lymph nodes (N), and the presence of metastases (M).[27] Scores of T1 and T2 represent tumors that remain within the prostate: T1 is for tumors not detectable by imaging or digital rectal exam; T2 is for tumors detectable by imaging or rectal exam, but still confined within the prostate.[28] T3 is for tumors that grow beyond the prostate – T3a for tumors with any extension outside the prostate; T3b for tumors that invade the adjacent seminal vesicles. T4 is for tumors that have grown into organs beyond the seminal vesicles.[28] The N and M scores are binary (yes or no). N1 represents any spread to the nearby lymph nodes. M1 represents any metastases to other body sites.[28]

The AJCC then combines the TNM scores, Gleason grade group, and results of the PSA blood test to categorize cancer cases into one of four stages, and their subdivisions. Cancer cases with localized tumors (T1 or T2), no spread (N0 and M0), Gleason grade group 1, and PSA less than 10 ng/mL are designated stage I. Those with localized tumors and PSA between 10 and 20 ng/mL are desigated stage II – subdivided into IIA for Gleason grade group 1, IIB for grade group 2, and IIC for grade group 3 or 4. Stage III is the designation for any of three higher risk factors: IIIA is for a PSA level about 20 ng/mL; IIIB is for T3 or T4 tumors; IIIC is for a Gleason grade group of 5. Stage IV is for cancers that have spread to lymph nodes (N1, stage IVA) or other organs (M1, stage IVB).[27]

| AJCC Stage | TNM scores | Gleason grade group | PSA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | T1 or T2, N0, M0 | 1 | <10 ng/mL |

| Stage IIA | T1 or T2, N0, M0 | 1 | 10-20 ng/mL |

| Stage IIB | 2 | ||

| Stage IIC | 3 or 4 | ||

| Stage IIIA | T1 or T2, N0, M0 | 3 or 4 | > 20 ng/mL |

| Stage IIIB | T3 or T3, N0, M0 | 10-20 ng/mL | |

| Stage IIIC | T1 or T2, N0, M0 | 5 | |

| Stage IVA | Any T, N1 | Any group | Any PSA |

| Stage IVB | Any T, M1 |

The United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends a five-stage system based on disease prognosis called the Cambridge Prognostic Group, with prognostic groups CPG 1 to CPG 5.[29] CPG 1 is the same as AJCC stage I. Cases with localized tumors (T1 or T2) and either Gleason grade group 2 or higher PSA levels (10 to 20 ng/mL) are designated CPG 2. CPG 3 represents either Gleason grade group 3, or the combination of the CPG 2 criteria. CPG 4 is similar to AJCC stage 3 – any of Gleason grade group 4, PSA levels above 20 ng/mL, or a tumor that has grown beyond the prostate (T3). CPG 5 is for the highest risk cases: either a T4 tumor, Gleason grade group 5, or any two of the CPG 4 criteria.[30]

Prevention

No drug or vaccine is approved by regulatory agencies for the prevention of prostate cancer. Several studies have shown 5α-reductase inhibitors to reduce the incidence of prostate cancer; however, whether they reduce disease is not clear.[31]

Management

Treatment of prostate cancer varies based on how advanced the cancer is, the risk it may spread, and the affected person's health and personal preferences.[32] Those with localized disease at low risk for spread are often at greater threat from treatment side effects than disease effects, and so are monitored regularly by active surveillance – repeat testing for a worsening of their disease.[33] Those at higher risk may receive treatment to eliminate the tumor – typically prostatectomy (surgery to remove the prostate) or radiation therapy, sometimes alongside hormone therapy.[34] Those with metastatic disease are additionally treated with chemotherapy, as well as additional radiation or other agents to alleviate the symptoms of metastatic tumors.[34] Throughout the treatment course, blood PSA levels are monitored to assess the effectiveness of treatments, and whether the disease is advancing.[35]

Localized disease

Men diagnosed with low-risk cases of prostate cancer often defer treatment and are instead monitored regularly for cancer progression by active surveillance.[33] Active surveillance involves monitoring the tumor for growth at fixed intervals by PSA tests (around every six months), digital rectal exam (annually), and MRI or repeat biopsies (every one to three years).[33] The goal of active surveillance is to postpone treatment, and avoid overtreatment and its side effects, given a slow-growing or self-limited tumor that in most people is unlikely to cause problems.[36] Various risk-calculating algorithms have been designed that attempt to predict a person with prostate cancer's risk of disease progression based on their clinical characteristics and test results. These include the Partin table and D'Amico risk grouping – which take into account a person's PSA levels, Gleason score, and TNM score – as well as the CAPRA score, which also considers an affected person's age and the percent of their prostate biopsies in which cancerous cells were found.[37] The NICE-endorsed Predict Prostate algorithm and webtool looks at individualized prognosis and benefit from treatment versus conservative management in non-metastatic disease.[38]

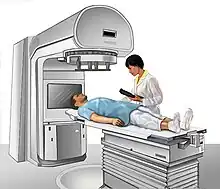

Those who elect to have therapy typically receive radiation therapy or a prostatectomy.[39] Radiation can be delivered by intensity-modulated radiation therapy, which allows for high doses (greater than 80 Gy) to be delivered to the prostate with relatively little radiation to other organs, or by brachytherapy, where a radioactive source is surgically placed next to the prostate.[40][41] Radiotherapy is typically given in several treatments over the course of eight to nine weeks.[42] Radiation damage to nearby organs can increase the risk of subsequent bladder cancer and cause erectile dysfunction, infertility, and gastronintestinal problems: diarrhea, bloody stools, fecal incontinence, and pain.[42] For those with relatively high-risk localized disease, combining radiation with androgen deprivation therapy improves overall survival.[40]

Radical prostatectomy aims to surgically remove the cancerous part of the prostate, along with the seminal vesicles, and parts of the vas deferens.[43] This is typically done by robot-assisted surgery, where robotic tools inserted through small holes in the abdomen allow a surgeon to make small and exact movements during surgery.[44] This method results in shorter hospital stays, less blood loss, and fewer complications than traditional open surgery.[44] In places where robot-assisted surgery is unavailable, prostatectomy can be performed laparoscopically (using a camera and hand tools through small holes in the abdomen), or through traditional open surgery with an incision above the penis (retropubic approach) or below the scrotum (perineal approach).[45][44] The four approaches result in similar rates of cancer control.[45] Damage to nearby tissue during surgery can result in erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence. Erectile dysfunction is more likely in those who are older or had previous erectile issues.[45] Incontinence is more common in those who are older and have shorter urethras.[45] Both for cancer progression outcomes and surgical side effects, the skill and experience of the individual surgeon doing the procedure are among the greatest determinants of success.[45]

Radiotherapy and surgery result in similar outcomes with respect to bowel, erectile and urinary function after five years.[46] Successful radiotherapy causes a drop in PSA levels due to destruction of the tumor, while prostatectomy causes PSA to drop to undetectable levels.[47] After treatment for localized prostate cancer, PSA levels are monitored regularly. Up to half of those treated will eventually have a rise in PSA levels, suggesting the tumor or small metastases are growing again.[48] People with high or rising PSA levels are often offered another round of radiation therapy directed at the former tumor site. This reduces risk for further progression by 75%.[47] Those suspected of metastases can undergo PET scanning with sensitive radiotracers C-11 choline, F-18 fluciclovine, and F-18 or Ga-68 attached to a PSMA-targeting drug, each of which is able to detect small metastases more sensitively than alternative imaging methods.[49][47]

Metastatic disease

For those with metastatic disease, the standard of care is androgen deprivation therapy, drugs that reduce levels of androgens (male sex hormones) that prostate cells require in order to grow.[50] Various drugs are used to lower androgen levels by blocking the synthesis or action of testosterone, the primary androgen. The first line of treatment is typically GnRH agonists like leuprolide, goserelin, triptorelin, or leuprolide mesylate by injection monthly or less frequently if needed.[51][50] GnRH agonists cause a brief rise in testosterone levels at treatment initiation, which can worsen disease in people with significant symptoms of metastases.[52] In these people, GnRH antagonists like degarelix or relugolix are given instead, and can also rapidly reduce testosterone levels.[52] Hormone therapy halts tumor growth in more than 95% of those treated,[53] with PSA levels returning to normal in up to 70%.[54]

Despite reduced testosterone levels, eventually nearly all prostate cancers continue to grow – typically manifested by rising blood PSA levels, and metastases to nearby bones.[55][56] This is the most advanced stage of the disease, called castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). CRPC is typically treated with systemic chemotherapy alongside continued hormone therapy. The standard of care is docetaxel given every three weeks.[57] Most CRPC cases still rely on androgen signaling, and so antiandrogen drugs are often used, namely the androgen receptor antagonists enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide, as well as the testosterone production inhibitor abiraterone acetate.[55][58] Those whose cancer becomes resistant to docetaxel may receive the second-generation taxane drug cabazitaxel.[55] An alternative is the cell therapy procedure Sipuleucel-T, where the affected person's immune cells are removed, treated to more effectively target prostate cancer cells, and re-injected into the same person.[55][58]

Supportive care

Bone metastases – present in around 85% of those with metastatic prostate cancer – are the primary cause of symptoms and death from metastatic prostate cancer.[59][60] Metastases can cause severe pain and bone weakening, with around 25% of those affected developing a bone fracture.[60] Those with constant pain are often prescribed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.[61] However, people with bone metastases often experience "breakthrough pain", sudden bursts of severe pain that resolve within around 15 minutes, before pain medications can take effect.[61] Single sites of pain can be treated with external beam radiation therapy to shrink nearby tumors.[62] More dispersed bone pain can be treated with radioactive compounds that disproportionately accumulate in bone, like radium-223 and samarium-153-EDTMP, which help reduce the size of bone tumors. Similarly, the systemic chemotherapeutics used for metastatic prostate cancer can reduce pain as they shrink tumors.[62] Other bone modifying agents like zoledronic acid and denosumab can reduce prostate cancer bone pain, even though they have little effect on tumor size.[62] Metastases compress the spinal cord in up to 12% of those with metastatic prostate cancer causing pain, weakness, numbness, and paralysis.[63][64] Inflammation in the spine can be treated with high-dose steroids, as well as surgery and radiotherapy to shrink spinal tumors and relieve pressure on the spinal cord.[63][64]

Those with advanced prostate cancer often suffer fatigue, lethargy, and a generalized weakness. This is caused in part by gastrointestinal problems, with loss of appetite, weight loss, nausea, and constipation all common. These are typically treated with appetite-increasing drugs – megestrol acetate or corticosteroids – antiemetics, or treatments that focus on underlying gastrointestinal issues.[65] General weakness can also be caused by anemia, itself caused by a combination of the disease itself, poor nutrition, and damage to the bone marrow from cancer treatments or bone metastases.[66] Anemia can be improved various ways depending on the cause, or can be addressed directly with blood transfusions.[66] Organ damage and metastases in the lymph nodes can lead to uncomfortable accumulation of fluid (called lymphedema) in the genitals or lower limbs. These swellings can be extremely painful, curtailing an affected person's ability to urinate, have sex, or walk normally. Lymphedema can be treated by applying pressure to aid drainage, surgically draining pooled fluid, and cleaning and treating nearby damaged skin.[67]

People with prostate cancer are around twice as likely to experience anxiety or depression compared to those without cancer.[68] When added to normal prostate cancer treatments, psychological interventions such as psychoeducation and cognitive behavioural therapy can help reduce anxiety, depression, and general distress.[69]

As those severely ill with metastatic prostate cancer near the end of their lives, most experience confusion and may hallucinate or have trouble recognizing loved ones.[70][71] Confusion is caused by various conditions, including kidney failure, sepsis, dehydration, and as a side effect of various drugs, especially opioids.[70] Most people sleep for long periods, and some feel drowsy when awake.[71] Restlessness is also common, sometimes caused by physical discomfort from constipation or urinary retention, sometimes caused by anxiety.[71] In their last few days, affected men's breathing may become shallow and slow, with long pauses between breaths. Breathing may be accompanied by a rattling noise as fluid lingers in the throat, but this is not uncomfortable for the affected person.[71][72] Their hands and feet may cool to the touch, and skin become blotchy or blue due to weaker blood circulation. Many stop eating and drinking, resulting in dry-feeling mouth, which can be aided by moistening the mouth and lips.[71] The person becomes less and less responsive, and eventually the heart and breathing stop.[72]

Prognosis

The prognosis of diagnosed prostate cancer varies widely based on the cancer's grade and stage at the time of diagnosis; those with lower stage disease have vastly improved prognoses. Around 80% of prostate cancer diagnoses are in men whose cancer is still confined to the prostate. These men often survive long after diagnosis, with as many as 99% still alive 10 years from diagnosis.[73] Men whose cancer has metastasized to a nearby part of the body (around 15% of diagnoses) have poorer prognoses, with five-year survival rates of 60–80%.[74] Those with metastases in distant body sites (around 5% of diagnoses) have relatively poor prognoses, with five-year survival rates of 30–40%.[74]

Those who have low blood PSA levels at diagnosis, and whose tumors have a low Gleason grade and less-advanced clinical stage tend to have better prognoses.[75] After prostatectomy or radiotherapy, those who have a short time between treatment and a subsequent rise in PSA levels, or a rapid rate of PSA level increases are more likely to die from their cancers.[48] However, the prognostic models are not very accurate, and there is extensive research with aim to develop improved risk classification models.

Castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer is incurable,[76] and kills a majority of those whose disease reaches this stage.[55]

Cause

Prostate cancer is caused by the accumulation of genetic mutations to the DNA of cells in the prostate. These mutations affect genes involved in cell growth, replication, cell death, and DNA damage repair.[77] Changes to these genes can cause cells in the prostate to grow uncontrollably, resulting in a tumor.[78] Over time, the tumor may grow large enough to invade nearby organs such as the seminal vesicles or bladder.[79] Eventually, tumor cells develop the ability to travel through the lymphatic system to nearby lymph nodes, or through the bloodstream to the bone marrow and (more rarely) other body sites.[80] At these new sites, the cancer cells disrupt normal body function and continue to grow. Metastases cause most of the discomfort associated with prostate cancer, and eventually can kill the affected person.[80]

Pathophysiology

Most prostate tumors begin in the peripheral zone – the outermost part of the prostate.[81] As cells begin to grow out of control, they form a small clump of disregulated cells called a prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN).[82] Some PINs continue to grow, forming layers of tissue that stop expressing genes common to their original tissue location – p63, cytokeratin 5, and cytokeratin 14 – and begin expressing genes common to cells that makeup the innermost lining of the pancreatic duct – cytokeratin 8 and cytokeratin 18.[81] These multilayered PINs also often overexpress the gene AMACR, which is associated with prostate cancer progression.[81]

Particularly large PINs can eventually grow into tumors. This is commonly accompanied by large-scale changes to the genome, with chromosome sequences being rearranged or copied repeatedly. Some genomic alterations are partiuclarly common in early prostate cancer, namely gene fusion between TMPRSS2 and the oncogene ERG (up to 60% of prostate tumors), mutations that disable SPOP (up to 15% of tumors), and mutations that hyperactivate FOXA1 (up to 5% of tumors).[81]

Metastatic prostate cancer tends to have more genetic mutations than localized disease.[83] Many of these mutations are in genes that protect from DNA damage, such as p53 (mutated in 8% of localized tumors, more than 27% of metastatic ones) and RB1 (1% of localized tumors, more than 5% of metastatic ones).[83] Similarly mutations in the DNA repair-related genes BRCA2 and ATM are rare in localized disease but found in at least 7% and 5% of metastatic disease cases respectively.[83]

The transition from castrate-sensitive to castrate-resistant prostate cancer is also accompanied by the acquisition of various gene mutations. In castrate-resistant disease, more than 70% of tumors have mutations in the androgen receptor signaling pathway – amplifications and gain-of-function mutations in the receptor gene itself, amplification of its activators (e.g. FOXA1), or inactivating mutations in its negative regulators (e.g. ZBTB16 and NCOR1).[83] These androgen receptor disruptions are only found in up to 6% of biopsies of castrate-sensitive metastatic disease.[83] Similarly, deletions of the tumor suppressor PTEN are harbored by 12–17% of castrate-sensitive tumors, but over 40% of castrate-resistant tumors.[83] Less commonly, tumors have aberrant activation of the Wnt signaling pathway via disruption of members APC (9% of tumors) or CTNNB1 (4% of tumors); dysregulation of the PI3K pathway via PI3KCA/PI3KCB mutations (6% of tumors) or AKT1 (2% of tumors).[83]

Epidemiology

Prostate cancer is the second-most frequently diagnosed cancer in men, and the second-most frequent cause of cancer death in men (after lung cancer).[2][5] Around 1.2 million new cases of prostate cancer are diagnosed each year, and 350,000 men die of the disease.[2] One in eight men are diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime, and around one in forty die of the disease.[5] Rates of prostate cancer rise with age. Due to this, prostate cancer rates are generally higher in parts of the world with higher life expectancy, which also tend to be areas with higher gross domestic product and higher human development index.[2] Australia, Europe, North America, New Zealand, and parts of South America have the highest incidence. South Asia, Central Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa have the lowest incidence of prostate cancer; though incidence is increasing in these regions at among the fastest rates in the world.[2] Prostate cancer is the most diagnosed cancer in men in over half of the world's countries, and the leading cause of cancer death in men in around a quarter of countries.[85]

Prostate cancer is rare in those under 40 years old.[86] The overwhelming majority of cases are diagnosed in those over 60 years,[2] with the average person diagnosed at 67.[87] The average person who dies from prostate cancer is 77.[87] Only a minority of prostate cancer cases are ever diagnosed. Autopsies of men who died at various ages have shown cancer in the prostates of over 40% of men over age 50. Incidence rises with age, and nearly 70% of men autopsied at age 80–89 had cancer in their prostates.[88]

Genetics

Prostate cancer is more common in some families. Men with an affected first-degree relative (father or brother) have more than twice the risk of developing prostate cancer, and those with two first-degree relatives have a five-fold greater risk compared with men with no family history.[89] Increased risk also runs in some ethnic groups, with men of African and African-Caribbean ancestry at particularly high risk – having prostate cancer at higher rates, and having more-aggressive prostate cancers that develop at earlier ages.[90] Large genome-wide association studies have identified over 100 gene variants associated with increased prostate cancer risk.[91] The greatest risk increase is associated with variations in BRCA2 (up to an eight-fold increased risk) and HOXB13 (three-fold increased risk), both of which are involved in repairing DNA damage.[91] Variants in other genes involved in DNA damage repair have also been associated with an increased risk of developing prostate cancer – particularly early-onset prostate cancer – including BRCA1, ATM, NBS1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, CHEK2, RAD51D, and PALB2.[91] Additionally, variants in the genome near the oncogene MYC are associated with increased risk.[91] As are single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor common in African-Americans, and in the androgen receptor, CYP3A4, and CYP17 involved in testosterone synthesis and signaling.[89] Together known gene variants are estimated to cause around 25% of prostate cancer cases, including 40% of early-onset prostate cancers.[89] It is noteworthy that the somatic mutations found in one cancer focus are completely divergent from those detected in another focus of the same patient.[92]

Body and lifestyle

Men who are taller are at a slightly increased risk for developing prostate cancer, as are men who are obese.[93] High levels of blood cholesterol are also associated with increased prostate cancer risk; consequently, those who take the cholesterol-lowering drugs, statins, have a reduced risk of advanced prostate cancer.[94] Chronic inflammation can cause various cancers. Potential links between infection (or other sources of inflammation) and prostate cancer have been studied but none definitively found, with one large study finding no link between prostate cancer and a history of gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, or infection with various human papillomaviruses.[95]

Regular vigorous exercise may reduce one's chance of developing advanced prostate cancer, as can several dietary interventions.[96] Those with a diet rich in cruciferous vegetables, fish, genistein, or lycopene (found in tomatoes) are at a reduced risk of symptomatic prostate cancer.[89][97] Conversely, those who consume high levels of dietary fats, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (from cooking red meats), or calcium may be at an increased risk of developing advanced prostate cancer.[89][98] Several dietary supplements have been studied and found not to impact prostate cancer risk, including selenium, vitamin C, vitamin D, and vitamin E.[31][98]

History

A tumor in the prostate was first described in 1817 by the English surgeon George Langstaff, following the autopsy of a man who had died at age 68 with lower-body pain and urinary issues.[99][100] In 1853, London Hospital surgeon John Adams described another prostate tumor from a man who had died with urinary issues; Adams had a pathologist examine the tumor, providing the first histologically confirmed case of a cancerous tumor in the prostate.[99][101] The disease was initially thought to be uncommon as it was rarely distinguished from other causes of urinary obstruction.[102] An 1893 report found only 50 cases described in the medical literature.[103] Around the turn of the 19th century, prostate surgery to relieve urinary obstruction became more common, allowing surgeons and pathologists to examine the removed prostate tissue. Two studies around the time found cancer in as many as 10% of surgical specimens, suggesting prostate cancer was a fairly common cause of prostate enlargement.[103]

For much of the 20th century, the primary therapy for prostate cancer was surgery to remove the prostate. Perineal prostatectomy was first performed in 1904 by Hugh H. Young at Johns Hopkins Hospital.[104][105] Young's method became the widespread standard, initially done primarily to relieve symptoms of urinary blockage.[104] In 1931 a new surgical method, transurethral resection of the prostate, became available, replacing perineal prostatectomy for symptomatic relief of obstruction.[103] In 1945, Terence Millin described a retropubic prostatectomy approach, which provided easier access to pelvic lymph nodes to assist in staging the extent of disease, and was easier for surgeons to learn.[104] This was improved upon by Patrick C. Walsh's 1983 description of a retropubic prostatectomy approach that avoided damage to the nerves near the prostate, preserving erectile function.[104][106]

Radiation therapy for prostate cancer was used occasionally in the early 20th century, with radium implanted into the urethra or rectum to reduce the tumor size and associated symptoms.[107] In the 1950s the advent of more powerful radiation machines allowed for external beam radiotherapy to reach the prostate. By the 1960s, this was often combined with hormone therapy to improve the potency of therapy.[107] In the 1970s, Willet Whitmore pioneered an open surgery technique where needles of Iodine-125 were placed directly into the prostate. This was improved upon by Henrik H. Holm in 1983 by using transcrectal ultrasound to guide the implantation of radioactive material.[107]

The observation that the testicles (and the hormones they secrete) influence prostate size was made as early as the late 18th century via castration experiments in animals. However, occasional experimentation over the next century bore mixed results, likely due to the inability to separate prostate tumors from prostates enlarged due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. In 1941, Charles B. Huggins and Clarence V. Hodges published two studies using surgical castration or oral estrogen to reduce androgen levels and improve prostate cancer symptoms. Huggins was awarded the 1966 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this discovery, the first systemic therapy for prostate cancer.[108][109] In the 1960s, large studies showed estrogen therapy to be as effective as surgical castration at treating prostate cancer, but that those on estrogen therapy were at increased risk of suffering blood clots.[108] Through the 1980s, Andrzej W. Schally's studies of GnRH led to the development of GnRH agonists, which were found to be as effective as estrogen without the increased risk of clotting.[108][110] Schally was awarded the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on GnRH and prostate cancer.[108]

Systemic chemotherapy for prostate cancer has been studied since the 1950s, with clinical trials failing to show benefits in most people who receive the drug.[111] In 1996, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the systemic chemotherapy mitoxantrone for those with castration-resistant prostate cancer based on trials showing that it improved symptoms even though it failed to enhance survival.[112] In 2004, docetaxel was approved as the first chemotherapy to increase survival in those with castration-resistant prostate cancer.[112] After additional trials in 2015, docetaxel use was extended to those with castration-sensitive prostate cancer.[113]

Society and culture

Prostate cancer screening and awareness have been widely promoted since the early 2000s by Prostate Cancer Awareness Month in September and Movember in November.[114] Analyses of internet searches and social media posts suggest neither event changes the level of prostate cancer interest or discussion, in contrast to the more established Breast Cancer Awareness Month.[114][115] A light blue ribbon is used to promote prostate cancer awareness.

Research

Prostate cancer is a major topic of ongoing research, with the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI, the world's largest funder of cancer research) spending $209 million on prostate cancer research in 2020 – the sixth highest among cancer types.[116] Despite high gross spending, prostate cancer research funding is relatively low for the number of deaths it causes. The NCI spends around $5,700 per prostate cancer death, considerably lower than for brain cancer ($21,000 per death), breast cancer ($13,000 per death) or cancer as a whole ($11,000 per death).[117] A similar trend holds for private nonprofit organizations. Annual revenues of prostate cancer-focused nonprofits rank sixth among cancer types, but prostate cancer nonprofits have lower revenue than would be expected for the number of cases, deaths, and potential years of life lost.[118]

Research into prostate cancer relies on a number of laboratory models to test aspects of the disease. Several prostate immortalized cell lines are widely used, namely the classic lines DU145, PC-3, and LNCaP, as well as more recent cell lines 22Rv1, LAPC-4, VCaP, and MDA-PCa-2a and −2b.[119] Research requiring more complex models of the prostate uses organoids – clusters of prostate cells that can be grown from human prostate tumors or stem cells.[120] Modeling tumor growth and metastasis requires a model organism, typically a mouse. Researchers can either surgically implant human prostate tumors into immunocompromised mice (a technique called a patient derived xenograft),[121] or can induce prostate tumors in mice either with chemical exposure or genetic engineering.[122] These genetically engineered mouse models typically use a Cre recombinase system to disrupt tumor suppressors or activate oncogenes specifically in prostate cells.[123]

References

- "Survival Rates for Prostate Cancer". American Cancer Society. 1 March 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Epidemiology".

- Andreoiu & Cheng 2010, "Epidemiology".

- Løvf et al. 2019, "Epidemiology".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Prostate Cancer".

- "Prostate Cancer Signs and Symptoms". American Cancer Society. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- Merriel, Funston & Hamilton 2018, "Symptoms and Signs".

- "Symptoms of Prostate Cancer". Cancer Research UK. 15 March 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- Coleman et al. 2020, "Prostate cancer".

- Clinical Overview 2022, "Clinical Presentation".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Metastatic Disease: Noncastrate".

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Screening and early detection".

- Dall'Era 2023, "Serum tumor markers".

- "What Is Screening for Prostate Cancer". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 25 August 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- Carlsson & Vickers 2020, "3. Tailor screening frequency based on PSA-level".

- Carlsson & Vickers 2020, "5. Use secondary tests such as marker or imaging before biopsy.".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Prostate-Specific Antigen".

- Carlsson & Vickers 2020, "4. For men with elevated PSA (≥3 ng/mL), repeat PSA.".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Second-Line Screening Tests".

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Box 1: Screening for prostate cancer in different regions".

- "Tests to Diagnose and Stage Prostate Cancer". American Cancer Society. 21 February 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Diagnosis".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Physical Examination".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Prostate Biopsy".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Pathology".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Prostate Cancer Staging".

- "Prostate Cancer Staging". American Cancer Society. 8 October 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Table 87-1 TNM Classification".

- "Prostate cancer: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [NG131]". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 9 May 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- "Prostate cancer risk groups and the Cambridge Prognostic Group (CPG)". Cancer Research UK. 24 May 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "No Cancer Diagnosis".

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Management".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Active surveillance".

- "Initial Treatment of Prostate Cancer, by Stage and Risk Group". American Cancer Society. 9 August 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- "Following PSA Levels During and After Prostate Cancer Treatment". American Cancer Society. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- Ellis SD, Hwang S, Morrow E, Kimminau KS, Goonan K, Petty L, et al. (May 2021). "Perceived barriers to the adoption of active surveillance in low-risk prostate cancer: a qualitative analysis of community and academic urologists". BMC Cancer. 21 (1): 649. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-08386-3. PMC 8165996. PMID 34058998.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Rebello et al. 2021, "Table 1: Prostate cancer risk classification at diagnosis and after treatment".

- Thurtle DR, Greenberg DC, Lee LS, Huang HH, Pharoah PD, Gnanapragasam VJ (March 2019). "Individual prognosis at diagnosis in nonmetastatic prostate cancer: Development and external validation of the PREDICT Prostate multivariable model". PLOS Medicine. 16 (3): e1002758. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002758. PMC 6413892. PMID 30860997.

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "External Beam Radiation Therapy".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Brachytherapy".

- Brawley, Mohan & Nein 2018, "Radiation Therapy".

- Dall'Era 2023, "Radical Prostatectomy".

- Costello 2020, "The rise of robotic surgery".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Radical prostatectomy".

- Wallis CJ, Glaser A, Hu JC, Huland H, Lawrentschuk N, Moon D, et al. (January 2018). "Survival and Complications Following Surgery and Radiation for Localized Prostate Cancer: An International Collaborative Review" (PDF). European Urology. 73 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2017.05.055. PMID 28610779.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Rebello et al. 2021, "Biocehmical recurrence and residual disease".

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Biochemical recurrence and residual disease".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Rising PSA After Definitive Local Therapy".

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer".

- "Hormone Therapy for Prostate Cancer". American Cancer Society. 9 August 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Testosterone-Lowering Agents".

- Achard et al. 2022, "Introduction".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Outcomes of Androgen Deprivation".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Metastatic Disease:Castrate".

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer".

- Teo, Rathkopf & Kantoff 2019, "Management of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer".

- Teo, Rathkopf & Kantoff 2019, "Abiraterone Acetate".

- Coleman et al. 2020, "Prevalence of bone metastases".

- Coleman et al. 2020, "Prevalence of SREs".

- Coleman et al. 2020, "Analgesics used in CIBP".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Pain Management".

- Thompson, Wood & Feuer 2007, "Cord compression".

- "What is metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC)". Prostate Cancer UK. June 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- Thompson, Wood & Feuer 2007, "Gastrointestinal symptoms".

- Thompson, Wood & Feuer 2007, "General debility".

- Thompson, Wood & Feuer 2007, "Lymphoedema".

- Mundle, Afenya & Agarwal 2021, "Estimates of anxiety, depression, and distress".

- Mundle, Afenya & Agarwal 2021, "Abstract".

- Thompson, Wood & Feuer 2007, "Delirium".

- "Dying from prostate cancer – What to expect". Prostate Cancer UK. July 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- "Care Through the Final Days". American Society of Clinical Oncology. November 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Prognosis and survival".

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Figure 3: Prostate cancer stages and progression.".

- Pilié et al. 2022, "Table 45-2".

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Abstract".

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Genetics".

- "What Causes Prostate Cancer?". American Cancer Society. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- "Locally advanced prostate cancer". Cancer Research UK. 31 May 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Disease progression".

- Sandhu et al. 2021, "The biology of prostate cancer".

- "Understanding Your Pathology Report: Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia (PIN) and Intraductal Carcinoma". American Cancer Society. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Metastatic disease".

- "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- Bergengren et al. 2023, "3.1 Epidemiology".

- Pernar et al. 2018, "Risk Factors for Total Prostate Cancer".

- Stephenson, Abouassaly & Klein 2021, "Age at Diagnosis".

- Dall'Era 2023, "General Considerations".

- Scher & Eastham 2022, "Epidemiology".

- McHugh et al. 2022, "Introduction".

- Rebello et al. 2021, "Genetic Predisposition".

- Løvf et al. 2019, "Genetics".

- Pernar et al. 2018, "Risk Factors for Advanced and Fatal Prostate Cancer".

- Pernar et al. 2018, "Statins".

- Stephenson, Abouassaly & Klein 2021, "Inflammation and Infection".

- Pernar et al. 2018, "Exercise".

- Pernar et al. 2018, "Fish".

- Pernar et al. 2018, "Calcium, Dairy Products, and Vitamin D".

- Valier 2016, pp. 15–18.

- Lawrence W (1817). "Cases of Fungus Hæmatodes, with Observations, by George Langstaff, Esq. and an Appendix, containing two cases of Analogous Affections". Med Chir Trans. 8: 272–314. doi:10.1177/095952871700800114. PMC 2129005. PMID 20895322.

- Adams J (1853). "The case of scirrhous of the prostate gland with corresponding affliction of the lymphatic glands in the lumbar region and in the pelvis". Lancet. 1 (1547): 393–94. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)68759-8.

- Denmeade & Isaacs 2002, "Main".

- Lytton 2001, p. 1859.

- Denmeade & Isaacs 2002, "Prostatectomy".

- Young HH (1905). "Four cases of radical prostatectomy". Johns Hopkins Bull. 16.

- Walsh PC, Lepor H, Eggleston JC (1983). "Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations". The Prostate. 4 (5): 473–485. doi:10.1002/pros.2990040506. PMID 6889192. S2CID 30740301.

- Denmeade & Isaacs 2002, "Radiation therapy".

- Denmeade & Isaacs 2002, "Androgen-ablation therapy".

- Huggins CB, Hodges CV (1941). "Studies on prostate cancer: 1. The effects of castration, of estrogen and androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate". Cancer Res. 1 (4): 293. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- Tolis G, Ackman D, Stellos A, Mehta A, Labrie F, Fazekas AT, et al. (March 1982). "Tumor growth inhibition in patients with prostatic carcinoma treated with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 79 (5): 1658–1662. Bibcode:1982PNAS...79.1658T. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.5.1658. PMC 346035. PMID 6461861.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Denmeade & Isaacs 2002, "Cytotoxic chemotherapy".

- Desai, McManus & Sharifi 2021, "Evolution of Treatment".

- Teo, Rathkopf & Kantoff 2019, "Figure 1".

- Patel et al. 2020, p. 64.

- Johnson et al. 2021, "Abstract".

- "Funding for Research Areas". National Cancer Institute. 10 May 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- "Estimates of Funding for Various Research, Condition, and Disease Categories (RCDC)". US National Institutes of Health. 31 March 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- Kamath, Kircher & Benson 2019, "Results".

- Mai et al. 2022, 2.1 Human prostate cancer cell lines.

- Mai et al. 2022, 2.4. Organoids.

- Mai et al. 2022, 2.2 PDX lines.

- Mai et al. 2022, 2.3 Genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM).

- Ittmann et al. 2013, "Introduction".

Works cited

- Achard V, Putora PM, Omlin A, Zilli T, Fischer S (2022). "Metastatic Prostate Cancer: Treatment Options". Oncology. 100 (1): 48–59. doi:10.1159/000519861. PMID 34781285. S2CID 244132770.

- Andreoiu M, Cheng L (2010). "Multifocal prostate cancer: biologic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications". Hum Pathol. 41: 781–793. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2010.02.011. PMID 20466122.

- Løvf M, Zhao S, Axcrona U, Johannessen B, Bakken AC, Carm KT, et al. (2019). "Multifocal primary prostate cancer exhibits high degree of genomic heterogeneity". Eur Urol. 75 (3): 498–505. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2018.08.009. PMID 30181068.

- Bergengren O, Pekala KR, Matsoukas K, Fainberg J, Mungovan SF, Bratt O, et al. (May 2023). "2022 Update on Prostate Cancer Epidemiology and Risk Factors-A Systematic Review". Eur Urol. 84 (2): 191–206. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2023.04.021. PMID 37202314. S2CID 258780321.

- Brawley S, Mohan R, Nein CD (June 2018). "Localized Prostate Cancer: Treatment Options". American Family Physician. 97 (12): 798–805. PMID 30216009.

- Carlsson SV, Vickers AJ (November 2020). "Screening for Prostate Cancer". Med Clin North Am. 104 (6): 1051–1062. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2020.08.007. PMC 8287565. PMID 33099450.

- Coleman RE, Croucher PI, Padhani AR, Clézardin P, Chow E, Fallon M, et al. (October 2020). "Bone metastases". Nat Rev Dis Primers. 6 (1): 83. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-00216-3. hdl:20.500.11820/6bac9e59-0afa-4b4a-bebf-4e747b889917. PMID 33060614. S2CID 222350837.

- Costello AJ (March 2020). "Considering the role of radical prostatectomy in 21st century prostate cancer care". Nat Rev Urol. 17 (3): 177–188. doi:10.1038/s41585-020-0287-y. PMID 32086498.

- Dall'Era MA (2023). "39-17: Prostate Cancer". In Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ, Rabow MW, McQuaid KR (eds.). Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment 2023 (62 ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-1-2646-8734-3.

- Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT (May 2002). "A history of prostate cancer treatment". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2 (5): 389–396. doi:10.1038/nrc801. PMC 4124639. PMID 12044015.

- Desai K, McManus JM, Sharifi N (May 2021). "Hormonal Therapy for Prostate Cancer". Endocr Rev. 42 (3): 354–373. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnab002. PMC 8152444. PMID 33480983.

- Hessen MT, ed. (August 2022). "Prostate Cancer". Clinical Overviews. Point of Care. Elsevier.

- Ittmann M, Huang J, Radaelli E, Martin P, Signoretti S, Sullivan R, et al. (May 2013). "Animal models of human prostate cancer: the consensus report of the New York meeting of the Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium Prostate Pathology Committee". Cancer Res. 73 (9): 2718–36. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4213. PMC 3644021. PMID 23610450.

- Johnson BS, Shepard S, Torgeson T, Johnson A, McMurray M, Vassar M (February 2021). "Using Google Trends and Twitter for Prostate Cancer Awareness: A Comparative Analysis of Prostate Cancer Awareness Month and Breast Cancer Awareness Month". Cureus. 13 (2): e13325. doi:10.7759/cureus.13325. PMC 7958554. PMID 33738168.

- Kamath SD, Kircher SM, Benson AB (July 2019). "Comparison of Cancer Burden and Nonprofit Organization Funding Reveals Disparities in Funding Across Cancer Types". J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 17 (7): 849–854. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2018.7280. PMID 31319386. S2CID 197666475.

- Loeb S, Eastham JA (2021). "Diagnosis and Staging of Prostate Cancer". In Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA (eds.). Cambell-Walsh-Wein Urology (12 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-54642-3.

- Lytton B (June 2001). "Prostate cancer: a brief history and the discovery of hormonal ablation treatment". The Journal of Urology. 165 (6 Pt 1): 1859–1862. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66228-3. PMID 11371867.

- Mai CW, Chin KY, Foong LC, Pang KL, Yu B, Shu Y, et al. (September 2022). "Modeling prostate cancer: What does it take to build an ideal tumor model?". Cancer Lett. 543: 215794. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215794. PMID 35718268. S2CID 249831438.

- McHugh J, Saunders EJ, Dadaev T, McGrowder E, Bancroft E, Kote-Jarai Z, et al. (June 2022). "Prostate cancer risk in men of differing genetic ancestry and approaches to disease screening and management in these groups". Br J Cancer. 126 (10): 1366–1373. doi:10.1038/s41416-021-01669-3. PMC 9090767. PMID 34923574.

- Merriel SW, Funston G, Hamilton W (September 2018). "Prostate Cancer in Primary Care". Adv Ther. 35 (9): 1285–1294. doi:10.1007/s12325-018-0766-1. PMC 6133140. PMID 30097885.

- Mundle R, Afenya E, Agarwal N (September 2021). "The effectiveness of psychological intervention for depression, anxiety, and distress in prostate cancer: a systematic review of literature". Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 24 (3): 674–687. doi:10.1038/s41391-021-00342-3. PMID 33750905. S2CID 232325496.

- Patel MS, Halpern JA, Desai AS, Keeter MK, Bennett NE, Brannigan RE (May 2020). "Success of Prostate and Testicular Cancer Awareness Campaigns Compared to Breast Cancer Awareness Month According to Internet Search Volumes: A Google Trends Analysis". Urology. 139: 64–70. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2019.11.062. PMID 32001306. S2CID 210982209.

- Pernar CH, Ebot EM, Wilson KM, Mucci LA (December 2018). "The Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer". Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 8 (12): a030361. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a030361. PMC 6280714. PMID 29311132.

- Pilié P, Viscuse P, Logothetis CJ, Corn PG (2022). "45: Prostate Cancer". In Kantarjian HM, Wolff RA, Rieber AG (eds.). The MD Anderson Manual of Medical Oncology (4 ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-1-260-46764-2.

- Rebello RJ, Oing C, Knudsen KE, Loeb S, Johnson DC, Reiter RE, et al. (February 2021). "Prostate cancer". Nat Rev Dis Primers. 7 (1): 9. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-00243-0. PMID 33542230. S2CID 231794303.

- Scher HI, Eastham JA (2022). "87: Benign and Malignant Diseases of the Prostate". In Loscalzo J, Fauci A, Kasper D, et al. (eds.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (21 ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-1-264-26850-4.

- Stephenson AJ, Abouassaly R, Klein EA (2021). "Epidemiology, Etiology, and Prevention of Prostate Cancer". In Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA (eds.). Cambell-Walsh-Wein Urology (12 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-54642-3.

- Sandhu S, Moore CM, Chiong E, Beltran H, Bristow RG, Williams SG (September 2021). "Prostate cancer". Lancet. 398 (10305): 1075–1090. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00950-8. PMID 34370973. S2CID 236941733.

- Teo MY, Rathkopf DE, Kantoff P (January 2019). "Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer". Annu Rev Med. 70: 479–499. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-051517-011947. PMC 6441973. PMID 30691365.

- Thompson JC, Wood J, Feuer D (2007). "Prostate cancer: palliative care and pain relief". Br Med Bull. 83: 341–354. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldm018. PMID 17628024.

- Valier H (2016). "The Problematic Prehistory of Prostate Cancer". A History of Prostate Cancer. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-1-4039-8803-4.