Benin Expedition of 1897

The Benin Expedition of 1897 was a punitive expedition by a British force of 1,200 men under Sir Harry Rawson in response to the ambush of a previous British embassy under Acting Consul General James Phillips, of the Niger Coast Protectorate.[1] Rawson's troops captured and sacked Benin City, bringing to an end the Kingdom of Benin, which was eventually absorbed into colonial Nigeria.[1]

| Benin Expedition of 1897 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Scramble for Africa | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,200 | Unknown | ||||||

The Expedition freed some people held as slaves by the king.[2]

Background

At the end of the 19th century, the Kingdom of Benin had managed to retain its independence during the Scramble for Africa, and the Oba of Benin exercised a monopoly over trade in Benin's territories which the Royal Niger Company considered a threat. In 1892, Deputy Commissioner and Vice-Consul Captain Henry Lionel Galway (1859–1949) tried to negotiate a trade agreement with Oba Ovọnramwẹn Nọgbaisi (1888–1914) to allow for the free passage of goods through his territory and the development of the palm oil industry. Captain Gallwey (as his name was then spelled) would push for British interests in the region, especially of the palm oil industry, by attempting to negotiate a free trade agreement with the Oba at the time. Later on, Moor would urge the Foreign office to use whatever means to secure the signed treaty, up to and including force.[3] Gallwey signed the treaty with the Oba and his chiefs which gave Britain legal justification for exerting greater influence in the region. While the treaty itself contained clauses which suggested that the Oba had sought British protection, this was not corroborated by either him or Gallwey. According to Gallwey's own account, the Oba was hesitant to sign the treaty.[4] After the British consul Richard Burton visited Benin in 1862 he described it a place of "gratuitous barbarity which stinks of death", a narrative which was publicized in Britain and increased pressure for the territory's incorporation into the British Empire.[3] The treaty itself does not explicitly mention anything about the "bloody customs" that Burton had written about, and instead includes a vague clause about ensuring "the general progress of civilization".[5] While the treaty granted free trade to British merchants operating in the Kingdom of Benin, the Oba persisted in requiring customs duties.[6] Since Major (later Sir) Claude Maxwell Macdonald, the Consul General of the Oil River Protectorate authorities considered the treaty legal and binding, he deemed the Oba's requirements a violation of the accord and thus a hostile act.[7]

Although some historians have suggested that humanitarian motivations were driving British foreign policy in the region,[8] other historians, such as Philip Igbafe, consider that the annexation of Benin was driven largely by economic designs.[5] The treaty itself did not mention any goal that removed the "bloody customs" that Burton had written about.[5]

In 1894, after the capture of Ebrohimi, the trading town of the chief Nana Olomu (the leading Itsekiri trader in the Benin River District) by a combined Royal Navy and Niger Coast Protectorate force, the Kingdom of Benin increased the military presence on its own southern borders. These developments combined with the Colonial Office's refusal to grant approval for an invasion of Benin City scuttled an expedition the Protectorate had planned for early 1895. Even so, between September 1895 and mid-1896 three attempts were made by the Protectorate to enforce the Gallwey Treaty of 1892: firstly by Major P. Copland-Crawford, Vice-Consul of the Benin District; secondly by Ralph Frederick Locke, the Vice-Consul Assistant; and thirdly by Captain Arthur Maling, Commandant of the Niger Coast Protectorate Force detachment based in Sapele.

In March 1896, following price fixing and refusals by Itsekiri middle men to pay the required tributes, the Oba of Benin ordered a cessation of the supply of oil palm produce to them. The trade embargo brought trade in the Benin River region to a standstill, and the British merchants in the region appealed to the Protectorate's Consul-General to "open up" Benin territories and to send the Oba (whom they claimed was an obstruction to their trading activities) into exile. In October 1896 the Acting Consul-General, James Robert Phillips, visited the Benin River District and met with the agents and traders, who convinced him that "there is a future on the Benin River if Benin territories were opened".

The "Benin Massacre" (January 1897)

In November 1896, Phillips, the Vice Consul of a trading post on the African coast, decided to meet with the Oba in Benin City in regards to the trade agreement that the Oba had made with the British but was not keeping. He formally asked his superiors in London for permission to visit Benin City, claiming that the costs of such an expedition would be recouped by trading for ivory. In late December 1896, without waiting for a reply or approval, Phillips embarked on an expedition comprising:[9]

- James Robert Phillips, Acting Consul-General, Niger Coast Protectorate.

- Maj. Copland Crawford, Vice-Council of the Benin and Warri districts.

- Alan Boisragon, Commandant of the Constabulary of the Niger Coast Protectorate.

- Cap. Malling, Niger Coast Protectorate force.

- Dr. Elliot, Medical Officer for Sapele and Benin districts.

- Mr. Ralph Locke, District Commissioner of Warri.

- Mr. Kenneth Campbell, District Commissioner at Sapele.

- Mr. Gordon, trader, Africa Association.

- Mr. Swainson, trader, of Mr. Pinnock's firm.

- Mr. Powis, agent for Millers Brothers palm oil, at Old Calabar.

- Mr. Lyon, Assistant District commissioner at Sapele (waited Gwatto).

- Mr. Baddoo (of Accara, Gold Coast), Consul-General's Chief clerk and Photographer.

- Mr. Jumbo, Consul-General's orderly, and Civil Policeman.

- Mr. , Vice-Council's orderly, and Civil Policeman.

- Mr. Towey, local interpreter.

- Mr. Herbert Clarke, local interpreter.

- Mr. Basilli, local Benin guide.

- Jim, Boisragon's, Kru, manservant.

- 180 Jakri porters to carry their supplies, food, trade goods, presents, cameras, and tents.

- 60 Kru labourers.

Phillips had sent a message to the Oba, claiming that his present mission was to discuss trade and peace and demanding admission to the territory. Ahead of Phillips, he had sent an envoy bearing numerous gifts for trade. It was during this time that the Oba was celebrating Igue festival, and he sent word that he did not wish to see the British at the time, and he would send word in a month or two, when he was ready to receive just Phillips and one Jakri chief.[9]

On 4 January 1897, Phillips and his entire party was ambushed along their journey to Benin City, at Ugbine village near Gwato.[9] British officers and African porters were both slaughtered. Only two British survived their wounds, Alan Boisragon and Ralph Locke. Within the week, news had made it to London of the massacre. This event led to the mounting of the Punitive Expedition.[10][11]

As a result of this attack, the Foreign Office of Britain authorized military action, leading to the "punitive expedition", the purported intention by Moor: »It is imperative that a most severe lesson be given the Kings, Chiefs, and JuJu men of all surrounding countries, that white men cannot be killed with impunity, and that human sacrifices, with the oppression of the weak and poor, must cease.« According to historian Philip Igbafe, the humanitarian and punitive justifications given by Moor ran counter to the economic justifications for military action that he and other members of the Protectorate administration promoted in the months and years before the events of February 1897.[3]

The two British that survived the annihilation of Phillips' expedition,[9] which became known as the 'Benin Massacre', were Captain Alan Maxwell Boisragon, Commandant of the Constabulary of the Niger Coast Protectorate, who had been shot in the right arm and knee, and Ralph Locke, District Commissioner of Warri, who had been shot four times in the arm, and once in the hip.[10]

The punitive expedition (February 1897)

On 12 January 1897, Rear-Admiral Harry Rawson, commander of the Royal Navy forces at the Cape of Good Hope and West Coast of Africa Station,[12] was appointed by the Admiralty to lead a force to invade the Kingdom of Benin and capture the Benin Oba. The operation was named the Benin Punitive Expedition.[9]

On 9 February 1897, the invasion of the Kingdom of Benin began. The British invasion force of about 1,200 Royal Marines, sailors and Niger Coast Protectorate Forces was organised into three columns: the 'Sapoba', 'Gwato' and 'Main' columns. Flotillas of warships (including HMS Philomel and Phoebe) and gunboats approached Benin City from the east and west.[13] The 'Sapoba' and 'Main' columns reached Benin City after ten days of fighting. The 'Gwato' column (under Captain Gallwey) took the same route as that taken by the previous mission and came on the scene of the massacre, finding headless bodies of the victims.[14]

Elspeth Huxley spent some time researching in Benin in 1954, and wrote:[15]

" ... to hear an account of the Benin massacre of 1897 and its sequel from one who had taken part. It is a story that still has power to amaze and horrify, as well as to remind us that the British had motives for pushing into Africa other than the intention to exploit the natives and glorify themselves. Here, for instance, are some extracts from the diary of a surgeon who took part in the expedition.:- 'As we neared Benin City we passed several human sacrifices, live women slaves gagged and pegged on their backs to the ground, the abdominal wall being cut in the form of a cross, and the uninjured gut hanging out. These poor women were allowed to die like this in the sun. Men slaves, with their hands tied at the back and feet lashed together, also gagged, were lying about. As we neared the city, sacrificed human beings were lying in the path and bush—even in the king's compound the sight and stench of them was awful. Dead and mutilated bodies were everywhere – by God! May I never see such sights again! . . .'"[16]

Herbert Walker, a soldier serving in the punitive expedition, believed that the human sacrifices he saw were an attempt by Benin City residents to appease the Gods as they tried to defend themselves from the expedition.[17]

According to professor of African studies, Robin Law, the issue of human sacrifices is an extremely sensitive one and prone to bias. Law suggests that the reported extent of the practice in Benin was exaggerated by the British in order to establish the need for military intervention.[18]

Historian Dan Hicks has described the punitive expedition's actions during their push to Benin City as democidal, claiming that it involved:

"massacres of towns and villages from the air and thus women and children across the whole of the Benin Kingdom, scorching the earth with rockets, fire and mines. Primary among the war crimes was the scale of the killing and bombings of civilian targets."[13]

On 18 February Benin City was captured by the expedition, in spite of its defensive iya. The city was set ablaze, although it has been claimed that this was accidental.

Eight members of the punitive force were recorded as being killed in action during the Benin Expedition; the number of military and civilian casualties amongst the Benin people was not estimated but is thought to have been very high.[13]

The Benin Expedition was described as such:

- "In twenty-nine days a force of 1,200 men, coming from three places between 3000 and 4500 m. from the Benin river, was landed, organized, equipped and provided with transport. Five days later the city of Benin was taken, and in twelve days more the men were re-embarked, and the ships coaled and ready for any further service."[19]

All-in-all, around 5,000 men were mobilised for the expedition, which took place over three weeks.[20]

Aftermath

After the capture of Benin City, houses, sacred sites, ceremonial buildings and palaces of many high-ranking chiefs were looted and many buildings were burned down, including the Palace building itself on Sunday 21 February. There was evidence of previous human sacrifice found by members of the expedition,[21] with journalists from Reuters and the Illustrated London News reporting that the town 'reeked of human blood.'[22] Inside the abandoned palace, a terrible sight was revealed to the British. The Oba in panic of what he had done and in fear of a retaliatory attack, had embarked in a great mass of human sacrifice in order to stave off full disaster. Bodies of those sacrificed by the Oba laid in pits and many hung crucified in trees.[10][11]

_Nabeshi%252C_The_Last_King_(Oba)_Of_Benin.jpg.webp)

The Oba was eventually captured by the British consul-general, Ralph Moor. He was deposed and exiled, with two of his eighty wives, to Calabar.[23] A British Resident was appointed, and six chiefs were hanged in Benin City's marketplace.[13]

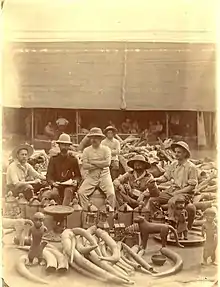

Most of the plunder from the city was retained by the expedition with some 2,500 (official figures) religious artefacts, Benin visual history, mnemonics and artworks being sent to Britain. They include over a thousand metal plaques and sculptures collectively known as the Benin Bronzes. The Admiralty confiscated and auctioned off the war booty to defray the costs of the expedition.[24]

About 40% of the art was accessioned to the British Museum, while other works were given to individual members of the armed forces as spoils of war, and the remainder was sold at auction by the Admiralty to pay for the expedition as early as May 1897 (Stevens Auction Rooms, 38 King Street, London, 25 May 1897; followed by several sales by the ethnographic dealer William Downing Webster, Bicester, between 1898 and 1900). Most of the Benin Bronzes sold at auction were purchased by museums, mainly in Germany. The dispersal of Benin artworks to museums around the world catalysed the beginnings of a long and slow European reassessment of the value of West African art. The Benin art was copied and the style integrated into the art of many European artists and thus had a strong influence on the early formation of modernism in Europe.[25]

The British occupied Benin, which was absorbed into the British Niger Coast Protectorate and eventually into British colonial Nigeria. A general emancipation of slaves followed in the wake of British occupation, and with it came an end to human sacrifice.[26] However, the British instituted a system of drafting locals to work as forced labourers in often poor conditions that were not much better than had been during the previous Benin Empire.[27]

Controversy

There has much debate of why James Phillips set out on the mission to Benin without much weaponry.[4] Some have argued he was going on a peaceful mission. Such commentators argue that the message from the Oba that his festival would not permit him to receive European visitors touched the humanitarian side of Phillips's character because of an incorrect assumption that the festival included human sacrifice.[28] According to Igbafe, this does not explain why Phillips set out before he had received a reply from the Foreign Office to his request where he stated that:

F.O. 2/I02, Phillips to F.O. no. 105 of i6 Nov 1896. 'there is nothing in the shape of a standing army. ... and the inhabitants appear to be if not a peace-loving at any rate a most unwarlike people whose only exploits during many generations had been an occasional quarrel with their neighbours about trade or slave raiding and it appears at least improbable that they have any arms to speak of except the usual number of trade guns... When Captain Gallwey visited the city the only canon he saw were half a dozen old Portuguese guns. They were lying on the grass unmounted'. Compare this with the opinion of his immediate predecessor, Ralph Moor, who was convinced that 'the people in all the villages are no doubt possessed of arms' (F.O. 2/84, Moor to F.O. no. 39 of I2 Sept. 1895).

Igbafe also points to Phillips' November 1896 advocacy of military force regarding Benin, arguing that this is inconsistent with the perception of Phillips as a man of peace in January 1897. Igbafe posits that Phillips was going on a reconnaissance mission and that Phillips' haste to Benin can be explained by a belief that nothing bad would happen to him or his party.[4]

Phillips's journey was has been described by Mona Zutshi Opubor as a period of lull before the outbreak of a violent storm which had been gathering for years with the pressure of traders, consuls and a few visits of armed Europeans to the Benin Empire. The suspicion among the Oba of Benin, therefore, only deepened with Phillips's mission.[29] The previous deportations of the Jaja of Opobo in 1887 and Nana Olomu in 1894 in neighboring British controlled territories may have made the Benin Empire anxious about safety of their Oba and the true intentions of the British.[30] According to Igbafe, evidence at the Oba's trial in September 1897, showed that the people of Benin Empire did not believe that Phillips' party had peaceful intentions, since the capture of Nana, there had been a long expectation of war in Benin.[4]

Movement for repatriation of looted objects

In 2017 a cockerel statue or okukor looted during the 1897 Benin Expedition was removed from the hall of Jesus College, Cambridge, following protests by students of the university.[31] Jesus College's student union passed a motion declaring that the sculpture should be returned. A spokesperson from the university stated that "Jesus College acknowledges the contribution made by students in raising the important but complex question of the rightful location of its Benin bronze, in response to which it has removed the okukor from its hall" and that the university is willing "to discuss and determine the best future for the okukor, including the question of repatriation.[32] On 27 October 2021, the okukor was received by Nigeria's National Commission for Museums and Monuments in a Benin Bronze Restitution Ceremony held and livestreamed by Jesus College.[33][34]

The University of Aberdeen became the first institution to agree to the full repatriation of a Benin Bronze from a museum in March 2021 and handed back a bronze sculpture, depicting the head of an Oba, to the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments on 28 October 2021. It had been purchased by the university at an auction in 1957 and was identified as a Benin bronze in a recent collections review.[35]

Current day policy of the Nigerian government see all repatriated Benin Bronzes turned over to the ownership of Ewuare II, the current Oba of Benin and direct descendant of the ruler of Benin overthrown by the British in 1897. Many descendants of the freed slaves still remain in the Benin area today and thus returning the Benin Bronzes to the descendant of the ruler enriched by their slave trading and human sacrifice has caused much controversy nationally and internationally.[36]

Cultural representations

- Plays relating to the events include Ovonramwen N' Ogbaisi, written by Ola Rotimi (1971); and The Trials of Oba Ovonramwen, written by Ahmed Yerima (1997);

- Visual artists' responses include Tony Phillips' series of prints titled History of the Benin Bronzes (1984);[37] Kerry James Marshall's graphic novel titled Rythm Mastr;[38] and Peju Layiwola's travelling exhibition and edited book called Benin1897.com: Art and the Restitution Question.[39]

- Films covering aspects of the expedition include The Mask (1979), starring Eddie Ugbomah; and Invasion 1897 (2014), directed by Lancelot Oduwa Imasuen.

References

Notes

- Obinyan, T. U. (September 1988). "The Annexation of Benin". Journal of Black Studies. 19 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1177/002193478801900103. JSTOR 2784423. S2CID 142726955.

- Igbafe, Philip A. "Slavery and Emancipation in Benin, 1897-1945". The Journal of African History, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, pp. 409–29. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/180474. Accessed 4 July 2023.

- Igbafe 1970, p. 385.

- Igbafe 1970.

- Igbafe 1970, p. 387.

- Igbafe 1970, p. 390.

- Igbafe 1970, p. 391.

- E.G. Hernon, A. Britain's Forgotten Wars, p.409 (2002)

- Boisragon, Alan Maxwell (1897). The Benin massacre. Smithsonian Libraries. London : Methuen.

- ETNOGRAFÍA. The Tribal Eye. Kingdom of Bronze. Cap. 4/7., retrieved 17 March 2022

- Collison, David; Gyles, Anna Benson (17 June 1975), Kingdom of Bronze, The Tribal Eye, David Attenborough, retrieved 26 May 2023

- "William Loney RN". Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- Dan, Hicks (2020). The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. Pluto Press. pp. 111, 115–6, 123, 132. doi:10.2307/j.ctv18msmcr. ISBN 978-0-7453-4176-7. JSTOR j.ctv18msmcr. S2CID 240965144.

- "Blockade of Crete". The Western Mail. 17 March 1897. hdl:10107/4313320.

- "Four Guineas" Elspeth Huxley, 1954

- "Great Benin: Its Customs, Art and Horrors" by H. Ling Roth. The surgeon was Roth's brother.

- Otzen, Otzen (26 February 2015). "The man who returned his grandfather's looted art". BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- Robin Law, "Human Sacrifice in Pre-Colonial West Africa", in: African Affairs 84 (334), 1985, pp. 53–87

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Benin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 739.

- Dan, Hicks (2020). "The Sacking of Benin City". The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution. Pluto Press. pp. 109–114. doi:10.2307/j.ctv18msmcr.13. ISBN 978-0-7453-4176-7. JSTOR j.ctv18msmcr.13. S2CID 243197979.

- Graham 1965.

- Hernon, A. Britain's Forgotten Wars, p.421 (2002) ISBN 0-7509-3162-0

- Roth, H. Ling (Henry Ling) (1903). Great Benin; its customs, art and horrors. Smithsonian Libraries. Halifax, Eng., F. King & Sons, ltd.

- Home, Robert (1982). City of Blood Revisited: A New Look at the Benin Expedition of 1897. London: Lex Collins, 1982. ISBN 0-8476-4824-9.

- Ben-Amos, Paula Girshick (1999). Art, Innovation, and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Benin. Indiana University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-253-33503-5.

- Igbafe, Philip A., "Slavery and Emancipation in Benin, 1897–1945, The Journal of African History Vol. 16, No. 3 (1975), pp. 418.

- Uyilawa Usuanlele and Victor Osaro Edo, "Migrating out of reach: fugitive Benin communities in colonial Nigeria, 1897-1934", in Femi James Kolapo and Kwabena O. Akurang-Parry (eds.), African agency and European colonialism: latitudes of negotiation and containment: essays in honor of A.S. Kanya-Forstner (2007), pp.76-77

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/180345, R. H. Bacon, Benin the City of Blood (London, I897), 17, [The assumption here again is that the festival meant a holocaust of human beings. The Oba was celebrating the Ague festival, which was one of rededication. This did not involve human sacrifices. See also W. N. M. Geary: Nigeria Under British Rule (London, 1927), II4. ]

- https://open.conted.ox.ac.uk/sites/open.conted.ox.ac.uk/files/resources/Create%20Document/t.%20Victorian%20punitive%20expeditions_Mona%20Zutshi%20Opubor.pdf, https://www.jstor.org/stable/180345

- H. L. Gallwey, 'West African fifty years ago', Journal of the Royal African Society, XL (1942), 65

- "Welcome To News Every Hour: See the Cockerel that is causing serious debate between England and Nigeria (Photo)". Newseveryhour.com. 3 March 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- Weale, Sally (8 March 2016). "Benin bronze row: Cambridge college removes cockerel". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- College, Jesus. "Livestream of Benin Bronze Restitution Ceremony". Jesus College University of Cambridge. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- "Cambridge University college hands back looted cockerel to Nigeria". BBC News. 27 October 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- "Ceremony to complete the return of Benin Bronze | News | The University of Aberdeen". abdn.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- "Benin king to keep bronzes returned by UK | News | The Telegraph".

- "Tony Phillips on the History of the Benin Bronzes I-XII". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ""Rythm Mastr"". Art21. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- Layiwola, Peju (2014). "Making meaning from a fragmented past: 1897 and the creative process". Open Arts Journal (3). doi:10.5456/issn.2050-3679/2014s15pl. ISSN 2050-3679.

Sources

- Home, Robert (1982). City of Blood Revisited • A new look at the Benin expedition of 1897. Londres: Rex Collings, Ltd.

- Igbafe, Philip A. (1970). "The fall of Benin: A Reassessment". Journal of African History. XI (3): 385–400. doi:10.1017/S0021853700010215. JSTOR 180345. S2CID 154621156.

- European traders in Benin to Major Copland Crawford. Reporting the stoppage of trade by the Benin King 1896 Apr 13, Catalogue of the Correspondence and Papers of the Niger Coast Protectorate, 268 3/3/3, p. 240. National Archives of Nigeria Enugu.

- Sir Ralph Moore to Foreign Office. Reporting on the abortive Expedition into Benin. 1895 Sept.12 Catalogue of the Correspondence and Papers of the Niger Coast Protectorate, 268 3/3/3, p. 240. National Archives of Nigeria Enugu

- J. R. Phillips to Foreign Office. Advising the deposition of the Benin King. 17 Nov 1896. Despatches to Foreign Office from Consul-General, Catalogue of the Correspondence and Papers of the Niger Coast Protectorate, 268 3/3/3, p. 240. National Archives of Nigeria Enugu.

- Akenzua, Edun (2000). "The Case of Benin". Appendices to the Minutes of Evidence, Appendix 21, House of Commons, The United Kingdom Parliament, March 2000.

- Ben-Amos, Paula Girshick (1999). Art, Innovation, and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Benin. Indiana University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-253-33503-5.

- Boisragon, Alan (1897). The Benin Massacre. London: Methuen.

- Graham, James D. (1965). "The Slave Trade, Depopulation and Human Sacrifice in Benin History: The General Approach". Cahiers d'Études africaines. V (18): 317–334. doi:10.3406/cea.1965.3035. JSTOR 4390897.

Further reading

- Bacon, R. H. (1897). Benin, The City of Blood. London: Arnold.

- Docherty, Paddy (2021). Blood and Bronze: The British Empire and the Sack of Benin. London: Hurst. ISBN 978-1-78738-456-9.

- Read, Charles Hercules & Dalton, Ormonde Maddock (1899). Antiquities from the City of Benin and from Other Parts of West Africa in the British Museum. London: British Museum.

External links

- The British Museum (2000). Stories of royalty in brass. Collections Multimedia Public Access System, The British Museum, 2000. Retrieved 6 September 2006

- Gott, Richard (1997). The Looting of Benin. The Independent, 22 Feb.1997. Republished at ARM Press Cutting. (See also related GIF image of the article Battle royal for Benin relics). Retrieved 9 October 2006.

- Soni, Darshana (1997). The British and the Benin Bronzes. ARM Information Sheet 4, Campaign for the Return of the Benin Bronzes, 1997. Retrieved 9 October 2006.

- An account of an engagement during the conflict by Reginald Bacon RN