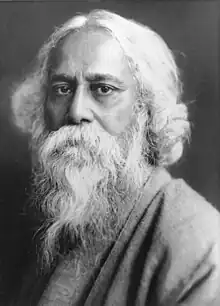

Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore FRAS (/rəˈbɪndrənɑːt tæˈɡɔːr/ ⓘ; pronounced [roˈbindɾonatʰ ˈʈʰakuɾ];[1] 7 May 1861[2] – 8 August 1941[3]) was an Indian poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter.[4][5][6] He reshaped Bengali literature and music as well as Indian art with Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Author of the "profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful" poetry of Gitanjali,[7] he became in 1913 the first non-European and the first lyricist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.[8] Tagore's poetic songs were viewed as spiritual and mercurial; where his elegant prose and magical poetry were widely popular in the Indian subcontinent.[9] He was a fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society. Referred to as "the Bard of Bengal",[10][5][6] Tagore was known by sobriquets: Gurudeb, Kobiguru, and Biswokobi.[lower-alpha 1]

Rabindranath Tagore | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর |

| Born | Rabindranath Tagore 7 May 1861 Calcutta, Bengal Presidency, British India (present-day Kolkata, West Bengal, India) |

| Died | 8 August 1941 (aged 80) Calcutta, Bengal Presidency, British India (present-day Kolkata, West Bengal, India) |

| Pen name | Bhanusimha |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | |

| Citizenship | British India (1861–1941) |

| Period | Bengali Renaissance |

| Literary movement | Contextual Modernism |

| Notable works | |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1913 |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5, including Rathindranath Tagore |

| Relatives | Tagore family |

| Signature | |

A Bengali Brahmin from Calcutta with ancestral gentry roots in Burdwan district[12] and Jessore, Tagore wrote poetry as an eight-year-old.[13] At the age of sixteen, he released his first substantial poems under the pseudonym Bhānusiṃha ("Sun Lion"), which were seized upon by literary authorities as long-lost classics.[14] By 1877 he graduated to his first short stories and dramas, published under his real name. As a humanist, universalist, internationalist, and ardent critic of nationalism,[15] he denounced the British Raj and advocated independence from Britain. As an exponent of the Bengal Renaissance, he advanced a vast canon that comprised paintings, sketches and doodles, hundreds of texts, and some two thousand songs; his legacy also endures in his founding of Visva-Bharati University.[16][17]

Tagore modernised Bengali art by spurning rigid classical forms and resisting linguistic strictures. His novels, stories, songs, dance-dramas, and essays spoke to topics political and personal. Gitanjali (Song Offerings), Gora (Fair-Faced) and Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World) are his best-known works, and his verse, short stories, and novels were acclaimed—or panned—for their lyricism, colloquialism, naturalism, and unnatural contemplation. His compositions were chosen by two nations as national anthems: India's "Jana Gana Mana" and Bangladesh's "Amar Shonar Bangla". The Sri Lankan national anthem was also inspired by his work.[18]

Family history

The name Tagore is the anglicised transliteration of Thakur.[19] The original surname of the Tagores was Kushari. They were Pirali Brahmin ('Pirali' historically carried a stigmatized and pejorative connotation)[20][21] who originally belonged to a village named Kush in the district named Burdwan in West Bengal. The biographer of Rabindranath Tagore, Prabhat Kumar Mukhopadhyaya wrote in the first volume of his book Rabindrajibani O Rabindra Sahitya Prabeshak that

The Kusharis were the descendants of Deen Kushari, the son of Bhatta Narayana; Deen was granted a village named Kush (in Burdwan zilla) by Maharaja Kshitisura, he became its chief and came to be known as Kushari.[12]

Life and events

Early life: 1861–1878

The last two days a storm has been raging, similar to the description in my song—Jhauro jhauro borishe baridhara [... amidst it] a hapless, homeless man drenched from top to toe standing on the roof of his steamer [...] the last two days I have been singing this song over and over [...] as a result the pelting sound of the intense rain, the wail of the wind, the sound of the heaving Gorai River, [...] have assumed a fresh life and found a new language and I have felt like a major actor in this new musical drama unfolding before me.

— Letter to Indira Devi.[22]

The youngest of 13 surviving children, Tagore (nicknamed "Rabi") was born on 7 May 1861 in the Jorasanko mansion in Calcutta,[23] the son of Debendranath Tagore (1817–1905) and Sarada Devi (1830–1875).[lower-alpha 2]

Tagore was raised mostly by servants; his mother had died in his early childhood and his father travelled widely.[29] The Tagore family was at the forefront of the Bengal renaissance. They hosted the publication of literary magazines; theatre and recitals of Bengali and Western classical music featured there regularly. Tagore's father invited several professional Dhrupad musicians to stay in the house and teach Indian classical music to the children.[30] Tagore's oldest brother Dwijendranath was a philosopher and poet. Another brother, Satyendranath, was the first Indian appointed to the elite and formerly all-European Indian Civil Service. Yet another brother, Jyotirindranath, was a musician, composer, and playwright.[31] His sister Swarnakumari became a novelist.[32] Jyotirindranath's wife Kadambari Devi, slightly older than Tagore, was a dear friend and powerful influence. Her abrupt suicide in 1884, soon after he married, left him profoundly distraught for years.[33]

Tagore largely avoided classroom schooling and preferred to roam the manor or nearby Bolpur and Panihati, which the family visited.[34][35] His brother Hemendranath tutored and physically conditioned him—by having him swim the Ganges or trek through hills, by gymnastics, and by practising judo and wrestling. He learned drawing, anatomy, geography and history, literature, mathematics, Sanskrit, and English—his least favourite subject.[36] Tagore loathed formal education—his scholarly travails at the local Presidency College spanned a single day. Years later he held that proper teaching does not explain things; proper teaching stokes curiosity:[37]

After his upanayan (coming-of-age rite) at age eleven, Tagore and his father left Calcutta in February 1873 to tour India for several months, visiting his father's Santiniketan estate and Amritsar before reaching the Himalayan hill station of Dalhousie. There Tagore read biographies, studied history, astronomy, modern science, and Sanskrit, and examined the classical poetry of Kālidāsa.[38][39] During his 1-month stay at Amritsar in 1873 he was greatly influenced by melodious gurbani and nanak bani being sung at Golden Temple for which both father and son were regular visitors. He mentions about this in his My Reminiscences (1912)

The golden temple of Amritsar comes back to me like a dream. Many a morning have I accompanied my father to this Gurudarbar of the Sikhs in the middle of the lake. There the sacred chanting resounds continually. My father, seated amidst the throng of worshippers, would sometimes add his voice to the hymn of praise, and finding a stranger joining in their devotions they would wax enthusiastically cordial, and we would return loaded with the sanctified offerings of sugar crystals and other sweets.[40]

He wrote 6 poems relating to Sikhism and a number of articles in Bengali children's magazine about Sikhism.[41]

- Poems on Guru Gobind Singh: নিষ্ফল উপহার Nishfal-upahaar(1888, translated as "Futile Gift"), গুরু গোবিন্দ Guru Gobinda (1899) and শেষ শিক্ষা Shesh Shiksha (1899, translated as "Last Teachings") [42]

- Poem on Banda Bahadur: বন্দী বীর Bandi-bir (The Prisoner Warrior written in 1888 or 1898) [43]

- Poem on Bhai Torusingh: প্রার্থনাতীত দান (prarthonatit dan - Unsolicited gift) written in 1888 or 1898 [44]

- Poem on Nehal Singh: নীহাল সিংহ (Nihal Singh) written in 1935. [45]

Tagore returned to Jorosanko and completed a set of major works by 1877, one of them a long poem in the Maithili style of Vidyapati. As a joke, he claimed that these were the lost works of newly discovered 17th-century Vaiṣṇava poet Bhānusiṃha.[46] Regional experts accepted them as the lost works of the fictitious poet.[47] He debuted in the short-story genre in Bengali with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").[48][49] Published in the same year, Sandhya Sangit (1882) includes the poem "Nirjharer Swapnabhanga" ("The Rousing of the Waterfall").

Shelaidaha: 1878–1901

Because Debendranath wanted his son to become a barrister, Tagore enrolled at a public school in Brighton, East Sussex, England in 1878.[22] He stayed for several months at a house that the Tagore family owned near Brighton and Hove, in Medina Villas; in 1877 his nephew and niece—Suren and Indira Devi, the children of Tagore's brother Satyendranath—were sent together with their mother, Tagore's sister-in-law, to live with him.[50] He briefly read law at University College London, but again left, opting instead for independent study of Shakespeare's plays Coriolanus, and Antony and Cleopatra and the Religio Medici of Thomas Browne. Lively English, Irish, and Scottish folk tunes impressed Tagore, whose own tradition of Nidhubabu-authored kirtans and tappas and Brahmo hymnody was subdued.[22][51] In 1880 he returned to Bengal degree-less, resolving to reconcile European novelty with Brahmo traditions, taking the best from each.[52] After returning to Bengal, Tagore regularly published poems, stories, and novels. These had a profound impact within Bengal itself but received little national attention.[53] In 1883 he married 10-year-old[54] Mrinalini Devi, born Bhabatarini, 1873–1902 (this was a common practice at the time). They had five children, two of whom died in childhood.[55]

In 1890 Tagore began managing his vast ancestral estates in Shelaidaha (today a region of Bangladesh); he was joined there by his wife and children in 1898. Tagore released his Manasi poems (1890), among his best-known work.[56] As Zamindar Babu, Tagore criss-crossed the Padma River in command of the Padma, the luxurious family barge (also known as "budgerow"). He collected mostly token rents and blessed villagers who in turn honoured him with banquets—occasionally of dried rice and sour milk.[57] He met Gagan Harkara, through whom he became familiar with Baul Lalon Shah, whose folk songs greatly influenced Tagore.[58] Tagore worked to popularise Lalon's songs. The period 1891–1895, Tagore's Sadhana period, named after one of his magazines, was his most productive;[29] in these years he wrote more than half the stories of the three-volume, 84-story Galpaguchchha.[48] Its ironic and grave tales examined the voluptuous poverty of an idealised rural Bengal.[59]

Santiniketan: 1901–1932

In 1901 Tagore moved to Santiniketan to found an ashram with a marble-floored prayer hall—The Mandir—an experimental school, groves of trees, gardens, a library.[60] There his wife and two of his children died. His father died in 1905. He received monthly payments as part of his inheritance and income from the Maharaja of Tripura, sales of his family's jewellery, his seaside bungalow in Puri, and a derisory 2,000 rupees in book royalties.[61] He gained Bengali and foreign readers alike; he published Naivedya (1901) and Kheya (1906) and translated poems into free verse.

In 1912, Tagore translated his 1910 work Gitanjali into English. While on a trip to London, he shared these poems with admirers including William Butler Yeats and Ezra Pound. London's India Society published the work in a limited edition, and the American magazine Poetry published a selection from Gitanjali.[62] In November 1913, Tagore learned he had won that year's Nobel Prize in Literature: the Swedish Academy appreciated the idealistic—and for Westerners—accessible nature of a small body of his translated material focused on the 1912 Gitanjali: Song Offerings.[63] He was awarded a knighthood by King George V in the 1915 Birthday Honours, but Tagore renounced it after the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre.[64] Renouncing the knighthood, Tagore wrote in a letter addressed to Lord Chelmsford, the then British Viceroy of India, "The disproportionate severity of the punishments inflicted upon the unfortunate people and the methods of carrying them out, we are convinced, are without parallel in the history of civilised governments...The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in their incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of my country men."[65][66]

In 1919, he was invited by the president and chairman of Anjuman-e-Islamia, Syed Abdul Majid to visit Sylhet for the first time. The event attracted over 5000 people.[67]

In 1921, Tagore and agricultural economist Leonard Elmhirst set up the "Institute for Rural Reconstruction", later renamed Shriniketan or "Abode of Welfare", in Surul, a village near the ashram. With it, Tagore sought to moderate Gandhi's Swaraj protests, which he occasionally blamed for British India's perceived mental – and thus ultimately colonial – decline.[68] He sought aid from donors, officials, and scholars worldwide to "free village[s] from the shackles of helplessness and ignorance" by "vitalis[ing] knowledge".[69][70] In the early 1930s he targeted ambient "abnormal caste consciousness" and untouchability. He lectured against these, he penned Dalit heroes for his poems and his dramas, and he campaigned—successfully—to open Guruvayoor Temple to Dalits.[71][72]

Twilight years: 1932–1941

Dutta and Robinson describe this phase of Tagore's life as being one of a "peripatetic litterateur". It affirmed his opinion that human divisions were shallow. During a May 1932 visit to a Bedouin encampment in the Iraqi desert, the tribal chief told him that "Our Prophet has said that a true Muslim is he by whose words and deeds not the least of his brother-men may ever come to any harm ..." Tagore confided in his diary: "I was startled into recognizing in his words the voice of essential humanity."[73] To the end Tagore scrutinized orthodoxy—and in 1934, he struck. That year, an earthquake hit Bihar and killed thousands. Gandhi hailed it as seismic karma, as divine retribution avenging the oppression of Dalits. Tagore rebuked him for his seemingly ignominious implications.[74] He mourned the perennial poverty of Calcutta and the socioeconomic decline of Bengal and detailed this newly plebeian aesthetics in an unrhymed hundred-line poem whose technique of searing double-vision foreshadowed Satyajit Ray's film Apur Sansar.[75][76] Fifteen new volumes appeared, among them prose-poem works Punashcha (1932), Shes Saptak (1935), and Patraput (1936). Experimentation continued in his prose-songs and dance-dramas— Chitra (1914), Shyama (1939), and Chandalika (1938)— and in his novels— Dui Bon (1933), Malancha (1934), and Char Adhyay (1934).[77]

Clouds come floating into my life, no longer to carry rain or usher storm, but to add color to my sunset sky.

—Verse 292, Stray Birds, 1916.

Tagore's remit expanded to science in his last years, as hinted in Visva-Parichay, a 1937 collection of essays. His respect for scientific laws and his exploration of biology, physics, and astronomy informed his poetry, which exhibited extensive naturalism and verisimilitude.[78] He wove the process of science, the narratives of scientists, into stories in Se (1937), Tin Sangi (1940), and Galpasalpa (1941). His last five years were marked by chronic pain and two long periods of illness. These began when Tagore lost consciousness in late 1937; he remained comatose and near death for a time. This was followed in late 1940 by a similar spell, from which he never recovered. Poetry from these valetudinary years is among his finest.[79][80] A period of prolonged agony ended with Tagore's death on 8 August 1941, aged 80.[23] He was in an upstairs room of the Jorasanko mansion in which he grew up.[81][82] The date is still mourned.[83] A. K. Sen, brother of the first chief election commissioner, received dictation from Tagore on 30 July 1941, a day prior to a scheduled operation: his last poem.[84]

I'm lost in the middle of my birthday. I want my friends, their touch, with the earth's last love. I will take life's final offering, I will take the human's last blessing. Today my sack is empty. I have given completely whatever I had to give. In return if I receive anything—some love, some forgiveness—then I will take it with me when I step on the boat that crosses to the festival of the wordless end.

Travels

Our passions and desires are unruly, but our character subdues these elements into a harmonious whole. Does something similar to this happen in the physical world? Are the elements rebellious, dynamic with individual impulse? And is there a principle in the physical world which dominates them and puts them into an orderly organization?

— Interviewed by Einstein, 14 April 1930.[85]

Between 1878 and 1932, Tagore set foot in more than thirty countries on five continents.[86] In 1912, he took a sheaf of his translated works to England, where they gained attention from missionary and Gandhi protégé Charles F. Andrews, Irish poet William Butler Yeats, Ezra Pound, Robert Bridges, Ernest Rhys, Thomas Sturge Moore, and others.[87] Yeats wrote the preface to the English translation of Gitanjali; Andrews joined Tagore at Santiniketan. In November 1912 Tagore began touring the United States[88] and the United Kingdom, staying in Butterton, Staffordshire with Andrews's clergymen friends.[89] From May 1916 until April 1917, he lectured in Japan[90] and the United States.[91] He denounced nationalism.[92] His essay "Nationalism in India" was scorned and praised; it was admired by Romain Rolland and other pacifists.[93]

Shortly after returning home the 63-year-old Tagore accepted an invitation from the Peruvian government. He travelled to Mexico. Each government pledged US$100,000 to his school to commemorate the visits.[94] A week after his 6 November 1924 arrival in Buenos Aires,[95] an ill Tagore shifted to the Villa Miralrío at the behest of Victoria Ocampo. He left for home in January 1925. In May 1926 Tagore reached Naples; the next day he met Mussolini in Rome.[96] Their warm rapport ended when Tagore pronounced upon Il Duce's fascist finesse.[97] He had earlier enthused: "[w]without any doubt he is a great personality. There is such a massive vigor in that head that it reminds one of Michael Angelo's chisel." A "fire-bath" of fascism was to have educed "the immortal soul of Italy ... clothed in quenchless light".[98]

On 1 November 1926 Tagore arrived at Hungary and spent some time on the shore of Lake Balaton in the city of Balatonfüred, recovering from heart problems at a sanitarium. He planted a tree, and a bust statue was placed there in 1956 (a gift from the Indian government, the work of Rasithan Kashar, replaced by a newly gifted statue in 2005) and the lakeside promenade still bears his name since 1957.[99]

On 14 July 1927 Tagore and two companions began a four-month tour of Southeast Asia. They visited Bali, Java, Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, Penang, Siam, and Singapore. The resultant travelogues compose Jatri (1929).[100] In early 1930 he left Bengal for a nearly year-long tour of Europe and the United States. Upon returning to Britain—and as his paintings were exhibited in Paris and London—he lodged at a Birmingham Quaker settlement. He wrote his Oxford Hibbert Lectures[lower-alpha 3] and spoke at the annual London Quaker meet.[101] There, addressing relations between the British and the Indians – a topic he would tackle repeatedly over the next two years – Tagore spoke of a "dark chasm of aloofness".[102] He visited Aga Khan III, stayed at Dartington Hall, toured Denmark, Switzerland, and Germany from June to mid-September 1930, then went on into the Soviet Union.[103] In April 1932 Tagore, intrigued by the Persian mystic Hafez, was hosted by Reza Shah Pahlavi.[104][105] In his other travels, Tagore interacted with Henri Bergson, Albert Einstein, Robert Frost, Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells, and Romain Rolland.[106][107] Visits to Persia and Iraq (in 1932) and Sri Lanka (in 1933) composed Tagore's final foreign tour, and his dislike of communalism and nationalism only deepened.[73] Vice-president of India M. Hamid Ansari has said that Rabindranath Tagore heralded the cultural rapprochement between communities, societies and nations much before it became the liberal norm of conduct. Tagore was a man ahead of his time. He wrote in 1932, while on a visit to Iran, that "each country of Asia will solve its own historical problems according to its strength, nature and needs, but the lamp they will each carry on their path to progress will converge to illuminate the common ray of knowledge."[108]

Works

Known mostly for his poetry, Tagore wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas, and thousands of songs. Of Tagore's prose, his short stories are perhaps most highly regarded; he is indeed credited with originating the Bengali-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic, and lyrical nature. Such stories mostly borrow from the lives of common people. Tagore's non-fiction grappled with history, linguistics, and spirituality. He wrote autobiographies. His travelogues, essays, and lectures were compiled into several volumes, including Europe Jatrir Patro (Letters from Europe) and Manusher Dhormo (The Religion of Man). His brief chat with Einstein, "Note on the Nature of Reality", is included as an appendix to the latter. On the occasion of Tagore's 150th birthday, an anthology (titled Kalanukromik Rabindra Rachanabali) of the total body of his works is currently being published in Bengali in chronological order. This includes all versions of each work and fills about eighty volumes.[109] In 2011, Harvard University Press collaborated with Visva-Bharati University to publish The Essential Tagore, the largest anthology of Tagore's works available in English; it was edited by Fakrul Alam and Radha Chakravarthy and marks the 150th anniversary of Tagore's birth.[110]

Drama

Tagore's experiences with drama began when he was sixteen, with his brother Jyotirindranath. He wrote his first original dramatic piece when he was twenty — Valmiki Pratibha which was shown at the Tagore's mansion. Tagore stated that his works sought to articulate "the play of feeling and not of action". In 1890 he wrote Visarjan (an adaptation of his novella Rajarshi), which has been regarded as his finest drama. In the original Bengali language, such works included intricate subplots and extended monologues. Later, Tagore's dramas used more philosophical and allegorical themes. The play Dak Ghar (The Post Office; 1912), describes the child Amal defying his stuffy and puerile confines by ultimately "fall[ing] asleep", hinting his physical death. A story with borderless appeal—gleaning rave reviews in Europe—Dak Ghar dealt with death as, in Tagore's words, "spiritual freedom" from "the world of hoarded wealth and certified creeds".[111][112] Another is Tagore's Chandalika (Untouchable Girl), which was modelled on an ancient Buddhist legend describing how Ananda, the Gautama Buddha's disciple, asks a tribal girl for water.[113] In Raktakarabi ("Red" or "Blood Oleanders") is an allegorical struggle against a kleptocrat king who rules over the residents of Yaksha puri.[114]

Chitrangada, Chandalika, and Shyama are other key plays that have dance-drama adaptations, which together are known as Rabindra Nritya Natya.

Short stories

.jpg.webp)

Tagore began his career in short stories in 1877—when he was only sixteen—with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").[115] With this, Tagore effectively invented the Bengali-language short story genre.[116] The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore's "Sadhana" period (named for one of Tagore's magazines). This period was among Tagore's most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume Galpaguchchha, which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories.[115] Such stories usually showcase Tagore's reflections upon his surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with). Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the "Sadhana" period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore's life in the common villages of, among others, Patisar, Shajadpur, and Shilaida while managing the Tagore family's vast landholdings.[115] There, he beheld the lives of India's poor and common people; Tagore thereby took to examining their lives with a penetrative depth and feeling that was singular in Indian literature up to that point.[117] In particular, such stories as "Kabuliwala" ("The Fruitseller from Kabul", published in 1892), "Kshudita Pashan" ("The Hungry Stones") (August 1895), and "Atithi" ("The Runaway", 1895) typified this analytic focus on the downtrodden.[118] Many of the other Galpaguchchha stories were written in Tagore's Sabuj Patra period from 1914 to 1917, also named after one of the magazines that Tagore edited and heavily contributed to.[115]

Novels

Tagore wrote eight novels and four novellas, among them Chaturanga, Shesher Kobita, Char Odhay, and Noukadubi. Ghare Baire (The Home and the World)—through the lens of the idealistic zamindar protagonist Nikhil—excoriates rising Indian nationalism, terrorism, and religious zeal in the Swadeshi movement; a frank expression of Tagore's conflicted sentiments, it emerged from a 1914 bout of depression. The novel ends in Hindu-Muslim violence and Nikhil's—likely mortal—wounding.[119]

Gora raises controversial questions regarding the Indian identity. As with Ghare Baire, matters of self-identity (jāti), personal freedom, and religion are developed in the context of a family story and love triangle.[120] In it an Irish boy orphaned in the Sepoy Mutiny is raised by Hindus as the titular gora—"whitey". Ignorant of his foreign origins, he chastises Hindu religious backsliders out of love for the indigenous Indians and solidarity with them against his hegemon-compatriots. He falls for a Brahmo girl, compelling his worried foster father to reveal his lost past and cease his nativist zeal. As a "true dialectic" advancing "arguments for and against strict traditionalism", it tackles the colonial conundrum by "portray[ing] the value of all positions within a particular frame [...] not only syncretism, not only liberal orthodoxy, but the extremist reactionary traditionalism he defends by an appeal to what humans share." Among these Tagore highlights "identity [...] conceived of as dharma."[121]

In Jogajog (Relationships), the heroine Kumudini—bound by the ideals of Śiva-Sati, exemplified by Dākshāyani—is torn between her pity for the sinking fortunes of her progressive and compassionate elder brother and his foil: her roue of a husband. Tagore flaunts his feminist leanings; pathos depicts the plight and ultimate demise of women trapped by pregnancy, duty, and family honor; he simultaneously trucks with Bengal's putrescent landed gentry.[122] The story revolves around the underlying rivalry between two families—the Chatterjees, aristocrats now on the decline (Biprodas) and the Ghosals (Madhusudan), representing new money and new arrogance. Kumudini, Biprodas' sister, is caught between the two as she is married off to Madhusudan. She had risen in an observant and sheltered traditional home, as had all her female relations.

Others were uplifting: Shesher Kobita—translated twice as Last Poem and Farewell Song—is his most lyrical novel, with poems and rhythmic passages written by a poet protagonist. It contains elements of satire and postmodernism and has stock characters who gleefully attack the reputation of an old, outmoded, oppressively renowned poet who, incidentally, goes by a familiar name: "Rabindranath Tagore". Though his novels remain among the least-appreciated of his works, they have been given renewed attention via film adaptations by Ray and others: Chokher Bali and Ghare Baire are exemplary. In the first, Tagore inscribes Bengali society via its heroine: a rebellious widow who would live for herself alone. He pillories the custom of perpetual mourning on the part of widows, who were not allowed to remarry, who were consigned to seclusion and loneliness. Tagore wrote of it: "I have always regretted the ending".

Poetry

Internationally, Gitanjali (Bengali: গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore's best-known collection of poetry, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. Tagore was the first non-European to receive a Nobel Prize in Literature and second non-European to receive a Nobel Prize after Theodore Roosevelt.[123]

Besides Gitanjali, other notable works include Manasi, Sonar Tori ("Golden Boat"), Balaka ("Wild Geese" — the title being a metaphor for migrating souls)[124]

Tagore's poetic style, which proceeds from a lineage established by 15th- and 16th-century Vaishnava poets, ranges from classical formalism to the comic, visionary, and ecstatic. He was influenced by the atavistic mysticism of Vyasa and other rishi-authors of the Upanishads, the Bhakti-Sufi mystic Kabir, and Ramprasad Sen.[125] Tagore's most innovative and mature poetry embodies his exposure to Bengali rural folk music, which included mystic Baul ballads such as those of the bard Lalon.[126][127] These, rediscovered and re-popularized by Tagore, resemble 19th-century Kartābhajā hymns that emphasize inward divinity and rebellion against bourgeois bhadralok religious and social orthodoxy.[128][129] During his Shelaidaha years, his poems took on a lyrical voice of the moner manush, the Bāuls' "man within the heart" and Tagore's "life force of his deep recesses", or meditating upon the jeevan devata—the demiurge or the "living God within".[22] This figure connected with divinity through appeal to nature and the emotional interplay of human drama. Such tools saw use in his Bhānusiṃha poems chronicling the Radha-Krishna romance, which were repeatedly revised over the course of seventy years.[130][131]

Later, with the development of new poetic ideas in Bengal – many originating from younger poets seeking to break with Tagore's style – Tagore absorbed new poetic concepts, which allowed him to further develop a unique identity. Examples of this include Africa and Camalia, which are among the better known of his latter poems.

Songs (Rabindra Sangeet)

Tagore was a prolific composer with around 2,230 songs to his credit.[132] His songs are known as rabindrasangit ("Tagore Song"), which merges fluidly into his literature, most of which—poems or parts of novels, stories, or plays alike—were lyricized. Influenced by the thumri style of Hindustani music, they ran the entire gamut of human emotion, ranging from his early dirge-like Brahmo devotional hymns to quasi-erotic compositions.[133] They emulated the tonal color of classical ragas to varying extents. Some songs mimicked a given raga's melody and rhythm faithfully, others newly blended elements of different ragas.[134] Yet about nine-tenths of his work was not bhanga gaan, the body of tunes revamped with "fresh value" from select Western, Hindustani, Bengali folk and other regional flavors "external" to Tagore's own ancestral culture.[22]

In 1971, Amar Shonar Bangla became the national anthem of Bangladesh. It was written – ironically – to protest the 1905 Partition of Bengal along communal lines: cutting off the Muslim-majority East Bengal from Hindu-dominated West Bengal was to avert a regional bloodbath. Tagore saw the partition as a cunning plan to stop the independence movement, and he aimed to rekindle Bengali unity and tar communalism. Jana Gana Mana was written in shadhu-bhasha, a Sanskritised form of Bengali,[135] and is the first of five stanzas of the Brahmo hymn Bharot Bhagyo Bidhata that Tagore composed. It was first sung in 1911 at a Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress[136] and was adopted in 1950 by the Constituent Assembly of the Republic of India as its national anthem.

Sri Lanka's National Anthem was inspired by his work.[18]

For Bengalis, the songs' appeal, stemming from the combination of emotive strength and beauty described as surpassing even Tagore's poetry, was such that the Modern Review observed that "[t]here is in Bengal no cultured home where Rabindranath's songs are not sung or at least attempted to be sung... Even illiterate villagers sing his songs".[137] Tagore influenced sitar maestro Vilayat Khan and sarodiyas Buddhadev Dasgupta and Amjad Ali Khan.[134]

Art works

At sixty, Tagore took up drawing and painting; successful exhibitions of his many works—which made a debut appearance in Paris upon encouragement by artists he met in the south of France[139]—were held throughout Europe. He was likely red, green color blind, resulting in works that exhibited strange color schemes and off-beat aesthetics. Tagore was influenced by numerous styles, including scrimshaw by the Malanggan people of northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, Haida carvings from the Pacific Northwest region of North America, and woodcuts by the German Max Pechstein.[138] His artist's eye for handwriting was revealed in the simple artistic and rhythmic leitmotifs embellishing the scribbles, cross-outs, and word layouts of his manuscripts. Some of Tagore's lyrics corresponded in a synesthetic sense with particular paintings.[22]

Surrounded by several painters Rabindranath had always wanted to paint. Writing and music, playwriting and acting came to him naturally and almost without training, as it did to several others in his family, and in even greater measure. But painting eluded him. Yet he tried repeatedly to master the art and there are several references to this in his early letters and reminiscence. In 1900 for instance, when he was nearing forty and already a celebrated writer, he wrote to Jagadishchandra Bose, "You will be surprised to hear that I am sitting with a sketchbook drawing. Needless to say, the pictures are not intended for any salon in Paris, they cause me not the least suspicion that the national gallery of any country will suddenly decide to raise taxes to acquire them. But, just as a mother lavishes most affection on her ugliest son, so I feel secretly drawn to the very skill that comes to me least easily." He also realized that he was using the eraser more than the pencil, and dissatisfied with the results he finally withdrew, deciding it was not for him to become a painter.[140]

India's National Gallery of Modern Art lists 102 works by Tagore in its collections.[142][143]

In 1937, Tagore's paintings were removed from Berlin's baroque Crown Prince Palace by the Nazi regime and five were included in the inventory of "degenerate art" compiled by the Nazis in 1941–1942.[144]

Politics

Tagore opposed imperialism and supported Indian nationalists,[145][146][147] and these views were first revealed in Manast, which was mostly composed in his twenties.[56] Evidence produced during the Hindu–German Conspiracy Trial and latter accounts affirm his awareness of the Ghadarites and stated that he sought the support of Japanese Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake and former Premier Ōkuma Shigenobu.[148] Yet he lampooned the Swadeshi movement; he rebuked it in The Cult of the Charkha, an acrid 1925 essay.[149] According to Amartya Sen, Tagore rebelled against strongly nationalist forms of the independence movement, and he wanted to assert India's right to be independent without denying the importance of what India could learn from abroad.[150] He urged the masses to avoid victimology and instead seek self-help and education, and he saw the presence of British administration as a "political symptom of our social disease". He maintained that, even for those at the extremes of poverty, "there can be no question of blind revolution"; preferable to it was a "steady and purposeful education".[151][152]

So I repeat we never can have a true view of man unless we have a love for him. Civilisation must be judged and prized, not by the amount of power it has developed, but by how much it has evolved and given expression to, by its laws and institutions, the love of humanity.

— Sādhanā: The Realisation of Life, 1916.[153]

Such views enraged many. He escaped assassination—and only narrowly—by Indian expatriates during his stay in a San Francisco hotel in late 1916; the plot failed when his would-be assassins fell into argument.[154] Tagore wrote songs lionizing the Indian independence movement.[155] Two of Tagore's more politically charged compositions, "Chitto Jetha Bhayshunyo" ("Where the Mind is Without Fear") and "Ekla Chalo Re" ("If They Answer Not to Thy Call, Walk Alone"), gained mass appeal, with the latter favored by Gandhi.[156] Though somewhat critical of Gandhian activism,[157] Tagore was key in resolving a Gandhi–Ambedkar dispute involving separate electorates for untouchables, thereby mooting at least one of Gandhi's fasts "unto death".[158][159]

Repudiation of knighthood

Tagore renounced his knighthood in response to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919. In the repudiation letter to the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, he wrote[160]

The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part, wish to stand, shorn, of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen who, for their so called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings.

Santiniketan and Visva-Bharati

Tagore despised rote classroom schooling: in "The Parrot's Training", a bird is caged and force-fed textbook pages—to death.[161][162] Visiting Santa Barbara in 1917, Tagore conceived a new type of university: he sought to "make Santiniketan the connecting thread between India and the world [and] a world center for the study of humanity somewhere beyond the limits of nation and geography."[154] The school, which he named Visva-Bharati,[lower-alpha 4] had its foundation stone laid on 24 December 1918 and was inaugurated precisely three years later.[163] Tagore employed a brahmacharya system: gurus gave pupils personal guidance—emotional, intellectual, and spiritual. Teaching was often done under trees. He staffed the school, he contributed his Nobel Prize monies,[164] and his duties as steward-mentor at Santiniketan kept him busy: mornings he taught classes; afternoons and evenings he wrote the students' textbooks.[165] He fundraised widely for the school in Europe and the United States between 1919 and 1921.[166]

Theft of Nobel Prize

On 25 March 2004, Tagore's Nobel Prize was stolen from the safety vault of the Visva-Bharati University, along with several other of his belongings.[167] On 7 December 2004, the Swedish Academy decided to present two replicas of Tagore's Nobel Prize, one made of gold and the other made of bronze, to the Visva-Bharati University.[168] It inspired the fictional film Nobel Chor. In 2016, a baul singer named Pradip Bauri, accused of sheltering the thieves, was arrested.[169][170]

Impact and legacy

Every year, many events pay tribute to Tagore: Kabipranam, his birth anniversary, is celebrated by groups scattered across the globe; the annual Tagore Festival held in Urbana, Illinois (US); Rabindra Path Parikrama walking pilgrimages from Kolkata to Santiniketan; and recitals of his poetry, which are held on important anniversaries.[88][171][172] Bengali culture is fraught with this legacy: from language and arts to history and politics. Amartya Sen deemed Tagore a "towering figure", a "deeply relevant and many-sided contemporary thinker".[172][150] Tagore's Bengali originals—the 1939 Rabīndra Rachanāvalī—is canonized as one of his nation's greatest cultural treasures, and he was roped into a reasonably humble role: "the greatest poet India has produced".[173]

Tagore was renowned throughout much of Europe, North America, and East Asia. He co-founded Dartington Hall School, a progressive coeducational institution;[174] in Japan, he influenced such figures as Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata.[175] In colonial Vietnam Tagore was a guide for the restless spirit of the radical writer and publicist Nguyen An Ninh[176] Tagore's works were widely translated into English, Dutch, German, Spanish, and other European languages by Czech Indologist Vincenc Lesný,[177] French Nobel laureate André Gide, Russian poet Anna Akhmatova,[178] former Turkish Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit,[179] and others. In the United States, Tagore's lecturing circuits, particularly those of 1916–1917, were widely attended and wildly acclaimed. Some controversies[lower-alpha 5] involving Tagore, possibly fictive, trashed his popularity and sales in Japan and North America after the late 1920s, concluding with his "near total eclipse" outside Bengal.[9] Yet a latent reverence of Tagore was discovered by an astonished Salman Rushdie during a trip to Nicaragua.[185]

By way of translations, Tagore influenced Chileans Pablo Neruda and Gabriela Mistral; Mexican writer Octavio Paz; and Spaniards José Ortega y Gasset, Zenobia Camprubí, and Juan Ramón Jiménez. In the period 1914–1922, the Jiménez-Camprubí pair produced twenty-two Spanish translations of Tagore's English corpus; they heavily revised The Crescent Moon and other key titles. In these years, Jiménez developed "naked poetry".[186] Ortega y Gasset wrote that "Tagore's wide appeal [owes to how] he speaks of longings for perfection that we all have [...] Tagore awakens a dormant sense of childish wonder, and he saturates the air with all kinds of enchanting promises for the reader, who [...] pays little attention to the deeper import of Oriental mysticism". Tagore's works circulated in free editions around 1920—alongside those of Plato, Dante, Cervantes, Goethe, and Tolstoy.

Tagore was deemed over-rated by some. Graham Greene doubted that "anyone but Mr. Yeats can still take his poems very seriously." Several prominent Western admirers—including Pound and, to a lesser extent, even Yeats—criticized Tagore's work. Yeats, unimpressed with his English translations, railed against that "Damn Tagore [...] We got out three good books, Sturge Moore and I, and then, because he thought it more important to see and know English than to be a great poet, he brought out sentimental rubbish and wrecked his reputation. Tagore does not know English, no Indian knows English."[9][187] William Radice, who "English[ed]" his poems, asked: "What is their place in world literature?"[188] He saw him as "kind of counter-cultur[al]", bearing "a new kind of classicism" that would heal the "collapsed romantic confusion and chaos of the 20th century."[187][189] The translated Tagore was "almost nonsensical",[190] and subpar English offerings reduced his trans-national appeal:

Anyone who knows Tagore's poems in their original Bengali cannot feel satisfied with any of the translations (made with or without Yeats's help). Even the translations of his prose works suffer, to some extent, from distortion. E.M. Forster noted [of] The Home and the World [that] '[t]he theme is so beautiful,' but the charms have 'vanished in translation,' or perhaps 'in an experiment that has not quite come off.'

Museums

There are eight Tagore museums, three in India and five in Bangladesh:

- Rabindra Bharati Museum, at Jorasanko Thakur Bari, Kolkata, India

- Tagore Memorial Museum, at Shilaidaha Kuthibadi, Shilaidaha, Bangladesh

- Rabindra Memorial Museum at Shahzadpur Kachharibari, Shahzadpur, Bangladesh

- Rabindra Bhavan Museum, in Santiniketan, India

- Rabindra Museum, in Mungpoo, near Kalimpong, India

- Patisar Rabindra Kacharibari, Patisar, Atrai, Naogaon, Bangladesh

- Pithavoge Rabindra Memorial Complex, Pithavoge, Rupsha, Khulna, Bangladesh

- Rabindra Complex, Dakkhindihi village, Phultala Upazila, Khulna, Bangladesh

Jorasanko Thakur Bari (Bengali: House of the Thakurs; anglicised to Tagore) in Jorasanko, north of Kolkata, is the ancestral home of the Tagore family. It is currently located on the Rabindra Bharati University campus at 6/4 Dwarakanath Tagore Lane[191] Jorasanko, Kolkata 700007.[192] It is the house in which Tagore was born, and also the place where he spent most of his childhood and where he died on 7 August 1941.

List of works

Who are you, reader, reading my poems a hundred years hence?

I cannot send you one single flower from this wealth of the spring, one single streak of gold from yonder clouds.

Open your doors and look abroad.

From your blossoming garden gather fragrant memories of the vanished flowers of an hundred years before.

In the joy of your heart may you feel the living joy that sang one spring morning, sending its glad voice across an hundred years.

— The Gardener, 1915[193]

The SNLTR hosts the 1415 BE edition of Tagore's complete Bengali works. Tagore Web also hosts an edition of Tagore's works, including annotated songs. Translations are found at Project Gutenberg and Wikisource. More sources are below.

Original

| Bengali title | Transliterated title | Translated title | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| ভানুসিংহ ঠাকুরের পদাবলী | Bhānusiṃha Ṭhākurer Paḍāvalī | Songs of Bhānusiṃha Ṭhākur | 1884 |

| মানসী | Manasi | The Ideal One | 1890 |

| সোনার তরী | Sonar Tari | The Golden Boat | 1894 |

| গীতাঞ্জলি | Gitanjali | Song Offerings | 1910 |

| গীতিমাল্য | Gitimalya | Wreath of Songs | 1914 |

| বলাকা | Balaka | The Flight of Cranes | 1916 |

| Bengali title | Transliterated title | Translated title | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| বাল্মিকী প্রতিভা | Valmiki-Pratibha | The Genius of Valmiki | 1881 |

| কালমৃগয়া | Kal-Mrigaya | The Fatal Hunt | 1882 |

| মায়ার খেলা | Mayar Khela | The Play of Illusions | 1888 |

| বিসর্জন | Visarjan | The Sacrifice | 1890 |

| চিত্রাঙ্গদা | Chitrangada | Chitrangada | 1892 |

| রাজা | Raja | The King of the Dark Chamber | 1910 |

| ডাকঘর | Dak Ghar | The Post Office | 1912 |

| অচলায়তন | Achalayatan | The Immovable | 1912 |

| মুক্তধারা | Muktadhara | The Waterfall | 1922 |

| রক্তকরবী | Raktakarabi | Red Oleanders | 1926 |

| চণ্ডালিকা | Chandalika | The Untouchable Girl | 1933 |

| Bengali title | Transliterated title | Translated title | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| নষ্টনীড় | Nastanirh | The Broken Nest | 1901 |

| গোরা | Gora | Fair-Faced | 1910 |

| ঘরে বাইরে | Ghare Baire | The Home and the World | 1916 |

| যোগাযোগ | Yogayog | Crosscurrents | 1929 |

| Bengali title | Transliterated title | Translated title | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| জীবনস্মৃতি | Jivansmriti | My Reminiscences | 1912 |

| ছেলেবেলা | Chhelebela | My Boyhood Days | 1940 |

| Title | Year |

|---|---|

| Thought Relics | 1921[original 1] |

Translated

| Year | Work |

|---|---|

| 1914 | Chitra[text 1] |

| 1922 | Creative Unity[text 2] |

| 1913 | The Crescent Moon[text 3] |

| 1917 | The Cycle of Spring[text 4] |

| 1928 | Fireflies |

| 1916 | Fruit-Gathering[text 5] |

| 1916 | The Fugitive[text 6] |

| 1913 | The Gardener[text 7] |

| 1912 | Gitanjali: Song Offerings[text 8] |

| 1920 | Glimpses of Bengal[text 9] |

| 1921 | The Home and the World[text 10] |

| 1916 | The Hungry Stones[text 11] |

| 1991 | I Won't Let you Go: Selected Poems |

| 1914 | The King of the Dark Chamber[text 12] |

| 2012 | Letters from an Expatriate in Europe |

| 2003 | The Lover of God |

| 1918 | Mashi[text 13] |

| 1928 | My Boyhood Days |

| 1917 | My Reminiscences[text 14] |

| 1917 | Nationalism |

| 1914 | The Post Office[text 15] |

| 1913 | Sadhana: The Realisation of Life[text 16] |

| 1997 | Selected Letters |

| 1994 | Selected Poems |

| 1991 | Selected Short Stories |

| 1915 | Songs of Kabir[text 17] |

| 1916 | The Spirit of Japan[text 18] |

| 1918 | Stories from Tagore[text 19] |

| 1916 | Stray Birds[text 20] |

| 1913 | Vocation[194] |

| 1921 | The Wreck |

In popular culture

- Rabindranath Tagore is a 1961 Indian documentary film written and directed by Satyajit Ray, released during the birth centenary of Tagore. It was produced by the Government of India's Films Division.

- Serbian composer Darinka Simic-Mitrovic used Tagore's text for her song cycle Gradinar in 1962.[195]

- In 1969, American composer E. Anne Schwerdtfeger was commissioned to compose Two Pieces, a work for women's chorus based on text by Tagore.[196]

- In Sukanta Roy's Bengali film Chhelebela (2002) Jisshu Sengupta portrayed Tagore.[197]

- In Bandana Mukhopadhyay's Bengali film Chirosakha He (2007) Sayandip Bhattacharya played Tagore.[198]

- In Rituparno Ghosh's Bengali documentary film Jeevan Smriti (2011) Samadarshi Dutta played Tagore.[199]

- In Suman Ghosh's Bengali film Kadambari (2015) Parambrata Chatterjee portrayed Tagore.[200]

See also

References

Notes

- Gurudev translates as "divine mentor", Bishokobi translates as "poet of the world" and Kobiguru translates as "great poet".[11]

- Tagore was born at No. 6 Dwarkanath Tagore Lane, Jorasanko – the address of the main mansion (the Jorasanko Thakurbari) inhabited by the Jorasanko branch of the Tagore clan, which had earlier suffered an acrimonious split. Jorasanko was located in the Bengali section of Calcutta, near Chitpur Road.[24][25] Dwarkanath Tagore was his paternal grandfather.[26] Debendranath had formulated the Brahmoist philosophies espoused by his friend Ram Mohan Roy, and became focal in Brahmo society after Roy's death.[27][28]

- On the "idea of the humanity of our God, or the divinity of Man the Eternal".

- Etymology of "Visva-Bharati": from the Sanskrit for "world" or "universe" and the name of a Rigvedic goddess ("Bharati") associated with Saraswati, the Hindu patron of learning.[163] "Visva-Bharati" also translates as "India in the World".

- Tagore was no stranger to controversy: his dealings with Indian nationalists Subhas Chandra Bose[9] and Rash Behari Bose,[180] his yen for Soviet Communism,[181][182] and papers confiscated from Indian nationalists in New York allegedly implicating Tagore in a plot to overthrow the Raj via German funds.[183] These destroyed Tagore's image—and book sales—in the United States.[180] His relations with and ambivalent opinion of Mussolini revolted many;[98] close friend Romain Rolland despaired that "[h]e is abdicating his role as moral guide of the independent spirits of Europe and India".[184]

Citations

- "How to pronounce রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর". forvo.com.

- 25 Baisakh 1268(Bangabda)

- 22 Shravan 1368(Bangabda)

- Lubet, Alex (17 October 2016). "Tagore, not Dylan: The first lyricist to win the Nobel Prize for literature was actually Indian". Quartz India. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- "Anita Desai and Andrew Robinson – The Modern Resonance of Rabindranath Tagore". On Being. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Stern, Robert W. (2001). Democracy and Dictatorship in South Asia: Dominant Classes and Political Outcomes in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-275-97041-3.

- Newman, Henry (1921). The Calcutta Review. University of Calcutta. p. 252.

I have also found that Bombay is India, Satara is India, Bangalore is India, Madras is India, Delhi, Lahore, the Khyber, Lucknow, Calcutta, Cuttack, Shillong, etc., are all India.

- The Nobel Foundation.

- O'Connell 2008.

- Sen 1997.

- "Work of Rabindranath Tagore celebrated in London". BBC News. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Sil 2005.

-

- Tagore, Rathindranath (December 1978). On the edges of time (New ed.). Greenwood Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-313-20760-0.

- Mukherjee, Mani Shankar (May 2010). "Timeless Genius". Pravasi Bharatiya: 89, 90.

- Thompson, Edward (1948). Rabindranath Tagore : Poet And Dramatist. Oxford University Press. p. 13.

- Tagore 1984, p. xii.

- Thompson 1926, pp. 27–28; Dasgupta 1993, p. 20.

- "Nationalism is a Great Menace" Tagore and Nationalism, by Radhakrishnan M. and Roychowdhury D. from Hogan, P. C.; Pandit, L. (2003), Rabindranath Tagore: Universality and Tradition, pp 29–40

- "Visva-Bharti-Facts and Figures at a Glance". Archived from the original on 23 May 2007.

- Datta 2002, p. 2; Kripalani 2005a, pp. 6–8; Kripalani 2005b, pp. 2–3; Thompson 1926, p. 12.

-

- de Silva, K. M.; Wriggins, Howard (1988). J. R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka: a Political Biography – Volume One: The First Fifty Years. University of Hawaii Press. p. 368. ISBN 0-8248-1183-6.

- "Man of the series: Nobel laureate Tagore". The Times of India. Times News Network. 3 April 2011.

- "How Tagore inspired Sri Lanka's national anthem". IBN Live. 8 May 2012. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012.

- Nasrin, Mithun B.; Wurff, W. A. M. Van Der (2015). Colloquial Bengali. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-317-30613-9.

- Ahmad, Zarin (14 June 2018). Delhi's Meatscapes: Muslim Butchers in a Transforming Mega-City. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-909538-4.

- Fraser, Bashabi (15 September 2019). Rabindranath Tagore. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-178-8.

- Ghosh 2011.

- "Rabindranath Tagore – Facts". Nobel Foundation.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 34.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 37.

- The News Today 2011.

- Roy 1977, pp. 28–30.

- Tagore 1997b, pp. 8–9.

- Thompson 1926, p. 20.

- Som 2010, p. 16.

- Tagore 1997b, p. 10.

- Sree, S. Prasanna (2003). Woman in the novels of Shashi Deshpande : a study (1st ed.). New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. p. 13. ISBN 81-7625-381-2. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Paul, S. K. (1 January 2006). The Complete Poems of Rabindranath Tagore's Gitanjali: Texts and Critical Evaluation. Sarup & Sons. p. 2. ISBN 978-81-7625-660-5. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Thompson 1926, pp. 21–24.

- Das 2009.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 48–49.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 50.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 55–56.

- Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 91.

- "A journey with my Father". My Reminiscences.

- Dev, Amiya (2014). "Tagore and Sikhism". Mainstream Weekly.

- Dev, Amiya (2014). "Tagore and Sikhism". Mainstream Weekly.

- Dev, Amiya (2014). "Tagore and Sikhism". Mainstream Weekly.

- Dev, Amiya (2014). "Tagore and Sikhism". Mainstream Weekly.

- Dev, Amiya (2014). "Tagore and Sikhism". Mainstream Weekly.

- Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 3.

- Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 3.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 45.

- Tagore 1997b, p. 265.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 68.

- Thompson 1926, p. 31.

- Tagore 1997b, pp. 11–12.

- Guha, Ramachandra (2011). Makers of Modern India. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University. p. 171.

- Dutta, Krishna; Robinson, Andrew (1997). Selected Letters of Rabindranath Tagore. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-521-59018-1. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 373.

- Scott 2009, p. 10.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 109–111.

- Chowdury, A. A. (1992), Lalon Shah, Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangla Academy, ISBN 984-07-2597-1

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 109.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 133.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 139–140.

- "Rabindranath Tagore". Poetry Foundation. 7 May 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- Hjärne 1913.

- Anil Sethi; Guha; Khullar; Nair; Prasad; Anwar; Singh; Mohapatra, eds. (2014). "The Rowlatt Satyagraha". Our Pasts: Volume 3, Part 2 (History text book) (Revised 2014 ed.). India: NCERT. p. 148. ISBN 978-81-7450-838-6.

- "Letter from Rabindranath Tagore to Lord Chelmsford, Viceroy of India". Digital Anthropology Resources for Teaching, Columbia University and the London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- "Tagore renounced his Knighthood in protest for Jalianwalla Bagh mass killing". The Times of India. 13 April 2011.

- Mortada, Syed Ahmed. "When Tagore came to Sylhet".

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 239–240.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 242.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 308–309.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 303.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 309.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 317.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 312–313.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 335–338.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 342.

- "A 100 years ago, Rabindranath Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize for poetry. But his novels are more enduring". The Hindu. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Tagore & Radice 2004, p. 28.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 338.

- Indo-Asian News Service 2005.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 367.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 363.

- The Daily Star 2009.

- Sigi 2006, p. 89.

- Tagore 1930, pp. 222–225.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 374–376.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 178–179.

- University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 1–2.

- Nathan, Richard (12 March 2021). "Changing Nations: The Japanese Girl With a Book". Red Circle Authors.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 206.

- Hogan & Pandit 2003, pp. 56–58.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 182.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 253.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 256.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 267.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 270–271.

- Kundu 2009.

- "The Tagore Connection". Free Press Journal. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 1.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 289–292.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 303–304.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 292–293.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 2.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 315.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 99.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, pp. 100–103.

- "Vice President speaks on Rabindranath Tagore". Newkerala.com. 8 May 2012. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- Pandey 2011.

- The Essential Tagore, Harvard University Press, retrieved 19 December 2011

- Tagore 1997b, pp. 21–22.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, pp. 123–124.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 124.

- Ray 2007, pp. 147–148.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 45.

- Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 265.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, pp. 45–46

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 46

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 192–194.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 154–155.

- Hogan 2000, pp. 213–214.

- Mukherjee 2004.

- "All Nobel Prizes". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 1.

- Roy 1977, p. 201.

- Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 94.

- Urban 2001, p. 18.

- Urban 2001, pp. 6–7.

- Urban 2001, p. 16.

- Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 95.

- Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 7.

- Sanjukta Dasgupta; Chinmoy Guha (2013). Tagore-At Home in the World. SAGE Publications. p. 254. ISBN 978-81-321-1084-2.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 94.

- Dasgupta 2001.

- "10 things to know about Indian national Anthem". Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- Chatterjee, Monish R. (13 August 2003). "Tagore and Jana Gana Mana". countercurrents.org.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 359.

- Dyson 2001.

- Tagore 1997b, p. 222.

- R. Siva Kumar (2011) The Last Harvest: Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore.

- Som 2010, pp. 144–145.

- "National Gallery of Modern Art – Mumbai:Virtual Galleries". Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- "National Gallery of Modern Art:Collections". Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- "Rabindranath Tagore: When Hitler purged India Nobel laureate's paintings". BBC News. 21 November 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- Tagore 1997b, p. 127.

- Tagore 1997b, p. 210.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 304.

- Brown 1948, p. 306.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 261.

- Sen, Amartya. "Tagore And His India". countercurrents.org. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- Tagore 1997b, pp. 239–240.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 181.

- Tagore 1916, p. 111.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 204.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 215–216.

- Chakraborty & Bhattacharya 2001, p. 157.

- Mehta 1999.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 306–307.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 339.

- "Tagore renounced his Knighthood in protest for Jalianwalla Bagh mass killing". The Times of India. Mumbai. 13 April 2011. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- Tagore 1997b, p. 267.

- Tagore & Pal 2004.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 220.

- Roy 1977, p. 175.

- Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 27.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 221.

- "Tagore's Nobel Prize stolen". The Times of India. The Times Group. 25 March 2004. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "Sweden to present India replicas of Tagore's Nobel". The Times of India. The Times Group. 7 December 2004. Archived from the original on 10 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "Tagore's Nobel medal theft: Baul singer arrested". The Times of India. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- "Tagore's Nobel Medal Theft: Folk Singer Arrested From Bengal". News18. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- Chakrabarti 2001.

- Hatcher 2001.

- Kämpchen 2003.

- Farrell 2000, p. 162.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 202.

- Hue-Tam Ho Tai, Radicalism and the Origins of the Vietnamese Revolution, p. 76-82

- Cameron 2006.

- Sen 2006, p. 90.

- Kinzer 2006.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 214.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 297.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 214–215.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 212.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 273.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 255.

- Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 254–255.

- Bhattacharya 2001.

- Tagore & Radice 2004, p. 26.

- Tagore & Radice 2004, pp. 26–31.

- Tagore & Radice 2004, pp. 18–19.

- "Rabindra Bharti Museum (Jorasanko Thakurbari)". Archived from the original on 9 February 2012.

- "Tagore House (Jorasanko Thakurbari) – Kolkata". wikimapia.org.

- Tagore & Ray 2007, p. 104.

- Vocation, Ratna Sagar, 2007, p. 64, ISBN 978-81-8332-175-4

- Cohen, Aaron I. (1987). International Encyclopedia of Women Composers. Books & Music (US). ISBN 978-0-9617485-2-4.

- Heinrich, Adel (1991). Organ and harpsichord music by women composers : an annotated catalog. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-38790-6. OCLC 650307517.

- "Chhelebela will capture the poet's childhood". rediff.com. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "Tagore or touch-him-not". The Times of India. 13 July 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "Celebrating Tagore". The Hindu. 7 August 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- Banerjee, Kathakali (12 January 2017). "Kadambari explores Tagore and his sis-in-law's relationship responsibly". Times of India. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

Bibliography

Primary

Anthologies

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1952), Collected Poems and Plays of Rabindranath Tagore, Macmillan Publishing (published January 1952), ISBN 978-0-02-615920-3

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1984), Some Songs and Poems from Rabindranath Tagore, East-West Publications, ISBN 978-0-85692-055-4

- Tagore, Rabindranath (2011), Alam, F.; Chakravarty, R. (eds.), The Essential Tagore, Harvard University Press (published 15 April 2011), p. 323, ISBN 978-0-674-05790-6

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1961), Chakravarty, A. (ed.), A Tagore Reader, Beacon Press (published 1 June 1961), ISBN 978-0-8070-5971-5

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1997a), Dutta, K.; Robinson, A. (eds.), Selected Letters of Rabindranath Tagore, Cambridge University Press (published 28 June 1997), ISBN 978-0-521-59018-1

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1997b), Dutta, K.; Robinson, A. (eds.), Rabindranath Tagore: An Anthology, Saint Martin's Press (published November 1997), ISBN 978-0-312-16973-2

- Tagore, Rabindranath (2007), Ray, M. K. (ed.), The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore, vol. 1, Atlantic Publishing (published 10 June 2007), ISBN 978-81-269-0664-2

Originals

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1916), Sādhanā: The Realisation of Life, Macmillan

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1930), The Religion of Man, Macmillan

Translations

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1914), The Post Office, translated by Mukerjea, D., London: Macmillan

- Tagore, Rabindranath (2004), translated by Pal, P. B., "The Parrot's Tale", Parabaas (published 1 December 2004)

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1995), Rabindranath Tagore: Selected Poems, translated by Radice, W. (1st ed.), London: Penguin (published 1 June 1995), ISBN 978-0-14-018366-5

- Tagore, Rabindranath (2004), Particles, Jottings, Sparks: The Collected Brief Poems, translated by Radice, W, Angel Books (published 28 December 2004), ISBN 978-0-946162-66-6

- Tagore, Rabindranath (2003), Rabindranath Tagore: Lover of God, Lannan Literary Selections, translated by Stewart, T. K.; Twichell, C., Copper Canyon Press (published 1 November 2003), ISBN 978-1-55659-196-9

Secondary

Articles

- Bhattacharya, S. (2001), "Translating Tagore", The Hindu, Chennai, India (published 2 September 2001), archived from the original on 1 November 2003, retrieved 9 September 2011

- Brown, G. T. (1948), "The Hindu Conspiracy: 1914–1917", The Pacific Historical Review, University of California Press (published August 1948), 17 (3): 299–310, doi:10.2307/3634258, ISSN 0030-8684, JSTOR 3634258

- Cameron, R. (2006), "Exhibition of Bengali Film Posters Opens in Prague", Radio Prague (published 31 March 2006), retrieved 29 September 2011

- Chakrabarti, I. (2001), "A People's Poet or a Literary Deity?", Parabaas (published 15 July 2001), retrieved 17 September 2011

- Das, S. (2009), "Tagore's Garden of Eden", The Telegraph, Calcutta, India (published 2 August 2009), archived from the original on 3 March 2010, retrieved 29 September 2011

- Dasgupta, A. (2001), "Rabindra-Sangeet as a Resource for Indian Classical Bandishes", Parabaas (published 15 July 2001), retrieved 17 September 2011

- Dyson, K. K. (2001), "Rabindranath Tagore and His World of Colours", Parabaas (published 15 July 2001), retrieved 26 November 2009

- Ghosh, B. (2011), "Inside the World of Tagore's Music", Parabaas (published August 2011), retrieved 17 September 2011

- Harvey, J. (1999), In Quest of Spirit: Thoughts on Music, University of California Press, archived from the original on 6 May 2001, retrieved 10 September 2011

- Hatcher, B. A. (2001), "Aji Hote Satabarsha Pare: What Tagore Says to Us a Century Later", Parabaas (published 15 July 2001), retrieved 28 September 2011

- Hjärne, H. (1913), The Nobel Prize in Literature 1913: Rabindranath Tagore—Award Ceremony Speech, Nobel Foundation (published 10 December 1913), retrieved 17 September 2011

- Jha, N. (1994), "Rabindranath Tagore" (PDF), PROSPECTS: The Quarterly Review of Education, Paris: UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, 24 (3/4): 603–19, doi:10.1007/BF02195291, S2CID 144526531, retrieved 30 August 2011

- Kämpchen, M. (2003), "Rabindranath Tagore in Germany", Parabaas (published 25 July 2003), retrieved 28 September 2011

- Kinzer, S. (2006), "Bülent Ecevit, Who Turned Turkey Toward the West, Dies", The New York Times (published 5 November 2006), retrieved 28 September 2011

- Kundu, K. (2009), "Mussolini and Tagore", Parabaas (published 7 May 2009), retrieved 17 September 2011

- Mehta, S. (1999), "The First Asian Nobel Laureate", Time (published 23 August 1999), archived from the original on 10 February 2001, retrieved 30 August 2011

- Meyer, L. (2004), "Tagore in The Netherlands", Parabaas (published 15 July 2004), retrieved 30 August 2011

- Mukherjee, M. (2004), "Yogayog ("Nexus") by Rabindranath Tagore: A Book Review", Parabaas (published 25 March 2004), retrieved 29 September 2011

- Pandey, J. M. (2011), "Original Rabindranath Tagore Scripts in Print Soon", The Times of India (published 8 August 2011), archived from the original on 24 September 2012, retrieved 1 September 2011

- O'Connell, K. M. (2008), "Red Oleanders (Raktakarabi) by Rabindranath Tagore—A New Translation and Adaptation: Two Reviews", Parabaas (published December 2008), retrieved 28 September 2011

- Radice, W. (2003), "Tagore's Poetic Greatness", Parabaas (published 7 May 2003), retrieved 30 August 2011

- Sen, A. (1997), "Tagore and His India", The New York Review of Books, retrieved 30 August 2011

- Sil, N. P. (2005), "Devotio Humana: Rabindranath's Love Poems Revisited", Parabaas (published 15 February 2005), retrieved 13 August 2009

Books

- Ray, Niharranjan (1967). An Artist in Life. University of Kerala.

- Ayyub, A. S. (1980), Tagore's Quest, Papyrus

- Chakraborty, S. K.; Bhattacharya, P. (2001), Leadership and Power: Ethical Explorations, Oxford University Press (published 16 August 2001), ISBN 978-0-19-565591-9

- Dasgupta, T. (1993), Social Thought of Rabindranath Tagore: A Historical Analysis, Abhinav Publications (published 1 October 1993), ISBN 978-81-7017-302-1

- Datta, P. K. (2002), Rabindranath Tagore's The Home and the World: A Critical Companion (1st ed.), Permanent Black (published 1 December 2002), ISBN 978-81-7824-046-6

- Dutta, K.; Robinson, A. (1995), Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man, Saint Martin's Press (published December 1995), ISBN 978-0-312-14030-4

- Farrell, G. (2000), Indian Music and the West, Clarendon Paperbacks Series (3 ed.), Oxford University Press (published 9 March 2000), ISBN 978-0-19-816717-4

- Hogan, P. C. (2000), Colonialism and Cultural Identity: Crises of Tradition in the Anglophone Literatures of India, Africa, and the Caribbean, State University of New York Press (published 27 January 2000), ISBN 978-0-7914-4460-3

- Hogan, P. C.; Pandit, L. (2003), Rabindranath Tagore: Universality and Tradition, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press (published May 2003), ISBN 978-0-8386-3980-1

- Kripalani, K. (2005), Dwarkanath Tagore: A Forgotten Pioneer—A Life, National Book Trust of India, ISBN 978-81-237-3488-0

- Kripalani, K. (2005), Tagore—A Life, National Book Trust of India, ISBN 978-81-237-1959-7

- Lago, M. (1977), Rabindranath Tagore, Boston: Twayne Publishers (published April 1977), ISBN 978-0-8057-6242-6

- Lifton, B. J.; Wiesel, E. (1997), The King of Children: The Life and Death of Janusz Korczak, St. Martin's Griffin (published 15 April 1997), ISBN 978-0-312-15560-5

- Prasad, A. N.; Sarkar, B. (2008), Critical Response To Indian Poetry in English, Sarup and Sons, ISBN 978-81-7625-825-8

- Ray, M. K. (2007), Studies on Rabindranath Tagore, vol. 1, Atlantic (published 1 October 2007), ISBN 978-81-269-0308-5, retrieved 16 September 2011

- Roy, B. K. (1977), Rabindranath Tagore: The Man and His Poetry, Folcroft Library Editions, ISBN 978-0-8414-7330-0

- Scott, J. (2009), Bengali Flower: 50 Selected Poems from India and Bangladesh (published 4 July 2009), ISBN 978-1-4486-3931-1

- Sen, A. (2006), The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture, and Identity (1st ed.), Picador (published 5 September 2006), ISBN 978-0-312-42602-6

- Sigi, R. (2006), Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore—A Biography, Diamond Books (published 1 October 2006), ISBN 978-81-89182-90-8

- Sinha, S. (2015), The Dialectic of God: The Theosophical Views Of Tagore and Gandhi, Partridge Publishing India, ISBN 978-1-4828-4748-2

- Som, R. (2010), Rabindranath Tagore: The Singer and His Song, Viking (published 26 May 2010), ISBN 978-0-670-08248-3, OL 23720201M

- Thompson, E. (1926), Rabindranath Tagore: Poet and Dramatist, Pierides Press, ISBN 978-1-4067-8927-0

- Urban, H. B. (2001), Songs of Ecstasy: Tantric and Devotional Songs from Colonial Bengal, Oxford University Press (published 22 November 2001), ISBN 978-0-19-513901-3

Other

- "68th Death Anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore", The Daily Star, Dhaka (published 7 August 2009), 2009, retrieved 29 September 2011

- "Recitation of Tagore's Poetry of Death", Hindustan Times, Indo-Asian News Service, 2005

- "Archeologists Track Down Tagore's Ancestral Home in Khulna", The News Today (published 28 April 2011), 2011, archived from the original on 28 March 2012, retrieved 9 September 2011

- The Nobel Prize in Literature 1913, The Nobel Foundation, retrieved 14 August 2009

- History of the Tagore Festival, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Tagore Festival Committee, archived from the original on 13 June 2015, retrieved 29 November 2009

Texts

Original

- Thought Relics, Internet Sacred Text Archive

Translated

- Chitra at Project Gutenberg

- Creative Unity at Project Gutenberg

- The Crescent Moon at Project Gutenberg

- The Cycle of Spring at Project Gutenberg

- Fruit-Gathering at Project Gutenberg

- The Fugitive at Project Gutenberg

- The Gardener at Project Gutenberg

- Gitanjali at Project Gutenberg

- Glimpses of Bengal at Project Gutenberg

- The Home and the World at Project Gutenberg

- The Hungry Stones at Project Gutenberg

- The King of the Dark Chamber at Project Gutenberg

- Mashi at Project Gutenberg

- My Reminiscences at Project Gutenberg

- The Post Office at Project Gutenberg

- Sadhana: The Realisation of Life at Project Gutenberg

- Songs of Kabir at Project Gutenberg

- The Spirit of Japan at Project Gutenberg

- Stories from Tagore at Project Gutenberg

- Stray Birds at Project Gutenberg

Further reading

- Abu Zakaria, G., ed. (2011). Rabindranath Tagore—Wanderer zwischen Welten. Klemm and Oelschläger. ISBN 978-3-86281-018-5. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Bhattacharya, Sabyasachi (2011). Rabindranath Tagore: an interpretation. New Delhi: Viking, Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-670-08455-5.

- Chaudhuri, A., ed. (2004). The Vintage Book of Modern Indian Literature (1st ed.). Vintage (published 9 November 2004). ISBN 978-0-375-71300-2.

- Deutsch, A.; Robinson, A., eds. (1989). The Art of Rabindranath Tagore (1st ed.). Monthly Review Press (published August 1989). ISBN 978-0-233-98359-2.

- Shamsud Doulah, A. B. M. (2016). Rabindranath Tagore, the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, and the British Raj: Some Untold Stories. Partridge Publishing Singapore. ISBN 978-1-4828-6403-8.

- Sinha, Satya (2015). The Dialectic of God: The Theosophical Views Of Tagore and Gandhi. Partridge Publishing India. ISBN 978-1-4828-4748-2.

External links

| Library resources about Rabindranath Tagore |

| By Rabindranath Tagore |

|---|

- Rabindranath Tagore at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Rabindranath Tagore at IMDb

- School of Wisdom

- Newspaper clippings about Rabindranath Tagore in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

Analyses

- Ezra Pound: "Rabindranath Tagore", The Fortnightly Review, March 1913

- Mary Lago Collection, University of Missouri

Audiobooks

- Works by Rabindranath Tagore at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Texts

- Works by Rabindranath Tagore in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Bichitra: Online Tagore Variorum

- Works by Rabindranath Tagore at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Rabindranath Tagore at Internet Archive

Talks

.jpg.webp)