Rimush

Rimush (or Rimuš, 𒌷𒈬𒍑 Ri-mu-uš) was the second king of the Akkadian Empire. He was the son of Sargon of Akkad and Queen Tashlultum. He was succeeded by his brother Manishtushu, and was an uncle of Naram-Sin of Akkad. Rimush reported having a statue of himself made out of tin, then a recent introduction to the region.[2] His sister was Enheduana, considered earliest known named author in world history.[3] Their was a city, Dur-Rimuš (Fortress of Rimush), located near Tell Ishchali and Khafajah.[4]

| Rimush 𒌷𒈬𒍑 | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Head of a ruler, ca. 2300–2000 BC, Iran or Mesopotamia. Metropolitan Museum of Art.[1] | |

| King of the Akkadian Empire | |

| Reign | c. 2279 BC – 2270 BC |

| Predecessor | Sargon of Akkad |

| Successor | Manishtushu |

| Dynasty | Dynasty of Akkad |

| Father | Sargon of Akkad |

| Mother | Tashlultum |

Background

According to the Sumerian King List, his reign lasted 9 years (though variant copies read 7 or 15 years.) There is one surviving year-name for an unknown year in his reign: "mu ud-nun{ki} / adab{ki} hul-a = Year in which Adab was destroyed". Tradition gives that he was assassinated, as the Bārûtu, “art of the diviner”, a first millennium compendium of extispicy, records “Omen of king Rimuš, whom his courtiers killed with their seals”.[5] He was succeeded by his brother Manishtushu.[6][7] The Ur III version of the Sumerian King List inverts the order of Rimush and Manishtushu.[8][9] A number of his votive offerings have been found in excavated temples in several Mesopotamian cities.[10]

Destruction of Sumerian city-states

According to his inscriptions, he faced widespread revolts, and had to reconquer the cities of Ur, Umma, Adab, Lagash, Der, and Kazallu from rebellious ensis:[12]

"Rimuš, king of the world, in battle over Adab and Zabalam was victorious, and 15,718 men he struck down, and 14,576 captives he took. Further, Meskigala, governor of Adab, he captured, and Lugalgalzu, governor of Zabalam, he captured. Their cities he conquered, and their walls he destroyed. Further, from their two cities many men he expelled, and to annihilation he consigned them"

"Rīmuš, king of the world, in battle over the cities of Umma and Ki.An was victorious, and 8,900 men he struck down, and 3,480 captives he took. Further, the governor of Umma, he captured, the governor of Ki.An he captured. Further, their cities he conquered, and their walls he destroyed. Further, in their cities 3,600 men he expelled, and to annihilation he consigned them"

— Inscription of Rimus.[14]

Only one year name is preserved for Rimush, and it says "Year in which Adab was destroyed".[15]

Rimush introduced mass slaughter and large scale destruction of the Sumerian city-states, and maintained meticulous records of his destructions.[16] Most of the major Sumerian cities were destroyed, and Sumerian human losses were enormous:[16][17] It appears that the city of Shuruppak was spared.[18]

| Sumerian casualties from the campaigns of Rimush[16] | ||||||

| Destroyed cities: | Adab and Zabala | Umma and KI.AN | Ur and Lagash | Kazallu | (Three battles in Sumer) | TOTAL |

| Killed | 15,718 | 8,900 | 8,049 | 12,052 | 11,322 | 56,041 |

| Captured and enslaved | 14,576 | 3,540 | 5,460 | 5,862 | _ | 29,438 |

| "Expelled and annihilated" | _ | 5,600 | 5,985 | _ | 14,100 | 25,685 |

Victory Stele of Rimush over Lagash

A Victory Stele in several fragments (three in total, Louvre Museum, AO 2678 for the relief and AO 2679 for the inscriptions, with possibly another fragment from the Yale Babylonian Collection YBC 2409)[21][22] has been attributed to Rimush on stylistic and epigraphical grounds.[22] One of the fragments mentions Akkad and Lagash.[19] The style is airy and the figures are more refined than those from the time of Sargon of Akkad.[23] One fragment in the main inscription probably contains parts of the name of Rimush himself.[22]

It is thought that the stele represents the defeat of Lagash by the troops of Akkad.[20] The prisoners depicted in the relief are visibly Mesopotamian, and their slaughtering at the hand of Akkadian soldiers is consistent with the known accounts of Rimush.[22][23] The stele was excavated in ancient Girsu, one of the main cities of the territory of Lagash.[19] The inscription describes the attribution of large plots of land from Lagash to the Akkadian nobility, following the victory.[23]

Campaigns against Elam and Marhashi

There are also records of victorious campaigns against Elam and Marhashi (Sumerian name for the Akkadian "Parahshum") in his 3rd year.[12][29][30] According to the account, troops from (Meluhha) also participated in the conflict:[12]

After the victorious campaigns of Rimush, under his successor Manishtushu, Elam would be ruled by Akkadian Military Governors, starting with Eshpum, and Pashime, on the Iranian coast, was ruled by an Akkadian Governor named Ilshu-rabi.[31] Upon his return from conquering Elam Rimush gave thanks to the deity of Nippur, Enlil, with 30 mana of gold, 3,600 mana of copper, and 360 slaves.[32]

"Rimuš, the king of the world, in battle over Abalgamash, king of Parahshum, was victorious. And Zahara[33] and Elam and Gupin and Meluḫḫa within Paraḫšum assembled for battle, but he (Rimush) was victorious and struck down 16,212 men and took 4,216 captives. Further, he captured Emahsini, King of Elam, and all the nobles of Elam. Further he captured Sidaga'u the general of Paraḫšum and Sargapi, general of Zahara, in between the cities of Awan and Susa, by the "Middle River". Further a burial mound at the site of the town he heaped up over them. Furthermore, the foundations of Paraḫšum from the country of Elam he tore out, and so Rimuš, king of the world, rules Elam, (as) the god Enlil had shown..."

Gallery

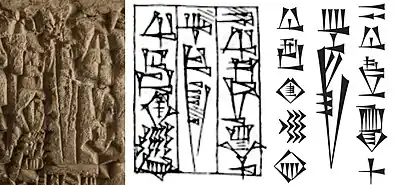

"Abalgamash, King of Marhashi" (𒀀𒁀𒀠𒂵𒈦 𒈗 𒁀𒊏𒄴𒋳𒆠 Abalgamash Lugal Paraahshum-ki) on one of the Rimush inscriptions (Louvre Museum, AO 5476)

"Abalgamash, King of Marhashi" (𒀀𒁀𒀠𒂵𒈦 𒈗 𒁀𒊏𒄴𒋳𒆠 Abalgamash Lugal Paraahshum-ki) on one of the Rimush inscriptions (Louvre Museum, AO 5476).jpg.webp) Prisoner of the Akkadian Empire, nude, fettered, drawn by nose ring, with pointed beard and vertical braid. Thought to depict a typical Marhashi.[35] 2350-2000 BC, Louvre Museum AO 5683.[20]

Prisoner of the Akkadian Empire, nude, fettered, drawn by nose ring, with pointed beard and vertical braid. Thought to depict a typical Marhashi.[35] 2350-2000 BC, Louvre Museum AO 5683.[20]

Artifacts in the name of Rimush

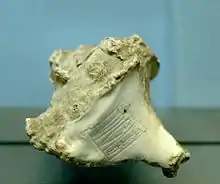

Vase in the name of "Rimush, King of Kish", albaster, Tello ancient Girsu.

Vase in the name of "Rimush, King of Kish", albaster, Tello ancient Girsu. Name of Rimush on an inscription.

Name of Rimush on an inscription..jpg.webp)

See also

References

- "Head of a ruler". www.metmuseum.org.

- B. R. Foster, The Age of Agade, Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia, London, New York 2016 ISBN 978-1138909755

- Helle, Sophus, "Enheduana’s World", Enheduana: The Complete Poems of the World's First Author, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 103-133, 2023

- Harris, Rivkah, "The Archive of the Sin Temple in Khafajah (Tutub)", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 31–58, 1955

- Ulla Koch-Westenholz (2000). Babylonian Liver Omens: The Chapters Manzazu, Padanu, and Pan Takalti of the Babylonian Extispicy Series Mainly from Assurbanipal's Library. Museum Tusculanum. p. 394.

- Samuel Noah Kramer (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45238-8.

- Mario Liverani (2002). "Reviewed Work: Mesopotamien. Akkade-Zeit und Ur III-Zeit. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 160/3 by Walther Sallaberger, Aage Westenholz, P. Attinger, M. Wäfler". Archiv für Orientforschung. 48/49: 180–181. JSTOR 41668552.

- Steinkeller, P., "An Ur III manuscript of the Sumerian King List", in: W. Sallaberger [e.a.] (ed.), Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien. Festschrift fü r Claus Wilcke. OBC 14. Wiesbaden, 267–29, 2003

- Thomas, Ariane. "The Akkadian Royal Image: On a Seated Statue of Manishtushu" Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 105, no. 1-2, 2015, pp. 86-117

- Who's Who in the Ancient Near East - Page 137; by Gwendolyn Leick

- "He wears a tufted garment, an indication that he is of high rank, possibly the king himself" in Art of the first cities : the third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 202.

- Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. Routledge. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- "Year Names of Rimush [CDLI Wiki]". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. Routledge. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- Crowe, D. (2014). War Crimes, Genocide, and Justice: A Global History. Springer. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-137-03701-5.

- Frahm, Eckart, and Elizabeth E. Payne, "Šuruppak under Rīmuš: A Rediscovered Inscription", Archiv Für Orientforschung, vol. 50, pp. 50–55, 2003

- Heuzey, Léon (1895). "Le nom d'Agadé sur un monument de Sirpourla". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 3 (4): 113–117. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23284246.

- Thomas, Ariane; Potts, Timothy (2020). Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-1-60606-649-2.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Foster, Benjamin R. (1985). "The Sargonic Victory Stele from Telloh". Iraq. 47: 15–30. doi:10.2307/4200229. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200229.

- Art of the first cities : the third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 202.

- "Musée du Louvre-Lens - Portail documentaire - Stèle de victoire du roi Rimush (?)". ressources.louvrelens.fr (in French).

- McKeon, John F. X. (1970). "An Akkadian Victory Stele". Boston Museum Bulletin. 68 (354): 235. ISSN 0006-7997. JSTOR 4171539.

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Frayne, Douglas (1993). Sargonic and Gutian Periods. pp. 55–56.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire. Routledge. p. 449. ISBN 978-1-134-15907-9.

- Potts, D. T. (2016). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-1-107-09469-7.

- Ratnagar, Shereen F., "Theorizing Bronze-Age Intercultural Trade : The Evidence of the Weights", Paléorient, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 79–92, 2003

- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: From the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. Taylor & Francis. p. 784. ISBN 978-0-415-39485-7.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Álvarez-Mon, Javier; Basello, Gian Pietro; Wicks, Yasmina (2018). The Elamite World. Routledge. p. 368, note 15. ISBN 9781317329831.

- THUREAU-DANGIN, F. (1911). "Notes Assyriologiques". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 8 (3): 138–141. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23284567.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)