Red

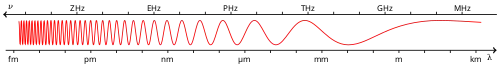

Red is the color at the long wavelength end of the visible spectrum of light, next to orange and opposite violet. It has a dominant wavelength of approximately 625–740 nanometres.[1] It is a primary color in the RGB color model and a secondary color (made from magenta and yellow) in the CMYK color model, and is the complementary color of cyan. Reds range from the brilliant yellow-tinged scarlet and vermillion to bluish-red crimson, and vary in shade from the pale red pink to the dark red burgundy.[2]

| Red | |

|---|---|

Clockwise, from top left: fresh strawberries; Northern cardinal; Magdalena Frąckowiak wearing a red dress at Paris Fashion Week; Honor guard of Chinese People's Liberation Army holding red flags; Cardinal Théodore-Adrien Sarr, Archbishop of Dakar. | |

| Spectral coordinates | |

| Wavelength | Approx. 625–740[1] nm |

| Frequency | ~480–400 THz |

| Hex triplet | #FF0000 |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (255, 0, 0) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (0°, 100%, 100%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (53, 179, 12°) |

| Source | X11 |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) H: Normalized to [0–100] (hundred) | |

Red pigment made from ochre was one of the first colors used in prehistoric art. The Ancient Egyptians and Mayans colored their faces red in ceremonies; Roman generals had their bodies colored red to celebrate victories. It was also an important color in China, where it was used to color early pottery and later the gates and walls of palaces.[3]: 60–61 In the Renaissance, the brilliant red costumes for the nobility and wealthy were dyed with kermes and cochineal. The 19th century brought the introduction of the first synthetic red dyes, which replaced the traditional dyes. Red became a symbolic color of communism and socialism; Soviet Russia adopted a red flag following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, until the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. Communist China adopted the red flag following the Chinese Revolution of 1949. It was adopted by North Vietnam in 1954, and by all of Vietnam in 1975.

Since red is the color of blood, it has historically been associated with sacrifice, danger, and courage. Modern surveys in Europe and the United States show red is also the color most commonly associated with heat, activity, passion, sexuality, anger, love, and joy. In China, India, and many other Asian countries it is the color symbolizing happiness and good fortune.[4]: 39–63

Shades and variations

Varieties of the color red may differ in hue, chroma (also called saturation, intensity, or colorfulness), or lightness (or value, tone, or brightness), or in two or three of these qualities. Variations in value are also called tints and shades, a tint being a red or other hue mixed with white, a shade being mixed with black. Four examples are shown below.

In science and nature

Seeing red

The human eye sees red when it looks at light with a wavelength between approximately 625 and 740 nanometers.[1] It is a primary color in the RGB color model and the light just past this range is called infrared, or below red, and cannot be seen by human eyes, although it can be sensed as heat.[7] In the language of optics, red is the color evoked by light that stimulates neither the S or the M (short and medium wavelength) cone cells of the retina, combined with a fading stimulation of the L (long-wavelength) cone cells.[8]

Primates can distinguish the full range of the colors of the spectrum visible to humans, but many kinds of mammals, such as dogs and cattle, have dichromacy, which means they can see blues and yellows, but cannot distinguish red and green (both are seen as gray). Bulls, for instance, cannot see the red color of the cape of a bullfighter, but they are agitated by its movement.[9] (See color vision).

One theory for why primates developed sensitivity to red is that it allowed ripe fruit to be distinguished from unripe fruit and inedible vegetation.[10] This may have driven further adaptations by species taking advantage of this new ability, such as the emergence of red faces.[11]

Red light is used to help adapt night vision in low-light or night time, as the rod cells in the human eye are not sensitive to red.[12][13]

In color theory and on a computer screen

In the RYB color model, which is the basis of traditional color theory, red is one of the three primary colors, along with blue and yellow. Painters in the Renaissance mixed red and blue to make violet: Cennino Cennini, in his 15th-century manual on painting, wrote, "If you want to make a lovely violet colour, take fine lac (red lake), ultramarine blue (the same amount of the one as of the other) with a binder"; he noted that it could also be made by mixing blue indigo and red hematite.[14]

In the CMY and CMYK color models, red is a secondary color subtractively mixed from magenta and yellow.

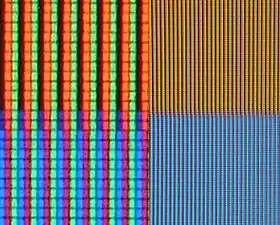

In the RGB color model, red, green and blue are additive primary colors. Red, green and blue light combined makes white light, and these three colors, combined in different mixtures, can produce nearly any other color. This principle is used to generate colors on such as computer monitors and televisions. For example, magenta on a computer screen is made by a similar formula to that used by Cennino Cennini in the Renaissance to make violet, but using additive colors and light instead of pigment: it is created by combining red and blue light at equal intensity on a black screen. Violet is made on a computer screen in a similar way, but with a greater amount of blue light and less red light.[15]

In a traditional color wheel from 1708, red, yellow and blue are primary colors. Red and yellow make orange; red and blue make violet.

In a traditional color wheel from 1708, red, yellow and blue are primary colors. Red and yellow make orange; red and blue make violet. In modern color theory, red, green and blue are the additive primary colors, and together they make white. A combination of red, green and blue light in varying proportions makes all the colors on your computer screen and television screen.

In modern color theory, red, green and blue are the additive primary colors, and together they make white. A combination of red, green and blue light in varying proportions makes all the colors on your computer screen and television screen. Tiny Red, green and blue sub-pixels (enlarged on left side of image) create the colors you see on your computer screen and TV.

Tiny Red, green and blue sub-pixels (enlarged on left side of image) create the colors you see on your computer screen and TV.

Color of sunset

As a ray of white sunlight travels through the atmosphere to the eye, some of the colors are scattered out of the beam by air molecules and airborne particles due to Rayleigh scattering, changing the final color of the beam that is seen. Colors with a shorter wavelength, such as blue and green, scatter more strongly, and are removed from the light that finally reaches the eye.[16] At sunrise and sunset, when the path of the sunlight through the atmosphere to the eye is longest, the blue and green components are removed almost completely, leaving the longer wavelength orange and red light. The remaining reddened sunlight can also be scattered by cloud droplets and other relatively large particles, which give the sky above the horizon its red glow.[17]

Lasers

Lasers emitting in the red region of the spectrum have been available since the invention of the ruby laser in 1960. In 1962 the red helium–neon laser was invented,[18] and these two types of lasers were widely used in many scientific applications including holography, and in education. Red helium–neon lasers were used commercially in LaserDisc players. The use of red laser diodes became widespread with the commercial success of modern DVD players, which use a 660 nm laser diode technology. Today, red and red-orange laser diodes are widely available to the public in the form of extremely inexpensive laser pointers. Portable, high-powered versions are also available for various applications.[19] More recently, 671 nm diode-pumped solid state (DPSS) lasers have been introduced to the market for all-DPSS laser display systems, particle image velocimetry, Raman spectroscopy, and holography.[20]

Red's wavelength has been an important factor in laser technologies; red lasers, used in early compact disc technologies, are being replaced by blue lasers, as red's longer wavelength causes the laser's recordings to take up more space on the disc than would blue-laser recordings.[21]

Astronomy

- Mars is called the Red Planet because of the reddish color imparted to its surface by the abundant iron oxide present there.[22]

- Astronomical objects that are moving away from the observer exhibit a Doppler red shift.

- Jupiter's surface displays a Great Red Spot caused by an oval-shaped mega storm south of the planet's equator.[23]

- Red giants are stars that have exhausted the supply of hydrogen in their cores and switched to thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen in a shell that surrounds its core. They have radii tens to hundreds of times larger than that of the Sun. However, their outer envelope is much lower in temperature, giving them an orange hue. Despite the lower energy density of their envelope, red giants are many times more luminous than the Sun due to their large size.

- Red supergiants like Antares, Betelgeuse, VY Canis Majoris and UY Scuti, one of the biggest stars in the Universe, are the biggest variety of red giants. They are huge in size, with radii 200 to 2600 times greater than the Sun, but relatively cool in temperature (3000–4500 K), causing their distinct red tint. Because they are shrinking rapidly in size, they are surrounded by an envelope or skin much bigger than the star itself. The envelope of Betelgeuse is 250 times bigger than the star inside.

- A red dwarf is a small and relatively cool star, which has a mass of less than half that of the Sun and a surface temperature of less than 4,000 K. Red dwarfs are by far the most common type of star in the Galaxy, but due to their low luminosity, from Earth, none are visible to the naked eye.[24]

- Interstellar reddening is caused by the extinction of radiation by dust and gas

Mars appears to be red because of iron oxide on its surface.

Mars appears to be red because of iron oxide on its surface.

Artist's impression of a red dwarf, a small, relatively cool star that appears red due to its temperature

Artist's impression of a red dwarf, a small, relatively cool star that appears red due to its temperature

Pigments and dyes

Red ochre cliffs near Roussillon in France. Red ochre is composed of clay tinted with hematite. Ochre was the first pigment used by man in prehistoric cave paintings.

Red ochre cliffs near Roussillon in France. Red ochre is composed of clay tinted with hematite. Ochre was the first pigment used by man in prehistoric cave paintings. Vermilion pigment, made from cinnabar. This was the pigment used in the murals of Pompeii and to color Chinese lacquerware beginning in the Song dynasty.

Vermilion pigment, made from cinnabar. This was the pigment used in the murals of Pompeii and to color Chinese lacquerware beginning in the Song dynasty. Red lead, also known as minium, has been used since the time of the ancient Greeks. Chemically it is known as lead tetroxide. The Romans prepared it by the roasting of lead white pigment. It was commonly used in the Middle Ages for the headings and decoration of illuminated manuscripts.

Red lead, also known as minium, has been used since the time of the ancient Greeks. Chemically it is known as lead tetroxide. The Romans prepared it by the roasting of lead white pigment. It was commonly used in the Middle Ages for the headings and decoration of illuminated manuscripts. The roots of the Rubia tinctorum, or madder plant, produced the most common red dye used from ancient times until the 19th century.

The roots of the Rubia tinctorum, or madder plant, produced the most common red dye used from ancient times until the 19th century. Alizarin was the first synthetic red dye, created by German chemists in 1868. It duplicated the colorant in the madder plant, but was cheaper and longer lasting. After its introduction, the production of natural dyes from the madder plant virtually ceased.

Alizarin was the first synthetic red dye, created by German chemists in 1868. It duplicated the colorant in the madder plant, but was cheaper and longer lasting. After its introduction, the production of natural dyes from the madder plant virtually ceased.

Food coloring

The most common synthetic food coloring today is Allura Red AC, a red azo dye that goes by several names including: Allura Red, Food Red 17, C.I. 16035, FD&C Red 40,[25][26] It was originally manufactured from coal tar, but now is mostly made from petroleum.[27]

In Europe, Allura Red AC is not recommended for consumption by children. It is banned in Denmark, Belgium, France and Switzerland, and was also banned in Sweden until the country joined the European Union in 1994.[26] The European Union approves Allura Red AC as a food colorant, but EU countries' local laws banning food colorants are preserved.[28]

In the United States, Allura Red AC is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in cosmetics, drugs, and food. It is used in some tattoo inks and is used in many products, such as soft drinks, children's medications, and cotton candy. On June 30, 2010, the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) called for the FDA to ban Red 40.[29]

Because of public concerns about possible health risks associated with synthetic dyes, many companies have switched to using natural pigments such as carmine, made from crushing the tiny female cochineal insect. This insect, originating in Mexico and Central America, was used to make the brilliant scarlet dyes of the European Renaissance.

Autumn leaves

The red of autumn leaves is produced by pigments called anthocyanins. They are not present in the leaf throughout the growing season, but are actively produced towards the end of summer.[30] They develop in late summer in the sap of the cells of the leaf, and this development is the result of complex interactions of many influences—both inside and outside the plant. Their formation depends on the breakdown of sugars in the presence of bright light as the level of phosphate in the leaf is reduced.[31]

During the summer growing season, phosphate is at a high level. It has a vital role in the breakdown of the sugars manufactured by chlorophyll. But in the fall, phosphate, along with the other chemicals and nutrients, moves out of the leaf into the stem of the plant. When this happens, the sugar-breakdown process changes, leading to the production of anthocyanin pigments. The brighter the light during this period, the greater the production of anthocyanins and the more brilliant the resulting color display. When the days of autumn are bright and cool, and the nights are chilly but not freezing, the brightest colorations usually develop.

Anthocyanins temporarily color the edges of some of the very young leaves as they unfold from the buds in early spring. They also give the familiar color to such common fruits as cranberries, red apples, blueberries, cherries, raspberries, and plums.

Anthocyanins are present in about 10% of tree species in temperate regions, although in certain areas—a famous example being New England—up to 70% of tree species may produce the pigment.[30] In autumn forests they appear vivid in the maples, oaks, sourwood, sweetgums, dogwoods, tupelos, cherry trees and persimmons. These same pigments often combine with the carotenoids' colors to create the deeper orange, fiery reds, and bronzes typical of many hardwood species. (See Autumn leaf color).

Blood and other reds in nature

Oxygenated blood is red due to the presence of oxygenated hemoglobin that contains iron molecules, with the iron components reflecting red light.[32][33] Red meat gets its color from the iron found in the myoglobin and hemoglobin in the muscles and residual blood.[34]

Plants like apples, strawberries, cherries, tomatoes, peppers, and pomegranates are often colored by forms of carotenoids, red pigments that also assist photosynthesis.[35]

Red blood cell agar. Blood appears red due to the iron molecules in blood cells.

Red blood cell agar. Blood appears red due to the iron molecules in blood cells. A red setter or Irish setter

A red setter or Irish setter_-British_Wildlife_Centre-8.jpg.webp) A pair of European red foxes

A pair of European red foxes The European robin or robin redbreast

The European robin or robin redbreast

Hair color

Red hair occurs naturally on approximately 1–2% of the human population.[36] It occurs more frequently (2–6%) in people of northern or western European ancestry, and less frequently in other populations. Red hair appears in people with two copies of a recessive gene on chromosome 16 which causes a mutation in the MC1R protein.[37]

Red hair varies from a deep burgundy through burnt orange to bright copper. It is characterized by high levels of the reddish pigment pheomelanin (which also accounts for the red color of the lips) and relatively low levels of the dark pigment eumelanin. The term "redhead" (originally redd hede) has been in use since at least 1510.[38]

In animal and human behavior

Red is associated with dominance in a number of animal species.[39] For example, in mandrills, red coloration of the face is greatest in alpha males, increasingly less prominent in lower ranking subordinates, and directly correlated with levels of testosterone.[40] Red can also affect the perception of dominance by others, leading to significant differences in mortality, reproductive success and parental investment between individuals displaying red and those not.[41] In humans, wearing red has been linked with increased performance in competitions, including professional sport[42][43] and multiplayer video games.[44] Controlled tests have demonstrated that wearing red does not increase performance or levels of testosterone during exercise, so the effect is likely to be produced by perceived rather than actual performance.[45] Judges of tae kwon do have been shown to favor competitors wearing red protective gear over blue,[46] and, when asked, a significant majority of people say that red abstract shapes are more "dominant", "aggressive", and "likely to win a physical competition" than blue shapes.[39] In contrast to its positive effect in physical competition and dominance behavior, exposure to red decreases performance in cognitive tasks[47] and elicits aversion in psychological tests where subjects are placed in an "achievement" context (e.g. taking an IQ test).[48]

History and art

In prehistory and the ancient world

Bison in red ochre in the Cave of Altamira, Spain, from upper Paleolithic era (36,000 BC)

Bison in red ochre in the Cave of Altamira, Spain, from upper Paleolithic era (36,000 BC)

Roman wall painting showing a dye shop, Pompeii (40 BC)

Roman wall painting showing a dye shop, Pompeii (40 BC)

Inside cave 13B at Pinnacle Point, an archeological site found on the coast of South Africa, paleoanthropologists in 2000 found evidence that, between 170,000 and 40,000 years ago, Late Stone Age people were scraping and grinding ochre, a clay colored red by iron oxide, probably with the intention of using it to color their bodies.[49]

Red hematite powder was also found scattered around the remains at a grave site in a Zhoukoudian cave complex near Beijing. The site has evidence of habitation as early as 700,000 years ago. The hematite might have been used to symbolize blood in an offering to the dead.[3]: 4

Red, black and white were the first colors used by artists in the Upper Paleolithic age, probably because natural pigments such as red ochre and iron oxide were readily available where early people lived. Madder, a plant whose root could be made into a red dye, grew widely in Europe, Africa and Asia.[50] The cave of Altamira in Spain has a painting of a bison colored with red ochre that dates to between 15,000 and 16,500 BC.[51]

A red dye called Kermes was made beginning in the Neolithic Period by drying and then crushing the bodies of the females of a tiny scale insect in the genus Kermes, primarily Kermes vermilio. The insects live on the sap of certain trees, especially Kermes oak trees near the Mediterranean region. Jars of kermes have been found in a Neolithic cave-burial at Adaoutse, Bouches-du-Rhône.[52]: 230–31 Kermes from oak trees was later used by Romans, who imported it from Spain. A different variety of dye was made from Porphyrophora hamelii (Armenian cochineal) scale insects that lived on the roots and stems of certain herbs. It was mentioned in texts as early as the 8th century BC, and it was used by the ancient Assyrians and Persians.[53]: 45

Red hematite powder was also found scattered around the remains at a grave site in a Zhoukoudian cave complex near Beijing. The site has evidence of habitation as early as 700,000 years ago. The hematite might have been used to symbolize blood in an offering to the dead.[3]: 4

In ancient Egypt, red was associated with life, health, and victory. Egyptians would color themselves with red ochre during celebrations.[54] Egyptian women used red ochre as a cosmetic to redden cheeks and lips[55] and also used henna to color their hair and paint their nails.[56]

The ancient Romans wore togas with red stripes on holidays, and the bride at a wedding wore a red shawl, called a flammeum.[4]: 46 Red was used to color statues and the skin of gladiators. Red was also the color associated with army; Roman soldiers wore red tunics, and officers wore a cloak called a paludamentum which, depending upon the quality of the dye, could be crimson, scarlet or purple. In Roman mythology red is associated with the god of war, Mars.[57] The vexilloid of the Roman Empire had a red background with the letters SPQR in gold. A Roman general receiving a triumph had his entire body painted red in honor of his achievement.[58]

The Romans liked bright colors, and many Roman villas were decorated with vivid red murals. The pigment used for many of the murals was called vermilion, and it came from the mineral cinnabar, a common ore of mercury. It was one of the finest reds of ancient times – the paintings have retained their brightness for more than twenty centuries. The source of cinnabar for the Romans was a group of mines near Almadén, southwest of Madrid, in Spain. Working in the mines was extremely dangerous, since mercury is highly toxic; the miners were slaves or prisoners, and being sent to the cinnabar mines was a virtual death sentence.[59]

The Middle Ages

Roman Catholic Popes wear red as the symbol of the blood of Christ. This is Pope Innocent III, in about 1219.

Roman Catholic Popes wear red as the symbol of the blood of Christ. This is Pope Innocent III, in about 1219..jpg.webp) Red was the traditional color of martyrs. A Russian icon of Saint George (14th c.).

Red was the traditional color of martyrs. A Russian icon of Saint George (14th c.). THe colour of majesty - portrait of Charlemagne, King of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor, Netherlands (14th c.)

THe colour of majesty - portrait of Charlemagne, King of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor, Netherlands (14th c.)

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, red was adopted as a color of majesty and authority by the Byzantine Empire, and the princes of Europe. It also played an important part in the rituals of the Roman Catholic Church, symbolizing the blood of Christ and the Christian martyrs.[60][61]

In Western Europe, Emperor Charlemagne painted his palace red as a very visible symbol of his authority, and wore red shoes at his coronation.[53]: 36–37 Kings, princes and, beginning in 1295, Roman Catholic cardinals began to wear red colored habitus. When Abbe Suger rebuilt Saint Denis Basilica outside Paris in the early 12th century, he added stained glass windows colored blue cobalt glass and red glass tinted with copper. Together they flooded the basilica with a mystical light. Soon stained glass windows were being added to cathedrals all across France, England and Germany. In medieval painting red was used to attract attention to the most important figures; both Christ and the Virgin Mary were commonly painted wearing red mantles.

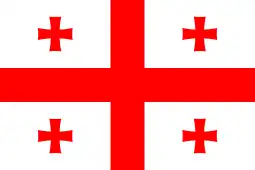

In western countries red is a symbol of martyrs and sacrifice, particularly because of its association with blood.[57] Beginning in the Middle Ages, the Pope and Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church wore red to symbolize the blood of Christ and the Christian martyrs. The banner of the Christian soldiers in the First Crusade was a red cross on a white field, the St. George's Cross. According to Christian tradition, Saint George was a Roman soldier who was a member of the guards of the Emperor Diocletian, who refused to renounce his Christian faith and was martyred. The Saint George's Cross became the Flag of England in the 16th century, and now is part of the Union Flag of the United Kingdom, as well as the Flag of the Republic of Georgia.[53]: 36

Renaissance

The young Queen Elizabeth I (here in about 1563)

The young Queen Elizabeth I (here in about 1563) The Wedding Dance (1566), by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

The Wedding Dance (1566), by Pieter Bruegel the Elder The Girl with the Wine Glass, by Johannes Vermeer (1659–60)

The Girl with the Wine Glass, by Johannes Vermeer (1659–60) Princess Anne of Denmark (later Queen Anne of Great Britain) (1685)

Princess Anne of Denmark (later Queen Anne of Great Britain) (1685)

In Renaissance painting, red was used to draw the attention of the viewer; it was often used as the color of the cloak or costume of Christ, the Virgin Mary, or another central figure.

In Venice, Titian was the master of fine reds, particularly vermilion; he used many layers of pigment mixed with a semi-transparent glaze, which let the light pass through, to create a more luminous color. The figures of God, the Virgin Mary and two apostles are highlighted by their vermilion red costumes.

Queen Elizabeth I of England liked to wear bright reds, before she adopted the more sober image of the "Virgin Queen".

Red costumes were not limited to the upper classes. In Renaissance Flanders, people of all social classes wore red at celebrations. One such celebration was captured in The Wedding Dance (1566) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

The painter Johannes Vermeer skilfully used different shades and tints of vermilion to paint the red skirt in The Girl with the Wine Glass, then glazed it with madder lake to make a more luminous color.

Reds from the New World

A native of Central America collecting cochineal insects from a cactus to make red dye (1777)

A native of Central America collecting cochineal insects from a cactus to make red dye (1777)

In Latin America, the Aztec people, the Paracas culture and other societies used cochineal, a vivid scarlet dye made from insects. From the 16th until the 19th century, cochineal became a highly profitable export from Spanish Mexico to Europe.

18th to 20th century

_-_Miguel_Ant%C3%B3nio_do_Amaral.png.webp) King Joseph I of Portugal (1773)

King Joseph I of Portugal (1773) The Brazilian imperial family (1857)

The Brazilian imperial family (1857) King Edward VII of the United Kingdom (1901)

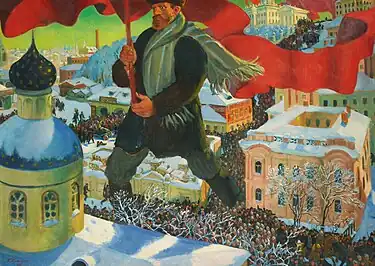

King Edward VII of the United Kingdom (1901) Red flag of the Bolsheviks, by Boris Kustodiev (1920)

Red flag of the Bolsheviks, by Boris Kustodiev (1920) Chinese honour guard, Beijing, 2007

Chinese honour guard, Beijing, 2007

In the 18th century, red began to take on a new identity as the colour of resistance and revolution. It was already associated with blood, and with danger; a red flag hoisted before a battle meant that no prisoners would be taken. In 1793-94, red became the colour of the French Revolution. A red Phrygian cap, or "liberty cap", was part of the uniform of the sans-culottes, the most militant faction of the revolutionaries.[62]

In the late 18th century, during a strike English dock workers carried red flags, and it thereafter became closely associated with the new labour movement, and later with the Labour Party in the United Kingdom, founded in 1900.

In Paris in 1832, a red flag was carried by working-class demonstrators in the failed June Rebellion, an event immortalised in Les Misérables), and later in the 1848 French Revolution.[63] The red flag was proposed as the new national French flag during the 1848 revolution, but was rejected by at the urging of the poet and statesman Alphonse Lamartine in favour of the tricolour flag. It appeared again as the flag of the short-lived Paris Commune in 1871. It was then adopted by Karl Marx and the new European movements of socialism and communism. Soviet Russia adopted a red flag following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. Communist China adopted the red flag following the Chinese Revolution of 1949. It was adopted by North Vietnam in 1954, and by all of Vietnam in 1975.

Symbolism

Courage and sacrifice

Surveys show that red is the color most associated with courage.[4]: 43 In western countries red is a symbol of martyrs and sacrifice, particularly because of its association with blood.[57] Beginning in the Middle Ages, the Pope and Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church wore red to symbolize the blood of Christ and the Christian martyrs. The banner of the Christian soldiers in the First Crusade was a red cross on a white field, the St. George's Cross. According to Christian tradition, Saint George was a Roman soldier who was a member of the guards of the Emperor Diocletian, who refused to renounce his Christian faith and was martyred. The Saint George's Cross became the Flag of England in the 16th century, and now is part of the Union Flag of the United Kingdom, as well as the Flag of the Republic of Georgia.[53]: 36

Robert Gibb's 1881 painting, The Thin Red Line, depicting The Thin Red Line at the Battle of Balaclava (1854), when a line of the Scottish Highland infantry repulsed a Russian cavalry charge. The name was given by the British press as a symbol of courage against the odds.

Robert Gibb's 1881 painting, The Thin Red Line, depicting The Thin Red Line at the Battle of Balaclava (1854), when a line of the Scottish Highland infantry repulsed a Russian cavalry charge. The name was given by the British press as a symbol of courage against the odds. The red poppy flower is worn on Remembrance Day in Commonwealth countries to honor soldiers who died in the First World War.

The red poppy flower is worn on Remembrance Day in Commonwealth countries to honor soldiers who died in the First World War.

Hatred, anger, aggression, passion, heat and war

While red is the color most associated with love, it also the color most frequently associated with hatred, anger, aggression and war. People who are angry are said to "see red." Red is the color most commonly associated with passion and heat. In ancient Rome, red was the color of Mars, the god of war—the planet Mars was named for him because of its red color.[4]: 42, 53

Warning and danger

Red is the traditional color of warning and danger, and is therefore often used on flags. In the Middle Ages up through the French Revolution, a red flag shown in warfare indicated the intent to take no prisoners.[64][65] Similarly, a red flag hoisted by a pirate ship meant no mercy would be shown to their target.[66][67] In Britain, in the early days of motoring, motor cars had to follow a man with a red flag who would warn horse-drawn vehicles, before the Locomotives on Highways Act 1896 abolished this law.[68] In automobile races, the red flag is raised if there is danger to the drivers.[69] In international football, a player who has made a serious violation of the rules is shown a red penalty card and ejected from the game.[70]

Several studies have indicated that red carries the strongest reaction of all the colors, with the level of reaction decreasing gradually with the colors orange, yellow, and white, respectively.[71][72] For this reason, red is generally used as the highest level of warning, such as threat level of terrorist attack in the United States. In fact, teachers at a primary school in the UK have been told not to mark children's work in red ink because it encourages a "negative approach".[73]

Red is the international color of stop signs and stop lights on highways and intersections. It was standardized as the international color at the Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals of 1968. It was chosen partly because red is the brightest color in daytime (next to orange), though it is less visible at twilight, when green is the most visible color. Red also stands out more clearly against a cool natural backdrop of blue sky, green trees or gray buildings. But it was mostly chosen as the color for stoplights and stop signs because of its universal association with danger and warning.[4]: 54 The 1968 Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals of 1968 uses red color also for the margin of danger warning sign, give way signs and prohibitory signs, following the previous German-type signage (established by Verordnung über Warnungstafeln für den Kraftfahrzeugverkehr in 1927).

The standard international stop sign, following the Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals of 1968

The standard international stop sign, following the Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals of 1968.jpg.webp) A footballer is shown a red card and ejected from a soccer match.

A footballer is shown a red card and ejected from a soccer match. A red Chinese typhoon alert sign

A red Chinese typhoon alert sign Red is the color of a severe terrorist threat level in the United States, under the Homeland Security Advisory System.

Red is the color of a severe terrorist threat level in the United States, under the Homeland Security Advisory System. Red is the color of a severe fire danger in Australia; new black/red stripes are an even more catastrophic hazard.

Red is the color of a severe fire danger in Australia; new black/red stripes are an even more catastrophic hazard.

The color that attracts attention

Red is the color that most attracts attention. Surveys show it is the color most frequently associated with visibility, proximity, and extroverts.[74] It is also the color most associated with dynamism and activity.[4]: 48, 58

Red is used in modern fashion much as it was used in Medieval painting; to attract the eyes of the viewer to the person who is supposed to be the center of attention. People wearing red seem to be closer than those dressed in other colors, even if they are actually the same distance away.[4]: 48, 58 Monarchs, wives of presidential candidates and other celebrities often wear red to be visible from a distance in a crowd. It is also commonly worn by lifeguards and others whose job requires them to be easily found.[75][76]

Because red attracts attention, it is frequently used in advertising, though studies show that people are less likely to read something printed in red because they know it is advertising, and because it is more difficult visually to read than black and white text.[4]: 60

Seduction, sexuality and sin

Red by a large margin is the color most commonly associated with seduction, sexuality, eroticism and immorality, possibly because of its close connection with passion and with danger.[4]: 55

Red was long seen as having a dark side, particularly in Christian theology. It was associated with sexual passion, anger, sin, and the devil.[77][78] In the Old Testament of the Bible, the Book of Isaiah said: "Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be white as snow."[79] In the New Testament, in the Book of Revelation, the Antichrist appears as a red monster, ridden by a woman dressed in scarlet, known as the Whore of Babylon.[80]

Satan is often depicted as colored red and/or wearing a red costume in both iconography and popular culture.[78][81] By the 20th century, the devil in red had become a folk character in legends and stories. The devil in red appears more often in cartoons and movies than in religious art.

In 17th-century New England, red was associated with adultery. In the 1850 novel by Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter, set in a Puritan New England community, a woman is punished for adultery with ostracism, her sin represented by a red letter 'A' sewn onto her clothes.[82][78]

Red is still commonly associated with prostitution. At various points in history, prostitutes were required to wear red to announce their profession.[78] Houses of prostitution displayed a red light. Beginning in the early 20th century, houses of prostitution were allowed only in certain specified neighborhoods, which became known as red-light districts. Large red-light districts are found today in Bangkok and Amsterdam.[83][84]

In both Christian and Hebrew tradition, red is also sometimes associated with murder or guilt, with "having blood on one's hands", or "being caught red-handed.[85]

.jpg.webp) The Whore of Babylon, depicted in a 14th-century French illuminated manuscript. The woman appears attractive, but is wearing red under her blue garment.

The Whore of Babylon, depicted in a 14th-century French illuminated manuscript. The woman appears attractive, but is wearing red under her blue garment. Reine de joie, (Queen of Joy), a book cover illustration by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1892) about a Paris prostitute

Reine de joie, (Queen of Joy), a book cover illustration by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1892) about a Paris prostitute Sheet music for "At the Devil's Ball", by Irving Berlin, United States, 1915

Sheet music for "At the Devil's Ball", by Irving Berlin, United States, 1915 The red-light district in Amsterdam (2003). Red is the sex industry's preferred color in many cultures, due to being strongly associated with passion, love and sexuality.[4]: 39–63

The red-light district in Amsterdam (2003). Red is the sex industry's preferred color in many cultures, due to being strongly associated with passion, love and sexuality.[4]: 39–63.jpg.webp) Red lipstick has been worn by women as a cosmetic since ancient times. It was worn by Cleopatra, Queen Elizabeth I, and film stars such as Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe.

Red lipstick has been worn by women as a cosmetic since ancient times. It was worn by Cleopatra, Queen Elizabeth I, and film stars such as Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe.

In religion

- In Christianity, red is associated with the blood of Christ and the sacrifice of martyrs. In the Roman Catholic Church it is also associated with pentecost and the Holy Spirit. Since 1295, it is the color worn by Cardinals, the senior clergy of the Roman Catholic Church. Red is the liturgical color for the feasts of martyrs, representing the blood of those who suffered death for their faith. It is sometimes used as the liturgical color for Holy Week, including Palm Sunday and Good Friday, although this is a modern (20th-century) development. In Catholic practice, it is also the liturgical color used to commemorate the Holy Spirit (for this reason it is worn at Pentecost and during Confirmation masses). Because of its association with martyrdom and the Spirit, it is also the color used to commemorate saints who were martyred, such as St. George and all the Apostles (except for the Apostle St. John, who was not martyred, where white is used). As such, it is used to commemorate bishops, who are the successors of the Apostles (for this reason, when funeral masses are held for bishops, cardinals, or popes, red is used instead of the white that would ordinarily be used).

- In Buddhism, red is one of the five colors which are said to have emanated from the Buddha when he attained enlightenment, or nirvana. It is particularly associated with the benefits of the practice of Buddhism; achievement, wisdom, virtue, fortune and dignity. It was also believed to have the power to resist evil. In China red was commonly used for the walls, pillars, and gates of temples.

- In the Shinto religion of Japan, the gateways of temples, called torii, are traditionally painted vermilion red and black. The torii symbolizes the passage from the profane world to a sacred place. The bridges in the gardens of Japanese temples are also painted red (and usually only temple bridges are red, not bridges in ordinary gardens), since they are also passages to sacred places. Red was also considered a color which could expel evil and disease.

- In Taoism, red is sometimes used to symbolize yang.[86]

- In Chinese folk religion, red is also sometimes used to symbolize yang in the context of the creator Pangu, who hatched out of a cosmic egg colored like a taijitu.[87] Some art of Pangu colored yang as red.[87]

Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church at the funeral of Pope John Paul II

Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church at the funeral of Pope John Paul II

.jpg.webp)

Military uses

Red uniform

The red military uniform was adopted by the English Parliament's New Model Army in 1645, and was still worn as a dress uniform by the British Army until the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. Ordinary soldiers wore red coats dyed with madder, while officers wore scarlet coats dyed with the more expensive cochineal.[53]: 168–69 This led to British soldiers being known as red coats.

In the modern British army, scarlet is still worn by the Foot Guards, the Life Guards, and by some regimental bands or drummers for ceremonial purposes. Officers and NCOs of those regiments which previously wore red retain scarlet as the color of their "mess" or formal evening jackets. The Royal Gibraltar Regiment has a scarlet tunic in its winter dress.

Scarlet is worn for some full dress, military band or mess uniforms in the modern armies of a number of the countries that made up the former British Empire. These include the Australian, Jamaican, New Zealand, Fijian, Canadian, Kenyan, Ghanaian, Indian, Singaporean, Sri Lankan and Pakistani armies.[88]

The musicians of the United States Marine Corps Band wear red, following an 18th-century military tradition that the uniforms of band members are the reverse of the uniforms of the other soldiers in their unit. Since the US Marine uniform is blue with red facings, the band wears the reverse.

Red Serge is the uniform of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, created in 1873 as the North-West Mounted Police, and given its present name in 1920. The uniform was adapted from the tunic of the British Army. Cadets at the Royal Military College of Canada also wear red dress uniforms.

The Brazilian Marine Corps wears a red dress uniform.

Officer and soldier of the British Army, 1815

Officer and soldier of the British Army, 1815 The scarlet uniform of the National Guards Unit of Bulgaria

The scarlet uniform of the National Guards Unit of Bulgaria Musicians of the United States Marine Corps Band

Musicians of the United States Marine Corps Band Officer of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

Officer of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police The Brazilian Marine Corps wears a dress uniform called A Garança.

The Brazilian Marine Corps wears a dress uniform called A Garança. Soldiers of the Rajput Regiment of the Indian Army

Soldiers of the Rajput Regiment of the Indian Army

NATO Military Symbols for Land Based Systems uses red to denote hostile forces, hence the terms "red team" and "Red Cell" to denote challengers during exercises.[89]

In sports

The first known team sport to feature red uniforms was chariot racing during the late Roman Empire. The earliest races were between two chariots, one driver wearing red, the other white. Later, the number of teams was increased to four, including drivers in light green and sky blue. Twenty-five races were run in a day, with a total of one hundred chariots participating.[90]

Today many sports teams throughout the world feature red on their uniforms. Along with blue, red is the most commonly used non-white color in sports. Numerous national sports teams wear red, often through association with their national flags. A few of these teams feature the color as part of their nickname such as Spain (with their association football (soccer) national team nicknamed La Furia Roja or "The Red Fury") and Belgium (whose football team bears the nickname Rode Duivels or "Red Devils").

In club association football (soccer), red is a commonly used color throughout the world. A number of teams' nicknames feature the color. A red penalty card is issued to a player who commits a serious infraction: the player is immediately disqualified from further play and his team must continue with one fewer player for the game's duration.

Rosso Corsa is the red international motor racing color of cars entered by teams from Italy. Since the 1920s Italian race cars of Alfa Romeo, Maserati, Lancia, and later Ferrari and Abarth have been painted with a color known as rosso corsa ("racing red"). National colors were mostly replaced in Formula One by commercial sponsor liveries in 1968, but unlike most other teams, Ferrari always kept the traditional red, although the shade of the color varies.

The color is commonly used for professional sports teams in Canada and the United States with eleven Major League Baseball teams, eleven National Hockey League teams, seven National Football League teams and eleven National Basketball Association teams prominently featuring some shade of the color. The color is also featured in the league logos of Major League Baseball, the National Football League and the National Basketball Association.[91] In the National Football League, a red flag is thrown by the head coach to challenge a referee's decision during the game. During the 1950s when red was strongly associated with communism in the United States, the modern Cincinnati Reds team was known as the "Redlegs" and the term was used on baseball cards. After the red scare faded, the team was known as the "Reds" again.[92]

In boxing, red is often the color used on a fighter's gloves. George Foreman wore the same red trunks he used during his loss to Muhammad Ali when he defeated Michael Moorer 20 years later to regain the title he lost. Boxers named or nicknamed "red" include Red Burman, Ernie "Red" Lopez, and his brother Danny "Little Red" Lopez.

Ancient Roman mosaic of the winner of a chariot race, wearing the colors of the red team

Ancient Roman mosaic of the winner of a chariot race, wearing the colors of the red team Both the Cleveland Indians and the Boston Red Sox wear red.

Both the Cleveland Indians and the Boston Red Sox wear red. In martial arts, a red belt shows a high degree of proficiency, second only, in some schools, to the black belt.

In martial arts, a red belt shows a high degree of proficiency, second only, in some schools, to the black belt. An Alfa Romeo Sports Racing car in 1977, painted Rosso Corsa ("racing red"), the traditional racing color of Italy from the 1920s until the late 1960s.

An Alfa Romeo Sports Racing car in 1977, painted Rosso Corsa ("racing red"), the traditional racing color of Italy from the 1920s until the late 1960s.

On flags

Red is the most common color found in national flags, found on the flags of 77 percent of the 210 countries listed as independent in 2016; far ahead of white (58 percent); green (40 percent) and blue (37 percent).[93] The British flag bears the colors red, white and blue; it includes the cross of Saint George, patron saint of England, and the saltire of Saint Patrick, patron saint of Ireland, both of which are red on white.[94]: 10 The flag of the United States bears the colors of Britain,[95] the colors of the French tricolore include red as part of the old Paris coat of arms, and other countries' flags, such as those of Australia, New Zealand, and Fiji, carry a small inset of the British flag in memory of their ties to that country.[94]: 13–20 Many former colonies of Spain, such as Mexico, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, Puerto Rico and Venezuela, also feature red-one of the colors of the Spanish flag-on their own banners. Red flags are also used to symbolize storms, bad water conditions, and many other dangers.

The red on the flag of Nepal represents the floral emblem of the country, the rhododendron.

Red, blue, and white are also the Pan-Slavic colors adopted by the Slavic solidarity movement of the late nineteenth century. Initially these were the colors of the Russian flag; as the Slavic movement grew, they were adopted by other Slavic peoples including Slovaks, Slovenes, and Serbs. The flags of the Czech Republic and Poland use red for historic heraldic reasons (see Coat of arms of Poland and Coat of arms of the Czech Republic) & not due to Pan-Slavic connotations. In 2004 Georgia adopted a new white flag, which consists of four small and one big red cross in the middle touching all four sides.

Red, white, and black were the colors of the German Empire from 1870 to 1918, and as such they came to be associated with German nationalism. In the 1920s they were adopted as the colors of the Nazi flag. In Mein Kampf, Hitler explained that they were "revered colors expressive of our homage to the glorious past." The red part of the flag was also chosen to attract attention – Hitler wrote: "the new flag ... should prove effective as a large poster" because "in hundreds of thousands of cases a really striking emblem may be the first cause of awakening interest in a movement." The red also symbolized the social program of the Nazis, aimed at German workers.[96] Several designs by a number of different authors were considered, but the one adopted in the end was Hitler's personal design.[97]

Red, white, green and black are the colors of Pan-Arabism and are used by many Arab countries.[98]

Red, gold, green, and black are the colors of Pan-Africanism. Several African countries thus use the color on their flags, including South Africa, Ghana, Senegal, Mali, Ethiopia, Togo, Guinea, Benin, and Zimbabwe. The Pan-African colors are borrowed from the flag of Ethiopia, one of the oldest independent African countries.[98][99] Rwanda, notably, removed red from its flag after the Rwandan genocide because of red's association with blood.[100]

The flags of Japan and Bangladesh both have a red circle in the middle of different colored backgrounds. The flag of the Philippines has a red trapezoid on the bottom signifying blood, courage, and valor (also, if the flag is inverted so that the red trapezoid is on top and the blue at the bottom, it indicates a state of war). The flag of Singapore has a red rectangle on the top. The field of the flag of Portugal is green and red. The Ottoman Empire adopted several different red flags during the six centuries of its rule, with the successor Republic of Turkey continuing the 1844 Ottoman flag.

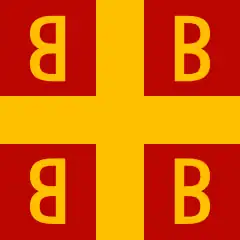

The flag of the Byzantine Empire from 1260 to its fall in 1453

The flag of the Byzantine Empire from 1260 to its fall in 1453 The St George's cross was the banner of the First Crusade, then, beginning in the 13th century, the flag of England. It is the red color (along with that of the Cross of Saint Patrick) in the flag of the United Kingdom, and, by adoption, of the red in the flag of the United States.

The St George's cross was the banner of the First Crusade, then, beginning in the 13th century, the flag of England. It is the red color (along with that of the Cross of Saint Patrick) in the flag of the United Kingdom, and, by adoption, of the red in the flag of the United States..svg.png.webp) The red stripes in the flag of the United States were adapted from the flag of the British East India Company. This is the Grand Union Flag, the first U.S. flag established by the Continental Congress.

The red stripes in the flag of the United States were adapted from the flag of the British East India Company. This is the Grand Union Flag, the first U.S. flag established by the Continental Congress. The Flag of Georgia also features the Saint George's Cross. It dates back to the banner of Medieval Georgia in the 5th century.

The Flag of Georgia also features the Saint George's Cross. It dates back to the banner of Medieval Georgia in the 5th century. The maple leaf flag of Canada, adopted in 1965. The red color comes from the Saint George's Cross of England.

The maple leaf flag of Canada, adopted in 1965. The red color comes from the Saint George's Cross of England.

In politics

In 18th-century Europe, red was usually associated with the monarchy and with those in power. The Pope wore red, as did the Swiss Guards of the Kings of France, the soldiers of the British Army and the Danish Army.

In the Roman Empire, freed slaves were given a red Phrygian cap as an emblem of their liberation. Because of this symbolism, the red "Liberty cap" became a symbol of the American patriots fighting for independence from England. During the French Revolution, the Jacobins also adapted the red Phrygian cap, and forced the deposed King Louis XVI to wear one after his arrest.[101]

Socialism and communism

In the 19th century, with the Industrial Revolution and the rise of worker's movements, red became the color of socialism (especially the Marxist variant), and, with the Paris Commune of 1871, of revolution.[63]

In the 20th century, red was the color first of the Russian Bolsheviks and then, after the success of the Russian Revolution of 1917, of communist parties around the world. However, after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia went back to the pre-revolutionary blue, white and red flag.

Red also became the color of many social democratic parties in Europe, including the Labour Party in Britain (founded 1900); the Social Democratic Party of Germany (whose roots went back to 1863) and the French Socialist Party, which dated back under different names, to 1879. The Socialist Party of America (1901–72) and the Communist Party USA (1919) both also chose red as their color.

Members of the Christian-Social People's Party in Liechtenstein (founded 1918) advocated an expansion of democracy and progressive social policies, and were often referred to disparagingly as "Reds" for their social liberal leanings and party colors.[102]

The Chinese Communist Party, founded in 1920, adopted the red flag and hammer and sickle emblem of the Soviet Union, which became the national symbols when the Party took power in China in 1949. Under Party leader Mao Zedong, the Party anthem became "The East Is Red",[103] and Mao Zedong himself was sometimes referred to as a "red sun".[104] During the Cultural Revolution in China, Party ideology was enforced by the Red Guards, and the sayings of Mao Zedong were published as a little red book in hundreds of millions of copies. Today the Chinese Communist Party claims to be the largest political party in the world, with eighty million members.[105]

Beginning in the 1960s and the 1970s, paramilitary extremist groups such as the Red Army Faction in Germany, the Japanese Red Army and the Shining Path Maoist movement in Peru used red as their color. But in the 1980s, some European socialist and social democratic parties, such as the Labour Party in Britain and the Socialist Party in France, moved away from the symbolism of the far left, keeping the red color but changing their symbol to a less-threatening red rose.

Red is used around the world by political parties of the left or center-left. In the United States, it is the color of the Communist Party USA, of the Social Democrats, USA, and in Puerto Rico, of the Popular Democratic Party.

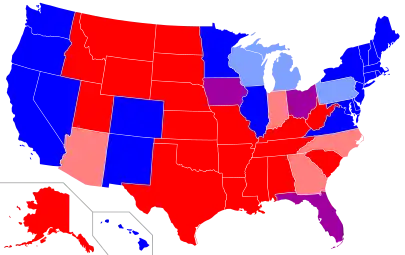

United States

In the United States, political commentators often refer to the "red states", which voted for Republican candidates in the last four presidential elections, and "blue states", which voted for Democrats. This convention is relatively recent: before the 2000 presidential election, media outlets assigned red and blue to both parties, sometimes alternating the allocation for each election. Fixed usage was established during the 39-day recount following the 2000 election, when the media began to discuss the contest in terms of "red states" versus "blue states".[106] States which voted for different parties in two of the last four presidential elections are called "Swing States", and are usually coloured purple, a mix of red and blue.[107]

Social and special interest groups

Such names as Red Club (a bar), Red Carpet (a discothèque) or Red Cottbus and Club Red (event locations) suggest liveliness and excitement. The Red Hat Society is a social group founded in 1998 for women 50 and over. Use of the color red to call attention to an emergency situation is evident in the names of such organizations as the Red Cross (humanitarian aid), Red Hot Organization (AIDS support), and the Red List of Threatened Species (of IUCN). In reference to humans, term "red" is often used in the West to describe the indigenous peoples of the Americas.[108]

Idioms

Many idiomatic expressions exploit the various connotations of red:

- Expressing emotion

- "to see red" (to be angry or aggressive)[109][110]

- "to have red ears / a red face" (to be embarrassed)[111]

- "to paint the town red" (to have an enjoyable evening, usually with a generous amount of eating, drinking, dancing)[112]

- Giving warning

- "to raise a red flag" (to signal that something is problematic)[113]

- "like a red rag to a bull" (to cause someone to be enraged)[114][115]

- "to be in the red" (to be losing money, from the accounting convention of writing deficits and losses in red ink)[116][117]

- Calling attention

- "a red letter day" (a special or important event, from the medieval custom of printing the dates of saints' days and holy days in red ink.)[118][119]

- "to roll out the red carpet" (to formally welcome an important guest)[120][121]

- "to give red-carpet treatment" (to treat someone as important or special)[121]

- "to catch someone red-handed" (to catch or discover someone doing something bad or wrong)[122]

- Other idioms

- "to tie up in red tape". In England red tape was used by lawyers and government officials to identify important documents. It became a term for excessive bureaucratic regulation. It was popularized in the 19th century by the writer Thomas Carlyle, who complained about "red-tapism".[123]

- "red herring". A false clue that leads investigators off the track. Refers to the practice of using a fragrant smoked fish to distract hunting or tracking dogs from the track they are meant to follow.[124][125]

- "red ink" (to show a business loss)[126]

References

Notes and citations

- Georgia State University Department of Physics and Astronomy. "Spectral Colors". HyperPhysics site. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- Maerz, A; Paul, M. R. (1930). A dictionary of color. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. OCLC 1150631.

- Chunling, Y. (2008). Chinese red. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 9787119045313. OCLC 319395390.

- Heller, Eva (1948). Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques. Paris: Pyramid. ISBN 9782350171562. OCLC 470802996.

- Ahearn, Laura M (2001). Invitation to love: Literacy, Love Letters, & Social Change in Nepal. Michigan: University of Michigan. p. 95.

- Selwyn, Tom (December 1979). "Images of Reproduction: An Analysis of a Hindu Marriage Ceremony". Man. 14 (4): 684–698. doi:10.2307/2802154. JSTOR 2802154.

- "What Wavelength Goes With a Color?". Atmospheric Science Data Center. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- Kalat, J. W. (2005). Introduction to psychology (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth. pp. 105. ISBN 978-0534624606. OCLC 56799330.

- Ali, Mohamed Ather; Klyne, M.A. (1985). Vision in Vertebrates. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 174–75. ISBN 978-0-306-42065-8.

- O'Neil, Dennis (March 19, 2010). "Primate Color Vision". Primates. San Marcos, California: Palomar Community College. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- Hogan, Dan; Hogan, Michele (May 25, 2007). "Color Vision Drove Primates To Develop Red Skin And Hair, Study Finds". Science News. Rockville, Maryland: ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- "Human Vision and Color Perception". Olympus Microscopy Resource Center. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved Nov 23, 2018.

- "Be a Stargazer". Sensitize Your Eyes. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- Broecke, Lara, ed. (2015). Cennino Cennini's Il libro dell'arte: a new English translation and commentary with Italian transcription. London: Archetype. p. 115. ISBN 9781909492288. OCLC 910400601. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- Briggs, David. "The Dimensions of Colour: Part 4. Additive Mixing". huevaluechroma.com. Archived from the original on November 13, 2018. Retrieved Nov 23, 2018.

- K. Saha (2008). The Earth's Atmosphere – Its Physics and Dynamics. Springer. p. 107. ISBN 978-3-540-78426-5.

- Guenther, B., ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of Modern Optics. Vol. 1. Elsevier. p. 186. ISBN 9780123693952.

- White, A. D.; Rigden, J. D. (1962). "Continuous Gas Maser Operation in the Visible". Proc. IRE. 50: 1697. US Patent 3242439.

- "Laserglow – Blue, Red, Yellow, Green Lasers". Laserglow.com. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved Sep 20, 2011.

- "Laserglow – Lab/OEM Lasers". Laserglow.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-15. Retrieved 2011-09-20.

- "DVD". usbyte.com. eMag Solutions LLC. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved Nov 23, 2018.

- Adams, Melanie; Raynor, Natasha (Sep 19, 1994 – Mar 12, 2009). "Mars, The Red Planet". MidLink Magazine. North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on July 12, 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- Cardall, Christian; Daunt, Steven (2003). "The Great Red Spot". The Solar System. University of Tennessee. Archived from the original on March 31, 2010. Retrieved Apr 12, 2010.

- Croswell, Ken. "The Brightest Red Dwarf". kencroswell.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved Nov 23, 2018.

- "From Shampoo to Cereal: Seeing to the Safety of Color Additives". Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- "Food Color Facts". January 1993. Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved 2006-08-18.

- "E129 – Allura Red AC". proe.info.

- "European Parliament and Council Directive 94/36/EC on colours for use in foodstuffs". European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Jun 30, 1994. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2018 – via EUR-Lex. Precise volume, tome, and page numbers for all languages are available on the cited website.

- Young, Saundra (Jun 30, 2010). "Group urges ban of 3 common dyes". CNN. Archived from the original on July 3, 2010. Retrieved Jul 1, 2010.

- Archetti, Marco; Döring, T. F.; Hagen, S. B.; et al. (2011). "Unravelling the evolution of autumn colours: an interdisciplinary approach". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 24 (3): 166–73. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.006. PMID 19178979.

- Davies, Kevin M., ed. (2004). Plant pigments and their manipulation. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 6. ISBN 978-1405117371. OCLC 56963804.

- "Why is blood red?". University of California, Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Nabili, Siamak. "Hemoglobin". Procedures and Tests. MedicineNet. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010. Retrieved Apr 12, 2010.

- Fleming, H. P.; Blumer, T. N.; Craig, H. B. (1960-11-01). "Quantitative Estimations of Myoglobin and Hemoglobin in Beef Muscle Extracts". Journal of Animal Science. 19 (4): 1164–1171. doi:10.2527/jas1960.1941164x. ISSN 0021-8812 – via WorldCat.

- Speer, Brian. "Photosynthetic Pigments". UCMP Glossary. University of California: University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- Garreau, Joel (Mar 18, 2002). "Red Alert!". The Garreau Group. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved Nov 23, 2018.

- "Hair Color". thetech.org. The Tech Museum of Innovation. 26 August 2004. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

When someone has both of their MC1R genes mutated, this conversion doesn't happen anymore and you get a buildup of pheomelanin, which results in red hair

- "redhead, n. and adj". OED Online. Oxford University Press. June 2011. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- Little, A. C.; Hill, R. A. (2007). "Attribution to red suggests special role in dominance signalling". Journal of Evolutionary Psychology. 5 (1): 161–168. doi:10.1556/JEP.2007.1008.

- Setchell, J.; Smith, T.; Wickings, E.; Knapp, L. (2008). "Social correlates of testosterone and ornamentation in male mandrills" (PDF). Hormones and Behavior. 54 (3): 365–72. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.05.004. PMID 18582885. S2CID 28843140. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-22. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- Cuthill, I. C.; Hunt, S.; Cleary, C.; Clark, C. (1997). "Colour bands, dominance, and body mass regulation in male zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 264 (1384): 1093–99. Bibcode:1997RSPSB.264.1093C. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0151. PMC 1688540.

- Hill, R. A.; Barton, R. A. (2005). "Psychology: Red enhances human performance in contests". Nature. 435 (7040): 293. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..293H. doi:10.1038/435293a. PMID 15902246. S2CID 4394988.

- Attrill, M.; Gresty, K.; Hill, R.; Barton, R. (2008). "Red shirt colour is associated with long-term team success in English football". Journal of Sports Sciences. 26 (6): 577–82. doi:10.1080/02640410701736244. PMID 18344128. S2CID 24581981.

- Ilie, A.; Ioan, S.; Zagrean, L.; Moldovan, M. (2008). "Better to Be Red than Blue in Virtual Competition". CyberPsychology & Behavior. 11 (3): 375–77. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.0122. PMID 18537513.

- Hackney, A. C. (2005). "Testosterone and human performance: influence of the color red". European Journal of Applied Physiology. 96 (3): 330–33. doi:10.1007/s00421-005-0059-7. PMID 16283371. S2CID 22517777.

- Hagemann, N.; Strauss, B.; Leissing, J. (2008). "When the Referee Sees Red …". Psychological Science. 19 (8): 769–71. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02155.x. PMID 18816283. S2CID 10618757.

- Elliot, A. J.; Maier, M. A. (2007). "Color and Psychological Functioning". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 16 (5): 250–54. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00514.x. S2CID 4678074.

- Elliot, A. J.; Maier, M. A.; Binser, M. J.; Friedman, R.; Pekrun, R. (2008). "The Effect of Red on Avoidance Behavior in Achievement Contexts". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 35 (3): 365–75. doi:10.1177/0146167208328330. PMID 19223458. S2CID 14453487.

- Marean, C. W.; Bar-Matthews, M; Bernatchez, J.; et al. (2007). "Early Human use of marine resources and pigment in South Africa during the Middle Pleistocene" (PDF). Nature. 449 (7164): 905–08. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..905M. doi:10.1038/nature06204. PMID 17943129. S2CID 4387442.

- Pastoureau, Michel; Simonnet, Dominique (2014). Le petit livre des couleurs. Paris: Seuil. p. 32. ISBN 9782757841532. OCLC 881055677.

- "Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain". unesco. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- Barber, E. J. W. (1991). Prehistoric Textiles. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691035970. OCLC 19922311.

- Greenfield, Amy Butler (2005). A perfect red. Paris: Autrement. ISBN 9782746710948. OCLC 470600856.

- "Pigments through the Ages – Intro to the reds". Webexhibits.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-04. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- Hamilton, R. (2007). Ancient Egypt: The Kingdom of the Pharaohs. Bath: Paragon Inc. pp. 62. ISBN 9781405486439. OCLC 144618068.

- Manniche, Lise (1999). Sacred luxuries. New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 127–43. ISBN 978-0801437205. OCLC 41319991. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- Feisner, Edith A. (2006). Colour (2nd ed.). London: Laurence King. p. 127. ISBN 978-1856694414. OCLC 62259546.

- Ramsay, William (1875). "Triumphus". Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- Hayes, A. W. (2008). Principles and Methods of Toxicology (5th ed.). New York: Informa Healthcare. ISBN 978-0-8493-3778-9.

- "Liturgical Colors". Catholic Online. Retrieved 2019-10-08.

- Herald, Catholic. "What do liturgical colors mean?- The Arlington Catholic Herald". catholicherald.com. Retrieved 2019-10-08.

- Pastoureau, Michel, "Rouge - Histoire d'une couleur" (2019), p. 166

- Traugott, Mark (2010). The Insurgent Barricade. University of California Press. pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-0-520-94773-3.

- Bowd, Stephen D. (2019-01-22). Renaissance Mass Murder: Civilians and Soldiers During the Italian Wars. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198832614. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- Naval War College Review. Naval War College. 1993. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- Rogoziński, Jan (2001-04-01). Honor Among Thieves: Captain Kidd, Henry Every, and the Story of Pirate Island. Conway. ISBN 9780851777924. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- Cordingly, p. 117. Cordingly cites only one source for pages 116–119 of his text: Calendar of State Papers, Colonial, America and West Indies, volumes 1719–20, no. 34.

- Conlin, Michael V.; Jolliffe, Lee (December 2016). Automobile Heritage and Tourism. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781315436203. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- "BBC SPORT | Motorsport | Formula One | Flags guide". news.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2019-11-02. Retrieved 2019-10-08.

- "Laws of The Game" (PDF). fifa.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. pp. 39, 72, 82–83. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved Mar 11, 2018.

- Robertson, S. A., ed. (1996). Contemporary ergonomics 1996. London: Taylor & Francis. pp. 148–50. ISBN 978-0748405497. OCLC 34731604.

- Karwowski, Waldemar (2006). International encyclopedia of ergonomics and human factors (2nd ed.). Boca Raton: CRC. p. 1518. ISBN 978-0415304306. OCLC 251383265.

- "Red ink banned from primary books". BBC News World Edition. Jan 23, 2003. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved Aug 15, 2013.

- "Red color in culture – HiSoUR – Hi So You Are". Retrieved 2023-05-19.

- says, fred Wright (2017-08-07). "Why Do Lifeguards Wear Red?". Kiefer Swim Shop Blog. Archived from the original on 2020-11-01. Retrieved 2020-09-09.

- "Lifesaver and Lifeguard Uniforms" (PDF). International Life Saving Federation.

- Oehler, Gustav Friedrich (2015). Day, George E. (ed.). Theology of the Old Testament. Arkose Press. p. 320. ISBN 9781345212341.

- St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. pp. 136–137. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- "Isaiah 1:18 - King James Version". Bible Gateway. Archived from the original on November 27, 2018. Retrieved Nov 26, 2018.

Come now, and let us reason together, saith the Lord: though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool.

- "Revelation 17 - King James Version". Bible Gateway. Archived from the original on November 26, 2018. Retrieved Nov 26, 2018.

- Steffler, Alva W. (2002). Symbols of the Christian faith. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. p. 132. ISBN 978-0802846761. OCLC 48557619.

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel (2004). Brantley, Margaret (ed.). The scarlet letter. New York: Pocket. pp. 136. ISBN 978-0743487566. OCLC 55483830.

- "Red Light District Amsterdam | Amsterdam.info". www.amsterdam.info. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- Finlay, Leslie (2018-03-27). "A Guide to Bangkok's Red Light Districts". Culture Trip. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- "red-handed". Cambridge Dictionary. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- The World Book Encyclopedia. Vol. 19. Chicago: Scott Fetzer Company. 2003. p. 36. ISBN 0-7166-0103-6. OCLC 50204221.

- Ni, Xueting C. (2023). Chinese Myths: From Cosmology and Folklore to Gods and Immortals. London: Amber Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-83886-263-3.

- d'Ami, Rinaldo (1968). World uniforms in colour: Vol. 2: Nations of America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. London: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-0850590319. OCLC 14994.

- Korkolis, M. (July 1986). "APP-6 Military Symbols For Land Based Symbols" (PDF). alternatewars.com. pp. 1–4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-06-19. Retrieved 2018-11-14.

- Gibbon, Edward (1960). Low, M. D. (ed.). The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. New York: Harcourt. p. 554. ISBN 978-0151355372. OCLC 402038.

- Dart, Tom (Mar 12, 2008). "Teams with red shirts have a head start". Times Online. London: News International Group. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved Apr 13, 2010.

- Cuordileone, Kyle A. (2005). Manhood and American Political Culture in the Cold War. New York: Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-0415925990. OCLC 56535047.

- Pastoureau, "Rouge - Histoire d'un couleur" (2019), p. 177

- Brabazon, Tara (2000). Tracking the jack. Sydney: UNSW Press. ISBN 978-0868406992. OCLC 50382088.

- "The United States Flag – Public and Intergovernmental Affairs". United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on December 31, 2006. Retrieved Dec 7, 2006.

- "The Life of the Führer". German Propaganda Archive. Calvin.edu. 1938. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved Sep 8, 2012.

- Hitler, Adolf (1926). "Chapter VII". Mein Kampf. Vol. 2.

- "Colors as Symbols in Flags". EnchantedLearning.com. Archived from the original on 2011-12-28. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- Murrell, Nathaniel S.; et al. (1998). Chanting Down Babylon. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 135. ISBN 978-1566395830. OCLC 37115199.

- "Rwandan: Adoption of the new flag". Crwflags.com. Dec 31, 2005. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved Dec 17, 2011.

- Pastoureau, Michel, "Rouge - Histoire d'une couleur" (2019), p. 166

- "Christlich-soziale Volkspartei". e-archiv.li (in German). Liechtenstein National Archives. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- "The East Is Red". TIME. 1970-05-04. Archived from the original on 2009-02-11. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- "The Reddest Red Sun". Morning Sun. Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- "China's Communist Party members exceed 80 million". News.xinhuanet.com. 2011-06-24. Archived from the original on 2011-09-29. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- Farhi, Paul (Nov 2, 2004). "Elephants Are Red, Donkeys Are Blue". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved Apr 19, 2011.

- "What Are Swing States and How Did They Become a Key Factor in US Elections?". HISTORY. 7 October 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Larsen, Nick (1995). The Canadian Criminal Justice System. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press. p. 440. ISBN 978-1551300467. OCLC 30666261.

- "see red". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- Fetterman, Adam K.; Robinson, Michael D.; Gordon, Robert D.; Elliot, Andrew J. (November 4, 2010). "Anger as Seeing Red: Perceptual Sources of Evidence". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2 (3): 311–316. doi:10.1177/1948550610390051. ISSN 1948-5506. PMC 3399410. PMID 22822418.

- Services, Department of Health & Human. "Blushing and flushing". www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- "paint the town red". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- "Definition of RED-FLAG". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- Martin, Gary. "'A red rag to a bull' - the meaning and origin of this phrase". Phrasefinder. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- "Definition of A RED RAG TO A BULL". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- Martin, Gary. "'In the red' - the meaning and origin of this phrase". Phrasefinder. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- "Definition of IN THE RED". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- "Definition of RED-LETTER DAY". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- "British Library". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- "Definition of roll out the red carpet". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- "Red carpet Idiom Definition". 2018-03-05. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- "catch someone red-handed". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- Hendrickson, Robert (2008). The Facts on File encyclopedia of word and phrase origins (PDF) (4th ed.). New York: Facts On File, Inc. ISBN 9780816069668. OCLC 166383622. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- Red-Herring (2019-05-15). "Red Herring". www.txst.edu. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- "Home : Oxford English Dictionary". www.oed.com. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- "Definition of RED INK". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

Bibliography

- Broecke, Lara (2015). Cennino Cennini's Il Libro dell'Arte: a New English Translation and Commentary with italian Transcription. Archetype. ISBN 978-1-909492-28-8.

- Barber, E. j. w. (1991). Prehistoric Textiles. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00224-8.

- Greenfield, Amy Butler (2005). A Perfect Red. Editions Autrement (French translation). ISBN 978-2-7467-1094-8.

- Ball, Philip (2001). Bright Earth, Art and the Invention of Colour. Hazan (French translation). ISBN 978-2-7541-0503-3.

- Heller, Eva (2009). Psychologie de la couleur – Effets et symboliques. Pyramyd (French translation). ISBN 978-2-35017-156-2.

- Chunling, Yan (2008). China Red. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 978-7-119-04531-3.

- Pastoureau, Michel (2019). Rouge - Histoire d'une couleur. Éditions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-7578-7820-0.