Underwater acoustics

Underwater acoustics (also known as hydroacoustics) is the study of the propagation of sound in water and the interaction of the mechanical waves that constitute sound with the water, its contents and its boundaries. The water may be in the ocean, a lake, a river or a tank. Typical frequencies associated with underwater acoustics are between 10 Hz and 1 MHz. The propagation of sound in the ocean at frequencies lower than 10 Hz is usually not possible without penetrating deep into the seabed, whereas frequencies above 1 MHz are rarely used because they are absorbed very quickly.

Hydroacoustics, using sonar technology, is most commonly used for monitoring of underwater physical and biological characteristics. Hydroacoustics can be used to detect the depth of a water body (bathymetry), as well as the presence or absence, abundance, distribution, size, and behavior of underwater plants[1] and animals. Hydroacoustic sensing involves "passive acoustics" (listening for sounds) or active acoustics making a sound and listening for the echo, hence the common name for the device, echo sounder or echosounder.

There are a number of different causes of noise from shipping. These can be subdivided into those caused by the propeller, those caused by machinery, and those caused by the movement of the hull through the water. The relative importance of these three different categories will depend, amongst other things, on the ship type[lower-alpha 1]

One of the main causes of hydro acoustic noise from fully submerged lifting surfaces is the unsteady separated turbulent flow near the surface's trailing edge that produces pressure fluctuations on the surface and unsteady oscillatory flow in the near wake. The relative motion between the surface and the ocean creates a turbulent boundary layer (TBL) that surrounds the surface. The noise is generated by the fluctuating velocity and pressure fields within this TBL.

The field of underwater acoustics is closely related to a number of other fields of acoustic study, including sonar, transduction, signal processing, acoustical oceanography, bioacoustics, and physical acoustics.

History

Underwater sound has probably been used by marine animals for millions of years. The science of underwater acoustics began in 1490, when Leonardo da Vinci wrote the following,[2]

- "If you cause your ship to stop and place the head of a long tube in the water and place the outer extremity to your ear, you will hear ships at a great distance from you."

In 1687 Isaac Newton wrote his Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy which included the first mathematical treatment of sound. The next major step in the development of underwater acoustics was made by Daniel Colladon, a Swiss physicist, and Charles Sturm, a French mathematician. In 1826, on Lake Geneva, they measured the elapsed time between a flash of light and the sound of a submerged ship's bell heard using an underwater listening horn.[3] They measured a sound speed of 1435 metres per second over a 17 kilometre (km) distance, providing the first quantitative measurement of sound speed in water.[4] The result they obtained was within about 2% of currently accepted values. In 1877 Lord Rayleigh wrote the Theory of Sound and established modern acoustic theory.

The sinking of Titanic in 1912 and the start of World War I provided the impetus for the next wave of progress in underwater acoustics. Systems for detecting icebergs and U-boats were developed. Between 1912 and 1914, a number of echolocation patents were granted in Europe and the U.S., culminating in Reginald A. Fessenden's echo-ranger in 1914. Pioneering work was carried out during this time in France by Paul Langevin and in Britain by A B Wood and associates.[5] The development of both active ASDIC and passive sonar (SOund Navigation And Ranging) proceeded apace during the war, driven by the first large scale deployments of submarines. Other advances in underwater acoustics included the development of acoustic mines.

In 1919, the first scientific paper on underwater acoustics was published,[6] theoretically describing the refraction of sound waves produced by temperature and salinity gradients in the ocean. The range predictions of the paper were experimentally validated by propagation loss measurements.

The next two decades saw the development of several applications of underwater acoustics. The fathometer, or depth sounder, was developed commercially during the 1920s. Originally natural materials were used for the transducers, but by the 1930s sonar systems incorporating piezoelectric transducers made from synthetic materials were being used for passive listening systems and for active echo-ranging systems. These systems were used to good effect during World War II by both submarines and anti-submarine vessels. Many advances in underwater acoustics were made which were summarised later in the series Physics of Sound in the Sea, published in 1946.

After World War II, the development of sonar systems was driven largely by the Cold War, resulting in advances in the theoretical and practical understanding of underwater acoustics, aided by computer-based techniques.

Theory

Sound waves in water, bottom of sea

A sound wave propagating underwater consists of alternating compressions and rarefactions of the water. These compressions and rarefactions are detected by a receiver, such as the human ear or a hydrophone, as changes in pressure. These waves may be man-made or naturally generated.

Speed of sound, density and impedance

The speed of sound (i.e., the longitudinal motion of wavefronts) is related to frequency and wavelength of a wave by .

This is different from the particle velocity , which refers to the motion of molecules in the medium due to the sound, and relates to the plane wave pressure to the fluid density and sound speed by .

The product of and from the above formula is known as the characteristic acoustic impedance. The acoustic power (energy per second) crossing unit area is known as the intensity of the wave and for a plane wave the average intensity is given by , where is the root mean square acoustic pressure.

Sometimes the term "sound velocity" is used but this is incorrect as the quantity is a scalar.

The large impedance contrast between air and water (the ratio is about 3600) and the scale of surface roughness means that the sea surface behaves as an almost perfect reflector of sound at frequencies below 1 kHz. Sound speed in water exceeds that in air by a factor of 4.4 and the density ratio is about 820.

Absorption of sound

Absorption of low frequency sound is weak.[7] (see Technical Guides – Calculation of absorption of sound in seawater for an on-line calculator). The main cause of sound attenuation in fresh water, and at high frequency in sea water (above 100 kHz) is viscosity. Important additional contributions at lower frequency in seawater are associated with the ionic relaxation of boric acid (up to c. 10 kHz)[7] and magnesium sulfate (c. 10 kHz-100 kHz).[8]

Sound may be absorbed by losses at the fluid boundaries. Near the surface of the sea losses can occur in a bubble layer or in ice, while at the bottom sound can penetrate into the sediment and be absorbed.

Boundary interactions

Both the water surface and bottom are reflecting and scattering boundaries.

Surface

For many purposes the sea-air surface can be thought of as a perfect reflector. The impedance contrast is so great that little energy is able to cross this boundary. Acoustic pressure waves reflected from the sea surface experience a reversal in phase, often stated as either a "pi phase change" or a "180 deg phase change". This is represented mathematically by assigning a reflection coefficient of minus 1 instead of plus one to the sea surface.[9]

At high frequency (above about 1 kHz) or when the sea is rough, some of the incident sound is scattered, and this is taken into account by assigning a reflection coefficient whose magnitude is less than one. For example, close to normal incidence, the reflection coefficient becomes , where h is the rms wave height.[10]

A further complication is the presence of wind-generated bubbles or fish close to the sea surface.[11] The bubbles can also form plumes that absorb some of the incident and scattered sound, and scatter some of the sound themselves.[12]

Seabed

The acoustic impedance mismatch between water and the bottom is generally much less than at the surface and is more complex. It depends on the bottom material types and depth of the layers. Theories have been developed for predicting the sound propagation in the bottom in this case, for example by Biot [13] and by Buckingham.[14]

At target

The reflection of sound at a target whose dimensions are large compared with the acoustic wavelength depends on its size and shape as well as the impedance of the target relative to that of water. Formulae have been developed for the target strength of various simple shapes as a function of angle of sound incidence. More complex shapes may be approximated by combining these simple ones.[2]

Propagation of sound

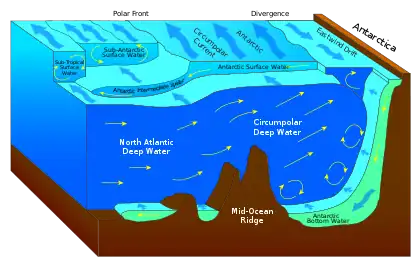

Underwater acoustic propagation depends on many factors. The direction of sound propagation is determined by the sound speed gradients in the water. These speed gradients transform the sound wave through refraction, reflection, and dispersion. In the sea the vertical gradients are generally much larger than the horizontal ones. Combining this with a tendency towards increasing sound speed at increasing depth, due to the increasing pressure in the deep sea, causes a reversal of the sound speed gradient in the thermocline, creating an efficient waveguide at the depth, corresponding to the minimum sound speed. The sound speed profile may cause regions of low sound intensity called "Shadow Zones", and regions of high intensity called "Caustics". These may be found by ray tracing methods.

At the equator and temperate latitudes in the ocean, the surface temperature is high enough to reverse the pressure effect, such that a sound speed minimum occurs at depth of a few hundred meters. The presence of this minimum creates a special channel known as deep sound channel, or SOFAR (sound fixing and ranging) channel, permitting guided propagation of underwater sound for thousands of kilometers without interaction with the sea surface or the seabed. Another phenomenon in the deep sea is the formation of sound focusing areas, known as convergence zones. In this case sound is refracted downward from a near-surface source and then back up again. The horizontal distance from the source at which this occurs depends on the positive and negative sound speed gradients. A surface duct can also occur in both deep and moderately shallow water when there is upward refraction, for example due to cold surface temperatures. Propagation is by repeated sound bounces off the surface.

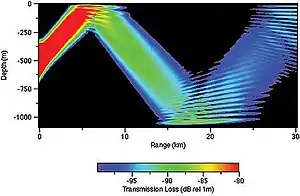

In general, as sound propagates underwater there is a reduction in the sound intensity over increasing ranges, though in some circumstances a gain can be obtained due to focusing. Propagation loss (sometimes referred to as transmission loss) is a quantitative measure of the reduction in sound intensity between two points, normally the sound source and a distant receiver. If is the far field intensity of the source referred to a point 1 m from its acoustic center and is the intensity at the receiver, then the propagation loss is given by[2] . In this equation is not the true acoustic intensity at the receiver, which is a vector quantity, but a scalar equal to the equivalent plane wave intensity (EPWI) of the sound field. The EPWI is defined as the magnitude of the intensity of a plane wave of the same RMS pressure as the true acoustic field. At short range the propagation loss is dominated by spreading while at long range it is dominated by absorption and/or scattering losses.

An alternative definition is possible in terms of pressure instead of intensity,[15] giving , where is the RMS acoustic pressure in the far-field of the projector, scaled to a standard distance of 1 m, and is the RMS pressure at the receiver position.

These two definitions are not exactly equivalent because the characteristic impedance at the receiver may be different from that at the source. Because of this, the use of the intensity definition leads to a different sonar equation to the definition based on a pressure ratio.[16] If the source and receiver are both in water, the difference is small.

Propagation modelling

The propagation of sound through water is described by the wave equation, with appropriate boundary conditions. A number of models have been developed to simplify propagation calculations. These models include ray theory, normal mode solutions, and parabolic equation simplifications of the wave equation.[17] Each set of solutions is generally valid and computationally efficient in a limited frequency and range regime, and may involve other limits as well. Ray theory is more appropriate at short range and high frequency, while the other solutions function better at long range and low frequency.[18][19][20] Various empirical and analytical formulae have also been derived from measurements that are useful approximations.[21]

Reverberation

Transient sounds result in a decaying background that can be of much larger duration than the original transient signal. The cause of this background, known as reverberation, is partly due to scattering from rough boundaries and partly due to scattering from fish and other biota. For an acoustic signal to be detected easily, it must exceed the reverberation level as well as the background noise level.

Doppler shift

If an underwater object is moving relative to an underwater receiver, the frequency of the received sound is different from that of the sound radiated (or reflected) by the object. This change in frequency is known as a Doppler shift. The shift can be easily observed in active sonar systems, particularly narrow-band ones, because the transmitter frequency is known, and the relative motion between sonar and object can be calculated. Sometimes the frequency of the radiated noise (a tonal) may also be known, in which case the same calculation can be done for passive sonar. For active systems the change in frequency is 0.69 Hz per knot per kHz and half this for passive systems as propagation is only one way. The shift corresponds to an increase in frequency for an approaching target.

Intensity fluctuations

Though acoustic propagation modelling generally predicts a constant received sound level, in practice there are both temporal and spatial fluctuations. These may be due to both small and large scale environmental phenomena. These can include sound speed profile fine structure and frontal zones as well as internal waves. Because in general there are multiple propagation paths between a source and receiver, small phase changes in the interference pattern between these paths can lead to large fluctuations in sound intensity.

Non-linearity

In water, especially with air bubbles, the change in density due to a change in pressure is not exactly linearly proportional. As a consequence for a sinusoidal wave input additional harmonic and subharmonic frequencies are generated. When two sinusoidal waves are input, sum and difference frequencies are generated. The conversion process is greater at high source levels than small ones. Because of the non-linearity there is a dependence of sound speed on the pressure amplitude so that large changes travel faster than small ones. Thus a sinusoidal waveform gradually becomes a sawtooth one with a steep rise and a gradual tail. Use is made of this phenomenon in parametric sonar and theories have been developed to account for this, e.g. by Westerfield.

Measurements

Sound in water is measured using a hydrophone, which is the underwater equivalent of a microphone. A hydrophone measures pressure fluctuations, and these are usually converted to sound pressure level (SPL), which is a logarithmic measure of the mean square acoustic pressure.

Measurements are usually reported in one of two forms:

- RMS acoustic pressure in pascals (or sound pressure level (SPL) in dB re 1 μPa)

- spectral density (mean square pressure per unit bandwidth) in pascals squared per hertz (dB re 1 μPa2/Hz)

The scale for acoustic pressure in water differs from that used for sound in air. In air the reference pressure is 20 μPa rather than 1 μPa. For the same numerical value of SPL, the intensity of a plane wave (power per unit area, proportional to mean square sound pressure divided by acoustic impedance) in air is about 202×3600 = 1 440 000 times higher than in water. Similarly, the intensity is about the same if the SPL is 61.6 dB higher in the water.

The 2017 standard ISO 18405 defines terms and expressions used in the field of underwater acoustics, including the calculation of underwater sound pressure levels.

Sound speed

Approximate values for fresh water and seawater, respectively, at atmospheric pressure are 1450 and 1500 m/s for the sound speed, and 1000 and 1030 kg/m3 for the density.[22] The speed of sound in water increases with increasing pressure, temperature and salinity.[23][24] The maximum speed in pure water under atmospheric pressure is attained at about 74 °C; sound travels slower in hotter water after that point; the maximum increases with pressure.[25]

Absorption

Many measurements have been made of sound absorption in lakes and the ocean [7][8] (see Technical Guides – Calculation of absorption of sound in seawater for an on-line calculator).

Ambient noise

Measurement of acoustic signals are possible if their amplitude exceeds a minimum threshold, determined partly by the signal processing used and partly by the level of background noise. Ambient noise is that part of the received noise that is independent of the source, receiver and platform characteristics. Thus it excludes reverberation and towing noise for example.

The background noise present in the ocean, or ambient noise, has many different sources and varies with location and frequency.[26] At the lowest frequencies, from about 0.1 Hz to 10 Hz, ocean turbulence and microseisms are the primary contributors to the noise background.[27] Typical noise spectrum levels decrease with increasing frequency from about 140 dB re 1 μPa2/Hz at 1 Hz to about 30 dB re 1 μPa2/Hz at 100 kHz. Distant ship traffic is one of the dominant noise sources[28] in most areas for frequencies of around 100 Hz, while wind-induced surface noise is the main source between 1 kHz and 30 kHz. At very high frequencies, above 100 kHz, thermal noise of water molecules begins to dominate. The thermal noise spectral level at 100 kHz is 25 dB re 1 μPa2/Hz. The spectral density of thermal noise increases by 20 dB per decade (approximately 6 dB per octave).[29]

Transient sound sources also contribute to ambient noise. These can include intermittent geological activity, such as earthquakes and underwater volcanoes,[30] rainfall on the surface, and biological activity. Biological sources include cetaceans (especially blue, fin and sperm whales),[31][32] certain types of fish, and snapping shrimp.

Rain can produce high levels of ambient noise. However the numerical relationship between rain rate and ambient noise level is difficult to determine because measurement of rain rate is problematic at sea.

Reverberation

Many measurements have been made of sea surface, bottom and volume reverberation. Empirical models have sometimes been derived from these. A commonly used expression for the band 0.4 to 6.4 kHz is that by Chapman and Harris.[33] It is found that a sinusoidal waveform is spread in frequency due to the surface motion. For bottom reverberation a Lambert's Law is found often to apply approximately, for example see Mackenzie.[34] Volume reverberation is usually found to occur mainly in layers, which change depth with the time of day, e.g., see Marshall and Chapman.[35] The under-surface of ice can produce strong reverberation when it is rough, see for example Milne.[36]

Bottom loss

Bottom loss has been measured as a function of grazing angle for many frequencies in various locations, for example those by the US Marine Geophysical Survey.[37] The loss depends on the sound speed in the bottom (which is affected by gradients and layering) and by roughness. Graphs have been produced for the loss to be expected in particular circumstances. In shallow water bottom loss often has the dominant impact on long range propagation. At low frequencies sound can propagate through the sediment then back into the water.

Underwater hearing

Comparison with airborne sound levels

As with airborne sound, sound pressure level underwater is usually reported in units of decibels, but there are some important differences that make it difficult (and often inappropriate) to compare SPL in water with SPL in air. These differences include:[38]

- difference in reference pressure: 1 μPa (one micropascal, or one millionth of a pascal) instead of 20 μPa.[15]

- difference in interpretation: there are two schools of thought, one maintaining that pressures should be compared directly, and the other that one should first convert to the intensity of an equivalent plane wave.

- difference in hearing sensitivity: any comparison with (A-weighted) sound in air needs to take into account the differences in hearing sensitivity, either of a human diver or other animal.[39]

Hearing sensitivity

The lowest audible SPL for a human diver with normal hearing is about 67 dB re 1 μPa, with greatest sensitivity occurring at frequencies around 1 kHz.[40] This corresponds to a sound intensity 5.4 dB, or 3.5 times, higher than the threshold in air (see Measurements above).

Safety thresholds

High levels of underwater sound create a potential hazard to human divers.[41] Guidelines for exposure of human divers to underwater sound are reported by the SOLMAR project of the NATO Undersea Research Centre.[42] Human divers exposed to SPL above 154 dB re 1 μPa in the frequency range 0.6 to 2.5 kHz are reported to experience changes in their heart rate or breathing frequency. Diver aversion to low frequency sound is dependent upon sound pressure level and center frequency.[43]

Aquatic mammals

Dolphins and other toothed whales are known for their acute hearing sensitivity, especially in the frequency range 5 to 50 kHz.[39][44] Several species have hearing thresholds between 30 and 50 dB re 1 μPa in this frequency range. For example, the hearing threshold of the killer whale occurs at an RMS acoustic pressure of 0.02 mPa (and frequency 15 kHz), corresponding to an SPL threshold of 26 dB re 1 μPa.[45]

High levels of underwater sound create a potential hazard to marine and amphibious animals.[39] The effects of exposure to underwater noise are reviewed by Southall et al.[46]

Fish

The hearing sensitivity of fish is reviewed by Ladich and Fay.[47] The hearing threshold of the soldier fish, is 0.32 mPa (50 dB re 1 μPa) at 1.3 kHz, whereas the lobster has a hearing threshold of 1.3 Pa at 70 Hz (122 dB re 1 μPa).[45] The effects of exposure to underwater noise are reviewed by Popper et al.[48]

Aquatic birds

Several aquatic bird species have been observed to react to underwater sound in the 1-4 kHz range,[49] which follows the frequency range of best hearing sensitivities of birds in air. Seaducks and cormorants have been trained to respond to sounds of 1-4 kHz with lowest hearing threshold (highest sensitivity) of 71 dB re 1 μPa[50] (cormorants) and 105 dB re 1 μPa (seaducks).[51] Diving species have several morphological differences in the ear relative to terrestrial species, suggesting some adaptations of the ear in diving birds to aquatic conditions[52]

Applications of underwater acoustics

Sonar

Sonar is the name given to the acoustic equivalent of radar. Pulses of sound are used to probe the sea, and the echoes are then processed to extract information about the sea, its boundaries and submerged objects. An alternative use, known as passive sonar, attempts to do the same by listening to the sounds radiated by underwater objects.

Underwater communication

The need for underwater acoustic telemetry exists in applications such as data harvesting for environmental monitoring, communication with and between manned and unmanned underwater vehicles, transmission of diver speech, etc. A related application is underwater remote control, in which acoustic telemetry is used to remotely actuate a switch or trigger an event. A prominent example of underwater remote control are acoustic releases, devices that are used to return sea floor deployed instrument packages or other payloads to the surface per remote command at the end of a deployment. Acoustic communications form an active field of research [53][54] with significant challenges to overcome, especially in horizontal, shallow-water channels. Compared with radio telecommunications, the available bandwidth is reduced by several orders of magnitude. Moreover, the low speed of sound causes multipath propagation to stretch over time delay intervals of tens or hundreds of milliseconds, as well as significant Doppler shifts and spreading. Often acoustic communication systems are not limited by noise, but by reverberation and time variability beyond the capability of receiver algorithms. The fidelity of underwater communication links can be greatly improved by the use of hydrophone arrays, which allow processing techniques such as adaptive beamforming and diversity combining.

Underwater navigation and tracking

Underwater navigation and tracking is a common requirement for exploration and work by divers, ROV, autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV), manned submersibles and submarines alike. Unlike most radio signals which are quickly absorbed, sound propagates far underwater and at a rate that can be precisely measured or estimated.[55] It can thus be used to measure distances between a tracked target and one or multiple reference of baseline stations precisely, and triangulate the position of the target, sometimes with centimeter accuracy. Starting in the 1960s, this has given rise to underwater acoustic positioning systems which are now widely used.

Seismic exploration

Seismic exploration involves the use of low frequency sound (< 100 Hz) to probe deep into the seabed. Despite the relatively poor resolution due to their long wavelength, low frequency sounds are preferred because high frequencies are heavily attenuated when they travel through the seabed. Sound sources used include airguns, vibroseis and explosives.

Weather and climate observation

Acoustic sensors can be used to monitor the sound made by wind and precipitation. For example, an acoustic rain gauge is described by Nystuen.[56] Lightning strikes can also be detected.[57] Acoustic thermometry of ocean climate (ATOC) uses low frequency sound to measure the global ocean temperature.

Acoustical oceanography

Acoustical oceanography is the use of underwater sound to study the sea, its boundaries and its contents.

History

Interest in developing echo ranging systems began in earnest following the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912. By sending a sound wave ahead of a ship, the theory went, a return echo bouncing off the submerged portion of an iceberg should give early warning of collisions. By directing the same type of beam downwards, the depth to the bottom of the ocean could be calculated.[58]

The first practical deep-ocean echo sounder was invented by Harvey C. Hayes, a U.S. Navy physicist. For the first time, it was possible to create a quasi-continuous profile of the ocean floor along the course of a ship. The first such profile was made by Hayes on board the U.S.S. Stewart, a Navy destroyer that sailed from Newport to Gibraltar between June 22 and 29, 1922. During that week, 900 deep-ocean soundings were made.[59]

Using a refined echo sounder, the German survey ship Meteor made several passes across the South Atlantic from the equator to Antarctica between 1925 and 1927, taking soundings every 5 to 20 miles. Their work created the first detailed map of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It showed that the Ridge was a rugged mountain range, and not the smooth plateau that some scientists had envisioned. Since that time, both naval and research vessels have operated echo sounders almost continuously while at sea.[60]

Important contributions to acoustical oceanography have been made by:

- Leonid Brekhovskikh

- Walter Munk

- Herman Medwin

- John L. Spiesberger

- C.C. Leroy

- David E. Weston

- D. Van Holliday

- Charles Greenlaw

Equipment used

The earliest and most widespread use of sound and sonar technology to study the properties of the sea is the use of a rainbow echo sounder to measure water depth. Sounders were the devices used that mapped the many miles of the Santa Barbara Harbor ocean floor until 1993.

Fathometers measure the depth of the waters. It works by electronically sending sounds from ships, therefore also receiving the sound waves that bounces back from the bottom of the ocean. A paper chart moves through the fathometer and is calibrated to record the depth.

As technology advances, the development of high resolution sonars in the second half of the 20th century made it possible to not just detect underwater objects but to classify them and even image them. Electronic sensors are now attached to ROVs since nowadays, ships or robot submarines have Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs). There are cameras attached to these devices giving out accurate images. The oceanographers are able to get a clear and precise quality of pictures. The 'pictures' can also be sent from sonars by having sound reflected off ocean surroundings. Oftentimes sound waves reflect off animals, giving information which can be documented into deeper animal behaviour studies.[61][62][63]

Marine biology

Due to its excellent propagation properties, underwater sound is used as a tool to aid the study of marine life, from microplankton to the blue whale. Echo sounders are often used to provide data on marine life abundance, distribution, and behavior information. Echo sounders, also referred to as hydroacoustics is also used for fish location, quantity, size, and biomass.

Acoustic telemetry is also used for monitoring fish and marine wildlife. An acoustic transmitter is attached to the fish (sometimes internally) while an array of receivers listen to the information conveyed by the sound wave. This enables the researchers to track the movements of individuals in a small-medium scale.[64]

Pistol shrimp create sonoluminescent cavitation bubbles that reach up to 5,000 K (4,700 °C) [65]

Particle physics

A neutrino is a fundamental particle that interacts very weakly with other matter. For this reason, it requires detection apparatus on a very large scale, and the ocean is sometimes used for this purpose. In particular, it is thought that ultra-high energy neutrinos in seawater can be detected acoustically.[66]

Other applications

Other applications include:

- rain rate measurement

- wind speed measurement

- global thermometry

- monitoring of ocean-atmospheric gas exchange

- Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System

- Acoustic Doppler current profiler for water speed measurement

- Acoustic camera

- Liquid sound

- Passive acoustic monitoring

See also

- Bioacoustics – Study of sound relating to biology

- Cambridge Interferometer – a radio telescope interferometer built in the early 1950s to the west of Cambridge, UK

- Echo sounder – Measuring the depth of water by transmitting sound waves into water and timing the return

- Fisheries acoustics

- Hydroacoustics – Study of the propagation of sound in water

- Ocean exploration – Part of oceanography describing the exploration of ocean surfaces

- Ocean Tracking Network

- Refraction (sound) – Change of direction of propagation due to variation of velocity

- Sonar – Acoustic sensing method

- Underwater acoustic positioning system – System for tracking and navigation of underwater vehicles or divers using acoustic signals

- Underwater acoustic communication – Wireless technique of sending and receiving messages through water

- Underwater Audio, an electronics company

Notes

- reducing underwater noise pollution from large commercial vessels

References

- "Submersed Aquatic Vegetation Early Warning System (SAVEWS)". Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- Urick, Robert J. Principles of Underwater Sound, 3rd Edition. New York. McGraw-Hill, 1983.

- C. S. Clay & H. Medwin, Acoustical Oceanography (Wiley, New York, 1977)

- Annales de Chimie et de Physique 36 [2] 236 (1827)

- A. B. Wood, From the Board of Invention and Research to the Royal Naval Scientific Service, Journal of the Royal Naval Scientific Service Vol 20, No 4, pp 1–100 (185–284).

- H. Lichte (1919). "On the influence of horizontal temperature layers in sea water on the range of underwater sound signals". Phys. Z. 17 (385).

- R. E. Francois & G. R. Garrison, Sound absorption based on ocean measurements. Part II: Boric acid contribution and equation for total absorption, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 72, 1879–1890 (1982).

- R. E. Francois and G. R. Garrison, Sound absorption based on ocean measurements. Part I: Pure water and magnesium sulfate contributions, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 72, 896–907 (1982).

- Ainslie, M. A. (2010). Principles of Sonar Performance Modeling. Berlin: Springer. p36

- H. Medwin & C. S. Clay, Fundamentals of Acoustical Oceanography (Academic, Boston, 1998).

- D. E. Weston & P. A. Ching, Wind effects in shallow-water transmission, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 86, 1530–1545 (1989).

- G. V. Norton & J. C. Novarini, On the relative role of sea-surface roughness and bubble plumes in shallow-water propagation in the low-kilohertz region, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110, 2946–2955 (2001)

- N Chotiros, Biot Model of Sound Propagation in Water Saturated Sand. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 97, 199 (1995)

- M. J. Buckingham, Wave propagation, stress relaxation, and grain-to-grain shearing in saturated, unconsolidated marine sediments, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 108, 2796–2815 (2000).

- C. L. Morfey, Dictionary of Acoustics (Academic Press, San Diego, 2001).

- M. A. Ainslie, The sonar equation and the definitions of propagation loss, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 115, 131–134 (2004).

- F. B. Jensen, W. A. Kuperman, M. B. Porter & H. Schmidt, Computational Ocean Acoustics (AIP Press, NY, 1994).

- C. H. Harrison, Ocean propagation models, Applied Acoustics 27, 163–201 (1989).

- Muratov, R. Z.; Efimov, S. P. (1978). "Low frequency scattering of a plane wave by an acoustically soft ellipsoid". Radiophysics and Quantum Electronics. 21 (2): 153–160. Bibcode:1978R&QE...21..153M. doi:10.1007/BF01078707. S2CID 118762566.

- Morse, Philip M.; Ingard, K. Uno (1987). Theoretical Acoustics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 949. ISBN 9780691024011.

- L. M. Brekhovskikh & Yu. P. Lysanov, Fundamentals of Ocean Acoustics, 3rd edition (Springer-Verlag, NY, 2003).

- A. D. Pierce, Acoustics: An Introduction to its Physical Principles and Applications (American Institute of Physics, New York, 1989).

- Mackenzie, Nine-term equation for sound speed in the oceans, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 70, 807–812 (1982).

- C. C. Leroy, The speed of sound in pure and neptunian water, in Handbook of Elastic Properties of Solids, Liquids and Gases, edited by Levy, Bass & Stern, Volume IV: Elastic Properties of Fluids: Liquids and Gases (Academic Press, 2001)

- Wilson, Wayne D. (26 Jan 1959). "Speed of Sound in Distilled Water as a Function of Temperature and Pressure". J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 31 (8): 1067–1072. Bibcode:1959ASAJ...31.1067W. doi:10.1121/1.1907828. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- G. M. Wenz, Acoustic ambient noise in the ocean: spectra and sources, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 34, 1936–1956 (1962).

- S. C. Webb, The equilibrium oceanic microseism spectrum, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 92, 2141–2158 (1992).

- Gemba, Kay L.; Sarkar, Jit; Cornuelle, Bruce; Hodgkiss, William S.; Kuperman, W. A. (2018). "Estimating relative channel impulse responses from ships of opportunity in a shallow water environment". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 144 (3): 1231–1244. Bibcode:2018ASAJ..144.1231G. doi:10.1121/1.5052259. ISSN 0001-4966. PMID 30424623.

- R. H. Mellen, The Thermal-Noise Limit in the Detection of Underwater Acoustic Signals, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 24, 478–480 (1952).

- R. S. Dietz and M. J. Sheehy, Transpacific detection of myojin volcanic explosions by underwater sound. Bulletin of the Geological Society 2 942–956 (1954).

- M. A. McDonald, J. A. Hildebrand & S. M. Wiggins, Increases in deep ocean ambient noise in the Northeast Pacific west of San Nicolas Island, California, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 120, 711–718 (2006).

- Ocean Noise and Marine Mammals, National Research Council of the National Academies (The National Academies Press, Washington DC, 2003).

- R Chapman and J Harris, Surface backscattering Strengths Measured with Explosive Sound Sources. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 34, 547 (1962)

- K Mackenzie, Bottom Reverberation for 530 and 1030 cps Sound in Deep Water. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 36, 1596 (1964)

- J. R. Marshall and R. P. Chapman, Reverberation from a Deep Scattering Layer Measured with Explosive Sound Sources. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 36, 164 (1964)

- A. Milne, Underwater Backscattering Strengths of Arctic Pack Ice. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 36, 1551 (1964)

- MGS Station Data Listing and Report Catalog, Nav Oceanog Office Special Publication 142, 1974

- D.M.F. Chapman, D.D. Ellis, The elusive decibel – thoughts on sonars and marine mammals, Can. Acoust. 26(2), 29–31 (1996)

- W. J. Richardson, C. R. Greene, C. I. Malme and D. H. Thomson, Marine Mammals and Noise (Academic Press, San Diego, 1995).

- S. J. Parvin, E. A. Cudahy & D. M. Fothergill, Guidance for diver exposure to underwater sound in the frequency range 500 to 2500 Hz, Underwater Defence Technology (2002).

- Steevens CC, Russell KL, Knafelc ME, Smith PF, Hopkins EW, Clark JB (1999). "Noise-induced neurologic disturbances in divers exposed to intense water-borne sound: two case reports". Undersea Hyperb Med. 26 (4): 261–5. PMID 10642074. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - NATO Undersea Research Centre Human Diver and Marine Mammal Risk Mitigation Rules and Procedures, NURC Special Publication NURC-SP-2006-008, September 2006

- Fothergill DM, Sims JR, Curley MD (2001). "Recreational scuba divers' aversion to low-frequency underwater sound". Undersea Hyperb Med. 28 (1): 9–18. PMID 11732884. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved 2009-03-31.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - W. W. L. Au, The Sonar of Dolphins (Springer, NY, 1993).

- D. Simmonds & J. MacLennan, Fisheries Acoustics: Theory and Practice, 2nd edition (Blackwell, Oxford, 2005)

- Southall, B. L., Bowles, A. E., Ellison, W. T., Finneran, J. J., Gentry, R. L., Greene, C. R., ... & Richardson, W. J. (2007). Marine Mammal Noise Exposure Criteria Aquatic Mammals.

- Ladich, F., & Fay, R. R. (2013). Auditory evoked potential audiometry in fish. Reviews in fish biology and fisheries, 23(3), 317-364.

- Popper, A. N., Hawkins, A. D., Fay, R. R., Mann, D. A., Bartol, S., Carlson, T. J., ... & Løkkeborg, S. (2014). ASA S3/SC1. 4 TR-2014 Sound exposure guidelines for fishes and sea turtles: A technical report prepared by ANSI-Accredited standards committee S3/SC1 and registered with ANSI. Springer.

- McGrew, Kathleen A.; Crowell, Sarah E.; Fiely, Jonathan L.; Berlin, Alicia M.; Olsen, Glenn H.; James, Jennifer; Hopkins, Heather; Williams, Christopher K. (2022-10-15). "Underwater hearing in sea ducks with applications for reducing gillnet bycatch through acoustic deterrence". Journal of Experimental Biology. 225 (20). doi:10.1242/jeb.243953. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 36305674.

- Hansen, Kirstin Anderson; Maxwell, Alyssa; Siebert, Ursula; Larsen, Ole Næsbye; Wahlberg, Magnus (2017-05-05). "Great cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo) can detect auditory cues while diving". The Science of Nature. 104 (5): 45. Bibcode:2017SciNa.104...45H. doi:10.1007/s00114-017-1467-3. ISSN 1432-1904. PMID 28477271. S2CID 253640329.

- McGrew, Kathleen A.; Crowell, Sarah E.; Fiely, Jonathan L.; Berlin, Alicia M.; Olsen, Glenn H.; James, Jennifer; Hopkins, Heather; Williams, Christopher K. (2022-10-15). "Underwater hearing in sea ducks with applications for reducing gillnet bycatch through acoustic deterrence". Journal of Experimental Biology. 225 (20). doi:10.1242/jeb.243953. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 36305674.

- Zeyl, Jeffrey N.; Snelling, Edward P.; Connan, Maelle; Basille, Mathieu; Clay, Thomas A.; Joo, Rocío; Patrick, Samantha C.; Phillips, Richard A.; Pistorius, Pierre A.; Ryan, Peter G.; Snyman, Albert; Clusella-Trullas, Susana (2022-03-28). "Aquatic birds have middle ears adapted to amphibious lifestyles". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 5251. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.5251Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-09090-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8960762. PMID 35347167.

- D. B. Kilfoyle and A. B. Baggeroer, "The state of the art in underwater acoustic telemetry," IEEE J. Oceanic Eng. 25, 4–27 (2000).

- M.Stojanovic, "Acoustic (Underwater) Communications," entry in Encyclopedia of Telecommunications, John G. Proakis, Ed., John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

- Underwater Acoustic Positioning Systems, P.H. Milne 1983, ISBN 0-87201-012-0

- J. A. Nystuen, Listening to raindrops from underwater: An acoustic disdrometer, J Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 18(10), 1640–1657 (2001).

- R. D. Hill, Investigation of lightning strikes to water surfaces, J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 78, 2096–2099 (1985).

- Garrison 2012, p. 79.

- Kunzig 2000, pp. 40–41.

- Stewart 2009, p. 28.

- "Oceanography". Scholastic Teachers.

- "Tools of the Oceanographer". marinebio.net.

- "Technology used". noc.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2015-01-21. Retrieved 2015-01-21.

- Moore, A., T. Storeton-West, I. C. Russell, E. C. E. Potter, and M. J. Challiss. 1990. A technique for tracking Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) smolts through estuaries. International Council for the Ex- ploration of the Sea, C.M. 1990/M: 18, Copenhagen.

- D. Lohse, B. Schmitz & M. Versluis (2001). "Snapping shrimp make flashing bubbles" (PDF). Nature. 413 (6855): 477–478. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..477L. doi:10.1038/35097152. PMID 11586346. S2CID 4429684.

- S. Bevan, S. Danaher, J. Perkin, S. Ralph, C. Rhodes, L. Thompson, T. Sloane, D. Waters and The ACoRNE Collaboration, Simulation of ultra high energy neutrino induced showers in ice and water, Astroparticle Physics Volume 28, Issue 3, November 2007, Pages 366–379

Bibliography

- Garrison, Tom S. (1 August 2012). Essentials of Oceanography. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-8400-6155-3.

- Kunzig, Robert (17 October 2000). Mapping the Deep: The Extraordinary Story of Ocean Science. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-34535-3.

- Stewart, Robert H. (September 2009). Introduction to Physical Oceanography. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-1-61610-045-2.

Further reading

- Quality assurance of hydroacoustic surveys: the repeatability of fish-abundance and biomass estimates in lakes within and between hydroacoustic systems (free link to document)

- Hydroacoustics as a tool for assessing fish biomass and size distribution associated with discrete shallow water estuarine habitats in Louisiana

- Acoustic assessment of squid stocks

- Summary of the use of hydroacoustics for quantifying the escapement of adult salmonids (Oncorhynchus and Salmo spp.) in rivers. Ransom, B.H., S.V. Johnston, and T.W. Steig. 1998. Presented at International Symposium and Workshop on Management and Ecology of River Fisheries, University of Hull, England, 30 March-3 April 1998

- Multi-frequency acoustic assessment of fisheries and plankton resources. Torkelson,T.C., T.C. Austin, and P.H. Weibe. 1998. Presented at the 135th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and the 16th Meeting of the International Congress of Acoustics, Seattle, Washington.

- Acoustics Unpacked A great reference for freshwater hydroacoustics for resource assessment

- Inter-Calibration of Scientific Echosounders in the Great Lakes

- Hydroacoustic Evaluation of Spawning Red Hind Aggregations Along the Coast of Puerto Rico in 2002 and 2003

- Feasibility Assessment of Split-Beam Hydroacoustic Techniques for Monitoring Adult Shortnose Sturgeon in the Delaware River

- Categorising Salmon Migration Behaviour Using Characteristics of Split-beam Acoustic Data

- Evaluation of Methods to Estimate Lake Herring Spawner Abundance in Lake Superior

- Estimating Sockeye Salmon Smolt Flux and Abundance with Side-Looking Sonar

- Herring Research: Using Acoustics to Count Fish.

- Hydroacoustic Applications in Lake, River and Marine environments for study of plankton, fish, vegetation, substrate or seabed classification, and bathymetry.

- Hydroacoustics: Rivers (in: Salmonid Field Protocols Handbook: Chapter 4)

- Hydroacoustics: Lakes and Reservoirs (in: Salmonid Field Protocols Handbook: Chapter 5)

- PAMGUARD: An Open-Source Software Community Developing Marine Mammal Acoustic Detection and Localisation Software to Benefit the Marine Environment; https://web.archive.org/web/20070904035315/http://www.pamguard.org/home.shtml

External links

- Ultrasonics and Underwater Acoustics

- Monitoring the global ocean through underwater acoustics

- ASA Underwater Acoustics Technical Committee

- An Ocean of Sound

- Underwater Acoustic Communications

- Acoustic Communications Group at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

- Sound in the Sea

- SFSU Underwater Acoustics Research Group

- Discovery of Sound in the Sea

- Marine acoustics research