Zaza language

Zaza or Zazaki[5] (Zazaki: Zazakî, Kirmanckî, Kirdkî, Dimilkî)[lower-alpha 1][6] is a Northwestern Iranian language spoken primarily in eastern Turkey by the Zazas, who are commonly considered as Kurds, and in many cases identify as such.[7][8][9] The language is a part of the Zaza–Gorani language group of the northwestern group of the Iranian branch. The glossonym Zaza originated as a pejorative[10] and many Zazas call their language Dimlî.[11]

| Zaza | ||

|---|---|---|

| Zazakî / Kirmanckî / Kirdkî / Dimilkî | ||

| Native to | Turkey | |

| Region | Provinces of Sivas, Tunceli, Bingöl, Erzurum, Erzincan, Elazığ, Muş, Malatya,[1] Adıyaman and Diyarbakır[1] | |

| Ethnicity | Zazas | |

Native speakers | 3–4 million (2009)[1] | |

| Latin script | ||

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-2 | zza | |

| ISO 639-3 | zza – inclusive codeIndividual codes: kiu – Kirmanjki (Northern Zaza)diq – Dimli (Southern Zaza) | |

| Glottolog | zaza1246 | |

| ELP | Dimli | |

| Linguasphere | 58-AAA-ba | |

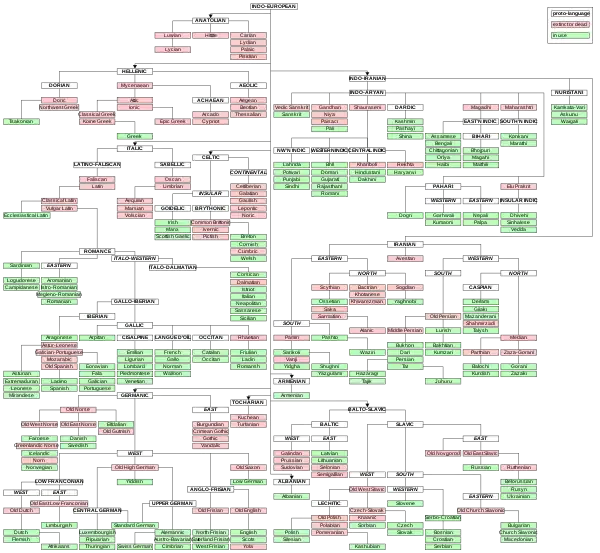

The position of Zazaki among Iranian languages[4]

| ||

Zaza is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | ||

According to Ethnologue, Zaza is spoken by around three to four million people.[1] Nevins, however, puts the number of Zaza speakers between two and three million.[12]

Relations to other languages

In terms of grammar, genetics, linguistics and vocabulary Zazaki is closely related to Talysh, Old Azeri, Tati, Sangsari, Semnani, Mazandarani and Gilaki languages spoken on the shores of the Caspian Sea and central Iran.[13][14] Ludwig Paul demonstrated that Zazaki is closely related to Old Azeri, Talysh and Parthian (an extinct northwestern Iranian language), shares many similarities with these languages[15] and does not have universal Kurdish vowel changes.[16] According to the head of the Paris Kurdish Institute, linguist Prof. Dr. Joyce Blau, Zazaki is a separate language and the history of Zazaki is older than that of Kurdish.[17][18] Zaza is linguistically more closely related to Gorani, Gilaki, Talysh, Tati, Mazandarani and the Semnani language.[13] Due to centuries of interaction, Kurmanji has had an impact on the language, which have blurred the boundaries between the two languages.[19] This and the fact that Zaza speakers are identified as ethnic Kurds by some scholars,[20][21] has encouraged some linguists to classify the language as a Kurdish dialect.[22][23]

History

Writing in Zaza is a recent phenomenon. The first literary work in Zaza is Mewlîdu'n-Nebîyyî'l-Qureyşîyyî by Ehmedê Xasi in 1899, followed by the work Mawlûd by Osman Efendîyo Babij in 1903. As the Kurdish language was banned in Turkey during a large part of the Republican period, no text was published in Zaza until 1963. That year saw the publication of two short texts by the Kurdish newspaper Roja Newe, but the newspaper was banned and no further publication in Zaza took place until 1976, when periodicals published a few Zaza texts. Modern Zaza literature appeared for the first time in the journal Tîrêj in 1979 but the journal had to close as a result of the 1980 coup d'état. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, most Zaza literature was published in Germany, France and especially Sweden until the ban on the Kurdish language was lifted in Turkey in 1991. This meant that newspapers and journals began publishing in Zaza again. The next book to be published in Zaza (after Mawlûd in 1903) was in 1977, and two more books were published in 1981 and 1986. From 1987 to 1990, five books were published in Zaza. The publication of books in Zaza increased after the ban on the Kurdish language was lifted and a total of 43 books were published from 1991 to 2000. As of 2018, at least 332 books have been published in Zaza.[24]

Due to the above-mentioned obstacles, the standardization of Zaza could not have taken place and authors chose to write in their local or regional Zaza variety. In 1996, however, a group of Zaza-speaking authors gathered in Stockholm and established a common alphabet and orthographic rules which they published. Some authors nonetheless do not abide by these rules as they do not apply the orthographic rules in their oeuvres.[25]

In 2009, Zaza was classified as a vulnerable language by UNESCO.[26]

The institution of Higher Education of Turkey approved the opening of the Zaza Language and Literature Department in Munzur University in 2011 and began accepting students in 2012 for the department. In the following year, Bingöl University established the same department.[27] TRT Kurdî also broadcast in the language.[28] Some TV channels which broadcast in Zaza were closed after the 2016 coup d'état attempt.[29]

Dialects

There are two main Zaza dialects:

- Northern Zaza [kiu]: It is spoken in Tunceli, Erzincan, Erzurum, Sivas, Gümüşhane, Muş, and Kayseri provinces.

Its subdialects are:

- Southern Zaza [diq]: It is spoken in primarily Bingöl, Çermik, Dicle, Eğil, Gerger, Palu and Hani, Turkey.

Its subdialects are:

- Sivereki, Kori, Hazzu, Motki, Dumbuli, Eastern/Central Zazaki, Dersimki.

Zaza shows many similarities with other Northwestern Iranian languages:

- Similar personal pronouns and use of these[31]

- Enclitic use of the letter "u"[31]

- Very similar ergative structure[32]

- Masculine and feminine ezafe system[33]

- Both languages have nominative and oblique cases that differs by masculine -î and feminine -ê

- Both languages have forgotten possessive enclitics, while it exists in such other languages as Persian, Sorani, Gorani, Hewrami or Shabaki

- Both languages distinguish between aspirated and unaspirated voiceless stops

- Similar vowel phonemes

Ludwig Paul divides Zaza into three main dialects. In addition, there are transitions and edge accents that have a special position and cannot be fully included in any dialect group.[34]

Grammar

| Pronoun | Zaza | Talysh [35] | Tati[36][37] | Semnani[38] | Sangsari[39] | Ossetian[40] | Persian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st sing. | ez | āz | āz | ā | ā | æz (az) | man | I |

| 2nd | tı | te/ti | ti | ti | ti | dɨ (di) | to | you |

| 3rd | o/ey | ay | u | un | no | wuiy | ū, ān | he |

| 3rd | a/ay | - | nā | una | na | - | - | she |

| 1st plur. | ma | ama | amā | hamā | mā | max | mā | we |

| 2nd | şıma | shēma/shūma | shūmā | shūmā | shūmā | shimax | shomā | you |

| 3rd. | ê, i, ina, ino | ayēn | ē | e | ey | idon/widon | ēnan, ishān, inhā | they |

As with a number of other Iranian languages like Talysh,[41] Tati,[14][42] central Iranian languages and dialects like Semnani, Kahangi, Vafsi,[43] Balochi[44] and Kurmanji, Zaza features split ergativity in its morphology, demonstrating ergative marking in past and perfective contexts, and nominative-accusative alignment otherwise. Syntactically it is nominative-accusative.[45]

Grammatical gender

Among all Western Iranian languages Zaza, Semnani,[46][47][48] Sangsari,[49] Tati,[50][51] central Iranian dialects like Cālī, Fārzāndī, Delījanī, Jowšaqanī, Abyāne'i[52] and Kurmanji distinguish between masculine and feminine grammatical gender. Each noun belongs to one of those two genders. In order to correctly decline any noun and any modifier or other type of word affecting that noun, one must identify whether the noun is feminine or masculine. Most nouns have inherent gender. However, some nominal roots have variable gender, i.e. they may function as either masculine or feminine nouns.[53]

Phonology

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɨ | u |

| ʊ | |||

| Mid | e | ə | o |

| Open | ɑ |

The vowel /e/ may also be realized as [ɛ] when occurring before a consonant. /ɨ/ may become lowered to [ɪ] when occurring before a velarized nasal /n/ [ŋ], or occurring between a palatal approximant /j/ and a palato-alveolar fricative /ʃ/. Vowels /ɑ/, /ɨ/, or /ə/ become nasalized when occurring before /n/, as [ɑ̃], [ɨ̃], and [ə̃], respectively.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Palato- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | phar. | |||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | (ŋ) | |||||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | tˁ | t͡ʃ | k | q | |||

| voiced | b | d | d͡ʒ | ɡ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | sˤ | ʃ | x | ħ | h | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | ɣ | ʕ | |||||

| Rhotic | tap/flap | ɾ | ||||||||

| trill | r | |||||||||

| Lateral | central | l | ||||||||

| velarized | ɫ | |||||||||

| Approximant | w | j | ||||||||

/n/ becomes a velar [ŋ] when following a velar consonant.[54][55]

Alphabet

The Zaza alphabet is an extension of the Latin alphabet used for writing the Zaza language, consisting of 32 letters, six of which (ç, ğ, î, û, ş, and ê) have been modified from their Latin originals for the phonetic requirements of the language.[56]

| Upper case | A | B | C | Ç | D | E | Ê | F | G | Ğ | H | I[upper-alpha 1] | Î[upper-alpha 1] | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | Ş | T | U | Û | V | W | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower case | a | b | c | ç | d | e | ê | f | g | ğ | h | i [upper-alpha 1] | î [upper-alpha 1] | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | s | ş | t | u | û | v | w | x | y | z |

| IPA phonemes | a | b | d͡ʒ | t͡ʃ | d | ɛ | e | f | g | ɣ | h | ɨ | i | ʒ | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r, ɾ | s | ʃ | t | ʊ | u | v | w | x | j | z |

- Zaza Wikipedia uses ⟨I/ı⟩ and ⟨İ/i⟩ instead of both I's in the table.

Gallery

References

- Zaza at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

Kirmanjki (Northern Zaza) at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

Dimli (Southern Zaza) at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- "Multitree | The LINGUIST List". linguistlist.org. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- "Glottolog 4.5 - Zaza". glottolog.org. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- "worldhistory". titus.fkidg1.uni-frankfurt.de. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- Kenstowicz, Michael J. (2004). Studies in Zazaki Grammar. MITWPL.

- Lezgîn, Roşan (26 August 2009). "Kirmanckî, Kirdkî, Dimilkî, Zazakî". Zazaki.net (in Zazaki). Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Michiel Leezenberg (1993). "Gorani Influence on Central Kurdish: Substratum or Prestige Borrowing?" (PDF). ILLC - Department of Philosophy, University of Amsterdam.

- "Minority Rights Group International (MRG)-Minorities-Kurds".

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan (7 May 2015). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. ISBN 9781138869745.

- Arakelova, Victoria (1999). "The Zaza People as a New Ethno-Political Factor in the Region". Iran & the Caucasus. 3/4: 397–408. doi:10.1163/157338499X00335. JSTOR 4030804.

- Asatrian, Garnik (1995). "DIMLĪ". Encyclopedia Iranica. VI. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- Anand, Pranav; Nevins, Andrew (2004). "Shifty Operators in Changing Contexts". In Young, Robert B. (ed.). Proceedings of the 14th Semantics and Linguistic Theory Conference held May 14–16, 2004, at Northwestern University. p. 36. doi:10.3765/salt.v14i0.2913.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Ehsan Yar-Shater (1990). Iranica Varia: Papers in Honor of Professor Ehsan Yarshater. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 267. ISBN 90-6831-226-X.

- Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- Paul, L. (1998). The position of Zazaki among West Iranian languages. Old and Middle Iranian Studies, 163-176.

- Elfenbein, J. (2000). Zazaki: Grammatik und Versuch einer Dialektologie. By Ludwig Paul. pp. xxi, 366. Wiesbaden, Reichert Verlag, 1999. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 10(2), 255-257. p. 255

- "Zazaca Kürtçe'den Daha Eski Bir Dildir". Dersim News. 25 January 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- "Zazaca Kürtçe'den çok daha eski bir dil". siverekhaber.com/. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- Garry, Jane; Rubino, Carl R. Galvez (2001). Facts About the World's Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World's Major Languages, Past and Present. New York: H. W. Wilson. p. 398. ISBN 0-8242-0970-2.

- van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (28 January 2009). "Is Ankara Promoting Zaza Nationalism to Divide the Kurds?". The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Kaya, Mehmed S. (2011). The Zaza Kurds of Turkey: A Middle Eastern Minority in a Globalised Society. London: Tauris Academic Studies. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-84511-875-4.

- According to the linguist Jacques Leclerc of Canadian "Laval University of Quebec, Zazaki is a part of Kurdish languages, Zaza are Kurds, he also included Goura/Gorani as Kurds "Turquie : situation générale". tlfq.ulaval.ca (in French). Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- T.C. Millî Eğitim Bakanlığı, Talim Ve Terbiye Kurulu Başkanlığı (2012). Ortaokul Ve İmam Hatip Ortaokulu Yaşayan Diller Ve Lehçeler Dersi (Kürtçe; 5. Sınıf) Öğretim Programı (PDF) (in Turkish). Ankara. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2012.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link), "Bu program ortaokul 5, 6, 7, ve 8. sınıflar seçmeli Kürtçe dersinin ve Kürtçe’nin iki lehçesi Kurmancca ve Zazaca için müşterek olarak hazırlanmıştır. Program metninde geçen “Kürtçe” kelimesi Kurmancca ve Zazaca lehçelerine birlikte işaret etmektedir." - Malmîsanij (2021), pp. 675–676.

- Malmîsanij (2021), pp. 676–677.

- Malmîsanij (2021), p. 681.

- Erdoğmuş, Hatip; Orki̇n, Şeyhmus (2018). "Bingöl ve Munzur Üniversitesinde Açılan Zaza Dili ve Edebiyatı Bölümleri ve Bu Bölümlerin Üniversitelerine Katkıları". Kent Akademisi (in Turkish). 11 (1): 164.

- Tabak, Husrev (2017). The Kosovar Turks and Post-Kemalist Turkey: Foreign Policy, Socialisation and Resistance. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-78453-737-1.

- Malmîsanij (2021), p. 679.

- Prothero, W. G. (1920). Armenia and Kurdistan. London: H. M. Stationery Office. p. 19. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- Johanson, Lars; Bulut, Christiane (2006). Turkic-Iranian Contact Areas: Historical and Linguistic Aspects. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 293. ISBN 3-447-05276-7.

- Ludwig Windfuhr, Gernot (2009). The Iranian Languages. London: Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-7007-1131-4.

- Kahnemuyipour, Arsalan (7 October 2016). "The Ezafe Construction: Persian and Beyond" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2019 – via iub.edu.

- Paul, Ludwig (1998). Zazaki – Versuch einer Dialektologie (in German). Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag.

- Wolfgang, Schulze: Northern Talysh. Lincom Europa. 2000. (page 35)

- مفيدي روح اله. تحول نظام واژه بستي در فارسي ميانه و نو.

- Sabzalipour, J., & Vaezi, H. (2018). The study of clitics in Tati Language (Deravi variety).

- احمدی پناهی سمنانی، محمد (۱۳۷۴). آداب رسوم مردم سمنانی. نشر پژوهشگاه علوم انسانی و مطالعات فرهنگی. ص. ۴۰–۴۴.

- Pierre Lecoq. 1989. "Les dialectes caspiens et les dialectes du nord-ouest de l'Iran," Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum. Ed. Rüdiger Schmitt. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. Pages 296–314.

- Oranskij, Iosif Mikhailovich. “Zabānhā ye irani [Iranian languages]”. Translated by Ali Ashraf Sadeghi. Sokhan publication (2007).

- Mirdehghan, M., & Nourian, G. Ergative Case Marking and Agreement in the Central Dialect of Talishi.

- Ergative in Tāti Dialect of Khalkhāl, Jahandust Sabzalipoor

- Koohkan, Sepideh. The typology of modality in modern West Iranian languages. 2019. PhD Thesis. University of Antwerp.

- Agnes Korn. The Ergative System in Balochi from a Typological Perspective. Iranian Journal of Applied Language Studies, 2009, 1, pp.43-79. ffhal-01340943

- Haig, Geoffrey L. J. (2004). Alignment in Kurdish: A Diachronic Perspective (PDF) (Habilitation thesis). Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Mohammad- Ebrahimi, Z. et. al. (2010). “The study of grammatical gender in Semnani dialect”. Papers of the First International Conference on Iran’s Desert Area Dialects. Pp. 1849-1876.

- Seraj, F. (2008). The Study of Gender, its Representation & Nominative and accusative cases in Semnani Dialect. M. A. thesis in Linguistics, Tehran: Payame- Noor University.

- Rezapour, Ebrahim (2015). "Word order in Semnani language based on language typology". IQBQ. 6 (5): 169-190

- Borjian, H. (2021). Essays on Three Iranian Language Groups: Taleqani, Biabanaki, Komisenian (Vol. 99). ISD LLC.

- Vardanian, A. (2016). Grammatical gender in New Azari dialects of Šāhrūd. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 79(3), 503 511.

- A Morpho-phonological Analysis of Vowel Changes in Takestani-Tati Verb Conjugations: Assimilation, Deletion, and Vowel Harmony

- H. Rezai Baghbidi (ed.), Exploring grammatical gender in New Iranian languages and dialects, proceedings of the First Seminar of Iranian Dialectology, 29 April-1 May 2001, Tehran, Department of Dialectology, Academy of Persian Language and Literature, 2003.

- Todd, Terry Lynn (2008). A Grammar of Dimili (also Known as Zaza) (PDF). Electronic Publication. p. 33. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2012.

- Ludwig, Paul (2009). Zazaki. The Iranian Languages: London & New York: Routledge. pp. 545–586.

- Todd, Terry Lynn (2008). A Grammar of Dimili (also Known as Zaza). Stockholm: Iremet.

- Çeko Kocadag (2010). Ferheng Kirmanckî (zazakî – Kurmancî) – Kurmancî – Kirmanckî (zazakî). Berlin: Weşanên Komkar. ISBN 978-3-927213-40-1.

- "worldhistory". worldhistory.com by Multiple authors. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- "worldhistory". titus.fkidg1.uni-frankfurt.de. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- These exact names also appear in Northern Kurdish.

Literature

- Arslan, İlyas. 2016. Verbfunktionalität und Ergativität in der Zaza-Sprache. Dissertation, Universität Düsseldorf.

- Blau, Gurani et Zaza in R. Schmitt, ed., Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden, 1989, ISBN 3-88226-413-6, pp. 336–40 (About Daylamite origin of Zaza-Guranis)

- Gajewski, Jon. (2004) "Zazaki Notes" Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Gippert, Jost. (1996) "Historical Development of Zazaki" University of Frankfurt

- Haig, Geoffrey. and Öpengin, Ergin. "Introduction to Special Issue Kurdish: A critical research overview" Archived 22 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine University of Bamberg, Germany

- Larson, Richard. and Yamakido, Hiroko. (2006) "Zazaki as Double Case-Marking" Stony Brook University and University of Arizona.

- Lynn Todd, Terry. (1985) "A Grammar of Dimili" University of Michigan

- Mesut Keskin, Zur dialektalen Gliederung des Zazaki. Magisterarbeit, Frankfurt 2008. Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (PDF)

- Malmîsanij, Mehemed (2021). "The Kirmanjki (Zazaki) Dialect of Kurdish Language and the Issues it Faces". In Bozarslan, Hamit; Gunes, Cengiz; Yadirgi, Veli (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Kurds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 663–684. doi:10.1017/9781108623711.027. ISBN 978-1-108-62371-1. S2CID 235541104.

- Paul, Ludwig. (1998) "The Position of Zazaki Among West Iranian languages" University of Hamburg

- Werner, Brigitte . (2007) "Features of Bilingualism in the Zaza Community" Archived 29 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine Marburg, Germany

See also

Further reading

- Henarek – Granatäpfelchen: Welat Şêrq ra Sonîk | Märchen aus dem Morgenland. Gesammelt und verfasst von Suphi Aydin. Hamburg: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2022. ISBN 978-3-929728-89-7.

External links

- Zaza People and Zazaki Literature

- News, Articles and Columns (in Zaza)

- News, Folktales, Grammar Course Archived 29 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in Zaza)

- News, Articles and Bingöl city (in Zaza)

- Center of Zazaki (in Zaza, German, Turkish, and English)

- Website of Zazaki Institute Frankfurt

- "Zaza a Northwestern Iranic language of eastern Turkey". Endangered Language Alliance.