Nail–patella syndrome

Nail–patella syndrome is a genetic disorder that results in small, poorly developed nails and kneecaps, but can also affect many other areas of the body, such as the elbows, chest, and hips. The name "nail–patella" can be very misleading because the syndrome often affects many other areas of the body, including even the production of certain proteins.[1]: 666 Those affected by NPS may have one or more affected areas of the body, and its severity varies depending on the individual. It is also referred to as iliac horn syndrome, hereditary onychoosteodysplasia (HOOD syndrome), Fong disease or Turner–Kieser syndrome.[2]

| Nail–patella syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | NPS |

| |

| Nail of a patient with nail–patella syndrome | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Diagnosis of NPS can be made at birth but is common for it to remain undiagnosed for several generations. While there is no cure available for NPS, treatment is available and recommended.

Signs and symptoms

The skeletal structures of individuals who have this disorder may have pronounced deformities. As reported by several medical doctors, the following features are commonly found in people who with nail–patella syndrome:[3]

Bones and joints

- Patellar involvement is present in approximately 90% of patients; however, patellar aplasia occurs in only 20%.

- In instances in which the patellae are smaller or luxated, the knees may be unstable.

- The elbows may have limited motion (e.g., limited pronation, supination, extension).

- Subluxation of the radial head may occur.

- Arthrodysplasia of the elbows is reported in approximately 90% of patients.

- General hyperextension of the joints can be present.

- Exostoses arising from the posterior aspect of the iliac bones ("iliac horns") are present in as many as 80% of patients; this finding is considered pathognomonic for the syndrome.

- Other reported bone changes include scoliosis, scapular hypoplasia, and the presence of cervical ribs.

_Elbow1.JPG.webp) An elbow of a man with nail–patella syndrome (NPS)

An elbow of a man with nail–patella syndrome (NPS) This is a view from a different angle of the same man's other elbow

This is a view from a different angle of the same man's other elbow

Glaucoma is also closely associated with nail-patella, specifically open-angled glaucoma (OAG). Side affects may include frequent headaches, blurred vision, or total vision loss. This occurs gradually over time and symptoms may not be evident in children.[4]

Kidney issues may arise such as deposition of protein in the urine and nephritis. Proteinuria is usually the first sign of kidney involvement. It can reveal itself either rapidly or years after having asymptomatic deposition of protein in the urine, kidney failure occurs in around 5% of NPS patients. Hypothyroidism, irritable bowel syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and thin tooth enamel are associated with NPS, but whether these are related or simply coincidences are unclear.[5]

Genetics

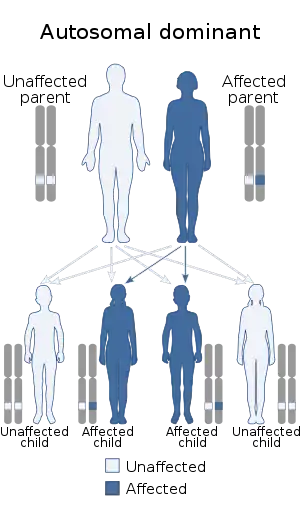

Nail–patella syndrome is inherited via autosomal dominancy linked to aberrancy on human chromosome 9's q arm (the longer arm), 9q34. This autosomal dominancy means that only a single copy, instead of both, is sufficient for the disorder to be expressed in the offspring, meaning the chance of getting the disorder from an affected heterozygous parent is 50%. The frequency of the occurrence is 1/50,000. The disorder is linked to the ABO blood group locus.

It is associated with random mutations in the LMX1B gene. Studies have been conducted and 83 mutations of this gene have been identified.[6][7][8]

Diagnosis

The hallmark features of this syndrome are poorly developed fingernails, toenails, and patellae (kneecaps). Sometimes, this disease causes the affected person to have either no thumbnails or a small piece of a thumbnail on the edge of the thumb. The lack of development or complete absence of fingernails results from the loss of function mutations in the LMX1B gene. This mutation may cause a reduction in dorsalising signals, which then results in the failure to normally develop dorsal specific structures such as nails and patellae.[9] Other common abnormalities include elbow deformities, abnormally shaped pelvic (hip) bones, and kidney disease.

Treatment

Treatment for NPS varies depending on the symptoms observed.

- Perform screening for kidney disease and glaucoma, surgery, intensive physiotherapy, or genetic counseling.[6]

- ACE inhibitors are taken to treat proteinuria and hypertension in NPS patients.[10][11]

- Dialysis and kidney transplant.[12][13]

- Physical therapy, bracing and analgesics for joint pain.

See also

References

- Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. Page 786-7. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- Choczaj-Kukula, A., & Janniger, C. K. (2009). Nail–patella syndrome. In emedicine: WebMD. Retrieved October 11, 2009, from WebMD database.

- Romero, P., Sanhueza, F., Lopez, P., Reyes, L., & Herrera, L. (2011). C.194 a>C (Q65P) mutation in the LMX1B gene in patients with nail-patella syndrome associated with glaucoma. Molecular Vision, 17(210-11), 1929–1939.

- Buatti Chris (August 2007). "Nail-Patella Syndrome". Consultant 360. 47 (8).

- Sweeney E, Fryer A (March 2003). "Nail patella syndrome: a review of the phenotype aided by developmental biology". Journal of Medical Genetics. 40 (3): 153–162. doi:10.1136/jmg.40.3.153. PMC 1735400. PMID 12624132.

- Towers AL, Clay CA, Sereika SM, McIntosh I, Greenspan SL (April 2005). "Skeletal integrity in patients with nail patella syndrome". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90 (4): 1961–5. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-0997. PMID 15623820.

- Romero P.; Sanhueza F.; Lopez P.; Reyes L.; Herrera L. (2011). "c.194 A>C (Q65P) mutation in the LMX1B gene in patients with nail-patella syndrome associated with glaucoma". Molecular Vision. 17: 1929–39. PMC 3154131. PMID 21850167.

- Wright M J (September 2000). "Achondroplasia and nail-patella syndrome: the compound phenotype". Journal of Medical Genetics. 37 (9): 25e–25. doi:10.1136/jmg.37.9.e25. PMC 1734684. PMID 10978372.

- Kaplan's Essentials of Cardiac Anesthesia. Elsevier. 2018. doi:10.1016/c2012-0-06151-0. ISBN 978-0-323-49798-5.

- Aronow, Wilbert S. (2010). "Cardiac Arrhythmias". Brocklehurst's Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. Elsevier. pp. 327–337. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4160-6231-8.10045-5. ISBN 978-1-4160-6231-8.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors ACE inhibitors have been demonstrated to reduce sudden cardiac death in some studies of persons with CHF.24,56

- "Overview and Types of Dialysis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- "20 Common Kidney Transplant Questions and Answers". National Kidney Foundation. 26 January 2017. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.