Pulmonary venoocclusive disease

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) is a rare form of pulmonary hypertension caused by progressive blockage of the small veins in the lungs.[2] The blockage leads to high blood pressures in the arteries of the lungs, which, in turn, leads to heart failure. The disease is progressive and fatal, with median survival of about 2 years from the time of diagnosis to death.[3] The definitive therapy is lung transplantation.[4]

| Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Obstructive disease of the pulmonary veins[1] |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease-Intimal fibrosis with marked narrowing of lumen of a large pulmonary vein | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology, cardiology |

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, fatigue[2] |

| Causes | Narrow pulmonary vein, Pulmonary artery hypertension[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Chest x-ray, Chest CT[2] |

| Treatment | Vasodilators can be used[2] |

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms for pulmonary veno-occlusive disease are the following:[2][5]

- Shortness of breath

- Fatigue

- Fainting

- Hemoptysis

- Difficulty breathing ( lying flat)

- Chest pain

- Cyanosis

- Hepatosplenic congestion

Cause

The genetic cause of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease is mutations in EIF2AK4 gene. Though this does not mean other possible causes do not exist, such as viral infection and risk of toxic chemicals (chemotherapy drugs).[6]

Pathophysiology

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease may have a genetic basis. Published reports have indicated fatal occurrences that appeared to possess a familial pattern, more to the point, a germline mutation.[7] The pathophysiology of veno-occlusive disease culminates in occlusion of the pulmonary blood vessels. This could be due to edematous tissue (sclerotic fibrous tissue). Thickening is identified in lobular septal veins, also dilatation of lymphatics happens. Furthermore, alveolar capillaries become dilated (due to back-pressure).[8]

Diagnosis

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease can only be well diagnosed with a lung biopsy. CT scans may show characteristic findings such as ground-glass opacities in centrilobular distribution, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, but these findings are non-specific and may be seen in other conditions. However, pulmonary hypertension (revealed via physical examination), in the presence of pleural effusion (done via CT scan) usually indicates a diagnosis of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. The prognosis indicates usually a 2-year (24 month) life expectancy after diagnosis.[9][10]

Treatment

Treatments for primary pulmonary hypertension such as prostacyclins and endothelin receptor antagonists can be fatal in people with PVOD due to the development of severe pulmonary edema, and worsening symptoms after initiation of these medications may be a clue to the diagnosis of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease.[7]

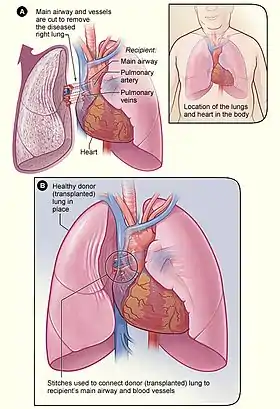

The definitive therapy is lung transplantation, though transplant rejection is always a possibility, in this measures must be taken in terms of appropriate treatment and medication.[11][12]

Epidemiology

Pulmonary venoocclusive disease is rare, difficult to diagnose, and probably frequently misdiagnosed as idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Prevalence in parts of Europe is estimated to be 0.1-0.2 cases per million.[13]

PVOD appears to occur as frequently in men as in women, and age at diagnosis ranges from 7–74 years with a median of 39 years.[13] PVOD may occur in patients with associated diseases such as HIV, bone marrow transplantation, and connective tissue diseases.[13] PVOD has also been associated with several chemotherapy regimens such as bleomycin, BCNU, and mitomycin.[13]

References

- "Pulmonary venoocclusive disease | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- "Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-07.

- Escribano (2012). "Survival in pulmonary hypertension in Spain: insights from the Spanish registry". Eur Respir J. 40 (3): 596–603. doi:10.1183/09031936.00101211. PMID 22362843.

- Ye (2011). "Lengthy Diagnostic Challenge in a Rare Case of Pulmonary Veno-Occlusive Disease: Case Report and Review of the Literature". Intern Med. 50 (12): 1323–7. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5035. PMID 21673470.

- Zander, Dani S.; Farver, Carol F. (2008-01-01). Pulmonary Pathology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-443-06741-9.

- "Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease". Genetics Home Reference. 2015-11-02. Retrieved 2015-11-07.

- Montani, David (2010). "Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease: Recent progress and current challenges". Respiratory Medicine. 104: S23–S32. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2010.03.014. PMID 20456932.

- "Pulmonary Veno-Occlusive Disease: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". 2018-10-30.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Light, Richard W. (2007-01-01). Pleural Diseases. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 128. ISBN 9780781769570.

- Grosse, Claudia; Grosse, Alexandra (2010-11-01). "CT Findings in Diseases Associated with Pulmonary Hypertension: A Current Review". RadioGraphics. 30 (7): 1753–1777. doi:10.1148/rg.307105710. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 21057119.

- "Pulmonary Veno-Occlusive Disease Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Specific PAH Therapies, Immunosuppressants, Steroids, and Antithrombotic Agents". 2018-10-30.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Lung Transplantation: MedlinePlus". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-07.

- Montani (2009). "Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease". Eur Respir J. 33 (1): 189–200. doi:10.1183/09031936.00090608. PMID 19118230.

- Phull, Hardeep (July 26, 2016). "She's tethered to an oxygen tank, but her singing career is soaring". New York Post.

- Insdorf, Annette (November 10, 2013). "The Challenges of Chloe Temtchine". The Huffington Post.

Further reading

- Montani, David; Lau, Edmund M.; Dorfmüller, Peter; Girerd, Barbara; Jaïs, Xavier; Savale, Laurent; Perros, Frederic; Nossent, Esther; Garcia, Gilles; Parent, Florence; Fadel, Elie; Soubrier, Florent; Sitbon, Olivier; Simonneau, Gérald; Humbert, Marc (2016). "Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease". The European Respiratory Journal. 47 (5): 1518–1534. doi:10.1183/13993003.00026-2016. ISSN 1399-3003. PMID 27009171.

- Lung Diseases—Advances in Research and Treatment: 2013 Edition. ScholarlyEditions. 2013-06-21. ISBN 9781481677332.

- Mandel, Jess; Mark, Eugene J.; Hales, Charles A. (2000-11-01). "Pulmonary Veno-occlusive Disease". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 162 (5): 1964–1973. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.162.5.9912045. ISSN 1073-449X. PMID 11069841.