Raynaud syndrome

Raynaud syndrome, also known as Raynaud's phenomenon, eponymously named after the physician Auguste Gabriel Maurice Raynaud, who first described it in his doctoral thesis in 1862, is a medical condition in which the spasm of small arteries causes episodes of reduced blood flow to end arterioles.[1] Typically, the fingers, and less commonly, the toes, are involved.[1] Rarely, the nose, ears, or lips are affected.[1] The episodes classically result in the affected part turning white and then blue.[2] Often, numbness or pain occurs.[2] As blood flow returns, the area turns red and burns.[2] The episodes typically last minutes but can last several hours.[2]

| Raynaud syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Raynaud's, Raynaud's disease, Raynaud's phenomenon, Raynaud's syndrome[1] |

| |

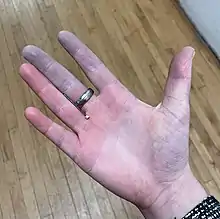

| The hand of a person with Raynaud syndrome during an attack. | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Rheumatology |

| Symptoms | An affected part turning white, then blue, then red, burning[2] |

| Complications | skin sores, gangrene[2] |

| Usual onset | 15–30 year old, typically females[3][4] |

| Duration | Up to several hours per episode[2] |

| Risk factors | Cold, emotional stress[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on the symptoms[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Causalgia, erythromelalgia[5] |

| Treatment | Avoiding cold, calcium channel blockers, iloprost[3] |

| Frequency | 4% of people[3] |

Episodes are typically triggered by cold or emotional stress.[2] Primary Raynaud's, also known as idiopathic, means that it is spontaneous, of unknown cause, and unrelated to another disease. Secondary Raynaud's occurs as a result of another condition and has an older age at onset; episodes are intensely painful and can be asymmetric and associated with skin lesions.[3] Secondary Raynaud's can occur due to a connective-tissue disorder such as scleroderma or lupus, injuries to the hands, prolonged vibration, smoking, thyroid problems, and certain medications, such as birth control pills.[6] Diagnosis is typically based on the symptoms.[3]

The primary treatment is avoiding the cold.[3] Other measures include the discontinuation of nicotine or stimulant use.[3] Medications for treatment of cases that do not improve include calcium channel blockers and iloprost.[3] Little evidence supports alternative medicine.[3] Severe disease may in rare cases lead to complications, specifically skin sores or gangrene.[2]

About 4% of people have the condition.[3] Onset of the primary form is typically between ages 15 and 30 and occurs more frequently in females.[3][4] The secondary form usually affects older people.[4] Both forms are more common in cold climates.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The condition can cause localized pain, discoloration (paleness), and sensations of cold and/or numbness.

When exposed to cold temperatures, the blood supply to the fingers or toes, and in some cases the nose or earlobes, is markedly reduced; the skin turns pale or white (called pallor) and becomes cold and numb. These events are episodic, and when the episode subsides or the area is warmed, the blood flow returns, and the skin color first turns red (rubor), and then back to normal, often accompanied by swelling, tingling, and a painful "pins and needles" sensation. All three color changes are observed in classic Raynaud's. However, not all patients see all of the aforementioned color changes in all episodes, especially in milder cases of the condition. The red flush is due to reactive hyperemia of the areas deprived of blood flow.

In pregnancy, this sign normally disappears due to increased surface blood flow. Raynaud's has occurred in breastfeeding mothers, causing nipples to turn white and painful.[7]

Causes

Primary

Raynaud's disease, or primary Raynaud's, is diagnosed if the symptoms are idiopathic, that is, if they occur by themselves and not in association with other diseases. Some refer to primary Raynaud's disease as "being allergic to coldness". It often develops in young women in their teens and early adulthood. Primary Raynaud's is thought to be at least partly hereditary, although specific genes have not yet been identified.[8]

Smoking increases frequency and intensity of attacks, and a hormonal component exists. Caffeine, estrogen, and nonselective beta-blockers are often listed as aggravating factors, but evidence that they should be avoided is not solid.[9]

Secondary

Raynaud's phenomenon, or secondary Raynaud's, occurs secondary to a wide variety of other conditions.

Secondary Raynaud's has a number of associations:

- Connective tissue disorders:

- Eating disorders:

- Obstructive disorders:

- Drugs:

- Beta-blockers

- Cytotoxic drugs – particularly chemotherapeutics and most especially bleomycin

- Cyclosporin

- Bromocriptine

- Ergotamine

- Sulfasalazine

- Anthrax vaccines whose primary ingredient is the Anthrax Protective Antigen

- Stimulant medications, such as those used to treat ADHD (amphetamine and methylphenidate)[11]

- OTC pseudoephedrine medications (Chlor-Trimeton, Sudafed, others)[12]

- Occupation:

- Jobs involving vibration, particularly drilling and prolonged use of a string trimmer (weed whacker), experience vibration white finger

- Exposure to vinyl chloride, mercury

- Exposure to the cold (e.g., by working as a frozen food packer)

- Others:

- Physical trauma to the extremities

- Lyme disease

- Hypothyroidism

- Cryoglobulinemia

- Cancer

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Reflex sympathetic dystrophy

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Magnesium deficiency

- Multiple sclerosis

- Erythromelalgia (clinically presenting as the opposite of Raynaud's, with hot and warm extremities, often co-exists in patients with Raynaud's[13])

- Chilblains (also clinically presenting as the opposite of Raynaud's, with hot and itchy extremities, however it affects smaller areas than erythromelalgia, for instance the tip of a toe rather than the whole foot)

Raynaud's can precede these other diseases by many years, making it the first presenting symptom. This may be the case in the CREST syndrome, of which Raynaud's is a part.

Patients with secondary Raynaud's can also have symptoms related to their underlying diseases. Raynaud's phenomenon is the initial symptom that presents for 70% of patients with scleroderma, a skin and joint disease.

When Raynaud's phenomenon is limited to one hand or one foot, it is referred to as unilateral Raynaud's. This is an uncommon form, and it is always secondary to local or regional vascular disease. It commonly progresses within several years to affect other limbs as the vascular disease progresses.[14]

Mechanism

Its pathophysiology includes hyperactivation of the sympathetic nervous system causing extreme vasoconstriction of the peripheral blood vessels, leading to tissue hypoxia.

Diagnosis

Distinguishing Raynaud's disease (primary Raynaud's) from Raynaud's phenomenon (secondary Raynaud's) is important. Looking for signs of arthritis or vasculitis, as well as a number of laboratory tests, may separate them. Nail fold capillary examination or "capillaroscopy" is one of the most sensitive methods to diagnose RS with connective tissue disorders, i.e. distinguish a secondary from a primary form objectively.[15]

If suspected to be secondary to systemic sclerosis, one tool which may help aid in the prediction of systemic sclerosis is thermography.[16]

A careful medical history will seek to identify or exclude possible secondary causes.

- Digital artery pressures are measured in the arteries of the fingers before and after the hands have been cooled. A decrease of at least 15 mmHg is diagnostic (positive).

- Doppler ultrasound to assess blood flow

- Full blood count may reveal a normocytic anaemia suggesting the anaemia of chronic disease or kidney failure.

- Blood test for urea and electrolytes may reveal kidney impairment.

- Thyroid function tests may reveal hypothyroidism.

- Tests for rheumatoid factor, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and autoantibody screening may reveal specific causative illnesses or an inflammatory process. Anti-centromere antibodies are common in limited systemic sclerosis (CREST syndrome).

- Nail fold vasculature (capillaroscopy) can be examined under a microscope.

To aid in the diagnosis of Raynaud's phenomenon, multiple sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed.[17][18][19][20] Table 1 below provides a summary of these various diagnostic criteria.[21]

Recently, International Consensus Criteria were developed for the diagnosis of primary Raynaud's phenomenon by a panel of experts in the fields of rheumatology and dermatology.[21]

Management

Secondary Raynaud's is managed primarily by treating the underlying cause, and as primary Raynaud's, avoiding triggers, such as cold, emotional and environmental stress, vibrations and repetitive motions, and avoiding smoking (including passive smoking) and sympathomimetic drugs.[22]

Medications

Medications can be helpful for moderate or severe disease.

- Vasodilators – calcium channel blockers, such as the dihydropyridines nifedipine or amlodipine, preferably slow-release preparations – are often first-line treatment.[22] They have the common side effects of headache, flushing, and ankle edema, but these are not typically of sufficient severity to require cessation of treatment.[23] The limited evidence available shows that calcium-channel blockers are only slightly effective in reducing how often the attacks happen.[24] Although, other studies also reveal that CCBs may be effective at decreasing severity of attacks, pain and disability associated with Raynaud's phenomenon.[25] People whose disease is secondary to erythromelalgia often cannot use vasodilators for therapy, as they trigger 'flares' causing the extremities to become burning red due to too much blood supply.

- People with severe disease prone to ulceration or large artery thrombotic events may be prescribed aspirin.[22]

- Sympatholytic agents, such as the alpha-adrenergic blocker prazosin, may provide temporary relief to secondary Raynaud's phenomenon.[22][26]

- Losartan can, and topical nitrates may, reduce the severity and frequency of attacks, and the phosphodiesterase inhibitors sildenafil and tadalafil may reduce their severity.[22]

- Angiotensin receptor blockers or ACE inhibitors may aid blood flow to the fingers,[22] and some evidence shows that angiotensin receptor blockers (often losartan) reduce frequency and severity of attacks,[27] and possibly better than nifedipine.[28][29]

- The prostaglandin iloprost is used to manage critical ischemia and pulmonary hypertension in Raynaud's phenomenon, and the endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan is used to manage severe pulmonary hypertension and prevent finger ulcers in scleroderma.[22]

- Statins have a protective effect on blood vessels, and SSRIs such as fluoxetine may help symptoms, but the data is weak.[22]

- PDE5 inhibitors are used off-label to treat severe ischemia and ulcers in fingers and toes for people with secondary Raynaud's phenomenon; as of 2016, their role more generally in Raynaud's was not clear.[30]

Surgery

- In severe cases, an endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy procedure can be performed.[31] Here, the nerves that signal the blood vessels of the fingertips to constrict are surgically cut. Microvascular surgery of the affected areas is another possible therapy, but this procedure should be considered as a last resort.

- A more recent treatment for severe Raynaud's is the use of botulinum toxin. The 2009 article[32] studied 19 patients ranging in age from 15 to 72 years with severe Raynaud's phenomenon of which 16 patients (84%) reported pain reduction at rest; 13 patients reported immediate pain relief, three more had gradual pain reduction over 1–2 months. All 13 patients with chronic finger ulcers healed within 60 days. Only 21% of the patients required repeated injections. A 2007 article[33] describes similar improvement in a series of 11 patients. All patients had significant relief of pain.

Alternative medicine

Evidence does not support the use of alternative medicine, including acupuncture and laser therapy.[3]

Prognosis

The prognosis of primary Raynaud syndrome is often very favorable, with no mortality and little morbidity. However, a minority develops gangrene. The prognosis of secondary Raynaud is dependent on the underlying disease, and how effective blood flow-restoring maneuvers are.[34]

References

- "What Is Raynaud's?". NHLBI. 21 March 2014. Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Raynaud's?". NHLBI. 21 March 2014. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Wigley, FM; Flavahan, NA (11 August 2016). "Raynaud's Phenomenon". The New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (6): 556–65. doi:10.1056/nejmra1507638. PMID 27509103.

- "Who Is at Risk for Raynaud's?". NHLBI. 21 March 2014. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Barker, Roger A. (2005). The A-Z of Neurological Practice: A Guide to Clinical Neurology. Cambridge University Press. p. 728. ISBN 9780521629607. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017.

- "What Causes Raynaud's?". NHLBI. 21 March 2014. Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Holmen OL, Backe B (2009). "An underdiagnosed cause of nipple pain presented on a camera phone". BMJ. 339: b2553. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2553. S2CID 71701101.

- Pistorius MA, Planchon B, Schott JJ, Lemarec H (February 2006). "[Heredity and genetic aspects of Raynaud's disease]". Journal des Maladies Vasculaires (in French). 31 (1): 10–5. doi:10.1016/S0398-0499(06)76512-X. PMID 16609626.

- Wigley, Fredrick M.; Flavahan, Nicholas A. (10 August 2016). "Raynaud's Phenomenon". New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (6): 556–565. doi:10.1056/nejmra1507638. PMID 27509103.

- Gayraud M (January 2007). "Raynaud's phenomenon". Joint, Bone, Spine. 74 (1): e1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.07.002. PMID 17218139.

- Goldman W, Seltzer R, Reuman P (2008). "Association between treatment with central nervous system stimulants and Raynaud's syndrome in children: A retrospective case–control study of rheumatology patients". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 58 (2): 563–566. doi:10.1002/art.23301. PMID 18240233.

- "Raynaud's disease Treatments and drugs - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Archived from the original on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- Berlin AL, Pehr K (March 2004). "Coexistence of erythromelalgia and Raynaud's phenomenon". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 50 (3): 456–60. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(03)02121-2. PMID 14988692.

- Priollet P (October 1998). "[Raynaud's phenomena: diagnostic and treatment study]". La Revue du Praticien (in French). 48 (15): 1659–64. PMID 9814067.

- Belch, Jill; Carlizza, Anita; Carpentier, Patrick H.; Constans, Joel; Khan, Faisel; Wautrecht, Jean-Claude; Visona, Adriana; Heiss, Christian; Brodeman, Marianne; Pécsvárady, Zsolt; Roztocil, Karel (12 September 2017). "ESVM guidelines – the diagnosis and management of Raynaud's phenomenon". Vasa. 46 (6): 413–423. doi:10.1024/0301-1526/a000661. ISSN 0301-1526. PMID 28895508.

- Anderson ME, Moore TL, Lunt M, Herrick AL (March 2007). "The 'distal-dorsal difference': a thermographic parameter by which to differentiate between primary and secondary Raynaud's phenomenon". Rheumatology. 46 (3): 533–8. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kel330. PMID 17018538.

- Brennan P, Silman A, Black C (May 1993). "Validity and reliability of three methods used in the diagnosis of Raynaud's phenomenon. The UK Scleroderma Study Group". British Journal of Rheumatology. 32 (5): 357–361. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/32.5.357. PMID 8495253.

- Wigley FM (September 2002). "Clinical Practice.Raynaud's phenomenon". New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (13): 1001–1008. doi:10.1056/nejmcp013013. PMID 12324557.

- LeRoy EC, Medsger TA (September–October 1992). "Raynaud's phenomenon: a proposal for classification". Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 10 (5): 485–488. PMID 1458701.

- Maricq HR, Weinrich MC (March 1998). "Diagnosis of Raynaud's phenomenon assisted by color charts". Journal of Rheumatology. 15 (3): 454–459. PMID 3379622.

- Maverakis E, Patel F, Kronenberg D (2014). "International consensus criteria for the diagnosis of Raynaud's phenomenon". Journal of Autoimmunity. 48–49: 60–5. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.020. PMC 4018202. PMID 24491823.

- Mikuls, Ted R; Canella, Amy C; Moore, Gerald F; Erickson, Alan R; Thiele, Geoffery M; O'Dell, James R (2013). "Connective Tissue Diseases". Rheumatology. London: Manson Publishing. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-84076-173-3.

- Smith CR, Rodeheffer RJ (January 1985). "Raynaud's phenomenon: pathophysiologic features and treatment with calcium-channel blockers". The American Journal of Cardiology. 55 (3): 154B–157B. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(85)90625-3. PMID 3881908.

- Ennis, Holly; Hughes, Michael; Anderson, Marina E.; Wilkinson, Jack; Herrick, Ariane L. (25 February 2016). "Calcium channel blockers for primary Raynaud's phenomenon". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD002069. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002069.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7065590. PMID 26914257.

- Rirash, Fadumo; Tingey, Paul C; Harding, Sarah E; Maxwell, Lara J; Tanjong Ghogomu, Elizabeth; Wells, George A; Tugwell, Peter; Pope, Janet (13 December 2017). "Calcium channel blockers for primary and secondary Raynaud's phenomenon". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD000467. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000467.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6486273. PMID 29237099.

- Harding, Sarah E; Tingey, Paul C; Pope, Janet; Fenlon, D; Furst, Dan; Shea, Beverley; Silman, Alan; Thompson, A; Wells, George A (27 April 1998). "Prazosin for Raynaud's phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD000956. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000956. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 7032637. PMID 10796398.

- Pancera P, Sansone S, Secchi S, Covi G, Lechi A (November 1997). "The effects of thromboxane A2 inhibition (picotamide) and angiotensin II receptor blockade (losartan) in primary Raynaud's phenomenon". Journal of Internal Medicine. 242 (5): 373–6. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00219.x. PMID 9408065. S2CID 2052430.

- Dziadzio M, Denton CP, Smith R, et al. (December 1999). "Losartan therapy for Raynaud's phenomenon and scleroderma: clinical and biochemical findings in a fifteen-week, randomized, parallel-group, controlled trial". Arthritis and Rheumatism. Elsevier Saunergic blockers such as prazosin can be used to control Raynaud's vasospasms under supervision of a health care provider. 42 (12): 2646–55. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199912)42:12<2646::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 10616013.

- Waldo R (March 1979). "Prazosin relieves Raynaud's vasospasm". JAMA. 241 (10): 1037. doi:10.1001/jama.241.10.1037. PMID 762741.

- Linnemann B, Erbe M (2016). "Raynaud's phenomenon and digital ischaemia – pharmacologic approach and alternative treatment options". VASA. 45 (3): 201–12. doi:10.1024/0301-1526/a000526. PMID 27129065.

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors (e.g., sildenafil) can also improve [Raynaud's phenomenon] symptoms and ulcer healing

- Wang WH, Lai CS, Chang KP, et al. (October 2006). "Peripheral sympathectomy for Raynaud's phenomenon: a salvage procedure". The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences. 22 (10): 491–9. doi:10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70343-2. PMID 17098681.

- Neumeister MW, Chambers CB, Herron MS, et al. (July 2009). "Botox therapy for ischemic digits". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 124 (1): 191–201. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a80576. PMID 19568080. S2CID 26698472.

- Van Beek AL, Lim PK, Gear AJ, Pritzker MR (January 2007). "Management of vasospastic disorders with botulinum toxin A". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 119 (1): 217–26. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000244860.00674.57. PMID 17255677. S2CID 8696332.

- "Raynaud Phenomenon: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Etiology". 6 December 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

- What Is Raynaud's Disease at National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- Questions and Answers about Raynaud's Phenomenon at National Institutes of Health

- Bakst R, Merola JF, Franks AG, Sanchez M (October 2008). "Raynaud's phenomenon: pathogenesis and management". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 59 (4): 633–53. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.004. PMID 18656283.