Bashar al-Assad

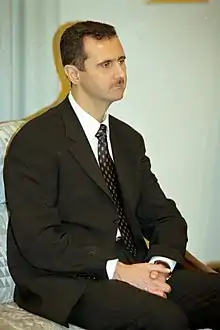

Bashar Hafez al-Assad[lower-alpha 1] (Arabic: بَشَّارُ ٱلْأَسَدِ, born 11 September 1965) is a Syrian politician who is the 19th president of Syria, since 17 July 2000. In addition, he is the commander-in-chief of the Syrian Armed Forces and the Secretary-General of the Central Command of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party.

Marshal Bashar al-Assad | |

|---|---|

بَشَّارُ ٱلْأَسَدِ | |

.jpeg.webp) Assad in 2022 | |

| 19th President of Syria | |

Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 17 July 2000 | |

| Prime Minister | Muhammad Mustafa Mero Muhammad Naji al-Otari Adel Safar Riyad Farid Hijab Omar Ibrahim Ghalawanji Wael Nader al-Halqi Imad Khamis Hussein Arnous |

| Vice President | Abdul Halim Khaddam Zuhair Masharqa Farouk al-Sharaa Najah al-Attar |

| Preceded by | Hafez al-Assad Abdul Halim Khaddam (Acting) |

| Secretary-General of the Central Command of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party | |

Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 24 June 2000 | |

| Deputy | Sulayman Qaddah Mohammed Saeed Bekheitan Hilal Hilal |

| Preceded by | Hafez al-Assad |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Bashar Hafez al-Assad 11 September 1965 Damascus, Damascus Governorate, Syria |

| Political party | Syrian Ba'ath Party |

| Other political affiliations | National Progressive Front |

| Spouse | Asma Akhras (m. 2000) |

| Relations | al-Assad family |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Damascus University (BSc), (MSc)[2] |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Syrian Armed Forces |

| Years of service | 1988–present |

| Rank | |

| Unit | Republican Guard (until 2000) |

| Commands | Syrian Armed Forces |

| Battles/wars | Syrian civil war |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

His father, Hafez al-Assad, was the president of Syria before him, serving from 1971 to 2000. Born and raised in Damascus, Bashar al-Assad graduated from the medical school of Damascus University in 1988 and began to work as a doctor in the Syrian Army. Four years later, he attended postgraduate studies at the Western Eye Hospital in London, specialising in ophthalmology. In 1994, after his elder brother Bassel died in a car accident, Bashar was recalled to Syria to take over Bassel's role as heir apparent. He entered the military academy, taking charge of the Syrian military presence in Lebanon in 1998.

Political scientists have characterised the Assad family's rule of Syria as a personalist dictatorship.[lower-alpha 2] On 17 July 2000, Assad became president, succeeding his father, who died in office on 10 June 2000. In the 2000 and 2007 elections, he received 97.29% and 97.6% support, respectively.[lower-alpha 3] On 16 July 2014, Assad was sworn in for another seven-year term after another election gave him 88.7% of the vote.[lower-alpha 4] The election was held only in areas controlled by the Syrian government during the country's ongoing civil war and was criticised by the United Nations (UN).[21][22] Assad was re-elected in 2021 with over 95% of the vote in national election. Throughout his leadership, human rights groups have characterized Syria's human rights situation as poor. The Assad government describes itself as secular,[23] while some political scientists write that his regime exploits sectarian tensions in the country.[24][25]

Once seen by many states as a potential reformer, the United States (U.S.), the European Union (EU), and the majority of the Arab League called for Assad's resignation from the presidency in 2011 after he ordered a violent crackdown on Arab Spring protesters, which led to the Syrian civil war.[26][27] In December 2013, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay stated that findings from an inquiry by the UN implicated Assad in war crimes.[28] The OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism concluded in October 2017 that Assad's government was responsible for the Khan Shaykhun chemical attack.[29] In June 2014, the American Syrian Accountability Project included Assad on a list of war crimes indictments of government officials and rebels it sent to the International Criminal Court.[30] Assad has rejected allegations of war crimes and criticised the American-led intervention in Syria for attempting regime change.[31][32]

Early life, family and education

Bashar Hafez al-Assad was born in Damascus on 11 September 1965, the second son and third child of Anisa Makhlouf and Hafez al-Assad.[33] Al-Assad in Arabic means "the Lion". Assad's paternal grandfather, Ali Sulayman al-Assad, had managed to change his status from peasant to minor notable and, to reflect this, in 1927 he had changed the family name from Wahsh (meaning "Savage") to Al-Assad.[34]

Assad's father, Hafez, was born to an impoverished rural family of Alawite background and rose through the Ba'ath Party ranks to take control of the Syrian branch of the Party in the 1970 Corrective Revolution, culminating in his rise to the Syrian presidency.[35] Hafez promoted his supporters within the Ba'ath Party, many of whom were also of Alawite background.[33][36] After the revolution, Alawite strongmen were installed while Sunnis, Druze, and Ismailis were removed from the army and Ba'ath party.[37]

The younger Assad had five siblings, three of whom are deceased. A sister named Bushra died in infancy.[38] Assad's youngest brother, Majd, was not a public figure and little is known about him other than he was intellectually disabled,[39] and died in 2009 after a "long illness".[40]

Unlike his brothers Bassel and Maher, and second sister, also named Bushra, Bashar was quiet, reserved and lacked interest in politics or the military.[41][39][42] The Assad children reportedly rarely saw their father,[43] and Bashar later stated that he only entered his father's office once while he was president.[44] He was described as "soft-spoken",[45] and according to a university friend, he was timid, avoided eye contact and spoke in a low voice.[46]

Assad received his primary and secondary education in the Arab-French al-Hurriya School in Damascus.[41] In 1982, he graduated from high school and then studied medicine at Damascus University.[47]

Medical career and rise to power

In 1988, Assad graduated from medical school and began working as an army doctor at the Tishrin Military Hospital on the outskirts of Damascus.[48][49] Four years later, he settled in London to start postgraduate training in ophthalmology at the Western Eye Hospital.[2] He was described as a "geeky I.T. guy" during his time in London.[50] Bashar had few political aspirations,[51] and his father had been grooming Bashar's older brother Bassel as the future president.[52] However, he died in a car accident in 1994 and Bashar was recalled to the Syrian Army shortly thereafter.[53]

Soon after the death of Bassel, Hafez al-Assad decided to make Bashar the new heir apparent.[54] Over the next six and a half years, until his death in 2000, Hafez prepared Bashar for taking over power. General Bahjat Suleiman, an officer in the Defense Companies, was entrusted with overseeing preparations for a smooth transition,[55][43] which were made on three levels. First, support was built up for Bashar in the military and security apparatus. Second, Bashar's image was established with the public. And lastly, Bashar was familiarised with the mechanisms of running the country.[56]

To establish his credentials in the military, Bashar entered the military academy at Homs in 1994 and was propelled through the ranks to become a colonel of the elite Syrian Republican Guard in January 1999.[48][57][58] To establish a power base for Bashar in the military, old divisional commanders were pushed into retirement, and new, young, Alawite officers with loyalties to him took their place.[59]

In 1998, Bashar took charge of Syria's Lebanon file, which had since the 1970s been handled by Vice President Abdul Halim Khaddam, who had until then been a potential contender for president.[59] By taking charge of Syrian affairs in Lebanon, Bashar was able to push Khaddam aside and establish his own power base in Lebanon.[60] In the same year, after minor consultation with Lebanese politicians, Bashar installed Emile Lahoud, a loyal ally of his, as the President of Lebanon and pushed former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri aside, by not placing his political weight behind his nomination as prime minister.[61] To further weaken the old Syrian order in Lebanon, Bashar replaced the long-serving de facto Syrian High Commissioner of Lebanon, Ghazi Kanaan, with Rustum Ghazaleh.[62]

Parallel to his military career, Bashar was engaged in public affairs. He was granted wide powers and became head of the bureau to receive complaints and appeals of citizens, and led a campaign against corruption. As a result of this campaign, many of Bashar's potential rivals for president were put on trial for corruption.[48] Bashar also became the President of the Syrian Computer Society and helped to introduce the internet in Syria, which aided his image as a moderniser and reformer.[63]

Presidency

Damascus Spring and before civil war: 2000–2011

Politics of Syria |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

After the death of Hafez al-Assad on 10 June 2000, the Constitution of Syria was amended. The minimum age requirement for the presidency was lowered from 40 to 34, which was Bashar's age at the time.[64] Assad was then confirmed president on 10 July 2000, with 97.29% support for his leadership.[9][10][11] In line with his role as President of Syria, he was also appointed the commander-in-chief of the Syrian Armed Forces and Regional Secretary of the Ba'ath Party.[63]

Immediately after he took office, a reform movement made cautious advances during the Damascus Spring, which led to the shut down of Mezzeh prison and the declaration of a wide-ranging amnesty releasing hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood affiliated political prisoners.[65] However, security crackdowns commenced again within the year.[66][67] Many analysts stated that reform under Assad had been inhibited by the "old guard", members of the government loyal to his late father.[63]

During the war on terror, Assad allied his country with the West. Syria was a major site of extraordinary rendition by the CIA of al-Qaeda suspects, who were interrogated in Syrian prisons.[68][69][70]

Soon after Assad assumed power, he "made Syria's link with Hezbollah—and its patrons in Tehran—the central component of his security doctrine",[71] and in his foreign policy, Assad is an outspoken critic of the U.S., Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey.[72]

In 2005, Rafic Hariri, the former prime minister of Lebanon, was assassinated. The Christian Science Monitor reported that "Syria was widely blamed for Hariri's murder. In the months leading to the assassination, relations between Hariri and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad plummeted amid an atmosphere of threats and intimidation."[73] The BBC reported in December 2005 that an interim UN report "implicated Syrian officials", while "Damascus has strongly denied involvement in the car bomb which killed Hariri in February".[74]

On 27 May 2007, Assad was approved for another seven-year term in a referendum on his presidency, with 97.6% of the votes supporting his continued leadership.[75] Opposition parties were not allowed in the country and Assad was the only candidate in the referendum.[11]

2011–2015

Mass protests in Syria began on 26 January 2011. Protesters called for political reforms and the reinstatement of civil rights, as well as an end to the state of emergency which had been in place since 1963.[76] One attempt at a "day of rage" was set for 4–5 February, though it ended uneventfully.[77] Protests on 18–19 March were the largest to take place in Syria for decades, and the Syrian authority responded with violence against its protesting citizens.[78]

The U.S. imposed limited sanctions against the Assad government in April 2011, followed by Barack Obama's executive order as of 18 May 2011 targeting Bashar Assad specifically and six other senior officials.[79][80][81] On 23 May 2011, the EU foreign ministers agreed at a meeting in Brussels to add Assad and nine other officials to a list affected by travel bans and asset freezes.[82] On 24 May 2011, Canada imposed sanctions on Syrian leaders, including Assad.[83]

On 20 June, in response to the demands of protesters and foreign pressure, Assad promised a national dialogue involving movement toward reform, new parliamentary elections, and greater freedoms. He also urged refugees to return home from Turkey, while assuring them amnesty and blaming all unrest on a small number of saboteurs.[84] Assad blamed the unrest on "conspiracies" and accused the Syrian opposition and protestors of "fitna", breaking with the Syrian Ba'ath Party's strict tradition of secularism.[85]

In July 2011, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said Assad had "lost legitimacy" as president.[80] On 18 August 2011, Barack Obama issued a written statement that urged Assad to "step aside".[86][87][88]

In August, the cartoonist Ali Farzat, a critic of Assad's government, was attacked. Relatives of the humourist told media outlets that the attackers threatened to break Farzat's bones as a warning for him to stop drawing cartoons of government officials, particularly Assad. Farzat was hospitalised with fractures in both hands and blunt force trauma to the head.[89][90]

Since October 2011, Russia, as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, repeatedly vetoed Western-sponsored draft resolutions in the UN Security Council that would have left open the possibility of UN sanctions, or even military intervention, against the Assad government.[91][92][93]

By the end of January 2012, it was reported by Reuters that over 5,000 civilians and protesters (including armed militants) had been killed by the Syrian army, security agents and militia (Shabiha), while 1,100 people had been killed by "terrorist armed forces".[94]

On 10 January 2012, Assad gave a speech in which he maintained the uprising was engineered by foreign countries and proclaimed that "victory [was] near". He also said that the Arab League, by suspending Syria, revealed that it was no longer Arab. However, Assad also said the country would not "close doors" to an Arab-brokered solution if "national sovereignty" was respected. He also said a referendum on a new constitution could be held in March.[95]

On 27 February 2012, Syria claimed that a proposal that a new constitution be drafted received 90% support during the relevant referendum. The referendum introduced a fourteen-year cumulative term limit for the president of Syria. The referendum was pronounced meaningless by foreign nations including the U.S. and Turkey; the EU announced fresh sanctions against key regime figures.[96] In July 2012, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov denounced Western powers for what he said amounted to blackmail thus provoking a civil war in Syria.[97]

On 15 July 2012, the International Committee of the Red Cross declared Syria to be in a state of civil war,[98] as the nationwide death toll for all sides was reported to have neared 20,000.[99]

On 6 January 2013, Assad, in his first major speech since June, said that the conflict in his country was due to "enemies" outside of Syria who would "go to Hell" and that they would "be taught a lesson". However, he said that he was still open to a political solution saying that failed attempts at a solution "does not mean we are not interested in a political solution."[100][101]

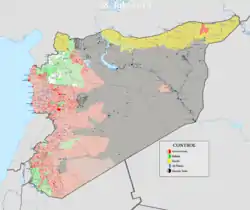

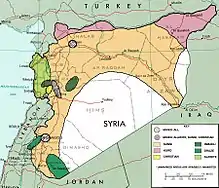

After the fall of four military bases in September 2014,[102] which were the last government footholds in the Raqqa Governorate, Assad received significant criticism from his Alawite base of support.[103] This included remarks made by Douraid al-Assad, cousin of Bashar al-Assad, demanding the resignation of the Syrian Defence Minister, Fahd Jassem al-Freij, following the massacre by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) of hundreds of government troops captured after the ISIL victory at Tabqa Airbase.[104] This was shortly followed by Alawite protests in Homs demanding the resignation of the governor,[105] and the dismissal of Assad's cousin Hafez Makhlouf from his security position leading to his subsequent exile to Belarus.[106] Growing resentment towards Assad among Alawites was fuelled by the disproportionate number of soldiers killed in fighting hailing from Alawite areas,[107] a sense that the Assad regime has abandoned them,[108] as well as the failing economic situation.[109] Figures close to Assad began voicing concerns regarding the likelihood of its survival, with one saying in late 2014; "I don't see the current situation as sustainable ... I think Damascus will collapse at some point."[102]

In 2015, several members of the Assad family died in Latakia under unclear circumstances.[110] On 14 March, an influential cousin of Assad and founder of the shabiha, Mohammed Toufic al-Assad, was assassinated with five bullets to the head in a dispute over influence in Qardaha—the ancestral home of the Assad family.[111] In April 2015, Assad ordered the arrest of his cousin Munther al-Assad in Alzirah, Latakia.[112] It remains unclear whether the arrest was due to actual crimes.[113]

After a string of government defeats in northern and southern Syria, analysts noted growing government instability coupled with continued waning support for the Assad government among its core Alawite base of support,[114] and that there were increasing reports of Assad relatives, Alawites, and businessmen fleeing Damascus for Latakia and foreign countries.[115][116] Intelligence chief Ali Mamlouk was placed under house arrest sometime in April and stood accused of plotting with Assad's exiled uncle Rifaat al-Assad to replace Bashar as president.[117] Further high-profile deaths included the commanders of the Fourth Armoured Division, the Belli military airbase, the army's special forces and of the First Armoured Division, with an errant air strike during the Palmyra offensive killing two officers who were reportedly related to Assad.[118]

Since Russian intervention 2015–present

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

On 4 September 2015, Russian President Vladimir Putin said that Russia was providing the Assad government with sufficiently "serious" help: with both logistical and military support.[119][120] Shortly after the start of direct military intervention by Russia on 30 September 2015 at the formal request of the Syrian government, Putin stated the military operation had been thoroughly prepared in advance and defined Russia's goal in Syria as "stabilising the legitimate power in Syria and creating the conditions for political compromise".[121]

In November 2015, Assad reiterated that a diplomatic process to bring the country's civil war to an end could not begin while it was occupied by "terrorists", although it was considered by BBC News to be unclear whether he meant only ISIL or Western-supported rebels as well.[122] On 22 November, Assad said that within two months of its air campaign Russia had achieved more in its fight against ISIL than the U.S.-led coalition had achieved in a year.[123] In an interview with Česká televize on 1 December, he said that the leaders who demanded his resignation were of no interest to him, as nobody takes them seriously because they are "shallow" and controlled by the U.S.[124][125] At the end of December 2015, senior U.S. officials privately admitted that Russia had achieved its central goal of stabilising Syria and, with the expenses relatively low, could sustain the operation at this level for years to come.[126]

In January 2016, Putin stated that Russia was supporting Assad's forces and was ready to back anti-Assad rebels as long as they were fighting ISIL.

On 22 January 2016, the Financial Times, citing anonymous "senior western intelligence officials", claimed that Russian general Igor Sergun, the director of GRU, the Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, had shortly before his sudden death on 3 January 2016 been sent to Damascus with a message from Vladimir Putin asking that President Assad step aside.[127] The Financial Times' report was denied by Putin's spokesman.[128]

It was reported in December 2016 that Assad's forces had retaken half of rebel-held Aleppo, ending a 6-year stalemate in the city.[129][130] On 15 December, as it was reported government forces were on the brink of retaking all of Aleppo—a "turning point" in the civil war, Assad celebrated the "liberation" of the city, and stated, "History is being written by every Syrian citizen."[131]

After the election of Donald Trump, the priority of the U.S. concerning Assad was unlike the priority of the Obama administration, and in March 2017 U.S. Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley stated the U.S. was no longer focused on "getting Assad out",[132] but this position changed in the wake of the 2017 Khan Shaykhun chemical attack.[133] Following the missile strikes on a Syrian airbase on the orders of President Trump, Assad's spokesperson described the U.S.' behaviour as "unjust and arrogant aggression" and stated that the missile strikes "do not change the deep policies" of the Syrian government.[134] President Assad also told the Agence France-Presse that Syria's military had given up all its chemical weapons in 2013, and would not have used them if they still retained any, and stated that the chemical attack was a "100 percent fabrication" used to justify a U.S. airstrike.[135] In June 2017, Russian President Putin said "Assad didn't use the [chemical weapons]" and that the chemical attack was "done by people who wanted to blame him for that."[136] UN and international chemical weapons inspectors from the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) found the attack was the work of the Assad regime.[29]

On 7 November 2017, the Syrian government announced that it had signed the Paris Climate Agreement.[137]

On 30 August 2020, the First Hussein Arnous government was formed, which included a new Council of Ministers.[138]

On 10 August 2021, the Second Hussein Arnous government was formed.[139]

Economy

According to ABC News, as a result of the Syrian civil war, "government-controlled Syria is truncated in size, battered and impoverished."[140] Economic sanctions (the Syria Accountability Act) were applied long before the Syrian civil war by the U.S. and were joined by the EU at the outbreak of the civil war, causing disintegration of the Syrian economy.[141] These sanctions were reinforced in October 2014 by the EU and U.S.[142][143] Industry in parts of the country that are still held by the government is heavily state-controlled, with economic liberalisation being reversed during the current conflict.[144] The London School of Economics has stated that as a result of the Syrian civil war, a war economy has developed in Syria.[145] A 2014 European Council on Foreign Relations report also stated that a war economy has formed:

Three years into a conflict that is estimated to have killed at least 140,000 people from both sides, much of the Syrian economy lies in ruins. As the violence has expanded and sanctions have been imposed, assets and infrastructure have been destroyed, economic output has fallen, and investors have fled the country. Unemployment now exceeds 50 percent and half of the population lives below the poverty line ... against this backdrop, a war economy is emerging that is creating significant new economic networks and business activities that feed off the violence, chaos, and lawlessness gripping the country. This war economy – to which Western sanctions have inadvertently contributed – is creating incentives for some Syrians to prolong the conflict and making it harder to end it.[146]

A UN commissioned report by the Syrian Centre for Policy Research states that two-thirds of the Syrian population now lives in "extreme poverty".[147] Unemployment stands at 50 percent.[148] In October 2014, a $50 million mall opened in Tartus which provoked criticism from government supporters and was seen as part of an Assad government policy of attempting to project a sense of normalcy throughout the civil war.[149] A government policy to give preference to families of slain soldiers for government jobs was cancelled after it caused an uproar[107] while rising accusations of corruption caused protests.[109] In December 2014, the EU banned sales of jet fuel to the Assad government, forcing the government to buy more expensive uninsured jet fuel shipments in the future.[150]

Human rights

A 2007 law required internet cafés to record all the comments users post on chat forums.[151] Websites such as Arabic Wikipedia, YouTube, and Facebook were blocked intermittently between 2008 and February 2011.[152][153][154]

Human Rights groups, such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have detailed how the Assad government's secret police allegedly tortured, imprisoned, and killed political opponents, and those who speak out against the government.[155][156] In addition, some 600 Lebanese political prisoners are thought to be held in government prisons since the Syrian occupation of Lebanon, with some held for as long as over 30 years.[157] Since 2006, the Assad government has expanded the use of travel bans against political dissidents.[158] In an interview with ABC News in 2007, Assad stated: "We don't have such [things as] political prisoners," though The New York Times reported the arrest of 30 Syrian political dissidents who were organising a joint opposition front in December 2007, with 3 members of this group considered to be opposition leaders being remanded in custody.[159]

In 2010, Syria banned face veils at universities.[160][161] Following the Syrian uprising in 2011, Assad partially relaxed the veil ban.[162]

Foreign Policy magazine released an editorial on Assad's position in the wake of the 2011 protests:[163]

During its decades of rule... the Assad family developed a strong political safety net by firmly integrating the military into the government. In 1970, Hafez al-Assad, Bashar's father, seized power after rising through the ranks of the Syrian armed forces, during which time he established a network of loyal Alawites by installing them in key posts. In fact, the military, ruling elite, and ruthless secret police are so intertwined that it is now impossible to separate the Assad government from the security establishment.... So... the government and its loyal forces have been able to deter all but the most resolute and fearless oppositional activists. In this respect, the situation in Syria is to a certain degree comparable to Saddam Hussein's strong Sunni minority rule in Iraq.

War crimes

The Federal Bureau of Investigation has stated that at least 10 European citizens were tortured by the Assad government while detained during the Syrian civil war, potentially leaving Assad open to prosecution by individual European countries for war crimes.[164] Stephen Rapp, the U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues, has argued that the crimes allegedly committed by Assad are the worst seen since those of Nazi Germany.[165] In March 2015, Rapp further stated that the case against Assad is "much better" than those against Slobodan Milošević of Serbia or Charles Taylor of Liberia, both of whom were indicted by international tribunals.[166]

In a February 2015 interview with the BBC, Assad described accusations that the Syrian Arab Air Force used barrel bombs as "childish", stating that his forces have never used these types of "barrel" bombs and responded with a joke about not using "cooking pots" either.[167] The BBC Middle East editor conducting the interview, Jeremy Bowen, later described Assad's statement regarding barrel bombs as "patently not true".[168][169]

Nadim Shehadi, the director of The Fares Center for Eastern Mediterranean Studies, stated that "In the early 1990s, Saddam Hussein was massacring his people and we were worried about the weapons inspectors," and claimed that "Assad did that too. He kept us busy with chemical weapons when he massacred his people."[170][171]

In September 2015, France began an inquiry into Assad for crimes against humanity, with French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius stating "Faced with these crimes that offend the human conscience, this bureaucracy of horror, faced with this denial of the values of humanity, it is our responsibility to act against the impunity of the killers".[172]

In February 2016, head of the UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria, Paulo Pinheiro, told reporters: "The mass scale of deaths of detainees suggests that the government of Syria is responsible for acts that amount to extermination as a crime against humanity." The UN Commission reported finding "unimaginable abuses", including women and children as young as seven perishing while being held by Syrian authorities. The report also stated: "There are reasonable grounds to believe that high-ranking officers—including the heads of branches and directorates—commanding these detention facilities, those in charge of the military police, as well as their civilian superiors, knew of the vast number of deaths occurring in detention facilities ... yet did not take action to prevent abuse, investigate allegations or prosecute those responsible".[173]

In March 2016, the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs led by New Jersey Rep. Chris Smith called on the Obama administration to create a war crimes tribunal to investigate and prosecute violations "whether committed by the officials of the Government of Syria or other parties to the civil war".[174]

In April 2017, there was a sarin chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun that killed more than 80 people. The attack prompted U.S. President Donald Trump to order the U.S. military to launch 59 missiles at a Syrian airbase.[175] Several months later, a joint report from the UN and international chemical weapons inspectors found the attack was the work of the Assad regime.[29]

In April 2018, an alleged chemical attack occurred in Douma, prompting the U.S. and its and allies to accuse Assad of violating international laws and initiating the 2018 bombing of Damascus and Homs. Both Syria and Russia denied the involvement of the Syrian government at this time.[176][177]

In June 2018, Germany's chief prosecutor issued an international arrest warrant for one of Assad's most senior military officials, Jamil Hassan.[178] Hassan is the head of Syria's powerful Air Force Intelligence Directorate. Detention centers run by Air Force Intelligence are among the most notorious in Syria, and thousands are believed to have died because of torture or neglect. Charges filed against Hassan claim he had command responsibility over the facilities and therefore knew of the abuse. The move against Hassan marked an important milestone of prosecutors trying to bring senior members of Assad's inner circle to trial for war crimes.

In an investigative report about the Tadamon Massacre, Professors Uğur Ümit Üngör and Annsar Shahhoud, found witnesses who attested that Assad gave orders for the Syrian Military Intelligence to direct the Shabiha to kill civilians, in what is the first known association between the regime and the militia.[179]

Foreign policies

Iraq

Assad opposed the 2003 invasion of Iraq despite a long-standing animosity between the Syrian and Iraqi governments. Assad used Syria's seat in one of the rotating positions on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to try to prevent the invasion of Iraq.[180]

According to veteran U.S. intelligence officer Malcolm Nance, the Syrian government had developed deep relations with former Vice Chairman of the Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri. Despite the historical differences between the two Ba'ath factions, al-Douri reportedly urged Saddam to open oil pipelines with Syria, building a financial relationship with the Assad family. After the 2003 Invasion of Iraq, al-Douri allegedly fled to Damascus where he organised the National Command of the Islamic Resistance which co-ordinated major combat operations during the Iraqi insurgency.[181][182] In 2009, General David Petraeus, who was at the time heading the U.S. Central Command, told reporters from Al Arabiya that al-Douri was residing in Syria.[183]

The U.S. commander of the coalition forces in Iraq, George W. Casey Jr., accused Assad of providing funding, logistics, and training to insurgents in Iraq to launch attacks against U.S. and allied forces occupying Iraq.[184] Iraqi leaders such as former national security advisor Mowaffak al-Rubaie and former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki have accused Assad of harbouring and supporting Iraqi militants.[185][186]

Egypt

At the outset of the Arab Spring, Syrian state media focused primarily upon Hosni Mubarak of Egypt, demonising him as pro-U.S. and comparing him unfavourably with Assad.[187] Assad told The Wall Street Journal in this same period that he considered himself "anti-Israel" and "anti-West", and that because of these policies he was not in danger of being overthrown.[72]

Following the election of Muslim Brotherhood politician Mohamed Morsi as the next Egyptian president, relations became extremely strained. The Muslim Brotherhood is a banned organisation and its membership is a capital offence in Syria. Egypt severed all relations with Syria in June 2013. Diplomatic relations were restored and the embassies were reopened after the Morsi government was deposed weeks later by General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. In July 2013, the two countries agreed to reopen the Egyptian consulate in Damascus and the Syrian consulate in Cairo.[188]

In late-November 2016, some Arab media outlets reported Egyptian pilots arrived in mid-November to Syria to help the Syrian government in its fight against the Islamic State and Al Nusra front.[189] This came after Sisi publicly stated he supports the Syrian military in the civil war in Syria.[190] However, several days later, Egypt officially denied it has a military presence in Syria.[191]

Although Egypt has not been vocal in support for any sides of Syria's ongoing civil war, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi said in 2016 that his nation's priority is "supporting national armies", which he said included the Syrian Armed Forces.[192] He also said regarding Egypt's stance in the conflict: "Our stance in Egypt is to respect the will of the Syrian people, and that a political solution to the Syrian crisis is the most suitable way, and to seriously deal with terrorist groups and disarm them".[192] Egypt's support for a political solution was reaffirmed in February 2017. Egypt's Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Ahmed Abu Zeid, said that Egyptian foreign minister Sameh Shoukry, "during his meeting with UN Special Envoy to Syria, Staffan de Mistura, on Saturday confirmed Egypt's rejection of any military intervention that would violate Syrian sovereignty and undermine opportunities of the standing political solutions."[193]

Egypt has also expressed great interest in rebuilding postwar Syria, with many Egyptian companies and businessmen discussing investment opportunities in Syria as well as participation in the reconstruction effort. Tarik al-Nabrawi, president of Egypt's Engineers Syndicate said that 2018 will witness a "boom and influential role for Egyptian construction companies in Syria and to open the door for other companies — in the electricity, building material, steel, aluminum, ceramics and sanitary material fields among others — to work in the Syrian market and participate in rebuilding cities and facilities that the war has destroyed."[194] On 25 February 2018, Syrian state news reported that an Egyptian delegation composed of "members of the Islamic and Arab Assembly for supporting Resistance and Future Pioneers movement as well as a number of figures", including Jamal Zahran and Farouk Hassan, visited the Syrian consulate in Cairo to express solidarity with the Syrian government.[195]

Lebanon

On 5 March 2005, Assad announced that Syrian forces would begin its withdrawal from Lebanon in his address to the Syrian parliament.[196] Syria completed its full withdrawal from Lebanon on 30 April 2005.[197] Assad argued that Syria's gradual withdrawal of troops from Lebanon was a result of the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri.[198] According to testimony submitted to the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, when talking to Rafic Hariri at the Presidential Palace in Damascus in August 2004, Assad allegedly said to him, "I will break Lebanon over your [Hariri's] head and over Walid Jumblatt's head" if Émile Lahoud was not allowed to remain in office despite Hariri's objections; that incident was thought to be linked to Hariri's subsequent assassination.[199] In early 2015, journalist and ad hoc Lebanese-Syrian intermediary Ali Hamade stated before the Special Tribunal for Lebanon that Rafic Hariri's attempts to reduce tensions with Syria were considered a "mockery" by Assad.[200]

Assad's position was considered by some to have been weakened by the withdrawal of Syrian troops from Lebanon following the Cedar Revolution in 2005. There has also been pressure from the U.S. concerning claims that Syria is linked to terrorist networks, exacerbated by Syrian condemnation of the assassination of Hezbollah military leader, Imad Mughniyah, in Damascus in 2008. Interior Minister Bassam Abdul-Majeed stated that "Syria, which condemns this cowardly terrorist act, expresses condolences to the martyr family and to the Lebanese people."[201]

In May 2015, Lebanese politician Michel Samaha was sentenced to four-and-a-half years in jail for his role in a terrorist bomb plot that he claimed Assad was aware of.[202]

Arab–Israeli conflict

The U.S., the EU, the March 14 Alliance, and France accuse Assad of providing support to militant groups active against Israel and opposition political groups. The latter category would include most political parties other than Hezbollah, Hamas, and the Islamic Jihad Movement in Palestine.[203]

In a speech about the 2006 Lebanon War in August 2006, Assad said that Hezbollah had "hoisted the banner of victory", hailing its actions as a "successful resistance."[204]

In April 2008, Assad told a Qatari newspaper that Syria and Israel had been discussing a peace treaty for a year. This was confirmed in May 2008, by a spokesman for Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert. As well as the treaty, the future of the Golan Heights was being discussed. Assad was quoted in The Guardian as telling the Qatari paper:

... there would be no direct negotiations with Israel until a new U.S. president takes office. The U.S. was the only party qualified to sponsor any direct talks, [Assad] told the paper, but added that the Bush administration "does not have the vision or will for the peace process. It does not have anything."[205]

According to leaked American cables, Assad called Hamas an "uninvited guest" and said "If you want me to be effective and active, I have to have a relationship with all parties. Hamas is Muslim Brotherhood, but we have to deal with the reality of their presence," comparing Hamas to the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood which was crushed by his father, Hafez al-Assad. He also said Hamas would disappear if peace was brought to the Middle East.[206][207]

Assad has indicated that the peace treaty that he envisions would not be the same kind of peace treaty Israel has with Egypt, where there is a legal border crossing and open trade. In a 2006 interview with Charlie Rose, Assad said: "There is a big difference between talking about a peace treaty and peace. A peace treaty is like a permanent ceasefire. There's no war, maybe you have an embassy, but you actually won't have trade, you won't have normal relations because people will not be sympathetic to this relation as long as they are sympathetic with the Palestinians: half a million who live in Syria and half a million in Lebanon and another few millions in other Arab countries."[198]

During the visit of Pope John Paul II to Syria in 2001, Assad requested an apology to Muslims for the Crusades and criticised Israeli treatment of Palestinians, stating that "territories in Lebanon, the Golan and Palestine have been occupied by those who killed the principle of equality when they claimed that God created a people distinguished above all other peoples".[208] He also compared the suffering of Palestinians at the hands of the Israelis to the suffering endured by Jesus in Judea, and said that "they tried to kill the principles of all religions with the same mentality in which they betrayed Jesus Christ and the same way they tried to betray and kill the Prophet Muhammad".[209][210][211][212] Responding to accusations that his comment was antisemitic, Assad said that "We in Syria reject the term antisemitism. ... Semites are a race and [Syrians] not only belong to this race, but are its core. Judaism, on the other hand, is a religion which can be attributed to all races."[213] He also stated that "I was talking about Israelis, not Jews. ... When I say Israel carries out killings, it's the reality: Israel tortures Palestinians. I didn't speak about Jews," and criticised Western media outlets for misinterpreting his comments.[214]

In February 2011, Assad backed an initiative to restore ten synagogues in Syria, which had a Jewish community numbering 30,000 in 1947, but only 200 Jews by 2011.[215]

United States

Assad met with U.S. scientists and policy leaders during a science diplomacy visit in 2009, and he expressed interest in building research universities and using science and technology to promote innovation and economic growth.[216]

In response to Executive Order 13769 which mandated refugees from Syria be indefinitely suspended from being able to resettle in the U.S., Assad appeared to defend the measure, stating "It's against the terrorists that would infiltrate some of the immigrants to the West... I think the aim of Trump is to prevent those people from coming," adding that it was "not against the Syrian people".[217] This reaction was in contrast to other leaders of countries affected by the Executive Order who condemned it.[218]

North Korea

North Korea is alleged to have aided Syria in developing and enhancing a ballistic missiles programme.[219][220] They also reportedly helped Syria develop a suspected nuclear reactor in the Deir ez-Zor Governorate. U.S. officials claimed the reactor was probably "not intended for peaceful purposes", but American senior intelligence officials doubted it was meant for the production of nuclear weapons.[221] The supposed nuclear reactor was destroyed by the Israeli Air Force in 2007 during Operation Orchard.[222] Following the airstrike, Syria wrote a letter to Secretary-General of the UN Ban Ki-moon calling the incursion a "breach of airspace of the Syrian Arab Republic" and "not the first time Israel has violated" Syrian airspace.[223]

While hosting an 8 March 2015 delegation from North Korea led by North Korean Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Sin Hong Chol, Assad stated that Syria and North Korea were being "targeted" because they are "among those few countries which enjoy real independence".[224]

According to Syrian opposition sources, North Korea has sent army units to fight on behalf of Assad in the Syrian civil war.[225]

In 2018, the UN exposed North Korea for their facilitation of Syria's development of chemical weapons. According to a report by UN investigators, North Korea provided the Syrian government with acid-resistant tiles, valves, and thermometers. Additionally, DPRK missile technicians had been seen inside various Syrian chemical weapons facilities. This series of about 40 unreported shipments between North Korea and Syria, on which were the chemical weapons materials as well as prohibited ballistic missile parts, is said to have occurred throughout 2012–2017.

Al-Qaeda and ISIL

In 2001, Assad condemned the September 11 attacks.[226] In 2003, Assad said in an interview with a Kuwaiti newspaper that he doubted the organization of al-Qaeda even existed. He was quoted as saying, "Is there really an entity called al-Qaeda? Was it in Afghanistan? Does it exist now?" He remarked about Osama bin Laden, commenting: "[he] cannot talk on the phone or use the Internet, but he can direct communications to the four corners of the world? This is illogical."[227]

Assad's relationship with al-Qaeda and the ISIL has been subject to much attention. In 2014, journalist and terrorism expert Peter R. Neumann maintained, citing Syrian records captured by the U.S. military in the Iraqi border town of Sinjar and leaked State Department cables, that "in the years that preceded the uprising, Assad and his intelligence services took the view that jihad could be nurtured and manipulated to serve the Syrian government's aims".[228] Other leaked cables contained remarks by U.S. general David Petraeus which stated that "Bashar al-Asad was well aware that his brother-in-law 'Asif Shawqat, Director of Syrian Military Intelligence, had detailed knowledge of the activities of AQI facilitator Abu Ghadiya, who was using Syrian territory to bring foreign fighters and suicide bombers into Iraq", with later cables adding that Petraeus thought that "in time, these fighters will turn on their Syrian hosts and begin conducting attacks against Bashar al-Assad's regime itself".[229]

During the Iraq War, the Assad government was accused of training jihadis and facilitating their passage into Iraq, with these infiltration routes remaining active until the Syrian civil war; U.S. General Jack Keane has stated that "Al Qaeda fighters who are back in Syria, I am confident, they are relying on much they learned in moving through Syria into Iraq for more than five years when they were waging war against the U.S. and Iraq Security Assistance Force".[230] Iraqi president Nouri al-Maliki threatened Assad with an international tribunal over the matter, and ultimately lead to the 2008 Abu Kamal raid, and U.S. airstrikes within Syria during the Iraq War.[231]

During the Syrian civil war, multiple opposition and anti-Assad parties in the conflict accused Assad of collusion with ISIS; several sources have claimed that ISIS prisoners were strategically released from Syrian prisons at the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011.[232] It has also been reported that the Syrian government has bought oil directly from ISIL.[233] A businessman operating in both government and ISIL-controlled territory has claimed that "out of necessity" the Assad government has "had dealings with ISIS."[234] At its height, ISIS was making $40 million a month from the sale of oil, with spreadsheets and accounts kept by oil boss Abu Sayyaf suggesting the majority of the oil was sold to the Syrian government.[235][233] In 2014, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry claimed that the Assad government has tactically avoided ISIS forces in order to weaken "moderate opposition" such as the Free Syrian Army,[236] as well as "purposely ceding some territory to them [ISIS] in order to make them more of a problem so he can make the argument that he is somehow the protector against them".[237] A Jane's Defence Weekly database analysis claimed that only a small percentage of the Syrian government's attacks were targeted at ISIS in 2014.[238] The Syrian National Coalition has stated that the Assad government has operatives inside ISIS,[239] as has the leadership of Ahrar al-Sham.[240] ISIS members captured by the FSA have claimed that they were directed to commit attacks by Assad regime operatives.[241] Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi disputed such assertions in February 2014, arguing that "ISIS has a record of fighting the regime on multiple fronts", many rebel factions have engaged in oil sales to the Syrian regime because it is "now largely dependent on Iraqi oil imports via Lebanese and Egyptian third-party intermediaries", and while "the regime is focusing its airstrikes [on areas] where it has some real expectations of advancing" claims that it "has not hit ISIS strongholds" are "untrue". He concluded: "Attempting to prove an ISIS-regime conspiracy without any conclusive evidence is unhelpful, because it draws attention away from the real reasons why ISIS grew and gained such prominence: namely, rebel groups tolerated ISIS."[242] Similarly, Max Abrahms and John Glaser stated in the Los Angeles Times in December 2017 that "The evidence of Assad sponsoring Islamic State ... was about as strong as for Saddam Hussein sponsoring Al Qaeda."[243]

In October 2014, U.S. Vice President Joe Biden stated that Turkey, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates had "poured hundreds of millions of dollars and tens of thousands of tons of weapons into anyone who would fight against Al-Assad, except that the people who were being supplied were al-Nusra, and al Qaeda, and the extremist elements of jihadis coming from other parts of the world."[244]

Mark Lyall Grant, then Permanent Representative of the UK to the UN, stated at the outset of the American-led intervention in Syria that "ISIS is a monster that the Frankenstein of Assad has largely created".[245] French President François Hollande stated, "Assad cannot be a partner in the fight against terrorism, he is the de facto ally of jihadists".[246] Analyst Noah Bonsey of the International Crisis Group has suggested that ISIS are politically expedient for Assad, as "the threat of ISIS provides a way out [for Assad] because the regime believes that over time the U.S. and other countries backing the opposition will eventually conclude that the regime is a necessary partner on the ground in confronting this jihadi threat", while Robin Wright of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars has stated "the outside world's decision to focus on ISIS has ironically lessened the pressure on Assad."[247] In May 2015, Mario Abou Zeid of the Carnegie Middle East Center claimed that the recent Hezbollah offensive "has exposed the reality of the ISIL in Qalamoun; that it is operated by the Syrian regime's intelligence", after ISIS in the region engaged in probing attacks against FSA units at the outset of the fighting.[248]

On 1 June 2015, the U.S. stated that the Assad government was "making air-strikes in support" of an ISIS advance on Syrian opposition positions north of Aleppo.[249] Referring to the same ISIS offensive, the president of the Syrian National Coalition (SNC) Khaled Koja accused Assad of acting "as an air force for ISIS",[250] with the Defence Minister of the SNC Salim Idris claiming that approximately 180 Assad-linked officers were serving in ISIS and coordinating the group's attacks with the Syrian Arab Army.[251] Christopher Kozak of the Institute for the Study of War claims that "Assad sees the defeat of ISIS in the long term and prioritizes in the more short-and medium-term, trying to cripple the more mainline Syrian opposition [...] ISIS is a threat that lots of people can rally around and even if the regime trades … territory that was in rebel hands over to ISIS control, that weakens the opposition, which has more legitimacy [than ISIS]".[252]

In 2015, the al-Nusra Front, al-Qaeda's Syrian affiliate,[253] issued a bounty worth millions of dollars for the killing of Assad.[254] The head of the al-Nusra Front, Abu Mohammad al-Julani, said he would pay "three million euros ($3.4 million) for anyone who can kill Bashar al-Assad and end his story".[255] In 2015, Assad's main regional opponents, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey, were openly backing the Army of Conquest, an umbrella rebel group that reportedly included the al-Qaeda linked al-Nusra Front and another Salafi coalition known as Ahrar al-Sham.[256][257][258] In the course of the conflict, ISIS has repeatedly massacred pro-government Alawite civilians and executed captured Syrian Alawite soldiers,[259][260] with most Alawites supporting Bashar al-Assad, himself an Alawite. ISIS, al-Nusra Front and affiliated jihadist groups reportedly took the lead in an offensive on Alawite villages in Latakia Governorate of Syria in August 2013.[259][261]

During the interview with Jeremy Bowen in February 2015, Assad noted that the sources of the extreme ideology of Islamic State (ISIS) and other al-Qaeda affiliate groups are the Wahabbism that has been supported by kingdom of Saudi Arabia.[262]

Assad condemned the November 2015 Paris attacks, but added that France's support for Syrian rebel groups had contributed to the spread of terrorism, and rejected sharing intelligence on terrorist threats with French authorities unless France altered its foreign policy on Syria.[263][264]

Public life

Domestic opposition and support

During the civil war, the Druze in Syria have primarily sought to remain neutral, "seeking to stay out of the conflict", while according to others over half support the Assad government despite its relative weakness in Druze areas.[265] The "Sheikhs of Dignity" movement, which had sought to remain neutral and to defend Druze areas,[266] blamed the government after its leader Sheikh Wahid al-Balous was assassinated and led to large scale protests which left six government security personnel dead.[267]

It has been reported at various stages of the Syrian civil war that other religious minorities such as the Alawites and Christians in Syria favour the Assad government because of its secularism,[268][269] however opposition exists among Assyrian Christians who have claimed that the Assad government seeks to use them as "puppets" and deny their distinct ethnicity, which is non-Arab.[270] Syria's Alawite community is considered in the foreign media to be Bashar al-Assad's core support base and is said to dominate the government's security apparatus,[271][272] yet in April 2016, BBC News reported that Alawite leaders released a document seeking to distance themselves from Assad.[273]

In 2014, the Christian Syriac Military Council, the largest Christian organization in Syria, allied with the Free Syrian Army opposed to Assad,[274] joining other Syrian Christian militias such as the Sutoro who had joined the Syrian opposition against the Assad government.[275]

In June 2014, Assad won a disputed presidential election held in government-controlled areas (and ignored in opposition-held areas[276] and Kurdish areas governed by the Democratic Union Party[277]) with 88.7% of the vote. Turnout was estimated to be 73.42% of eligible voters, including those in rebel-controlled areas.[278] Individuals interviewed in a "Sunni-dominated, middle-class neighborhood of central Damascus" said there was significant support for Assad among the Sunnis in Syria.[279] Attempts to hold an election under the circumstances of an ongoing civil war were criticised by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon.[280]

Right-wing

Assad's support from the right-wing has mostly been from the far-right, both before and during the Syrian civil war. David Duke hosted a televised speech on Syrian national television in 2005.[281] Georgy Shchokin was invited to Syria in 2006 by the Syrian foreign minister and awarded a medal by the Ba'ath party, while Shchokin's institution the Interregional Academy of Personnel Management awarded Assad an honorary doctorate.[282] In 2014, the Simon Wiesenthal Center claimed that Bashar al-Assad had sheltered Alois Brunner in Syria, and alleged that Brunner advised the Assad government on purging Syria's Jewish community.[283][284]

The National Rally in France has been a prominent supporter of Assad since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war,[285] as has the former leader of the Third Way.[281] In Italy, the parties New Front and CasaPound have both been supportive of Assad, with the New Front putting up pro-Assad posters and the party's leader praising Assad's commitment to the ideology of Arab nationalism in 2013,[286] while CasaPound has also issued statements of support for Assad.[287] Syrian Social Nationalist Party representative Ouday Ramadan has worked in Italy to organize support movements for Assad.[288] Other political parties expressing support for Assad include the National Democratic Party of Germany,[289] the National Revival of Poland,[281] the Freedom Party of Austria,[290] the Bulgarian Ataka party,[291] the Hungarian Jobbik party,[292] the Serbian Radical Party,[293] the Portuguese National Renovator Party,[294] as well as the Spanish Falange Española de las JONS[295] and Authentic Falange parties.[296] The Greek neo-Nazi political party Golden Dawn has spoken out in favour of Assad,[297] and the Strasserist group Black Lily has claimed to have sent mercenaries to Syria to fight alongside the Syrian army.[298]

Nick Griffin, the former leader of the British National Party, was chosen by the Assad government to represent the UK as an ambassador and at government-held conferences; Griffin has been an official guest of the Syrian government three times since the beginning of the civil war.[299] The European Solidarity Front for Syria, representing several far-right political groups from across Europe, has had their delegations received by the Syrian national parliament, with one delegation being met by Syrian Head of Parliament Mohammad Jihad al-Laham, Prime Minister Wael Nader al-Halqi and Deputy Foreign Minister Faisal Mekdad.[288] In March 2015, Assad met with Filip Dewinter of the Belgian party Vlaams Belang.[300] In 2016, Assad met with a French delegation,[301] which included former leader of the youth movement of the National Front Julien Rochedy.[302]

President of Belarus Alexander Lukashenko has expressed confidence that Syria will eliminate the current crisis and continue under the leadership of President al-Assad "the fight against terrorism and foreign interference in its internal affairs".[303]

Left-wing

Left-wing support for Assad has been split since the start of the Syrian civil war;[304] the Assad government has been accused of cynically manipulating sectarian identity and anti-imperialism to continue its worst activities.[305] During a visit to the University of Damascus in November 2005, British politician George Galloway said of Assad, and of the country he leads: "For me he is the last Arab ruler, and Syria is the last Arab country. It is the fortress of the remaining dignity of the Arabs,"[306] and a "breath of fresh air".[307]

Hadash has expressed support for the government of Bashar al-Assad.[308] Chairman of the Workers' Party of Korea and Supreme Leader of North Korea Kim Jong-un has expressed support for Assad in face of a growing civil war.[309] The leader of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela and President of Venezuela Nicolás Maduro reiterated his full support for the Syrian people in their struggle for peace and reaffirms its strong condemnation of "the destabilizing actions that are still in Syria, with encouragement from members of NATO".[310] The leader of the National Liberation Front and President of Algeria, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, has sent a cable of congratulations to Assad, on the occasion of winning his presidential elections.[311] The leader of Guyana's People's Progressive Party and President of Guyana, Donald Ramotar, said that Assad's win in the presidential election was a great victory for Syria.[312] The leader of the African National Congress and President of South Africa, Jacob Zuma, congratulated Assad on winning the presidential elections.[313] The leader of the Sandinista National Liberation Front and President of Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega, has said that Assad's victory (in the presidential elections) is an important step to "attain peace in Syria and a clear cut evidence that the Syrian people trust their president as a national leader and support his policies which aim at maintaining Syria's sovereignty and unity".[314] The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine supports the Assad government.[315][316] The leader of Fatah and President of the State of Palestine, Mahmoud Abbas, has said that electing President Assad means "preserving Syria's unity and sovereignty and that it will help end the crisis and confront terrorism, wishing prosperity and safety to Syria".[317][318][319]

International public relations

In order to promote their image and media-portrayal overseas, Bashar al-Assad and his wife Asma al-Assad hired U.S. and UK based PR firms and consultants.[320] In particular, these secured photoshoots for Asma al-Assad with fashion and celebrity magazines, including Vogue's March 2011 "A Rose in the Desert".[321][322] These firms included Bell Pottinger and Brown Lloyd James, with the latter being paid $5,000 a month for their services.[320][323]

At the outset of the Syrian civil war, Syrian government networks were hacked by the group Anonymous, revealing that an ex-Al Jazeera journalist had been hired to advise Assad on how to manipulate the public opinion of the U.S. Among the advice was the suggestion to compare the popular uprising against the regime to the Occupy Wall Street protests.[324] In a separate e-mail leak several months later by the Supreme Council of the Syrian Revolution, which were published by The Guardian, it was revealed that Assad's consultants had coordinated with an Iranian government media advisor.[325] In March 2015, an expanded version of the aforementioned leaks was handed to the Lebanese NOW News website and published the following month.[326]

After the Syrian civil war began, the Assads started a social media campaign which included building a presence on Facebook, YouTube, and most notably Instagram.[323] A Twitter account for Assad was reportedly activated, however it remained unverified.[327] This resulted in much criticism, and was described by The Atlantic Wire as "a propaganda campaign that ultimately has made the [Assad] family look worse".[328] The Assad government has also allegedly arrested activists for creating Facebook groups that the government disapproved of,[103] and has appealed directly to Twitter to remove accounts it disliked.[329] The social media campaign, as well as the previously leaked e-mails, led to comparisons with Hannah Arendt's A Report on the Banality of Evil by The Guardian, The New York Times and the Financial Times.[330][331][332]

In October 2014, 27,000 photographs depicting torture committed by the Assad government were put on display at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.[333][334] Lawyers were hired to write a report on the images by the British law firm Carter-Ruck, which in turn was funded by the Government of Qatar.[335]

In November 2014, the Quilliam Foundation reported that a propaganda campaign, which they claimed had the "full backing of Assad", spread false reports about the deaths of Western-born jihadists in order to deflect attention from the government's alleged war crimes. Using a picture of a Chechen fighter from the Second Chechen War, pro-Assad media reports disseminated to Western media outlets, leading them to publish a false story regarding the death of a non-existent British jihadist.[336]

In 2015, Russia intervened in the Syrian civil war in support of Assad, and on 21 October 2015, Assad flew to Moscow and met with Russian president Vladimir Putin, who said regarding the civil war: "this decision can be made only by the Syrian people. Syria is a friendly country. And we are ready to support it not only militarily but politically as well."[337]

Personal life

Assad speaks fluent English and basic conversational French, having studied at the Franco-Arab al-Hurriyah school in Damascus.[338]

In December 2000, Assad married Asma Akhras, a British citizen of Syrian origin from Acton, London.[339][340] In 2001, Asma gave birth to their first child, a son named Hafez after the child's grandfather Hafez al-Assad. Their daughter Zein was born in 2003, followed by their second son Karim in 2004.[38] In January 2013, Assad stated in an interview that his wife was pregnant;[341][342] however, there were no later reports of them having a fourth child.

Bashar is an Alawite Muslim.[343]

Assad's sister, Bushra al-Assad, and mother, Anisa Makhlouf, left Syria in 2012 and 2013, respectively, to live in the United Arab Emirates.[38] Makhlouf died in Damascus in 2016.[344]

On 8 March 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Assad and his wife both tested positive for COVID-19 according to the presidential office. They were reported to be in good health with "minor symptoms".[345] On 30 March, it was announced that both had recovered and tested negative for the disease.[346]

Distinctions

Revoked and returned distinctions.

| Ribbon | Distinction | Country | Date | Location | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Cross of the National Order of the Legion of Honour | 25 June 2001 | Paris | Highest rank in the Order of the Legion of Honor in the Republic of France. Returned by Assad on 20 April 2018[347] after the opening of a revocation process by the President of the Republic, Emmanuel Macron, on 16 April 2018. | [348][349] | ||

| Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise | 21 April 2002 | Kyiv | [350] | |||

| Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Francis I | 21 March 2004 | Damascus | Dynastic order of the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies; Revoked several years later by Prince Carlo, Duke of Castro. | [351][352] | ||

| Order of Zayed | 31 May 2008 | Abu Dhabi | Highest civil decoration in the United Arab Emirates. | [353] | ||

| Order of the White Rose of Finland | 5 October 2009 | Damascus | One of three official orders in Finland. | [354] | ||

| Order of King Abdulaziz | 8 October 2009 | Damascus | Highest Saudi state order. | [355] | ||

| Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic | 11 March 2010 | Damascus | Highest ranking honour of the Republic of Italy. Revoked by the President of the Republic, Giorgio Napolitano, on 28 September 2012 for "indignity". | [356][357] | ||

| Collar of the Order of the Liberator | 28 June 2010 | Caracas | Highest Venezuelan state order. | [358] | ||

| Grand Collar of the Order of the Southern Cross | 30 June 2010 | Brasília | Brazil's highest order of merit. | [359] | ||

| Grand Cordon of the National Order of the Cedar | 31 July 2010 | Beirut | Second highest honour of Lebanon. | [360] | ||

| Order of the Islamic Republic of Iran | 2 October 2010 | Tehran | Highest national medal of Iran. | [361][362] | ||

| Uatsamonga Order | 2018 | Damascus | State award of South Ossetia. | [363] |

See also

- List of international presidential trips made by Bashar al-Assad

- Presidency of Hafez al-Assad

Explanatory notes

- /bəˈʃɑːr ˌæl.əˈsɑːd/; Arabic: بَشَّارُ حَافِظِ ٱلْأَسَدِ, Baššār Ḥāfiẓ al-ʾAsad, Levantine pronunciation: [baʃˈʃaːr ˈħaːfezˤ elˈʔasad];

English pronunciation

English pronunciation - Sources characterising the Assad family's rule of Syria as a personalist dictatorship:[3][4][5][6][7][8]

- Sources:[9][10][11][12][13][14]

- Sources:[15][16][17][18][19][20]

References

Citations

- "¿Quién es el presidente de Siria Bashar al Assad?" [Who is the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad?]. CNN en Español (in Spanish). 10 April 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Leverett 2005, p. 60.

- Svolik, Milan. "The Politics of Authoritarian Rule". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Weeks, Jessica (2014). Dictators at War and Peace. Cornell University Press. p. 18.

- Wedeen, Lisa (2018). Authoritarian Apprehensions. University of Chicago Press.

- Hinnebusch, Raymond (2012). "Syria: from 'authoritarian upgrading' to revolution?". International Affairs. 88 (1): 95–113. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01059.x.

- Michalik, Susanne (2015). "Measuring Authoritarian Regimes with Multiparty Elections". In Michalik, Susanne (ed.). Multiparty Elections in Authoritarian Regimes. Multiparty Elections in Authoritarian Regimes: Explaining their Introduction and Effects. Studien zur Neuen Politischen Ökonomie. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. pp. 33–45. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-09511-6_3. ISBN 9783658095116.

- Geddes, Barbara; Wright, Joseph; Frantz, Erica (2018). How Dictatorships Work. Cambridge University Press. p. 233. doi:10.1017/9781316336182. ISBN 978-1-316-33618-2. S2CID 226899229.

- "Syrians Vote For Assad in Uncontested Referendum". The Washington Post. Damascus. Associated Press. 28 May 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Yacoub Oweis, Khaleb (17 May 2007). "Syria's opposition boycotts vote on Assad". Reuters. Damascus. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- Klatell, James (27 May 2007). "Syrians Vote in Presidential Referendum". CBS News.

- Chulov, Martin (14 April 2014). "The one certainty about Syria's looming election – Assad will win" The Guardian.

- "Syria's Assad wins another term". BBC News. 29 May 2007. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "Democracy Damascus style: Assad the only choice in referendum". The Guardian. 28 May 2007.

- Cheeseman, Nicholas (2019). How to Rig an Election. Yale University Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-300-24665-0. OCLC 1089560229.

- Norris, Pippa; Martinez i Coma, Ferran; Grömping, Max (2015). "The Year in Elections, 2014". Election Integrity Project.

The Syrian election ranked as worst among all the contests held during 2014.

- Jones, Mark P. (2018). Herron, Erik S; Pekkanen, Robert J; Shugart, Matthew S (eds.). "Presidential and Legislative Elections". The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190258658.001.0001. ISBN 9780190258658. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

unanimous agreement among serious scholars that... al-Assad's 2014 election... occurred within an authoritarian context.

- Makdisi, Marwan (16 July 2014). "Confident Assad launches new term in stronger position". Reuters. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Evans, Dominic (28 April 2014). "Assad seeks re-election as Syrian civil war rages". Reuters. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "UK's William Hague attacks Assad's Syria elections plan". BBC News. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "Syrians in Lebanon battle crowds to vote for Bashar al-Assad". The Guardian. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "Bashar al-Assad sworn in for a third term as Syrian president". The Daily Telegraph. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Bronner 2007, p. 63.

- "Flight of Icarus? The PYD's Precarious Rise in Syria" (PDF). International Crisis Group. 8 May 2014. p. 23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

The regime aims to compel people to take refuge in their sectarian and communitarian identities; to split each community into competing branches, dividing those who support it from those who oppose it

- Meuse, Alison (18 April 2015). "Syria's Minorities: Caught Between Sword Of ISIS And Wrath of Assad". NPR. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

Karim Bitar, a Middle East analyst at Paris think tank IRIS [...] says [...] "Minorities are often used as a shield by authoritarian regimes, who try to portray themselves as protectors and as a bulwark against radical Islam."

- Bassem Mroue (18 April 2011). "Bashar Assad Resignation Called For By Syria Sit-In Activists". HuffPost. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Arab League to offer 'safe exit' if Assad resigns". CNN. 23 July 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "UN implicates Bashar al-Assad in Syria war crimes". BBC News. 2 December 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Steve Almasy; Richard Roth. "UN: Syria responsible for sarin attack that killed scores". CNN. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Nebehay, Stephanie (10 June 2014). "Assad tops list of Syria war crimes suspects handed to ICC: former prosecutor". Reuters. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- King, Esther (2 November 2016). "Assad denies responsibility for Syrian war". Politico. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

The Syrian president maintained he was fighting to preserve his country and criticized the West for intervening. "Good government or bad, it's not your mission" to change it, he said.

- Staff writer(s) (6 October 2016). "'Bombing hospitals is a war crime,' Syria's Assad says". ITV News. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

The intense bombardment of Aleppo during an army offensive that began two weeks ago has included several strikes on hospitals, residents and medical workers there have said. But Assad denied any knowledge of such attacks, saying that there were only "allegations".

- Zisser 2007, p. 20.

- Seale & McConville 1992, p. 6.

- Mikaberidze 2013, p. 38.

- Seale, Patrick (15 June 2000). "Hafez al-Assad". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- Moosa 1987, p. 305.

- Dwyer, Mimi (8 September 2013). "Think Bashar al Assad Is Brutal? Meet His Family". The New Republic. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Bar, Shmuel (2006). "Bashar's Syria: The Regime and its Strategic Worldview" (PDF). Comparative Strategy. The Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy and Strategy Institute for Policy and Strategy. 25 (5): 16 & 379. doi:10.1080/01495930601105412. S2CID 154739379. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Dow, Nicole (18 July 2012). "Getting to know Syria's first family". CNN. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Zisser 2007, p. 21.

- Ciezadlo, Annia (19 December 2013). "Bashar Al Assad: An Intimate Profile of a Mass Murderer". The New Republic. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Khalaf, Roula (15 June 2012). "Bashar al-Assad: behind the mask". Financial Times. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Belt, Don (November 2009). "Syria". National Geographic. pp. 2, 9. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- Sachs, Susan (14 June 2000). "Man in the News; The Shy Young Doctor at Syria's Helm; Bashar al-Assad". The New York Times.

- "The enigma of Assad: How a painfully shy eye doctor turned into a murderous tyrant". 21 April 2017.

- Leverett 2005, p. 59.

- Асад Башар : биография [Bashar Assad: A Biography]. Ladno (in Russian). Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Beeston, Richard; Blanford, Nick (22 October 2005). "We are going to send him on a trip. Bye, bye Hariri. Rot in hell". The Times. London. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- "How Syria's 'Geeky' President Went From Doctor to Dictator". NBC News. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- Minahan 2002, p. 83.

- Tucker & Roberts 2008, p. 167.

- "Iran Report: June 19, 2000". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- Zisser 2007, p. 35.

- Gresh, Alain (July 2020). "Syria: the rise and rise of Doctor Bashar". Le Monde diplomatique.

- Leverett 2005, p. 61.

- Zisser 2007, p. 30.

- "CNN Transcript – Breaking News: President Hafez Al-Assad Assad of Syria Confirmed Dead". CNN. 10 June 2000. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- Ma'oz, Ginat & Winckler 1999, p. 41.

- Zisser 2007, p. 34–35.

- Blanford 2006, p. 69–70.

- Blanford 2006, p. 88.

- "Syrian President Bashar al-Assad: Facing down rebellion". BBC News. 21 October 2015.

- "The rise of Syria's controversial president Bashar al-Assad". ABC News. 7 April 2017. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- Leverett 2005, p. 80.

- Wikstrom, Cajsa. "Syria: 'A kingdom of silence'". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Ghadry, Farid N. (Winter 2005). "Syrian Reform: What Lies Beneath". Middle East Quarterly. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Outsourcing the Torture of Suspected Terrorists". The New Yorker. 14 February 2005. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "America's gulag: Syrian regime was a 'common destination' for CIA rendition". Al Bawaba. 5 February 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "A staggering map of the 54 countries that reportedly participated in the CIA's rendition program". Washington Post. 5 February 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "The Hezbollah Connection". The New York Times. 15 February 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Issacharoff, Avi (1 February 2011). "Syria's Assad: Regime strong because of my anti-Israel stance". Haaretz. Tel Aviv. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- "Rafik Hariri: In Lebanon, assassination reverberates 10 years later". The Christian Science Monitor. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- "Middle East – New Hariri report 'blames Syria'". 11 December 2005. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- "Syria". United States Department of State. 26 January 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- "Q&A: Syrian activist Suhair Atassi". Al Jazeera. 9 February 2011. Archived from the original on 12 February 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- "'Day of rage' protest urged in Syria". NBC News. 3 February 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "In Syria, Crackdown After Protests". The New York Times. 18 March 2011. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Administration Takes Additional Steps to Hold the Government of Syria Accountable for Violent Repression Against the Syrian People". United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

Today, President Obama signed an Executive Order (E.O. 13573) imposing sanctions against Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and six other senior officials of the Government of Syria in an effort to increase pressure on the Government of Syria to end its use of violence against its people and to begin a transition to a democratic system that protects the rights of the Syrian people.

- "How the U.S. message on Assad shifted". The Washington Post. 18 August 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- Oweis, Khaled Yacoub (18 May 2011). "U.S. imposes sanctions on Syria's Assad". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

The U.S. move, announced by the Treasury Department, freezes any of the Syrian officials' assets that are in the United States or otherwise fall within U.S. jurisdiction and generally bars U.S. individuals and companies from dealing with them.

- "EU imposes sanctions on President Assad". BBC News. 23 May 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Canada imposes sanctions on Syrian leaders". BBC News. 24 May 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Speech of H.E. President Bashar al-Assad at Damascus University on the situation in Syria". Syrian Arab News Agency. 21 June 2011. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012.

- Sadiki 2014, p. 413.