London, Ontario

London (pronounced /ˈlʌndən/) is a city in southwestern Ontario, Canada, along the Quebec City–Windsor Corridor. The city had a population of 422,324 according to the 2021 Canadian census. London is at the confluence of the Thames River, approximately 200 km (120 mi) from both Toronto and Detroit; and about 230 km (140 mi) from Buffalo, New York. The city of London is politically separate from Middlesex County, though it remains the county seat.

London | |

|---|---|

City (single-tier) | |

| City of London | |

From top, left to right: Downtown London skyline, Budweiser Gardens, Victoria Park, Financial District, London Normal School | |

Coat of arms | |

| Nickname: "The Forest City" | |

| Motto(s): | |

| |

London | |

| Coordinates: 42°58′03″N 81°13′57″W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| Settled | 1826 (as village) |

| Incorporated | 1855 (as city) |

| Named for | London, United Kingdom |

| Government | |

| • City Mayor | Ed Holder |

| • Governing Body | London City Council |

| • MPs | List of MPs |

| • MPPs | List of MPPs |

| Area | |

| • Land | 420.50 km2 (162.36 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 232.48 km2 (89.76 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,662.40 km2 (1,027.96 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 251 m (823 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City (single-tier) | 422,324 (15th) |

| • Density | 913.1/km2 (2,365/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 543,551 (11th) |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| Forward sortation area | N5V to N6P |

| Area codes | 519, 226, and 548 |

| GDP (London CMA) | CA$24.0 billion (2016)[6] |

| GDP per capita (London CMA) | CA$48,530 (2016) |

| Website | london |

London and the Thames were named in 1793 by John Graves Simcoe, who proposed the site for the capital city of Upper Canada. The first European settlement was between 1801 and 1804 by Peter Hagerman.[7] The village was founded in 1826 and incorporated in 1855. Since then, London has grown to be the largest southwestern Ontario municipality and Canada's 11th largest metropolitan area, having annexed many of the smaller communities that surround it.

London is a regional centre of healthcare and education, being home to the University of Western Ontario (which brands itself "Western University"), Fanshawe College, and three major hospitals: Victoria Hospital, University Hospital and St. Joseph’s Hospital. The city hosts a number of musical and artistic exhibits and festivals, which contribute to its tourism industry, but its economic activity is centered on education, medical research, manufacturing, financial services, and information technology. London's university and hospitals are among its top ten employers. London lies at the junction of highways 401 and 402, connecting it to Toronto, Windsor, and Sarnia. These highways also make the Detroit-Windsor, Port Huron-Sarnia, and Niagara Falls border crossings with the United States easily accessible. The city also has an international airport, train stations and bus stations.

Toponym

London was named for the British capital of London by John Graves Simcoe, who also named the local river the Thames, in 1793.[8] Simcoe had intended London to be the capital of Upper Canada. Guy Carleton (Governor Dorchester) rejected that plan after the War of 1812,[9] but accepted Simcoe's second choice, the present site of Toronto, to become the capital city of what would become the Province of Ontario, at Confederation, on 1 July 1867.[10]

History

A series of archaeological sites throughout southwestern Ontario, named for the Parkhill Complex excavated near Parkhill, indicate the presence of Paleo-Indians in the area dating back approximately 11,000 years.[11][12] Just prior to European settlement, the London area was the site of several Attawandaron, Odawa, and Ojibwe villages. The Lawson Site in northwest London is an archaeological excavation and partial reconstruction of an approximately 500-year-old Neutral Iroquoian village, estimated to have been home to 2,000 people.[13][14] These groups were driven out by the Iroquois by c. 1654 in the Beaver Wars. The Iroquois abandoned the region some 50 years later, driven out by the Ojibwa.[15] London is also situated on the traditional lands of the Anishinaabeg,[16] One Anishinaabe community site was described as located near the forks of Thames River (Anishinaabe language: Eshkani-ziibi, "Antler River") in circa 1690[17] and was referred to as Pahkatequayang[18] ("Baketigweyaang":"At the River Fork" (lit: at where the by-stream is)).

Later, in the early 19th century, the Munsee-Delaware Nation (the Munsee are a subtribe of the Lenape or Delaware people), expelled from their homeland in Modern New Jersey and Eastern Pennsylvania after the creation of the United States.

The Oneida Nation of the Thames, Chippewas of the Thames First Nation, and Munsee-Delaware Nation reserves are located south-west of the city.

Settlement

The current location of London was selected as the site of the future capital of Upper Canada in 1793 by Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe, who also named the village which was founded in 1826.[8] Originally, Simcoe had proposed to call it Georgiana, in honour of George III, the reigning monarch at that time.[19] It did not become the capital Simcoe envisioned. Rather, it was an administrative seat for the area west of the actual capital, York (now Toronto). The London Township Treaty of 1796 with the Chippewa ceded the original town site on the north bank of the Thames (then known as the Escunnisepe) to Upper Canada.[20][21]

London was part of the Talbot Settlement, named for Colonel Thomas Talbot, the chief administrator of the area, who oversaw the land surveying and built the first government buildings for the administration of the western Ontario peninsular region. Together with the rest of southwestern Ontario, the village benefited from Talbot's provisions not only for building and maintaining roads but also for assignment of access priorities to main routes to productive land.[22] Crown and clergy reserves then received preference in the rest of Ontario.

In 1814, the Battle of Longwoods took place during the War of 1812 in what is now Southwest Middlesex, near London.[23]

In 1832, the new settlement suffered an outbreak of cholera.[24] London proved a centre of strong Tory support during the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837, notwithstanding a brief rebellion led by Charles Duncombe. Consequently, the British government located its Ontario peninsular garrison there in 1838, increasing its population with soldiers and their dependents, and the business support populations they required.[22] London was incorporated as a town in 1840.[24]

On 13 April 1845, a fire destroyed much of London, which was then largely constructed of wooden buildings.[25] One of the first casualties was the town's only fire engine. The fire burned nearly 30 acres (12 ha) of land, destroying 150 buildings, before it burned itself out later that day. One fifth of London was destroyed in the province's first million-dollar fire.[26]

Development

John Carling, Tory MP for London, gave three events to explain the development of London in a 1901 speech: the location of the court and administration in London in 1826, the arrival of the military garrison in 1838, and the arrival of the railway in 1853.[27]

The population in 1846 was 3,500. Brick buildings included a jail and court house, and large barracks. London had a fire company, a theatre, a large Gothic church, nine other churches or chapels, and two market buildings. The buildings that were destroyed by fire in 1845 were mostly rebuilt by 1846. Connection with other communities was by road, using mainly stagecoaches that ran daily. A weekly newspaper was published and mail was received daily by the post office.[28]

On 1 January 1855, London was incorporated as a city (10,000 or more residents).[22] In the 1860s, a sulphur spring was discovered at the forks of the Thames River while industrialists were drilling for oil.[29] The springs became a popular destination for wealthy Ontarians, until the turn of the 20th century when a textile factory was built at the site, replacing the spa.

Records from 1869 indicate a population of about 18,000 served by three newspapers, churches of all major denominations and offices of all the major banks. Industry included several tanneries, oil refineries and foundries, four flour mills, the Labatt Brewing Company and the Carling brewery in addition to other manufacturing. Both the Great Western and Grand Trunk railways had stops here. Several insurance companies also had offices in the city.

The Crystal Palace Barracks, an octagonal brick building with eight doors and forty-eight windows built in 1861, was used for events such the Provincial Agricultural Fair of Canada West held in London that year. It was visited by Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, Governor-General John Young, 1st Baron Lisgar and Prime Minister John A. Macdonald.[30][31]

Long before the Royal Military College of Canada was established in 1876, there were proposals for military colleges in Canada. Staffed by British Regulars, adult male students underwent three-month-long military courses from 1865 at the School of Military Instruction in London. Established by Militia General Order in 1865, the school enabled Officers of Militia or Candidates for Commission or promotion in the Militia to learn Military duties, drill and discipline, to command a Company at Battalion Drill, to Drill a Company at Company Drill, the internal economy of a Company and the duties of a Company's Officer.[32] The school was not retained at Confederation, in 1867.[33]

In 1875, London's first iron bridge, the Blackfriars Street Bridge, was constructed.[25] It replaced a succession of flood-failed wooden structures that had provided the city's only northern road crossing of the river. A rare example of a wrought iron bowstring arch through truss bridge, the Blackfriars remains open to pedestrian and bicycle traffic, though it was temporarily closed indefinitely to vehicular traffic due to various structural problems[34] and was once again reopened to vehicular traffic 1 December 2018, see Blackfriars Bridge Grand Opening. The Blackfriars, amidst the river-distance between the Carling Brewery and the historic Tecumseh Park (including a major mill), linked London with its western suburb of Petersville, named for Squire Peters of Grosvenor Lodge. That community joined with the southern subdivision of Kensington in 1874, formally incorporating as the municipality of Petersville. Although it changed its name in 1880 to the more inclusive "London West", it remained a separate municipality until ratepayers voted for amalgamation with London in 1897,[22] largely due to repeated flooding. The most serious flood was in July 1883, which resulted in serious loss of life and property devaluation.[35] This area retains much original and attractively maintained 19th-century tradespeople's and workers' housing, including Georgian cottages as well as larger houses, and a distinct sense of place.

London's eastern suburb, London East, was (and remains) an industrial centre, which also incorporated in 1874.[22] Attaining the status of town in 1881,[36] it continued as a separate municipality until concerns over expensive waterworks and other fiscal problems led to amalgamation in 1885.[37] The southern suburb of London, including Wortley Village, was collectively known as "London South". Never incorporated, the South was annexed to the city in 1890,[22] although Wortley Village still retains a distinct sense of place. By contrast, the settlement at Broughdale on the city's north end had a clear identity, adjoined the university, and was not annexed until 1961.[38]

Ivor F. Goodson and Ian R. Dowbiggin have explored the battle over vocational education in London, Ontario, in the 1900–1930 era. The London Technical and Commercial High School came under heavy attack from the city's social and business elite, which saw the school as a threat to the budget of the city's only academic high school, London Collegiate Institute.[39]

London's role as a military centre continued into the 20th century during the two World Wars, serving as the administrative centre for the Western Ontario district. In 1905, the London Armoury was built and housed the First Hussars until 1975. A private investor purchased the historic site and built a new hotel (Delta London Armouries, 1996) in its place, preserving the shell of the historic building. In the 1950s, two reserve battalions amalgamated and became London and Oxford Rifles (3rd Battalion), The Royal Canadian Regiment.[40] This unit continues to serve today as 4th Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment. The Regimental Headquarters of The Royal Canadian Regiment remains in London at Wolseley Barracks on Oxford Street. The barracks are home to the First Hussars militia regiment as well.[40]

Annexation to present

London annexed many of the surrounding communities in 1961, including Byron and Masonville, adding 60,000 people and more than doubling its area.[22] After this amalgamation, suburban growth accelerated as London grew outward in all directions, creating expansive new subdivisions such as Westmount, Oakridge, Whitehills, Pond Mills, White Oaks and Stoneybrook.[22]

On 1 January 1993, London annexed nearly the entire township of Westminster, a large, primarily rural municipality directly south of the city, including the police village of Lambeth.[41] With this massive annexation, which also included part of London township, London almost doubled in area again, adding several thousand more residents. In the present day, London stretches south to the boundary with Elgin County, north and east to Fanshawe Lake, north and west to the township of Middlesex Centre (the nearest developed areas of it being Arva to the north and Komoka to the west) and east to Nilestown and Dorchester.

The 1993 annexation, made London one of the largest urban municipalities in Ontario.[42] Intense commercial and residential development is presently occurring in the southwest and northwest areas of the city. Opponents of this development cite urban sprawl,[43] destruction of rare Carolinian zone forest and farm lands,[44] replacement of distinctive regions by generic malls, and standard transportation and pollution concerns as major issues facing London. The City of London is currently the eleventh-largest urban area in Canada, eleventh-largest census metropolitan area in Canada, and the sixth-largest city in Ontario.[45][46]

Disasters

On Victoria Day, 24 May 1881, the stern-wheeler ferry SS Victoria capsized in the Thames River close to Cove Bridge in West London. Approximately 200 passengers drowned in the shallow river, making it one of the worst disasters in London's history, and is now dubbed "The Victoria Day Disaster". At the time, London's population was relatively low; therefore it was hard to find a person in the city who did not have a family member affected by the tragedy.

Two years later, on 12 July 1883,[25] the first of the two most devastating floods in London's history killed 17 people. The second major flood, on 26 April 1937, destroyed more than a thousand houses across London, and caused over $50 million in damages, particularly in West London.[47][48]

On 3 January 1898, the floor of the assembly hall at London City Hall collapsed, killing 23 people and leaving more than 70 injured. Testimony at a coroner's inquest described the wooden beam under the floor as unsound, with knots and other defects reducing its strength by one fifth to one third.[49]

After repeated floods, the Upper Thames River Conservation Authority in 1953 built Fanshawe Dam on the North Thames to control the downstream rivers.[50] Financing for this project came from the federal, provincial, and municipal governments. Other natural disasters include a 1984 tornado that led to damage on several streets in the White Oaks area of South London.[51]

On 11 December 2020, a partially-constructed apartment building just off of Wonderland Road in southwest London collapsed, killing two people and injuring at least four others.[52][53] As late August 2021, the investigation is still ongoing.[54][55]

On 6 June 2021, a man rammed a pickup truck into Muslim Pakistani Canadian pedestrians at an intersection in London.[56] Four people were killed, and another was wounded, all from the same family.[57] The attack was the largest mass killing in London's history.[58]

Geography

The area was formed during the retreat of the glaciers during the last ice age, which produced areas of marshland, notably the Sifton Bog, as well as some of the most agriculturally productive areas of farmland in Ontario.[59] The Thames River dominates London's geography. The North and South branches of the Thames River meet at the centre of the city, a location known as "The Forks" or "The Fork of the Thames."[60] The North Thames runs through the man-made Fanshawe Lake in northeast London. Fanshawe Lake was created by Fanshawe Dam, constructed to protect the downriver areas from the catastrophic flooding which affected the city in 1883 and 1937.[61]

Climate

London has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb), though due to its downwind location relative to Lake Huron and elevation changes across the city, it is virtually on the Dfa/Dfb (hot summer) boundary favouring the former climate zone to the southwest of the confluence of the South and North Thames Rivers, and the latter zone to the northeast (including the airport). Because of its location in the continent, London experiences large seasonal contrast, tempered to a point by the surrounding Great Lakes. The summers are usually warm to hot and humid, with a July average of 20.8 °C (69.4 °F), and temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F) occur on average 10 days per year.[62] In 2016, however, temperatures at or above 30 °C (86 °F) occurred more than 35 times, and in 2018, four heatwave incidents led to humidex temperatures topping out at 46 °C (115 °F) . The city is affected by frequent thunderstorms due to hot, humid summer weather, as well as the convergence of breezes originating from Lake Huron and Lake Erie. The same convergence zone is responsible for spawning funnel clouds and the occasional tornado. Spring and autumn in between are not long, and winters are cold but witness frequent thaws. Annual precipitation averages 1,011.5 mm (39.82 in). Its winter snowfall totals are heavy, averaging about 194 cm (76 in) per year,[62] although the localized nature of snow squalls means the total can vary widely from year to year.[63] The majority of snow accumulation comes from lake effect snow and snow squalls originating from Lake Huron, some 60 km (37 mi) to the northwest, which occurs when strong, cold winds blow from that direction. From 5 December 2010, to 9 December 2010, London experienced record snowfall when up to 2 m (79 in) of snow fell in parts of the city. Schools and businesses were closed for three days and bus service was cancelled after the second day of snow.[64]

The highest temperature ever recorded in London was 41.1 °C (106 °F) on 6 August 1918.[65][66] The lowest temperature ever recorded was −32.8 °C (−27 °F) on 9 February 1934.[65]

| Climate data for London, Ontario (London International Airport), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1871–present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.7 (62.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

27.5 (81.5) |

30.6 (87.1) |

34.4 (93.9) |

38.2 (100.8) |

38.9 (102.0) |

41.1 (106.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

30.3 (86.5) |

24.4 (75.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

41.1 (106.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1.9 (28.6) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.3 (77.5) |

21.1 (70.0) |

14.2 (57.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

0.9 (33.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −5.6 (21.9) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

19.7 (67.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −9.2 (15.4) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

14.0 (57.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −32.2 (−26.0) |

−32.8 (−27.0) |

−28.3 (−18.9) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−30.0 (−22.0) |

−32.8 (−27.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 74.2 (2.92) |

65.5 (2.58) |

71.5 (2.81) |

83.4 (3.28) |

89.8 (3.54) |

91.7 (3.61) |

82.7 (3.26) |

82.9 (3.26) |

103.0 (4.06) |

81.3 (3.20) |

98.0 (3.86) |

87.5 (3.44) |

1,011.5 (39.82) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 33.4 (1.31) |

33.6 (1.32) |

46.3 (1.82) |

74.7 (2.94) |

89.4 (3.52) |

91.7 (3.61) |

82.7 (3.26) |

82.9 (3.26) |

103.0 (4.06) |

78.1 (3.07) |

83.2 (3.28) |

46.9 (1.85) |

845.9 (33.30) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 49.3 (19.4) |

38.4 (15.1) |

29.4 (11.6) |

9.4 (3.7) |

0.4 (0.2) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

3.2 (1.3) |

16.6 (6.5) |

47.6 (18.7) |

194.3 (76.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 18.8 | 15.1 | 15.3 | 14.1 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 12.1 | 13.1 | 15.8 | 18.0 | 168.0 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 6.3 | 5.4 | 8.3 | 12.0 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 11.3 | 10.4 | 12.1 | 13.0 | 11.6 | 7.8 | 122.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 15.3 | 12.1 | 9.1 | 3.5 | 0.18 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 5.7 | 13.2 | 60.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75.9 | 71.9 | 65.0 | 56.9 | 54.8 | 57.0 | 57.6 | 59.7 | 59.9 | 63.1 | 72.0 | 76.9 | 64.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 64.4 | 89.9 | 124.0 | 158.0 | 219.6 | 244.3 | 261.6 | 217.7 | 165.1 | 128.7 | 67.4 | 52.1 | 1,792.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 22.1 | 30.4 | 33.6 | 39.4 | 48.4 | 53.2 | 56.2 | 50.4 | 43.9 | 37.5 | 23.0 | 18.5 | 38.1 |

| Source: Environment Canada[62][67][65] | |||||||||||||

Parks

London has a number of parks. Victoria Park in downtown London is a major centre of community events, attracting an estimated 1 million visitors per year. Other major parks include Harris Park, Gibbons Park, Fanshawe Conservation Area (Fanshawe Pioneer Village), Springbank Park, White Oaks Park and Westminster Ponds. The city also maintains a number of gardens and conservatories.[60]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1871 | 18,000 | — |

| 1881 | 26,266 | +45.9% |

| 1891 | 31,977 | +21.7% |

| 1901 | 37,976 | +18.8% |

| 1911 | 46,509 | +22.5% |

| 1921 | 50,959 | +9.6% |

| 1931 | 71,148 | +39.6% |

| 1941 | 78,134 | +9.8% |

| 1951 | 95,343 | +22.0% |

| 1961 | 169,569 | +77.9% |

| 1966 | 194,416 | +14.7% |

| 1971 | 223,222 | +14.8% |

| 1976 | 240,392 | +7.7% |

| 1981 | 254,280 | +5.8% |

| 1986 | 269,140 | +5.8% |

| 1991 | 311,620 | +15.8% |

| 1996 | 325,699 | +4.5% |

| 2001 | 336,539 | +3.3% |

| 2006 | 352,395 | +4.7% |

| 2011 | 366,151 | +3.9% |

| 2016 | 383,822 | +4.8% |

| 2021 | 422,324 | +10.0% |

| [68][69][70][71][72][73][74] | ||

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, London had a population of 422,324 living in 174,657 of its 186,409 total private dwellings, a change of 10% from its 2016 population of 383,822. With a land area of 420.5 km2 (162.4 sq mi), it had a population density of 1,004.3/km2 (2,601.2/sq mi) in 2021.[75]

At the census metropolitan area (CMA) level in the 2021 census, the London CMA had a population of 543,551 living in 222,239 of its 235,522 total private dwellings, a change of 10% from its 2016 population of 494,069. With a land area of 2,661.48 km2 (1,027.60 sq mi), it had a population density of 204.2/km2 (529.0/sq mi) in 2021.[76]

As per the 2021 census, the most common ethnic or cultural origins in London are English (21.9%), Scottish (17.4%), Irish (16.8%), Canadian (12.1%), German (9.3%), French (6.6%), Dutch (5.0%), Italian (4.5%), British Isles (4.3%), Indian (3.7%), Polish (3.6%), and Chinese (3.0%).[77] Indigenous people made up 2.6% of the population, with most being First Nations (1.9%). Ethnocultural backgrounds in the city included European (68.7%), South Asian (6.5%), Arab (5.3%), Black (4.2%), Latin American (3.0%), Chinese (2.9%), Southeast Asian (1.4%), Filipino (1.4%), West Asian (1.3%), and Korean (1.0%).[78]

The 2021 census found English to be the mother tongue of 71.1% of the population. This was followed by Arabic (3.7%), Spanish (2.7%), Mandarin (1.6%), Portuguese (1.3%), French (1.1%), Polish (1.1%), Korean (0.8%), Punjabi (0.8%), Malayalam (0.8%), and Urdu (0.7%). Of the official languages, 98% of the population reported knowing English and 7.2% French.[79]

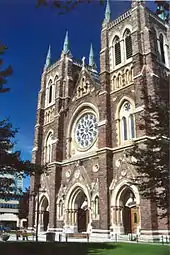

In 2021, 48.8% of the population identifed as Christian, with Catholics (21.5%) making up the largest denomination, followed by United Church (4.7%), Anglican (4.4%), Orthodox (1.8%), Presbyterian (1.5%), Baptist (1.4%), and other denominations. 37.2% of the population reported no religious affiliation. Others identified as Muslim (8.4%), Hindu (2.1%), Sikh (1.0%), Buddhist (0.9%), Jewish (0.5%), and with other religions.[80]

Economy

London's economy is dominated by medical research, financial services, manufacturing,[81] and information technology. Much of the life sciences and biotechnology related research is conducted or supported by the University of Western Ontario (partly through the Robarts Research Institute), which adds about C$1.5 billion to the London economy annually.[82] Private companies in the industry like Alimentiv, KGK Sciences and Sernova are also based in London. The largest employer in London is the London Health Sciences Centre, which employs 10,555 people.[83]

Since the economic crisis of 2009, the city has transitioned to become a technology hub with a focus on the Digital Creative sector.[84] As of 2016, London is home to 300 technology companies that employ 3% of the city's labour force.[85] Many of these companies have moved into former factories and industrial spaces in and around the downtown core, and have renovated them as modern offices. For example, Info-Tech Research Group's London office is in a hosiery factory, and Arcane Digital moved into a 1930s industrial building in 2015.[86] The Historic London Roundhouse, a steam locomotive repair shop built in 1887, is now home to Royal LePage Triland Realty, rTraction and more. Its redesign, which opened in 2015, won the 2015 Paul Oberman Award for Adaptive Re-Use from the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario.[87] London is also home to StarTech.com, Diply, video game companies like Digital Extremes, Big Blue Bubble and Big Viking Games, and Voices.com, which provides voiceover artists a platform to advertise and sell their services to those looking for voiceover work. Other tech companies located in London include AutoData, Carfax Canada, HRDownloads, Mobials, Northern Commerce and Paystone which recently raised $100M.[88]

The London Life Insurance Company was founded there,[89] as was Canada Trust (in 1864),[90] Imperial Oil,[91] GoodLife Fitness, and both the Labatt and Carling breweries. The Libro Financial Group was founded in London 1951 and is the second largest credit union in Ontario and employs over 600 people.[92] Downtown London is also home to major satellite offices for each of the Big Five banks of Canada, particularly TD Bank which employees 2,000 people, and the digital challenger bank VersaBank is also headquartered in the city.

The headquarters of the Canadian division of 3M are in London. General Dynamics Land Systems (GDLS) builds armoured personnel carriers in the city.[93] GDLS has a 14-year $15-billion deal to supply light armored vehicles and employees over 2,400 people.[94] McCormick Canada, formerly Club House Foods, was founded in 1883 and currently employs more than 600 Londoners. A portion of the city's population work in factories outside of the city limits, including the General Motors automotive plant CAMI, and a Toyota plant in Woodstock. A Ford plant in Talbotville became one of the casualties of the economic crisis in 2011,[95] the site will soon be home to a major Amazon distribution center employing 2,000 workers by 2023.[96]

London's city centre mall was first opened in 1960 as Wellington Square with 400,000 sq. ft. of leasable area, with Eaton's and Woolworths as anchors. From 1986 to 1989, Campeau expanded Wellington Square into Galleria London with 1,000,000 sq. ft. of leasable area and 200 stores including The Bay and Eaton's. However the early 1990s recession, following by the bankruptcy of Eaton's in 1999 and then the departure of The Bay in 2000 resulted in only 20 stores left by 2001. Galleria London then begun seeking non-retail tenants, becoming the home for London's central library branch, and satellite campuses for both Fanshawe College and Western University. The complex was purchased and renamed to Citi Plaza by Citigroup in 2009.[97] Citi Plaza has been redeveloped as a mixed use complex that blends retail, office, businesses, and education providers. Alongside Citi Cards Canada's offices, in November 2016, CBC announced plans to move its expanded operations into the building.[98]

On 11 December 2009, Minister of State Gary Goodyear announced a new $11-million cargo terminal at the London International Airport.[99]

Culture

Film Production

In 2021, the city established FilmLondon through the London Economic Development Corporation in order to attract film and television productions to the city as an alternative to filming in the Greater Toronto Area.[100] Notable productions that have resulted from this effort include The Amazing Race Canada 8[101] and The Changeling.[102] Notable actors born in London include Ryan Gosling, Rachel McAdams, Victor Garber, Hume Cronyn, Michael McManus, and director Paul Haggis.

Festivals

The city is home to many festivals including SunFest, the London Fringe Theatre Festival, the Forest City Film Festival, the London Ontario Live Arts Festival (LOLA), the Home County Folk Festival, Rock the Park London, Western Fair, Pride London,[103] and others. The London Rib Fest is the second largest barbecue rib festival in North America.[104] SunFest, a world music festival, is the second largest in Canada after Toronto Caribbean Carnival (Caribana) and is among the top 100 summer destinations in North America.[105]

Music

London has a rich musical history. Guy Lombardo, the internationally acclaimed Big-Band leader, was born in London, as was jazz musician Rob McConnell, country music legend Tommy Hunter, singer-songwriter Meaghan Smith, pop icon Justin Bieber, the heavy metal band Kittie, film composer Trevor Morris, and DJ duo Loud Luxury; it is also the adopted hometown of hip-hop artist Shad Kabango, rock-music producer Jack Richardson, and 1960s folk-funk band Motherlode.

American country-music icon Johnny Cash proposed to his wife June Carter Cash onstage at the London Gardens—site of the famous April 26, 1965, fifteen-minute Rolling Stones concert—during his February 22, 1968 performance in the city (the hometown of his manager Saul Holiff).

Avant-garde noise-pioneers The Nihilist Spasm Band formed in downtown London in 1965. Between 1966 and 1972, the group held a Monday night residency at the York Hotel in the city's core, which established it as a popular venue for emerging musicians and artists; known as Call the Office, the venue served as a hotbed for punk music in the late 1970s and 1980s and hosted college rock bands and weekly alternative-music nights until closing indefinitely in 2020.[106]

In 2003, CHRW-FM developed The London Music Archives, an online music database that chronicled every album recorded in London between 1966 and 2006,[107] and in 2019 the CBC released a documentary entitled "London Calling" which outlined "The Secret Musical History of London Ontario" (including its importance for the massively popular electronic-music duo Richie Hawtin and John Acquaviva). London also had (and still has, in an unofficial capacity) a professional symphony orchestra -- Orchestra London—which was founded in 1937; although the organization filed for bankruptcy in 2015, members of the orchestra continue to play self-produced concerts under the moniker London Symphonia. In addition, the city is home to the London Community Orchestra, the London Youth Symphony, and the Amabile Choirs of London, Canada. The Juno Awards of 2019 were hosted in London in March 2019, hosted by singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan. In 2021, London was named Canada's first City of Music, by UNESCO.[108] The labor union representing entertainment venue workers in London is IATSE Local 105.[109]

Art

London artists Jack Chambers and Greg Curnoe co-founded The Forest City Gallery in 1973 and the Canadian Artists' Representation society in 1968. Museum London, the city's central Art Gallery, was established in 1940 (initially operated from the London Public Library, until 1980, when Canadian architect Raymond Moriyama was commissioned to design its current home at the forks of the Thames River). London is also home to the Museum of Ontario Archaeology, owned and operated by Western University; it is Canada's only ongoing excavation and partial reconstruction of a prehistoric village—in this case, a Neutral Nation village.[110] The Royal Canadian Regiment Museum is a military museum at Wolseley Barracks (a Canadian former Forces Base in the city's Carling neighbourhood). The Secrets of Radar Museum was opened at Parkwood Hospital in 2003, and tells the story of the more than 6,000 Canadian World War II veterans who were recruited into a top-secret project during World War II involving radar. The London Regional Children's Museum in South London provides hands-on learning experiences for children and was one of the first children's museums established in Canada. The Canadian Medical Hall of Fame has its headquarters in downtown London and features a medical history museum.

Eldon House is the former residence of the prominent Harris Family and oldest surviving such building in London. The entire property was donated to the city of London in 1959 and is now a heritage site. An Ontario Historical Plaque was erected by the province to commemorate The Eldon House's role in Ontario's heritage.[111] The Banting House National Historic Site of Canada is the house where Frederick Banting developed the ideas that led to the discovery of insulin. Banting lived and practised in London for ten months, from July 1920 to May 1921. London is also the site of the Flame of Hope, which is intended to burn until a cure for diabetes is discovered.[112]

In addition to Museum London and The Forest City Gallery, London is also home to a number of other galleries and art spaces, including the McIntosh Gallery at Western University, TAP Centre for Creativity, and various smaller galleries such as the Thielsen Gallery, the Westland Gallery, the Michael Gibson Gallery, the Jonathon Bancroft-Snell Gallery, The Art Exchange, Strand Fine Art and others. London also hosts an annual Nuit Blanche every June.

Theatre

London is home to the Grand Theatre, a professional proscenium arch theatre in Central London. The building underwent renovations in 1975 to restore the stage proscenium arch and to add a secondary performance space. The architectural firm responsible for the redesign was awarded a Governor General's award in 1978 for their work on the venue. In addition to professional productions, the Grand Theatre also hosts the High School Project, a program unique to North America that provides high school students an opportunity to work with professional directors, choreographers, musical directors, and stage managers. The Palace Theatre, in Old East Village, originally opened as a silent movie theatre in 1929 and was converted to a live theatre venue in 1991.[113] It is currently the home of the London Community Players, and as of 2016 is undergoing extensive historical restoration. The Original Kids Theatre Company, a nonprofit charitable youth organisation, currently puts on productions at the Spriet Family Theatre in the Covent Garden Market.[114]

Literature

London serves as a core setting in Southern Ontario Gothic literature, most notably in the works of James Reaney. The psychologist Richard Maurice Bucke, author of Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind and Walt Whitman's literary executor, lived and worked in London, where he was often visited by Whitman[115] (the Maurice Bucke Archive are part of the Special Collections in The Weldon Library of Western University). Modern writers from this city include fantasy-fiction authors R. Scott Bakker and Kelley Armstrong, Booker Prize winner Eleanor Catton, Scotiabank Giller Prize winner Bonnie Burnard and distinguished nominee Joan Barfoot. Emma Donoghue, whose 2010 novel, Room, was adapted into a 2015 Academy Award-winning film of the same name, also lives in London. WordFest is an annual literary and creative arts festival that takes place each November.

Livability

In 2020 and 2021, house prices rose significantly across Canada, especially in Ontario. The average price of a home in Canada in March 2021 was $716,828, a 31.6% year-over-year increase.[116] Meanwhile, the average cost to purchase a home in London was $607,000 in January 2021; since then increasing to $641,072 in June 2021 according to LSTAR.[117] As the COVID-19 pandemic has begun to decrease in severity as vaccinations in Canada reach close to herd immunity, the housing market in London is showing signs of a cool-down according to some realtors.[118] In April 2021, the Bank of Canada reported that the primary reason house prices had increased to such an unprecedented extent was due to housing inventory reaching record lows.[119]

Nevertheless, the city's cost of living remains lower than many other southern Ontario cities. London is known for being a medium-sized city with big city amenities, having under 400,000 residents as of the 2016 census yet having all of the services one could find in a large city, including two large-scale shopping malls, Masonville Place and White Oaks Mall, regional health care centres, and postsecondary education hubs such as the world-class University of Western Ontario and well-known Fanshawe College. In mid-2021, London had an 8.75% cheaper cost of living, and 27.5% cheaper cost of rent, compared to nearby Toronto.[120]

London has nine major parks and gardens throughout the city, many of which run along the Thames River and are interconnected by a series of pedestrian and bike paths, known as the Thames Valley Parkway.[121] This path system is 40 km (25 mi) in length, and connects to an additional 150 km (93 mi) of bike and hiking trails throughout the city.[122] The city's largest park, Springbank Park, is 140-hectare (300 acre) and contains 30 km (19 mi) of trails. It is also home to Storybook Gardens, a family attraction open year-round.

The city includes many pedestrian walkways throughout its neighbourhoods. Newer settled areas in the northwest end of the city include long pathways between housing developments and tall grass bordering Snake Creek, a thin waterway connected to the Thames River. These walkways connect the neighbourhoods of Fox Hollow, White Hills, Sherwood Forest and the western portion of Masonville, also running through parts of Medway Valley Heritage Forest.

Sports

London is the home of the London Knights of the Ontario Hockey League, who play at the Budweiser Gardens. The Knights are 2004–2005 and 2015–2016 OHL and Memorial Cup Champions. During the summer months, the London Majors of the Intercounty Baseball League play at Labatt Park. FC London of League1 Ontario and founded in 2008 is the highest level of soccer in London. The squad plays at German Canadian Club of London Field. Other sports teams include the London Silver Dolphins Swim Team, the Forest City Volleyball Club, London Cricket Club, the London St. George's Rugby Club, the London Aquatics Club, the London Rhythmic Gymnastics Club, the London Rowing Club, London City Soccer Club and Forest City London.

The Eager Beaver Baseball Association (EBBA) is a baseball league for youths in London. It was first organized in 1955 by former Major League Baseball player Frank Colman, London sportsman Gordon Berryhill and Al Marshall.

Football teams include the London Beefeaters (Ontario Football Conference).

London's basketball team, the London Lightning plays at Budweiser Gardens as members of the National Basketball League of Canada. Finishing their inaugural regular season at 28–8, the Lightning would go on to win the 2011–12 NBL Canada championship, defeating the Halifax Rainmen in the finals three games to two.

There are also a number of former sports teams that have moved or folded. London's four former baseball teams are the London Monarchs (Canadian Baseball League), the London Werewolves (Frontier League), the London Tecumsehs (International Association) and the London Tigers (AA Eastern League). Other former sports teams include the London Lasers (Canadian Soccer League)

In March 2013, London hosted the 2013 World Figure Skating Championships. The University of Western Ontario's teams play under the name Mustangs. The university's football team plays at TD Stadium.[123] Western's Rowing Team rows out of a boathouse at Fanshawe Lake. Fanshawe College teams play under the name Falcons. The Women's Cross Country team has won 3 consecutive Canadian Collegiate Athletic Association (CCAA) National Championships.[124] In 2010, the program cemented itself as the first CCAA program to win both Men's and Women's National team titles, as well as CCAA Coach of the Year.[125]

The Western Fair Raceway, about 85 acres harness racing track and simulcast centre, operates year-round.[126] The grounds include a coin slot casino, a former IMAX theatre, and Sports and Agri-complex. Labatt Memorial Park the world's oldest continuously used baseball grounds[127][128] was established as Tecumseh Park in 1877; it was renamed in 1937, because the London field has been flooded and rebuilt twice (1883 and 1937), including a re-orientation of the bases (after the 1883 flood). The Forest City Velodrome, at the former London Ice House, is the only indoor cycling track in Ontario and the third to be built in North America, opened in 2005.[129] London is also home to World Seikido, the governing body of a martial art called Seikido which was developed in London in 1987.[130]

Current franchises

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London Knights | OHL | Ice hockey | Budweiser Gardens | 1965 | 4 |

| London Nationals | GOJHL | Ice hockey | Western Fair District | 1950 | 7 |

| London Lightning | NBL Canada | Basketball | Budweiser Gardens | 2011 | 3 |

| London Majors | IBL | Baseball | Labatt Memorial Park | 1925 | 9 |

| London St. George's RFC | ORU (Marshall Premiership) | Rugby Union | London St. George's Club | 1959 | 0 |

| FC London | League1 Ontario | Soccer | Western Alumni Stadium | 2009 | 1 |

| London Beefeaters | CJFL | Canadian Football | Western Alumni Stadium | 1975 | 1 |

| London Blue Devils | Ontario Junior B Lacrosse League | Lacrosse | Earl Nichols Recreation Centre | 2003 | 0 |

| Prospect Fighting Championships | Provincial MMA Promotion | Mixed Martial Arts | Varies | 2013 | N/A |

Current professional sports franchises

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenaline MMA training & fitness | UFC and other International promotions | Mixed Martial Arts | Adrenaline Training centre | 2001 | 1 |

| London Lightning | NBL Canada | Basketball | Budweiser Gardens | 2011 | 3 |

Government and law

London's municipal government is divided among fourteen councillors (one representing each of London's fourteen wards) and the mayor. Matt Brown was elected mayor in the 2014 municipal election, officially taking office on 1 December 2014.[131] Prior to Brown's election, London's most recent elected mayor was Joe Fontana; following Fontana's resignation on 19 June 2014, city councillor Joe Swan served as acting mayor[132] until councillor Joni Baechler was selected as interim mayor 24 June.[133] Until the elections in 2010, there was a Board of Control, consisting of four controllers and the mayor, all elected citywide.[134]

Although London has many ties to Middlesex County, it is a totally separate entity; the two have no jurisdictional overlap[since when?]. The exception is the Middlesex County courthouse and former jail, as the judiciary is administered directly by the province.[135]

London was the first city in Canada (in May 2017) to decide to move a ranked choice ballot for municipal elections starting in 2018. Voters mark their ballots in order of preference, ranking their top three favourite candidates. An individual must reach 50 per cent of the total to be declared elected; in each round of counting where a candidate has not yet reached that target, the person with the fewest votes is dropped from the ballot and their second or third choice preferences reallocated to the remaining candidates, with this process repeating until a candidate has reached 50 per cent.[136]

In 2001, the City of London first published their Facilities Accessibility Design Standards (FADS) which was one of the first North American municipal accessibility requirements to include Universal Design. It has since been adopted by over 50 municipalities in Canada and the United States.[137]

City councillors

In addition to mayor Ed Holder, the following were elected in the 2018 municipal election for the 2018–2022 term:[138]

| Councillor | Office | Communities |

|---|---|---|

| Michael van Holst | Ward 1 | Chelsea Green, Fairmont, Hamilton Road, River Run, The Gore, Glen Cairn |

| Shawn Lewis | Ward 2 | Argyle, Crumlin, Pottersburg, Nelson Park, Trafalgar Heights |

| Mo Mohamed Salih | Ward 3 | Airport, Fanshawe, Huron Heights, The Grove |

| Jesse Helmer | Ward 4 | East London |

| Maureen Cassidy | Ward 5 | Stoneybrook, Northdale, Northerest, Uplands |

| Phil Squire | Ward 6 | Broughdale, University Heights, Orchard Park, Sherwood Forest |

| Josh Morgan | Ward 7 | White Hills, Medway Heights, Masonville, Hyde Park |

| Steve Lehman | Ward 8 | Oakridge Park, Oakridge Acres |

| Anna Hopkins | Ward 9 | Byron, Lambeth, Woodhull, River Bend, Sharon Creek, Southwinds, Talbot |

| Paul Van Meerbergen | Ward 10 | Westmount, Rosecliffe Estates |

| Stephen Turner | Ward 11 | Cleardale, Southcrest Estates, Berkshire Village, Kensal Park, Manor Park |

| Elizabeth Peloza | Ward 12 | Glendale, Southdale, Lockwood Park, White Oak |

| Arielle Kayabaga | Ward 13 | Downtown London, Midtown, Blackfriars, Piccadilly/Adelaide, SoHo, Kensington, Woodfield, Oxford Park |

| Steve Hillier | Ward 14 | Glen Cairn Woods, Pond Mills, Wilton Grove, Glanworth |

Provincial ridings

The city includes four provincial ridings. In the provincial government, London is represented by New Democrats Terence Kernaghan (London North Centre), Teresa Armstrong (London—Fanshawe) and Peggy Sattler (London West), and Progressive Conservative Jeff Yurek (Elgin—Middlesex—London).[139]

Federal ridings

The London and surrounding area includes four federal ridings.[140] In the federal government, London is represented by Conservative Karen Vecchio (Elgin—Middlesex—London), Liberals Peter Fragiskatos (London North Centre) and Kate Young (London West), and NDP Lindsay Mathyssen (London—Fanshawe).[141]

Crime

Statistics from police indicate that total overall crimes in London have held steady between 2010 and 2016, at roughly 24,000 to 27,000 incidents per year.[142] The majority of incidents are property crimes, with violent crimes dropping markedly (up to about 20%) between 2012 and 2014 but rising again in 2015–2016. In July 2018, Police Deputy Chief Steve Williams was quoted as saying many crimes go unreported to police.[143]

The city has been home to several high-profile incidents over the years such as the Ontario Biker War and the London Conflict, it was also the location where most of the trial for the Shedden Massacre took place.

Research by Michael Andrew Arntfield, a police officer turned criminology professor, has determined that on a per-capita basis, London Ontario had more active serial killers than any locale in the world from 1959 to 1984.[144] Arntfield determined there were at least six serial killers active in London during this era. Some went unidentified, but known killers in London included Russell Maurice Johnson, Gerald Thomas Archer, and Christian Magee.[145]

On 6 June 2021 four members of a Canadian Muslim family, two women aged 74 and 44, a 46-year-old man and a 15-year-old girl were all killed by a pickup truck which jumped the curb and ran them over. The sole survivor was a 9-year-old boy. According to the London Police Service, they were deliberately targeted in anti-Islamic hate crime. Later on the same day, 20 year old Nathaniel Veltman was arrested in the parking lot of a nearby mall. He has been charged with four counts of first-degree murder and one count of attempted murder.[146][147]

Civic initiatives

The City of London initiatives in Old East London are helping to create a renewed sense of vigour in the East London Business District. Specific initiatives include the creation of the Old East Heritage Conservation District under Part V of the Ontario Heritage Act, special Building Code policies and Facade Restoration Programs.[148]

London is home to heritage properties representing a variety of architectural styles,[149] including Queen Anne, Art Deco, Modern, and Brutalist

Londoners have become protective of the trees in the city, protesting "unnecessary" removal of trees.[150] The City Council and tourist industry have created projects to replant trees throughout the city. As well, they have begun to erect metal trees of various colours in the downtown area, causing some controversy.[151]

Transportation

Road transportation

London is at the junction of Highway 401 that connects the city to Toronto and Windsor, and Highway 402 to Sarnia.[152][153] Also, Highway 403, which diverges from the 401 at nearby Woodstock, provides ready access to Brantford, Hamilton, and the Niagara Peninsula.[154] Many smaller two-lane highways also pass through or near London, including Kings Highways 2, 3, 4, 7 and 22. Some of these are no longer highways, as provincial downloading in the 1980s and 1990s put responsibility for most provincial highways on municipal governments.[155] Nevertheless, these roads continue to provide access from London to nearby communities and locations in much of Western Ontario, including Goderich, Port Stanley and Owen Sound. A 4.5 km long section of Highbury Ave., connecting the east end of London to Highway 401, consists of an controlled-access highway with 100 km/h speed limits.[156]

Since the 1970s, London has improved urban road alignments that eliminated "jogs" in established traffic patterns over 19th-century street misalignments. The lack of freeways directly through the city as well as the presence of two significant railways (each with attendant switching yards and few over/underpasses) are the primary causes of rush hour congestion, along with construction and heavy snow. Thus, traffic times can be significantly variable, although major traffic jams are rare.[157] Wellington Road between Commissioners Road E and Southdale Road E is London's busiest section of roadway, with more than 46,000 vehicles using the span on an average day[158] City council rejected early plans for the construction of a freeway, and instead accepted the Veterans Memorial Parkway to serve the east end.[159] Some Londoners have expressed concern the absence of a local freeway may hinder London's economic and population growth, while others have voiced concern such a freeway would destroy environmentally sensitive areas and contribute to London's suburban sprawl.[157] Road capacity improvements have been made to Veterans Memorial Parkway (formerly named Airport Road and Highway 100) in the industrialized east end.[160] However, the Parkway has received criticism for not being built as a proper highway; a study conducted in 2007 suggested upgrading it by replacing the intersections with interchanges.[161]

Public transit

In the late 19th century, and the early 20th century, an extensive network of streetcar routes served London.[162][163]

London's public transit system is run by the London Transit Commission, which has 44 bus routes throughout the city.[164] Although the city has lost ridership over the last few years, the commission is making concerted efforts to enhance services by implementing a five-year improvement plan. In 2015, an additional 17,000 hours of bus service was added throughout the city. In 2016, 11 new operators, 5 new buses, and another 17,000 hours of bus service were added to the network.[165] Bus service is currently the only mode of public transit available to the public in London, with no available rapid transit networks like those used in other Canadian cities. However, the city council approved a bus rapid transit (BRT) network, named Shift, in May 2016. The network will consist of two corridors serving each end of the city, and meeting at a central hub in the downtown. Construction is expected to begin in 2018, with the service fully operational by 2025.[166]

Cycling network

London has 330 km (205 mi) of cycling paths throughout the city, 91 km (59 mi) of which have been added since 2005.[167] In June 2016, London unveiled its first bike corrals, which replace parking for one vehicle with fourteen bicycle parking spaces, and fix-it stations, which provide cyclists with simple tools and a bicycle pump, throughout the city.[168] In September 2016, city council approved a new 15 year cycling master plan that will see the construction of an additional 470 km (292 mi) of cycling paths added to the existing network.[167][169]

Intercity transport

London is on the Canadian National Railway main line between Toronto and Chicago (with a secondary main line to Windsor) and the Canadian Pacific Railway main line between Toronto and Detroit.[170] Via Rail operates regional passenger service through London station as part of the Quebec City–Windsor Corridor, with connections to the United States.[171] Via Rail's London terminal is the fourth-busiest passenger terminal in Canada.[170]

London is also a destination for inter-city bus travellers. In 2009, London was the seventh-busiest Greyhound Canada terminal in terms of passengers,[172] At one point, service was available from London throughout southwestern Ontario and through to the American cities of Detroit, Michigan and Chicago, Illinois.

London International Airport (YXU) is the 12th busiest passenger airport in Canada and the 11th busiest airport in Canada by take-offs and landings.[170] It is served by airlines including Air Canada Express, and WestJet, and provides direct flights to both domestic and international destinations, including Toronto, Orlando, Ottawa, Winnipeg, Calgary, Cancún, Vancouver, Varadero, Punta Cana, Montego Bay, Santa Clara, and Holguin.[173]

Plans

The city of London is considering bus rapid transit (BRT) and/or high-occupancy vehicle lanes (HOV) to help it achieve its long-term transportation plan. Additional cycleways are planned for integration in road-widening projects, where there is need and sufficient space along routes. An expressway/freeway network is possible along the eastern and western ends of the city, from Highway 401 (and Highway 402 for the western route) past Oxford Street, potentially with another highway, joining the two in the city's north end.[157]

The city of London has assessed the entire length of the Veterans Memorial Parkway, identifying areas where interchanges can be constructed, grade separations can occur, and where cul-de-sacs can be placed. Upon completion, the Veterans Memorial Parkway would no longer be an expressway, but a freeway, for the majority of its length.[174]

Education

London public elementary and secondary schools are governed by four school boards – the Thames Valley District School Board, the London District Catholic School Board and the French first-language school boards (the Conseil scolaire Viamonde and the Conseil scolaire catholique Providence or CSC).[175] The CSC has a satellite office in London.[176]

There are also more than twenty private schools in the city.[175]

The city is home to two post-secondary institutions: the University of Western Ontario (UWO) and Fanshawe College, a college of applied arts and technology.[175] UWO, founded in 1878, has about 3,500 full-time faculty and staff members and almost 30,000 undergraduate and graduate students.[177] It placed tenth in the 2008 Maclean's magazine rankings of Canadian universities.[178] The Richard Ivey School of Business, part of UWO, was formed in 1922 and ranked among the best business schools in the country by the Financial Times in 2009.[179] UWO has three affiliated colleges: Brescia University College, founded in 1919 (Canada's only university-level women's college);[180] Huron University College, founded in 1863 (also the founding college of UWO) and King's University College, founded in 1954.[181][182] All three are liberal arts colleges with religious affiliations: Huron with the Anglican Church of Canada, King's and Brescia with the Roman Catholic Church.[183] London is also home to Lester B. Pearson School for the Arts one of few of its kind.

Fanshawe College has an enrollment of approximately 15,000 students, including 3,500 apprentices and over 500 international students from more than 30 countries.[184] It also has almost 40,000 students in part-time continuing education courses.[184] Fanshawe's Key Performance Indicators (KPI) have been over the provincial average for many years now, with increasing percentages year by year.[185]

The Ontario Institute of Audio Recording Technology (OIART), founded in 1983, offers recording studio experience for audio engineering students.[186]

Westervelt College is also in London. This private career college was founded in 1885 and offers several diploma programs.[187]

See also

- CFB London

- List of people from London, Ontario

- List of royal visits to London, Ontario

- List of tallest buildings in London, Ontario

- Asteroid 12310 Londontario, named for the city.

- Flag of London, Ontario

References

- "London (City) community profile". 2006 Census data. Statistics Canada. 13 March 2007. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- "London (Census metropolitan area) community profile". 2006 Census data. Statistics Canada. 13 March 2007. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population, City of London". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population, City of London". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- "London (City) community profile". 2016 Census data. Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- "Table 36-10-0468-01 Gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, by census metropolitan area (CMA) (x 1,000,000)". Statistics Canada. 27 January 2017. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- St-Denis, Guy (1985). Byron:Pioneer Days in Westminster Township. Crinklaw Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 0-919939-10-4.

- Max Braithwaite (1967). Canada: wonderland of surprises. Dodd, Mead. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016.

- Spelt, J (1972). Urban development in south-central Ontario. McClelland and Stewart.

- Adam, Graeme Mercer; Mulvany, Charles Pelham; Robinson, Christopher Blackett (1885). History of Toronto and County of York, Ontario: Containing an Outline of the History of the Dominion of Canada; a History of the City of Toronto and the County of York, with the Townships, Towns, General and Local Statistics; Biographical Sketches (Part II: The County of York). Vol. 1. C.B. Robinson. p. 9.

- Roosa, William B.; Deller, D. Brian (1982). "The Parkhill Complex and Eastern Great Lakes Paleo Indian" (PDF). Ontario Archaeology. 37: 3–15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- "Parkhill National Historic Site of Canada". Parks Canada. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "Lawson Site". Canada's Historic Places. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- "Lawson Site". Museum of Ontario Archaeology. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- Schmalz, Peter S. (1991). The Ojibwa of Southern Ontario. Toronto: University of Toronto Press|. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8020-6778-4.

- "City of London Land Acknowledgement | City of London". london.ca. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- Greg Curnoe, Deeds/Abstracts: The History of a London Lot (Brick Books, London Ontario,1995, ISBN 0-919626-78-5), pgs.41.

- "Missionary work Among The Ojebway Indians chap. 14". PROJECT GUTENBERG.

- City of London, Ontario, Canada. The Pioneer Period and the London of To-Day (2nd ed.). October 1900. p. 20.

- "Upper Canada Land Surrenders". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- "Document 8: London Township Treaty (1796)". 10 March 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- "The beginnings". City of London. 2009. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Parks Canada Agency, Government of Canada (7 December 2016). "Battle Hill National Historic Site". pc.gc.ca. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Event Highlights for the City of London 1793–1843". City of London. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- "Event Highlights for the City of London 1844–1894". City of London. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Adams, Bill (2002). The History of the London Fire Department of heroes, helmets and hoses (1st ed.). London Fire Department. p. 13. ISBN 0-9732159-0-9.

- Lutman, John (1977). The Historic Heart of London. Corporation of the City of London. p. 6.

- Smith, Wm. H. (1846). Smith's Canadian Gazetteer – Statistical and General Information Respecting all parts of The Upper Province, or Canada West. Toronto: H. & W. Rowsell. p. 100. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Ontario White Sulphur Springs". The London and Middlesex Historical Society. Archived from the original on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- McEvoy, H (1869). The Province of Ontario Gazetteer and Directory. Toronto: Robertson & Cook. pp. 269–271. ISBN 0665094124.

- not stated (1889). History of the County of Middlesex, Canada. London: W.A. & C.L. Goodspeed. p. 294. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017.

- "RootsWeb.com Home Page". freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- Richard Preston 'Canada's RMC: A History of the Royal Military College of Canada' published by the RMC Club by U of Toronto Press.

- Moore, Avery (19 December 2013). "Blackfriars Bridge Open To Pedestrians". Blackburn News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Stott, Gregory (1999). "Four". The Maintenance of Suburban Autonomy: The Story of the Village of Petersville-London West, Ontario, 1874–1897 (MA thesis). University of Western Ontario.

- "Item 9b" (PDF). London Advisory Committee on heritage. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- Wilson, Robert. "London East". London and Middlesex Historical Society. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "Broughdale Community Association". BCA. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- Ivor F. Goodson and Ian R. Dowbiggin, "Vocational education and school reform: the case of the London (Canada) Technical School, 1900-1930" History of Education Review (1991) 20#1: 39–60.

- "London, Ontario". Department of National Defence. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "History of London – 1977 to 2000". City of London. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Martin, Chip (29 December 2007). "Did Annexation Work?". Special Report. London Free Press.

- "New Directions in Urban Planning". Urban League of London. Archived from the original on 3 December 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "Environmentally Significant Areas". Urban League of London. 2006. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for census metropolitan areas, 2006 and 2001 censuses: 100% data". Statistics Canada. 19 December 2008. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- "Population and dwelling counts, for urban areas, 2006 and 2001 censuses: 100% data". Statistics Canada. 5 November 2008. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- "Event Highlights for the City of London 1930–1949". City of London. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "Historical Flood-Related Events". Environment Canada. 18 February 2009. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- "The London Building Disaster". The Canadian Architect and Builder, Vol. XI, Issue 1. January 1898. p. 2. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Event Highlights for the City of London 1950–1959". City of London. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "Event Highlights for the City of London 1980–1989". City of London. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- LeBel, Jacquelyn; Bogdan, Sawyer; Westoll, Nick (11 December 2020). "2 dead, 4 in hospital following building collapse in southwest London, Ont". Global News. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- "2 dead, 4 in hospital after partial building collapse at London, Ont., construction site". CBC. 11 December 2020. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- Juha, Jonathan (26 April 2021). "Labour ministry completes on-site probe of fatal construction collapse". Simcoe Reformer. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- Juha, Jonathan (31 August 2021). "Families of workers hurt in construction collapse file $2M lawsuit". The London Free Press. Archived from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- "Man suspected of killing Canadian Muslim family was motivated by hate -police". Reuters. 7 June 2021.

- Gillies, Rob (7 June 2021). "Canadian police say family run down targeted as Muslims". The Washington Post. AP. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- Juha, Jonathan (8 June 2021). "Police remain at accused mass killer's downtown London home". The London Free Press. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- "Ontario". Historica-Dominion. 2009. Archived from the original on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "Your Guide to London's Major Public Parks & Gardens". City of London. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "Fanshawe Dam". Upper Thames River Conservation Authority. Archived from the original on 19 August 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "London INT'L Airport, Ontario". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. 25 September 2013. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Environment and Climate Change (16 December 2010). "Environment and Climate Change Canada – Weather and Meteorology – Canada's Top Ten Weather Stories for 2010 – Runner-Up stories". ec.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Daniszewski, Hank (7 December 2010). "It's one for the history books". London Free Press. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- "Long Term Climate Extremes for London Area (Virutal Station ID: VSON137)". Daily climate records (LTCE). Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- "August 1918". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "London INT'L Airport". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- Censuses 1871–1931 (PDF). Canada Yearbook 1932. Statistics Canada. 31 March 2008. p. 103. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2014.

- Census 1941–1951 (PDF). Canada Yearbook 1955. 31 March 2008. p. 145. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2013.

- Census 1961 (PDF). Canada Yearbook 1967. 31 March 2008. p. 189. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2014.

- Censuses 1966, 1971 (PDF). Canada Year Book 1974. 31 March 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2014.

- Censuses 1981, 1986 (PDF). Canada Year Book 1988. 31 March 2008. p. 192. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2014.

- "Canada: Ontario". City Population. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012.

- "2006 Community Profiles: London". Statistics Canada. 6 December 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions (municipalities), Ontario". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- Multiple ethnic/cultural origins can be reported

- "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - London, City (CY) [Census subdivision], Ontario". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022.

- "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - London, City (CY) [Census subdivision], Ontario". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022.

- "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - London, City (CY) [Census subdivision], Ontario". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022.

- "Economic Analysis of Ontario" (PDF). Central 1. 9 (1). March 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "London Labour Market Monitor". Service Canada. January 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- "LEDC – London Economic Development Corporation". LEDC – London Economic Development Corporation. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- "LEDC – London Economic Development Corporation". LEDC – London Economic Development Corporation. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- "LEDC – London Economic Development Corporation". LEDC – London Economic Development Corporation. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- nurun.com (13 December 2015). "The Cube: London's newest digital hothouse". The London Free Press. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- "LRH Honoured with ACO Award". The London Roundhouse Project. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- "Paystone bags another C$30m". 26 July 2021.

- "Corporate Information: Company Overview". London Life. 2006. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- Granger, Alix; Daly, Eric W. (7 February 2006). Canada Trust. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "Our History". Archived from the original on 31 July 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "Introducing the New Libro Credit Union". Libro Credit Union. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "General Dynamics Awarded $5 Million Contract to Perform Engineering Studies in Support of Mobile Gun System" (Press release). General Dynamics Land Systems. 22 October 2004. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- De Bono, Norman (30 September 2015). "Union asks NDP to keep Saudi armoured vehicles deal 'under wraps,' fearing 'significant' job losses". Postmedia Network. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- DeBono, Norman (16 September 2011). "Ontario Ford plant closure brings tears". Toronto Sun. Québecor Média. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "Jobs, jobs, jobs: Amazon hiring 2,000 workers for local fulfillment centre".

- "The Transformation of Galleria London – Reurbanist". reurbanist.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- "Public library the new home for CBC's digital, radio programming in London, Ont". CBC News. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- Dubinski, Kate (1 December 2009). "London lands freight centre". London Free Press. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ago, Christopher Lombardo 4 days (31 August 2022). "London, Ontario is making an offer filmmakers can't refuse". strategy. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- "Amazing Race, awesome city: Reality show set to leg it through London". lfpress. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- "Apple TV series filming Wednesday in downtown London, Ont". London. 24 August 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- "Pride London Festival". Pride London Festival. Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- "Ribfest". Family Shows Canada. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- "About Sunfest". Sunfest. Archived from the original on 28 July 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- "Call the Office closes indefinitely, adding to city's live music industry woes". lfpress. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- "94.9 CHRW – London Music Archive". chrwradio.com. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016.

- Taccone, Amanda (8 November 2021). "London, Ont. is Canada's first UNESCO City of Music". CTV News London. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- "105". IATSE Labor Union, representing the technicians, artisans and craftpersons in the entertainment industry. 21 May 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- "Museum of Ontario Archaeology". University of Western Ontario. Archived from the original on 14 July 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "Eldon House Historical Plaque". Archives of Ontario. 2005. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- "Sir Frederick G. Banting Square". Canadian Diabetes Association. Archived from the original on 8 April 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- "History of The Palace". The Palace Theatre. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Our History". Original Kids Theatre Company. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Search – Directory of Special Collections of Research Value in Canadian Libraries". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- Gordon, Julie (15 April 2021). "Canadian home sales, prices surge to new record in March". CTVNews. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- "LSTAR Home Sales Remain Steady | London St. Thomas Association of Realtors". lstar.ca. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- "Home market cooling? Average local sale price dips after 13-month streak". lfpress. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- Khan, Mikael; Bilyk, Olga; Ackman, Matthew (9 April 2021). "Update on housing market imbalances and household indebtedness". bankofcanada.ca. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- "Cost of Living in London". numbeo.com. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- "Major Parks and Gardens". london.ca. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- "Thames Valley Parkway". london.ca. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- "Facilities". University of Western Ontario. 2009. Archived from the original on 26 September 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- "Lethbridge Runners cross the finish line first at the 2008 CCAA Cross Country Running Open". CCAA. June 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "Alberta Runners Top 2010 CCAA Cross Country Running Nationals". CCAA. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- "Western Fair Raceway". Western Fair Entertainment Centre. 2006. Archived from the original on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- McLarty, Butch (1 April 2014). "April Baseball at Historic Labatt Park". London Free Press. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "Parks and Recreation Newsletter" (PDF). City of London. June 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2009.