Hurricane Diane

Hurricane Diane was the first Atlantic hurricane to cause more than an estimated $1 billion in damage (in 1955 dollars, which would be $10,115,527,950 today[1]), including direct costs and the loss of business and personal revenue.[nb 1] It formed on August 7 from a tropical wave between the Lesser Antilles and Cape Verde. Diane initially moved west-northwestward with little change in its intensity, but began to strengthen rapidly after turning to the north-northeast. On August 12, the hurricane reached peak sustained winds of 105 mph (165 km/h), making it a Category 2 hurricane. Gradually weakening after veering back west, Diane made landfall near Wilmington, North Carolina, as a strong tropical storm on August 17, just five days after Hurricane Connie struck near the same area. Diane weakened further after moving inland, at which point the United States Weather Bureau noted a decreased threat of further destruction. The storm turned to the northeast, and warm waters from the Atlantic Ocean helped produce record rainfall across the northeastern United States. On August 19, Diane emerged into the Atlantic Ocean southeast of New York City, becoming extratropical two days later and completely dissipating by August 23.

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Weather map of Hurricane Diane on August 19 as it neared North Carolina | |

| Formed | August 7, 1955 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 23, 1955 |

| (Extratropical after August 21) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 105 mph (165 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 969 mbar (hPa); 28.61 inHg |

| Fatalities | ≥184 |

| Damage | $831.7 million (1955 USD) |

| Areas affected | North Carolina, Mid-Atlantic states, New England |

| Part of the 1955 Atlantic hurricane season | |

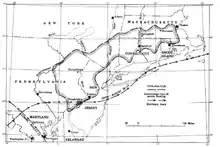

The first area affected by Diane was North Carolina, which suffered coastal flooding but little wind and rain damage. After the storm weakened in Virginia, it maintained an area of moisture that resulted in heavy rainfall after interacting with the Blue Ridge Mountains, a process known as orographic lift. Flooding affected roads and low-lying areas along the Potomac River. The northernmost portion of Delaware also saw freshwater flooding, although to a much lesser extent than adjacent states. Diane produced heavy rainfall in eastern Pennsylvania, causing the worst floods on record there, largely in the Poconos and along the Delaware River. Rushing waters demolished about 150 road and rail bridges and breached or destroyed 30 dams. The swollen Brodhead Creek virtually submerged a summer camp, killing 37 people. Throughout Pennsylvania, the disaster killed 101 people and caused an estimated $70 million in damage (1955 USD). Additional flooding spread through the northwest portion of neighboring New Jersey, forcing hundreds of people to evacuate and destroying several bridges, including one built in 1831. Storm damage was evident but less significant in southeastern New York.

Damage from Diane was heaviest in Connecticut, where rainfall peaked at 16.86 in (428 mm) near Torrington. The storm produced the state's largest flood on record, which effectively split the state into two by destroying bridges and cutting communications. All major streams and valleys were flooded, and 30 stream gauges reported their highest levels on record. The Connecticut River at Hartford reached a water level of 30.6 ft (9.3 m), the third highest on record there. The flooding destroyed a large section of downtown Winsted, much of which was never rebuilt. Record-high tides and flooded rivers heavily damaged Woonsocket, Rhode Island. In Massachusetts, flood water levels surpassed those during the 1938 Long Island hurricane, breaching multiple dams and inundating adjacent towns and roads. Throughout New England, 206 dams were damaged or destroyed, and about 7,000 people were injured. Nationwide, Diane killed at least 184 people and destroyed 813 houses, with another 14,000 homes heavily damaged. In the hurricane's wake, eight states were declared federal disaster areas, and the name Diane was retired.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Hurricane Diane originated in a tropical wave first observed as a tropical depression on August 7 between the Lesser Antilles and Cape Verde.[2] The system moved generally to the west-northwest, intensifying into a tropical storm on August 9.[3] By the time the Weather Bureau first classified the storm on August 10, Diane was south of the Bermuda high, a semi-permanent ridge in the jet stream just east of Nova Scotia. Ships in the region of the storm reported winds of 45 mph (72 km/h). During the next day, the Hurricane Hunters reported no increase in strength, and Diane initially remained disorganized.[2] The storm interacted with Hurricane Connie to its northwest in a process known as the Fujiwhara effect, in which Diane turned toward the north. Quick intensification ensued, potentially due to interaction with a cold-core low that increased atmospheric instability.[2] On August 12, the storm rapidly intensified into a hurricane.[3] The intensification was so quick that a ship southeast of the center believed Diane was undergoing a loop due to a steady drop in barometric pressure, despite moving away from the hurricane.[2]

At its peak, Diane developed a well-defined eye about 30 mi (48 km) in diameter, described by reconnaissance aircraft as taking the shape of an "inverted teacup". The strongest winds were located in the northeast quadrant, where there was a secondary pressure minimum located 62 mi (100 km) northeast of the eye.[2] After moving to the north for about a day, Diane resumed its westward motion on August 13, after Hurricane Connie to the northwest had weakened. That day, Diane reached its lowest pressure of 969 mbar (28.6 inHg),[2] and peak winds of 105 mph (170 km/h); originally the hurricane was analyzed to reach peak winds of 120 mph (195 km/h), although the large size and slow forward speed suggested the lower winds. It maintained its peak winds for about 12 hours,[4] after which it weakened due to cooler air in the region. By August 15, the eye had become poorly defined, and winds steadily weakened. As it approached land, its center deteriorated, with minimal precipitation near the center; the eye was observed on a radar installed in July 1955. On August 17, Diane made landfall on the coast of North Carolina near Wilmington.[2] Pressure at landfall was estimated at 986 millibars (29.1 inHg), accompanied by winds just under hurricane intensity.[5] Diane struck the state only five days after Hurricane Connie struck the same general area.[3]

Diane quickly weakened as a tropical storm over the mountainous terrain of central North Carolina.[4] The associated area of precipitation expanded and spread away from the center to the north and northeast.[6] The weakening system turned to the north and recurved toward the northeast through Virginia after a ridge built in from the west.[7] It did not interact much with the non-tropical westerlies, and as a result it remained a distinct tropical cyclone over land. Convection redeveloped as the storm approached the Atlantic coast once again.[6] Diane passed through the Mid-Atlantic states, exiting New Jersey on August 19 into the Atlantic Ocean southeast of New York City. Paralleling the southern coast of New England, the storm later accelerated east-northeastward, becoming extratropical on August 21. Passing south and east of Newfoundland, the remnants of Diane accelerated and restrengthened slightly while moving to the northeast. Late on August 23, the storm dissipated between Greenland and Iceland.[4]

Preparations and background

Late on August 14, more than two days before Diane made landfall, the United States Weather Bureau issued a hurricane alert from Georgia through North Carolina. On August 15, the agency issued a hurricane warning from Brunswick, Georgia to Wilmington, North Carolina, although the warning was later extended to the south and north to Fernandina, Florida and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, respectively. The agency also issued storm warnings southward to Saint Augustine, Florida and northward to Atlantic City, New Jersey, including the Chesapeake and Delaware bays. Throughout the warned region, small ships were advised to remain at port.[8] Before Diane made landfall, the North Carolina National Guard assisted in evacuating people near the Pamlico River, and 700 residents left their homes near New Bern; thousands of tourists also evacuated.[9] The threat of the hurricane forced the planned retirement ceremony for Admiral Robert Carney to be transferred from an aircraft carrier in Norfolk, Virginia to an academy dormitory.[10] All aircraft at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point were flown to safer locations further inland.[11]

All hurricane warnings were dropped after Diane moved inland.[8] Forecasters downplayed the threat of Diane after it weakened over Virginia;[12] the Weather Bureau agreed they did not foresee the extent of the rain that would occur, instead calling for just "some local flooding".[13] The agency later admitted they "goofed" in downplaying the storm's destructive potential after weakening,[14] noting their lack of experience with extreme rainfall events.[15] Once the storm moved ashore, the Weather Bureau transferred official forecasting duties to regional offices, and local newspapers also issued their own forecasts.[14] The Springfield Daily News in Massachusetts noted that "moderate rains [were] possible" in its daily weather forecast ahead of the storm.[16] Still, flood warnings were issued, with stream flooding forecasts of over 12 hours in advance. Along smaller rivers, including the Lehigh, Schuylkill, and Farmington, forecasts were issued every few hours.[8]

In the summer of 1955, the eastern United States experienced generally hot and dry weather, leading to drought conditions and decreased water levels.[17] When Hurricane Connie struck, its rainfall moistened the soil and heightened creeks throughout the Mid-Atlantic and New England.[8] Hurricane Diane struck North Carolina just five days later and affected the same general area.[17] After floods in 1936, the United States federal government enacted plans to prevent future devastating floods, although they made no progress by the time Connie and Diane struck in 1955.[18] Along the Delaware River in the 1930s, state legislatures in New Jersey and Pennsylvania had established a commission that worked to clean up polluted water, but the legislators and commission blocked federal help, comparing it to European socialism; this was in contrast to the federally funded Tennessee Valley Authority, which mitigated flooding along the Tennessee River.[19]

Impact

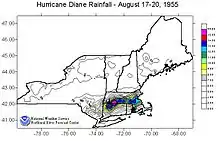

Hurricane Diane's path over the eastern United States brought heavy rainfall, fueled by unusually moist air resulting from abnormally high sea surface temperatures.[20] The worst flooding was in eastern Pennsylvania, northern New Jersey, southeastern New York, and southern New England.[8] Of the 287 stream gauges in the region, 129 reported record levels during the course of the event. Many streams reported discharge rates of more than double the previous records.[17] Most of the flooding occurred along small rivers that rose to flood stage within hours, largely impacting populated areas;[8] there were around 30 million people in the region affected by the floods.[17] Overall, 813 houses were destroyed,[21] with 14,000 heavily damaged.[22] The storms damage caused over 35,000 families to re locate.[23] The floods also severed infrastructure and affected several summer camps.[8] Damage to public utilities was estimated at $79 million. Flooding in rural areas resulted in landslides in the mountains, while destroyed crops cost an estimated $7 million. Hundreds of miles of roads and bridges were also destroyed, accounting for $82 million in damage.[21] Damage from Diane's winds were generally minor.[17] The hurricane caused $831.7 million in damage,[24] of which $600 million was in New England,[2] making it the costliest hurricane in American history at the time.[21] Taking into account indirect losses, such as loss of wages and business earnings, Diane was described as "the first billion dollar hurricane."[2] This contributed to 1955 being the costliest Atlantic hurricane season on record at the time.[2] Overall, there were at least 184 deaths, potentially as many as 200.[25]

Carolinas

The strongest sustained winds associated with Diane's landfall in North Carolina reached 50 mph (80 km/h) in Hatteras, with gusts to 74 mph (119 km/h) in Wilmington. Any hurricane-force gusts were likely very sporadic and isolated in nature. Tides ran 6 to 8 ft (1.8 to 2.4 m) above normal near Wilmington, and waves 12 ft (3.7 m) in height struck the coast. The resultant storm surge damaged beach houses, flooded coastal roads, and destroyed seawalls damaged by Hurricane Connie a few days prior.[2][9] The center of the storm passed over Wilmington without much of a decrease in winds, suggesting the eye had largely dissipated in the weakening tropical cyclone. Little precipitation fell in and around the city,[2] though precipitation was more substantial elsewhere in the state, peaking at 7.04 in (179 mm) in New Bern. At Oakway in neighboring South Carolina, rainfall amounted to 2.39 in (61 mm).[26]

Mid-Atlantic

After Diane crossed into Virginia, it dropped heavy rainfall of over 10 in (250 mm) in 24 hours in the Blue Ridge Mountains,[8] peaking at 11.72 in (298 mm) in Big Meadows.[27] There, the rains were enhanced by moist air rising over the mountain peaks and condensing, a process known as orographic lift.[8] Rainfall of over 3 in (76 mm) occurred throughout Virginia, as well as into the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia,[28] where 5.71 in (145 mm) was reported at Stony River Reservoir. Similar precipitation amounts fell through Delaware, including 3.27 in (83 mm) at the National Arboretum in Washington, D.C.[27] Rivers across the region rose above flood stage, including the James River which crested at 30.4 ft (9.3 m) in Columbia, Virginia, which was 14.6 ft (4.5 m) above flood stage.[8] High amounts of rainfall accrued in eastern Pennsylvania, peaking at 11.11 in (282 mm) in Pecks Pond in the northeast portion of the state.[27][28] As with Virginia, the heaviest rainfall occurred due to orographic lift near a mountain.[8] In neighboring New Jersey, the highest precipitation was 8.10 in (206 mm) near Sussex. Rainfall in New York peaked at 9.05 in (230 mm) in Lake Mohonk.[27]

In Virginia, severe flooding occurred near Richmond and along the Blue Ridge Mountains. Near the coast, Diane damaged large areas of farmlands due to slow-moving floods. In the state, 21 gauges reported their highest levels on record.[17] High levels along the Potomac River flooded low-lying portions of Virginia and Washington, D.C.[29] Wind gusts reached 62 mph (100 km/h) in Roanoke.[12] In the state, flooding covered several roads, prompting closures.[30] Due to the flat terrain, flooding in Delaware was described by the United States Geological Survey as "comparably mild". Flooding along the Brandywine Creek was at least the fifth highest in 45 years.[17] Flooding was worst in the northernmost portion of the state.[31]

Flooding began in many streams in eastern Pennsylvania on August 18. The Delaware River crested at over 40 ft (12 m) in Easton, which was 4 ft (1.2 m) above the previous record set in 1903. In Allentown, the Lehigh River crested at 23.4 ft (7.1 m), surpassing the previous record of 21.7 ft (6.6 m) set in 1942.[8] The floods were the worst in record across eastern portions of the state, notably in the Poconos and along all tributaries of the Delaware River from Honesdale to Philadelphia. Lake Wallenpaupack and other reservoirs mitigated flooding. Floods destroyed 17 bridges and 55 mi (89 km) of track along the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad, which is the primary rail line in northeastern Pennsylvania.[17] Damage to the line totaled several million dollars, and overall railroad damage in the state totaled $16 million.[21] Hundreds of cars were damaged in the region.[17] Damage extended into Philadelphia due to flooding along the Schuylkill River, but the damage was minor.[21] In the small village of Upper Black Eddy, hundreds of people became homeless, and the post office was washed away.[32] Statewide, the floods destroyed or breached 30 dams, and destroyed about 150 road of rail bridges.[31] Flooding left home and factory damage in the Allentown area.[12] In the Poconos in Pennsylvania, the Brodhead Creek nearly destroyed a camp,[8] killing 37 people, mostly children.[17] Many people at the camp fled to a lodge that was ultimately destroyed.[12] The Brodhead Creek also washed out a bridge along U.S. Route 209 between Stroudsburg and East Stroudsburg, flooding both cities.[17] There were about 75 deaths in the area,[8] and another 10 deaths occurred in Greentown due to flooding along the Lackawaxen River.[21] Overall, there were 101 deaths in the state,[17] and damage totaled at least $70 million.[21]

In New Jersey, flooding largely occurred north of Trenton and west of Perth Amboy;[17] rainfall in the southern two–thirds of the state was less than 3 in (76 mm).[12] The three major rivers in the area - the Delaware, Passaic, and Raritan - had severe flooding, and damage was widespread.[17] When the Millstone River flooded, two teenagers drowned while canoeing, and a police officer drowned while attempting to rescue them. About 200 families were evacuated in Oakland along the Ramapo River.[12] Damage in the state was heaviest along the Delaware from Port Jervis, New York to Trenton, where flooding inundated adjacent towns. Between the two towns, all but two bridges were damaged, including four that were destroyed.[17] About 500 children had to be rescued from camps on three islands in the Delaware River; they were airlifted to a high school in Frenchtown. In that city, about 200 people were forced to evacuate their houses along the water.[32] In Trenton, workers used sandbags to prevent flooding from affecting government buildings.[12] Flooding destroyed the Portland–Columbia Pedestrian Bridge, first constructed in 1831, after most of it was submerged. The center of the Northampton Street Bridge between Easton, Pennsylvania and Phillipsburg, New Jersey collapsed.[17] A dam near Branchville collapsed, flooding the town and causing heavy damage.[12][21] About 200 homes were damaged or destroyed in Lambertville.[12] Statewide, 93 homes were destroyed. Damage was estimated at $27.5 million.[21]

Flash floods occurred in mountainous regions of southeastern New York, including Port Jervis along the Delaware River. Wappinger Creek flooded to cause heavy damage. Most streams in the Rondout Creek basin left damage due to fast-moving waters,[17] including heavy damage near Ellenville. Damage in New York was largely limited to an area between Port Jervis and Poughkeepsie. Several bridges were destroyed along the Bash Bish Brook, and portions of U.S. Route 209 were flooded. Damage totaled $16.2 million, and there was one death in the state.[21]

New England

Diane produced heavy rainfall after recurving inland, setting rainfall records in several areas. Windsor Locks, Connecticut reported 12.05 in (306 mm) in a 23‑hour period;[2] the station's total, located near Hartford, was 5.32 in (135 mm) higher than the 24‑hour rainfall record in Hartford.[8] Some locations along the Housatonic River experienced 0.75 in (19 mm) per hour over 24 hours.[31] The highest total in the state was 16.86 in (428 mm) at a station near Torrington.[33] This is the highest rainfall on record in the state.[34] The highest rainfall in the United States related to the storm was 19.75 in (502 mm) in Westfield, Massachusetts,[28] which was also the wettest known storm in the state's history as well as throughout New England.[34] Other statewide rainfall maxima in New England included 8.45 in (215 mm) in Greenville, Rhode Island, 4.34 in (110 mm) in Essex Junction, Vermont, 3.31 in (84 mm) in Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire, and 0.62 in (16 mm) at Long Falls Dam in Maine.[33] Throughout New England, 206 dams were damaged or destroyed,[17] mostly in the region south of Worcester, Massachusetts.[35] About 7,000 people were injured throughout New England, most of whom in Connecticut.[21]

Damage was greatest in Connecticut, where floods affected about two-thirds of the state.[17] It was the largest flood on record in the state's history.[31] All major streams and valleys were flooded during the storm, including hundreds of tributaries, and 30 gauges in the state reported the highest level on record.[17] The Connecticut River at Hartford reached the third-highest level on record at the time, cresting at 30.6 ft (9.3 m), or 14.6 ft (4.5 m) above flood stage.[8] Although there was rural damage, the city of Hartford was spared from flooding due to previously constructed dykes.[21] The Naugatuck River had significant flooding that damaged or destroyed every bridge across it and did extensive damage in Ansonia. In Waterbury, the river washed buildings and railroad girders into a bridge.[17] In the city, 30 people were killed, including 26 in 13 houses that were washed away in one block.[36] The Quinebaug River flooded the city of Putnam at the same time that a major fire originated at a magnesium plant.[17][37] Much of the commercial district of Winsted was destroyed by the Mad River, which reached 10 ft (3.0 m) deep; the floods destroyed most buildings on the south side of the town's Main Street, and carried away several cars from a car dealership. The local newspaper reported that 95% of businesses were destroyed or severely damaged in Winsted.[36] High rivers destroyed historical sites and buildings,[17] and statewide Diane destroyed 563 houses.[21] There were 77 deaths in the state and $350 million in damage.[35] Most of the damage in the state was industrial or commercial damage.[21]

In Rhode Island, flooding was worst in the northern portion of the state, mostly along the Blackstone River,[17] which expanded to a width of about 1 mi (1.6 km).[12] The Horseshoe Dam was washed out, causing heavy damage in Woonsocket.[17] There, about 6,000 of its 50,000 residents were left unemployed.[37] Record high tides were also reported. In Rhode Island, damage was estimated at $21 million, mostly in Woonsocket, and there were three deaths.[31]

Much of southern Massachusetts, from its border with New York toward Worcester and to the ocean, experienced flooding. Most streams in western Massachusetts overflowed their banks, and in southeastern Massachusetts, which is largely flat terrain, streams flooded large areas along their channels; these streams moved slowly, while other areas in New England sustained damage due to the fast-moving nature of the floods. Record flooding was reported along 24 stream gauges in the state, including ones that surpassed the peak set by the 1938 New England hurricane.[17] Both the Charles and Neponset rivers were among those that flooded.[38] About 40% of the city of Worcester was flooded during Diane,[12] and in Russell, the state police forced many residents to evacuate.[16] In Weymouth, the floods were considered at least a 1 in 50 year event.[38] The Little River in Buffumville, Massachusetts had a peak discharge of 8,340 ft³/s (236 m³/s), which was 6.2 times greater than the previous peak and 28.5 times the average annual flooding. Flooded rivers breached run-of-the-river dams and covered nearby roadways, although dams with reservoirs resulted in less flooding. Nearly all dams along the French River were severely damaged or destroyed.[17] One failed dam in West Auburn washed out a portion of U.S. Route 20, and the same route was washed out near Charlton. An overflown brook also damaged the Massachusetts Turnpike.[21] A train on the Boston and Albany Railroad line plunged into a washed out portion along the Westfield River.[17] Along the same river, floods destroyed roads and tobacco farms.[21] In the state, 97 houses were destroyed.[21] Damage in Massachusetts was second worst of the affected states,[17] totaling $110 million;[21] the damage was largely due to flooded basements.[38] There were 12 deaths in the state.[21]

Aftermath

In Diane's immediate aftermath, one of the first priorities in response was to distribute adequate inoculations for typhoid amongst the widespread areas left without clean drinking water. The United States Army assisted in search and rescue operations using helicopters.[39] After the floods of Hurricane Diane, more than 100,000 people fled to shelter or away from their houses. The American Red Cross quickly provided aid to the affected residents,[12] using churches and public buildings to house homeless people.[40] In the two weeks after the storm, Americans donated about $10 million to the Red Cross.[41] The countries of Great Britain, Netherlands, Australia, Canada, France, Austria, and Venezuela offered aid to help the flood victims, sending emergency supplies.[42] Additional flooding affected New England in September and October 1955, although neither was as major as those caused by Hurricane Diane.[17] Following Diane, hundreds of companies affected by the flooding installed waterproof doors and windows to preempt similar disasters in the future.[43]

President Dwight Eisenhower declared eight states as disaster areas, making them eligible for federal aid.[44] The Small Business Administration opened 18 temporary offices in the eastern United States for people to take out disaster loan applications.[45] In the months after the storm, both the United States federal government and the American Red Cross had difficulty raising enough funds for the storm victims; collectively, the Red Cross, the Small Business Administration, and Farmers Home Administration raised $37 million, which was less than 8% of Diane's damage total. Throughout 1955, the Red Cross assisted about 10,000 families in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states; some of the families received aid to move to a new house not in a flood zone. The Small Business Administration provided about 1,600 loans, totaling $25 million, for small businesses.[46] Senator Herbert H. Lehman proposed a $12 billion federal flood insurance program.[47] In 1956, the United States Congress passed the Federal Flood Insurance Act, but the program was not enacted due to lack of funding.[48] A nationwide flood program was not enacted until the passage of the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968.[49] After the floods from Diane, the American federal government provided funding for the Army Corps of Engineers to construct dams and reservoirs throughout New England to mitigate future flooding. In about 14 years, the Corps built 29 dams in Connecticut alone at the cost of $70 million, including three along the Connecticut River.[40] The federal government restored plans from the 1930s to build dams along the Delaware River, one of which along Tocks Island. A controversy arose there due to the 40 mi (64 km) long reservoir the dam would have created, causing 600 families to be displaced. The project was canceled in 1975, and the acquired lands became the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area.[50]

In Pennsylvania, washed-out rail lines prevented operation along the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad for several weeks,[17] and lines reopened after about two months.[21] The expense of reopening, and the loss of being closed, led to the railroad merging with the Erie Railroad to become the Erie Lackawanna Railway in 1960.[51] One stranded train along the line prompted a helicopter to rescue 235 people. Flooding along the Lehigh River destroyed 15 industrial plants, which left more than 15,000 people near Allentown, Pennsylvania without work temporarily. The mayor of Scranton declared a state of emergency due to the floods, ordering all businesses to close. United States Army soldiers provided water to residents after the town lost its water supply. Elsewhere, the Pennsylvania National Guard was on duty on streets in damaged towns,[12] including 50 to prevent looting in Upper Black Eddy, which was one of the hardest hit towns.[32] Helicopters assisted in discovering bodies at Camp Davis, where many deaths occurred during the storm. Statewide, thousands of people were left homeless.[30] In Stroudsburg, there was a food shortage, and officials enacted a curfew, after reports of looting.[52] In the same city, water was shipped in milk cartons to the flood victims, which later inspired a Federal Civil Defense Administration proposal to use water packaged in milk containers in the event of a nuclear attack.[53] The state government implemented a tax on cigarettes to help pay for storm damage, which lasted for about two years;[54] this was partially due to a lack of significant funding from the federal government.[55] Pennsylvania also enacted an increase in the gasoline tax that was later made permanent to pay for the Interstate Highway System.[56] The two taxes, each an increase of 1 penny, totaled $71 million, a part of which was set aside for future disasters.[57] The experience of the storm's aftermath provided the basis for the aftermath for Hurricane Agnes in 1972.[55] In New Jersey, Governor Robert B. Meyner declared the floods as at the time the state's worst natural disaster.[12]

After the Naugatuck River flood in Connecticut cut off communications and bridges, the state was effectively cut in two.[17] The state's National Guard used helicopters to rescue people. Governor Abraham A. Ribicoff visited areas affected by the flooding, due to the damage, Connecticut was declared a federal disaster area on August 20.[40][58] The declaration allocated $25 million in assistance to the state. Governor Ribicoff requested $34 million in funds to rebuild and produce future flood mitigation projects; the state's funding was paid by a combination of bonds and tax increases.[36] Including subsequent storms, the 1955 floods cumulatively killed 91 people and left 1,100 families homeless. Flooding occurred in 67 towns, resulting in damage to 20,000 families. About 86,000 people were left unemployed after the floods.[40] In Winsted, the buildings that were washed away along the south side of Main Street were never rebuilt.[36]

Massachusetts Governor Christian Herter also issued a state of emergency, due to the widespread flooding damage. As a result, the state's National Guard and the Army Corps assisted in cleanup, and most roads took three weeks to clear.[16] Residents in areas affected by Diane's flooding were advised to boil water and not to use gas cooking equipment.[30] Diane's historic rainfall resulted in the wettest month on record in Boston with a total of 17 in (430 mm), a record that stands as of 2010;[59] Boston's 24‑hour total of 8.4 in (210 mm) remained the highest daily total as of 1996.[60] Following Diane's floods, cities in Massachusetts enlarged culverts and improved draining systems, as well as constructing weirs; these systems helped mitigate against future flooding.[38]

The name Diane was retired from the Atlantic hurricane naming list.[61] Due to the damage from hurricanes in 1954 and 1955, including Diane, public outcry over storm damage led to the creation of the National Hurricane Center in 1956.[62] Using a monetary deflator in 2010 United States dollars, the damage from Diane would be about $7.4 billion, which would have been the 17th highest in the United States. Accounting for inflation, changes in personal wealth, and population changes, it is estimated Diane would have caused $18 billion in damage in 2010, or the 15th highest for a United States hurricane.[63]

See also

- List of wettest tropical cyclones in Massachusetts

- List of North Carolina hurricanes (1950–79)

- List of New England hurricanes

- Hurricane Agnes

- Tropical Storm Doria (1971)

- Hurricane Floyd

- Hurricane Irene

- Other storms of the same name

Notes

- All damage totals are in 1955 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

References

- 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- Gordon E. Dunn; Walter R. Davis; Paul L. Moore (December 1955). "Hurricanes of 1955" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. United States Weather Bureau. 83 (12): 315, 318–320, 323–326. Bibcode:1955MWRv...83..315D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1955)083<0315:HO>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Hurricane Research Division; National Hurricane Center (June 18, 2013). Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2) (Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original (TXT) on August 1, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- Chris Landsea; et al. (May 2015). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- Chronological List of All Continental United States Hurricanes: 1851 – 2012 (Report). Hurricane Research Division. June 2013. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- Gerald Grossman; Rodenhuis (June 1975). "The Effects of Release of Latent Heat on the Vorticity of a Tropical Storm over Land". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 103 (6): 490, 495. Bibcode:1975MWRv..103..486G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1975)103<0486:TEOROL>2.0.CO;2.

- William T. Chapman; Young T. Sloan (1955). "The Paths of Hurricanes Connie and Diane" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. United States Weather Bureau. 83 (5): 171, 173. Bibcode:1955MWRv...83..171C. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1955)083<0171:TPOHCA>2.0.CO;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- Preliminary Report of Hurricane Diane and Floods in Northeast – August 1955 (PDF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau. August 25, 1955. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- "Hurricane 'Diane' Sweeps into North Carolina". Greensburg Daily Tribune. United Press. August 17, 1955. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "Booming Guns Herald Burke as Navy Chief". Miami Daily News. No. 95. Associated Press. August 17, 1955. p. 8A. Retrieved February 13, 2013 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane Diane Barreling Toward Carolina Shoreline on 115 Mile an Hour Winds". Schenectady Gazette. Associated Press. August 16, 1955. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Rick Schwartz (2007). Hurricanes and the Middle Atlantic States. United States: Blue Diamond Books. pp. 215–220. ISBN 978-0-9786280-0-0. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- Roger D. Greene (October 2, 1955). "Hurricane Experts Hold Differing Views; All Face Storm of Criticism from Public". Eugene Register-Guard. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- Irene Corbally Kuhn (September 1, 1955). "Government Weather vs. Private Service". Meriden Journal. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "Flood Forecasting Science Wasn't Equal to Northeast Disaster". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. August 23, 1955. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Stan Freeman (August 14, 2005). "Diane caught WMass off guard". The Republican. Archived from the original on August 21, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- Floods of August – October 1955: New England to North Carolina. Washington, D.C.: United States Geological Survey. 1960. pp. 15, 27. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- Maryellen Fillo (August 15, 2005). "Now, Dams And Reservoirs, Doppler And Satellites". The Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- Drew Pearson (November 10, 1955). "Washington Merry-Go-Round". The Lewiston Daily Sun. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- Namias, Jerome; Dunn, Carlos R. (August 1955). "The Weather and Circulation of August 1955" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. United States Weather Bureau. 83 (8): 163. Bibcode:1955MWRv...83..163N. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1955)083<0163:TWACOA>2.0.CO;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 16, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- Howard Frederick Matthai (1955). Floods of August 1955 in the Northeastern States (Report). United States Geological Survey. pp. 1–10. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- "Flood Losses May Reach $1,600,000,000; Ike O.K.'s Big Program". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. August 25, 1955. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- David., Longshore (1998). Encyclopedia of hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0816033986. OCLC 36883906.

- Eric S. Blake; Edward N. Rappaport; Jerry D. Jarrell; Christopher W. Landsea (August 2005). The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2004 (and Other Frequently Requested Facts) (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- Edward N. Rappaport; Jose Fernandez-Partagas; Jack Beven (April 22, 1997). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492– 1996 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- David M. Roth (November 17, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the Southeast (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- David M. Roth (March 6, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Mid– Atlantic (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- David M. Roth (July 29, 2009). Hurricane Diane – August 15–19, 1955 (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- "Potomac Floods at Washington". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. August 19, 1955. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "Losses Heavy in Eight States". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Associated Press. August 22, 1955. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Richard W. Paulson; Edith B. Chase; Robert S. Roberts; David W. Moody (1991). National Water Summary 1988–89. United States: United States Geological Survey. pp. 215–217, 225, 471, 484. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- Nicholas DiGiovanni (August 11, 2005). "Back-to-back storms in 1955 unleashed havoc along Delaware River". New Jersey On-Line. Archived from the original on February 24, 2007. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- David M. Roth (March 6, 2013). Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in New England (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- David M. Roth (March 6, 2013). Maximum Rainfall caused by Tropical Cyclones and their Remnants Per State (1950–2012) (GIF) (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- Northeast River Forecast Center. The Floods of Hurricane Connie and Diane (Report). National Weather Service. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Dick Ahles (August 14, 2005). "Memories of a Flood, 50 Years Later". New York Times. p. 6. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- "Havoc of Floods Appears Worst in Connecticut". The Free Lance-Star. Associated Press. August 23, 1955. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Flood Insurance Study: Norfolk County, Massachusetts (PDF) (Report). Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2012. p. 27–28, 31, 39. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 22, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- "Death, Disease Stalk Ebbing Flood; 183 perish". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. August 22, 1955. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "The Connecticut Floods of 1955: A Fifty-Year Perspective". Connecticut State Library. 2012. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- "Americans Open Their Hearts". Spokane Daily Chronicle. September 8, 1955. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "Lodi Asked to Help in Relief". Lodi News-Sentinel. August 26, 1955. Archived from the original on May 22, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "Prepare to Curb Losses via Storm". The Times-News. United Press. August 28, 1956. Archived from the original on May 20, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- "Eisenhower is Happy Man While Fishing and Cooking". The Reading Eagle. Associated Press. September 20, 1955. Archived from the original on May 22, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Peter Edson (September 9, 1955). "Individual Flood Victims Find Aid in Federal Loans". The Victoria Advocate. National Newspaper Association. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Peter Edson (November 25, 1955). "Effort to Flood-Proof Disaster Victims Lags". The Newburgh News. National Newspaper Association. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- "Federal Insurance Program Proposed". Lodi News-Sentinel. United Press. October 30, 1955. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- Elliott Mittler; Leigh Morgan; Marc Shapiro; Kristen Y. Grill (October 2006). State Roles and Responsibilities in the National Flood Insurance Program (PDF) (Report). American Institutes for Research. p. 16. Archived from the original on December 24, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (September 1999). A Report to the United States Congress on Compliance with the National Flood Insurance Program (Report). Federal Reserve Board. Archived from the original on July 30, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- Stories: Tocks Island Dam Controversy (Report). National Park Service. February 1, 2013. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- David Crosby (2009). Scranton Railroads. United States. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7385-6518-7. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "Pennsylvania Food Scarce; Typhoid Feared". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. August 22, 1955. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "Packaged Water Urged During Time of Disaster". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. September 11, 1956. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- "Shapp Scraps Proposal for Gasoline Tax". Beaver County Times. United Press. August 7, 1972. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- "Shapp Will Outline Shovel-Out Plans". Beaver County Times. United Press. June 28, 1972. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- "Ike's Doctrine Adopted". The Washington Observer. Associated Press. March 7, 1957. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- Lloyd R. Rochelle (December 22, 1955). "Tax Wrangle in Harrisburg Tops Political News in 1955". The News-Dispatch. United Press. Archived from the original on May 12, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- Connecticut Hurricane, Torrential Rain, Floods (DR-42) (Report). Federal Emergency Management Agency. Archived from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- Patrick Johnson (March 31, 2010). "Rain causes basement flooding". The Republican. Archived from the original on August 22, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2013.

- "Storm Sets Record in New England: Two Dead". The News. October 22, 1996. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- Gary Padgett; Jack Beven; James Lewis Free; Sandy Delgado (May 23, 2012). Subject: B3) What storm names have been retired? (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on December 6, 2006. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- Dick Bothwell (September 26, 1960). "Something's To Be Done About Weather". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- Eric S. Blake; Ethan J. Gibney (August 2011). The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and Other Frequently Requested Hurricane Facts) (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 21, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- McCarthy Earls, Eamon. "Twisted Sisters: How Four Superstorms Forever Changed the Northeast in 1954 & 1955." Franklin: Via Appia Press (www.viaappiapress.com), 2014. ISBN 978-0982548578