Hurricane Gilbert

Hurricane Gilbert was the second most intense tropical cyclone on record in the Atlantic basin in terms of barometric pressure, only behind Hurricane Wilma in 2005. An extremely powerful tropical cyclone that formed during the 1988 Atlantic hurricane season, Gilbert peaked as a Category 5 strength hurricane that brought widespread destruction to the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, and is tied with 1969's Hurricane Camille as the second-most intense tropical cyclone to make landfall in the Atlantic Ocean. Gilbert was also one of the largest tropical cyclones ever observed in the Atlantic basin. At one point, its tropical storm-force winds measured 575 mi (925 km) in diameter. In addition, Gilbert was the most intense tropical cyclone in recorded history to strike Mexico.[2]

| Category 5 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

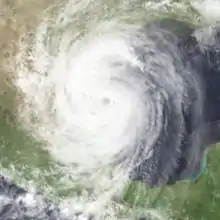

Hurricane Gilbert near peak intensity off the Yucatan Peninsula on September 13 | |

| Formed | September 8, 1988 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 19, 1988 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 185 mph (295 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 888 mbar (hPa); 26.22 inHg (Second-lowest recorded in the Atlantic Ocean) |

| Fatalities | 318 total |

| Damage | $2.98 billion (1988 USD) (Costliest in Jamaican history[1]) |

| Areas affected | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Central America, Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, Texas, South Central United States, Midwestern United States, Western Canada |

| Part of the 1988 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The seventh named storm and third hurricane of the 1988 Atlantic hurricane season, Gilbert developed from a tropical wave on September 8 while located 400 mi (640 km) east of Barbados. Following intensification into a tropical storm the next day, Gilbert steadily strengthened as it tracked west-northwestward into the Caribbean Sea. On September 10, Gilbert attained hurricane intensity, and rapidly intensified into a Category 3 hurricane on September 11. After striking Jamaica the following day, rapid intensification occurred once again, and the storm became a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale with peak 1-minute sustained winds of 185 mph (295 km/h), late on September 13. Gilbert then weakened slightly, and made landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula later that day while maintaining Category 5 intensity. After landfall, Gilbert weakened rapidly over the Yucatán Peninsula, and emerged into the Gulf of Mexico as a Category 2 storm on September 15. Gradual intensification occurred as Gilbert tracked across the Gulf of Mexico, and the storm made landfall as a Category 3 hurricane in mainland Mexico on September 16. The hurricane gradually weakened after landfall, and eventually dissipated on September 19 over the Midwestern United States. On the island of Cozumel, 900 millibars were recorded when the Hurricane Gilbert made landfall as a category 5 hurricane with winds of 165 mph.

Gilbert wrought havoc in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico for nearly nine days. In total, it killed 318 people and caused about $2.98 billion (1988 USD) in damages over the course of its path. As a result of the extensive damage caused by Gilbert, the World Meteorological Organization retired the name in the spring of 1989; it was replaced with Gordon for the 1994 hurricane season.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origins of Hurricane Gilbert trace back to an easterly tropical wave—an elongated low-pressure area moving from east to west—that crossed the northwestern coast of Africa on September 3, 1988. Over the subsequent days, the wave traversed the tropical Atlantic and developed a broad wind circulation extending just north of the equator. The system remained disorganized until September 8, when satellite images showed a defined circulation center approaching the Windward Islands. The following day, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) classified it as the twelfth tropical depression of the annual hurricane season using the Dvorak technique, when it was located about 400 mi (640 km) east of Barbados. The depression proceeded toward the west-northwest, and while moving through the Lesser Antilles near Martinique, it gained enough strength to be designated as Tropical Storm Gilbert.[3]

After becoming a tropical storm, Gilbert underwent a period of significant strengthening. Passing to the south of Dominican Republic and Haiti, it became a hurricane late on September 10 and further strengthened to Category 3 intensity on the Saffir–Simpson scale the next day. At that time, Gilbert was classified as a major hurricane with sustained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure 960 mbar (hPa; 28.35 inHg). On September 12, the hurricane made landfall on the eastern coast of Jamaica at this intensity; its 15 mi (25 km)-wide eye moved from east to west across the entire length of the island.[3][4]

| Most intense Atlantic hurricanes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Pressure | ||

| hPa | inHg | ||||

| 1 | Wilma | 2005 | 882 | 26.05 | |

| 2 | Gilbert | 1988 | 888 | 26.23 | |

| 3 | "Labor Day" | 1935 | 892 | 26.34 | |

| 4 | Rita | 2005 | 895 | 26.43 | |

| 5 | Allen | 1980 | 899 | 26.55 | |

| 6 | Camille | 1969 | 900 | 26.58 | |

| 7 | Katrina | 2005 | 902 | 26.64 | |

| 8 | Mitch | 1998 | 905 | 26.73 | |

| Dean | 2007 | ||||

| 10 | Maria | 2017 | 908 | 26.81 | |

| Source: HURDAT[2] | |||||

Gilbert strengthened rapidly after emerging from the coast of Jamaica. As the hurricane brushed the Cayman Islands, a reporting station on Grand Cayman recorded a wind gust of 156 mph (252 km/h) as the storm passed just to the southeast on September 13. Explosive intensification continued until Gilbert reached a minimum pressure of 888 mbar (hPa; 26.22 inHg) with maximum sustained flight-level winds of 185 mph (295 km/h), having intensified by 72 mbar in a space of 24 hours.[nb 1][3] This pressure was the lowest ever observed in the Western Hemisphere and made Gilbert the most intense Atlantic hurricane on record until it was surpassed by Hurricane Wilma in 2005.[2]

Gilbert then weakened some, but remained a Category 5 hurricane as it made landfall for a second time on the island of Cozumel, and then a third time on Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula on September 14.[3][6] This made it the first Category 5 hurricane to make landfall in the Atlantic basin since Hurricane David hit Hispaniola in 1979. The minimum pressure at landfall in Cozumel was estimated to be 900 mbar (26.6 inHg), along with maximum sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h).[6] The storm weakened quickly while crossing land before it emerged into the Gulf of Mexico as a Category 2 hurricane.[7] Gilbert re-strengthened rapidly, however, and made landfall for a final time as a Category 3 hurricane near La Pesca, Tamaulipas on September 16, with winds of about 125 mph (201 km/h).[3]

On September 17, Gilbert brushed the inland city of Monterrey, Nuevo León before taking a sharp turn to the north. The storm spawned 29 tornadoes in Texas on September 18, and then moved across Oklahoma. It was absorbed by a low-pressure system over Missouri on September 19, and finally became extratropical over Lake Michigan.[3]

Preparations

Late on September 10, a tropical storm warning was issued by the National Hurricane Center for the southern coast of the Dominican Republic alongside a hurricane watch for the Barahona Peninsula. The hurricane watch for Barahona was upgraded to a hurricane warning early on September 11. Later that day, hurricane watches were posted for the Dominican Republic's southern coast, Jamaica, and the southern coast of Cuba east of Cabo Cruz; the hurricane watch in Jamaica was upgraded to a hurricane warning by the end of the day. Hurricane warnings for the southern coast of Haiti were also posted on September 11.[8] Cayman Airways evacuated residents from the Cayman Islands ahead of Gilbert.[9]

On September 12, a hurricane watch was issued for the Cayman Islands, and the hurricane watch for the southern coast of Cuba was extended to Cienfuegos, with the portion of the watch east of Camagüey upgraded to a hurricane warning. That evening, the Yucatán Peninsula was placed under a hurricane watch between Felipe Carrillo Puerto and Progreso. This area included the resort cities of Cancún and Cozumel.[8] The following day, hurricane watches were posted for Pinar del Río and Isla de la Juventud, and the Cayman Islands were placed under a hurricane warning.[8] The watches in western Cuba and the Yucatán Peninsula were replaced with warnings at about mid-day September 13.[10] As Gilbert approached the Yucatán Peninsula on September 14, the hurricane warning in the region was extended to cover the entire coast between Chetumal and Champotón, while a hurricane watch was posted for the northern district of Belize.[10]

Once Gilbert entered the Gulf of Mexico on September 15, hurricane watches were posted for the portion of the shore between Port Arthur and Tampico. Around noon that day, the hurricane watch was upgraded to a hurricane warning between Tampico and Port O'Connor.[10]

Texas governor Bill Clements issued a decree allowing municipalities to lift laws in the name of public safety, including contraflow lane reversals[11] and speed limits.[12]

Impact

| Country | Deaths | Ref | Damage | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 202 | [13] | $2 billion | [13] |

| Jamaica | 45 | [13] | $700 million | [13] |

| Haiti | 30 | [13] | $91.3 million | [14] |

| Guatemala | 12 | [13] | Unknown | |

| Honduras | 12 | [13] | Unknown | |

| Dominican Republic | 5 | [13] | >$1 million | [15] |

| Venezuela | 5 | [13] | $3 million | |

| United States | 3 | [13] | $80 million | [16] |

| Costa Rica | 2 | [13] | Unknown | |

| Nicaragua | 2 | [13] | Unknown | |

| St. Lucia | 0 | $740,000 | [17] | |

| Puerto Rico | 0 | $200,000 | [17] | |

| Total | 318 | $2.98 billion | ||

Gilbert claimed 318 lives, mostly in Mexico. Exact monetary damage figures are not available, but the total for all areas affected by Gilbert is estimated to be near $2.98 billion (1988 USD).

Eastern Caribbean and Venezuela

As a tropical storm, Gilbert brought high winds and heavy rains to many of the eastern Caribbean islands.[17] In St. Lucia heavy rains peaking at 12.8 in (330 mm) in Castries resulted in flash flooding and mudslides, though no major structural damage was reported.[18][19] At Hewanorra International Airport, a dam ruptured and flooded one of the runways.[18] Offshore, six fishermen went missing as Gilbert approached the Lesser Antilles.[19] Banana crop losses from the storm in St. Lucia reached $740,000, with Guadeloupe, St. Vincent, and Dominica reporting similar damage.[17] Several mudslides were reported in Dominica, though no damage resulted from them. Roughly 5 in (130 mm) of rain fell in Barbados, leading to flash floods and prompting officials to close schools and government offices.[18] The U.S. Virgin Islands experienced widespread power outages and flooding, with many residents losing electricity for several days. Damage was less severe in the nearby British Virgin Islands, where only some flooding and power outages took place. In Puerto Rico, dozens of small communities lost power and agricultural losses reached $200,000.[17]

In Venezuela, outflow bands from Gilbert produced extreme torrential rain which triggered widespread flash floods and landslides in the northern part of the country, killing five people and leaving hundreds homeless.[20][21] Damage from the storm was estimated at $3 million.[22] A combined and confirmed death toll of seven dead from the Dominican Republic and Venezuela.[23]

Hispaniola

Heavy rains from the outer bands of Hurricane Gilbert triggered significant flooding in the Dominican Republic and Haiti. At least nine people perished in the Dominican Republic as many rivers, including the Yuna, overtopped their banks.[15] The main electrical relay station in Santo Domingo was damaged by the storm, causing a temporary blackout for much of the city.[24] Losses in the country were estimated in the millions of dollars.[15] In nearby Haiti, more substantial losses took place; 53 people died,[14] including 10 offshore. Most of the casualties took place in the southern part of the country. The port of Jacmel was reportedly destroyed by 10 ft (3.0 m) waves stirred up by the hurricane.[15] In light of extensive damage, the government of Haiti declared a state of emergency for the entire southern peninsula.[24] Losses throughout Haiti were estimated at $91.2 million.[14]

Jamaica

Hurricane Gilbert produced a 19 ft (5.8 m) storm surge and brought up to 823 millimetres (32.4 in) of rain in the mountainous areas of Jamaica,[25] causing inland flash flooding. 49 people died.[20] Prime Minister Edward Seaga stated that the hardest hit areas near where Gilbert made landfall looked "like Hiroshima after the atom bomb."[26] The storm left $700 million (1988 USD) in damage from destroyed crops, buildings, houses, roads, and small aircraft.[27] Two people eventually had to be rescued because of mudslides triggered by Gilbert and were sent to the hospital. The two people were reported to be fine. No planes were going in and out of Kingston, and telephone lines were jammed from Jamaica to Florida.[9]

As Gilbert lashed Kingston, its winds knocked down power lines, uprooted trees, and flattened fences. On the north coast, 20 feet (6.1 m) waves hit, forcing hotels to be evacuated in the popular tourist destination. Kingston's airport reported severe damage to its aircraft, and all Jamaica-bound flights were cancelled at Miami International Airport.[9] Unofficial estimates state that at least 30 people were killed around the island. Estimated property damage reached more than $200 million. More than 100,000 houses were destroyed or damaged and the country's banana crop was largely destroyed. Hundreds of miles of roads and highways were also heavily damaged.[28] Reconnaissance flights over remote parts of Jamaica reported that eighty percent of the homes on the island had lost their roofs. The poultry industry was also wiped out; the damage from agricultural loss reached $500 million (1988 USD). Hurricane Gilbert was the most destructive storm in the history of Jamaica and the most severe storm since Hurricane Charlie in 1951.[29]

Cayman Islands

Gilbert passed 30 miles (48 km) to the south of the Cayman Islands early on September 13, with one reported gust of 157 mph (253 km/h). However, the islands largely escaped the hurricane due to Gilbert's quick forward motion. Damage was mitigated because the depth of the water surrounding the islands limited the height of the storm surge to 5 ft (1.5 m) There was very severe damage to crops, trees, pastures, and a number of private homes.[30] At least 50 people were left homeless and losses were expected to be in the millions.[15]

Central America and Mexico

| Most intense landfalling Atlantic hurricanes Intensity is measured solely by central pressure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Landfall pressure |

| 1 | "Labor Day"[nb 2] | 1935 | 892 mbar (hPa) |

| 2 | Camille | 1969 | 900 mbar (hPa) |

| Gilbert | 1988 | ||

| 4 | Dean | 2007 | 905 mbar (hPa) |

| 5 | "Cuba" | 1924 | 910 mbar (hPa) |

| Dorian | 2019 | ||

| 7 | Janet | 1955 | 914 mbar (hPa) |

| Irma | 2017 | ||

| 9 | "Cuba" | 1932 | 918 mbar (hPa) |

| 10 | Michael | 2018 | 919 mbar (hPa) |

| Sources: HURDAT,[2] AOML/HRD,[32] NHC[33] | |||

Across parts of northern Central America, heavy rains from the outer bands of Hurricane Gilbert triggered deadly flash floods. Its rainfall and high winds reached Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras. In Honduras, at least eight people were killed and 6,000 were left homeless. Additionally, approximately 27,000 acres (11,000 hectares) of crops were flooded.[34] Sixteen people perished in Guatemala and another five died in Nicaragua, leaving a total of 21 people dead in Central America.[35]

35,000 people were left homeless and 83 ships sank when Gilbert struck the Yucatán Peninsula. 60,000 homes were destroyed, and damage was estimated at between $1 and 2 billion (1989 US$).[36] In the Cancún region, Gilbert produced waves 7 m (23 ft) high, washing away 60% of the city's beaches; the storm surge from the storm penetrated up to 5 km (3.1 mi) inland.[37] A further loss of $87 million (1989 USD) due to a decline in tourism was estimated for the months of October, November and December in 1988.[38] Rainfall in the Yucatán Peninsula peaked at 13.78 inches (350 mm) in Progreso.[39]

As Gilbert lashed the third largest city of Mexico, Monterrey, it brought very high winds, torrential rains, and extensive flash floods. More than 60 people died from raging flood waters, and it was feared that more than 150 people died when five buses carrying evacuees were overturned in the raging floodwaters. Six policemen died when they were swept away while trying to rescue passengers on buses stranded by the Santa Catarina River.[36][40] The residents of Monterrey had no power or drinking water, and most telephone lines were down. As the water receded, vehicles began appearing with their wheels up, jammed with mud and rocks. Quintana Roo Governor Miguel Borge reported that damages in Cancún were estimated at more than 1.3 billion Mexican pesos (1988 pesos; $500 million in USD). More than 5,000 American tourists were evacuated from Cancún. In Saltillo, five people died in road accidents caused by heavy rain, and almost 1,000 were left homeless.[40] Rainfall in northeastern Mexico peaked at over 10 inches (250 mm) in localized areas of inland Tamaulipas.[39] In Coahuila, rainfall from Gilbert caused the deaths of 5 people who were swept away by rising waters. Among these were a paramedic and a pregnant woman who died when a Mexican Red Cross ambulance fell into a flooded arroyo near Los Chorros after a bridge collapsed.[41] Gilbert dumped torrential rains and spawned some tornadoes.[42] In Quintana Roo, Gilbert caused significant defoliation in the jungle. The debris eventually fueled a fire in 1989, which ultimately burned 460 sq mi (1,200 km2).[43]

United States

Despite concerns that Texas might suffer a direct hit, there was only minor damage reported in southern Texas from Gilbert's landfall 60 miles (97 km) to the south. Winds gusted to hurricane force in a few places, but the main impact felt in the state was from beach erosion caused by a 3-5-foot storm surge, and tornadoes, which mainly affected the San Antonio area. 29 tornadoes were spawned by Gilbert in Texas, at least two of which were killer tornadoes. Estimates ranged from 30 to more than 60 hitting 25 Texas counties. Nine of them hit San Antonio, where a 59-year-old woman was killed as she slept in her mobile home. 40 tornadoes were spawned in an area from Corpus Christi and Brownsville north to San Antonio and west to Del Rio.[44][45] Gilbert also provided a good look at a particular unusual hurricane-spawned tornado in Del Rio, two hundred and fifty miles from the ocean. It was the first type of tornado to be captured on film since a tornado spun from Hurricane Agnes in 1972. Despite the massive appearance of the tornado, it did not produce a wide range damage path. Few hurricane-spawned tornadoes do. In the state, a major disaster was declared on October 5, 1988.[46]

Oklahoma recorded the highest rainfall in the United States at 8.6 inches (220 mm), in Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge. Isolated locations in Texas and Oklahoma reported over 7 inches (180 mm), while moderate rainfall of up to 3 inches (76 mm) fell in central Michigan. Overall damage in the United States was estimated at $80 million (1988 USD).[16][39]

Aftermath, retirement, and records

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 3429.0 | 135.00 | Nov. 1909 Hurricane | Silver Hill Plantation | [47] |

| 2 | 1524.0 | 60.00 | Flora 1963 | Silver Hill | [48] |

| 3 | 1057.9 | 41.65 | Michelle 2001 | [49] | |

| 4 | 950.0 | 37.42 | Nicole 2010 | Negril | [50] |

| 5 | 938.3 | 36.94 | Gilda 1973 | Top Mountain | [48] |

| 6 | 863.6 | 34.00 | June 1979 T.D. | Western Jamaica | [51] |

| 7 | 823.0 | 32.40 | Gilbert 1988 | Interior mountains | [49] |

| 8 | 733.8 | 28.89 | Eta 2020 | Moore Town, Jamaica | [52] |

| 9 | 720.6 | 28.37 | Ivan 2004 | Ritchies | [53] |

| 10 | 713.5 | 28.09 | Sandy 2012 | Mill Bank | [54] |

The overall property damage was estimated at $2.98 billion (1988 USD). Earlier estimates put property damage from Gilbert at $2.5 billion but were as high as $10 billion. A final count of Hurricane Gilbert's victims is not possible because many people remained missing in Mexico, but the total confirmed death toll was 433 people.[44] Gilbert was the worst hurricane in the history of Jamaica and the most destructive tropical cyclone on record to strike Mexico. Due to its widespread impact, extensive damage, and extreme loss of life, the name Gilbert was retired in the spring of 1989 by the World Meteorological Organization and was the first name to be retired since Hurricane Gloria in 1985. The name will never again be used for another Atlantic hurricane.[55] The name was replaced by Gordon during the 1994 Atlantic hurricane season.[56]

The destruction in Jamaica was so heavy that Lovindeer, one of the country's leading dance hall DJs, released a single called Wild Gilbert a few days after the storm. It was the fastest selling reggae record in the history of Jamaican music.[57] In 1989, the PBS series Nova released the episode "Hurricane!" that featured Gilbert (later modified in 1992 to reflect Hurricane Andrew and Hurricane Iniki).

On September 13, Hurricane Gilbert attained a record low central pressure of 888 mb (hPa; 26.22 inHg), surpassing the previous minimum of 892 hPa (26.34 inHg) set by the 1935 Labor Day hurricane. This made it the strongest tropical cyclone on record in the north Atlantic basin at the time. It was surpassed by Hurricane Wilma in 2005, which attained a central pressure of 882 hPa (26.05 inHg).[2] Gilbert is the most intense tropical cyclone on record to strike Jamaica. The storm also produced record-breaking rainfall in Jamaica, amounting to 27.56 in (700 mm). This ranked it as the fourth-wettest known storm to strike Jamaica; however, it has since been surpassed by three other storms.[20]

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Atlantic hurricane records

- List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- Hurricane Debby (1988) – A Category 1 hurricane that impacted Eastern Mexico

- Hurricane Diana (1990) – A Category 2 hurricane that devastated Eastern Mexico

Notes

- While the storm was active, the National Hurricane Center estimated the minimum pressure to be 885 mbar (885 hPa; 26.1 inHg) based on reports from weather reconnaissance aircraft. However, this estimate was revised to 888 mbar (888 hPa; 26.2 inHg) during post-storm analysis, as it was discovered that the pressure transducer used to calculate the aircraft's static pressure had a bias towards low pressures.[5]

- Storms with quotations are officially unnamed. Tropical storms and hurricanes were not named before the year 1950.[31]

References

- "1988- Hurricane Gilbert". Hurricane Science.org. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. September 19, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- Gil Clark (1988-10-26). Preliminary Report Hurricane Gilbert: 08–19 September 1988 (GIF) (Report). 1988 Atlantic Hurricane Season: Atlantic Storm Wallet Digital Archives. National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- Pan American Health Organization Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Relief Coordination Program. (1999-02-20) "The Hurricane and its Effects: Hurricane Gilbert - Jamaica" (PDF). Centro Regional de Información sobre Desastres América Latina y El Caribe. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-22. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- H. E. Willoughby; J. M. Masters; C. W. Landsea (December 1989). "A Record Minimum Sea Level Pressure Observed in Hurricane Gilbert". Monthly Weather Review. 117 (12): 2825. Bibcode:1989MWRv..117.2824W. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<2824:ARMSLP>2.0.CO;2.

- Gil Clark (2008-08-20). "Hurricane Gilbert Preliminary Report (Page 2 - 1988)" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- Gil Clark (1988). "Hurricane Gilbert Preliminary Report (Page 9)" (GIF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- Gil Clark (1988-10-26). Preliminary Report Hurricane Gilbert: 08–19 September 1988 (GIF) (Report). 1988 Atlantic Hurricane Season: Atlantic Storm Wallet Digital Archives. National Hurricane Center. p. 11. Retrieved 2011-12-31.

- Staff writers; wire reports (1988-09-13). "Cayman Airline Evacuates Residents As Gilbert Nears". Palm Beach Post. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- Gil Clark (1988-10-26). Preliminary Report Hurricane Gilbert: 08–19 September 1988 (GIF) (Report). 1988 Atlantic Hurricane Season: Atlantic Storm Wallet Digital Archives. National Hurricane Center. p. 12. Retrieved 2011-12-31.

- "Killer storm heads for US coast". New Straits Times. 1988-09-17. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- "El paso del huracán 'Gilberto', televisado en directo". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. 1988-09-17. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- Lawrence, Miles B; Gross, James M (October 1, 1989). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1988". Monthly Weather Review. 117 (10): 2248–225. Bibcode:1989MWRv..117.2248L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.212.8973. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<2248:AHSO>2.0.CO;2.

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. "EM-DAT: The Emergency Events Database". Université catholique de Louvain.

- "Hurricane Gilbert's swathe of death and disaster". United Press International. New York, United States: The Independent. September 19, 1988. p. 10. (accessed through LexisNexis)

- Blake, Eric S; Landsea, Christopher W; Gibney, Ethan J; National Hurricane Center (August 2011). The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (And Other Frequently Requested Hurricane Facts) (PDF) (NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 21, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- "Casualties And Damage From Hurricane Gilbert At A Glance". Associated Press. 1988-09-15.

- "Hurricane Gilbert gains strength". United Press International. 1988-09-11.(accessed through LexisNexis)

- "United Press International September 10, 1988, Saturday, AM cycle". United Press International. 1988-09-10. (accessed through LexisNexis)

- Lawrence, Miles B.; Gross, James M. (1989). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1988" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 117 (10): 2253. Bibcode:1989MWRv..117.2248L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.212.8973. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<2248:AHSO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0027-0644. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-14. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- "Hurricane Gilbert: reports from Jamaica, Cuba, Venezuela". BBC. 1988-09-16. (Accessed through LexisNexis)

- "200 mph hurricane batters holiday isle; Hurricane Gilbert". The Times. London, United Kingdom. 1988-09-15. (accessed through LexisNexis)

- "Hurricane Gilbert Sweeps Across The Caribbean". New Straits Times. Associated Press. 1988-09-14. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- "Gilbert left damage throughout all of Caribbean". St. Petersburg Times. Florida, United States. September 16, 1988. p. 12A. (accessed through LexisNexis)

- Ahmad, Rafi, Lawrence Brown, Jamaica National Meteorological Service. "Assessment of Rainfall Characteristics and Landslide Hazards in Jamaica" (PDF). University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-15. Retrieved 2012-06-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Patrick Reyna (1988-09-14). "Jamaica's Premier Reports Island Devastated by Hurricane". Kingston, Jamaica. Associated Press. (accessed through LexisNexis)

- History of Hurricanes and Floods in Jamaica (PDF) (Report). National Library of Jamaica. 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- Joseph B. Treaster (1988-09-13). "Hurricane Is Reported to Damage Over 100,000 Homes in Jamaica". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- Joseph B. Treaster (1988-09-15). "Jamaica Counts the Hurricane Toll: 25 Dead and 4 Out of 5 Homes Roofless". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- Hurricanecity (2012-01-26). "Grand Cayman's history with tropical systems". Hurricanecity. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

- Landsea, Christopher; Dorst, Neal (June 1, 2014). "Subject: Tropical Cyclone Names: B1) How are tropical cyclones named?". Tropical Cyclone Frequently Asked Question. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015.

- Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; Carrasco, Cristina; Charles, Noel; Chenoweth, Michael; Clark, Gil; Delgado, Sandy; Dunion, Jason; Ellis, Ryan; Fernandez-Partagas, Jose; Feuer, Steve; Gamanche, John; Glenn, David; Hagen, Andrew; Hufstetler, Lyle; Mock, Cary; Neumann, Charlie; Perez Suarez, Ramon; Prieto, Ricardo; Sanchez-Sesma, Jorge; Santiago, Adrian; Sims, Jamese; Thomas, Donna; Lenworth, Woolcock; Zimmer, Mark (May 2015). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Metadata). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- Franklin, James (January 31, 2008). Hurricane Dean (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- Cam Rossie (1988-09-16). "Thousands Left Homeless By Hurricane Gilbert; Makes Landfall In Mexico". Matamoros, Mexico. Associated Press. (accessed through LexisNexis)

- "Gilbert leaves big toll". Sunday Herald Sun. Melbourne, Australia. Reuters. 1988-09-19. (accessed through LexisNexis)

- E. Jáuregui (2003-06-11). "Climatology of landfalling hurricanes and tropical storms in Mexico" (PDF). Centro de Ciencias de la Atmósfera, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - León, Mario Alberto (2005-07-18). "'Gilberto', el monstruo de viento y lluvia". esmas.com (in Spanish). Noticieros Televisa. Archived from the original on 2011-07-04. Retrieved 2011-12-31.

- Benigono Aguirre (March 1989). "Cancun Under Gilbert: Preliminary Observations" (PDF). International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters. 7 (1): 69–82. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-20. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- David M. Roth (2006). "Rainfall data for Hurricane Gilbert". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2006-10-16.

- "300 Feared Dead". New Straits Times. Mexico City, Mexico. Associated Press. 1988-09-19. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- Muñoz, Camelia (2009-09-17). "Huracán Gilberto: Hace 21 años fue un caudal de destrucción". El Zócalo (in Spanish). Saltillo: Grupo Zócalo. Retrieved 2012-01-01.

- Peter Applebome (1988-09-17). "HURRICANE ROARS INTO MEXICO AGAIN WITH LESS FORCE". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- Natural Hazards of North America. National Geographic Society. July 1998.

- Thom Marshall (1988-09-25). "Hurricane Gilbert: Aftermath/Gilbert: No normal hurricane". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- Unattributed (2005-07-31). "Then & Now: The tornadoes of 1988". Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- "FEMA: Texas HURRICANE GILBERT". FEMA. Archived from the original on 2012-01-05. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- Paulhaus, J. L. H. (1973). World Meteorological Organization Operational Hydrology Report No. 1: Manual For Estimation of Probable Maximum Precipitation. World Meteorological Organization. p. 178.

- Evans, C. J.; Royal Meteorological Society (1975). "Heavy rainfall in Jamaica associated with Hurricane Flora 1963 and Tropical Storm Gilda 1973". Weather. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 30 (5): 157–161. doi:10.1002/j.1477-8696.1975.tb03360.x. ISSN 1477-8696.

- Ahmad, Rafi; Brown, Lawrence; Jamaica National Meteorological Service (January 10, 2006). "Assessment of Rainfall Characteristics and Landslide Hazards in Jamaica" (PDF). University of Wisconsin. pp. 24–27. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- Blake, Eric S.; National Hurricane Center (March 7, 2011). Tropical Storm Nicole (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Frank, Neil L.; Clark, Gilbert B. (1980). "Atlantic Tropical Systems of 1979". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 108 (7): 971. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1980)108<0966:ATSO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0027-0644. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Richard J. Pasch and David P. Roberts (2021-06-09). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Eta - 31 October-13 November 2020. National Hurricane Center Retrieved on June 12, 2021.

- Stewart, Stacey R.; National Hurricane Center (December 16, 2004). Hurricane Ivan (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Blake, Eric S; Kimberlain, Todd B; Berg, Robert J; Cangialosi, John P; Beven II, John L (February 12, 2013). Hurricane Sandy: October 22 – 29, 2012 (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

- National Hurricane Center (2009). "Retired Hurricane Names Since 1954". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2015-06-07. Retrieved 2009-09-13.

- "1994 Hurricane Names". The Public Square. 1994-09-22. Retrieved 2011-04-06.

- David Barker; David Miller (1990). "Hurricane Gilbert: anthropomorphising a natural disaster". Area. 22 (2): 107–116. JSTOR 20002812.