Hurricane Lili

Hurricane Lili was the second costliest, deadliest, and strongest hurricane of the 2002 Atlantic hurricane season, only surpassed by Hurricane Isidore, which affected the same areas around a week before Lili. Lili was the twelfth named storm, fourth hurricane, and second major hurricane of the 2002 Atlantic hurricane season. The storm developed from a tropical disturbance in the open Atlantic on September 21. It continued westward, affecting the Lesser Antilles as a tropical storm, then entered the Caribbean. As it moved west, the storm dissipated while being affected by wind shear south of Cuba, and regenerated when the vertical wind shear weakened. It turned to the northwest and strengthened up to category 2 strength on October 1. Lili made two landfalls in western Cuba later that day, and then entered the Gulf of Mexico. The hurricane rapidly strengthened on October 2, reaching Category 4 strength that afternoon. It weakened rapidly thereafter, and hit Louisiana as a Category 1 hurricane on October 3. It moved inland and dissipated on October 6.[1]

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

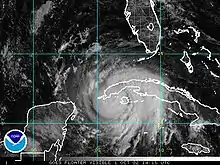

Hurricane Lili near peak intensity in the Gulf of Mexico on October 2 | |

| Formed | September 21, 2002 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | October 4, 2002 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 145 mph (230 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 938 mbar (hPa); 27.7 inHg |

| Fatalities | 13 direct, 2 indirect |

| Damage | $1.16 billion (2002 USD) |

| Areas affected | Windward Islands, Haiti, Jamaica, Cuba, Yucatan Peninsula, Cayman Islands, Louisiana |

| Part of the 2002 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Lili caused extensive damage through the Caribbean, particularly to crops and poorly built homes.[2] Mudslides were common on the more mountainous islands, particularly Haiti and Jamaica.[3] In the United States, the storm cut off the production of oil within the Gulf of Mexico, and caused severe damage in parts of Louisiana. Lili was also responsible for severe damage to the barrier islands and marshes in the southern portion of the state. Total damage amounted to $925 million (2002 USD), and the storm killed 15 people during its existence.[1][4]

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

A tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa on September 16. A low level center of circulation developed from a tropical disturbance spawned by this tropical wave midway between the African coast and the Caribbean on September 20. The next day, the system gained sufficient organization to become a tropical depression.[1][5] The depression moved westward in excess of 20 mph (32 km/h), and reached tropical storm strength-becoming Tropical Storm Lili as it passed through the Windward Islands.[6] The cyclone continued to intensify as it moved west through the Caribbean Sea, reaching an initial peak strength of 70 mph (110 km/h) on the morning of September 24.[7] This was immediately followed by an abrupt weakening, and the storm's maximum sustained winds dropped to 40 mph (64 km/h) later that day.[8] The sudden weakening was attributed to strong southerly vertical shear.[9] The system degenerated into an open tropical wave the next morning, and remained in that state for nearly two days.

Lili regenerated near Jamaica on the evening of September 26 and gradually turned more to the west-northwest while strengthening.[1] The system became a hurricane on September 30, just after passing through the Cayman Islands.[10] The storm continued on its course while continuing to intensify, and made landfall twice the next day, on the Isle of Youth and near Pinar del Río as a Category 2 hurricane.[11] Lili emerged over the Gulf of Mexico later that day, having lost little strength during its overland passage.[1][12]

The system turned to the northwest and sped up, becoming a major hurricane on October 2 while 365 miles (587 km) south-southeast of New Orleans.[13] This intensification continued, aided by warm sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico and good outflow.[14] The system reached its peak strength of category 4 intensity, with winds of 145 mph (233 km/h), during that afternoon.[15]

This strength was not maintained for long. The storm began to quickly weaken in the early morning hours of October 3,[16] and this rapid weakening continued until the hurricane's final landfall near Intracoastal City, Louisiana, due to a combination of vertical wind shear, cool waters just offshore Louisiana,[17] and slowly encroaching dry air within its southwest quadrant.[18] By the time of landfall, maximum sustained winds had dropped to 90 mph (145 km/h).[19] The weakening was accompanied by a collapse of the inner eyewall before landfall.[1] The system continued inland, curving to the north-northeast, and dissipated when absorbed by an extratropical low near the Arkansas/Tennessee border on October 6.[1]

Preparations

Tropical storm watches were issued in parts of the Lesser Antilles on September 22. These were upgraded to warnings the next afternoon, and all advisories were dropped late on September 23 once the storm had passed.[1] Over the next week, the islands of Hispaniola, Jamaica, Cuba, the Caymans, and the Yucatán Peninsula were all under advisories of some kind at different times.[1] Hurricane and tropical storm watches were issued for the Gulf Coast on October 1, and were upgraded to warnings the next morning.[1] They were discontinued after the storm moved past the following day.[20]

Because the cyclone affected the islands as a weak tropical storm, preparations were minimal. Two hundred people evacuated their homes in advance of the storm on the islands of St. Vincent and Grenadine.[2] In Jamaica, all schools and universities were closed in advance of the storm, and 17 public shelters were opened on the island.[21]

Preparations were extensive in Cuba. Military officials at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp prepared for the possibility of evacuating their Al Qaeda and Taliban prisoners.[22] A total of 130,000 Cuban citizens, mainly in western portions of the island, evacuated their homes prior to the storm.[23]

Significant action was taken along the Gulf Coast as the threat the storm posed, predicted to come ashore at Category Four strength, became more urgent. Over a half million people evacuated their homes in Texas and Louisiana, including everyone in Iberia Parish.[24] A total of 200,000 people evacuated in Louisiana.[24][25] At least 2,000 volunteers staffed 115 Red Cross shelters in Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, and Alabama.[26] More than 20,000 people stayed in those shelters.[25] The Red Cross also sent over 160,000 meals to the area.[26] A total of 3,000 prison inmates in Texas were evacuated to safer inland locations.[24] The launch of Space Shuttle Atlantis was delayed for five days when the Kennedy Space Center was threatened by the storm, the first time a launch in Florida had been delayed because of weather in Houston.[27] Stores across the warning area were very busy in advance of the storm. In New Iberia, Louisiana, hardware stores ran out of stock,[28] and businesses in Lafayette, Louisiana reported similar shortages.[29]

Collegiate activities were also affected by the storm. Southern University canceled four days of classes because of Lili,[30] and 20 Texas A&M University Galveston, Texas students evacuated to the school's College Station location.[31] The University of South Alabama canceled two athletic events in advance of the storm.[32]

Impact

| State/country | Deaths |

|---|---|

| Saint Lucia | 4 |

| Jamaica | 4 |

| Haiti | 4 |

| Cuba | 1 |

| United States | 2 |

| Total | 15 |

Hurricane Lili was both the second deadliest and the second most devastating hurricane of the 2002 Atlantic hurricane season (Isidore killed 22 people and damaged $1.28 billion worth of property).[33] A total of 13 people died in the Caribbean Islands, and 2 more were killed in the United States.[1] Severe damage to crops and livestock occurred through the Lesser Antilles, and damage to buildings and other infrastructure was reported in other Caribbean nations and the United States.[1]

Lesser Antilles

Lili affected the islands as a tropical storm. Winds in the area were generally below hurricane force, although some gusts exceeded 74 mph (119 km/h).[1] Rainfall of up to 4 inches (100 mm) caused deadly mudslides.[2] The winds, combined with poor construction, tore the roofs off numerous homes and businesses. The majority of the damage was dealt to primarily to the banana crop.[34]

St. Lucia lost at least 75 percent of its banana crop, and hundreds of homes were damaged by the strong winds.[2] Near total loss of electricity, water, and telephone services occurred, and utility systems were heavily damaged.[34] Four people were killed on the island, and total damage was estimated at $20 million (2002 USD)[1][34]

Over 400 homes were damaged in Barbados, and nearly 50 trees were downed by the high gusts. Similar to in St. Lucia, there was significant damage to the nation's banana crop.[34] Extensive loss of electricity and telephone service also occurred. Damage totaled at nearly $200,000 (2002 USD).

Grenada also experienced moderate damage. A total of 14 homes' roofs were damaged, and one was completely destroyed. The island Medical Centre's roof was also damaged, and 12 landslides were reported.[34] There was also mild damage to infrastructure, particularly in St. Patrick's Parish; three bridges were damaged or destroyed, along with seven utility poles and a water main. The entire island was without power at some point, but it was quickly restored in the southern part of the island where damage to the poles themselves was less significant.[34]

St. Vincent and the Grenadines were heavily damaged, especially compared to other islands in the area. Several hundred homes and two schools were damaged, and the Rose Hall Police Station's roof was lost.[34] Still, the majority of damage was dealt to the agricultural industry.[34] In all, damage to the islands totaled $40 million (2002 USD).[34]

Haiti

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 1,447.8 | 57.00 | Flora 1963 | Miragoâne | [35] |

| 2 | 654.8 | 25.78 | Noel 2007 | Camp Perrin | [36] |

| 3 | 604.5 | 23.80 | Matthew 2016 | Anse-á-Veau | [37] |

| 4 | 410.0 | 16.14 | Lili 2002 | Camp Perrin | [38] |

| 5 | 323.0 | 12.72 | Hanna 2008 | Camp Perrin | [39] |

| 6 | 273.0 | 10.75 | Gustav 2008 | Camp Perrin | [40] |

| 7 | 168.0 | 6.614 | Laura 2020 | Port-Au-Prince | [41] |

| 8 | 65.0 | 2.56 | Fox 1952 | Ouanaminthe | [42] |

Lili passed offshore of Haiti as a weakening tropical storm.[1] The storm's major impact was extremely heavy rainfall, in excess of 16 inches (410 mm) near the settlement of Camp-Perrin, Haiti.[43] This caused the Ravine du Sud River to overflow, and submerge buildings in the town. Two people died in the mudslides these rains triggered, and two more drowned in the flooding around Camp-Perrin.[44] The floods also seriously damaged crops and infrastructure; over 1700 homes were damaged and 240 were destroyed. Haiti was affected dramatically and many towns and villages submerged into rivers exceeding their bankfull discharge[44]

Jamaica

Lili affected Jamaica as a strengthening tropical storm. Wind gusts in excess of 70 mph (110 km/h) and rainfall over 2 feet (0.61 m) resulted in damage to homes, crops, and utility systems.[1][21]

Extremely heavy rainfall inundated the island. Cedar Valley recorded the most rainfall, with 23.1 inches (590 mm) measured. This led to prolific flooding that triggered mudslides across the island and killed four people. These floods decimated the island's sugar cane crop, one of the island's principal exports.[21] The resultant flooding caused widespread problems with the infrastructure of the island. All of the island's hospitals had flood damage, and three were also dealt structural damage by the strong winds.[45] The flooding caused latrines and other sewage sources to overflow into the intake sources for the water supply, leading to fear of disease.[45]

Cuba

Lili made landfall as a category two hurricane twice in Cuba, on the Isle of Youth and in the Pinar del Río Province, on October 1. Wind gusts up to 112 mph (180 km/h) and rainfall amounts reaching 6 inches (150 mm) in some places caused damage to homes, businesses and crops. One person was killed.[1][46]

Damage to buildings and other infrastructure was significant. The most severely affected provinces were Pinar del Río and La Habana. A total of 48,000 homes were damaged, 16,000 of them lost their roofs. The province Sancti Spiritus was not affected as severely, as only 945 homes were damaged, with 500 losing their roofs. The provinces in Eastern Cuba, including Guantanamo, suffered similar damage.[47] Electricity outages for whole towns lasted weeks in parts of the western provinces. This led to loss of running water due to unpowered pumps, and deliveries of fresh water had to be made to remote villages.[46] The tobacco and rice crops were badly depleted, but it was difficult to differentiate how much damage was caused by Lili, since Isidore had struck the region just a week earlier.[46][48]

Louisiana

Lili made landfall on the morning of October 3 near Intracoastal City, as a weakening category one hurricane.[1] Wind gusts reaching 120 mph (190 km/h), coupled with over 6 inches (150 mm) of rainfall and a storm surge of 12 feet (3.7 m) caused over $790 million (2002 USD) in damage to Louisiana. A total of 237,000 people lost power, and oil rigs offshore were shut down for up to a week.[49] Crops were badly affected, particularly the sugar cane, damage totaled nearly $175 million (2002 USD). No direct deaths were reported as early warnings and the compact nature of the storm circumvented major loss of life.[50]

Vermillion Parish, the point of landfall, was hardest hit. Wind gusts in excess of 120 mph (190 km/h), along with a storm surge of 12 feet (3.7 m) dealt major damage to nearly 4000 homes.[49] The worst storm surge flooding occurred in Intracoastal City, destroying 20 buildings owned by a helicopter company. One person died after the storm, and 20 were hospitalized for carbon monoxide poisoning.[49]

Acadia Parish was also hard hit, recording wind gusts exceeding 110 mph (180 km/h), and 5 tornadoes touched down in the parish.[49] Thousands of homes were damaged with over 2,500 suffering severe damage. Power across the parish was knocked out, 2 people were injured and one was killed after the storm. Schools in the parish also sustained $1.6 million (2002 USD) in damage.[49]

Mississippi

Lili's outer rainbands dumped large amounts of rain and brought tropical storm force wind gusts to Mississippi.[51] Pascagoula, Mississippi, recorded wind gusts of 41 mph (66 km/h), and Picayune, Mississippi, received 4.14 inches (105 mm) of rainfall. Minor power outages occurred, mainly in southern Mississippi, and combined with the flooding of roads and buildings caused $30 million (2002 USD) in damage. No deaths occurred in Mississippi.[1]

Other areas in the United States

Hurricane Lili's remnants brought heavy rainfall, peaking at four inches in Arkansas, to the Southeast, before dissipating near the Arkansas-Tennessee border. Lili's remnants also caused minimal rainfall in the Lower Tennessee Valley. No major damage was reported.[1]

Aftermath

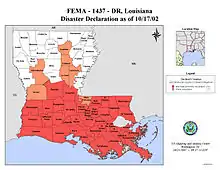

President Bush declared Louisiana a federal disaster area after the storm, making it eligible for assistance.[52] FEMA set up three locations to apply in Mississippi and Louisiana. Applications began pouring in, 153,000 by the time of the deadline.[53][54] Over $311 million in aid was granted to Louisiana.[55] A total of $50 million of that money was in the form of low interest loans, and not actual grants.

Over 1,000 power workers from eight different states went to the worst hit areas to help restore power.[56][57] Seven states sent tree trimmers to help clear debris from power lines and roads to speed the recovery process.[58] In addition, FEMA gave SLEMCO, the state's power company, an $8.6 million grant, which paid for 75% of the damage to the electrical grid there.[59] It took up to four weeks to restore power to all customers.[60]

Hurricane Lili caused great environmental damage to the marshes and barrier islands in Louisiana. Huge fish kills were observed in marshes near the landfall point, and in the Atchafalaya Swamp. The barrier islands to the east of the landfall point, those subjected to the highest surge, were severely eroded. Sand was also deposited behind them into the brackish marshes, burying vegetation. The freshwater marshes were severely damaged by the wind and surge, some of them completely destroyed. The severe erosion created new waterways connecting inland bodies of water with the Gulf of Mexico, which eventually led to further erosion of inland lagoons.[61]

Retirement

The name Lili was retired in the spring of 2003 because of its destruction and deadly Caribbean track, and will never be used again in the Atlantic basin. It was replaced with Laura for the 2008 season.[62] The names Lucy and Lisette were also suggested as possible replacement names for Lili.[63]

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2002

- List of Cuba hurricanes

- List of retired Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Category 4 Atlantic hurricanes

- Hurricane Barry (2019) – Struck a similar area in July 2019.

References

- Miles Lawrence (2002). "National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2015-05-26.

- "Lili leaves trail of destruction in Eastern Caribbean". Jamaica Observer. Associated Press. 2002. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- "Lili killed 4 in Haiti;deaths unreported for a week". USA Today. Associated Press. 2002-10-05. Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- Blake, Eric S; Landsea, Christopher W; Gibney, Ethan J (August 2011). Costliest U.S. Hurricanes 1900 - 2010 (unadjusted): Table 3a: The 30 costliest mainland United States tropical cyclones, 1900-2010, (not adjusted for inflation) (PDF). National Hurricane Center/National Climatic Data Center (NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- Lixion Avila; Eric Blake (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Stacey Stewart (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #9A". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Stacey Stewart (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #13". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Brian Jarvinen; Robert Molleda (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #15". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Brian Jarvinen; Robert Molleda (2002). "National Hurricane Center Forecast Discussion #15". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- James Franklin (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #36". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Jack Beven (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #40A". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Jack Beven (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #41". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Jack Beven (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #44". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Jack Beven (2002). "National Hurricane Center Forecast Discussion #44". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Jack Beven (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #45". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Richard Pasch (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #48". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Chris Cappella. Scientists don't yet know why Lili suddenly collapsed. Retrieved on 2008-05-08.

- Adele Marie Babin. Characteristics of Hurricane Lili'S Intensity Changes. Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2008-05-08.

- Lixion Avila (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #49". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- Lixion Avila (2002). "National Hurricane Center Public Advisory #49B". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- Horace Helps (2002). "News: Caribbean: Tropical Storm Lili — September 2002, Hurricane Lili belts Caymans, 4 dead in Jamaica". Relief Web. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- "United States to move Cuba base detainees if storm nears". The Guardian. London. Reuters. 2002-09-25. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- "Gulf Coast under Lili watch". The St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. 2002. Archived from the original on 2010-12-31. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- Jeffrey Gettleman (2002-10-03). "Thousands Seek Safety as Hurricane Nears Gulf Coast". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- Cable News Network (2002-10-03). "Red Cross shelters thousands from the storm". Cable News Network. Archived from the original on 2008-04-05. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- Bonnie Gillespie (2002). "Team Louisiana Weathers Hurricane Lili". The Red Cross. Archived from the original on 2008-03-13. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- David Cohen (2002-10-02). "Hurricane Lili closes shuttle Mission Control". New Scientist. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- KXAS (2002). "Hurricane Lili Makes Landfall Into Louisiana Coast". National Broadcasting Company. Archived from the original on 2002-10-16. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- Mike Brassfield (2002). "Hurricane Lili runs out of steam". The St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on 2011-05-23. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- Gabrielle Maple (2002). "Back to Back". The Southern Digest. Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- Jeremy Osborne (2002). "Texas Task Force Sent to Galveston". The Batt. Archived from the original on 2013-08-16. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- Jeff Roper (2002). "Hurricane Lili cancels two games". The Vanguard. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- Lixion Avila; Jack Beven; James Franklin; Miles Lawrence; Richard Pasch; Stacey Stewart (2002). "Summary of Tropical Cyclone Activity of 2002". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- Caribbean Disaster Emergency Response Agency (2002). "Situation Reports:Caribbean:Tropical Storm Lili". Relief Web. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- Dunn, Gordon E; Moore, Paul L; Clark, Gilbert B; Frank, Neil L; Hill, Elbert C; Kraft, Raymond H; Sugg, Arnold L (1964). "The Hurricane Season of 1963" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 92 (3): 136. Bibcode:1964MWRv...92..128D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493-92.3.128. ISSN 0027-0644. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Brown, Daniel P (December 17, 2007). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Noel (PDF) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- Stewart, Stacy R (April 3, 2017). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Matthew (PDF) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- Finnigan, Sean (October 4, 2002). Hurricane Lili almost drowns Camp-Perin, Haiti (PDF) (Report). Organisation for the Rehabilitation of the Environment. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- Brown, Daniel P; Kimberlain, Todd B (March 27, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Hanna (PDF) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- Beven II, John L; Kimberlain, Todd B (January 22, 2009). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Gustav (PDF) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- Jeff Masters and Bob Henson (August 24, 2020). "Laura expected to hit Gulf Coast as at least a Category 2 hurricane". Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- Roth, David M. (October 18, 2017). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Organization for the Rehabilitation of the Environment (2002). "Hurricane Lili Was Accompanied by Torrential Rains As it Passed Over Haiti". Organization for the Rehabilitation of the Environment. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- "Lili killed 4 in Haiti; deaths unreported for a week". USA Today. Associated Press. 2002-10-05. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- Pan American Health Organization (2002). "Hurricane Lili in the Caribbean". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- International Federation of the Red Cross (2002). "Press Releases: Caribbean: Tropical Storm Isidore — September 2002, Cuban community left reeling by Isidore and Lili". Relief Web. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- International Federation of the Red Cross (2002). "Situation Reports: Caribbean: Tropical Storm Isidore — September 2002, Caribbean: Hurricane Lili Information Bulletin No. 03/02". Relief Web. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- Office of the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2002). "Caribbean — Tropical Storm Lili OCHA Situation Report No. 8". Relief Web. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- National Weather Service Forecast Office, Lake Charles, Louisiana (2002). "LILI". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 2003-04-17. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kent Kuyper; Marty Mayeaux; Montra Lockwood; Donovan Landreneau; Joe Rua; Lance Escude; Roger Erickson (2002). "Lili '02". NWS WFO Lake Charles, Louisiana. Archived from the original on 2002-12-26. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- National Weather Service Forecast Office, New Orleans, Louisiana (2002). "Post Tropical Cyclone Report...Hurricane Lili". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2002-10-16. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mike Brassfield (2002). "Hurricane Lili Runs Out of Steam". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on 2011-05-23. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (2002). "Louisiana Aid Deadline Looms, 153,000 Have Applied". Federal Emergency Management Agency. Archived from the original on 2007-10-31. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- The New Orleans Channel (2002). "Federal Emergency Management Agency Fans Out After Storms". WDSU. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (2002). "Lili Recovery at More Than a Quarter Billion Dollars". Federal Emergency Management Agency. Archived from the original on 2007-10-31. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- WTVY (2002). "Hurricane Lili Aid". WTVY. Archived from the original on 2013-02-09. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- Melissa Simas (2002). "Utility Workers on Ready for Storm Damage". KAIT. Archived from the original on 2015-12-28. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- Cleco Corporation (2002). "Cleco Power". Cleco Corporation. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (2002). "SWLA Electric Corp To Receive $8.6 million Federal Emergency Management Agency Public Assistance Grant". Federal Emergency Management Agency. Archived from the original on 2007-10-31. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- Storm Work (2002). "Helping Customers and Communities" (PDF). Storm Work. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-03-07. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- Gaye Farris (2002). "USGS scientists monitor coastal damage from Hurricane Lili". USGS. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- World Meteorological Organization (2004). "Final Report of the 2003 Hurricane Season".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - World Meteorological Organization (2004). "Replacement Names for 2003 Atlantic Hurricanes (Fabian, Isabel, and Juan) and 2002 Hurricane Lili". Archived from the original (DOC) on November 9, 2004.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

- Hurricane Lili at the Wayback Machine (archived February 3, 1997) - American Red Cross