Hurricane Isabel

Hurricane Isabel was the strongest Atlantic hurricane since Mitch, and the deadliest, costliest, and most intense hurricane in the 2003 Atlantic hurricane season. Hurricane Isabel was also the strongest hurricane in the open waters of the Atlantic, both by wind speed and central pressure, before being surpassed by hurricanes Irma and Dorian in 2017 and 2019, respectively. The ninth named storm, fifth hurricane, and second major hurricane of the season, Isabel formed near the Cape Verde Islands from a tropical wave on September 6, in the tropical Atlantic Ocean. It moved northwestward, and within an environment of light wind shear and warm waters, it steadily strengthened to reach peak winds of 165 mph (270 km/h) on September 11. After fluctuating in intensity for four days, during which it displayed annular characteristics, Isabel gradually weakened and made landfall on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) on September 18. Isabel quickly weakened over land and became extratropical over western Pennsylvania on the next day. On September 20, the extratropical remnants of Isabel were absorbed into another system over Eastern Canada.

| Category 5 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Isabel at peak intensity northeast of the Leeward Islands, on September 12 | |

| Formed | September 6, 2003 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 20, 2003 |

| (Extratropical after September 19) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 165 mph (270 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 915 mbar (hPa); 27.02 inHg |

| Fatalities | 16 direct, 35 indirect |

| Damage | $3.6 billion (2003 USD) |

| Areas affected | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Greater Antilles, Turks and Caicos Islands, Bahamas, East coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada |

| Part of the 2003 Atlantic hurricane season | |

In North Carolina, the storm surge from Isabel washed out a portion of Hatteras Island to form what was unofficially known as Isabel Inlet. Damage was greatest along the Outer Banks, where thousands of homes were damaged or even destroyed. The worst of the effects of Isabel occurred in Virginia, especially in the Hampton Roads area and along the shores of rivers as far west and north as Richmond and Baltimore. Virginia reported the most deaths and damage from the hurricane. About 64% of the damage and 69% of the deaths occurred in North Carolina and Virginia. Electric service was disrupted in areas of Virginia for several days, some more rural areas were without electricity for weeks, and local flooding caused thousands of dollars in damage.

Moderate to severe damage extended up the Atlantic coastline and as far inland as West Virginia. Roughly six million people were left without electric service in the eastern United States from the strong winds of Isabel. Rainfall from the storm extended from South Carolina to Maine, and westward to Michigan. Throughout the path of Isabel, damage totalled about $5.5 billion (2003 USD). 16 deaths in seven U.S. states were directly related to the hurricane, with 35 deaths in six states and one Canadian province indirectly related to the hurricane.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

A tropical wave moved off the western coast of Africa on September 1.[1] An area of low pressure associated with the wave moved slowly westward, and its convection initially appeared to become better organized.[2] On September 3, as it passed to the south of the Cape Verde islands, organization within the system degraded,[3] though convection increased the next day.[4] The system gradually became better organized, and Dvorak classifications began early on September 5. Based on the development of a closed surface circulation, it is estimated the system developed into Tropical Depression Thirteen early on September 6. Hours later, it intensified into Tropical Storm Isabel,[1] though operationally the National Hurricane Center did not begin issuing advisories until 13 hours after it first developed.[5]

Located within an area of light wind shear and warm waters, Isabel gradually organized as curved bands developed around a circular area of deep convection near the center.[6] It steadily strengthened as it moved to the west-northwest, and Isabel strengthened to a hurricane on September 7 subsequent to the development of a large, yet ragged eye located near the deepest convection.[7] The eye, overall convective pattern, and outflow steadily improved in organization,[8] and deep convection quickly surrounded the 40-mile (60 km)-wide eye.[9] Isabel intensified on September 8 to reach major hurricane status while located 1,300 miles (2,100 km) east-northeast of Barbuda. On September 9, Isabel reached an initial peak intensity of 130 mph (210 km/h) for around 24 hours, a minimal Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale.[1]

.jpg.webp)

Early on September 10, the eyewall became less defined, the convection near the eye became eroded, and northeasterly outflow became slightly restricted.[10] As a result, Isabel weakened slightly to a Category 3 hurricane. The hurricane turned more to the west due to the influence of the Bermuda-Azores High.[1] Later on September 10, Isabel restrengthened to a Category 4 hurricane after convection deepened near the increasingly organizing eyewall.[11] The hurricane continued to intensify, and Isabel reached its peak intensity of 165 mph (270 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 915 mbar (hPa; 27.02 inHg) on September 11, a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale.[1] Due to an eyewall replacement cycle, Isabel weakened slightly, though it retained Category 5 status for 24 hours.[12] As Isabel underwent another eyewall replacement cycle, outflow degraded in appearance and convection around the eye weakened,[13] and early on September 13, Isabel weakened to a strong Category 4 hurricane. A weakness in the ridge to its north allowed the hurricane to turn to the west-northwest.[1] After completing the replacement cycle, the hurricane's large 40 mile (65 km) wide eye became better defined,[14] and late on September 13, Isabel re-attained Category 5 status.[1] During this time, Isabel attained annular characteristics, becoming highly symmetrical in shape and sporting a wide eye.[1] Hurricane Isabel also displayed a "pinwheel" eye, a rare feature that is found in some annular tropical cyclones.[15] A NOAA Hurricane Hunter Reconnaissance Aircraft flying into the hurricane launched a dropsonde which measured an instantaneous wind speed of 233 mph (375 km/h), the strongest instantaneous wind speed recorded in an Atlantic hurricane.[16] Cloud tops warmed again shortly thereafter,[17] and Isabel weakened to a strong Category 4 hurricane early on September 14. Later that day, it re-organized, and for the third time, Isabel attained Category 5 status while located 400 miles (650 km) north of San Juan, Puerto Rico.[1]

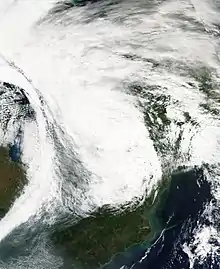

Cloud tops around the center warmed again early on September 15, and Isabel weakened to a Category 4 hurricane.[1] Later that day, the inner core of deep convection began to deteriorate, while the eye decayed in appearance. As a ridge to its northwest built southeastward, it resulted in Isabel decelerating as it turned to the north-northwest.[18] Increasing vertical wind shear contributed in weakening the hurricane further, and Isabel weakened to a Category 2 hurricane on September 16, while located 645 miles (1035 km) southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.[1] Convection remained minimal, though outflow retained excellent organization,[19] and Isabel remained a Category 2 hurricane for two days, until it made landfall between Cape Lookout and Ocracoke Island on September 18, with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h). Isabel was a large hurricane at landfall, with a windfield of 460 miles (740 kilometres).[20] The system weakened after it made landfall, though due to its fast forward motion, Isabel remained a hurricane until it reached western Virginia, early on September 19. After passing through West Virginia as a tropical storm, Isabel became extratropical over Western Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh. The system continued turned northward, and crossed Lake Erie into Canada. Early on September 20, the extratropical remnant of Isabel was absorbed by a larger extratropical storm, over the Cochrane District of Ontario.[1]

Preparations

Two days before Isabel made landfall, the National Hurricane Center issued a hurricane watch from Little River, South Carolina to Chincoteague, Virginia, including the Pamlico and Albemarle Sounds and the lower Chesapeake Bay. The NHC also issued a tropical storm watch south of Little River, South Carolina to the mouth of the Santee River, as well as from Chincoteague, Virginia northward to Little Egg Inlet, New Jersey. Hurricane and tropical storm warnings were gradually issued for portions of the East Coast of the United States. By the time Isabel made landfall, a tropical storm warning existed from Chincoteague, Virginia to Fire Island, New York and from Cape Fear, North Carolina to the mouth of the Santee River in South Carolina, and a hurricane warning existed from Chincoteague, Virginia to Cape Fear. Landfall forecasts were very accurate; from three days prior, the average track forecast error for its landfall was only 36 miles (58 km), and for 48 hours in advance the average track error was 18 miles (29 km).[1]

Officials declared mandatory evacuations for 24 counties in North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland, though in general not many left. According to a survey conducted by the United States Department of Commerce, evacuation rates were estimated as follows; 45% in the Outer Banks, 23% in the area around the Pamlico Sound, 23% in Virginia, and about 15% in Maryland.[21] The threat of Isabel resulted in the evacuation of hundreds of thousands of residents, primarily in North Carolina and Virginia, and included more than 12,000 residents staying in emergency shelters.[22]

19 major airports along the East Coast of the United States were closed, with more than 1,500 flights canceled. The Washington Metro and Metrobus system closed prior to the arrival of the storm, and Amtrak canceled nearly all trains south of the nation's capital. Schools and businesses throughout its path closed prior to Isabel's arrival to allow time to prepare; hardware and home improvement stores reported brisk business of plywood, flashlights, batteries, and portable generators, as residents prepared for the storm's potential impact. The federal government was closed excluding emergency staff members.[22] The United States Navy ordered the removal of 40 ships and submarines and dozens of aircraft from naval sites near Norfolk, Virginia.[23]

A contingency plan was established at the Tomb of the Unknowns at Arlington National Cemetery that, should the winds exceed 120 mph (190 km/h), the guards could take positions in the trophy room (above the Tomb Plaza and providing continual sight of the Tomb) but the plan was never implemented. However, it spawned an urban legend that the Third Infantry sent orders to seek shelter, orders that were deliberately disobeyed.[24]

On September 18, the Canadian Hurricane Centre issued heavy rainfall and wind warnings for portions of southern Ontario. A gale warning was also issued for Lake Ontario, eastern Lake Erie, the Saint Lawrence River and Georgian Bay.[25][26][27] A news report on September 14 warned conditions could be similar to the disaster caused by Hurricane Hazel 49 years prior, resulting in widespread media coverage on the hurricane.[28] Researchers on a Convair 580 flight studied the structure of Isabel transitioning into an extratropical storm, after two similar studies for Hurricane Michael in 2000 and Tropical Storm Karen in 2001. While flying in a thunderstorm, ice accumulation forced the plane to descend.[29]

Impact

| Region | Deaths | Damage (2003 USD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Indirect | ||

| Florida | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| North Carolina | 1 | 2 | $450 million |

| Virginia | 10 | 22 | >$1.85 billion |

| West Virginia | 0 | 0 | $20 million |

| Washington, D.C. | 0 | 1 | $125 million |

| Maryland | 1 | 6 | $820 million |

| Delaware | 0 | 0 | $40 million |

| Pennsylvania | 0 | 2 | $160 million |

| New Jersey | 1 | 1 | $50 million |

| New York | 1 | 0 | $90 million |

| Rhode Island | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ontario | 0 | 1 | Unknown |

| Total | 16 | 35 | $3.6 billion |

Strong winds from Isabel extended from North Carolina to New England and westward to West Virginia. The winds, combined with previous rainfall which moistened the soil, downed many trees and power lines across its path, leaving about 6 million electricity customers without power at some point. Parts of coastal Virginia, especially in the Hampton Roads and Northeast North Carolina areas, were without electricity for almost a month. Coastal areas suffered from waves and its powerful storm surge, with areas in eastern North Carolina and southeast Virginia reporting severe damage from both winds and the storm surge. Throughout its path, Isabel resulted in $5.5 billion in damage (2003 USD) and 51 deaths, of which 16 were directly related to the storm's effects.[30][31]

The governors of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, and Delaware declared states of emergency.[22] Isabel was the first major hurricane to threaten the Mid-Atlantic States and the Upper South since Hurricane Floyd in September 1999. Isabel's greatest effect was due to flood damage, the worst in some areas of Virginia since 1972's Hurricane Agnes. More than 60 million people were affected to some degree—a similar number to Floyd but more than any other hurricane in recent memory.[32]

Caribbean and Southeast United States

Powerful surf affected the northern coastlines of the islands in the Greater Antilles. Strong swells also lashed the Bahamas. During most hurricanes, the location of the Bahamas prevents powerful swells of Atlantic hurricanes from striking southeast Florida. However, the combination of the location, forward speed, and strength of Isabel produced strong swells through the Providence Channel onto a narrow 10 mile (16 km) stretch of the southeastern Florida coastline; wave heights peaked at 14 feet (4.3 m) at Delray Beach.[16] The swells capsized a watercraft and injured its two passengers at Boynton Beach, and a swimmer required assistance to be rescued near Juno Beach. Minor beach erosion was reported in Palm Beach County.[33] In the northern portion of the state, waves reached up to 15 feet (4.5 m) in height at Flagler Beach, causing the Flagler Beach Pier to be closed due to damaged boards from the waves.[34] Rip currents from Isabel killed a surfer at an unguarded beach in Nassau County, with an additional six people requiring rescue from the currents.[35] The beaches were later closed during the worst of the rough surf.[36]

In northeastern South Carolina, the outer rainbands produced moderate winds reaching 45 mph (72 km/h) at Myrtle Beach. Rainfall was light, peaking at 1.34 inches (34 mm) in Loris.[37]

North Carolina

Isabel produced moderate to heavy damage across eastern North Carolina, totaling $450 million (2003 USD).[1] Damage was heaviest in Dare County, where storm surge flooding and strong winds damaged thousands of houses.[38] The storm surge produced a 2,000 foot (600 m) wide inlet on Hatteras Island, unofficially known as Isabel Inlet, isolating Hatteras by road for two months.[39] Strong winds downed hundreds of trees of across the state, leaving up to 700,000 residents without power. Most areas with power outages had power restored within a few days.[38] The hurricane directly killed one person and indirectly killed two in the state.[40]

Virginia

The storm surge assailed much of southeastern Virginia causing the worst flooding seen in the area since the 1933 Chesapeake–Potomac hurricane, peaking at an estimated 9 feet (2.7 m) in Richmond along the James River. The surge caused significant damage to homes along river ways,[41] especially along the middle reaches of the James River basin.[42] The strong storm surge surpassed the floodgate to the Midtown Tunnel while workers attempted to close the gate; about 44 million US gallons (170,000 m3) of water flooded the tunnel entirely in just 40 minutes, with the workers barely able to escape.[43] The damage to the electrical grid and flooding kept Old Dominion University, Norfolk State University, Virginia Commonwealth University, University of Richmond, The College of William & Mary and many of the region's other major educational institutions closed for almost a week. Further inland, heavy rainfall was reported, peaking at 20.2 inches (513 mm) in Sherando, Virginia,[42] causing damage and severe flash flooding. Winds from the hurricane destroyed over 1,000 houses and damaged 9,000 more;[44] damage in the state totaled over $1.85 billion (2003 USD), among the costliest tropical cyclones in Virginia history.[21] The passage of Isabel also resulted in 32 deaths in the state, 10 directly from the storm's effects and 22 indirectly related.[1]

Mid-Atlantic

About 1.24 million people lost power throughout Maryland and Washington, D.C. The worst of Isabel's effects came from its storm surge, which inundated areas along the coast and resulted in severe beach erosion. In Eastern Maryland, hundreds of buildings were damaged or destroyed by the storm surge and related tidal flooding. The most severe flooding occurred in the southern portions of Dorchester and Somerset counties and on Kent Island in Queen Anne's County. Thousands of houses were affected in Central Maryland, with severe storm surge flooding reported in Baltimore and Annapolis. Washington, D.C. sustained moderate damage, primarily from the winds. Throughout Maryland and Washington, damage totaled about $945 million (2003 USD), with only one direct fatality due to flooding.[45][46][47][48]

The effects of the hurricane in Delaware were compounded by flooding caused by the remnants of Tropical Storm Henri days before.[49] Moderate winds of up to 62 mph (100 km/h) in Lewes[50] downed numerous trees, tree limbs, and power lines across the state,[51] leaving at least 15,300 without power.[52] Numerous low-lying areas were flooded due to high surf, strong storm surge, or run-off from flooding further inland.[51] The passage of Hurricane Isabel resulted in $40 million in damage (2003 USD) and no casualties in the state.[1]

Northeast United States

The winds from Isabel downed hundreds of trees and power lines across New Jersey, leaving hundreds of thousands without power; a falling tree killed one person. Rough waves and a moderate storm surge along the coastline caused moderate to severe beach erosion, and one person was killed from the rough waves. Damage in the state totaled $50 million (2003 USD).[1][53][54]

The passage of Hurricane Isabel in Pennsylvania resulted in $160 million in damage (2003 USD) and 2 indirect deaths in Pennsylvania.[1] One person suffered from carbon monoxide poisoning, believed to be caused due to improperly ventilated generators in an area affected by the power outages.[55] Moderate winds left about 1.4 million customers without power across the state as a result of trees falling into power lines, with dozens of houses and cars damaged by the trees.[56][57][58]

Damage in New York totaled $90 million (2003 USD),[1] with Vermont reporting about $100,000 in damage (2003 USD).[59][60][61][62][63][64] Falling trees from moderate winds downed power lines across the region, causing sporadic power outages. Two people died in the region as a result of the hurricane, both due to the rough surf from Isabel.[1]

Elsewhere

In West Virginia, the storm produced moderate rainfall across the state that peaked at 6.88 in (175 mm) near Sugar Grove.[65] The rainfall resulted in mudslides and flash flooding, covering several roads and washing away two bridges. The South Branch Potomac River crested at 24.7 feet (7.5 m), 9.3 feet (2.8 m) above flood state near Springfield. The flooding broke a levee at Michael Field, and in Mineral County one school and 14 basements were flooded. In Jefferson County, two people required rescue after a car drove into floodwaters.[66] Although sustained winds were weak in the state, wind gusts reached 46 mph (74 km/h) at Martinsburg. With the wet grounds, the wind gusts toppled thousands of trees, which fell onto homes, roads, and power lines.[66] About 1.4 million residents across the state were left without power.[67] Damage in the state totaled $20 million (2003 USD). No deaths were reported,[1] and three were injured from the hurricane.[66]

Isabel dropped light to moderate precipitation across the eastern half of Ohio, with isolated locations reporting over 3 in (75 mm).[42] Moisture from Isabel dropped light rainfall across eastern Michigan and peaked at 1.55 inches (39 mm) at Mount Clemens. Additionally, Doppler weather radar estimated rainfall approached 2.5 inches (64 mm) in St. Clair County. No damage was reported from Isabel in the region.[68]

Swells from Isabel produced moderate surf along the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia, particularly in the Gulf of Maine.[25] Isabel also produced rough surf in Lake Ontario, with waves reaching 4 m (13 ft) along the western portion. At Hamilton, the waves surpassed seawalls and produced spray onto coastal streets.[29] Rainfall peaked at 59 mm (2.3 in), which caused minor flooding and led to one traffic fatality. About 27,000 people lost power, mostly near Toronto.[69] The strong pressure gradient between Isabel and a high pressure system over eastern Canada produced strong easterly winds across lakes Ontario and Erie.[29] A buoy in Lake Ontario reported a peak gust of 78 km/h (49 mph),[70] and gusts reached as strong as 81 km/h (51 mph) at Port Colborne, Ontario.[1]

Aftermath

By about a week after the passage of the hurricane, President George W. Bush declared disaster areas for 36 North Carolina counties, 77 counties and independent cities in Virginia, the entire state of Maryland, all three counties in Delaware and six West Virginia counties. The disaster declaration allocated the use of federal funds for rebuilding and providing aid in the aftermath of hurricane Isabel.[21] By about four months after the passage of the hurricane, disaster aid totaled about $516 million (2003 USD), primarily in North Carolina and Virginia. Over 166,000 residents applied for individual assistance, with about $117 million (2003 USD) approved for residents to assist with temporary housing and home repairs. About 50,000 business owners applied for Small Business Administration loans, with about $178 million (2003 USD) approved for the assistance loans. About 40,000 people visited local disaster recovery centers, designed to provide additional information regarding the aftermath of the hurricane.[71][72][73][74][75]

In North Carolina, hundreds of residents were stranded in Hatteras following the formation of Isabel Inlet.[76] People who were not residents were not allowed to be on the Outer Banks for two weeks after the hurricane due to damaged road conditions. When visitors were allowed to return, many ventured to see the new inlet, despite a 1-mile (1.6-km) walk from the nearest road.[39] Initially, long-term solutions to the Isabel Inlet such as building a bridge or a ferry system were considered, though they were ultimately canceled in favor of pumping sand and filling the inlet. Coastal geologists were opposed to the solution, stating the evolution of the Outer Banks is dependent on inlets from hurricanes.[77] Dredging operations began on October 17, about a month after the hurricane struck. The United States Geological Survey used sand from the ferry channel to the southwest of Hatteras Island, a choice made to minimize the impact to submerged aquatic vegetation and due to the channel being filled somewhat during the hurricane.[78] On November 22, about two months after the hurricane struck, North Carolina Highway 12 and Hatteras Island were reopened to public access. On the same day, the ferry between Hatteras and Ocracoke was reopened.[39]

In West Virginia, the power outages were restored within a week.[79] Power workers throughout Canada assisted the severely affected power companies from Maryland to North Carolina.[80] Hydro-Québec sent 25 teams to the New York City area to assist in power outages.[81]

Retirement

Because of widespread property damage and extensive death tolls the name Isabel was retired after the 2003 season, and will not be used for future Atlantic hurricanes. It was replaced by Ida for the naming list for the 2009 season.[82] The names Ina and Ivy were also suggested as possible replacement names.[83]

See also

- Other storms of the same name

- 1933 Chesapeake–Potomac hurricane

- Annular hurricane

- Hurricane Fran

- Hurricane Ernesto (2006)

- Hurricane Hazel

- Hurricane Hugo

- Hurricane Irene

- Hurricane Irma

- Hurricane Isaias

- Hurricane Sandy

- Hurricane Florence

- Tropical Storm Josephine (2020), a 2020 tropical storm that took a similar path north of the Lesser Antilles

- List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- List of North Carolina hurricanes (2000–present)

- Timeline of the 2003 Atlantic hurricane season

References

- Jack Beven; Hugh Cobb (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- Franklin (2003). "September 2 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 2011-02-17. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- Avila (2003). "September 3 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 2011-02-17. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- Pasch (2003). "September 4 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 2011-02-17. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- Avila (2003). "Tropical Storm Isabel Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- Avila (2003). "Tropical Storm Isabel Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- Stewart (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Six". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- Stewart (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Seven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- Jarvinen (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Eight". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- Franklin (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Sixteen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- Stewart (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Nineteen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- Beven (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Twenty-Six". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- Franklin (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Twenty-Eight". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- Stewart (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Thirty". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- Montgomery, Michael T. (2014). Advances in Tropical Cyclone Research: Chapter 21: Introduction to Hurricane Dynamics: Tropical Cyclone Intensification (PDF). Naval Postgraduate School. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Richard J. David; Charles H. Paxton (2005). "How the Swells of Hurricane Isabel Impacted Southeast Florida". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 86 (8): 1065–1068. Bibcode:2005BAMS...86.1065D. doi:10.1175/BAMS-86-8-1065.

- Lawrence (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Thirty-Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- Franklin (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Thirty-Eight". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- Avila & Pasch (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Discussion Forty-Eight". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- "Hurricane ISABEL". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2019-08-28.

- Post, Buckley, Schuh and Jernigan (2005). "Hurricane Isabel Assessment, a Review of Hurricane Evacuation Study Products and Other Aspects of the National Hurricane Mitigation and Preparedness Program (NHMPP) in the Context of the Hurricane Isabel Response" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Scotsman.com (2003-09-19). "America feels the wrath of Isabel". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- CNN.com (2003-09-15). "Storm could cause 'extensive damage'". Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- "The Unknown Soldiers". 24 September 2003.

- Forgarty, Szeto, and LaFortune (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Information Statement on September 18, 2003". Canadian Hurricane Centre. Archived from the original on November 20, 2013. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Parkes (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Information Statement on September 19, 2003". Canadian Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on November 20, 2013. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- Parkes and McIldoon (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Information Statement on September 19, 2003 (2)". Canadian Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on November 20, 2013. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- Canadian Hurricane Centre (2004). "2003 Tropical Cyclone Season Summary". Archived from the original on 2007-02-02. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- Chris Fogarty (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Summary in Canada". Canadian Hurricane Centre. Archived from the original on 2006-10-26. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables updated (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- United States Department of Commerce (2004). "Service Assessment of Hurricane Isabel" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Climate of 2003- Comparison of Hurricanes Floyd, Hugo and Isabel". Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Florida". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Florida (2)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Florida (3)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Florida (4)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- Wilmington, North Carolina National Weather Service (2003). "Hurricane Isabel in South Carolina". Archived from the original on 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for North Carolina". Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- Fred Hurteau (2003). "The Dynamic Landscape of the Outer Banks". Outer Banks Guidebook. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- Sunbelt Rentals (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Aftermath" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 2, 2007. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- United States Department of Commerce (2004). "Service Assessment of Hurricane Isabel" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- David Roth (2005). "Rainfall Summary for Hurricane Isabel". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- Sunbelt Rentals (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Effects by Region" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 2, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Virginia". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Eastern Maryland". Archived from the original on May 24, 2007. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- NCDC (2003). "Event Report for Central Maryland". Archived from the original on May 24, 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Western Maryland". Archived from the original on May 24, 2007. Retrieved 2006-12-28.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Washington, D.C." Archived from the original on May 24, 2007. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- FEMA (2003). "Disaster Recovery Centers to Open". Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- Gorse & Frugis (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Post Tropical Storm Report". Mount Holly, New Jersey National Weather Service. Archived from the original (TXT) on 2005-03-19. Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Delaware". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- Joint Information Center (2003). "Sporadic Power Outages Being Reported Across State" (PDF). Delaware Emergency Management Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 18, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for New Jersey". Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved 2006-11-15.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (2003). "Coastal Storm Survey" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-12. Retrieved 2006-11-15.

- CNN (2003-09-22). "Isabel death toll creeps higher". Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Southeast Pennsylvania". Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Central Pennsylvania". Archived from the original on January 27, 2008. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- State College, Pennsylvania National Weather Service (2003). "Hurricane Isabel: September 2003". Archived from the original on 2005-04-04. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Vermont". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Vermont (2)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Vermont (3)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Vermont (4)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Vermont (5)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Vermont (6)". Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved 2007-01-31.

- Roth, David M; Weather Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- National Climatic Data Center (2003). "Event Report for Hurricane Isabel". Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- United States Department of Commerce (2004). "Service Assessment of Hurricane Isabel" (PDF). NOAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- Detroit National Weather Service (2003). "Remnants of Isabel Bring Rainfall to Southeast Michigan Friday Morning". Retrieved 2007-02-08.

- 2003-Isabel (Report). Environment Canada. 2010-09-14. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- Szeto and LaFortune (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Information Statement on September 20, 2003". Canadian Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on November 20, 2013. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- FEMA (2003). "State/Federal Disaster Aid Tops $155 Million in North Carolina". Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- FEMA (2004). "Commonwealth of Virginia Receives Nearly $257 Million In Disaster Assistance". Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- FEMA (2003). "Maryland Disaster Aid Nearing $100 Million". Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- FEMA (2003). "Disaster Victims in Delaware Receive Over $3.5 Million In Assistance So Far". Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- FEMA (2003). "Disaster Aid in Pennsylvania Surpasses Half Million Dollars". Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- Sunbelt Rentals (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Aftermath" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 2, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- John Roach (2003). "Shoring Up N. Carolina Islands: A Losing Battle?". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (2003). "Dredging Operations Begin". Archived from the original on October 6, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- United States Department of Energy (2003). "Hurricane Isabel Situation Report: September 25, 2003" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-02. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- Constellation Energy (2003). "The Facts: Hurricane Isabel and BGE" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- CBC News (September 18, 2003). "Isabel to bring heavy winds to eastern Ontario". Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved 2007-02-04.

- World Meteorological Organization (2004). "Final Report of the 2003 Hurricane Season" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- World Meteorological Organization (2004). "Replacement Names for 2003 Atlantic Hurricanes (Fabian, Isabel, and Juan) and 2002 Hurricane Lili" (DOC). Retrieved 2007-02-11.

External links

- National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report for Hurricane Isabel

- National Hurricane Center advisory archive for Hurricane Isabel

- National Weather Service Assessment

- Category 5 Hurricane Isabel eye vortices java loop, Interpretation of

- Hurricane Isabel in Perspective: Proceedings of a Conference