Jomo Kenyatta

Jomo Kenyatta[lower-alpha 1] CGH (c. 1897 – 22 August 1978) was a Kenyan anti-colonial activist and politician who governed Kenya as its Prime Minister from 1963 to 1964 and then as its first President from 1964 to his death in 1978. He was the country's first indigenous head of government and played a significant role in the transformation of Kenya from a colony of the British Empire into an independent republic. Ideologically an African nationalist and conservative, he led the Kenya African National Union (KANU) party from 1961 until his death.

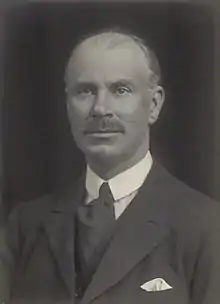

Jomo Kenyatta CGH | |

|---|---|

President Kenyatta in 1966 | |

| 1st President of Kenya | |

| In office 12 December 1964 – 22 August 1978 | |

| Vice President | Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Joseph Murumbi Daniel arap Moi |

| Preceded by | Elizabeth II as Queen of Kenya |

| Succeeded by | Daniel arap Moi |

| 1st Prime Minister of Kenya | |

| In office 1 June 1963 – 12 December 1964 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Succeeded by | Raila Odinga (2008) |

| Chairman of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) | |

| In office 1961–1978 | |

| Preceded by | James Gichuru |

| Succeeded by | Daniel arap Moi |

| Member of Parliament for the Gatundu Constituency | |

| In office 1963–1978 | |

| Preceded by | established |

| Succeeded by | Ngengi Wa Muigai |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Kamau wa Muigai c. 1897 Nginda, British East Africa |

| Died | 22 August 1978 (aged 80–81) Mombasa, Coast Province, Kenya |

| Resting place | Parliament Buildings, Nairobi, Kenya |

| Nationality | Kenyan |

| Political party | KANU |

| Spouse(s) | Grace Wahu (m. 1919) Edna Clarke (1942–1946) Grace Wanjiku (d. 1950) Ngina Kenyatta (m. 1951) |

| Children | 8

|

| Alma mater | University College London, London School of Economics |

| Notable work(s) | Facing Mount Kenya |

| Signature | |

Kenyatta was born to Kikuyu farmers in Kiambu, British East Africa. Educated at a mission school, he worked in various jobs before becoming politically engaged through the Kikuyu Central Association. In 1929, he travelled to London to lobby for Kikuyu land affairs. During the 1930s, he studied at Moscow's Communist University of the Toilers of the East, University College London, and the London School of Economics. In 1938, he published an anthropological study of Kikuyu life before working as a farm labourer in Sussex during the Second World War. Influenced by his friend George Padmore, he embraced anti-colonialist and Pan-African ideas, co-organising the 1945 Pan-African Congress in Manchester. He returned to Kenya in 1946 and became a school principal. In 1947, he was elected President of the Kenya African Union, through which he lobbied for independence from British colonial rule, attracting widespread indigenous support but animosity from white settlers. In 1952, he was among the Kapenguria Six arrested and charged with masterminding the anti-colonial Mau Mau Uprising. Although protesting his innocence—a view shared by later historians—he was convicted. He remained imprisoned at Lokitaung until 1959 and was then exiled to Lodwar until 1961.

On his release, Kenyatta became President of KANU and led the party to victory in the 1963 general election. As Prime Minister, he oversaw the transition of the Kenya Colony into an independent republic, of which he became president in 1964. Desiring a one-party state, he transferred regional powers to his central government, suppressed political dissent, and prohibited KANU's only rival—Oginga Odinga's leftist Kenya People's Union—from competing in elections. He promoted reconciliation between the country's indigenous ethnic groups and its European minority, although his relations with the Kenyan Indians were strained and Kenya's army clashed with Somali separatists in the North Eastern Province during the Shifta War. His government pursued capitalist economic policies and the "Africanisation" of the economy, prohibiting non-citizens from controlling key industries. Education and healthcare were expanded, while UK-funded land redistribution favoured KANU loyalists and exacerbated ethnic tensions. Under Kenyatta, Kenya joined the Organisation of African Unity and the Commonwealth of Nations, espousing a pro-Western and anti-communist foreign policy amid the Cold War. Kenyatta died in office and was succeeded by Daniel arap Moi.

Kenyatta was a controversial figure. Prior to Kenyan independence, many of its white settlers regarded him as an agitator and malcontent, although across Africa he gained widespread respect as an anti-colonialist. During his presidency, he was given the honorary title of Mzee and lauded as the Father of the Nation, securing support from both the black majority and the white minority with his message of reconciliation. Conversely, his rule was criticised as dictatorial, authoritarian, and neocolonial, of favouring Kikuyu over other ethnic groups, and of facilitating the growth of widespread corruption.

Early life

Childhood

A member of the Kikuyu people, Kenyatta was born with the name Kamau in the village of Nginda.[2] Birth records were not then kept among the Kikuyu, and Kenyatta's date of birth is not known.[3] One biographer, Jules Archer, suggested he was likely born in 1890,[4] although a fuller analysis by Jeremy Murray-Brown suggested a birth circa 1897 or 1898.[5] Kenyatta's father was named Muigai, and his mother Wambui.[2] They lived in a homestead near the River Thiririka, where they raised crops, bred sheep and goats.[2] Muigai was sufficiently wealthy that he could afford to keep several wives, each living in a separate nyūmba (woman's hut).[6]

Kenyatta was raised according to traditional Kikuyu custom and belief, and was taught the skills needed to herd the family flock.[7] When he was ten, his earlobes were pierced to mark his transition from childhood.[8] Wambui subsequently bore another son, Kongo,[9] shortly before Muigai died.[10] In keeping with Kikuyu tradition, Wambui then married her late husband's younger brother, Ngengi.[10] Kenyatta then took the name of Kamau wa Ngengi ("Kamau, son of Ngengi").[11] Wambui bore her new husband a son, whom they also named Muigai.[10] Ngengi was harsh and resentful toward the three boys, and Wambui decided to take her youngest son to live with her parental family further north.[10] It was there that she died, and Kenyatta—who was very fond of the younger Muigai—travelled to collect his infant half-brother.[10] Kenyatta then moved in with his grandfather, Kongo wa Magana, and assisted the latter in his role as a traditional healer.[12]

"Missionaries have done a lot of good work because it was through the missionary that many of the Kikuyu got their first education ... and were able to learn how to read and write ... Also, the medical side of it: the missionary did very well. At the same time I think the missionaries ... did not understand the value of the African custom, and many of them tried to stamp out some of the customs without knowing the part they play in the life of the Kikuyu ... They upset the life of the people."

—Kenyatta, in a BBC interview, 1963[13]

In November 1909, Kenyatta left home and enrolled as a pupil at the Church of Scotland Mission (CSM) at Thogoto.[14] The missionaries were zealous Christians who believed that bringing Christianity to the indigenous peoples of Eastern Africa was part of Britain's civilizing mission.[15] While there, Kenyatta stayed at the small boarding school, where he learnt stories from the Bible,[16] and was taught to read and write in English.[17] He also performed chores for the mission, including washing the dishes and weeding the gardens.[18] He was soon joined at the mission dormitory by his brother Kongo.[19] The longer the pupils stayed, the more they came to resent the patronising way many of the British missionaries treated them.[20]

Kenyatta's academic progress was unremarkable, and in July 1912 he became an apprentice to the mission's carpenter.[21] That year, he professed his dedication to Christianity and began undergoing catechism.[21] In 1913, he underwent the Kikuyu circumcision ritual; the missionaries generally disapproved of this custom, but it was an important aspect of Kikuyu tradition, allowing Kenyatta to be recognized as an adult.[22] Asked to take a Christian name for his upcoming baptism, he first chose both John and Peter after Jesus' apostles. Forced by the missionaries to choose just one, he chose Johnstone, the -stone chosen as a reference to Peter.[23] Accordingly, he was baptized as Johnstone Kamau in August 1914.[24] After his baptism, Kenyatta moved out of the mission dormitory and lived with friends.[25] Having completed his apprenticeship to the carpenter, Kenyatta requested that the mission allow him to be an apprentice stonemason, but they refused.[25] He then requested that the mission recommend him for employment, but the head missionary refused because of an allegation of minor dishonesty.[26]

Nairobi: 1914–1922

Kenyatta moved to Thika, where he worked for an engineering firm run by the Briton John Cook. In this position, he was tasked with fetching the company wages from a bank in Nairobi, 25 miles (40 km) away.[27] Kenyatta left the job when he became seriously ill; he recuperated at a friend's house in the Tumutumu Presbyterian mission.[28] At the time, the British Empire was engaged in the First World War, and the British Army had recruited many Kikuyu. One of those who joined was Kongo, who disappeared during the conflict; his family never learned of his fate.[29] Kenyatta did not join the armed forces, and like other Kikuyu he moved to live among the Maasai, who had refused to fight for the British.[30] Kenyatta lived with the family of an aunt who had married a Maasai chief,[31] adopting Maasai customs and wearing Maasai jewellery, including a beaded belt known as kinyata in the Kikuyu language. At some point, he took to calling himself "Kinyata" or "Kenyatta" after this garment.[32]

In 1917, Kenyatta moved to Narok, where he was involved in transporting livestock to Nairobi,[31] before relocating to Nairobi to work in a store selling farming and engineering equipment.[31] In the evenings, he took classes in a church mission school.[31] Several months later he returned to Thika before obtaining employment building houses for the Thogota Mission.[33] He also lived for a time in Dagoretti, where he became a retainer for a local sub-chief, Kioi; in 1919 he assisted Kioi in putting the latter's case in a land dispute before a Nairobi court.[34] Desiring a wife,[35] Kenyatta entered a relationship with Grace Wahu, who had attended the CMS School in Kabete; she initially moved into Kenyatta's family homestead,[35] although she joined Kenyatta in Dagoretti when Ngengi drove her out.[35] On 20 November 1920 she gave birth to Kenyatta's son, Peter Muigui.[36] In October 1920, Kenyatta was called before the Thogota Kirk Session and suspended from taking Holy Communion; the suspension was in response to his drinking and his relations with Wahu out of wedlock.[37] The church insisted that a traditional Kikuyu wedding would be inadequate, and that he must undergo a Christian marriage;[38] this took place on 8 November 1922.[39] Kenyatta had initially refused to cease drinking,[38] but in July 1923 officially renounced alcohol and was allowed to return to Holy Communion.[40]

In April 1922, Kenyatta began working as a stores clerk and meter reader for Cook, who had been appointed water superintendent for Nairobi's municipal council.[41] He earned 250/= (£12/10/–, equivalent to £726 in 2021) a month, a particularly high wage for a native African, which brought him financial independence and a growing sense of self-confidence.[42] Kenyatta lived in the Kilimani neighbourhood of Nairobi,[43] although he financed the construction of a second home at Dagoretti; he referred to this latter hut as the Kinyata Stores for he used it to hold general provisions for the neighborhood.[44] He had sufficient funds that he could lend money to European clerks in the offices,[45] and could enjoy the lifestyle offered by Nairobi, which included cinemas, football matches, and imported British fashions.[45]

Kikuyu Central Association: 1922–1929

Anti-imperialist sentiment was on the rise among both native and Indian communities in Kenya following the Irish War of Independence and the Russian October Revolution.[46] Many indigenous Africans resented having to carry kipande identity certificates at all times, being forbidden from growing coffee, and paying taxes without political representation.[47] Political upheavals occurred in Kikuyuland—the area inhabited largely by the Kikuyu—following World War I, among them the campaigns of Harry Thuku and the East African Association, resulting in the government massacre of 21 native protesters in March 1922.[48] Kenyatta had not taken part in these events,[49] perhaps so as not to disrupt his lucrative employment prospects.[43]

Kenyatta's interest in politics stemmed from his friendship with James Beauttah, a senior figure in the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA). Beauttah took Kenyatta to a political meeting in Pumwani, although this led to no firm involvement at the time.[50] In either 1925 or early 1926, Beauttah moved to Uganda, but remained in contact with Kenyatta.[46] When the KCA wrote to Beauttah and asked him to travel to London as their representative, he declined, but recommended that Kenyatta—who had a good command of English—go in his place.[51] Kenyatta accepted, probably on the condition that the Association matched his pre-existing wage.[52] He thus became the group's secretary.[53]

It is likely that the KCA purchased a motorbike for Kenyatta,[52] which he used to travel around Kikuyuland and neighbouring areas inhabited by the Meru and Embu, helping to establish new KCA branches.[54] In February 1928, he was part of a KCA party that visited Government House in Nairobi to give evidence in front of the Hilton Young Commission, which was then considering a federation between Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika.[55] In June, he was part of a KCA team which appeared before a select committee of the Kenyan Legislative Council to express concerns about the recent introduction of Land Boards. Introduced by the British Governor of Kenya, Edward Grigg, these Land Boards would hold all land in native reserves in trust for each tribal group. Both the KCA and the Kikuyu Association opposed these Land Boards, which treated Kikuyu land as collectively-owned rather than recognising individual Kikuyu land ownership.[56] Also in February, his daughter, Wambui Margaret, was born.[57] By this point he was increasingly using the name "Kenyatta", which had a more African appearance than "Johnstone".[58]

In May 1928, the KCA launched a Kikuyu-language magazine, Muĩgwithania (roughly translated as "The Reconciler" or "The Unifier"), in which it published news, articles, and homilies.[59] Its purpose was to help unify the Kikuyu and raise funds for the KCA.[60] Kenyatta was listed as the publication's editor,[58] although Murray-Brown suggested that he was not the guiding hand behind it and that his duties were largely confined to translating into Kikuyu.[60] Aware that Thuku had been exiled for his activism, Kenyatta's took a cautious approach to campaigning, and in Muĩgwithania he expressed support for the churches, district commissioners, and chiefs.[61] He also praised the British Empire, stating that: "The first thing [about the Empire] is that all people are governed justly, big or small—equally. The second thing is that nobody is regarded as a slave, everyone is free to do what he or she likes without being hindered."[60] This did not prevent Grigg from writing to the authorities in London requesting permission to shut the magazine down.[57]

Overseas

London: 1929–1931

After the KCA raised sufficient funds, in February 1929 Kenyatta sailed from Mombasa to Britain.[62] Grigg's administration could not stop Kenyatta's journey but asked London's Colonial Office not to meet with him.[63] He initially stayed at the West African Students' Union premises in West London, where he met Ladipo Solanke.[64] He then lodged with a prostitute; both this and Kenyatta's lavish spending brought concern from the Church Mission Society.[65] His landlord subsequently impounded his belongings due to unpaid debt.[66] In the city, Kenyatta met with W. McGregor Ross at the Royal Empire Society, Ross briefing him on how to deal with the Colonial Office.[67] Kenyatta became friends with Ross' family, and accompanied them to social events in Hampstead.[68] He also contacted anti-imperialists active in Britain, including the League Against Imperialism, Fenner Brockway, and Kingsley Martin.[69] Grigg was in London at the same time and, despite his opposition to Kenyatta's visit, agreed to meet with him at the Rhodes Trust headquarters in April. At the meeting, Kenyatta raised the land issue and Thuku's exile, the atmosphere between the two being friendly.[70] In spite of this, following the meeting, Grigg convinced Special Branch to monitor Kenyatta.[71]

Kenyatta developed contacts with radicals to the left of the Labour Party, including several communists.[72] In the summer of 1929, he left London and traveled by Berlin to Moscow before returning to London in October.[73] Kenyatta was strongly influenced by his time in the Soviet Union.[74] Back in England, he wrote three articles on the Kenyan situation for the Communist Party of Great Britain's newspapers, the Daily Worker and Sunday Worker. In these, his criticism of British imperialism was far stronger than it had been in Muĩgwithania.[75] These communist links concerned many of Kenyatta's liberal patrons.[72] In January, Kenyatta met with Drummond Shiels, the Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, at the House of Commons. Kenyatta told Shiels that he was not affiliated with communist circles and was unaware of the nature of the newspaper which published his articles.[76] Shiels advised Kenyatta to return home to promote Kikuyu involvement in the constitutional process and discourage violence and extremism.[77] After eighteen months in Europe, Kenyatta had run out of money. The Anti-Slavery Society advanced him funds to pay off his debts and return to Kenya.[78] Although Kenyatta enjoyed life in London and feared arrest if he returned home,[79] he sailed back to Mombasa in September 1930.[80] On his return, his prestige among the Kikuyu was high because of his time spent in Europe.[81]

In his absence, female genital mutilation (FGM) had become a topic of strong debate in Kikuyu society. The Protestant churches, backed by European medics and the colonial authorities, supported the abolition of this traditional practice, but the KCA rallied to its defence, claiming that its abolition would damage the structure of Kikuyu society.[82] Anger between the two sides had heightened, several churches expelling KCA members from their congregations, and it was widely believed that the January 1930 killing of an American missionary, Hulda Stumpf, had been due to the issue.[83] As Secretary of the KCA, Kenyatta met with church representatives. He expressed the view that although personally opposing FGM, he regarded its legal abolition as counter-productive, and argued that the churches should focus on eradicating the practice through educating people about its harmful effects on women's health.[84] The meeting ended without compromise, and John Arthur—the head of the Church of Scotland in Kenya—later expelled Kenyatta from the church, citing what he deemed dishonesty during the debate.[85] In 1931, Kenyatta took his son out of the church school at Thogota and enrolled him in a KCA-approved, independent school.[86]

Return to Europe: 1931–1933

"With the support of all revolutionary workers and peasants we must redouble our efforts to break the bonds that bind us. We must refuse to give any support to the British imperialists either by paying taxes or obeying any of their slave laws! We can fight in unity with the workers and toilers of the whole world, and for a Free Africa."

—Kenyatta in the Labour Monthly, November 1933[87]

In May 1931, Kenyatta and Parmenas Mockerie sailed for Britain, intent on representing the KCA at a Joint Committee of Parliament on the future of East Africa.[88] Kenyatta would not return to Kenya for fifteen years.[89] In Britain, he spent the summer attending an Independent Labour Party summer school and Fabian Society gatherings.[90] In June, he visited Geneva, Switzerland to attend a Save the Children conference on African children.[91] In November, he met the Indian independence leader Mohandas Gandhi while in London.[92] That month, he enrolled in the Woodbrooke Quaker College in Birmingham, where he remained until the spring of 1932, attaining a certificate in English writing.[93]

In Britain, Kenyatta befriended an Afro-Caribbean Marxist, George Padmore, who was working for the Soviet-run Comintern.[94] Over time, he became Padmore's protégé.[95] In late 1932, he joined Padmore in Germany.[96] Before the end of the year, the duo relocated to Moscow, where Kenyatta studied at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East.[97] There he was taught arithmetic, geography, natural science, and political economy, as well as Marxist-Leninist doctrine and the history of the Marxist-Leninist movement.[98] Many Africans and members of the African diaspora were attracted to the institution because it offered free education and the opportunity to study in an environment where they were treated with dignity, free from the institutionalised racism present in the U.S. and British Empire.[99] Kenyatta complained about the food, accommodation, and poor quality of English instruction.[72] There is no evidence that he joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union,[100] and one of his fellow students later characterised him as "the biggest reactionary I have ever met."[101] Kenyatta also visited Siberia, probably as part of an official guided tour.[102]

The emergence of Germany's Nazi government shifted political allegiances in Europe; the Soviet Union pursued formal alliances with France and Czechoslovakia,[103] and thus reduced its support for the movement against British and French colonial rule in Africa.[104] As a result, Comintern disbanded the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers, with which both Padmore and Kenyatta were affiliated. Padmore resigned from the Soviet Communist Party in protest, and was subsequently vilified in the Soviet press.[105] Both Padmore and Kenyatta left the Soviet Union, the latter returning to London in August 1933.[106] The British authorities were highly suspicious of Kenyatta's time in the Soviet Union, suspecting that he was a Marxist-Leninist, and following his return the MI5 intelligence service intercepted and read all his mail.[107]

Kenyatta continued writing articles, reflecting Padmore's influence.[108] Between 1931 and 1937 he wrote several articles for the Negro Worker and joined the newspaper's editorial board in 1933.[109] He also produced an article for a November 1933 issue of Labour Monthly,[110] and in May 1934 had a letter published in The Manchester Guardian.[111] He also wrote the entry on Kenya for Negro, an anthology edited by Nancy Cunard and published in 1934.[112] In these, he took a more radical position than he had in the past, calling for complete self-rule in Kenya.[113] In doing so he was virtually alone among political Kenyans; figures like Thuku and Jesse Kariuki were far more moderate in their demands.[114] The pro-independence sentiments that he was able to express in Britain would not have been permitted in Kenya itself.[87]

University College London and the London School of Economics: 1933–1939

Between 1935 and 1937, Kenyatta worked as a linguistic informant for the Phonetics Department at University College London (UCL); his Kikuyu voice recordings assisted Lilias Armstrong's production of The Phonetic and Tonal Structure of Kikuyu.[115] The book was published under Armstrong's name, although Kenyatta claimed he should have been listed as co-author.[116] He enrolled at UCL as a student, studying an English course between January and July 1935 and then a phonetics course from October 1935 to June 1936.[117] Enabled by a grant from the International African Institute,[118] he also took a social anthropology course under Bronisław Malinowski at the London School of Economics (LSE). Kenyatta lacked the qualifications normally required to join the course, but Malinowski was keen to support the participation of indigenous peoples in anthropological research.[119] For Kenyatta, acquiring an advanced degree would bolster his status among Kenyans and display his intellectual equality with white Europeans in Kenya.[120] Over the course of his studies, Kenyatta and Malinowski became close friends.[121] Fellow course-mates included the anthropologists Audrey Richards, Lucy Mair, and Elspeth Huxley.[122] Another of his fellow LSE students was Prince Peter of Greece and Denmark, who invited Kenyatta to stay with him and his mother, Princess Marie Bonaparte, in Paris during the spring of 1936.[123]

.jpg.webp)

Kenyatta returned to his former dwellings at 95 Cambridge Street,[124] but did not pay his landlady for over a year, owing over £100 in rent.[125] This angered Ross and contributed to the breakdown of their friendship.[126] He then rented a Camden Town flat with his friend Dinah Stock, whom he met at an anti-imperialist rally in Trafalgar Square.[127] Kenyatta socialised at the Student Movement House in Russell Square, which he had joined in the spring of 1934,[128] and befriended Africans in the city.[129] To earn money, he worked as one of 250 black extras in the film Sanders of the River, filmed at Shepperton Studios in Autumn 1934.[129] Several other Africans in London criticized him for doing so, arguing that the film degraded black people.[130] Appearing in the film also allowed him to meet and befriend its star, the African-American Paul Robeson.[131]

In 1935, Italy invaded Ethiopia (Abyssinia), incensing Kenyatta and other Africans in London; he became the honorary secretary of the International African Friends of Abyssinia, a group established by Padmore and C. L. R. James.[132] When Ethiopia's monarch Haile Selassie fled to London in exile, Kenyatta personally welcomed him at Waterloo station.[133] This group developed into a wider pan-Africanist organisation, the International African Service Bureau (IASB), of which Kenyatta became one of the vice chairs.[134] Kenyatta began giving anti-colonial lectures across Britain for groups like the IASB, the Workers' Educational Association, Indian National Congress of Great Britain, and the League of Coloured Peoples.[135] In October 1938, he gave a talk to the Manchester Fabian Society in which he described British colonial policy as fascism and compared the treatment of indigenous people in East Africa to the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany.[136] In response to these activities, the British Colonial Office reopened their file on him, although could not find any evidence that he was engaged in anything sufficiently seditious to warrant prosecution.[137]

Kenyatta assembled the essays on Kikuyu society written for Malinowski's class and published them as Facing Mount Kenya in 1938.[138] Featuring an introduction written by Malinowski,[139] the book reflected Kenyatta's desire to use anthropology as a weapon against colonialism.[122] In it, Kenyatta challenged the Eurocentric view of history by presenting an image of a golden African past by emphasising the perceived order, virtue, and self-sufficiency of Kikuyu society.[140] Utilising a functionalist framework,[141] he promoted the idea that traditional Kikuyu society had a cohesion and integrity that was better than anything offered by European colonialism.[142] In this book, Kenyatta made clear his belief that the rights of the individual should be downgraded in favour of the interests of the group.[143] The book also reflected his changing views on female genital mutilation; where once he opposed it, he now unequivocally supported the practice, downplaying the medical dangers that it posed to women.[144]

The book's jacket cover featured an image of Kenyatta in traditional dress, wearing a skin cloak over one shoulder and carrying a spear.[145] The book was published under the name "Jomo Kenyatta", the first time that he had done so; the term Jomo was close to a Kikuyu word describing the removal of a sword from its scabbard.[146] Facing Mount Kenya was a commercial failure, selling only 517 copies, but was generally well received;[147] an exception was among white Kenyans, whose assumptions about the Kikuyu being primitive savages in need of European civilization it challenged.[148] Murray-Brown later described it as "a propaganda tour de force. No other African had made such an uncompromising stand for tribal integrity."[149] Bodil Folke Frederiksen, a scholar of development studies, referred to it as "probably the most well-known and influential African scholarly work of its time",[150] while for fellow scholar Simon Gikandi, it was "one of the major texts in what has come to be known as the invention of tradition in colonial Africa".[151]

World War II: 1939–1945

"In the last war 300,000 of my people fought in the British Army to drive the Germans from East Africa and 60,000 of them lost their lives. In this war large numbers of my people have been fighting to smash fascist power in Africa and have borne some of the hardest fights against the Italians. Surely if we are considered fit enough to take our rifles and fight side by side with white men we have a right to a direct say in the running of our country and to education."

—Kenyatta, during World War II[152]

After the United Kingdom entered World War II in September 1939, Kenyatta and Stock moved to the Sussex village of Storrington.[153] Kenyatta remained there for the duration of the war, renting a flat and a small plot of land to grow vegetables and raise chickens.[154] He settled into rural Sussex life,[155] and became a regular at the village pub, where he gained the nickname "Jumbo".[156] In August 1940, he took a job at a local farm as an agricultural worker—allowing him to evade military conscription—before working in the tomato greenhouses at Lindfield.[157] He attempted to join the local Home Guard, but was turned down.[152] On 11 May 1942 he married an English woman, Edna Grace Clarke, at Chanctonbury Registry Office.[158] In August 1943, their son, Peter Magana, was born.[158]

Intelligence services continued monitoring Kenyatta, noting that he was politically inactive between 1939 and 1944.[159] In Sussex, he wrote an essay for the United Society for Christian Literature, My People of Kikuyu and the Life of Chief Wangombe, in which he called for his tribe's political independence.[160] He also began—although never finished—a novel partly based on his life experiences.[161] He continued to give lectures around the country, including to groups of East African soldiers stationed in Britain.[162] He became frustrated by the distance between him and Kenya, telling Edna that he felt "like a general separated by 5000 miles from his troops".[163] While he was absent, Kenya's authorities banned the KCA in 1940.[164]

Kenyatta and other senior IASB members began planning the fifth Pan-African Congress, held in Manchester in October 1945.[165] They were assisted by Kwame Nkrumah, a Gold Coast (Ghanaian) who arrived in Britain earlier that year.[166] Kenyatta spoke at the conference, although made no particular impact on the proceedings.[167] Much of the debate that took place centred on whether indigenous Africans should continue pursuing a gradual campaign for independence or whether they should seek the military overthrow of the European imperialists.[168] The conference ended with a statement declaring that while delegates desired a peaceful transition to African self-rule, Africans "as a last resort, may have to appeal to force in the effort to achieve Freedom".[167] Kenyatta supported this resolution, although was more cautious than other delegates and made no open commitment to violence.[169] He subsequently authored an IASB pamphlet, Kenya: The Land of Conflict, in which he blended political calls for independence with romanticised descriptions of an idealised pre-colonial African past.[170]

Return to Kenya

Presidency of the Kenya African Union: 1946–1952

After British victory in World War II, Kenyatta received a request to return to Kenya in September 1946, sailing back that month.[171] He decided not to bring Edna—who was pregnant with a second child[172]—with him, aware that if they joined him in Kenya their lives would be made very difficult by the colony's racial laws.[173] On his arrival in Mombasa, Kenyatta was greeted by his first wife, Grace Wahu and their children.[174] He built a bungalow at Gatundu, near to where he was born, and began farming his 32-acre estate.[175] Kenyatta met with the new Governor of Kenya, Philip Euen Mitchell, and in March 1947 accepted a post on an African Land Settlement Board, holding the post for two years.[176] He also met with Mbiyu Koinange to discuss the future of the Koinange Independent Teachers' College in Githungui, Koinange appointing Kenyatta as its Vice-Principal.[177] In May 1947, Koinange moved to England, leaving Kenyatta to take full control of the college.[178] Under Kenyatta's leadership, additional funds were raised for the construction of school buildings and the number of boys in attendance rose from 250 to 900.[179] It was also beset with problems, including a decline in standards and teachers' strikes over non-payment of wages. Gradually, the number of enrolled pupils fell.[180] Kenyatta built a friendship with Koinange's father, a Senior Chief, who gave Kenyatta one of his daughters to take as his third wife.[177] She bore him another child, but later died in childbirth.[181] In 1951, he married his fourth wife, Ngina, who was one of the few female students at his college; she then gave birth to a daughter.[182]

In August 1944, the Kenya African Union (KAU) had been founded; at that time it was the only active political outlet for indigenous Africans in the colony.[184] At its June 1947 annual general meeting, KAU's President James Gichuru stepped down and Kenyatta was elected as his replacement.[185] Kenyatta began to draw large crowds wherever he travelled in Kikuyuland,[186] and Kikuyu press began describing him as the "Saviour", "Great Elder", and "Hero of Our Race".[187] He was nevertheless aware that to achieve independence, KAU needed the support of other indigenous tribes and ethnic groups.[188] This was made difficult by the fact that many Maasai and Luo—tribes traditionally hostile to the Kikuyu—regarded him as an advocate of Kikuyu dominance.[189] He insisted on intertribal representation on the KAU executive and ensured that party business was conducted in Swahili, the lingua franca of indigenous Kenyans.[189]

To attract support from Kenya's Indian community, he made contact with Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of the new Indian republic. Nehru's response was supportive, sending a message to Kenya's Indian minority reminding them that they were the guests of the indigenous African population.[186] Relations with the white minority remained strained; for most white Kenyans, Kenyatta was their principal enemy, an agitator with links to the Soviet Union who had the impertinence to marry a white woman.[190] They too increasingly called for further Kenyan autonomy from the British government, but wanted continued white-minority rule and closer links to the white-minority governments of South Africa, Northern Rhodesia, and Southern Rhodesia; they viewed Britain's newly elected Labour government with great suspicion.[191] The white Electors' Union put forward a "Kenya Plan" which proposed greater white settlement in Kenya, bringing Tanganyika into the British Empire, and incorporating it within their new British East African Dominion.[192] In April 1950, Kenyatta was present at a joint meeting of KAU and the East African Indian National Congress in which they both expressed opposition to the Kenya Plan.[193]

By 1952, Kenyatta was widely recognized as a national leader, both by his supporters and by his opponents.[194] As KAU leader, he was at pains to oppose all illegal activity, including workers' strikes.[195] He called on his supporters to work hard, and to abandon laziness, theft, and crime.[196] He also insisted that in an independent Kenya, all racial groups would be safeguarded.[197] Kenyatta's gradualist and peaceful approach contrasted with the growth of the Mau Mau Uprising, as armed guerrilla groups began targeting the white minority and members of the Kikuyu community who did not support them. By 1959, the Mau Mau had killed around 1,880 people.[198] For many young Mau Mau militants, Kenyatta was regarded as a hero,[199] and they included his name in the oaths they gave to the organisation; such oathing was a Kikuyu custom by which individuals pledged allegiance to another.[200] Kenyatta publicly distanced himself from the Mau Mau.[201] In April 1952, he began a speaking tour in which he denounced the Mau Mau to assembled crowds, insisting that independence must be achieved through peaceful means.[202] In August he attended a much-publicised mass meeting in Kiambu where—in front of 30,000 people—he said that "Mau Mau has spoiled the country. Let Mau Mau perish forever. All people should search for Mau Mau and kill it."[203] Despite Kenyatta's vocal opposition to the Mau Mau, KAU had moved towards a position of greater militancy.[193] At its 1951 AGM, more militant African nationalists had taken senior positions and the party officially announced its call for Kenyan independence within three years.[183] In January 1952, KAU members formed a secret Central Committee devoted to direct action, formulated along a cell structure.[183] Whatever Kenyatta's views on these developments, he had little ability to control them.[181] He was increasingly frustrated, and—without the intellectual companionship he experienced in Britain—felt lonely.[204]

Trial: 1952–1953

"We Africans are in the majority [in Kenya], and we should have self-government. That does not mean we should not take account of whites, provided we have the key position. We want to be friendly with whites. We don't want to be dominated by them."

—Kenyatta, quoted by the Daily Express, September 1952[205]

In October 1952, Kenyatta was arrested and driven to Nairobi, where he was taken aboard a plane and flown to Lokitaung, northwest Kenya, one of the most remote locations in the country.[206] From there he wrote to his family to let them know of his situation.[207] Kenya's authorities believed that detaining Kenyatta would help quell civil unrest.[208] Many white settlers wanted him exiled, but the government feared this would turn him into a martyr for the anti-colonialist cause.[209] They thought it better that he be convicted and imprisoned, although at the time had nothing to charge him with, and so began searching his personal files for evidence of criminal activity.[208] Eventually, they charged him and five senior KAU members with masterminding the Mau Mau, a proscribed group.[210] The historian John M. Lonsdale stated that Kenyatta had been made a "scapegoat",[211] while the historian A. B. Assensoh later suggested that the authorities "knew very well" that Kenyatta was not involved in the Mau Mau, but that they were nevertheless committed to silencing his calls for independence.[212]

The trial took place in Kapenguria, a remote area near the Ugandan border that the authorities hoped would not attract crowds or attention.[213] Together, Kenyatta, Bildad Kaggia, Fred Kubai, Paul Ngei, Achieng Oneko and Kung'u Karumba—the "Kapenguria Six"—were put on trial.[208] The defendants assembled an international and multiracial team of defence lawyers, including Chaman Lall, H. O. Davies, F. R. S. De Souza, and Dudley Thompson, led by British barrister and Member of Parliament Denis Nowell Pritt.[210] Pritt's involvement brought much media attention;[210] during the trial he faced government harassment and was sent death threats.[214] The judge selected, Ransley Thacker, had recently retired from the Supreme Court of Kenya;[210] the government knew he would be sympathetic to their case and gave him £20,000 to oversee it.[215] The trial lasted five months: Rawson Macharia, the main prosecution witness, turned out to have perjured himself; the judge had only recently been awarded an unusually large pension and maintained secret contact with the then colonial Governor Evelyn Baring.[216] The prosecution failed to produce any strong evidence that Kenyatta or the other accused had any involvement in managing the Mau Mau.[217]

In April 1953, Judge Thacker found the defendants guilty.[218] He sentenced them to seven years' hard labour, to be followed by indefinite restriction preventing them from leaving a given area without permission.[219] In addressing the court, Kenyatta stated that he and the others did not recognise the judge's findings; they claimed that the government had used them as scapegoats as a pretext to shut down KAU.[220] The historian Wunyabari O. Maloba later characterised it as "a rigged political trial with a predetermined outcome".[215] The government followed the verdict with a wider crackdown, banning KAU in June 1953,[221] and closing down most of the independent schools in the country, including Kenyatta's.[221] It appropriated his land at Gatundu and demolished his house.[222]

Kenyatta and the others were returned to Lokitaung, where they resided on remand while awaiting the results of the appeal process.[223] Pritt pointed out that Thacker had been appointed magistrate for the wrong district, a technicality voiding the whole trial; the Supreme Court of Kenya concurred and Kenyatta and the others were freed in July 1953, only to be immediately re-arrested.[223] The government took the case to the East African Court of Appeal, which reversed the Supreme Court's decision in August.[223] The appeals process resumed in October 1953, and in January 1954 the Supreme Court upheld the convictions against all but Oneko.[224] Pritt finally took the case to the Privy Council in London, but they refused his petition without providing an explanation. He later noted that this was despite the fact his case was one of the strongest he had ever presented during his career.[225] According to Murray-Brown, it is likely that political, rather than legal considerations, informed their decision to reject the case.[224]

Imprisonment: 1954–1961

During the appeal process, a prison had been built at Lokitaung, where Kenyatta and the four others were then interned.[226] The others were made to break rocks in the hot sun but Kenyatta, because of his age, was instead appointed their cook, preparing a daily diet of beans and posho.[227] In 1955, P. de Robeck became the District Officer, after which Kenyatta and the other inmates were treated more leniently.[228] In April 1954, they had been joined by a captured Mau Mau commander, Waruhiu Itote; Kenyatta befriended him, and gave him English lessons.[229] By 1957, the inmates had formed into two rival cliques, with Kenyatta and Itote on one side and the other KAU members—now calling themselves the "National Democratic Party"—on the other.[230] In one incident, one of his rivals made an unsuccessful attempt to stab Kenyatta at breakfast.[231] Kenyatta's health had deteriorated in prison; manacles had caused problems for his feet and he had eczema across his body.[232]

Kenyatta's imprisonment transformed him into a political martyr for many Kenyans, further enhancing his status.[194] A Luo anti-colonial activist, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, was the first to publicly call for Kenyatta's release, an issue that gained growing support among Kenya's anti-colonialists.[233] In 1955, the British writer Montagu Slater—a socialist sympathetic to Kenyatta's plight—released The Trial of Jomo Kenyatta, a book which raised the profile of the case.[234] In 1958, Rawson Macharia, the key witness in the state's prosecution of Kenyatta, signed an affidavit swearing that his evidence against Kenyatta had been false; this was widely publicised.[235] By the late 1950s, the imprisoned Kenyatta had become a symbol of African nationalism across the continent.[236]

His sentence served, in April 1959 Kenyatta was released from Lokitaung.[237] The administration then placed a restricting order on Kenyatta, forcing him to reside in the remote area of Lodwar, where he had to report to the district commissioner twice a day.[238] There, he was joined by his wife Ngina.[239] In October 1961 she bore him another son, Uhuru, and later on another daughter, Nyokabi, and a further son, Muhoho.[240] Kenyatta spent two years in Lodwar.[241] The Governor of Kenya, Patrick Muir Renison, insisted that it was necessary; in a March 1961 speech, he described Kenyatta an "African leader to darkness and death" and stated that if he were released, violence would erupt.[242]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

This indefinite detention was widely interpreted internationally as a reflection of the cruelties of British imperialism.[243] Calls for his release came from the Chinese government,[244] India's Nehru,[245] and Tanganyika's Prime Minister Julius Nyerere.[246] Kwame Nkrumah—whom Kenyatta had known since the 1940s and who was now President of a newly independent Ghana—personally raised the issue with British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and other UK officials,[247] with the Ghanaian government offering Kenyatta asylum in the event of his release.[248] Resolutions calling for his release were produced at the All-African Peoples' Conferences held in Tunis in 1960 and Cairo in 1961.[236] Internal calls for his release came from Kenyan Asian activists in the Kenya Indian Congress,[249] while a colonial government commissioned poll revealed that most of Kenya's indigenous Africans wanted this outcome.[250]

By this point, it was widely accepted that Kenyan independence was inevitable, the British Empire having been dismantled throughout much of Asia and Macmillan having made his "Wind of Change" speech.[251] In January 1960, the British government made its intention to free Kenya apparent.[252] It invited representatives of Kenya's anti-colonial movement to discuss the transition at London's Lancaster House. An agreement was reached that an election would be called for a new 65-seat Legislative Council, with 33 seats reserved for black Africans, 20 for other ethnic groups, and 12 as 'national members' elected by a pan-racial electorate.[212] It was clear to all concerned that Kenyatta was going to be the key to the future of Kenyan politics.[253]

After the Lancaster House negotiations, the anti-colonial movement had split into two parties, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), which was dominated by Kikuyu and Luo, and the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU), which was led largely by members of smaller ethnic groups like the Kalenjin and Maasai.[254] In May 1960, KANU nominated Kenyatta as its president, although the government vetoed it, insisting that he had been an instigator of the Mau Mau.[255] KANU then declared that it would refuse to take part in any government unless Kenyatta was freed.[256] KANU campaigned on the issue of Kenyatta's detainment in the February 1961 election, where it gained a majority of votes.[257] KANU nevertheless refused to form a government, which was instead created through a KADU-led coalition of smaller parties.[258] Kenyatta had kept abreast of these developments, although he had refused to back either KANU or KADU,[259] instead insisting on unity between the two parties.[260]

Preparing for independence: 1961–1963

Renison decided to release Kenyatta before Kenya achieved independence. He thought public exposure to Kenyatta prior to elections would make the populace less likely to vote for a man Renison regarded as a violent extremist.[261] In April 1961, the government flew Kenyatta to Maralal, where he maintained his innocence of the charges but told reporters that he bore no grudges.[262] He reiterated that he had never supported violence or the illegal oathing system used by the Mau Mau,[263] and denied having ever been a Marxist, stating: "I shall always remain an African Nationalist to the end".[264] In August, he was moved to Gatundu in Kikuyuland, where he was greeted by a crowd of 10,000.[265] There, the colonial government had built him a new house to replace that they had demolished.[266] Now a free man, he travelled to cities like Nairobi and Mombasa to make public appearances.[267] After his release, Kenyatta set about trying to ensure that he was the only realistic option as Kenya's future leader.[268] In August he met with Renison at Kiambu,[269] and was interviewed by the BBC's Face to Face.[267] In October 1961, Kenyatta formally joined KANU and accepted its presidency.[270] In January 1962 he was elected unopposed as KANU's representative for the Fort Hall constituency in the legislative council after its sitting member, Kariuki Njiiri, resigned.[271]

Kenyatta traveled elsewhere in Africa, visiting Tanganyika in October 1961 and Ethiopia in November at the invitation of their governments.[272] A key issue facing Kenya was a border dispute in North East Province, alongside Somalia. Ethnic Somalis inhabited this region and claimed it should be part of Somalia, not Kenya.[273] Kenyatta disagreed, insisting the land remain Kenyan,[274] and stated that Somalis in Kenya should "pack up [their] camels and go to Somalia".[275] In June 1962, Kenyatta travelled to Mogadishu to discuss the issue with the Somalian authorities, but the two sides could not reach an agreement.[276]

Kenyatta sought to gain the confidence of the white settler community. In 1962, the white minority had produced 80% of the country's exports and were a vital part of its economy, yet between 1962 and 1963 they were emigrating at a rate of 700 a month; Kenyatta feared that this white exodus would cause a brain drain and skills shortage that would be detrimental to the economy.[277] He was also aware that the confidence of the white minority would be crucial to securing Western investment in Kenya's economy.[278] Kenyatta made it clear that when in power, he would not sack any white civil servants unless there were competent black individuals capable of replacing them.[279] He was sufficiently successful that several prominent white Kenyans backed KANU in the subsequent election.[280]

In 1962 he returned to London to attend one of the Lancaster House conferences.[281] There, KANU and KADU representatives met with British officials to formulate a new constitution.[282] KADU desired a federalist state organised on a system they called Majimbo with six largely autonomous regional authorities, a two-chamber legislature, and a central Federal Council of Ministers who would select a rotating chair to serve as head of government for a one-year term. Renison's administration and most white settlers favoured this system as it would prevent a strong central government implementing radical reform.[283] KANU opposed Majimbo, believing that it served entrenched interests and denied equal opportunities across Kenya; they also insisted on an elected head of government.[284] At Kenyatta's prompting, KANU conceded to some of KADU's demands; he was aware that he could amend the constitution when in office.[285] The new constitution divided Kenya into six regions, each with a regional assembly, but also featured a strong central government and both an upper and a lower house.[282] It was agreed that a temporary coalition government would be established until independence, several KANU politicians being given ministerial posts.[286] Kenyatta accepted a minor position, that of the Minister of State for Constitutional Affairs and Economic Planning.[287]

The British government considered Renison too ill at ease with indigenous Africans to oversee the transition to independence and thus replaced him with Malcolm MacDonald as Governor of Kenya in January 1963.[288] MacDonald and Kenyatta developed a strong friendship;[289] the Briton referred to the latter as "the wisest and perhaps strongest as well as most popular potential Prime Minister of the independent nation to be".[290] MacDonald sped up plans for Kenyan independence, believing that the longer the wait, the greater the opportunity for radicalisation among African nationalists.[291] An election was scheduled for May, with self-government in June, followed by full independence in December.[292]

Leadership

Premiership: 1963–1964

The May 1963 general election pitted Kenyatta's KANU against KADU, the Akamba People's Party, and various independent candidates.[293] KANU was victorious with 83 seats out of 124 in the House of Representatives;[280] a KANU majority government replaced the pre-existing coalition.[294] On 1 June 1963, Kenyatta was sworn in as prime minister of the autonomous Kenyan government.[295] Kenya remained a monarchy, with Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state.[296] In November 1963, Kenyatta's government introduced a law making it a criminal offence to disrespect the Prime Minister, exile being the punishment.[297] Kenyatta's personality became a central aspect of the creation of the new state.[297] In December, Nairobi's Delamere Avenue was renamed Kenyatta Avenue,[298] and a bronze statue of him was erected beside the country's National Assembly.[297] Photographs of Kenyatta were widely displayed in shop windows,[297] and his face was also printed on the new currency.[297] In 1964, Oxford University Press published a collection of Kenyatta's speeches under the title of Harambee!.[299]

_proposed_-_1963.png.webp)

Kenya's first cabinet included not only Kikuyu but also members of the Luo, Kamba, Kisii, and Maragoli tribal groups.[300] In June 1963, Kenyatta met with Julius Nyerere and Ugandan President Milton Obote in Nairobi. The trio discussed the possibility of merging their three nations (plus Zanzibar) into a single East African Federation, agreeing that this would be accomplished by the end of the year.[301] Privately, Kenyatta was more reluctant regarding the arrangement and as 1964 came around the federation had not come to pass.[302] Many radical voices in Kenya urged him to pursue the project;[303] in May 1964, Kenyatta rejected a back-benchers resolution calling for speedier federation.[302] He publicly stated that talk of a federation had always been a ruse to hasten the pace of Kenyan independence from Britain, but Nyerere denied that this was true.[302]

Continuing to emphasize good relations with the white settlers, in August 1963 Kenyatta met with 300 white farmers at Nakuru. He reassured them that they would be safe and welcome in an independent Kenya, and more broadly talked of forgiving and forgetting the conflicts of the past.[304] Despite his attempts at wooing white support, he did not do the same with the Indian minority.[305] Like many indigenous Africans in Kenya, Kenyatta bore a sense of resentment towards this community, despite the role that many Indians had played in securing the country's independence.[306] He also encouraged the remaining Mau Mau fighters to leave the forests and settle in society.[278] Throughout Kenyatta's rule, many of these individuals remained out of work, unemployment being one of the most persistent problems facing his government.[306]

A celebration to mark independence was held in a specially constructed stadium on 12 December 1963. During the ceremony, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh—representing the British monarchy—formally handed over control of the country to Kenyatta.[307] Also in attendance were leading figures from the Mau Mau.[308] In a speech, Kenyatta described it as "the greatest day in Kenya's history and the happiest day in my life."[309] He had flown Edna and Peter over for the ceremony, and in Kenya they were welcomed into Kenyatta's family by his other wives.[310]

Disputes with Somalia over the Northern Frontier District (NFD) continued; for much of Kenyatta's rule, Somalia remained the major threat to his government.[311] To deal with sporadic violence in the region by Somali shifta guerrillas, Kenyatta sent soldiers into the region in December 1963 and gave them broad powers of arrest and seizure in the NFD in September 1964.[312] British troops were assigned to assist the Kenyan Army in the region.[313] Kenyatta also faced domestic opposition: in January 1964, sections of the army launched a mutiny in Nairobi, and Kenyatta called on the British Army to put down the rebellion.[314] Similar armed uprisings had taken place that month in neighboring Uganda and Tanganyika.[314] Kenyatta was outraged and shaken by the mutiny.[315] He publicly rebuked the mutineers, emphasising the need for law and order in Kenya.[316] To prevent further military unrest, he brought in a review of the salaries of the army, police, and prison staff, leading to pay rises.[315] Kenyatta also wanted to contain parliamentary opposition and at Kenyatta's prompting, in November 1964 KADU officially dissolved and its representatives joined KANU.[317] Two of the senior members of KADU, Ronald Ngala and Daniel arap Moi, subsequently became some of Kenyatta's most loyal supporters.[318] Kenya therefore became a de facto one-party state.[319]

Presidency: 1964–1978

In December 1964, Kenya was officially proclaimed a republic.[320] Kenyatta became its executive president,[321] combining the roles of head of state and head of government.[322] Over the course of 1965 and 1966, several constitutional amendments enhanced the president's power.[323] For instance, a May 1966 amendment gave the president the ability to order the detention of individuals without trial if he thought the security of the state was threatened.[324] Seeking the support of Kenya's second largest ethnic group, the Luo, Kenyatta appointed the Luo Oginga Odinga as his vice president.[325] The Kikuyu—who made up around 20 percent of population—still held most of the country's important government and administrative positions.[326] This contributed to a perception among many Kenyans that independence had simply seen the dominance of a British elite replaced by the dominance of a Kikuyu elite.[306]

Kenyatta's calls to forgive and forget the past were a keystone of his government.[327] He preserved some elements of the old colonial order, particularly in relation to law and order.[328] The police and military structures were left largely intact.[328] White Kenyans were left in senior positions within the judiciary, civil service, and parliament,[329] with the white Kenyans Bruce Mackenzie and Humphrey Slade being among Kenyatta's top officials.[330] Kenyatta's government nevertheless rejected the idea that the European and Asian minorities could be permitted dual citizenship, expecting these communities to offer total loyalty to the independent Kenyan state.[331] His administration pressured whites-only social clubs to adopt multi-racial entry policies,[332] and in 1964 schools formerly reserved for European pupils were opened to Africans and Asians.[332]

Kenyatta's government believed it necessary to cultivate a united Kenyan national culture.[333] To this end, it made efforts to assert the dignity of indigenous African cultures which missionaries and colonial authorities had belittled as "primitive".[334] An East African Literature Bureau was created to publish the work of indigenous writers.[335] The Kenya Cultural Centre supported indigenous art and music, and hundreds of traditional music and dance groups were formed; Kenyatta personally insisted that such performances were held at all national celebrations.[336] Support was given to the preservation of historic and cultural monuments, while street names referencing colonial figures were renamed and symbols of colonialism—like the statue of British settler Hugh Cholmondeley, 3rd Baron Delamere in Nairobi city centre—were removed.[335] The government encouraged the use of Swahili as a national language, although English remained the main medium for parliamentary debates and the language of instruction in schools and universities.[334] The historian Robert M. Maxon nevertheless suggested that "no national culture emerged during the Kenyatta era", most artistic and cultural expressions reflecting particular ethnic groups rather than a broader sense of Kenyanness, while Western culture remained heavily influential over the country's elites.[337]

Economic policy

Independent Kenya had an economy heavily molded by colonial rule; agriculture dominated while industry was limited, and there was a heavy reliance on exporting primary goods while importing capital and manufactured goods.[338] Under Kenyatta, the structure of this economy did not fundamentally change, remaining externally oriented and dominated by multinational corporations and foreign capital.[339] Kenyatta's economic policy was capitalist and entrepreneurial,[340] with no serious socialist policies being pursued;[341] its focus was on achieving economic growth as opposed to equitable redistribution.[342] The government passed laws to encourage foreign investment, recognising that Kenya needed foreign-trained specialists in scientific and technical fields to aid its economic development.[343] Under Kenyatta, Western companies regarded Kenya as a safe and profitable place for investment;[344] between 1964 and 1970, large-scale foreign investment and industry in Kenya nearly doubled.[342]

In contrast to his economic policies, Kenyatta publicly claimed he would create a democratic socialist state with an equitable distribution of economic and social development.[345] In 1965, when Thomas Mboya was minister for economic planning and development, the government issued a session paper titled "African Socialism and its Application to Planning in Kenya", in which it officially declared its commitment to what it called an "African socialist" economic model.[346] The session proposed a mixed economy with an important role for private capital,[347] with Kenyatta's government specifying that it would consider only nationalisation in instances where national security was at risk.[348] Left-wing critics highlighted that the image of "African socialism" portrayed in the document provided for no major shift away from the colonial economy.[349]

Kenya's agricultural and industrial sectors were dominated by Europeans and its commerce and trade by Asians; one of Kenyatta's most pressing issues was to bring the economy under indigenous control.[342] There was growing black resentment towards the Asian domination of the small business sector,[350] with Kenyatta's government putting pressure on Asian-owned businesses, intending to replace them with African-owned counterparts.[351] The 1965 session paper promised an "Africanization" of the Kenyan economy,[352] with the government increasingly pushing for "black capitalism".[351] The government established the Industrial and Commercial Development Corporation to provide loans for black-owned businesses,[351] and secured a 51% share in the Kenya National Assurance Company.[353] In 1965, the government established the Kenya National Trading Corporation to ensure indigenous control over the trade in essential commodities,[354] while the Trade Licensing Act of 1967 prohibited non-citizens from involvement in the rice, sugar, and maize trade.[355] During the 1970s, this expanded to cover the trade in soap, cement, and textiles.[354] Many Asians who had retained British citizenship were affected by these measures.[356] Between late 1967 and early 1968, growing numbers of Kenyan Asians migrated to Britain;[357] in February 1968 large numbers migrated quickly before a legal change revoked their right to do so.[358] Kenyatta was not sympathetic to those leaving: "Kenya's identity as an African country is not going to be altered by the whims and malaises of groups of uncommitted individuals."[358]

Under Kenyatta, corruption became widespread throughout the government, civil service, and business community.[359] Kenyatta and his family were tied up with this corruption as they enriched themselves through the mass purchase of property after 1963.[360] Their acquisitions in the Central, Rift Valley, and Coast Provinces aroused great anger among landless Kenyans.[361] His family used his presidential position to circumvent legal or administrative obstacles to acquiring property.[362] The Kenyatta family also heavily invested in the coastal hotel business, Kenyatta personally owning the Leonard Beach Hotel.[363] Other businesses they were involved with included ruby mining in Tsavo National Park, the casino business, the charcoal trade—which was causing significant deforestation—and the ivory trade.[364] The Kenyan press, which was largely loyal to Kenyatta, did not delve into this issue;[365] it was only after his death that publications appeared revealing the scale of his personal enrichment.[366] Kenyan corruption and Kenyatta's role in it was better known in Britain, although many of his British friends—including McDonald and Brockway—chose to believe Kenyatta was not personally involved.[367]

Land, healthcare, and education reform

The question of land ownership had deep emotional resonance in Kenya, having been a major grievance against the British colonialists.[368] As part of the Lancaster House negotiations, Britain's government agreed to provide Kenya with £27 million with which to buy out white farmers and redistribute their land among the indigenous population.[369] To ease this transition, Kenyatta made Bruce McKenzie, a white farmer, the Minister of Agriculture and Land.[369] Kenyatta's government encouraged the establishment of private land-buying companies that were often headed by prominent politicians.[370] The government sold or leased lands in the former White Highlands to these companies, which in turn subdivided them among individual shareholders.[370] In this way, the land redistribution programs favoured the ruling party's chief constituency.[371] Kenyatta himself expanded the land that he owned around Gatundu.[306] Kenyans who made claims to land on the basis of ancestral ownership often found the land given to other people, including Kenyans from different parts of the country.[371] Voices began to condemn the redistribution; in 1969, the MP Jean-Marie Seroney censured the sale of historically Nandi lands in the Rift to non-Nandi, describing the settlement schemes as "Kenyatta's colonization of the rift".[372]

In part fuelled by high rural unemployment, Kenya witnessed growing rural-to-urban migration under Kenyatta's government.[373] This exacerbated urban unemployment and housing shortages, with squatter settlements and slums growing up and urban crime rates rising.[374] Kenyatta was concerned by this, and promoted the reversal of this rural-to-urban migration, but in this was unsuccessful.[375] Kenyatta's government was eager to control the country's trade unions, fearing their ability to disrupt the economy.[353] To this end it emphasised social welfare schemes over traditional industrial institutions,[353] and in 1965 transformed the Kenya Federation of Labour into the Central Organization of Trade (COT), a body which came under strong government influence.[376] No strikes could be legally carried out in Kenya without COT's permission.[377] There were also measures to Africanise the civil service, which by mid-1967 had become 91% African.[378] During the 1960s and 1970s the public sector grew faster than the private sector.[379] The growth in the public sector contributed to the significant expansion of the indigenous middle class in Kenyatta's Kenya.[380]

The government oversaw a massive expansion in education facilities.[381] In June 1963, Kenyatta ordered the Ominda Commission to determine a framework for meeting Kenya's educational needs.[382] Their report set out the long-term goal of universal free primary education in Kenya but argued that the government's emphasis should be on secondary and higher education to facilitate the training of indigenous African personnel to take over the civil service and other jobs requiring such an education.[383] Between 1964 and 1966, the number of primary schools grew by 11.6%, and the number of secondary schools by 80%.[383] By the time of Kenyatta's death, Kenya's first universities—the University of Nairobi and Kenyatta University—had been established.[384] Although Kenyatta died without having attained the goal of free, universal primary education in Kenya, the country had made significant advances in that direction, with 85% of Kenyan children in primary education, and within a decade of independence had trained sufficient numbers of indigenous Africans to take over the civil service.[385]

Another priority for Kenyatta's government was improving access to healthcare services.[386] It stated that its long-term goal was to establish a system of free, universal medical care.[387] In the short-term, its emphasis was on increasing the overall number of doctors and registered nurses while decreasing the number of expatriates in those positions.[386] In 1965, the government introduced free medical services for out-patients and children.[387] By Kenyatta's death, the majority of Kenyans had access to significantly better healthcare than they had had in the colonial period.[387] Before independence, the average life expectancy in Kenya was 45, but by the end of the 1970s it was 55, the second-highest in Sub-Saharan Africa.[388] This improved medical care had resulted in declining mortality rates while birth rates remained high, resulting in a rapidly growing population; from 1962 to 1979, Kenya's population grew by just under 4% a year, the highest rate in the world at the time.[389] This put a severe strain on social services; Kenyatta's government promoted family planning projects to stem the birth-rate, but these had little success.[390]

Foreign policy

In part due to his advanced years, Kenyatta rarely traveled outside of Eastern Africa.[391] Under Kenyatta, Kenya was largely uninvolved in the affairs of other states, including those in the East African Community.[240] Despite his reservations about any immediate East African Federation, in June 1967 Kenyatta signed the Treaty for East African Co-operation.[392] In December he attended a meeting with Tanzanian and Ugandan representatives to form the East African Economic Community, reflecting Kenyatta's cautious approach toward regional integration.[392] He also took on a mediating role during the Congo Crisis, heading the Organisation of African Unity's Conciliation Commission on the Congo.[393]

Facing the pressures of the Cold War,[394] Kenyatta officially pursued a policy of "positive non-alignment".[395] In reality, his foreign policy was pro-Western and in particular pro-British.[396] Kenya became a member of the British Commonwealth,[397] using this as a vehicle to put pressure on the white-minority apartheid regimes in South Africa and Rhodesia.[398] Britain remained one of Kenya's foremost sources of foreign trade; British aid to Kenya was among the highest in Africa.[395] In 1964, Kenya and the UK signed a Memorandum of Understanding, one of only two military alliances Kenyatta's government made;[395] the British Special Air Service trained Kenyatta's own bodyguards.[399] Commentators argued that Britain's relationship with Kenyatta's Kenya was a neo-colonial one, with the British having exchanged their position of political power for one of influence.[400] The historian Poppy Cullen nevertheless noted that there was no "dictatorial neo-colonial control" in Kenyatta's Kenya.[395]

Although many white Kenyans accepted Kenyatta's rule, he remained opposed by white far-right activists; while in London at the July 1964 Commonwealth Conference, he was assaulted by Martin Webster, a British neo-Nazi.[401] Kenyatta's relationship with the United States was also warm; the United States Agency for International Development played a key role in helping respond to a maize shortage in Kambaland in 1965.[402] Kenyatta also maintained a warm relationship with Israel, including when other East African nations endorsed Arab hostility to the state;[403] he for instance permitted Israeli jets to refuel in Kenya on their way back from the Entebbe raid.[404] In turn, in 1976 the Israelis warned of a plot by the Palestinian Liberation Army to assassinate him, a threat he took seriously.[405]

Kenyatta and his government were anti-communist,[406] and in June 1965 he warned that "it is naive to think that there is no danger of imperialism from the East. In world power politics the East has as much designs upon us as the West and would like to serve their own interests. That is why we reject Communism. "[407] His governance was often criticised by communists and other leftists, some of whom accused him of being a fascist.[344] When Chinese Communist official Zhou Enlai visited Dar es Salaam, his statement that "Africa is ripe for revolution" was clearly aimed largely at Kenya.[344] In 1964, Kenyatta impounded a secret shipment of Chinese armaments that passed through Kenyan territory on its way to Uganda. Obote personally visited Kenyatta to apologise.[408] In June 1967, Kenyatta declared the Chinese Chargé d'Affairs persona non grata in Kenya and recalled the Kenyan ambassador from Peking.[344] Relations with the Soviet Union were also strained; Kenyatta shut down the Lumumba Institute—an educational organisation named after the Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba—on the basis that it was a front for Soviet influence in Kenya.[409]

Dissent and the one-party state

Kenyatta made clear his desire for Kenya to become a one-party state, regarding this as a better expression of national unity than a multi-party system.[410] In the first five years of independence, he consolidated control of the central government,[411] removing the autonomy of Kenya's provinces to prevent the entrenchment of ethnic power bases.[412] He argued that centralised control of the government was needed to deal with the growth in demands for local services and to assist quicker economic development.[412] In 1966, it launched a commission to examine reforms to local government operations,[412] and in 1969 passed the Transfer of Functions Act, which terminated grants to local authorities and transferred major services from provincial to central control.[413]

A major focus for Kenyatta during the first three and a half years of Kenya's independence were the divisions within KANU itself.[414] Opposition to Kenyatta's government grew, particularly following the assassination of Pio Pinto in February 1965.[306] Kenyatta condemned the assassination of the prominent leftist politician, although UK intelligence agencies believed that his own bodyguard had orchestrated the murder.[415] Relations between Kenyatta and Odinga were strained, and at the March 1966 party conference, Odinga's post—that of party vice president—was divided among eight different politicians, greatly limiting his power and ending his position as Kenyatta's automatic successor.[416] Between 1964 and 1966, Kenyatta and other KANU conservatives had been deliberately trying to push Odinga to resign from the party.[417] Under growing pressure, in 1966 Odinga stepped down as state vice president, claiming that Kenya had failed to achieve economic independence and needed to adopt socialist policies. Backed by several other senior KANU figures and trade unionists, he became head of the new Kenya Peoples Union (KPU).[418] In its manifesto, the KPU stated that it would pursue "truly socialist policies" like the nationalisation of public utilities; it claimed Kenyatta's government "want[ed] to build a capitalist system in the image of Western capitalism but are too embarrassed or dishonest to call it that."[419] The KPU were legally recognised as the official opposition,[420] thus restoring the country's two party system.[421]

The new party was a direct challenge to Kenyatta's rule,[421] and he regarded it as a communist-inspired plot to oust him.[422] Soon after the KPU's creation, the Kenyan Parliament amended the constitution to ensure that the defectors—who had originally been elected on the KANU ticket—could not automatically retain their seats and would have to stand for re-election.[423] This resulted in the election of June 1966.[424] The Luo increasingly rallied around the KPU,[425] which experienced localized violence that hindered its ability to campaign, although Kenyatta's government officially disavowed this violence.[426] KANU retained the support of all national newspapers and the government-owned radio and television stations.[427] Of the 29 defectors, only nine were re-elected on the KPU ticket;[428] Odinga was among them, having retained his Central Nyanza seat with a high majority.[429] Odinga was replaced as vice president by Joseph Murumbi,[430] who in turn would be replaced by Moi.[431]

In July 1969, Mboya—a prominent and popular Luo KANU politician—was assassinated by a Kikuyu.[432] Kenyatta had reportedly been concerned that Mboya, with U.S. backing, could remove him from the presidency,[433] and across Kenya there were suspicions voiced that Kenyatta's government was responsible for Mboya's death.[430] The killing sparked tensions between the Kikuyu and other ethnic groups across the country,[434] with riots breaking out in Nairobi.[425] In October 1969, Kenyatta visited Kisumu, located in Luo territory, to open a hospital. On being greeted by a crowd shouting KPU slogans, he lost his temper. When members of the crowd started throwing stones, Kenyatta's bodyguards opened fire on them, killing and wounding several.[435] In response to the rise of KPU, Kenyatta had introduced oathing, a Kikuyu cultural tradition in which individuals came to Gatundu to swear their loyalty to him.[436] Journalists were discouraged from reporting on the oathing system, and several were deported when they tried to do so.[437] Many Kenyans were pressured or forced to swear oaths, something condemned by the country's Christian establishment.[438] In response to the growing condemnation, the oathing was terminated in September 1969,[439] and Kenyatta invited leaders from other ethnic groups to a meeting in Gatundu.[440]