Primidone

Primidone, sold under various brand names, is a barbiturate medication that is used to treat partial and generalized seizures,[6] as well as essential tremors.[7] It is taken by mouth.[6]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Lepsiral, Mysoline, Resimatil, others |

| Other names | desoxyphenobarbital, desoxyphenobarbitone |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682023 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Anticonvulsant, barbiturate |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100%[3] |

| Protein binding | 25%[3] |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | Primidone: 5-18 h, Phenobarbital: 75-120 h,[3] PEMA: 16 h[4] Time to reach steady state: Primidone: 2-3 days, Phenobarbital&PEMA 1-4weeks[5] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.307 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H14N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 218.256 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include sleepiness, poor coordination, nausea, and loss of appetite.[6] Severe side effects may include suicide, psychosis, a lack of blood cells.[7][6] Use during pregnancy may result in harm to the baby.[6] Primidone is an anticonvulsant of the barbiturate class.[6] How it works is not entirely clear.[6]

Primidone was approved for medical use in the United States in 1954.[6] It is available as a generic medication.[7] In 2017, it was the 238th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[8][9]

Medical uses

Epilepsy

Licensed for generalized tonic-clonic and complex partial seizures in the United Kingdom.[10] In the United States, primidone is approved for adjunctive (in combination with other drugs) and monotherapy (by itself) use in generalized tonic-clonic seizures, simple partial seizures, and complex partial seizures, and myoclonic seizures.[10] In juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), it is a second-line therapy, reserved for when the valproates or lamotrigine do not work and when other second-line therapies—acetazolamide work either.[11]

Open-label case series have suggested that primidone is effective in the treatment of epilepsy.[12][13][14][15][16] Primidone has been compared to phenytoin,[17] phenobarbital,[17] mephobarbital, ethotoin, metharbital, and mephenytoin.[17] In adult comparison trials, primidone has been found to be just as effective.[17]

Essential tremor

Primidone is considered to be a first-line therapy for essential tremor along with propranolol. In terms of tremor amplitude reduction, it is just as effective as propranolol, reducing it by 50%. Both drugs are well studied for this condition, unlike other therapies, and are recommended for initial treatment. 250 mg/day (low-dose therapy) is just as good as 750 mg/day (high-dose therapy).[18]

Primidone is not the only anticonvulsant used for essential tremor; the others include topiramate and gabapentin. Other pharmacological agents include alprazolam, clonazepam, atenolol, sotalol, nadolol, clozapine, nimodipine, and botulinum toxin A. Many of these drugs were less effective (according to Table 1), but a few were not. Only propranolol has been compared to primidone in a clinical trial.[18]

Psychiatric disorders

In 1965, Monroe and Wise reported using primidone along with a phenothiazine derivative antipsychotic and chlordiazepoxide in treatment-resistant psychosis.[19] What is known is that ten years later, Monroe went on to publish the results of a meta-analysis of two controlled clinical trials on people displaying out-of-character and situationally inappropriate aggression, who had abnormal EEG readings, and who responded poorly to antipsychotics; one of the studies was specifically mentioned as involving psychosis patients. When they were given various anticonvulsants not only did their EEGs improve, but so did the aggression.[20]

In March 1993, S.G. Hayes of the University of Southern California School of Medicine reported that nine out of twenty-seven people (33%) with either treatment-resistant depression or treatment-resistant bipolar disorder had a permanent positive response to primidone. A plurality of subjects were also given methylphenobarbital in addition to or instead of primidone.[21]

Adverse effects

Primidone can cause drowsiness, listlessness, ataxia, visual disturbances, nystagmus, headache, and dizziness. These side effects are the most common, occurring in more than 1% of users.[22] Transient nausea and vomiting are also common side effects.[23]

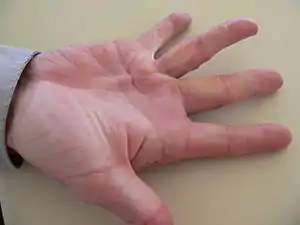

Dupuytren's contracture, a disease of the fasciae in the palm and fingers that permanently bends the fingers (usually the little and ring fingers) toward the palm, was first noted to be highly prevalent in epileptic people in 1941 by a Dr. Lund, fourteen years before primidone was on the market. Lund also noted that it was equally prevalent in individuals with idiopathic and symptomatic epilepsy and that the severity of the epilepsy did not matter. However, only one quarter of the women were affected vs. half of the men.[24] Thirty-five years later, Critcheley et al. reported a correlation between how long a patient had had epilepsy and his or her chance of getting Dupuytren's contracture. They suspected that this was due to phenobarbital therapy, and that the phenobarbital was stimulating peripheral tissue growth factors.[25] Dupuytren's contracture is almost exclusively found in Caucasians, especially those of Viking descent, and highest rates are reported in Northern Scotland, Norway, Iceland, and Australia. It has also been associated with alcoholism, heavy smoking, diabetes mellitus, physical trauma (either penetrating in nature or due to manual labor), tuberculosis, and HIV. People with rheumatoid arthritis are less likely to get this, and Drs. Hart and Hooper speculate that this is also true of gout due to the use of allopurinol. This is the only susceptibility factor that is generally agreed upon. Anticonvulsants do not seem to increase the incidence of Dupuytren's contracture in non-whites.[24]

Primidone has other cardiovascular effects in beyond shortening the QT interval. Both it and phenobarbital are associated with elevated serum levels (both fasting and six hours after methionine loading) of homocysteine, an amino acid derived from methionine. This is almost certainly related to the low folate levels reported in primidone users. Elevated levels of homocysteine have been linked to coronary heart disease. In 1985, both drugs were also reported to increase serum levels of high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, total cholesterol, and apolipoproteins A and B.[26]

It was first reported to exacerbate hepatic porphyria in 1975. In 1981, it was shown that phenobarbital, one of primidone's metabolites, only induced a significant porphyrin at high concentrations in vitro.[27] It can also cause elevations in hepatic enzymes such as gamma-glutamyl transferase and alkaline phosphatase.[22]

Less than 1% of primidone users will experience a rash. Compared to carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and phenytoin, this is very low. The rate is comparable to that of felbamate, vigabatrin, and topiramate.[28] Primidone also causes exfoliative dermatitis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.[22]

Primidone, along with phenytoin and phenobarbital, is one of the anticonvulsants most heavily associated with bone diseases such as osteoporosis, osteopenia (which can precede osteoporosis), osteomalacia and fractures.[29][30][31] The populations usually said to be most at risk are institutionalized people, postmenopausal women, older men, people taking more than one anticonvulsant, and children, who are also at risk of rickets.[29] However, it has been suggested that bone demineralization is most pronounced in young people (25–44 years of age)[30] and one 1987 study of institutionalized people found that the rate of osteomalacia in the ones taking anticonvulsants—one out of nineteen individuals taking an anticonvulsant (vs. none among the thirty-seven people taking none) —was similar to that expected in elderly people. The authors speculated that this was due to improvements in diet, sun exposure and exercise in response to earlier findings, and/or that this was because it was sunnier in London than in the Northern European countries which had earlier reported this effect.[31] In any case, the use of more than one anticonvulsant has been associated with an increased prevalence of bone disease in institutionalized epilepsy patients versus institutionalized people who did not have epilepsy. Likewise, postmenopausal women taking anticonvulsants have a greater risk of fracture than their drug-naive counterparts.[29]

Anticonvulsants affect the bones in many ways. They cause hypophosphatemia, hypocalcemia, low Vitamin D levels, and increased parathyroid hormone. Anticonvulsants also contribute to the increased rate of fractures by causing somnolence, ataxia, and tremor which would cause gait disturbance, further increasing the risk of fractures on top of the increase due to seizures and the restrictions on activity placed on epileptic people. Increased fracture rate has also been reported for carbamazepine, valproate and clonazepam. The risk of fractures is higher for people taking enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants than for people taking non-enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants.[30] In addition to all of the above, primidone can cause arthralgia.[22]

Granulocytopenia, agranulocytosis, and red-cell hypoplasia and aplasia, and megaloblastic anemia are rarely associated with the use of primidone.[32] Megaloblastic anemia is actually a group of related disorders with different causes that share morphological characteristics—enlarged red blood cells with abnormally high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratios resulting from delayed maturation of nuclei combined with normal maturation of cytoplasm, into abnormal megakaryocytes and sometimes hypersegmented neutrophils; regardless of etiology, all of the megaloblastic anemias involve impaired DNA replication.[33] The anticonvulsant users who get this also tend to eat monotonous diets devoid of fruits and vegetables.[34]

This antagonistic effect is not due to the inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase, the enzyme responsible for the reduction of dihydrofolic acid to tetrahydrofolic acid, but rather to defective folate metabolism.[35]

In addition to increasing the risk of megaloblastic anemia, primidone, like other older anticonvulsants also increases the risk of neural tube defects,[36] and like other enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants, it increases the likelihood of cardiovascular defects, and cleft lip without cleft palate.[37] Epileptic women are generally advised to take folic acid,[36] but there is conflicting evidence regarding the effectiveness of vitamin supplementation in the prevention of such defects.[37][38]

Additionally, a coagulation defect resembling Vitamin K deficiency has been observed in newborns of mothers taking primidone.[36] Because of this, primidone is a Category D medication.[39]

Primidone, like phenobarbital and the benzodiazepines, can also cause sedation in the newborn and also withdrawal within the first few days of life; phenobarbital is the most likely out of all of them to do that.[36]

In May 2005, Dr. M. Lopez-Gomez's team reported an association between the use of primidone and depression in epilepsy patients; this same study reported that inadequate seizure control, posttraumatic epilepsy, and polytherapy were also risk factors. Polytherapy was also associated with poor seizure control. Out of all of the risk factors, usage of primidone and inadequate seizure control were the greatest; with ORs of 4.089 and 3.084, respectively. They had been looking for factors associated with depression in epilepsy patients.[40] Schaffer et al. 1999 reported that one of their treatment failures, a 45-year-old woman taking 50 mg a day along with lithium 600 mg/day, clozapine 12.5 mg/day, trazodone 50 mg/day, and alprazolam 4 mg/day for three and a half months experienced auditory hallucinations that led to discontinuation of primidone.[41] It can also cause hyperactivity in children;[42] this most commonly occurs at low serum levels.[43] There is one case of an individual developing catatonic schizophrenia when her serum concentration of primidone went above normal.[44]

Primidone is one of the anticonvulsants associated with anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome, others being carbamazepine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital. This syndrome consists of fever, rash, peripheral leukocytosis, lymphadenopathy, and occasionally hepatic necrosis.[45]

Hyperammonemic encephalopathy was reported by Katano Hiroyuki of the Nagoya City Higashi General Hospital in early 2002 in a patient who had been stable on primidone monotherapy for five years before undergoing surgery for astrocytoma, a type of brain tumor. Additionally, her phenobarbital levels were inexplicably elevated post-surgery. This is much more common with the valproates than with any of the barbiturates.[46] A randomized controlled trial whose results were published in the July 1985 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine found that primidone was more likely to cause impotence than phenytoin, carbamazepine, or phenobarbital.[23] Like phenytoin, primidone is rarely associated with lymphadenopathy.[47] Primidone can also cause vomiting; this happens in 1.0–0.1% of users.[22]

Overdose

The most common symptoms of primidone overdose are coma with loss of deep tendon reflexes and, during the recovery period, if the patient survives, disorientation, dysarthria, nystagmus, and ataxia,[48] lethargy, somnolence, vomiting, nausea, and occasionally, focal neurological deficits which lessen over time.[49] Complete recovery comes within five to seven days of ingestion.[48] The symptoms of primidone poisoning have generally been attributed to its biotransformation to phenobarbital; however, primidone has toxic effects independent of its metabolites in humans.[49] The massive crystalluria that sometimes occurs sets its symptom profile apart from that of phenobarbital.[48][50][51][52] The crystals are white,[49][51] needle-like,[50] shimmering, hexagonal plates consisting mainly of primidone.[49][51]

In the Netherlands alone, there were thirty-four cases of suspected primidone poisoning between 1978 and 1982. Out of these, Primidone poisoning was much less common than phenobarbital poisoning. Twenty-seven of those adult cases were reported to the Dutch National Poison Control Center. Out of these, one person taking it with phenytoin and phenobarbital died, twelve became drowsy and four were comatose.[50]

Treatments for primidone overdose have included hemoperfusion with forced diuresis,[50] a combination of bemegride and amiphenazole;[53] and a combination of bemegride, spironolactone, caffeine, pentylenetetrazol, strophanthin, penicillin and streptomycin.[54]

In the three adults who are reported to have succumbed, the doses were 20–30 g.[48][53][54] However, two adult survivors ingested 30 g[48] 25 g,[53] and 22.5 g.[49] One woman experienced symptoms of primidone intoxication after ingesting 750 mg of her roommate's primidone.[55]

Interactions

Taking primidone with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) such as isocarboxazid (Marplan), phenelzine (Nardil), procarbazine (Matulane), selegiline (Eldepryl), tranylcypromine (Parnate) or within two weeks of stopping any one of them may potentiate the effects of primidone or change one's seizure patterns.[56] Isoniazid, an antitubercular agent with MAOI properties, has been known to strongly inhibit the metabolism of primidone.[57]

Like many anticonvulsants, primidone interacts with other anticonvulsants. Clobazam decreases clearance of primidone,[58] Mesuximide increases plasma levels of phenobarbital in primidone users,[59] both primidone and phenobarbital accelerate the metabolism of carbamazepine via CYP3A4,[60] and lamotrigine's apparent clearance is increased by primidone.[61] In addition to being an inducer of CYP3A4, it is also an inducer of CYP1A2, which causes it to interact with substrates such as fluvoxamine, clozapine, olanzapine, and tricyclic antidepressants.[62] It also interacts with CYP2B6 substrates such as bupropion, efavirenz, promethazine, selegiline, and sertraline; CYP2C8 substrates such as amiodarone, paclitaxel, pioglitazone, repaglinide, and rosiglitazone; and CYP2C9 substrates such as bosentan, celecoxib, dapsone, fluoxetine, glimepiride, glipizide, losartan, montelukast, nateglinide, paclitaxel, phenytoin, sulfonamides, trimethoprim, warfarin, and zafirlukast. It also interacts with estrogens.[56]

Primidone and the other enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants can cut the half-life of antipyrine roughly in half (6.2 ± 1.9 h vs. 11.2 ± 4.2 h), and increases the clearance rate by almost 70%. Phenobarbital reduces the half-life to 4.8 ± 1.3 and increases the clearance by almost 109%.[63] It also interferes with the metabolism of dexamethasone, a synthetic steroid hormone, to the point where its withdrawal from the regimen of a 14-year-old living in the United Kingdom made her hypercortisolemic.[64] Tempelhoff and colleagues at the Washington University School of Medicine's Department of Anesthesiology reported in 1990 that primidone and other anticonvulsant drugs increase the amount of fentanyl needed during craniotomy based on the patient's heart rate.[65]

Mechanism of action

The exact mechanism of primidone's anticonvulsant action is still unknown after over fifty years.[66] It is believed to work via interactions with voltage-gated sodium channels which inhibit high-frequency repetitive firing of action potentials.[67] The effect of primidone in essential tremor is not mediated by PEMA.[68] The major metabolite, phenobarbital, is also a potent anticonvulsant in its own right and likely contributes to primidone's effects in many forms of epilepsy. According to Brenner's Pharmacology textbook, Primidone also increases GABA-mediated chloride flux: thereby hyperpolarizing the membrane potential. Primidone was recently shown to directly inhibit the TRPM3 ion channel;[69] whether this effect contributes to its anticonvulsant effect is not known, but gain of function mutations in TRPM3 were recently shown to be associated with epilepsy and intellectual disability.[70]

Pharmacokinetics

Primidone converts to phenobarbital and PEMA;[71] it is still unknown which exact cytochrome P450 enzymes are responsible.[57] The phenobarbital, in turn, is metabolized to p-hydroxyphenobarbital.[72] The rate of primidone metabolism was greatly accelerated by phenobarbital pretreatment, moderately accelerated by primidone pretreatment, and reduced by PEMA pretreatment.[73] In 1983, a new minor metabolite, p-hydroxyprimidone, was discovered.[74]

Primidone, carbamazepine, phenobarbital and phenytoin are among the most potent hepatic enzyme inducing drugs in existence. This enzyme induction occurs at therapeutic doses. In fact, people taking these drugs have displayed the highest degree of hepatic enzyme induction on record.[63] In addition to being an inducer of CYP3A4, it is also an inducer of CYP1A2, which causes it to interact with substrates such as fluvoxamine, clozapine, olanzapine, and tricyclic antidepressants, as well as potentially increasing the toxicity of tobacco products. Its metabolite, phenobarbital, is a substrate of CYP2C9,[62] CYP2B6,[75] CYP2C8, CYP2C19, CYP2A6, CYP3A5,[76] CYP1E1, and the CYP2E subfamily.[77] The gene expression of these isoenzymes is regulated by human pregnane receptor X (PXR) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR). Phenobarbital induction of CYP2B6 is mediated by both.[76][78] Primidone does not activate PXR.[79]

The rate of metabolism of primidone into phenobarbital was inversely related to age; the highest rates were in the oldest patients (the maximum age being 55).[80] People aged 70–81, relative to people aged 18–26, have decreased renal clearance of primidone, phenobarbital, and PEMA, in ascending order of significance, and that there was a greater proportion of PEMA in the urine.[81] The clinical significance is unknown.

The percentage of primidone converted to phenobarbital has been estimated to be 5% in dogs and 15% in humans. Work done twelve years later found that the serum phenobarbital 0.111 mg/100 mL for every mg/kg of primidone ingested. Authors publishing a year earlier estimated that 24.5% of primidone was metabolized to phenobarbital. However, the patient reported by Kappy and Buckley would have had a serum level of 44.4 mg/100 mL instead of 8.5 mg/100 mL if this were true for individuals who have ingested large dose. The patient reported by Morley and Wynne would have had serum barbiturate levels of 50 mg/100 mL, which would have been fatal.[48]

History

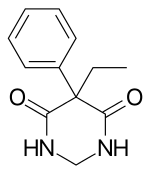

Primidone is a congener of phenobarbital where the carbonyl oxygen of the urea moiety is replaced by two hydrogen atoms.[82] The effectiveness of Primidone for epilepsy was first demonstrated in 1949 by Yule Bogue.[12] He found it to have a similar anticonvulsant effect to phenobarbitol, but more specific, i.e. with fewer associated sedative effects.[83]

It was brought to market a year later by the Imperial Chemical Industry (ICI), now known as AstraZeneca in the United Kingdom[53][84] and Germany.[54] In 1952, it was approved in the Netherlands.[50]

Also in 1952, Drs. Handley and Stewart demonstrated its effectiveness in the treatment of patients who failed to respond to other therapies; it was noted to be more effective in people with idiopathic generalized epilepsy than in people whose epilepsy had a known cause.[12] Dr. Whitty noted in 1953 that it benefitted patients with psychomotor epilepsy, who were often treatment-resistant. Toxic effects were reported to be mild.[13] That same year, it was approved in France.[85] Primidone was introduced in 1954 under the brandname Mysoline by Wyeth in the United States.[86]

Association with megaloblastic anemia

In 1954, Chalmers and Boheimer reported that the drug was associated with megaloblastic anemia.[87] Between 1954 and 1957, twenty-one cases of megaloblastic anemia associated with primidone and/or phenytoin were reported.[88] In most of these cases the anemia was due to vitamin deficiencies: usually folic acid deficiency; in one case Vitamin B12 deficiency[87] and in one case Vitamin C deficiency.[88] Some cases were associated with deficient diets: one patient ate mostly bread and butter,[87] another ate bread, buns, and hard candy, and another could rarely be persuaded to eat in the hospital.[88]

The idea that folic acid deficiency could cause megaloblastic anemia was not new. What was new was the idea that drugs could cause this in well-nourished people with no intestinal abnormalities.[87] In many cases, it was not clear which drug had caused it.[89] It was speculated that this might be related to the structural similarity between folic acid, phenytoin, phenobarbital, and primidone.[90] Folic acid had been found to alleviate the symptoms of megaloblastic anemia in the 1940s, not long after it was discovered, but the typical patient only made a full recovery—cessation of CNS and PNS symptoms as well as anemia—on B12 therapy.[91] Five years earlier, folic acid deficiency was linked to birth defects in rats.[92] Primidone was seen by some as too valuable to withhold based on the slight possibility of this rare side effect[87] and by others as dangerous enough to be withheld unless phenobarbital or some other barbiturate failed to work for this and other reasons (i.e., reports of permanent psychosis).[93]

Available forms

Primidone is available as a 250 mg/5mL suspension, and in the form of 50 mg, 125 mg, and 250 mg tablets. It is also available in a chewable tablet formulation in Canada.[94]

It is marketed as several different brands including Mysoline (Canada,[95] Ireland,[96] Japan,[97] the United Kingdom,[98] and the United States[95]), Prysoline (Israel, Rekah Pharmaceutical Products, Ltd.),[99] Apo-Primidone,[94][100] Liskantin (Germany, Desitin),[101] Resimatil (Germany, Sanofi-Synthélabo GmbH),[102] Mylepsinum (Germany, AWD.pharma GmbH & Co., KG).,[103] and Sertan (Hungary, 250 mg tablets, ICN Pharmaceuticals Inc.)

Other animals

Primidone has veterinary uses, including the prevention of aggressive behavior and cannibalism in gilt pigs, and treatment of nervous disorders in dogs and other animals.[104][105]

References

- "Primidone (Mysoline) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 18 February 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Primidone SERB 50mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 18 August 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Ochoa, Juan G; Riche, Willise. (2005). "Antiepileptic Drugs: An Overview". eMedicine. eMedicine, Inc. Retrieved 2005-07-02.

- CDER, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES (2003–2005). "Primidone (Mysoline)". Pharmacology Guide for Brain Injury Treatment. Brain Injury Resource Foundation. Retrieved 2005-07-02.

- Yale Medical School, Department of Laboratory Medicine (1998). "Therapeutic Drug Levels". YNHH Laboratory Manual - Reference Documents. Yale Medical School. Retrieved 2005-07-13.

- "Primidone Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 332. ISBN 9780857113382.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Primidone - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Acorus Therapeutics, Ltd. (2005). "Mysoline 250 mg Tablets". electronic Medicines Compendium. Datapharm Communications and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI). Archived from the original on 2008-03-16. Retrieved 2006-03-08.

- Broadley, Marissa A. (200). "Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy of Janz (JME)". The Childhood Seizure e-Book. Valhalla, New York. Archived from the original on 2005-06-07. Retrieved 2005-07-03.

- Williams, Denis (1 August 1956). "Treatment of Epilepsy with Mysoline". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 49 (8): 589–91. PMC 1889099. PMID 13359420.

- Whitty, C. W. (September 5, 1953). "Value of primidone in epilepsy". British Medical Journal. 2 (4835): 540–1. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4835.540. PMC 2029655. PMID 13082031.

- Livingston, Samuel; Don Petersen (February 16, 1956). "Primidone (mysoline) in the treatment of epilepsy; results of treatment of 486 patients and review of the literature". New England Journal of Medicine. 254 (7): 327–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM195602162540706. PMID 13288784.

- Smith, Bernard H.; Francis L. McNaughton (May 1953). "Mysoline, a new anticonvulsant drug; its value in refractory cases of epilepsy.|titlhoward stern babba booey e = Mysoline, A new Anticonvulsant: Its Value in Refractory Cases of Epilepsy". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 68 (5): 464–7. PMC 1822778. PMID 13042720.

- Powell, C.; Painter MJ; Pippenger CE (October 1984). "Primidone therapy in refractory neonatal seizures". Journal of Pediatrics. 105 (4): 651–4. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(84)80442-4. PMID 6481545.

- Gruber, C. M. Jr.; J. T. Brock; M. Dyken (January–February 1962). "Comparison of the effectiveness of phenobarital, mephobarbital, primidone, diphenylhydantoin, ethotoin, metharbital, and methylphenylethylhydantoin in motor seizures". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 3: 23–8. doi:10.1002/cpt19623123. PMID 13902356. S2CID 42871014.

- Zesiewicz TA, Elble R, Louis ED, Hauser RA, Sullivan KL, Dewey RB, Ondo WG, Gronseth GS, Weiner WJ (June 28, 2005). "Practice Parameter: Therapies for essential tremor: Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 64 (12): 2008–20. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000163769.28552.CD. PMID 15972843. Archived from the original on 2009-12-04. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- Monroe RR, Wise SP (1965). "Combined phenothiazine, chlordiazepoxide and primidone therapy for uncontrolled psychotic patients". American Journal of Psychiatry. 122 (6): 694–8. doi:10.1176/ajp.122.6.694. PMID 5320821.

- Monroe, R. R. (February 1975). "Anticonvulsants in the treatment of aggression". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 160 (2–1): 119–26. doi:10.1097/00005053-197502000-00006. PMID 1117287. S2CID 26067790.

- Hayes, S. G. (March 1993). "Barbiturate anticonvulsants in refractory affective disorders". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 5 (1): 35–44. doi:10.3109/10401239309148922. PMID 8348197.

- "Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). Official Acorus Therapeutics Site. Acorus Therapeutics. 2007-06-01. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

- Mattson RH; Cramer JA; Collins JF; Smith DB; Delgado-Escueta AV; Browne TR; Williamson PD; Treiman DM; et al. (July 8, 1985). "Comparison of carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and primidone in partial and secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures". New England Journal of Medicine. 313 (3): 145–51. doi:10.1056/NEJM198507183130303. PMID 3925335.

- Hart, M. G.; G. Hooper (July 2005). "Clinical associations of Dupuytren's disease". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 81 (957): 425–428. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.027425. PMC 1743313. PMID 15998816.

- Critchley EM, Vakil SD, Hayward HW, Owen VM (1976). "Dupuytren's disease in epilepsy: result of prolonged administration of anticonvulsants". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 39 (5): 498–503. doi:10.1136/jnnp.39.5.498. PMC 492313. PMID 932769.

- Schwaninger, Markus; Ringleb, P; Winter, R; Kohl, B; Fiehn, W; Rieser, PA; Walter-Sack, I (March 1999). "Elevated plasma concentrations of homocysteine in antiepileptic drug treatment". Epilepsia. 40 (3): 345–350. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00716.x. PMID 10080517. S2CID 42052760.

- Reynolds, N. C. Jr.; Miska, R. M. (April 1981). "Safety of anticonvulsants in hepatic porphyrias". Neurology. 31 (4): 480–4. doi:10.1212/wnl.31.4.480. PMID 7194443. S2CID 40044726.

- Arif H, Buchsbaum R, Weintraub D, Koyfman S, Salas-Humara C, Bazil CW, Resor SR, Hirsch LJ (May 15, 2007). "Comparison and predictors of rash associated with 15 antiepileptic drugs". Neurology. 68 (20): 1701–9. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000261917.83337.db. PMID 17502552. S2CID 32556955. Archived from the original on 2009-09-09. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- Pack, A. M.; M. J. Morrell (2001). "Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs on bone structure: epidemiology, mechanisms and therapeutic implications". CNS Drugs. 15 (8): 633–42. doi:10.2165/00023210-200115080-00006. PMID 11524035. S2CID 24519673.

- Valsamis, Helen A; Surender K Arora; Barbara Labban; Samy I McFarlane (September 6, 2006). "Antiepileptic drugs and bone metabolism". Nutrition & Metabolism. 3 (36): 36. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-3-36. PMC 1586194. PMID 16956398.

- Harrington, M. G.; H. M. Hodkinson (July 1987). "Anticonvulsant drugs and bone disease in the elderly". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 80 (7): 425–427. doi:10.1177/014107688708000710. PMC 1290903. PMID 3656313.

- "Mysoline". RxList. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2007-03-31. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

- Schick, Paul (2005). "Megaloblastic Anemia". eMedicine. Retrieved 2005-08-15.

- Reynolds, E. H.; J. F. Hallpike; B. M. Phillips; D. M. Matthews (September 1965). "Reversible absorptive defects in anticonvulsant megaloblastic anaemia". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 18 (5): 593–598. doi:10.1136/jcp.18.5.593. PMC 473011. PMID 5835440.

- Girdwood, R. H. (1976). "Drug-induced anaemias". Drugs. 11 (5): 394–404. doi:10.2165/00003495-197611050-00003. PMID 782836. S2CID 28324730.

- O'Brien, M. D.; S. K. Gilmour-White (2005). "Management of epilepsy in women". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 81 (955): 278–285. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.030221. PMC 1743264. PMID 15879038.

- Hernandez-Diaz S, S; Werler MM; Walker AM; Mitchell AA. (2000). "Folic acid antagonists during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects". New England Journal of Medicine. 343 (22): 1608–14. doi:10.1056/NEJM200011303432204. PMID 11096168.

- Biale, Y; H. Lewenthal (1984). "Effect of folic acid supplementation on congenital malformations due to anticonvulsive drugs". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 18 (4): 211–6. doi:10.1016/0028-2243(84)90119-9. PMID 6519344.

- Bruno, M. K.; C. L. Harden (January 2002). "Epilepsy in Pregnant Women". Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 4 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1007/s11940-002-0003-7. PMID 11734102. S2CID 22277001.

- Lopez-Gomez, M; J. Ramirez-Bermudez; C. Campillo; A. L. Sosa; M. Espinola; I. Ruiz (May 2005). "Primidone is associated with interictal depression in patients with epilepsy". Epilepsy & Behavior. 6 (3): 413–6. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.01.016. PMID 15820351. S2CID 23642891.

- Schaffer LC; Schaffer CB; Caretto J (June 1999). "The use of primidone in the treatment of refractory bipolar disorder". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 11 (2): 61–6. doi:10.3109/10401239909147050. PMID 10440522.

- Stores, G. (October 1975). "Behavioural effects of anti-epileptic drugs". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 17 (5): 647–58. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1975.tb03536.x. PMID 241674. S2CID 31753372.

- Herranz, J. L.; J. A. Armijo; R. Arteaga (November–December 1988). "Clinical side effects of phenobarbital, primidone, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproate during monotherapy in children". Epilepsia. 29 (6): 794–804. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb04237.x. PMID 3142761. S2CID 23611090.

- Sher, A.; J. M. Andersen; S. C. Bhatia (July–August 1983). "Primidone-induced catatonic schizophrenia". Drug Intelligence & Clinical Pharmacy. 17 (7–8): 551–2. doi:10.1177/106002808301700715. PMID 6872851. S2CID 35158990.

- Schlienger, Raymond G.; Shear, Neil H. (1998). "Antiepileptic drug hypersensitivity syndrome". Epilepsia. 39 (Suppl 7): S3–7. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01678.x. PMID 9798755. S2CID 38661360.

- Katano H, Fukushima T, Karasawa K, Sugiyama N, Ohkura A, Kamiya K (2002). "Primidone-induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy in a patient with cerebral astrocytoma". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 9 (1): 79–81. doi:10.1054/jocn.2001.1011. PMID 11749025. S2CID 13243424.

- Langlands, A. O.; N. Maclean; J. G. Pearson; E. R. Williamson (January 28, 1967). "Lymphadenopathy and megaloblastic anaemia in patient receiving primidone". British Medical Journal. 1 (5534): 215–217. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5534.215. PMC 1840532. PMID 4959849.

- Kappy, Michael S.; Jerome Buckley (April 1969). "Primidone intoxication in a child". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 44 (234): 282–4. doi:10.1136/adc.44.234.282. PMC 2020038. PMID 5779436.

- Brillman, J.; B. B. Gallagher; R. H. Mattson (March 1974). "Acute primidone intoxication". Archives of Neurology. 30 (3): 255–8. doi:10.1001/archneur.1974.00490330063011. PMID 4812959.

- van Heijst, A. N.; W. de Jong; R. Seldenrijk; A. van Dijk (June 1983). "Coma and crystalluria: a massive primidone intoxication treated with haemoperfusion". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 20 (4): 307–18. doi:10.3109/15563658308990598. PMID 6655772.

- Bailey, D. N.; P. I. Jatlow (November 1972). "Chemical analysis of massive crystalluria following primidone overdose". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 58 (5): 583–9. doi:10.1093/ajcp/58.5.583. PMID 4642162.

- Turner, C. R. (October 1980). "Primidone intoxication and massive crystalluria". Clinical Pediatrics. 19 (10): 706–7. doi:10.1177/000992288001901015. PMID 7408374. S2CID 30289848.

- Dotevall, Gerhard; Birger Herner (August 24, 1957). "Treatment of Acute Primidone Poisoning with Bemegride and Amiphenazole". British Medical Journal. 2 (5042): 451–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5042.451. PMC 1961943. PMID 13446511.

- Fazekas, I. Gy.; B. Rengei (January 1960). "Tödliche Vergiftung (Selbstmord) mit Mysoline und Phenobarbiturat". Archives of Toxicology (in German). 18 (4): 213–23. doi:10.1007/BF00577226. PMID 13698457. S2CID 35210736.

- Ajax, E. T. (October 1966). "An unusual case of primidone intoxication". Diseases of the Nervous System. 27 (10): 660–1. PMID 5919666.

- "Primidone". The Merck Manual's Online Medical Library. Lexi-Comp. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- Desta, Zeruesenay; Nadia V. Soukhova; David A. Flockhart (February 2001). "Inhibition of Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) Isoforms by Isoniazid: Potent Inhibition of CYP2C19 and CYP3A". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 45 (2): 382–92. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.2.382-392.2001. PMC 90302. PMID 11158730.

- Theis JG, Koren G, Daneman R, Sherwin AL, Menzano E, Cortez M, Hwang P (1997). "Interactions of clobazam with conventional antiepileptics in children". Journal of Child Neurology. 12 (3): 208–13. doi:10.1177/088307389701200311. PMID 9130097. S2CID 12698316.

- Browne, Thomas R.; Robert G. Feldman; Robert A. Buchanan RA; Nancy C. Allen; L. Fawcett-Vickers; GK Szabo; GF Mattson; SE Norman; DJ Greenblatt (April 1983). "Methsuximide for complex partial seizures: efficacy, toxicity, clinical pharmacology, and drug interactions". Neurology. 33 (4): 414–8. doi:10.1212/WNL.33.4.414. PMID 6403891. S2CID 73163592.

- Spina, Edoardo; Francesco Pisani; Emilio Perucca (September 1996). "Clinically significant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with carbamazepine. An update". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 31 (3): 198–214. doi:10.2165/00003088-199631030-00004. PMID 8877250. S2CID 22081046.

- GlaxoSmithKline (2005). "LAMICTAL Prescribing Information" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-13. Retrieved 2006-03-14.

- Spina, Edoardo; Emilio Perucca (February 2002). "Clinical Significance of Pharmacokinetic Interactions Between Antiepileptic and Psychotropic Drugs". Epilepsia. 43 (Suppl 2): 37–44. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.043s2037.x. PMID 11903482. S2CID 30800986.

- Perucca, E.; A. Hedges; K. A. Makki; M. Ruprah; J. F. Wilson; A. Richens (1984). "A comparative study of the relative enzyme inducing properties of anticonvulsant drugs in epileptic patients". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 18 (3): 401–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02311.x. PMC 1463658. PMID 6435654.

- Young MC, Hughes IA (1991). "Loss of therapeutic control in congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to interaction between dexamethasone and primidone". Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica. 80 (1): 120–4. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11744.x. PMID 2028784. S2CID 39118343.

- Tempelhoff R, Modica PA, Spitznagel EL (1990). "Anticonvulsant therapy increases fentanyl requirements during anaesthesia for craniotomy". Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 37 (3): 327–32. doi:10.1007/BF03005584. PMID 2108815.

- "Mysoline: Clinical Pharmacology". RxList. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- MacDonald, R. L.; K. M. Kelly (1995). "Antiepileptic drug mechanisms of action" (PDF). Epilepsia. 36 (Suppl 2): S2–12. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb05996.x. hdl:2027.42/65277. PMID 8784210. S2CID 22628709.

- Calzetti, S.; L. J. Findley; F. Pisani; A. Richens (October 1981). "Phenylethylmalonamide in essential tremor. A double-blind controlled study". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 44 (10): 932–934. doi:10.1136/jnnp.44.10.932. PMC 491180. PMID 7031184.

- Krügel, Ute; Straub, Isabelle; Beckmann, Holger; Schaefer, Michael (May 2017). "Primidone inhibits TRPM3 and attenuates thermal nociception in vivo". Pain. 158 (5): 856–867. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000846. ISSN 1872-6623. PMC 5402713. PMID 28106668.

- Zhao, Siyuan; Rohacs, Tibor (December 2021). "The newest TRP channelopathy: Gain of function TRPM3 mutations cause epilepsy and intellectual disability". Channels (Austin, Tex.). 15 (1): 386–397. doi:10.1080/19336950.2021.1908781. ISSN 1933-6969. PMC 8057083. PMID 33853504.

- Gatti, G.; M. Furlanut; E. Perrucca (2001-07-01). "Interindividual variability in the metabolism of anti-epileptic drugs and its clinical application". In Gian Maria Pacifici; Olavi Pelkonen (eds.). Interindividual Variability in Human Drug Metabolism. CRC Press. pp. 168. ISBN 978-0-7484-0864-1.

- Nau H; Jesdinsky D; Wittfoht W (1980). "Microassay for primidone and its metabolites phenylethylmalondiamide, phenobarbital and p-hydroxyphenobarbital in human serum, saliva, breast milk and tissues by gas chromatography—mass spectrometry using selected ion monitoring". Journal of Chromatography B. 182 (1): 71–9. doi:10.1016/S0378-4347(00)81652-7. PMID 7380904. Archived from the original on 2020-06-02. Retrieved 2005-10-16.

- Alvin J; Goh E; Bush MT (July 1975). "Study of the hepatic metabolism of primidone by improved methodology". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 194 (1): 117–25. PMID 1151744.

- Hooper WD; Treston AM; Jacobsen NW; Dickinson RG; Eadie MJ (November–December 1983). "Identification of p-hydroxyprimidone as a minor metabolite of primidone in rat and man". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 11 (6): 607–10. PMID 6140148.

- Lee, Anna M.; Sharon Miksys; Rachel F. Tyndale (July 2006). "Phenobarbital increases monkey in vivo nicotine disposition and induces liver and brain CYP2B6 protein". British Journal of Pharmacology. 148 (6): 786–4. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706787. PMC 1617079. PMID 16751792.

- Kojima, Koki; Kiyoshi Nagata; Tsutomu Matsubara; Yasushi Yamazoe (August 2007). "Broad but distinct role of pregnane x receptor on the expression of individual cytochrome p450s in human hepatocytes". Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 22 (4): 276–86. doi:10.2133/dmpk.22.276. PMID 17827782. Archived from the original on 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- Madan A, Graham RA, Carroll KM, Mudra DR, Burton LA, Krueger LA, Downey AD, Czerwinski M, Forster J, Ribadeneira MD, Gan LS, LeCluyse EL, Zech K, Robertson P, Koch P, Antonian L, Wagner G, Yu L, Parkinson A (April 2003). "Effects of Prototypical Microsomal Enzyme Inducers on Cytochrome P450 Expression in Cultured Human Hepatocytes". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 31 (4): 421–31. doi:10.1124/dmd.31.4.421. PMID 12642468. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- Li, Chien-Chun; Chong-Kuei Lii; Kai-Li Liu; Jaw-Ji Yang; Haw-Wen Chen (August 23, 2007). "DHA down-regulates phenobarbital-induced cytochrome P450 2B1 gene expression in rat primary hepatocytes by attenuating CAR translocation". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 225 (3): 329–36. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2007.08.009. PMID 17904175.

- Kobayashi, Kaoru; Saeko Yamagami; Tomoaki Higuchi; Masakiyo Hosokawa; Kan Chiba (April 2004). "Key structural features of ligands for activation of human pregnane X receptor". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 32 (4): 468–72. doi:10.1124/dmd.32.4.468. PMID 15039302. S2CID 35103040. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- Battino D, Avanzini G, Bossi L, Croci D, Cusi C, Gomeni C, Moise A (1983). "Plasma levels of primidone and its metabolite phenobarbital: effect of age and associated therapy". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 5 (1): 73–9. doi:10.1097/00007691-198303000-00006. PMID 6845402.

- Martines C, Gatti G, Sasso E, Calzetti S, Perucca E (1990). "The disposition of primidone in elderly patients". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 30 (4): 607–11. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03820.x. PMC 1368252. PMID 2291873.

- Goodman and Gilman, The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 1964 edition, p. 226.

- J.Y. Bogue and H.C. Carrington, "The evaluation of 'mysoline' -- a new anticonvulsant drug", British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy, 1953, 8, 230-236.

- Morley, D.; N. A. Wynne (January 12, 1957). "Acute Primidone Poisoning in a Child". British Medical Journal. 1 (5010): 90. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5010.90. PMC 1974075. PMID 13383203.

- Loiseau, Pierre Jean-Marie (June 1999). "Clinical Experience with New Antiepileptic Drugs: Antiepileptic Drugs in Europe". Epilepsia. 40 (Suppl 6): S3–8. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00925.x. PMID 10530675. S2CID 29638422.

- Wyeth. "Wyeth Timeline". About Wyeth. Archived from the original on 2009-01-07. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- Newman, M. J. D.; D. W. Sumner (February 1957). "Megaloblastic anemia following the use of primidone". Blood. 12 (2): 183–8. doi:10.1182/blood.V12.2.183.183. PMID 13403983.

- Kidd, Patrick; David L. Mollin (October 26, 1957). "Megaloblastic Anaemia and Vitamin-B12 Deficiency After Anticonvulsant Therapy". British Medical Journal. 2 (5051): 97–976. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2689.97. PMC 1962638. PMID 13472024.

- Fuld, H.; E. H. Moorhouse (May 5, 1956). "Observations on Megaloblastic Anaemias After Primidone". British Medical Journal. 1 (4974): 1021–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4974.1021. PMC 1979778. PMID 13304415.

- Girdwood, R. H.; J. A. R. Lenman (January 21, 1956). "Megaloblastic Anaemia Occurring During Primidone Therapy". British Medical Journal. 1 (4959): 146–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4959.146. PMC 1978898. PMID 13276653.

- Meyer, Leo M. (1 January 1947). "Folic Acid In The Treatment Of Pernicious Anemia". Blood. 2 (1): 50–62. doi:10.1182/blood.V2.1.50.50. PMID 20278334.

- Nelson, Marjorie M.; C. Willet Asling; Herbert M. Evans (1 September 1952). "Production of multiple congenital abnormalities in young by maternal pteroylglutamic acid deficiency during gestation". Journal of Nutrition. 48 (1): 61–79. doi:10.1093/jn/48.1.61. PMID 13000492.

- Garland, Hugh (August 1957). "Drugs used in the management of epilepsy". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 50 (8): 611–5. PMC 1889058. PMID 13465742.

- Schachter, Steven C. (February 2004). "Mysoline". Epilepsy.com. Epilepsy Therapy Development Project. Archived from the original on 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- "Valeant Pharmaceuticals International: Products". Archived from the original on 2005-06-01. Retrieved 2005-07-03.

- "Service List". Archived from the original on 15 May 2006. Retrieved 13 March 2006.

- Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma (2005). "Primidone 250 mg Tablets & Primidone 99.5% Powder" (PDF). Retrieved 13 March 2006.

- "Acorus Therapeutics Ltd. - Ordering - UK". acorus-therapeutics.com. Acorus Therapeutics. Archived from the original on 2005-04-07. Retrieved 2005-07-04.

- "Prysoline Tablets". The Israel Drug Registry. The State of Israel. 2005. Retrieved 2006-02-17.

- "APO-PRIMIDONE". Apotex. 2007-01-10. Archived from the original on 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- "Liskantin". Desitin. Archived from the original on 2005-08-22. Retrieved 2005-07-03.

- "Resimatil Tabletten". Deutsche Krankenversicherung AG. Retrieved 2005-07-03.

- "Mylepsinum Tabletten". Deutsche Krankenversicherung AG. Retrieved 2005-07-03.

- National Office of Animal Health. "Compendium of Veterinary Medicine". Archived from the original on 2007-10-06. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- The Pig Site. "Savaging of Piglets". Archived from the original on 2006-11-24. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

Further reading

- "Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Primidone in F344/N Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Feed Studies)" (PDF). Department of Health and Human Services National Toxicology Program. September 2000. Lay summary.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-url=(help)

External links

- "Primidone". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Testing Status of Primidone (primaclone) 10270-A". National Toxicology Program.