Londinium

Londinium, also known as Roman London, was the capital of Roman Britain during most of the period of Roman rule. It was originally a settlement established on the current site of the City of London around AD 47–50.[2][3] It sat at a key crossing point over the River Thames which turned the city into a road nexus and major port, serving as a major commercial centre in Roman Britain until its abandonment during the 5th century.

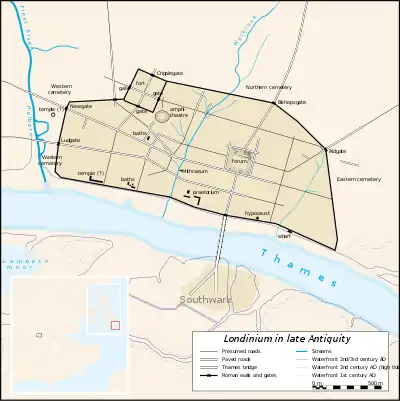

A general outline of Roman London in late antiquity, with the modern banks of the Thames.[1] Discovered roads drawn as double lines; conjectural roads, single lines. | |

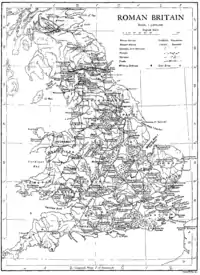

Location within Britain | |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°30′45″N 0°05′26″W |

| Type | Roman city |

| History | |

| Periods | Roman Empire |

Following the foundation of the town in the mid-1st century, early Londinium occupied the relatively small area of 1.4 km2 (0.5 sq mi), roughly half the area of the modern City of London and equivalent to the size of present-day Hyde Park. In the year 60 or 61, the rebellion of the Iceni under Boudica compelled the Roman forces to abandon the settlement, which was then razed. Following the defeat of Boudica by the Roman governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus a military installation was established[4] and the city was rebuilt. It had probably largely recovered within about a decade. During the later decades of the 1st century, Londinium expanded rapidly, becoming Britannia's largest city, and it was provided with large public buildings such as a forum[5] and amphitheatre.[6] By the turn of the century, Londinium had grown to perhaps 30,000 or 60,000 people, almost certainly replacing Camulodunum (Colchester) as the provincial capital, and by the mid-2nd century Londinium was at its height. Its forum-basilica was one of the largest structures north of the Alps when the Emperor Hadrian visited Londinium in 122. Excavations have discovered evidence of a major fire that destroyed much of the city shortly thereafter, but the city was again rebuilt. By the second half of the 2nd century, Londinium appears to have shrunk in both size and population.

Although Londinium remained important for the rest of the Roman period, no further expansion resulted. Londinium supported a smaller but stable settlement population as archaeologists have found that much of the city after this date was covered in dark earth—the by-product of urban household waste, manure, ceramic tile, and non-farm debris of settlement occupation, which accumulated relatively undisturbed for centuries. Some time between 190 and 225, the Romans built a defensive wall around the landward side of the city. The London Wall survived for another 1,600 years and broadly defined the perimeter of the old City of London.

| History of London |

|---|

|

| See also |

|

|

|

Name

The etymology of the name Londinium is unknown. Following Geoffrey of Monmouth's pseudohistorical History of the Kings of Britain,[7][8] it was long published as derived from an eponymous founder named Lud, son of Heli. There is no evidence such a figure ever existed. Instead, the Latin name was probably based on a native Brittonic place name reconstructed as *Londinion.[10] Morphologically, this points to a structure of two suffixes: -in-jo-. However, the Roman Londinium was not the immediate source of English "London" (Old English: Lunden), as i-mutation would have caused the name to have been Lyndon. This suggests an alternative Brittonic form Londonion;[13] alternatively, the local pronunciation in British Latin may have changed the pronunciation of Londinium to Lundeiniu or Lundein, which would also have avoided i-mutation in Old English.[14] The list of the 28 cities of Britain included in the 9th-century History of the Britons precisely notes London[15] in Old Welsh as Cair Lundem[16] or Lundein.[15][18]

Location

The site guarded the Romans' bridgehead on the north bank of the Thames and a major road nexus shortly after the invasion. It was centred on Cornhill and the River Walbrook, but extended west to Ludgate Hill and east to Tower Hill. Just prior to the Roman conquest, the area had been contested by the Catuvellauni based to the west and the Trinovantes based to the east; it bordered the realm of the Cantiaci on the south bank of the Thames.

The Roman city ultimately covered at least the area of the City of London, whose boundaries are largely defined by its former wall. Londinium's waterfront on the Thames ran from around Ludgate Hill in the west to the present site of the Tower in the east, around 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi). The northern wall reached Bishopsgate and Cripplegate near the Museum of London, a course now marked by the street "London Wall". Cemeteries and suburbs existed outside the city proper. A round temple has been located west of the city, although its dedication remains unclear.

Substantial suburbs existed at St Martin-in-the-Fields in Westminster and around the southern end of the Thames bridge in Southwark, where excavations in 1988[20] and 2021 have revealed an elaborate building with fine mosaics and frescoed walls dating from 72 AD.[21][22] Inscriptions suggest a temple of Isis was located there.[23]

Status

Londinium grew up as a vicus, and soon became an important port for trade between Britain and the Roman provinces on the continent. Tacitus wrote that, at the time of the uprising of Boudica, "Londinium... though undistinguished by the name of 'colony', was much frequented by a number of merchants and trading vessels."[25][26]

Depending on the time of its creation, the modesty of Londonium's first forum may have reflected its early elevation to city (municipium) status or may have reflected an administrative concession to a low-ranking but major Romano-British settlement.[27] It had almost certainly been granted colony (colonia) status prior to the complete replanning of the city's street plan attending the erection of the great second forum around the year 120.[28]

By this time, Britain's provincial administration had also almost certainly been moved to Londinium from Camulodunum (now Colchester in Essex). The precise date of this change is unknown, and no surviving source explicitly states that Londinium was "the capital of Britain" but there are several strong indications of this status: 2nd-century roofing tiles have been found marked by the "Procurator" or "Publican of the Province of Britain at Londinium",[30] the remains of a governor's palace and tombstones belonging to the governor's staff have been discovered, and the city was well defended and armed, with a new military camp erected at the beginning of the 2nd century in a fort on the north-western edge of the city, despite being far from any frontier.[31] Despite some corruption to the text, the list of bishops for the 314 Council of Arles indicates that either Restitutus or Adelphius came from Londinium.[34] The city seems to have been the seat of the diocesan vicar and one of the provincial governors following the Diocletian Reforms around the year 300; it had been renamed Augusta – a common epithet of provincial capitals – by 368.[35]

History

Founding

Unlike many cities of Roman Britain, Londinium was not placed on the site of a native settlement or oppidum.[36] Prior to the arrival of the Roman legions, the area was almost certainly lightly rolling open countryside traversed by numerous streams now underground. Ptolemy lists it as one of the cities of the Cantiaci,[37] but Durovernum (Roman Canterbury) was their tribal capital (civitas). It is possible that the town was preceded by a short-lived Roman military camp but the evidence is limited and this topic remains a matter of debate.[38][39]

Archaeologist Lacey Wallace notes that "Because no LPRIA settlements or significant domestic refuse have been found in London, despite extensive archaeological excavation, arguments for a purely Roman foundation of London are now common and uncontroversial."[40] The city's Latin name seems to have derived from an originally Brittonic one and significant pre-Roman finds in the Thames, especially the Battersea Shield (Chelsea Bridge, perhaps 4th-century BC) and the Wandsworth Shield (perhaps 1st-century BC), both assumed to be votive offerings deposited a couple of miles upstream of Londinium, suggest the general area was busy and significant. It has been suggested that the area was where a number of territories met.[41] There was probably a ford in that part of the river; other Roman and Celtic finds suggest this was perhaps where the opposed crossing Julius Caesar describes in 54 BC took place.

Londinium grew up around the point on the River Thames narrow enough for the construction of a Roman bridge but still deep enough to handle the era's seagoing ships.[42] Its placement on the Tideway permitted easier access for ships sailing upstream.[42][43] The remains of a massive pier base for such a bridge were found in 1981 close by the modern London Bridge.

Some Claudian-era camp ditches have been discovered,[44] but archaeological excavations undertaken since the 1970s by the Department of Urban Archaeology at the Museum of London (now MOLAS) have suggested the early settlement was largely the product of private enterprise.[45] A timber drain by the side of the main Roman road excavated at No 1 Poultry has been dated by dendrochronology to AD 47.[46]

Following its foundation in the mid-1st century, early Roman London occupied a relatively small area, about 350 acres (1.4 km2) or roughly the area of present-day Hyde Park. Archaeologists have uncovered numerous goods imported from across the Roman Empire in this period, suggesting that early Roman London was a highly cosmopolitan community of merchants from across the Empire and that local markets existed for such objects.

Roads

Of the fifteen British routes recorded in the 2nd- or 3rd-century Antonine Itinerary, seven ran to or from Londinium.[35][48] Most of these have been shown to have been initially constructed near the time of the city's foundation around AD 47.[49] The roads are now known by Welsh or Old English names, as their original Roman names have been entirely lost due to the lack of written and inscribed sources. (It was customary elsewhere to name roads after the emperor during whose principate they were completed, but the number and vicinity of routes completed during the time of Claudius would seem to have made this impractical in Britain's case.)

The road from the Kentish ports of Rutupiae (Richborough), Dubris (Dover), and Lemanis (Lympne) via Durovernum (Canterbury) seems to have first crossed the Thames at a natural ford near Westminster before being diverted north to the new bridge at London.[56] The Romans enabled the road to cross the marshy terrain without subsidence by laying down substrates of one to three layers of oak logs.[49][55] This route, now known as Watling Street, then passed through the town from the bridgehead in a straight line to reconnect with its northern extension towards Viroconium (Wroxeter) and the legionary base at Deva Victrix (Chester). The Great Road ran northeast across Old Ford to Camulodunum (Colchester) and thence northeast along Pye Road to Venta Icenorum (Caistor St Edmund). Ermine Street ran north from the city to Lindum (Lincoln) and Eboracum (York). The Devil's Highway connected Londinium to Calleva (Silchester) and its roads to points west over the bridges near modern Staines. A minor road led southwest to the city's main cemetery and the old routes to the ford at Westminster. Stane Street to Noviomagus (Chichester) did not reach Londinium proper but ran from the bridgehead in the southern suburb at Southwark. These roads varied from 12–20 m (39–66 ft) wide.[49]

After its reconstruction in the AD 60s, the streets largely adhered to a grid. The main streets were 9–10 m (30–33 ft) wide, while side streets were usually about 5 m (16 ft) wide.[49]

Boudica

In the year 60 or 61, a little more than ten years after Londinium was founded, the king of the Iceni died. He had possibly been installed by the Romans after the Iceni's failed revolt against P. Ostorius Scapula's disarmament of the allied tribes in AD 47[57] or may have assisted the Romans against his tribesmen during that revolt. His will had divided his wealth and lands between Rome and his two daughters, but Roman law forbade female inheritance and it had become common practice to treat allied kingdoms as life estates that were annexed upon the ruler's death, as had occurred in Bithynia[58] and Galatia.[59] Roman financiers including Seneca called in all the king's outstanding loans at once[60] and the provincial procurator confiscated the property of both the king and his nobles. Tacitus records that, when the king's wife Boudica objected, the Romans flogged her, raped her two daughters, and enslaved their nobles and kinsmen.[61] Boudica then led a failed revolt against Roman rule.

Two hundred ill-equipped men were sent to defend the provincial capital and Roman colony at Camulodunum, probably from the garrison at Londinium.[62] The Iceni and their allies overwhelmed them and razed the city. The 9th Legion under Q. Petillius Cerialis, coming south from the Fosse Way, was ambushed and annihilated. The procurator, meanwhile, escaped with his treasure to Gaul, probably via Londinium.[62] G. Suetonius Paulinus had been leading the 14th and 20th Legions in the Roman conquest of Anglesey; hearing of the rising, he immediately returned along Watling Street with the legions' cavalry.[62] An early historical record of London appears in Tacitus's account of his actions upon arriving and finding the state of the 9th Legion:[24][26]

At first, [Paulinus] hesitated as to whether to stand and fight there. Eventually, his numerical inferiority—and the price only too clearly paid by the divisional commander's rashness—decided him to sacrifice the single city of Londinium to save the province as a whole. Unmoved by lamentations and appeals, Suetonius gave the signal for departure. The inhabitants were allowed to accompany him. But those who stayed because they were women, or old, or attached to the place, were slaughtered by the enemy.

Excavation has revealed extensive evidence of destruction by fire in the form of a layer of red ash beneath the city at this date. Suetonius then returned to the legions' slower infantry, who met and defeated the British army, slaughtering as many as 70,000 men and camp followers. There is a long-standing folklore belief that this battle took place at King's Cross, simply because as a mediaeval village it was known as Battle Bridge. Suetonius's flight back to his men, the razing of Verulamium (St Albans), and the battle shortly thereafter at "a place with narrow jaws, backed by a forest",[24][26] speaks against the tradition and no supporting archaeological evidence has been yet discovered.[63]

1st century

After the sack of the city by Boudica and her defeat, a large military fort covering 15,000 m2 was built at Plantation Place on Cornhill, with 3m-high banks and enclosed by 3m deep double ditches.[64] It was built as an emergency solution to protect London's important trade and to help reconstruct the city. It dominated the town and lay over the main road into London controlling traffic from London Bridge and on the river. Several major building projects at this time such as roads, a new quay and a water lifting machine indicate the army had a key role in reconstruction. The fort was in use for less than 10 years.

The city was eventually rebuilt as a planned Roman town, its streets generally adhering to a grid skewed by major roads passing from the bridgehead and by changes in alignment produced by crossings over the local streams.[65] It recovered after about a decade.

The first forum was constructed in the 70s or 80s[27] and has been excavated, showing it had an open courtyard with a basilica and several shops around it, altogether measuring about 100 m × 50 m (330 ft × 160 ft).[66] The basilica would have functioned as the city's administrative heart, hearing law cases and seating the town's local senate. It formed the north side of the forum, whose south entrance was located along the north side of the intersection of the present Gracechurch, Lombard, and Fenchurch Streets.[67] Forums elsewhere typically had a civic temple constructed within the enclosed market area; British sites usually did not, instead placing a smaller shrine for Roman services somewhere within the basilica. The first forum in Londinium seems to have had a full temple, but placed outside just west of the forum.[68]

During the later decades of the 1st century, Londinium expanded rapidly and quickly became Roman Britain's largest city, although most of its houses continued to be made of wood. By the turn of the century, Londinium was perhaps as large as 60,000 people,[69][70] and had replaced Camulodunum (Colchester) as the provincial capital. A large building discovered near Cannon Street Station has had its foundation dated to this era and is assumed to have been the governor's palace. It boasted a garden, pools, and several large halls, some of which were decorated with mosaic floors.[71] It stood on the east bank of the now-covered Walbrook, near where it joins the Thames. The London Stone may originally have been part of the palace's main entrance. Another site dating to this era is the bathhouse (thermae) at Huggin Hill, which remained in use prior to its demolition around the year 200. Brothels were legal but taxed.[72]

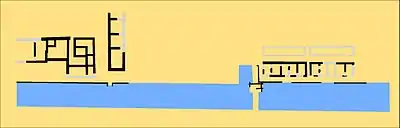

Port

The bulk of the Roman port was quickly rebuilt after Boudicca's rebellion[73] when the waterfront was extended with gravel to permit a sturdy wharf to be built perpendicular to the shore. The port was built in four sections, starting upstream of the London Bridge and working down towards the Walbrook at the centre of Londinium. Expansion of the flourishing port continued into the 3rd century. Scraps of armour, leather straps, and military stamps on building timbers suggest that the site was constructed by the city's legionaries.[74] Major imports included fine pottery, jewellery and wine.[75] Only two large warehouses are known, implying that Londinium functioned as a bustling trade centre rather than a supply depot and distribution centre like Ostia near Rome.[74]

2nd century

Emperor Hadrian visited Londinium in 122. The impressive public buildings from around this period may have been initially constructed in preparation for his visit or during the rebuilding that followed the "Hadrianic Fire". The so-called 'Hadrianic Fire' is not mentioned in any historical sources but has been inferred by evidence of large-scale burning identified by archaeologists on a number of excavation sites around the City of London.[76] The best dating evidence for this event(s) comes from burnt stocks of unsold Terra Sigilatta pottery, which can be dated to circa AD 120–125. These were found in destroyed warehouse or shop buildings at Regis House and Bucklersbury.[77] Hadrianic fire horizons tend to be dated to around the AD 120-130s but it is difficult to prove that they are precisely contemporary and there remains some uncertainty as to whether they indicate a single large fire or a series of smaller conflagrations.[76] Fire destroyed substantial areas of the city in the area north of the Thames but does not seem to have damaged many major public buildings. There is very little evidence to suggest similar burning in the adjacent Southwark settlement. The Hadrianic fire (or fires) has normally been assumed to be accidental[76] but it has also been suggested that it could relate to an episode of political turbulence.[78]

.jpg.webp)

During the early 2nd century, Londinium was at its height, having recovered from the fire and again had between 45,000 and 60,000 inhabitants around the year 140, with many more stone houses and public buildings erected. Some areas were tightly packed with townhouses (domus). The town had piped water[79] and a "fairly-sophisticated" drainage system.[80] The governor's palace was rebuilt[71] and an expanded forum was built around the earlier one over a period of 30 years from around 90 to 120 into an almost perfect square measuring 168 m × 167 m (551 ft × 548 ft).[66] Its three-storey basilica was probably visible across the city and was the largest in the empire north of the Alps;[66][81] the marketplace itself rivalled those in Rome and was the largest in the north before Augusta Treverorum (Trier, Germany) became an imperial capital.[82] The city's temple of Jupiter was renovated,[83] public and private bathhouses were erected, and a fort (arx) was erected around the year 120 that maintained the city garrison northwest of town.[84] The fort was square (with rounded corners) measuring more than 200 m × 200 m (660 ft × 660 ft) and covering more than 12 acres (4.9 ha). Each side had a central gatehouse and stone towers were erected at the corners and at points along each wall.[84] Londinium's amphitheatre, constructed in AD 70, is situated at Guildhall.[85]

When the Romans left in the 4th century, the amphitheatre lay derelict for hundreds of years. In the 11th century, the area was reoccupied, and by the 12th century the first Guildhall was built next to it.

A large port complex on both banks near London Bridge was discovered during the 1980s.

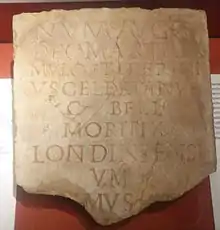

A temple complex with two Romano-British temples was excavated at Empire Square, Long Lane, Southwark in 2002/2003. A large house there may have been a guesthouse.

A marble slab with a dedication to the god Mars was discovered in the temple complex. The inscription mentions Londiniensi ('the Londoners'), the earliest known reference naming the people of London (photograph of the inscription above left).[86]

By the second half of the 2nd century, Londinium had many large, well-equipped stone buildings, some of which were richly adorned with wall paintings and floor mosaics, and had subfloor hypocausts. The Roman house at Billingsgate was built next to the waterfront and had its own bath.[87] In addition to such structures reducing the city's building density, however, Londinium also seems to have shrunk in both size and population in the second half of the 2nd century. The cause is uncertain but plague is considered likely, as the Antonine Plague is recorded decimating other areas of Western Europe between 165 and 190. The end of imperial expansion in Britain after Hadrian's decision to build his wall may have also damaged the city's economy.

Although Londinium remained important for the rest of the Roman period, no further expansion occurred. Londinium remained well populated, as archaeologists have found that much of the city after this date was covered in dark earth which accumulated relatively undisturbed over centuries.

London Wall

Some time between 190 and 225, the Romans built the London Wall, a defensive ragstone wall around the landward side of the city. Along with Hadrian's Wall and the road network, the London Wall was one of the largest construction projects carried out in Roman Britain. The wall was originally about 5 km (3 mi) long, 6 m (20 ft) high, and 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) thick. Its dry moat (fossa) was about 2 m (6 ft 7 in) deep and 3–5 m (9.8–16.4 ft) wide.[88] In the 19th century, Smith estimated its length from the Tower west to Ludgate at about one mile (1.6 km) and its breadth from the northern wall to the bank of the Thames at around half that.

In addition to small pedestrian postern gates like the one by Tower Hill, it had four main gates: Bishopsgate and Aldgate in the northeast at the roads to Eboracum (York) and to Camulodunum (Colchester) and Newgate and Ludgate in the west along at the road that divided for travel to Viroconium (Wroxeter) and to Calleva (Silchester) and at another road that ran along the Thames to the city's main cemetery and the old ford at Westminster. The wall partially utilised the army's existing fort, strengthening its outer wall with a second course of stone to match the rest of the course.[84][89] The fort had two gates of its own – Cripplegate to the north and another to the west – but these were not along major roads.[89] Aldersgate was eventually added, perhaps to replace the west gate of the fort. (The names of all these gates are medieval, as they continued to be occasionally refurbished and replaced until their demolition in the 17th and 18th centuries to permit widening the roads.)[89][90] The wall initially left the riverbank undefended: this was corrected in the 3rd century.

Although the exact reason for the wall's construction is unknown, some historians have connected it with the Pictish invasion of the 180s.[91] Others link it with Clodius Albinus, the British governor who attempted to usurp Septimius Severus in the 190s. The wall survived another 1,600 years and still roughly defines the City of London's perimeter.

3rd century

%252C_from_Walbrook_Mithraeum_in_Londinium%252C%252C_AD_180-220%252C_Museum_of_London_(14007820699).jpg.webp)

Septimius Severus defeated Albinus in 197 and shortly afterwards divided the province of Britain into Upper and Lower halves, with the former controlled by a new governor in Eboracum (York). Despite the smaller administrative area, the economic stimulus provided by the Wall and by Septimius Severus's campaigns in Caledonia somewhat revived London's fortunes in the early 3rd century. The northwest fort was abandoned and dismantled[84] but archaeological evidence points to renewed construction activity from this period. The London Mithraeum rediscovered in 1954 dates from around 240,[92] when it was erected on the east bank at the head of navigation on the now-covered River Walbrook about 200 m (660 ft) from the Thames.[93] From about 255 onwards, raiding by Saxon pirates led to the construction of a riverside wall as well. It ran roughly along the course of present-day Thames Street, which then roughly formed the shoreline. Large collapsed sections of this wall were excavated at Blackfriars and the Tower in the 1970s.[94]

Carausian Revolt

In 286, the emperor Maximian issued a death sentence against Carausius, admiral of the Roman navy's Britannic fleet (Classis Britannica), on charges of having abetted Frankish and Saxon piracy and of having embezzled recovered treasure. Carausius responded by consolidating his allies and territory and revolting. After fending off Maximian's first assault in 288, he declared a new Britannic Empire and issued coins to that effect. Constantius Chlorus's sack of his Gallic base at Gesoriacum (Boulogne), however, led his treasurer Allectus to assassinate and replace him. In 296, Chlorus mounted an invasion of Britain that prompted Allectus's Frankish mercenaries to sack Londinium. They were only stopped by the arrival of a flotilla of Roman warships on the Thames, which slaughtered the survivors.[95] The event was commemorated by the golden Arras Medallion, Chlorus on one side and, on the other, a woman kneeling at the city wall welcoming a mounted Roman soldier.[96] Another memorial to the return of Londinium to Roman control was the construction of a new set of forum baths around the year 300. The structures were modest enough that they were previously identified as parts of the forum and market but are now recognised as elaborate and luxurious baths including a frigidarium with two southern pools and an eastern swimming pool.

4th century

Following the revolt, the Diocletian Reforms saw the British administration restructured. Londinium is universally supposed to have been the capital of one of them, but it remains unclear where the new provinces were, whether there were initially three or four in total, and whether Valentia represented a fifth province or a renaming of an older one. In the 12th century, Gerald of Wales listed "Londonia" as the capital of Flavia, having had Britannia Prima (Wales) and Secunda (Kent) severed from the territory of Upper Britain.[97][98] Modern scholars more often list Londinium as the capital of Maxima Caesariensis on the assumption that the presence of the diocesan vicar in London would have required its provincial governor to outrank the others.

The governor's palace[71] and old large forum seem to have fallen out of use around 300,[81] but in general the first half of the 4th century appears to have been a prosperous time for Britain, for the villa estates surrounding London appear to have flourished during this period. The London Mithraeum was rededicated, probably to Bacchus. A list of the 16 "archbishops" of London was recorded by Jocelyne of Furness in the 12th century, claiming the city's Christian community was founded in the 2nd century under the legendary King Lucius and his missionary saints Fagan, Deruvian, Elvanus, and Medwin. None of that is considered credible by modern historians but, although the surviving text is problematic, either Bishop Restitutus or Adelphius at the 314 Council of Arles seems to have come from Londinium.[34] The location of Londinium's original cathedral is uncertain. The present structure of St Peter upon Cornhill was designed by Christopher Wren following the Great Fire in 1666 but it stands upon the highest point in the area of old Londinium and medieval legends tied it to the city's earliest Christian community. In 1995, however, a large and ornate 4th-century building on Tower Hill was discovered: built sometime between 350 and 400, it seems to have mimicked St Ambrose's cathedral in the imperial capital at Milan on a still-larger scale.[99] It was about 100 m (330 ft) long by about 50 m (160 ft) wide.[100] Excavations by David Sankey of MOLAS established it was constructed out of stone taken from other buildings, including a veneer of black marble.[99][101] It was probably dedicated to St Paul.[100]

From 340 onwards, northern Britain was repeatedly attacked by Picts and Gaels. In 360, a large-scale attack forced the emperor Julian the Apostate to send troops to deal with the problem. Large efforts were made to improve Londinium's defences around the same time. At least 22 semi-circular towers were added to the city walls to provide platforms for ballistae[89] and the present state of the river wall suggested hurried repair work around this time.[94] In 367, the Great Conspiracy saw a coordinated invasion of Picts, Gaels, and Saxons joined with a mutiny of troops along the Wall. Count Theodosius dealt with the problem over the next few years, using Londinium—then known as "Augusta"—as his base.[102] It may have been at this point that one of the existing provinces was renamed Valentia, although the account of Theodosius's actions describes it as a province recovered from the enemy.

In 382, Magnus Maximus organised all of the British-based troops and attempted to establish himself as emperor over the west. The event was obviously important to the Britons, as "Macsen Wledig" would remain a major figure in Welsh folklore and several medieval Welsh dynasties claimed descent from him. He was probably responsible for London's new church in the 370s or 380s.[99][100] He was initially successful but was defeated by Theodosius I at the 388 Battle of the Save. A new stretch of the river wall near Tower Hill seems to have been built further from the shore at some point over the next decade.[94]

5th century

With few troops left in Britain, many Romano-British towns—including Londinium—declined drastically over the next few decades. Many of London's public buildings had fallen into disrepair by this point, and excavations of the port show signs of rapid disuse.[73] Between 407 and 409, large numbers of barbarians overran Gaul and Hispania, seriously weakening communication between Rome and Britain. Trade broke down. Officials went unpaid and Romano-British troops elected their own leaders. Constantine III declared himself emperor over the West and crossed the Channel, an act considered the Roman withdrawal from Britain since the emperor Honorius subsequently directed the Britons to look to their own defence rather than send another garrison force.[103] Surviving accounts are scanty and mixed with Welsh and Saxon legends concerning Vortigern, Hengest, Horsa, and Ambrosius Aurelianus. Even archaeological evidence of Londinium during this period is minimal.

Despite remaining on the list of Roman provinces, Romano-Britain seems to have dropped their remaining loyalties to Rome. Raiding by the Irish, Picts, and Saxons continued but Gildas records a time of luxury and plenty[106] which is sometimes attributed to reduced taxation. Archaeologists have found evidence that a small number of wealthy families continued to maintain a Roman lifestyle until the middle of the 5th century, inhabiting villas in the southeastern corner of the city and importing luxuries.[103] Medieval accounts state that the invasions that established Anglo-Saxon England (the Adventus Saxonum) did not begin in earnest until some time in the 440s and 450s.[112] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded that the Britons fled to Londinium in terror after their defeat at the Battle of Crecganford (probably Crayford),[111] but nothing further is said. By the end of the 5th century, the city was largely an uninhabited ruin,[103] its large church on Tower Hill burnt to the ground.[99]

Over the next century, Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians arrived and established tribal areas and kingdoms. The area of the Roman city was administered as part of the Kingdom of the East Saxons – Essex, although the Saxon settlement of Lundenwic was not within the Roman walls but to the west in Aldwych. It was not until the Viking invasions of England that King Alfred the Great moved the settlement back within the safety of the Roman walls, which gave it the name Lundenburh. The foundations of the river wall, however, were undermined over time and had completely collapsed by the 11th century.[94] Memory of the earlier settlement survived: it is generally identified as the Cair Lundem[16] counted among the 28 cities of Britain included in the History of the Britons traditionally attributed to Nennius.[15][17]

Demographics

The population of Londinium is estimated to have peaked around 100 AD when it was still the capital of Britannia; at this point estimates for the population vary between about 30,000,[113] or about 60,000 people.[70] But there seems to have been a large decline after about 150 AD, possibly as the regional economic centres developed, and Londinium as the main port for imported goods became less significant. The Antonine Plague which swept the Empire from 165 to 180 may have had a big effect. Pottery workshops outside the city in Brockley Hill and Highgate appear to have ended production around 160, and the population may have fallen by as much as two thirds.[114]

Londinium was an ethnically diverse city with inhabitants from across the Roman Empire, including those with backgrounds from Britannia, continental Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.[115] A 2017 genetic test of human remains in Roman cemeteries states that the "presence of people born in London with North African ancestry is not an unusual or atypical result for Londinium."[116] A 2016 study of the isotope analysis of 20 bodies from various periods suggested that at least 12 had grown up locally, with four being immigrants, and the last four unclear.[117]

Excavation

Many ruins remain buried beneath London, although understanding them can be difficult. Owing to London's own geology, which consists of a Taplow Terrace deep bed of brickearth, sand, and gravel over clay,[118] Roman gravel roads can only be identified as such if they were repeatedly relayered or if the spans of gravel can be traced across several sites. The minimal remains from wooden structures are easy to miss and stone buildings may leave foundations, but – as with the great forum – they were often dismantled for stone during the Middle Ages and early modern period.[28]

The first extensive archaeological review of the Roman city of London was done in the 17th century after the Great Fire of 1666. Christopher Wren's renovation of St Paul's on Ludgate Hill found no evidence supporting Camden's contention[119] that it had been built over a Roman temple to the goddess Diana.[120] The extensive rebuilding of London in the 19th century and following the German bombing campaign during World War II also allowed for large parts of old London to be recorded and preserved while modern updates were made.[122] The construction of the London Coal Exchange led to the discovery of the Roman house at Billingsgate in 1848. In the 1860s, excavations by General Rivers uncovered a large number of human skulls and almost no other bones in the bed of the Walbrook.[123] The discovery recalls a passage in Geoffrey of Monmouth's pseudohistorical History of the Kings of Britain where Asclepiodotus besieged the last remnants of the usurper Allectus's army at "Londonia". Having battered the town's walls with siegeworks constructed by allied Britons, Asclepiodotus accepted the commander's surrender only to have the Venedotians rush upon them, ritually decapitating them and throwing the heads into the river "Gallemborne".[124][125] Asclepiodotus's siege was an actual event that occurred in AD 296, but further skull finds beneath the 3rd-century wall place at least some of the slaughter before its construction, leading most modern scholars to attribute them to Boudica's forces.[126][127] In 1947, the city's northwest fortress of the city garrison was discovered.[128] In 1954, excavations of what was thought to have been an early church instead revealed the London Mithraeum, which was relocated to permit building over its original site. The building erected at the time has since been demolished, and the temple has been returned to its former location under the new Bloomberg building.

Archaeologists began the first intensive excavation of the waterfront sites of Roman London in the 1970s. What was not found during this time has been built over, making it very difficult to study or discover anything new.[9] Another phase of archaeological work followed the deregulation of the London Stock Exchange in 1986, which led to extensive new construction in the city's financial district. From 1991, many excavations were undertaken by the Museum of London's Archaeology Service, although it was spun off into the separately-run MOLA in 2011 following legislation to address the Rose Theatre fiasco.

Displays

%252C_Museum_of_London_(14855574970).jpg.webp)

Major finds from Roman London, including mosaics, wall fragments, and old buildings, were formerly housed in the London and Guildhall Museums.[75] These merged after 1965[129] into the present Museum of London near the Barbican Centre. The Museum of London Docklands, a separate branch dealing with the history of London's ports, opened on the Isle of Dogs in 2003. Other finds from Roman London continue to be held in the British Museum.[75]

Much of the surviving wall is medieval, but Roman-era stretches are visible near Tower Hill tube station, in a hotel courtyard at nearby 8–10 Coopers Row, and in St Alphege Gardens off Wood Street.[89] A section of the river wall is visible inside the Tower of London.[94] Parts of the amphitheatre are on display beneath the Guildhall Art Gallery.[85] The southwestern tower of the Roman fort northwest of town can still be seen at Noble Street.[84] Occasionally, Roman sites are incorporated into the foundations of new buildings for future study, but these are not generally available to the public.[66][87]

See also

- Anglo-Saxon London

- Elizabethan London

Notes

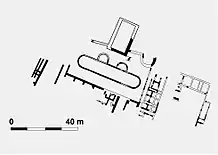

- Note that this image includes both the garrison fort, which was demolished in the 3rd century, and the Mithraeum, which was abandoned around the same time. The identification of the "governor's palace" remains conjectural.

- Hingley, Richard (9 August 2018). Londinium : a biography : Roman London from its origins to the fifth century. London. pp. 27–32. ISBN 978-1-350-04730-3. OCLC 1042078915.

- Hill, Julian. and Rowsome, Peter (2011). Roman London and the Walbrook stream crossing : excavations at 1 Poultry and vicinity, City of London. Rowsome, Peter., Museum of London Archaeology. London: Museum of London Archaeology. pp. 251–62. ISBN 978-1-907586-04-0. OCLC 778916833.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dunwoodie, Lesley. (2015). An early Roman fort and urban development on Londinium's eastern hill : excavations at Plantation Place, City of London, 1997-2003. Harward, Chiz., Pitt, Ken. London: MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology). ISBN 978-1-907586-32-3. OCLC 920542650.

- Marsden, Peter Richard Valentine. (1987). The Roman Forum Site in London : discoveries before 1985. Museum of London. London: H.M.S.O. ISBN 0-11-290442-4. OCLC 16415134.

- Bateman, Nick. (2008). London's Roman amphitheatre : Guildhall Yard, City of London. Cowan, Carrie., Wroe-Brown, Robin., Museum of London. Archaeology Service. [London]: Museum of London Archaeology Service. ISBN 978-1-901992-71-7. OCLC 276334521.

- Galfredus Monemutensis [Geoffrey of Monmouth]. Historia Regnum Britanniae [History of the Kings of Britain], Vol. III, Ch. xx. c. 1136. (in Latin)

- Geoffrey of Monmouth. Translated by J.A. Giles & al. as Geoffrey of Monmouth's British History, Vol. III, Ch. XX, in Six Old English Chronicles of Which Two Are Now First Translated from the Monkish Latin Originals: Ethelwerd's Chronicle, Asser's Life of Alfred, Geoffrey of Monmouth's British History, Gildas, Nennius, and Richard of Cirencester. Henry G. Bohn (London), 1848. Hosted at Wikisource.

- Haverfield, p. 145

- This etymology was first suggested in 1899 by d'Arbois de Jubainville and is generally accepted, as by Haverfield.[9]

- Jackson, Kenneth H. (1938). "Nennius and the 28 cities of Britain". Antiquity. 12 (45): 44–55. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00013405. S2CID 163506021.

- Coates, Richard (1998). "A new explanation of the name of London". Transactions of the Philological Society. 96 (2): 203–29. doi:10.1111/1467-968X.00027.

- This is the argument made by Jackson[11] and accepted by Coates.[12]

- Peter Schrijver, Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages (2013), p. 57.

- Ford, David Nash. "The 28 Cities of Britain Archived 15 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine" at Britannia. 2000.

- Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (in Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

- Newman, John Henry & al. Lives of the English Saints: St. German, Bishop of Auxerre, Ch. X: "Britain in 429, A. D.", p. 92. Archived 21 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine James Toovey (London), 1844.

- Bishop Ussher, cited in Newman[17]

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition. 1911.

- The London Archaeologist 1988 Vol 5 No. 14

- The Liberty of Southwark https://thedig.thelibertyofsouthwark.com/

- London's largest Roman mosaic find for 50 years uncovered https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-60466187

- White, Kevan (7 February 2016). "LONDINIVM AVGVSTA". roman-britain.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Tacitus. Ab Excessu Divi Augusti Historiarum Libri [Books of History from the Death of the Divine Augustus], Vol. XIV, Ch. XXXIII. c. AD 105. Hosted at Latin Wikisource. (in Latin)

- Latin: Londinium..., cognomento quidem coloniae non insigne, sed copia negotiatorum et commeatuum maxime celebre.[24]

- Tacitus. Translated by Alfred John Church & William Jackson Brodribb. Annals of Tacitus, Translated into English, with Notes and Maps, Book XIV, § 33. Macmillan & Co., London, 1876. Reprinted by Random House, 1942. Reprinted by the Perseus Project, c. 2011. Hosted at Wikisource.

- Merrifield, pp. 64–66.

- Merrifield, p. 68.

- Egbert, James. Introduction to the Study of Latin Inscriptions, p. 447. American Book Co. (Cincinnati),1896.

- Latin: P·P·BR·LON [Publicani Provinciae Britanniae Londinienses] & P·PR·LON [Publicani Provinciae Londinienses][29]

- Wacher, p. 85.

- Labbé, Philippe & Gabriel Cossart (eds.) Sacrosancta Concilia ad Regiam Editionem Exacta: quae Nunc Quarta Parte Prodit Actior [The Sancrosanct Councils Exacted for the Royal Edition: which the Editors Now Produce in Four Parts], Vol. I: "Ab Initiis Æræ Christianæ ad Annum CCCXXIV" ["From the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Year 324"], col. 1429. The Typographical Society for Ecclesiastical Books (Paris), 1671. (in Latin)

- Thackery, Francis. Researches into the Ecclesiastical and Political State of Ancient Britain under the Roman Emperors: with Observations upon the Principal Events and Characters Connected with the Christian Religion, during the First Five Centuries, pp. 272 ff. T. Cadell (London), 1843. (in Latin and English)

- "Nomina Episcoporum, cum Clericis Suis, Quinam, et ex Quibus Provinciis, ad Arelatensem Synodum Convenerint" ["The Names of the Bishops with Their Clerics who Came Together at the Synod of Arles and from which Province They Came"] from the Consilia[32] in Thackery[33]

- "Living in Roman London: From Londinium to London". London: The Museum of London. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- Hingley, Introduction

- Wright, Thomas (1852). The Celt, the Roman, and the Saxon: A history of the early inhabitants of Britain, down to the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. London: Arthur Hall, Virtue & Co. p. 95.

- Perring, Dominic (2011). "Two studies on Roman London. A: London's military origins. B: Population decline and ritual landscapes in Antonine London". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 24: 249–282. doi:10.1017/S1047759400003378. ISSN 1047-7594. S2CID 160758496.

- Wallace, Lacey (2013). "The Foundation of Roman London: Examining the Claudian Fort Hypothesis". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 32 (3): 275–291. doi:10.1111/ojoa.12015. ISSN 1468-0092.

- Wallace, Leslie (2015). The Origin of Roman London. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-107-04757-0. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Hingley, start of Introduction

- Merrifield, p. 40.

- It may have spanned the tidal limit of the Thames at the time, with the port in tidal waters and the bridge upstream beyond its reach.[42] This is uncertain, however: in the Middle Ages, the Thames's tidal reach extended to Staines and today it still reaches Teddington.

- Togodumnus (2011). "Londinivm Avgvsta: Provincial Capital". Roman Britain. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Wacher, pp. 88–90.

- Number 1 Poultry (ONE 94), Museum of London Archaeology, 2013. Archaeology Data Service, The University of York.

- Antonine Itinerary. British Routes. Routes 2, 3, & 4.

- Although three of them used the same route into town.[47]

- "Public life: All roads lead to Londinium". Museum of London Group. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- Margary, Ivan Donald (1967). Roman Roads in Britain (2nd ed.). London: John Baker. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-319-22942-2.

- Perring, Dominic (1991). Roman London: The Archaeology of London. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-415-62010-9.

- Fearnside, William Gray; Harral, Thomas (1838). The History of London: Illustrated by Views of London and Westminster. Illustrated by John Woods. London: Orr & Co. p. 15.

- Sheppard, Francis (1998). London: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-19-822922-3.

- Merrifield, Ralph (1983). London, City of the Romans. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 116–119. ISBN 978-0-520-04922-2.

- Merrifield, pp. 32–33.

- Margary,[50] cited by Perring,[51] although he notes that this remains conjectural: the known roads would not meet at the river if continued in a straight line,[51] there is no evidence textual or archaeological at the moment for a ford at Westminster,[51] and the Saxon ford was further upstream at Kingston.[52] Against such doubts, Sheppard notes the known routes broadly direct towards Westminster in a way "inconceivable" if they were meant to be directed towards a ferry at Londinium[53] and Merrifield points to routes directed towards the presumed ford from Southwark.[54] Both include maps of the known routes around London and their proposed reconstruction of major connections now-lost.[53][54][55]

- Tacitus, Annals, 12.31.

- H. H. Scullard, From the Gracchi to Nero, 1982, p. 90

- John Morris, Londinium: London in the Roman Empire, 1982, pp. 107–108

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 62.2

- Tacitus, Annals, 14.31

- Merrifield, p. 53.

- "Highbury, Upper Holloway and King's Cross", Old and New London: Volume 2 (1878:273–279). Date accessed: 26 December 2007.

- An early Roman fort and urban development on Londinium's eastern hill: excavations at Plantation Place, City of London, 1997–2003, L. Dunwoodie et al. MOLA 2015. ISBN 978-1-907586-32-3

- Merrifield, pp. 66–68.

- "Londinium Today: Basilica and forum". Museum of London Group. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- Merrifield, p. 62.

- Merrifield, pp. 63–64.

- Will Durant (7 June 2011). Caesar and Christ: The Story of Civilization. Simon and Schuster. p. 468. ISBN 978-1-4516-4760-0.

- Anne Lancashire (2002). London Civic Theatre: City Drama and Pageantry from Roman Times to 1558. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-63278-2.

- Marsden, Peter (1975). "The Excavation of a Roman Palace Site in London". Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. 26: 1–102.

- Emerson, Giles (2003). City of Sin: London in Pursuit of Pleasure. Carlton Books. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-1-84222-901-9.

- Milne.

- Brigham.

- Hall & Merrifield.

- Hingley, Richard (9 August 2018). Londinium : a biography : Roman London from its origins to the fifth century. Unwin, Christina. London. pp. 116–120. ISBN 978-1-350-04730-3. OCLC 1042078915.

- Hill, Julian and Rowsome, P. (2011). Roman London and the Walbrook stream crossing : excavations at 1 Poultry and vicinity, City of London. Rowsome, Peter., Museum of London Archaeology. London: Museum of London Archaeology. pp. 354–7. ISBN 978-1-907586-04-0. OCLC 778916833.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Perring, Dominic (November 2017). "London's Hadrianic War?". Britannia. 48: 37–76. doi:10.1017/S0068113X17000113. ISSN 0068-113X.

- Fields, Nic (2011). Campaign 233: Boudicca's Rebellion AD 60–61: The Britons rise up against Rome. Illustrated by Peter Dennis. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84908-313-3.

- Merrifield, p. 50.

- P. Marsden (1987). The Roman Forum Site in London: Discoveries before 1985. ISBN 978-0-11-290442-7.

- Merrifield, p. 68.

- According to a recovered inscription. The location of the Temple of Jupiter has not been discovered yet.

- "Londinium Today: The fort". Museum of London Group. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "Londinium Today: The amphitheatre". Museum of London Group. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- Roman London Fragments, Cosmetic Cream And Bikini Bottoms

- "Londinium Today: House and baths at Billingsgate". Museum of London Group. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- Lepage, Jean-Denis G.G. (2012). British Fortifications through the Reign of Richard III: An Illustrated History. Jefferson: McFarland & Co. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-7864-5918-6.

- "Visible Roman London: City wall and gates". Museum of London Group. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- In the 1170s, William FitzStephen mentioned seven gates in London's landward wall, but it's not clear whether this included a minor postern gate or another, now unknown, major gate. Moorgate was later counted as a seventh major gate after its enlargement in 1415, but in William's time it would have been a minor postern gate.[89]

- "Timeline of Romans in Britain". Channel4.com. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- "Visible Roman London: Temple of Mithras". Museum of London Group. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- Trench, Richard; Hillman Ellis (1985). London under London: a subterranean guide. John Murray (publishers) Ltd. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-0-7195-4080-6.

- "Londinium Today: Riverside wall". Museum of London Group. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- Eumenius.

- The medallion is named for its mint mark from Augusta Treverorum (Trier); it was discovered in Arras, France, in the 1920s.

- Giraldus Cambriensis [Gerald of Wales]. De Inuectionibus [On Invectives], Vol. II, Ch. I, in Y Cymmrodor: The Magazine of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, Vol. XXX, pp. 130–31. George Simpson & Co. (Devizes), 1920. (in Latin)

- Gerald of Wales. Translated by W.S. Davies as The Book of Invectives of Giraldus Cambrensis in Y Cymmrodor: The Magazine of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, Vol. XXX, p. 16. George Simpson & Co. (Devizes), 1920.

- Denison, Simon (June 1995). "News: In Brief". British Archaeology. Council for British Archaeology. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- Keys, David (3 April 1995). "Archaeologists unearth capital's first cathedral: Giant edifice built out of secondhand masonry". The Independent. London.

- Sankey, D. (1998). "Cathedrals, granaries and urban vitality in late Roman London". In Watson, Bruce (ed.). Roman London: Recent Archaeological Work. JRA Supplementary Series. Vol. 24. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology. pp. 78–82.

- Riddell, Jim. "The status of Roman London". Archived from the original on 24 April 2008.

- "Roman London: A Brief History". Museum of London. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009.

- Giles, John Allen (ed. & trans.). "The Works of Gildas, Surnamed 'Sapiens,' or the Wise" in Six Old English Chronicles of Which Two Are Now First Translated from the Monkish Latin Originals: Ethelwerd's Chronicle, Asser's Life of Alfred, Geoffrey of Monmouth's British History, Gildas, Nennius, and Richard of Cirencester. Henry G. Bohn (London), 1848.

- Habington, Thomas (trans.). The Epistle of Gildas the most ancient British Author: who flourished in the yeere of our Lord, 546. And who by his great erudition, sanctitie, and wisdome, acquired the name of Sapiens. Faithfully translated out of the originall Latine in 8 vols. T. Cotes for William Cooke (London), 1638.

- The Ruin of Britain, Ch. 22 ff, John Allen Giles's revision[104] of Thomas Habington's translation,[105] hosted at Wikisource.

- Jones, Michael E.; Casey, John (1988), "The Gallic Chronicle Restored: a Chronology for the Anglo-Saxon Invasions and the End of Roman Britain", Britannia, XIX (November): 367–98, doi:10.2307/526206, JSTOR 526206, S2CID 163877146, archived from the original on 13 March 2020, retrieved 6 January 2014

- Anderson, Alan Orr (October 1912). Watson, Mrs W.J. (ed.). "Gildas and Arthur". The Celtic Review (published 1913). VIII (May 1912 – May 1913) (30): 149–165. doi:10.2307/30070428. JSTOR 30070428.

- Beda Venerabilis [The Venerable Bede]. Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum [The Ecclesiastical History of the English People], Vol. I, Ch. XV, & Vol. V, Ch. XXIIII. 731. Hosted at Latin Wikisource. (in Latin)

- Bede. Translated by Lionel Cecil Jane as The Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, Vol. 1, Ch. 15, & Vol. 5, Ch. 24. J.M. Dent & Co. (London), 1903. Hosted at Wikisource.

- Anonymous. Translated by James Ingram. The Saxon Chronicle, with an English Translation, and Notes, Critical and Explanatory. To Which Are Added Chronological, Topographical, and Glossarial Indices; a Short Grammar of the Anglo-Saxon Language; a New Map of England during the Heptarchy; Plates of Coins, &c., p. 15., "An. CCCCLV." Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown (London), 1823. (in Old English and English)

- The near-contemporary 452 Gallic Chronicle recorded that "The British provinces, which to this time had suffered various defeats and misfortunes, are reduced to Saxon rule" in the year 441;[107] Gildas described a revolt of Saxon foederati[106] but his dating is obscure;[108] Bede dates it to a few years after 449 and opines that invasion had been the Saxons' intention from the beginning;[109][110] the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle dates the revolt to 455.[111]

- Sheppard, 35, google books

- Sheppard, 35-36

- DNA study finds London was ethnically diverse from start, BBC, 23 November 2015

- Poinar, Hendrik N.; Eaton, Katherine; Marshall, Michael; Redfern, Rebecca C. (2017). "'Written in Bone': New Discoveries about the Lives and Burials of Four Roman Londoners". Britannia. 48: 253–277. doi:10.1017/S0068113X17000216. ISSN 0068-113X.

- Janet Montgomery, Rebecca Redfern, Rebecca Gowland, Jane Evans, Identifying migrants in Roman London using lead and strontium stable isotopes, 2016, Journal of Archaeological Science

- Grimes, Ch. I.

- Camden, William (1607), Britannia (in Latin), London: G. Bishop & J. Norton, pp. 306–7

- Clark, John (1996). "The Temple of Diana". In Bird, Joanna; et al. (eds.). Interpreting Roman London. Oxbow Monograph. Vol. 58. Oxford: Oxbow. pp. 1–9.

- Grimes, William Francis (1968). "Map of the walled city of London showing areas devastated by bombing, with sites excavated by the Excavation Council". The Excavation of Roman and Mediaeval London. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-60471-6.

- For a map of the locations of bombed sites in the City of London excavated by the Society of Antiquaries of London's Roman and Medieval London Excavation Council during this period, see Grimes.[121]

- Thorpe, Lewis. The History of the Kings of Britain, p. 19. Penguin, 1966.

- Galfredus Monemutensis [Geoffrey of Monmouth]. Historia Regnum Britanniae [History of the Kings of Britain], Vol. V, Ch. iv. c. 1136. (in Latin)

- Geoffrey of Monmouth. Translated by J.A. Giles & al. as Geoffrey of Monmouth's British History, Vol. V, Ch. IV, in Six Old English Chronicles of Which Two Are Now First Translated from the Monkish Latin Originals: Ethelwerd's Chronicle, Asser's Life of Alfred, Geoffrey of Monmouth's British History, Gildas, Nennius, and Richard of Cirencester. Henry G. Bohn (London), 1848. Hosted at Wikisource.

- Merrifield, p. 57.

- Morris, John. Londinium: London in the Roman Empire, p. 111. 1982.

- Grimes, Ch. II, § 2.

- "Museum of London Act 1965". legislation.gov.uk. National Archives. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

References

- Billings, Malcolm (1994), London: a companion to its history and archaeology, ISBN 1-85626-153-0

- Brigham, Trevor. 1998. “The Port of Roman London.” In Roman London Recent Archeological Work, edited by B. Watson, 23–34. Michigan: Cushing–Malloy Inc. Paper read at a seminar held at The Museum of London, 16 November.

- Hall, Jenny, and Ralph Merrifield. Roman London. London: HMSO Publications, 1986.

- Haverfield, F. "Roman London." The Journal of Roman Studies 1 (1911): 141–72.

- Hingley, Richard, Londinium: A Biography: Roman London from its Origins to the Fifth Century, 2018, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 1350047317, 9781350047310

- Inwood, Stephen. A History of London (1998) ISBN 0-333-67153-8

- John Wacher: The Towns of Roman Britain, London/New York 1997, p. 88–111. ISBN 0-415-17041-9

- Gordon Home: Roman London: A.D. 43–457 Illustrated with black and white plates of artefacts. diagrams and plans. Published by Eyre and Spottiswoode (London) in 1948 with no ISBN.

- Milne, Gustav. The Port of Roman London. London: B.T. Batsford, 1985.

- Sheppard, Francis, London: A History, 2000, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0192853694, 9780192853691, google books

Further reading

External links

- Roman London, History of World Cities

- Roman London, Encyclopædia Britannica

- A map of known and conjectural Roman roads around Londinium, from London: A History

- The eastern cemetery of Roman London: excavations 1983–90, Museum of London Archive