Sarin

Sarin (NATO designation GB [short for G-series, "B"]) is an extremely toxic synthetic organophosphorus compound.[4] A colourless, odourless liquid, it is used as a chemical weapon due to its extreme potency as a nerve agent. Exposure is lethal even at very low concentrations, where death can occur within one to ten minutes after direct inhalation of a lethal dose,[5][6] due to suffocation from respiratory paralysis, unless antidotes are quickly administered.[4] People who absorb a non-lethal dose and do not receive immediate medical treatment may suffer permanent neurological damage .

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈsɑːrɪn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name

Propan-2-yl methylphosphonofluoridate | |

| Other names

(RS)-O-Isopropyl methylphosphonofluoridate; IMPF; GB;[2] 2-(Fluoro-methylphosphoryl)oxypropane; Phosphonofluoridic acid, P-methyl-, 1-methylethyl ester | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H10FO2P | |

| Molar mass | 140.094 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Clear colourless liquid, brownish if impure |

| Odor | Odourless in pure form. Impure sarin can smell like mustard or burned rubber. |

| Density | 1.0887 g/cm3 (25 °C) 1.102 g/cm3 (20 °C) |

| Melting point | −56 °C (−69 °F; 217 K) |

| Boiling point | 158 °C (316 °F; 431 K) |

| Miscible | |

| log P | 0.30 |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

Extremely lethal cholinergic agent. |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Threshold limit value (TLV) |

0.00003 mg/m3 (TWA), 0.0001 mg/m3 (STEL) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

39 μg/kg (intravenous, rat)[3] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

0.1 mg/m3 |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | Lethal Nerve Agent Sarin (GB) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Sarin is widely considered a weapon of mass destruction. Production and stockpiling of sarin was outlawed as of April 1997 by the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993, and it is classified as a Schedule 1 substance.

Health effects

Like some other nerve agents that affect the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, sarin attacks the nervous system by interfering with the degradation of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine at neuromuscular junctions. Death will usually occur as a result of asphyxia due to the inability to control the muscles involved in breathing.

Initial symptoms following exposure to sarin are a runny nose, tightness in the chest, and constriction of the pupils. Soon after, the person will have difficulty breathing and they will experience nausea and drooling. As they continue to lose control of bodily functions, they may vomit, defecate, and urinate. This phase is followed by twitching and jerking. Ultimately, the person becomes comatose and suffocates in a series of convulsive spasms. Moreover, common mnemonics for the symptomatology of organophosphate poisoning, including sarin, are the "killer Bs" of bronchorrhea and bronchospasm because they are the leading cause of death,[7] and SLUDGE – salivation, lacrimation, urination, defecation, gastrointestinal distress, and emesis (vomiting). Death may follow in one to ten minutes after direct inhalation.

Sarin has a high volatility (ease with which a liquid can turn into vapour) relative to similar nerve agents, making inhalation very easy, and may even absorb through the skin. A person's clothing can release sarin for about 30 minutes after it has come in contact with sarin gas, which can lead to exposure of other people.[8]

Management

Treatment measures have been described.[8] Treatment is typically with the antidotes atropine and pralidoxime.[4] Atropine, an antagonist to muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, is given to treat the physiological symptoms of poisoning. Since muscular response to acetylcholine is mediated through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, atropine does not counteract the muscular symptoms. Pralidoxime can regenerate cholinesterases if administered within approximately five hours. Biperiden, a synthetic acetylcholine antagonist, has been suggested as an alternative to atropine due to its better blood–brain barrier penetration and higher efficacy.[9]

Mechanism of action

Sarin is a potent inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase,[10] an enzyme that degrades the neurotransmitter acetylcholine after it is released into the synaptic cleft. In vertebrates, acetylcholine is the neurotransmitter used at the neuromuscular junction, where signals are transmitted between neurons from the central nervous system to muscle fibres. Normally, acetylcholine is released from the neuron to stimulate the muscle, after which it is degraded by acetylcholinesterase, allowing the muscle to relax. A build-up of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft, due to the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, means the neurotransmitter continues to act on the muscle fibre, so that any nerve impulses are effectively continually transmitted.

Sarin acts on acetylcholinesterase by forming a covalent bond with the particular serine residue at the active site. Fluoride is the leaving group, and the resulting organo-phosphoester is robust and biologically inactive.[11][12]

Its mechanism of action resembles that of some commonly used insecticides, such as malathion. In terms of biological activity, it resembles carbamate insecticides, such as Sevin, and the medicines pyridostigmine, neostigmine, and physostigmine.

Diagnostic tests

Controlled studies in healthy men have shown that a nontoxic 0.43 mg oral dose administered in several portions over a 3-day interval caused average maximum depressions of 22 and 30%, respectively, in plasma and erythrocyte acetylcholinesterase levels. A single acute 0.5 mg dose caused mild symptoms of intoxication and an average reduction of 38% in both measures of acetylcholinesterase activity. Sarin in blood is rapidly degraded either in vivo or in vitro. Its primary inactive metabolites have in vivo serum half-lives of approximately 24 hours. The serum level of unbound isopropyl methylphosphonic acid (IMPA), a sarin hydrolysis product, ranged from 2–135 μg/L in survivors of a terrorist attack during the first four hours post-exposure. Sarin or its metabolites may be determined in blood or urine by gas or liquid chromatography, while acetylcholinesterase activity is usually measured by enzymatic methods.[13]

A newer method called "fluoride regeneration" or "fluoride reactivation" detects the presence of nerve agents for a longer period after exposure than the methods described above. Fluoride reactivation is a technique that has been explored since at least the early 2000s. This technique obviates some of the deficiencies of older procedures. Sarin not only reacts with the water in the blood plasma through hydrolysis (forming so-called 'free metabolites'), but also reacts with various proteins to form 'protein adducts'. These protein adducts are not so easily removed from the body, and remain for a longer period of time than the free metabolites. One clear advantage of this process is that the period, post-exposure, for determination of sarin exposure is much longer, possibly five to eight weeks according to at least one study.[14][15]

Toxicity

As a nerve gas, sarin in its purest form is estimated to be 26 times more deadly than cyanide.[16] The [[LD50]] of subcutaneously injected sarin in mice is 172 μg/kg.[17]

Sarin is highly toxic, whether by contact with the skin or breathed in. The toxicity of sarin in humans is largely based on calculations from studies with animals. The lethal concentration of sarin in air is approximately 28–35 mg per cubic meter per minute for a two-minute exposure time by a healthy adult breathing normally (exchanging 15 liters of air per minute, lower 28 mg/m3 value is for general population).[18] This number represents the estimated lethal concentration for 50% of exposed victims, the LCt50 value. The LCt95 or LCt100 value is estimated to be 40–83 mg per cubic meter for exposure time of two minutes.[19][20] Calculating effects for different exposure times and concentrations requires following specific toxic load models. In general, brief exposures to higher concentrations are more lethal than comparable long time exposures to low concentrations.[21] There are many ways to make relative comparisons between toxic substances. The list below compares sarin to some current and historic chemical warfare agents, with a direct comparison to the respiratory LCt50:

- Hydrogen cyanide, 2,860 mg·min/m2[22] – Sarin is 81 times more lethal

- Phosgene, 1,500 mg·min/m2[22] – Sarin is 43 times more lethal

- Sulfur mustard, 1,000 mg·min/m2[22] – Sarin is 28 times more lethal

- Chlorine, 19,000 mg·min/m2[23] – Sarin is 543 times more lethal

Production and structure

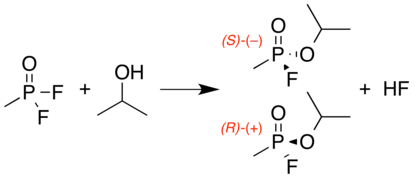

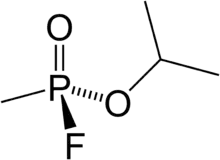

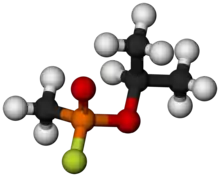

Sarin is a chiral molecule because it has four chemically distinct substituents attached to the tetrahedral phosphorus center.[24] The SP form (the (–) optical isomer) is the more active enantiomer due to its greater binding affinity to acetylcholinesterase.[25][26] The P-F bond is easily broken by nucleophilic agents, such as water and hydroxide. At high pH, sarin decomposes rapidly to nontoxic phosphonic acid derivatives.[27]

It is almost always manufactured as a racemic mixture (a 1:1 mixture of its enantiomeric forms) as this involves a much simpler synthetic process whilst providing an adequate weapon.[25][26]

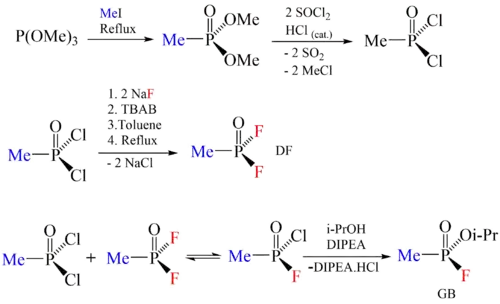

A number of production pathways can be used to create sarin. The final reaction typically involves attachment of the isopropoxy group to the phosphorus with an alcoholysis with isopropyl alcohol. Two variants of this process are common. One is the reaction of methylphosphonyl difluoride with isopropyl alcohol, which produces a racemic mixture of sarin enantiomers with hydrofluoric acid as a byproduct:[27]

The second process, known as the "Di-Di" process, uses equal quantities of methylphosphonyl difluoride (Difluoro) and methylphosphonyl dichloride (Dichloro), rather than just the difluoride. This reaction also gives sarin, but hydrochloric acid as a byproduct instead. The Di-Di process was used by the United States for the production of its unitary sarin stockpile.[27]

The scheme below shows a generic example of the Di-Di process; in reality, the selection of reagents and reaction conditions dictate both product structure and yield. The choice of enantiomer of the mixed chloro fluoro intermediate displayed in the diagram is arbitrary, but the final substitution is selective for chloro over fluoro as the leaving group. Inert atmosphere and anhydrous conditions (Schlenk techniques) are used for synthesis of sarin and other organophosphates.[27]

As both reactions leave considerable acid in the product, sarin produced in bulk by these methods has a short half life without further processing, and would be corrosive to containers and damaging to weapons systems. Various methods have been tried to resolve these problems. In addition to industrial refining techniques to purify the chemical itself, various additives have been tried to combat the effects of the acid, such as:

- Tributylamine was added to US sarin produced at Rocky Mountain Arsenal.[28]

- Triethylamine was added to UK sarin, with relatively poor success.[29] The Aum Shinrikyo cult experimented with triethylamine as well.[30]

- N,N-Diethylaniline was used by Aum Shinrikyo for acid reduction.[31]

- N,N′-Diisopropylcarbodimide was added to sarin produced at Rocky Mountain Arsenal to combat corrosion.[32]

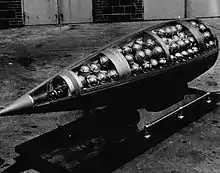

- Isopropylamine was included as part of the M687 155 mm field artillery shell, which was a binary sarin weapon system developed by the US Army.[33]

Another byproduct of these two chemical processes is diisopropyl methylphosphonate, formed when a second isopropyl alcohol reacts with the sarin itself and from disproportionation of sarin, when distilled incorrectly. The factor of its formation in esterification is that as the concentration of DF-DCl decreases, the concentration of sarin increases, the probability of DIMP formation is greater. DIMP is a natural impurity of sarin, that is almost impossible to be eliminated, mathematically, when the reaction is a 1 mol-1 mol "one-stream".[34]

This chemical degrades into isopropyl methylphosphonic acid.[35]

Degradation and shelf life

The most important chemical reactions of phosphoryl halides is the hydrolysis of the bond between phosphorus and the fluoride. This P-F bond is easily broken by nucleophilic agents, such as water and hydroxide. At high pH, sarin decomposes rapidly to nontoxic phosphonic acid derivatives.[36][37] The initial breakdown of sarin is into isopropyl methylphosphonic acid (IMPA), a chemical that is not commonly found in nature except as a breakdown product of sarin (this is useful for detecting the recent deployment of sarin as a weapon). IMPA then degrades into methylphosphonic acid (MPA), which can also be produced by other organophosphates.[38]

Sarin with residual acid degrades after a period of several weeks to several months. The shelf life can be shortened by impurities in precursor materials. According to the CIA, some Iraqi sarin had a shelf life of only a few weeks, owing mostly to impure precursors.[39]

Along with nerve agents such as tabun and VX, sarin can have a short shelf life. Therefore, it is usually stored as two separate precursors that produce sarin when combined.[40] Sarin's shelf life can be extended by increasing the purity of the precursor and intermediates and incorporating stabilizers such as tributylamine. In some formulations, tributylamine is replaced by diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC), allowing sarin to be stored in aluminium casings. In binary chemical weapons, the two precursors are stored separately in the same shell and mixed to form the agent immediately before or when the shell is in flight. This approach has the dual benefit of solving the stability issue and increasing the safety of sarin munitions.

History

Sarin was discovered in 1938 in Wuppertal-Elberfeld in Germany by scientists at IG Farben who were attempting to create stronger pesticides; it is the most toxic of the four G-Series nerve agents made by Germany. The compound, which followed the discovery of the nerve agent tabun, was named in honor of its discoverers: chemist Gerhard Schrader, chemist Otto Ambros, chemist Gerhard Ritter, and from Heereswaffenamt Hans-Jürgen von der Linde.[41]

Use as a weapon

In mid-1939, the formula for the agent was passed to the chemical warfare section of the German Army Weapons Office, which ordered that it be brought into mass production for wartime use. Pilot plants were built, and a high-production facility was under construction (but was not finished) by the end of World War II. Estimates for total sarin production by Nazi Germany range from 500 kg to 10 tons.[42]

Though sarin, tabun and soman were incorporated into artillery shells, Germany did not use nerve agents against Allied targets. Adolf Hitler refused to initiate the use of gases such as sarin as weapons.[43]

- 1950s (early): NATO adopted sarin as a standard chemical weapon, and both the USSR and the United States produced sarin for military purposes.

- 1953: 20-year-old Ronald Maddison, a Royal Air Force engineer from Consett, County Durham, died in human testing of sarin at the Porton Down chemical warfare testing facility in Wiltshire, England. Ten days after his death an inquest was held in secret which returned a verdict of misadventure. In 2004, the inquest was reopened and, after a 64-day inquest hearing, the jury ruled that Maddison had been unlawfully killed by the "application of a nerve agent in a non-therapeutic experiment".[44]

- 1957: Regular production of sarin chemical weapons ceased in the United States, though existing stocks of bulk sarin were re-distilled until 1970.[28]

- 1976: Chile's intelligence service, DINA, assigned biochemist Eugenio Berríos to develop Sarin gas within its program Proyecto Andrea, to be used as a weapon against its opponents.[45] One of DINA's goals was to package it in spray cans for easy use, which, according to testimony by former DINA agent Michael Townley, was one of the planned procedures in the 1976 assassination of Orlando Letelier.[45] Berríos later testified that it was used in a number of assassinations and it was planned to be used to kill inhabitants, through poisoning the water supply of Argentine capital Buenos Aires, in case Operation Soberanía took place.[46][47]

- March 1988: Halabja chemical attack; Over two days in March, the ethnic Kurdish city of Halabja in northern Iraq (population 70,000) was bombarded by Saddam Hussein's Iraqi Air Force jets with chemical bombs including sarin. An estimated 5,000 people died, almost all civilians.[48]

- April 1988: Sarin was used four times against Iranian soldiers at the end of the Iran–Iraq War, helping Iraqi forces to retake control of the al-Faw Peninsula during the Second Battle of al-Faw.

- 1993: The United Nations Chemical Weapons Convention was signed by 162 member countries, banning the production and stockpiling of many chemical weapons, including sarin. It went into effect on April 29, 1997, and called for the complete destruction of all specified stockpiles of chemical weapons by April 2007.[49] When the convention entered force, the parties declared worldwide stockpiles of 15,047 tonnes of sarin. As of November 28th, 2019, 98% of the stockpiles have been destroyed.[50]

- 1994: Matsumoto incident; the Japanese religious sect Aum Shinrikyo released an impure form of sarin in Matsumoto, Nagano, killing eight people and harming over 500. The Australian sheep station Banjawarn was a testing ground.

- 1995: Tokyo subway sarin attack; the Aum Shinrikyo sect released an impure form of sarin in the Tokyo Metro. Twelve people died, and over 6,200 people received injuries.[51][52]

- 2002: Pro-Chechen militant Ibn al-Khattab may have been assassinated with sarin by the Russian government.[53][54]

- May 2004: Iraqi insurgents detonated a 155 mm shell containing binary precursors for sarin near a U.S. convoy in Iraq. The shell was designed to mix the chemicals as it spun during flight. The detonated shell released only a small amount of sarin gas, either because the explosion failed to mix the binary agents properly or because the chemicals inside the shell had degraded with age. Two United States soldiers were treated after displaying the early symptoms of exposure to sarin.[55]

- March 2013: Khan al-Assal chemical attack; Sarin was used in an attack on a town west of Aleppo city in Syria, killing 28 and wounding 124.[56]

- August 2013: Ghouta chemical attack; Sarin was used in multiple simultaneous attacks in the Ghouta region of the Rif Dimashq Governorate of Syria during the Syrian Civil War.[57] Varying[58] sources gave a death toll of 322[59] to 1,729.[60]

- April 2017: Khan Shaykhun chemical attack; Sarin gas was released in rebel-held Idlib Province in Syria by the Syrian Air Force during an airstrike.[61][62]

- April 2018: Douma chemical attack victims reported to have symptoms consistent with exposure to sarin and other agents. On 6 July 2018, the Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) of the OPCW published their interim report. The report stated that, "The results show that no organophosphorous [sarin] nerve agents or their degradation products were detected in the environmental samples or in the plasma samples taken from alleged casualties". The chemical agent used in the attack was later identified as elemental chlorine.[63]

See also

- Chlorosarin

- Ethylsarin

- Thiosarin

- Gulf War syndrome

References

- "Material Safety Data Sheet -- Lethal Nerve Agent Sarin (GB)". 103d Congress, 2d Session. United States Senate. May 25, 1994. Retrieved November 6, 2004.

- "Sarin". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- "Substance Name: Sarin". ChemIDplus. U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- Sarin (GB). Emergency Response Safety and Health Database. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Accessed April 20, 2009.

- Anderson, Kenneth (September 17, 2013). A Poisonous Affair: America, Iraq, and the Gassing of Halabja review of A Poisonous Affair: America, Iraq, and the Gassing of Halabja by Joost R. Hiltermann (Cambridge UP 2007). Lawfare: Hard National Security Choices (Report). Retrieved December 30, 2015.

... death can occur within one minute of direct inhalation as the lung muscles are paralyzed.

- Smith, Michael (August 26, 2002). "Saddam to be target of Britain's 'E-bomb'". The Daily Telegraph. p. A18. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

The nerve agents sarin and VX. Colourless and tasteless, they cause death by respiratory arrest in one to 15 minutes.

- Gussow, Leon (July 2005). "Nerve Agents: Three Mechanisms, Three Antidotes". Emergency Medicine News. Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer. 27 (7): 12. doi:10.1097/00132981-200507000-00011.

- "Facts About Sarin". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 18, 2015. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- Shim, TM; McDonough JH (May 2000). "Efficacy of biperiden and atropine as anticonvulsant treatment for organophosphorus nerve agent intoxication" (PDF). Archives of Toxicology. 74 (3): 165–172. doi:10.1007/s002040050670. PMID 10877003. S2CID 13749842. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- Abu-Qare AW, Abou-Donia MB (October 2002). "Sarin: health effects, metabolism, and methods of analysis". Food and Chemical Toxicology. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. 40 (10): 1327–33. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00079-0. PMID 12387297.

- Millard CB, Kryger G, Ordentlich A, et al. (June 1999). "Crystal Structures of Aged Phosphonylated Acetylcholinesterase: Nerve Agent Reaction Products at the Atomic Level". Biochemistry. 38 (22): 7032–9. doi:10.1021/bi982678l. PMID 10353814. S2CID 11744952.. See Proteopedia 1cfj.

- Hörnberg, Andreas; Tunemalm, Anna-Karin; Ekström, Fredrik (2007). "Crystal Structures of Acetylcholinesterase in Complex with Organophosphorus Compounds Suggest that the Acyl Pocket Modulates the Aging Reaction by Precluding the Formation of the Trigonal Bipyramidal Transition State". Biochemistry. 46 (16): 4815–4825. doi:10.1021/bi0621361. PMID 17402711.

- Baselt, Randall C.; Cravey, Robert H. (2017). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man. Seal Beach, California: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1926–1928. ISBN 978-0-8151-0547-3.

- Jakubowski; et al. (July 2003). Fluoride ion regeneration of sarin (GB) from minipig tissue and fluids following whole-body gb vapor exposure (PDF) (Report). United States Army. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 2, 2016.

- Degenhardt; et al. (July 2004). "Improvements of the Fluoride Reactivation Method for the Verification of Nerve Agent Exposure". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. Oxfordshire, England: Oxford University Press. 28 (5): 364–371. doi:10.1093/jat/28.5.364. PMID 15239857.

- "Sarin gas as chemical agent – ThinkQuest- Library". Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- Inns, RH; NJ Tuckwell; JE Bright; TC Marrs (July 1990). "Histochemical Demonstration of Calcium Accumulation in Muscle Fibres after Experimental Organophosphate Poisoning". Hum Exp Toxicol. 9 (4): 245–250. doi:10.1177/096032719000900407. PMID 2390321. S2CID 20713579.

- Lukey, Brian J.; Romano, James A. Jr.; Salem, Harry (April 11, 2019). Chemical Warfare Agents: Biomedical and Psychological Effects, Medical Countermeasures, and Emergency Response. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-429-63296-9.

- Toxicology, National Research Council (US) Committee on (1997). Review of Acute Human-Toxicity Estimates for GB (Sarin). National Academies Press (US).

- Bide, R. W.; Armour, S. J.; Yee, E. (2005). "GB toxicity reassessed using newer techniques for estimation of human toxicity from animal inhalation toxicity data: new method for estimating acute human toxicity (GB)". Journal of Applied Toxicology. 25 (5): 393–409. doi:10.1002/jat.1074. ISSN 0260-437X. PMID 16092087. S2CID 8769521.

- Lukey, Brian J.; Romano, James A. Jr.; Salem, Harry (April 11, 2019). Chemical Warfare Agents: Biomedical and Psychological Effects, Medical Countermeasures, and Emergency Response. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-429-63296-9.

- US Army Field Manual 3-11.9 Potential Military Chemical/Biological Agents and Compounds. United States Department of Defense. 2005.

- US Army Field Manual 3-9 Potential Military Chemical/Biological Agents and Compounds. United States Department of Defense. 1990. p. 71.

- Corbridge, D. E. C. (1995). Phosphorus: An Outline of its Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Technology. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-89307-5.

- Kovarik, Zrinka; Radić, Zoran; Berman, Harvey A.; Simeon-Rudolf, Vera; Reiner, Elsa; Taylor, Palmer (March 2003). "Acetylcholinesterase active centre and gorge conformations analysed by combinatorial mutations and enantiomeric phosphonates". Biochemical Journal. London, England: Portland Press. 373 (Pt. 1): 33–40. doi:10.1042/BJ20021862. PMC 1223469. PMID 12665427.

- Benschop, H. P.; De Jong, L. P. A. (1988). "Nerve agent stereoisomers: analysis, isolation and toxicology". Accounts of Chemical Research. Washington DC: American Chemical Society. 21 (10): 368–374. doi:10.1021/ar00154a003.

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology (February 1998). "Chemical Weapons Technology" (PDF). The Militarily Critical Technologies List Part II: Weapons of Mass Destruction Technologies (ADA 330102). U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved September 4, 2020 – via Federation of American Scientists.

- Kirby, Reid (January 2006). "Nerve Gas: America's Fifteen Year Struggle for Modern Chemical weapons" (PDF). Army Chemical Review. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 11, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- The Determination of Free Base in Stabilised GB (PDF). United Kingdom: UK Ministry of Supply. 1956. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2014.

- Tu, Anthony. "New Information Revealed By Aum Shinrikyo Death Row Inmate Dr. Tomomasa Nakagawa" (PDF).

- Seto, Yasuo (June 2001). "The Sarin Gas Attack in Japan and the Related Forensic Investigation". OPCW.

- Chemical agent and munition disposal summary of the U.S. army's experience (PDF). United States Army. 1987. pp. B-30. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 19, 2015.

- Hedges, Michael (May 18, 2004). "Shell said to contain sarin poses questions for U.S." Houston Chronicle. p. A1. Archived from the original on October 12, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- cit-OPDC. The preparatory manual to chemical warfare. Vol 1: Sarin.

- "Toxic Substances Portal – Diisopropyl Methylphosphonate (DIMP)". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

- "Nerve agents". OPCW.

- Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2000). Inorganic Chemistry (1st ed.). New York: Prentice Hall. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-582-31080-3.

- Ian Sample, The Guardian, September 17, 2013, Sarin: the deadly history of the nerve agent used in Syria

- "Stability of Iraq's Chemical Weapon Stockpile". United States Central Intelligence Agency. July 15, 1996. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- Russell Goldmanpril (April 6, 2017). "Key Points on Sarin: The 'Most Volatile' of Nerve Agents". New York Times.

- Richard J. Evans (2008). The Third Reich at War, 1939–1945. Penguin. p. 669. ISBN 978-1-59420-206-3. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- "A Short History of the Development of Nerve Gases". Noblis. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011.

- Georg, Friedrich (2003). Hitler's Miracle Weapons: The Secret History Of The Rockets And Flying Crafts Of The Third Reich; from the V-1 to the A-9: Unconventional Short- and Medium-Range Weapons. Helion. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-87-462262-8.

- "Nerve gas death was 'unlawful'". BBC News Online. November 15, 2004.

- Blixen, Samuel (January 13, 1999). "Pinochet's Mad Scientist". Consortium News.

- "Towley reveló uso de gas sarín antes de ser expulsado de Chile". El Mercurio (in Spanish). September 19, 2006.

- "Plot to kill Letelier said to involve nerve gas". New York Times. December 13, 1981. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- "1988: Thousands die in Halabja gas attack". BBC News. March 16, 1988. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- "Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction". Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (November 30, 2016). "Annex 3". Report of the OPCW on the Implementation of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction in 2015 (Report). p. 42. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Amy E. Smithson and Leslie-Anne Levy (October 2000). "Chapter 3 – Rethinking the Lessons of Tokyo". Ataxia: The Chemical and Biological Terrorism Threat and the US Response (Report). Henry L. Stimson Centre. pp. 91, 95, 100. Report No. 35. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- Martin, Alex (March 19, 2018). "1995 Aum sarin attack on Tokyo subway still haunts, leaving questions unanswered". The Japan Times Online.

- "More of Kremlin's Opponents Are Ending Up Dead". The New York Times. August 21, 2016.

- Ian R Kenyon (June 2002). "The chemical weapons convention and OPCW: the challenges of the 21st century" (PDF). The CBW Conventions Bulletin. Harvard Sussex Program on CBW Armament and Arms Limitation (56): 47.

- Brunker, Mike (May 17, 2004). "Bomb said to hold deadly Sarin gas explodes in Iraq". MSNBC. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- Barnard, Anne (March 19, 2013). "Syria and Activists Trade Charges on Chemical Weapons". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- Murphy, Joe (September 5, 2013). "Cameron: British scientists have proof deadly Sarin gas was used in chemical weapons attack". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on September 6, 2013.

- "Syria: Thousands suffering neurotoxic symptoms treated in hospitals supported by MSF". Médecins Sans Frontières. August 24, 2013. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- "NGO says 322 died in Syria 'toxic gas' attacks". AFP. August 25, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- "Bodies still being found after alleged Syria chemical attack: opposition". Dailystar.com.lb. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- "Chemical attack of 4 April 2017 (Khan Sheikhoun): Clandestine Syrian chemical weapons programme" (PDF). Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Chulov, Martin (September 6, 2017). "Syrian regime dropped sarin on rebel-held town in April, UN confirms". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- OPCW Issues Fact-Finding Mission Reports on Chemical Weapons Use Allegations in Douma, Syria in 2018 and in Al-Hamadaniya and Karm Al-Tarrab in 2016 (Report). Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. July 6, 2018. Retrieved July 14, 2018.