Eurypterida

Euryptérides, Scorpions de mer, gigantostracés

| Règne | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Embranchement | Arthropoda |

| Sous-embr. | Chelicerata |

| Clade | Dekatriata |

Les euryptérides (Eurypterida), ou gigantostracés, forment un ordre éteint d'arthropodes chélicérates marins jusqu'au Carbonifère ou ils deviennent – dans une petite majorité – terrestres comme Megarachne, une araignée grosse comme une tête humaine. Couramment appelés scorpions de mer, ils ne comptent que des formes fossiles (de l'Ordovicien moyen au Permien) dont certaines atteignent plus de 2 mètres de long. Ils étaient situés tout en haut de la chaîne alimentaire de l'ère Paléozoïque.

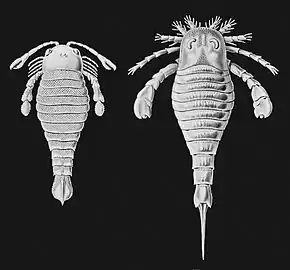

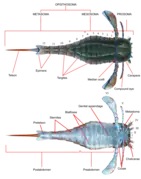

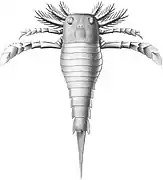

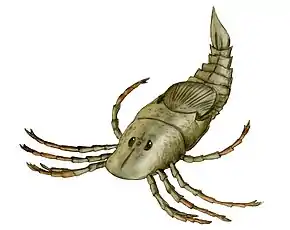

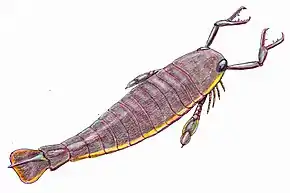

Description et caractéristiques

Leur allure était proche de celle des scorpions actuels : un corps allongé et prolongé par une longue queue articulée, et un thorax équipé de pinces redoutables, avec une tête munie de plusieurs paires d'yeux. Une paire de pattes était modifiée en nageoires, terminées par de larges palettes natatoires (sauf chez les espèces purement benthiques). Ils étaient sans doute des prédateurs efficaces, même si certaines espèces devaient être plutôt charognardes ou opportunistes (comme les actuelles limules). La plupart des espèces présentent un aiguillon effilé au bout de leur queue : comme les scorpions modernes, ils injectaient peut-être du venin à leurs proies.

Les euryptérides disputent au genre Arthropleura (un myriapode qui mesure jusqu'à 2 m de long)[1], le titre de plus grand arthropode ayant existé sur Terre. D'une manière générale, les arthropodes sont limités en taille par leur système de respiration. Malgré cela, quelques grands arthropodes comme les euryptérides ont pu se développer grâce à un air et donc à une eau qui étaient plus riches en oxygène (jusqu'à 35 %) qu'aujourd'hui (21 %)[2],[3].

Anatomie d'un euryptéride

Anatomie d'un euryptéride Exemple de fossile bien conservé

Exemple de fossile bien conservé Reconstitution d'artiste

Reconstitution d'artiste Modèle 3D

Modèle 3D

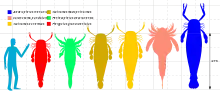

Taille

La taille des euryptères était très variable et dépendait de facteurs tels que le mode de vie, l'environnement et les affinités taxonomiques. Des tailles d'environ 100 centimètres sont courantes dans la plupart des groupes d'euryptères[4]. Le plus petit euryptère, Alkenopterus burglahrensis, ne mesurait que 2,03 centimètres de long[5].

Le plus grand eurypteride, et le plus grand arthropode connu ayant jamais vécu, est Jaekelopterus rhenaniae. Deux autres euryptères pourraient également avoir atteint une longueur de 2,5 mètres : Erettopterus grandis (étroitement apparenté à Jaekelopterus) et Hibbertopterus wittebergensis, mais E. grandis est très fragmentaire et l'estimation de la taille de H. wittenbergensis est basée sur des preuves de trajectoire, et non sur des restes fossiles[6].

La famille des Jaekelopterus, les Pterygotidae, est connue pour plusieurs espèces exceptionnellement grandes. Acutiramus, dont le plus grand membre, A. bohemicus, mesurait 2,1 mètres, et Pterygotus, dont la plus grande espèce, P. grandidentatus, mesurait 1,75 mètre, étaient tous deux gigantesques[7]. Plusieurs facteurs différents ont été suggérés pour expliquer la grande taille des ptérygotides, notamment la séduction, la prédation et la compétition pour les ressources environnementales[8].

Les euryptères géants ne se limitaient pas à la famille des Pterygotidae. Un métasome fossile isolé de 12,7 centimètres de long de l'euryptère carcinosomatoïde Carcinosoma punctatum indique que l'animal aurait atteint une longueur de 2,2 mètres, rivalisant en taille avec les ptérygotides[9]. Un autre géant était Pentecopterus decorahensis, un carcinosomatoïde primitif, qui aurait atteint une longueur de 1,7 mètre[10].

Les euryptères de grande taille sont généralement de constitution légère. Des facteurs tels que la locomotion, les coûts énergétiques de la mue et de la respiration, ainsi que les propriétés physiques réelles de l'exosquelette, limitent la taille que les arthropodes peuvent atteindre. Une construction légère réduit considérablement l'influence de ces facteurs. Les ptérygotides étaient particulièrement légers, la plupart des grands segments corporels fossilisés étant conservés étaient minces et non minéralisés. Des adaptations permettant d’alléger les exosquelettes sont également présentes dans d'autres arthropodes géants du Paléozoïque, comme l'Arthropleura, un mille-pattes géant, et sont peut-être vitales pour l'évolution de la taille géante chez les arthropodes[7],[11].

Registre fossile

L'espèce connue la plus ancienne d'euryptéride est Pentecopterus decorahensis découverte en 2015, et datant du début du Darriwilien (Ordovicien moyen). Cette espèce étant déjà relativement complexe, cette découverte suggère que les premiers euryptérides seraient apparus au moins au tout début de l'Ordovicien, il y a environ 485 millions d'années[1].

Les euryptérides connurent un grand succès évolutif au Silurien et au Dévonien où ils étaient parmi les principaux super-prédateurs, mais seuls deux groupes survécurent à la fin du Dévonien (les Adelophtalmoidea et les Stylonurina), qui disparurent à leur tour au Permien. Leur existence fut donc bornée entre environ -500 et -252 millions d'années avant nos jours[1].

Classification

Liste des genres selon Paleobiology Database (septembre 2016)[12] et Eurypterids.co.uk pour la classification[13]:

Sous-ordre Stylonurina Diener, 1924:

- Super-famille Rhenopteroidea Størmer, 1951

- Famille Rhenopteridae Størmer, 1951

- Alkenopterus Størmer, 1974

- Brachyopterella Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Brachyopterus Størmer, 1951

- Kiaeropterus Waterston, 1979

- Leiopterella Lamsdell, Braddy, Loeffler, & Dineley, 2010

- Rhenopterus Størmer, 1936

- Famille Rhenopteridae Størmer, 1951

- Super-famille Stylonuroidea Kjellesvig-Waering, 1959

- Famille Parastylonuridae Waterston, 1979

- Parastylonurus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Stylonurella Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Famille Stylonuridae Diener, 1924

- Ctenopterus Clarke & Ruedemann, 1912

- Laurieipterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Pagea Waterston, 1962

- Stylonurus Page, 1856

- Famille Parastylonuridae Waterston, 1979

- Super-famille Kokomopteroidea Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Famille Kokomopteridae Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Kokomopterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Lamontopterus Waterston, 1979

- Famille Hardieopteridae Tollerton, 1989

- Hallipterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1963

- Tarsopterella Størmer, 1951

- Famille Kokomopteridae Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Super-famille Hibbertopteroidea Kjellesvig-Waering, 1959

- Famille Drepanopteridae Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Drepanopterus Laurie, 1892

- Famille Hibbertopteridae Kjellesvig-Waering, 1959

- Campylocephalus Eichwald, 1860

- Cyrtoctenus Størmer & Waterston, 1968

- Dunsopterus Waterston, 1968

- Hastimima White, 1908

- Hibbertopterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1959

- Vernonopterus Waterston, 1957

- Famille Mycteroptidae Cope, 1886

- Megarachne Hünicken, 1980

- Mycterops Cope, 1886

- Woodwardopterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1959

- Famille Drepanopteridae Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Incertae sedis

- Stylonuroides Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

Sous-ordre Eurypterina Burmeister, 1843:

- Super-famille Moselopteroidea Lamsdell, Braddy, & Tetlie, 2010

- Famille Moselopteridae Lamsdell, Braddy, & Tetlie, 2010

- Moselopterus Størmer, 1974

- Vinetopterus Poschmann & Tetlie, 2004

- Famille Moselopteridae Lamsdell, Braddy, & Tetlie, 2010

- Super-famille Onychopterelloidea Lamsdell, 2011

- Famille Onychopterellidae Lamsdell 2011

- Onychopterella Størmer, 1951

- Tylopterella Størmer, 1951

- Famille Onychopterellidae Lamsdell 2011

- Super-famille Megalograptoidea Caster & Kjellesvig-Waering, 1955

- Famille Megalograptidae Caster & Kjellesvig-Waering, 1955

- Echinognathus Walcott, 1882

- Megalograptus Miller, 1874

- Pentecopterus Lamsdell, James C et al., 2015

- Famille Megalograptidae Caster & Kjellesvig-Waering, 1955

- Super-famille Eurypteroidea Burmeister, 1843

- Famille Dolichopteridae Kjellesvig-Waering & Størmer, 1952

- Dolichopterus Hall, 1859

- Ruedemannipterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Buffalopterus Kjellesvig-Waering & Heubusch, 1962

- Strobilopterus Ruedemann, 1935

- Syntomopterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1961

- Famille Eurypteridae Burmeister, 1843

- Eurypterus De Kay, 1825

- Famille Erieopteridae Tollerton, 1989

- Erieopterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1958

- Famille Dolichopteridae Kjellesvig-Waering & Størmer, 1952

- Super-famille Mixopteroidea Caster & Kjellesvig-Waering, 1955

- Famille Carcinosomatidae Størmer, 1934

- Carcinosoma Claypole, 1890

- Eocarcinosoma Caster & Kjellesvig-Waering, 1964

- Paracarcinosoma Caster & Kjellesvig-Waering, 1964

- Rhinocarcinosoma Novojilov, 1962

- Famille Mixopteridae Caster & Kjellesvig-Waering, 1955

- Lanarkopterus Ritchie, 1968

- Mixopterus Ruedemann, 1921

- Famille Carcinosomatidae Størmer, 1934

- Super-famille Waeringopteroidea Tetlie, 2004

- Famille Orcanopteridae Tetlie, 2004

- Orcanopterus Stott, Tetlie, Braddy, Nowlan, Glasser, & Devereux, 2005

- Famille Waeringopteridae Tetlie, 2004

- Grossopterus Størmer, 1934

- Waeringopterus Leutze, 1961

- Famille Orcanopteridae Tetlie, 2004

- Super-famille Adelophthalmoidea Tollerton, 1989

- Famille Adelophthalmidae Tollerton, 1989

- Adelophthalmus Jordan in Jordan & von Mayer, 1854

- Bassipterus Kjellesvig-Waering & Leutze, 1966

- Eysyslopterus Tetlie & Poschmann, 2008

- Nanahughmilleria Kjellesvig-Waering, 1961

- Parahughmilleria Kjellesvig-Waering, 1961

- Pittsfordipterus Kjellesvig-Waering & Leutze, 1966

- Famille Adelophthalmidae Tollerton, 1989

- Super-famille Pterygotioidea Clarke & Ruedemann, 1912

- Famille Hughmilleriidae Kjellesvig-Waering, 1951

- Herefordopterus Tetlie, 2006

- Hughmilleria Sarle, 1902

- Famille Slimoniidae Novojilov, 1968

- Slimonia Page, 1856

- Salteropterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1951

- Famille Pterygotidae Clarke & Ruedemann, 1912

- Pterygotus Agassiz, 1839

- Acutiramus Ruedemann, 1935

- Ciurcopterus Tetlie & Briggs, 2009

- Erettopterus Salter in Huxley & Salter, 1859

- Jaekelopterus Waterston, 1964

- Famille Hughmilleriidae Kjellesvig-Waering, 1951

- Incertae sedis

- Clarkiepterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1966

- Dorfopterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1955

- Holmipterus Kjellesvig-Waering, 1979

- Marsupipterus Caster & Kjellesvig-Waering, 1955

- Unionopterus Chernyshev, 1948

Dolichopterus macrochirus

Dolichopterus macrochirus.png.webp) Eurypterus sp. (vue dorsale et ventrale)

Eurypterus sp. (vue dorsale et ventrale)

Mixopterus kiaeri

Mixopterus kiaeri

_(14596592278).jpg.webp) Stylonurus excelsior

Stylonurus excelsior

Phylogénie

Place au sein des chélicérates

Phylogénie des grands groupes de chélicérés, d'après Lamsdell, 2013[14] :

| Chelicerata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Voir aussi

Articles connexes

Références taxinomiques

- (en) Référence Paleobiology Database : Eurypterida Burmeister 1843 (éteint)

- (en) Référence Tree of Life Web Project : Eurypterida

- (en) Référence Arthropoda Species Files : Eurypterida (éteint)

Notes et références

- (en) Dave Marshall, « Eurypterids », sur Palaeocast.com,

- (en) Josh Clark, « Is an ancient sea scorpion the largest bug ever to live on Earth? », sur howstuffworks.com, (consulté le )

- (en) Cherry Lewis, « Giant fossil sea scorpion », sur bris.ac.uk, (consulté le )

- Tetlie 2007, p. 557.

- Poschmann et Tetlie 2004, p. 189.

- Lamsdell et Braddy 2009, Supplementary information.

- Braddy, Poschmann et Tetlie 2008, p. 107.

- Briggs 1985, p. 157–158.

- Kjellesvig-Waering 1961, p. 830.

- Lamsdell et al. 2015, p. 15.

- Kraus et Brauckmann 2003, p. 5–50.

- Fossilworks Paleobiology Database, consulté le septembre 2016

- http://eurypterids.co.uk/encyclopedia.htm

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259572939_Revised_systematics_of_Palaeozoic_%27horseshoe_crabs%27_and_the_myth_of_monophyletic_Xiphosura

Bibliographie

- Carl T. Bergstrom et Lee Alan Dugatkin, Evolution, Norton, (ISBN 978-0393913415, lire en ligne)

- Simon J. Braddy et Jason A. Dunlop, « The functional morphology of mating in the Silurian eurypterid, Baltoeurypterus tetragonophthalmus (Fischer, 1839) », Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 120, no 4, , p. 435–461 (ISSN 0024-4082, DOI 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1997.tb01282.x)

- Simon J. Braddy et John E. Almond, « Eurypterid trackways from the Table Mountain Group (Ordovician) of South Africa », Journal of African Earth Sciences, vol. 29, no 1, , p. 165–177 (DOI 10.1016/S0899-5362(99)00087-1, Bibcode 1999JAfES..29..165B)

- Simon J. Braddy, Markus Poschmann et O. Erik Tetlie, « Giant claw reveals the largest ever arthropod », Biology Letters, vol. 4, no 1, , p. 106–109 (PMID 18029297, PMCID 2412931, DOI 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0491)

- David K. Brezinski et Albert D. Kollar, « Reevaluation of the Age and Provenance of the Giant Palmichnium kosinskiorum Eurypterid Trackway, from Elk County, Pennsylvania », Annals of Carnegie Museum, vol. 84, no 1, , p. 39–45 (DOI 10.2992/007.084.0105)

- Derek E. G. Briggs, « Gigantism in Palaeozoic arthropods », Special Papers in Palaeontology, vol. 33, , p. 157–158 (lire en ligne)

- Hermann Burmeister, Die Organisation der Trilobiten aus ihren lebenden Verwandten entwickelt, Georg Reimer, (lire en ligne)

- John Mason Clarke et Rudolf Ruedemann, The Eurypterida of New York, University of California Libraries, (ISBN 978-1125460221, lire en ligne)

- Jason A. Dunlop, David Penney et Denise Jekel, World Spider Catalog, Natural History Museum Bern, , « A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives »

- Anthony Hallam et Paul B. Wignall, Mass Extinctions and Their Aftermath, Oxford University Press, (ISBN 978-0198549161, lire en ligne)

- Nils-Martin Hanken et Leif Størmer, « The trail of a large Silurian eurypterid », Fossils and Strata, vol. 4, , p. 255–270 (lire en ligne)

- Daniel I. Hembree, Brian F. Platt et Jon J. Smith, Experimental Approaches to Understanding Fossil Organisms: Lessons from the Living, Springer Science & Business, (ISBN 978-9401787208, lire en ligne)

- John Henderson, « IV. Notice of Slimonia Acuminata, from the Silurian of the Pentland Hills », Transactions of the Edinburgh Geological Society, vol. 1, no 1, , p. 15–18 (DOI 10.1144/transed.1.1.15)

- John Sterling Kingsley, « The Classification of the Arthropoda », The American Naturalist, vol. 28, no 326, , p. 118–135 (DOI 10.1086/275878, JSTOR 2452113)

- Erik N. Kjellesvig-Waering, « The Silurian Eurypterida of the Welsh Borderland », Journal of Paleontology, vol. 35, no 4, , p. 789–835 (JSTOR 1301214)

- Erik N. Kjellesvig-Waering, « A Synopsis of the Family Pterygotidae Clarke and Ruedemann, 1912 (Eurypterida) », Journal of Paleontology, vol. 38, no 2, , p. 331–361 (JSTOR 1301554)

- Otto Kraus et Carsten Brauckmann, « Fossil giants and surviving dwarfs. Arthropleurida and Pselaphognatha (Atelocerata, Diplopoda): characters, phylogenetic relationships and construction », Verhandlungen des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins in Hamburg, vol. 40, , p. 5–50 (lire en ligne)

- Barry S. Kues et Kenneth K. Kietzke, « A Large Assemblage of a New Eurypterid from the Red Tanks Member, Madera Formation (Late Pennsylvanian-Early Permian) of New Mexico », Journal of Paleontology, vol. 55, no 4, , p. 709–729 (JSTOR 1304420)

- James C. Lamsdell et Simon J. Braddy, « Cope's Rule and Romer's theory: patterns of diversity and gigantism in eurypterids and Palaeozoic vertebrates », Biology Letters, vol. 6, no 2, , p. 265–269 (PMID 19828493, PMCID 2865068, DOI 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0700)

- James C. Lamsdell, Simon J. Braddy et O. Erik Tetlie, « Redescription of Drepanopterus abonensis (Chelicerata: Eurypterida: Stylonurina) from the late Devonian of Portishead, UK », Palaeontology, vol. 52, no 5, , p. 1113–1139 (ISSN 1475-4983, DOI 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00902.x)

- James C. Lamsdell, Simon J. Braddy et O. Erik Tetlie, « The systematics and phylogeny of the Stylonurina (Arthropoda: Chelicerata: Eurypterida) », Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, vol. 8, no 1, , p. 49–61 (ISSN 1478-0941, DOI 10.1080/14772011003603564)

- James C. Lamsdell, « Revised systematics of Palaeozoic 'horseshoe crabs' and the myth of monophyletic Xiphosura », Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 167, , p. 1–27 (DOI 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00874.x)

- James C. Lamsdell et Paul Selden, « Babes in the wood – a unique window into sea scorpion ontogeny », BMC Evolutionary Biology, vol. 13, no 98, , p. 98 (PMID 23663507, PMCID 3679797, DOI 10.1186/1471-2148-13-98)

- James C. Lamsdell, Selectivity in the evolution of Palaeozoic arthropod groups, with focus on mass extinctions and radiations: a phylogenetic approach, University of Kansas, (lire en ligne)

- James C. Lamsdell, Derek E. G. Briggs, Huaibao Liu, Brian J. Witzke et Robert M. McKay, « The oldest described eurypterid: a giant Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) megalograptid from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa », BMC Evolutionary Biology, vol. 15, no 169, , p. 169 (PMID 26324341, PMCID 4556007, DOI 10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9)

- E. Ray Lankester, « Professor Claus and the classification of the Arthropoda », Annals and Magazine of Natural History, vol. 17, no 100, , p. 364–372 (DOI 10.1080/00222938609460154, lire en ligne)

- Frederick M'Coy, « XLI.—On the classification of some British fossil Crustacea, with notices of new forms in the University Collection at Cambridge », Annals and Magazine of Natural History, vol. 4, no 24, , p. 392–414 (DOI 10.1080/03745486009494858, lire en ligne)

- Victoria E. McCoy, James C. Lamsdell, Markus Poschmann, Ross P. Anderson et Derek E. G. Briggs, « All the better to see you with: eyes and claws reveal the evolution of divergent ecological roles in giant pterygotid eurypterids », Biology Letters, vol. 11, no 8, , p. 20150564 (PMID 26289442, PMCID 4571687, DOI 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0564)

- John R. Nudds et Paul Selden, Fossil Ecosystems of North America: A Guide to the Sites and their Extraordinary Biotas, Manson Publishing, (ISBN 978-1-84076-088-0, lire en ligne)

- Marjorie O'Connell, « The Habitat of the Eurypterida », The Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences, vol. 11, no 3, , p. 1–278 (lire en ligne)

- Javier Ortega‐Hernández, David A. Legg et Simon J. Braddy, « The phylogeny of aglaspidid arthropods and the internal relationships within Artiopoda », Cladistics, vol. 29, , p. 15–45 (ISSN 1502-3931, DOI 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00413.x)

- Roy E. Plotnick et Tomasz K. Baumiller, « The pterygotid telson as a biological rudder », Lethaia, vol. 21, no 1, , p. 13–27 (ISSN 1502-3931, DOI 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1988.tb01746.x)

- Markus Poschmann et O. Erik Tetlie, « On the Emsian (Early Devonian) arthropods of the Rhenish Slate Mountains: 4. The eurypterids Alkenopterus and Vinetopterus n. gen. (Arthropoda: Chelicerata) », Senckenbergiana Lethaea, vol. 84, nos 1–2, , p. 173–193 (DOI 10.1007/BF03043470)

- Paul Selden, « Eurypterid respiration », Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 309, no 1138, , p. 219–226 (DOI 10.1098/rstb.1985.0081, Bibcode 1985RSPTB.309..219S, lire en ligne)

- Paul Selden, « Autecology of Silurian Eurypterids », Special Papers in Palaeontology, vol. 32, , p. 39–54 (ISSN 0038-6804, lire en ligne [archive du ])

- Leif Størmer, Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part P Arthropoda 2, Chelicerata, University of Kansas Press, (ASIN B0043KRIVC), « Merostomata »

- O. Erik Tetlie, « Two new Silurian species of Eurypterus (Chelicerata: Eurypterida) from Norway and Canada and the phylogeny of the genus », Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, vol. 4, no 4, , p. 397–412 (ISSN 1478-0941, DOI 10.1017/S1477201906001921, lire en ligne)

- O. Erik Tetlie et Peter Van Roy, « A reappraisal of Eurypterus dumonti Stainier, 1917 and its position within the Adelophthalmidae Tollerton, 1989 », Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, vol. 76, , p. 79–90 (lire en ligne)

- O. Erik Tetlie, « Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata) », Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, vol. 252, nos 3–4, , p. 557–574 (ISSN 0031-0182, DOI 10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.011)

- O. Erik Tetlie et Michael B. Cuggy, « Phylogeny of the basal swimming eurypterids (Chelicerata; Eurypterida; Eurypterina) », Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, vol. 5, no 3, , p. 345–356 (DOI 10.1017/S1477201907002131)

- O. Erik Tetlie et Isabel Rábano, « Specimens of Eurypterus (Chelicerata, Eurypterida) in the collections of Museo Geominero (Geological Survey of Spain), Madrid », Boletín Geológico y Minero, vol. 118, no 1, , p. 117–126 (ISSN 0366-0176, lire en ligne [archive du ])

- O. Erik Tetlie, « Hallipterus excelsior, a Stylonurid (Chelicerata: Eurypterida) from the Late Devonian Catskill Delta Complex, and Its Phylogenetic Position in the Hardieopteridae », Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, vol. 49, no 1, , p. 19–30 (DOI 10.3374/0079-032X(2008)49[19:HEASCE]2.0.CO;2)

- O. Erik Tetlie et Derek E. G. Briggs, « The origin of pterygotid eurypterids (Chelicerata: Eurypterida) », Palaeontology, vol. 52, no 5, , p. 1141–1148 (ISSN 0024-4082, DOI 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00907.x)

- Victor P. Tollerton, « Morphology, Taxonomy, and Classification of the Order Eurypterida Burmeister, 1843 », Journal of Paleontology, vol. 63, no 5, , p. 642–657 (DOI 10.1017/S0022336000041275, JSTOR 1305624)

- Peter Van Roy, Derek E. G. Briggs et Robert R. Gaines, « The Fezouata fossils of Morocco; an extraordinary record of marine life in the Early Ordovician », Journal of the Geological Society, vol. 172, no 5, , p. 541–549 (ISSN 0016-7649, DOI 10.1144/jgs2015-017, Bibcode 2015JGSoc.172..541V, lire en ligne)

- Matthew B. Vrazo et Samuel J. Ciurca Jr., « New trace fossil evidence for eurypterid swimming behaviour », Palaeontology, vol. 61, no 2, , p. 235–252 (DOI 10.1111/pala.12336)

- David White, « Flora of the Hermit Shale, Grand Canyon, Arizona », Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 13, no 8, , p. 574–575 (PMID 16587225, PMCID 1085121, DOI 10.1073/pnas.13.8.574)

- Martin A. Whyte, « A gigantic fossil arthropod trackway », Nature, vol. 438, no 7068, , p. 576 (PMID 16319874, DOI 10.1038/438576a)

- Henry Woodward, « On some New Species of Crustacea belonging to the Order Eurypterida », Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, vol. 21, nos 1–2, , p. 484–486 (DOI 10.1144/GSL.JGS.1865.021.01-02.52)

- Portail de la paléontologie