Ankle fracture

| Ankle fracture | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Broken ankle[1] | |

| |

| Fracture of both sides of the ankle with dislocation as seen on anteroposterior X-ray. (1) fibula, (2) tibia, (arrow) medial malleolus, (arrowhead) lateral malleolus | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Pain, swelling, bruising, inability to walk[1] |

| Complications | High ankle sprain, compartment syndrome, decreased range of motion, malunion[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Young males, older females[2] |

| Types | Lateral malleolus, medial malleolus, posterior malleolus, bimalleolar, trimalleolar[1] |

| Causes | Rolling the ankle, blunt trauma[2] |

| Diagnostic method | X-rays based on the Ottawa ankle rule[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Rheumatoid arthritis, gout, septic arthritis, Achilles tendon rupture[2] |

| Treatment | Splinting, casting, surgery[1] |

| Frequency | ~1 per 1000/year[2] |

An ankle fracture is a break of one or more ankle bones.[1] Symptoms may include pain, swelling, bruising, and an inability to walk on the leg.[1] Complications may include an associated high ankle sprain, compartment syndrome, decreased range of motion, and malunion.[1][2]

The cause may include excessive stress on the joint such as from rolling an ankle or blunt trauma.[2][1] Types include lateral malleolus, medial malleolus, posterior malleolus, bimalleolar, and trimalleolar fractures.[1] The need for X-rays may be determined by the Ottawa ankle rule.[2]

Treatment is with splinting, casting, or surgery.[1] Ruling out other injuries may also be required.[2] Significant recovery generally occurs within four months; however, completely recovery may take up to two years.[1] They occur in about 1.7 per 1000 adults and 1 per 1000 children per year.[3][2] They occur most commonly in young males and older females.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of an ankle fracture can be similar to those of ankle sprains (pain), though typically they are often more severe by comparison. It is exceedingly rare for the ankle joint to dislocate in the presence of ligamentous injury alone. However, in the setting of an ankle fracture the talus can become unstable and subluxate or dislocate[4]. Patients may notice ecchymosis ("black and blue" coloraction from bleeding under the skin), or there may be an abnormal position, alignment, gross instability, or lack of normal motion secondary to pain[1]

In a displaced fracture the skin is sometimes tented over a sharp edge of broken bone. The sharp fragments of broken bone sometimes tear the skin and form a laceration that communicates with the broken bone or joint space. This is known as an 'open' fracture and has a high incidence of infection if not promptly treated. Nearly all displaced ankle fractures are now treated surgically to insure proper alignment of the displaced fragments.[5]

Cause

An ankle fracture can be due to blunt force or a high degree of stress on said area.[2]

Anatomy

The ankle region refers to where the leg meets the foot (talocrural region).[6] The ankle joint is a highly constrained, complex hinge joint composed of three bones: the tibia, the fibula, and the talus.[7][8] The weight-bearing aspect of the tibia closest to the foot (known as the plafond) connects with the talus. This articulation (where two bones meet) is primarily responsible for plantarflexion (moving your foot down) and dorsiflexion (moving your foot up).[8] Together the tibia and fibula form a bracket-shaped socket known as the mortise, into which the dome-shaped talus fits.[9] The talus and the fibula are connected by a strong group of ligaments, which provide support for the lateral aspect of the ankle. These ligaments include the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) and the posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL).[10] The calcaneofibular ligament (CFL), which connects the fibula to the calcaneus, or heel bone, also provides lateral support. The deltoid ligament provides support to the medial part of the ankle (closest to the midline). It prevents the foot from excessively everting, or turning outwards while also preventing the talus from externally rotating.[10] The distal parts of the tibia and fibula are connected by a connective tissue network referred to as the syndesmosis, which consists of four ligaments and the interosseous membrane.[10]

Diagnosis

On clinical examination, it is important to evaluate the exact location of the pain, the range of motion and the condition of the nerves[11]. It is important to palpate the calf bone (fibula) because there may be an associated fracture proximally (Maisonneuve fracture)[12], and to palpate the sole of the foot to look for a Jones fracture at the base of fifth metatarsal [13]Evaluation of ankle injuries for fracture is done with the Ottawa ankle rules, a set of rules that were developed to minimize unnecessary X-rays.[14] There are three x-ray views in a complete ankle series: anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique [15]. The mortise view an anteroposterior x-ray taken with the ankle internally rotated until the lateral malleolus is on the same horizontal plane as the medial malleolus, resulting in a position where there normally is no superimposition of tibia and fibula on each other.[16]

X-ray

On X-rays, there can be a fracture of the medial malleolus, the lateral malleolus, or of the anterior/posterior margin of the distal tibia. [17] If both the lateral and medial malleoli are broken, this is called a bimalleolar fracture[18]. If the posterior malleolus is also fractured, this is called a trimalleolar fracture. [19]

A triplane fracture of the ankle as seen on plain X-ray

A triplane fracture of the ankle as seen on plain X-ray A triplane fracture of the ankle as seen on CT

A triplane fracture of the ankle as seen on CT A triplane fracture of the ankle as seen on CT

A triplane fracture of the ankle as seen on CT

Fracture types

- Pilon fracture (Plafond fracture), a fracture of the distal part of the tibia, involving its articular surface at the ankle joint.[20]

- Wagstaffe-Le Fort avulsion fracture¨, a vertical fracture of the antero-medial part of the distal fibula with avulsion of the anterior tibiofibular ligament.[21]

- Tillaux fracture, a Salter–Harris type III fracture through the anterolateral aspect of the distal tibial epiphysis.[22]

Classification

There are several classification schemes for ankle fractures:

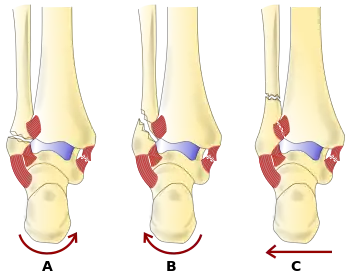

- The Lauge-Hansen classification categorises fractures based on the mechanism of the injury as it relates to the position of the foot and the deforming force [23]

- The Danis-Weber classification categorises ankle fractures by the level of the fracture of the distal fibula (type A = below the syndesmotic ligament, type B = at its level, type C = above the ligament), with use in assessing injury to the syndesmosis and the interosseous membrane[24]

- The Herscovici classification categorises medial malleolus fractures of the distal tibia based on level.[25]

- The Ruedi-Allgower classification categorizes pilon fractures of the distal tibia.[26]

Treatment

Treatment of ankle fractures is dictated by the stability of the ankle joint. Certain fractures patterns are deemed stable, and may be treated similar to ankle sprains. All other types require surgery, which is usually performed with permanently implanted metal hardware that holds the bones in place while the natural healing process occurs. A cast or splint will be required to immobilize the ankle following surgery.[1]

In children recovery may be faster with an ankle brace rather than a full cast in those with otherwise stable fractures.[3]

Epidemiology

In children ankle fractures occur in about 1 per 1000 per year.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Ankle Fractures (Broken Ankle) - OrthoInfo - AAOS". www.orthoinfo.org. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Wire, Jessica (9 May 2019). "Ankle Fractures". StatPearls. PMID 31194464.

- 1 2 3 Yeung, DE; Jia, X; Miller, CA; Barker, SL (1 April 2016). "Interventions for treating ankle fractures in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD010836. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010836.pub2. PMC 7111433. PMID 27033333.

- ↑ Cleary, Michelle; Flanagan, Katie Walsh. Acute and Emergency Care in Athletic Training. Human Kinetics. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4925-3653-6. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ↑ "Infections After Fracture - Causes and Treatment - OrthoInfo - AAOS". www.orthoinfo.org. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Moore KL. Clinically oriented anatomy. ISBN 978-1-9751-5086-0. OCLC 1112382966.

- ↑ Brockett CL, Chapman GJ (June 2016). "Biomechanics of the ankle". Orthopaedics and Trauma. 30 (3): 232–238. doi:10.1016/j.mporth.2016.04.015. PMC 4994968. PMID 27594929.

- 1 2 Thompson CJ (2015). Netter's concise orthopaedic anatomy, updated edition. Elsevier. ISBN 0-323-42970-X. OCLC 946457800.

- ↑ "The Ankle Joint - Articulations - Movements - TeachMeAnatomy". Archived from the original on 2021-02-02. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- 1 2 3 Coughlin MJ, Saltzman CL, Mann RA (2014). Mann's surgery of the foot and ankle. Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-07242-7. OCLC 883562707.

- ↑ Alazzawi, Sulaiman; Sukeik, Mohamed; King, Daniel; Vemulapalli, Krishna (18 January 2017). "Foot and ankle history and clinical examination: A guide to everyday practice". World Journal of Orthopedics. 8 (1): 21–29. doi:10.5312/wjo.v8.i1.21. ISSN 2218-5836. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ↑ Bennett, D. Lee; El-Khoury, Georges Y. Pearls and Pitfalls in Musculoskeletal Imaging: Variants and Other Difficult Diagnoses. Cambridge University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-107-06700-4. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ↑ Joel A. DeLisa; Bruce M. Gans; Nicholas E. Walsh (2005). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 881–. ISBN 978-0-7817-4130-9. Archived from the original on 2017-01-07.

- ↑ "What are the Ottawa Ankle Rules and how are they used to diagnose ankle sprain?". www.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ↑ MPT, James Swain; Phd, Kenneth W. Bush, MPT; PhD, Juliette Brosing. Diagnostic Imaging for Physical Therapists. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-4160-2903-8. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ↑ Frank, Ashleigh L.; Groen, Kimberly (2020). "Ankle Dislocation". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ↑ Patel, Parth; Russell, Timothy G. (2020). "Ankle Radiographic Evaluation". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ↑ Tejwani, Nirmal C.; McLaurin, Toni M.; Walsh, Michael; Bhadsavle, Siraj; Koval, Kenneth J.; Egol, Kenneth A. (July 2007). "Are outcomes of bimalleolar fractures poorer than those of lateral malleolar fractures with medial ligamentous injury?". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 89 (7): 1438–1441. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.01006. ISSN 0021-9355. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ↑ Sueki, Derrick; Brechter, Jacklyn. Orthopedic Rehabilitation Clinical Advisor - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 647. ISBN 978-0-323-07252-6. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ↑ "Pilon Fractures of the Ankle - OrthoInfo - AAOS". www.orthoinfo.org. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ↑ MIAP, Mukesh Sharma BPT MPT Musculoskeletal Disorders. Simplified Approach to Orthopedic Physiotherapy: Rationale and Rehab. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. p. 138. ISBN 978-93-5270-961-8. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ↑ "Wheeless Online". Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ Tartaglione, Jason P.; Rosenbaum, Andrew J.; Abousayed, Mostafa; DiPreta, John A. (October 2015). "Classifications in Brief: Lauge-Hansen Classification of Ankle Fractures". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 473 (10): 3323–3328. doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4306-x. ISSN 0009-921X. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ Mcrae, Ronald; Esser, Max. Practical Fracture Treatment (Fifth ed.). p. 382. ISBN 978-0-443-06876-8.

- ↑ Khodaee, Morteza; Waterbrook, Anna L.; Gammons, Matthew. Sports-related Fractures, Dislocations and Trauma: Advanced On- and Off-field Management. Springer Nature. p. 451. ISBN 978-3-030-36790-9. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ Luo, T. David; Eady, J. Matthew; Aneja, Arun; Miller, Anna N. "Classifications in Brief: Rüedi-Allgöwer Classification of Tibial Plafond Fractures". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 475 (7): 1923–1928. doi:10.1007/s11999-016-5219-z. ISSN 1528-1132. Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ankle fracture |