Bethlem myopathy

| Bethlem myopathy | |

|---|---|

| |

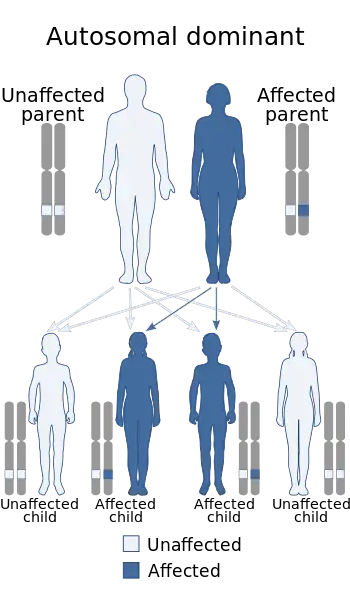

| Bethlem myopathy has an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (autosomal recessive form exists as well[1]) | |

Bethlem myopathy is an autosomal dominant myopathy, classified as a congenital form of muscular dystrophy, that is caused by a mutation in one of the three genes coding for type VI collagen.[2] These include COL6A1, COL6A2, and COL6A3.[3] Gower's sign, tiptoe-walking and contractures of the joints (especially the fingers) are typical signs and symptoms of the disease. Bethlem myopathy could be diagnosed based on clinical examinations and laboratory tests may be recommended. Currently there is no cure for the disease and symptomatic treatment is used to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life. Bethlem myopathy affects about 1 in 200,000 people.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The onset of this disease can begin even before birth but is more commonly in childhood or later into adult life. The progression is slow, with symptoms of weakness and walking difficulties sometimes not presenting until middle age. Early symptoms include Gower's sign ("climbing" up the thighs with the hands when rising from the floor) and tiptoe-walking caused by the beginning of contractures.

Contractures of the fingers are a typical symptom of Bethlem myopathy but not of the related Ullrich's myopathy (which does include contractures of arms and legs, as does Bethlem myopathy). Serum creatine kinase is elevated in Bethlem myopathy, as there is ongoing muscle cell death. Patients with Bethlem myopathy may expect a normal life span and continued mobility into adulthood.

Diagnosis

The disease could be diagnosed based on a clinical examination, which identifies signs and symptoms generally associated with the people who have the condition. Additional laboratory tests may be recommended. Creatine kinase (CK) blood test results will generally be normal or only slightly elevated. Skin biopsy, MRI of the muscles, electromyography (EMG) are the main testing methods of the disease. The diagnosis can be confirmed with genetic testing of the COL6A1, COL6A2, and COL6A3 genes.[5]

Phenotypes of overlap between Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy (UCMD) and Bethlem can be assumed. In the differential diagnosis of UCDM, even in patients without finger contractures, Bethlem myopathy could be considered.[6]

Treatment

Currently there is no cure for the disease. Symptomatic treatment, which aims to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life is the main treatment method of Bethlem myopathy. It is believed that physical therapy, stretching exercises, orthoses such as braces and splints, and mobility aids like a walker or wheelchair are beneficial to patient's condition.[5]

Surgical options could be considered in rare instances, in order to help with joint contractures or scoliosis.[5] Contractures of the legs can be alleviated with heel-cord surgery followed by bracing and regular physical therapy. Repeated surgeries to lengthen the heel cords may be needed as the child grows to adulthood.[2]

Epidemiology

According to a Japanese study from 2007 Bethlem myopathy affects about 1 in 200,000 people.[4] A 2009 study concerning the prevalence of genetic muscle disease in Northern England estimated the prevalence of Bethlem myopathy to be at 0.77:100,000.[7] Together with the UCMD it is believed to be underdiagnosed. Both conditions have been described in individuals from a variety of ethnic backgrounds.[8]

References

- ↑ RESERVED, INSERM US14 -- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Bethlem myopathy". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- 1 2 Jobsis GJ, Boers JM, Barth PG, de Visser M (1999). "Bethlem myopathy: a slowly-progressive congenital muscular dystrophy with contractures". Brain. 122 (4): 649–655. doi:10.1093/brain/122.4.649. PMID 10219778.

- ↑ Lampe AK, Bushby KM (September 2005). "Collagen VI related muscle disorders". J. Med. Genet. 42 (9): 673–85. doi:10.1136/jmg.2002.002311. PMC 1736127. PMID 16141002.

- 1 2 Okada M et al (2007) Primary collagen VI deficiency is the second most common congenital muscular dystrophy in Japan. Neurolog 69:1035–1042

- 1 2 3 "Bethlem myopathy | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-10-17. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ↑ Reed, Umbertina Conti; Ferreira, Lucio Gobbo; Liu, Enna Cristina; Resende, Maria Bernadete Dutra; Carvalho, Mary Souza; Marie, Suely Kazue; Scaff, Milberto (September 2005). "Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy and bethlem myopathy: clinical and genetic heterogeneity". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 63 (3B): 785–790. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2005000500013. ISSN 0004-282X. Archived from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2021-07-25.

- ↑ Norwood, Fiona L. M.; Harling, Chris; Chinnery, Patrick F.; Eagle, Michelle; Bushby, Kate; Straub, Volker (2009). "Prevalence of genetic muscle disease in Northern England: in-depth analysis of a muscle clinic population". Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 132 (Pt 11): 3175–3186. doi:10.1093/brain/awp236. ISSN 1460-2156. PMC 4038491. PMID 19767415. Archived from the original on 2020-10-19. Retrieved 2021-07-25.

- ↑ Lampe, Anne Katrin; Flanigan, Kevin M.; Bushby, Katharine Mary; Hicks, Debbie (1993), Adam, Margaret P.; Ardinger, Holly H.; Pagon, Roberta A.; Wallace, Stephanie E. (eds.), "Collagen Type VI-Related Disorders", GeneReviews®, Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle, PMID 20301676, archived from the original on 2020-08-13, retrieved 2020-10-19

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|