Broken toe

| Broken toe | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Bedroom fracture[1] | |

| |

| X-rays of fractures of the proximal (left) and distal (right) phalanges in the little toe. | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Pain, tenderness, bruising, swelling, displacement of the bones.[2] |

| Complications | Compromised blood circulation; malunion, long-term pain, degenerative joint disease, infection[2] |

| Usual onset | Sudden[2] |

| Causes | Stubbing or crushing[2] over-extending a toe joint, stress fracture[2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Visualisation, X-rays[2] |

| Treatment | For pain and swelling,[2] rest, icing, elevation and pain medication; wearing a stiff-soled shoe; for smaller toes, buddy wrapping (taping the toe to the nearest toe, with some absorbent padding in-between);[3] rarely, a cast or surgery[3] |

| Medication | Over-the-counter painkillers[3] |

| Prognosis | 4 to 8 weeks for full healing; pain lessens within days[3] |

| Frequency | Common,[3] 8-9% of all fractures[4] |

A broken toe is a type of bone fracture.[4] Symptoms include pain when the toe is touched near the break point, or compressed along its length.[2] There may be bruising, swelling, stiffness, or displacement of the broken bone ends from their normal position.[3]

Toes usually break because they have been stubbed or crushed by typically dropping something on the toe.[2][3] Less frequently, over-extending a toe joint can break off a portion of the bone, and stress fractures are possible,[2] especially just after a sudden increase in activity.[5] Diagnosis is based on symptoms and visualisation of the toe and can be confirmed by X-rays.[3][6]

Breaks of smaller toes are usually treated with rest, taping the toe to the nearest toe, with some absorbent padding in-between, and wearing a stiff-soled shoe.[3] For pain and swelling of all toes,[2] rest, icing, elevation and pain medication are used.[3] Pain usually decreases significantly within a week, but the toe may take 4–6 weeks to heal fully.[3] As activity is slowly increased to normal levels, the toe may be a bit sore and stiff.[3] If the bone heals crooked, it may be relocated with or without surgery.[3] Broken toes can usually be cared for at home, unless the break is in the big toe, there is an open wound, or the broken ends of the bone are displaced.[3] In high-force crushing and shearing injuries, especially those with open wounds, blood circulation (tested by capillary refill) can be impaired, which needs urgent professional treatment.[2] More serious broken toes may need to be re-aligned or put in a cast; surgery is rarely needed.[3] These cases may take longer (six to eight weeks) to heal fully.[3]

Broken toes are one of the most common types of fracture seen in doctor's offices, and make up just under 10% of fractures in some offices.[2] Studies have shown that broken pinky toes are to blame for 45% of individuals complaining of loss of balance.[2]

Definition and classification

Toe bones or phalanges of the foot. Note the big toe has no middle phalanx.

People vary; sometimes the smallest toe also has none (not shown).[2]

A broken toe is a type of fracture which may be categorised as a big toe fracture or fractures of the lesser toes.[1][7] Toe fractures may be articular (affecting the joint surfaces at the ends of the bone) or diaphyseal (between the ends).[8] They can be displaced, non-displaced, closed or open.[1]

The AO Foundation/Orthopaedic Trauma Association (AO/OTA) classification generates numeric codes for describing broken toes.[8] They run 88[meaning a fracture of the phalanges].[number-code of toe, with the big toe=1 and the little toe=5].[number-code of phalanx, counting 1-3 outwards from the foot].[number-code of location on the bone, with 1 being the inner end, 3 the outer, and 2 in-between].[8] So, for instance, 88.1.2.1 means a fracture to the big toe's innermost bone, at the proximal end.[8][9] A letter can be added to describe the fracture pattern.[9]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms include pain when the site of the fracture is gently pressed,[6] or when the toe is gently compressed along its length[2] or moved.[5] There may be bruising or swelling;[6] sometimes there is a crackling sound.[6] There may be displacement of the bones; the alignment of the nail bed is compared to the same toe on the uninjured foot to check if the toe has rotated (see spiral fracture).[6]

Injuries to the nail bed and neurovascular bundles may be present.[6]

Complications

Malunion, healing with the bones out-of-place, can cause long-term pain and significant disability. Malunion of joint surfaces may cause degenerative joint disease.[2] Malunions may be corrected with or without surgery.[3]

When a toe is broken by crushing, there is often also a subungual hematoma (bleeding/bruising of the nail bed, under the toenail).[3] If there is enough blood to cause pain, it can be drained to relieve the pain and avoid (temporarily) losing the nail.[3] Draining is usually done if the injury is less than 24 hours old. Preserving the nail helps splint the broken toe.[2] Contaminated wounds are more serious; the wound should be kept clean.[8]

Broken toes with open wounds, especially if there is necrosis, can lead to osteomyelitis.[2] Joint problems are more likely in cases of involvement/possible displacement of the joint surface and, in children, involvement of the growth plate.[2] Degenerative arthritis of the distal (outer) big toe joint can occur as a complication of fractures, especially fractures to the proximal (inner) end and diaphysis (midsection) of the proximal bone.[8] If the proximal phalanx of the big toe is broken, hallux valgus (bunion) is a frequent complication.[8]

In high-force crushing and shearing injuries, especially those with open wounds, blood circulation can be impaired.[2]

Causes

Toes usually break because they have been stubbed or crushed.[2][3] Crushing breaks are often caused by dropping something on the toe.[2][3] More rarely, over-extending a toe joint can break off a portion of the bone, and stress fractures are possible,[2] especially just after a sudden increase in activity.[5]

Risk factors

Kicking the ground during sports may result in "turf toe" with an associated broken toe.[10] Getting up suddenly at night, particularly when barefoot, and having a forceful impact with furniture may lead to a broken toe, also called a "bedroom fracture" "nightstand" or "nightwalker fracture".[1][11] Although generally associated with the fifth toe and big toe, it can occur in any toe.[1][12] In such a fracture, the hard blow to the tip of the distal phalanx typically results in a transverse or oblique fracture in the proximal phalanx (base of toe), but can occur in any phalanx.[1][12] An open wound toe fracture may result from an injury from a lawn mower.[4] Although broken toes in horse riders are uncommon, when they do occur it is most likely when standing next to their horse.[13]

Mechanism

Because the big toe is more important for weight-bearing, balance, walking, and running, breaks to the big toe are more likely to be problematic.[6][8] If the big toe is stubbed and breaks, it usually breaks the distal (outermost) bone. A crushing injury can break both big-toe bones.[8]

If the joint was bent too far (i.e. either hyperextended or hyperflexed) then spiral fractures and avulsion fractures are common. Spiral fractures with displacement make the toe rotate and shorten. With transverse fractures (i.e. across the toe), the toe may bend abnormally.[6]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is by direct visualisation and sometimes X-rays.[6] The neighbouring toes and joints are also imaged.[6] In people with multiple traumas, foot trauma is often neglected.[8] Blood circulation may be tested by capillary refill.[2]

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes sprains of ligaments and tendon injuries.[14]

Treatment

It may not be clear whether the toe is broken or just bruised.[15] In such cases the treatment is usually the same in either case.[15]

Removing rings

Any rings on the toes are removed immediately, before the toe starts to swell.[16][17] Pulling rings off forcefully may worsen the swelling. Relaxation, elevation, icing, lubrication (e.g. soapy water or oil), and rotating the ring as if unscrewing it may help. If these methods don't work, it may be possible to remove the ring by temporarily wrapping the toe with a slick thread (something like dental floss), passing the inner end of the thread under the ring and then unwrapping it, pushing the ring ahead of the unwrapping thread. Failing that, the ring may need to cut off.[16][18]

Nonoperative

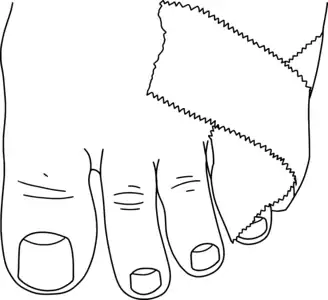

Fractures of the smaller toes are commonly treated by buddy taping (see image). Padding is used between the toes to keep the space dry[3] and the toes aligned comfortably. If the toes are less comfortable when buddy-taped, the buddy tape should be removed.[5] Stiff-soled shoes that protect the toe from bending are also helpful.[3] Fractures with less than 2mm displacement and less than 25% of the area of the joint surface on the broken part are generally also be treated with buddy taping and stiff shoes; the evidence on this treatment is not extensive.[6]

Fractures with displacement at the break, including rotation, can often be reduced (re-aligned) by a family doctor. Some broken toes may need to be put in casts, especially if the fracture is unstable (it won't stay reduced on its own).[2][3] If more than 25% of the area of the joint surface was on the broken-loose part, or the break had to be reduced, follow-up X-rays are done 7–10 days afterwards.[6]

Fractures of the big toe are treated with a short-leg walking boot, or a short-leg walking cast with a sole that protrudes beyond the big toe. These are worn for 2–3 weeks. Buddy taping and a rigid sole are then used for 3–4 weeks, if symptoms allow. At four weeks, range-of-motion exercises can start. If the joint was involved or the break had to be reduced, follow-up X-rays are done a week afterwards.[6]

To reduce pain and swelling,[2] rest, ice, elevation and over-the-counter pain medication are used. The toe is chilled with ice 20 minutes of every hour for the first waking day, and 2-3 times a day afterwards. Ice is not put directly on the skin.[3]

Surgical

Surgery is not needed for most broken toes,[3] but may involve fastening bits of toe bone together with wires, screws, or screwed plates.[8] Such procedures are within the scope of orthopaedic surgery.

Prognosis

Complete healing may take four to six weeks, and complex cases may take up to eight weeks.[3] Some athletes may need longer.[6] Long-term disability is rare.[2] (see complications section).

Epidemiology

Approximately 8 to 9% of all broken bones are of a toe.[4] Studies have varied as to whether broken big toes are more or less common than broken lesser toes.[1] In a UK study involving nearly 6000 fractures seen in hospital, 3.6% were broken toes.[8] Fractures of big toes make up about a fifth[2] or third[6] of all toe fractures, and 5.5% of all foot and ankle fractures in major US trauma hospitals.[8] Toe fractures are the most common foot fractures.[6] About 20% of broken toes involve open wounds.[8]

Other animals

Buddy strapping can be used for toe fractures in big birds.[19] Sometimes a ball bandage can be used, where the bird curls its toes over it.[19] Due to pneumatic bones in birds, washing an open toe fracture may be harmful.[19] Broken toes in grebes can be splinted but if dislocated, often require amputation.[20] A toe fracture in an elephant may go unnoticed.[21][22] Knocked-up toes in racing greyhounds may be mistaken for a toe fracture.[23]

See also

- Foot fractures

- Subungual hematoma (black nail)

- Interphalangeal joints of the foot (toe joints)

- Phalanges (bones of fingers and toes)

- Broken finger

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Carpenter, Brian (2021). "17. Digital fractures". McGlamry's Foot and Ankle Surgery. Vol. 1 (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1342–1347. ISBN 978-1-9751-3606-2. Archived from the original on 2022-06-11. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Hatch, RL; Hacking, S (15 December 2003). "Evaluation and management of toe fractures". American Family Physician. 68 (12): 2413–8. PMID 14705761. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 "Broken toe - self-care: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. US National Library of Medicine. 28 March 2020. Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Eiff, M. Patrice; Hatch, Robert L. (2018). "16. Toe fractures". Fracture Management for Primary Care (Third ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 319–323. ISBN 978-0-323-54655-3. Archived from the original on 2022-06-11. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- 1 2 3 4 "Broken Toe". HealthLink BC. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Bica, D; Sprouse, RA; Armen, J (1 February 2016). "Diagnosis and Management of Common Foot Fractures". American Family Physician. 93 (3): 183–91. PMID 26926612. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ↑ Sueki, Derrick; Brechter, Jacklyn (2009). Orthopedic Rehabilitation Clinical Advisor. Maryland Hights: Elsevier. p. 686. ISBN 978-0-323-05710-3. Archived from the original on 2022-06-11. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Godoy-Santos, AL; Giordano, V; Cesar, C; Sposeto, RB; Bitar, RC; Wajnsztejn, A; Sakaki, MH; Fernandes, TD (November 2020). "Hallux Proximal Phalanx Fracture in Adults: An Overlooked Diagnosis". Acta Ortopedica Brasileira. 28 (6): 318–322. doi:10.1590/1413-785220202806236612. PMC 7723381. PMID 33328790.

- 1 2 Meinberg, Eg; Agel, J; Roberts, Cs; Karam, Md; Kellam, Jf (January 2018). "Fracture and Dislocation Classification Compendium—2018" (PDF). Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 32 (1): S1–S10. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000001063. PMID 29256945. S2CID 39138324. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2022-04-14., page 99 of PDF fulltext

- ↑ Rowe, Lindsay J. (1995). "4. Imaging". In Logan, Alfred L.; Rowe, Lindsay J. (eds.). The Foot and Ankle: Clinical Applications. Gaithersburg, Maryland: Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 76–78. ISBN 0-8342-0605-6. Archived from the original on 2022-06-11. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- ↑ Schnaue-Constantouris, Eileen M.; Birrer, Richard B.; Grisafi, Patrick J.; Dellacorte, Michael P. (1 February 2002). "Digital foot trauma: emergency diagnosis and treatment1". Journal of Emergency Medicine. 22 (2): 163–170. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(01)00458-9. ISSN 0736-4679. PMID 11858921. Archived from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- 1 2 Yochum, Terry R.; Rowe, Lindsay J.; Maola, Chad J. (2005). "9. Trauma". In Yochum, Terry R.; Rowe, Lindsay J. (eds.). Essentials of skeletal radiology (Third ed.). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 881–884. Archived from the original on 2022-06-11. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- ↑ Ceroni, Dimitri (1 January 2007). "Support and safety features in preventing foot and ankle injuries in equestrian sports : review article". International SportMed Journal. 8 (3): 166–178. hdl:10520/EJC48619. Archived from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ↑ Hatch, Robert L.; Hacking, Scott (15 December 2003). "Evaluation and Management of Toe Fractures". American Family Physician. 68 (12): 2413–2418. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 14705761. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- 1 2 "Broken toe". nhs.uk. UK National Health Service. 17 October 2017. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- 1 2 "Toe Injury". Seattle Children’s Hospital. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ↑ Zuber, Thomas J.; Mayeaux, E. J. (2004). "6. Ring removal". Atlas of Primary Care Procedures. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-7817-3905-4. Archived from the original on 2022-06-11. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- ↑ "Removing a Ring From a Finger or Toe". HealthLink BC. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Sirois, Margi (2021). "13. Avian and exotic animal care and nursing". Elsevier's Veterinary Assisting Textbook (3rd ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-323-68145-2. Archived from the original on 2022-06-11. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- ↑ Duerr, Rebecca S.; Gage, Laurie J. (2020). Hand-Rearing Birds (2nd ed.). Hoboken: Wiley Blckwell. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-119-16775-4.

- ↑ Fowler, Murray E. (2008). "20. Foot disorders". In Fowler, Murray E.; Mikota, Susan K. (eds.). Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of Elephants. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-8138-0676-1. Archived from the original on 2022-06-11. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- ↑ Regnault, Sophie; Dixon, Jonathon J.I.; Warren-Smith, Chris; Hutchinson, John R.; Weller, Renate (18 January 2017). "Skeletal pathology and variable anatomy in elephant feet assessed using computed tomography". PeerJ. 5: e2877. doi:10.7717/peerj.2877. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5248576. PMID 28123909.

- ↑ McCunn, J.; Formston, C. (1 March 1931). ""Knocked -Up Toe" in Racing Greyhounds". The Veterinary Journal (1900). 87 (3): 144–147. doi:10.1016/S0372-5545(17)40566-9. ISSN 0372-5545. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.