Lung cavity

| Lung cavity | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Pulmonary cavity, lung cavitary lesion, lung cavitation |

| |

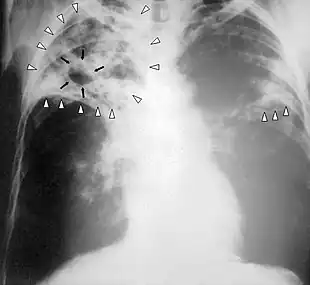

| Chest X-ray of a person with advanced tuberculosis: Infection in both lungs is marked by white arrow-heads, and the formation of a cavity is marked by black arrows. | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

A lung cavity or pulmonary cavity is an abnormal, thick-walled, air-filled space within the lung.[1] Cavities in the lung can be caused by infections, cancer, autoimmune conditions, trauma, congenital defects,[2] or pulmonary embolism.[3] The most common cause of a single lung cavity is lung cancer.[4] Bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal infections are common causes of lung cavities.[5] Globally, tuberculosis is likely the most common infectious cause of lung cavities.[6] Less commonly, parasitic infections can cause cavities.[5] Viral infections almost never cause cavities.[7] The terms cavity and cyst are frequently used interchangeably; however, a cavity is thick walled (at least 5 mm), while a cyst is thin walled (4 mm or less). The distinction is important because cystic lesions are unlikely to be cancer, while cavitary lesions are often caused by cancer.[3]

Diagnosis of a lung cavity is made with a chest X-ray or CT scan of the chest,[2] which helps to exclude mimics like lung cysts, emphysema, bullae, and cystic bronchiectasis.[5] Once an imaging diagnosis has been made, a person’s symptoms can be used to further narrow the differential diagnosis. For example, recent onset of fever and productive cough suggest an infection, while a chronic cough, fatigue, and unintentional weight loss suggest cancer or tuberculosis.[2] Symptoms of a lung cavity due to infection can include fever, chills, and cough.[5] Knowing how long someone has had symptoms for or how long a cavity has been present on imaging can also help to narrow down the diagnosis. If symptoms or imaging findings have been present for less than three months, the cause is most likely an acute infection; if they have been present for more than three months, the cause is most likely a chronic infection, cancer, or an autoimmune disease.[5]

The presence of lung cavities is associated with worse outcomes in lung cancer[7] and tuberculosis;[8] however, if a lung cancer develops cavitation after chemotherapy and radiofrequency ablation, that indicates a good response to treatment.[2]

Formal definition

In the 2008 Fleischner Society "Glossary of Terms for Thoracic Imaging", a cavity is radiographically defined as “a gas-filled space, seen as a lucency or low-attenuation area, within [a] pulmonary consolidation, a mass, or a nodule”.[9] Pathologically, a cavity is “usually produced by the expulsion or drainage of a necrotic part of the lesion via the bronchial tree.”[9]

Lung cavity mimics

The first step in evaluating a suspected lung cavity lesion is to exclude other kinds of abnormal air-filled spaces in the lung, including lung cysts, emphysema, bullae, and cystic bronchiectasis.[5] Lung cysts are the most common mimics of lung cavities.[2] Cavities and cysts are similar in that they are both abnormal, air-containing spaces with clearly defined walls.[3] The difference between cavities and cysts is that cavities are thick walled, while cysts are thin walled.[3] Generally, cavities have walls that are at least 5 mm thick, while cysts have walls that are 4 mm or less,[3] and often less than 2 mm.[2]

The distinction between cysts and cavities is important because the thicker the wall is, the more likely it is to be cancer. Thus, cystic lesions are unlikely to be cancer, while cavitary lesions are often caused by cancer.[3] In a study from 1980 that used chest X-rays to evaluate 65 cases of solitary lung cavities, 0% percent of cavities with walls 1 mm or less were malignant (that is, cancerous), versus 8% of cavities with walls 4 mm or less, 49% of cavities with walls 5 to 15 mm, and 95% of cavities with walls 15 mm or greater.[3] However, a 2007 study that used CT to evaluate lung cavities showed no relationship between wall thickness and the likelihood of malignancy.[5] It did show that malignant cavities are more likely than benign cavities to have an irregular internal wall (49% vs 26%) and have an indentation of the outer wall of the cavity (54% vs 29%).[5]

Areas of emphysema are abnormal, air-filled spaces that usually do not have visible walls,[5] and bullae are very thin walled (<1 mm).[2] Cystic bronchiectasis is irreversible bronchial dilation, which is permanent widening of the bronchioles (small airways) in the lung.[2] It can be distinguished on imaging by a lack of bronchial tapering, meaning that the bronchioles do not get narrower as they travel further into the lung. Cystic bronchiectasis is also associated with an increased bronchoarterial ratio, meaning that the bronchioles are larger than the blood vessels that run alongside them.[5]

Infectious causes

Bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal infections are common causes of lung cavities.[5] Globally, tuberculosis is likely the most common infectious cause of lung cavities.[6] Less commonly, parasitic infections can cause cavities.[5] Viral infections almost never cause lung cavities; in a small study of immunocompromised patients with a lung infection, the presence of a cavity on CT scan essentially ruled out viral infection. In the same study, about one-third of the cavities were caused by a bacterial infection, another third were caused by a mycobacterial infection, and another third were caused by a fungal infection.[7]

Bacterial

Bacteria can cause lung cavities in one of two ways; they can either enter the lung through the trachea (windpipe), or they can enter through the bloodstream as septic pulmonary emboli (infected blood clots).[7] Community-acquired pneumonia is an uncommon cause of lung cavities, but cavitary pneumonia is occasionally seen with Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae infection. However, since these two species of bacteria are such common causes of pneumonia, they may cause a significant fraction of all cavitary pneumonias.[7] The most common bacterial causes of lung cavities are Streptococcus species and Klebsiella pneumoniae.[5] Less commonly, the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter, Escherichia coli, and Legionella can cause cavitation.[5] Nocardia is a bacterium that can cause pulmonary nocardiosis and lung cavities in people who are immunocompromised (have weak immune systems), including organ transplant recipients who are on immunosuppressants, and those with AIDS, lymphoma, or leukemia.[5] Melioidosis, caused by the bacteria Burkholderia pseudomallei, is common in tropical areas, especially Southeast Asia, and is frequently associated with lung cavities.[7]

Pneumonia can lead to the development of a lung abscess,[4] which is a pus-containing necrotic lesion of the lung parenchyma (lung tissue).[5] On CT scan of the chest, a lung abscess appears as an intermediate- or thick-walled cavity with or without an air-fluid level (a flat line separating the air in the cavity from the fluid).[4] An abscess can occur anywhere in the lung.[4] Risk factors for polymicrobial lung abscesses (abscesses caused by multiple species of bacteria) include alcoholism, a history of aspiration (food or water accidentally going down the trachea), poor dentition (bad teeth),[7] older age, diabetes mellitus, drug abuse, and artificial ventilation.[2] Polymicrobial lung abscesses are usually due to aspiration and are located in the posterior segments of the upper lobes or superior segments of the lower lobes.[2] Klebsiella pneumoniae is a common cause of lung abscesses and is usually monomicrobial (caused by a single species of bacteria). Risk factors include diabetes and chronic lung disease.[7] A lung abscess due to Klebsiella can progress to massive pulmonary gangrene, a rare condition in which an entire section of the lung is completely destroyed. Half of all cases of pulmonary gangrene are caused by Klebsiella. Imaging in pulmonary gangrene shows multiple small cavities joining together to form a large cavity.[7]

Mycobacterial

Mycobacteria that can cause cavitations include Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria, most commonly Mycobacterium avium complex.[7] Primary tuberculosis is caused by the initial infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and rarely results in the formation of lung cavities. 90% of people with primary tuberculosis are able to contain the infection and enter a latent phase. Reactivation tuberculosis, which is caused by the reactivation of latent tuberculosis,[2] results in lung cavities visible on X-ray 30 to 50% of the time.[7] There are frequently multiple cavities, and they most commonly occur in the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes or the superior segment of the lower lobes.[7] Cavitary tuberculosis is associated with worse outcomes, a higher rate of treatment failure, more frequent relapse after treatment, and a higher risk of transmitting the disease to others.[8] Even after successful treatment with anti-tuberculosis drugs, 20-50% of patients with cavitary tuberculosis have persistent cavities, which results in decreased lung function and increased risk of opportunistic infections by Aspergillus fumigatus and other fungal pathogens.[8]

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are all mycobacterial species other than Mycobacteria tuberculosis (which causes tuberculosis) and Mycobacterium leprae (which causes leprosy).[6] NTM are found everywhere in the environment but are most commonly found in soil and water.[5] Lung disease is caused by inhaling or ingesting nontuberculous mycobacteria. Unlike tuberculosis, NTM infection is not transmitted from person to person.[6] Although NTM lung infections can cause lung cavities, the most common finding on imaging is bronchiectasis, which may occur with or without cavities.[10] Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) is the most common cause of NTM lung disease in most countries, including the United States.[6] Classically, MAC infection results in either upper lobe cavities in male smokers with COPD or bronchiectasis in thin, older women; however, it is possible to have both cavities and bronchiectasis in the same patient.[10] Similar to tuberculosis, the presence of cavities in MAC infection is associated with worse outcomes.[6] Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium xenopi, and the rapidly-growing Mycobacterium abscessus have also been associated with lung cavities.[6]

Fungal

Fungal infections that can cause cavitations include histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis, cryptococcosis, and aspergillosis.[2] Aspergillosis, most commonly caused by Aspergillus fumigatus, can present in four different ways (listed in order of increasing severity): aspergilloma, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), chronic necrotizing aspergillosis, and invasive aspergillosis. All of these are associated with lung cavities except for ABPA,[7] which is a hypersensitivity response associated with bronchiectasis on imaging.[2] An aspergilloma is an infection of a pre-existing lung cavity by Aspergillus species without tissue invasion and results in the formation of a fungal ball.[2] Historically, tuberculosis was the most common cause of the lung cavity (and still is in areas where tuberculosis is endemic);[7] however, the cavity can also be caused by sarcoidosis, bullae, bronchiectasis, or cystic lung disease.[2] Chronic necrotizing aspergillosis and invasive aspergillosis are usually seen in immunocompromised people.[4] Risk factors for chronic necrotizing aspergillosis include advanced age, alcoholism, diabetes, and mild immunosuppression.[7] Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is mainly seen in severely immunocompromised people, especially those with hematological malignancies (cancers of the blood), bone marrow transplant recipients, and people on long-term corticosteroid therapy, such as prednisone. Allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients have the highest risk of getting invasive aspergillosis. Lung transplant recipients are also at high risk.[7]

Parasitic

Parasitic infections associated with cavitations include echinococcosis and paragonimiasis.[7] Echinococcus is a tapeworm that most commonly infects dogs; people become infected by ingesting food or water that contains Echinococcus eggs. This results in cysts forming in the body, most commonly in the liver, but lung involvement is seen in 10-30% of cases. The cysts in the lung sometimes look like cavities on imaging.[7] Paragonimus westermani, also called the lung fluke, is a flatworm which is transmitted by eating freshwater crabs or crayfish containing metacercaria (the infective form of the tapeworm). They mature into adult lung flukes in the lung, where cavitations may be seen in 15-59% of cases. Paragonimiasis is common in East Asia and Southeast Asia.[7]

Noninfectious causes

Lung cancer

The most common cause of a single lung cavity is lung cancer.[4] Usually, the cavity forms because the cancer grows more rapidly then its blood supply, resulting in necrosis (cell death) in the central part of the cancer. 81% of lung cancers that develop cavities over-express epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which could be related to rapid growth, central necrosis, and cavity formation.[11] 11% of primary lung cancers (cancers that start in the lung) have cavities that can be seen on chest X-ray; 22% of primary lung cancers will have cavities on CT, which is more sensitive.[2] Squamous-cell carcinoma of the lung is more likely to develop cavitations than lung adenocarcinoma or large-cell lung carcinoma.[2] Other primary cancers of the lung, such as lymphoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma, can also cavitate, especially in people with AIDS.[7] Lung cancers that develop cavities are associated with a poor prognosis (worse outcomes). Cancers that metastasize (spread) to the lung can also develop cavitations, but this is only seen about 4% of the time on X-ray. Metastatic cancers of squamous cell origin are also more likely to cavitate than cancers of other origins.[7] Both chemotherapy (drugs to treat cancer) and radiofrequency ablation (destroying cancer with radio waves) can cause lung cancers to develop cavities, which is a sign of a good response to treatment.[2] It is possible to have both an infection and lung cancer in the same cavity; the most common combination is primary lung cancer and tuberculosis.[7]

Autoimmune

Autoimmune causes of lung cavities include granulomatosis with polyangiitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and rarely necrotizing sarcoidosis[2] (less than 1% of people with sarcoidosis develop lung cavities).[4] Ankylosing spondylitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and systemic lupus erythematous rarely cause lung cavities.[2]

Pulmonary embolism and septic emboli

Pulmonary embolism (a blood clot in the lung) causes pulmonary infarction (the death of lung tissue) less than 15% of the time, and only about 5% of pulmonary infarctions result in lung cavities.[3] Septic pulmonary emboli (infected blood clots) are collections of infectious organisms, fibrin, and platelets[7] that travel through the blood to the lung and cause small areas of pulmonary infarction by blocking off blood flow. This results in multiple small cavities 85% of the time.[5] Symptoms can include cough, dyspnea (shortness of breath), chest pain, hemoptysis (coughing up blood) and sinus tachycardia (a fast heart rate).[4] Risk factors for septic pulmonary emboli include IV drug use, implanted prosthetic devices (like central lines, pacemakers, and right-sided heart valves), and septic thrombophlebitis (a blood clot in a vein due to infection). Two forms of septic thrombophlebitis include pelvic thrombophlebitis and Lemierre's syndrome (septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein).[7]

Trauma

Pulmonary contusion (lung bruise) from blunt chest trauma causes bleeding into the alveoli (air sacs) and can cause small cavities to form that are called traumatic pulmonary pseudocysts (TPP). This is rare, as less than 3% of lung injuries lead to TPP. It can occur at any age, but is more common in children and adults under the age of 30. Although it can occur anywhere in the lung, it is most common in the lower lobes. TPP usually resolves on its own within four weeks.[2]

Congenital

Congenital lung cavities, or lung cavities present at birth, include bronchogenic cysts, congenital pulmonary airway malformation, and pulmonary sequestration.[2] These congenital lesions are the most common cause of lung cavities in infants, children, and young adults. Bronchogenic cysts are due to abnormal budding of the bronchial tree. About 70% are found in the mediastinum, which is the central part of the chest where the heart is. Another 15 to 20% are intrapulmonary (within the lung), usually in the lower lobes.[2] Congenital pulmonary airway malformation, formerly called congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, is a benign tumor the results in the formation of single or multiple cysts.[2] Pulmonary sequestration refers to abnormal lung tissue that gets its blood supply from the systemic circulation instead of the pulmonary circulation, like the rest of the lung. This lung tissue is also not connected to the trachea.[2]

See also

- Focal lung pneumatosis, article comparing lung blebs, bullae, cysts, and cavities

References

- ↑ Bell, Daniel, Gaillard, Frank. "Pulmonary cavities". Radiopedia. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Canan A, Batra K, Saboo S, Landay M, Kandathil A (15 September 2020). "Radiological approach to cavitary lung lesions". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 97 (1150): 521–531. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138694. PMID 32934178. S2CID 221747977.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ryu J, Swensen S (June 2003). "Cystic and Cavitary Lung Diseases: Focal and Diffuse". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 78 (6): 744–752. doi:10.4065/78.6.744. PMID 12934786.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Parkar AP, Kandiah P (19 November 2016). "Differential Diagnosis of Cavitary Lung Lesions". Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology. 19 (100): 100. doi:10.5334/jbr-btr.1202. PMC 6100641. PMID 30151493.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Gafoor K, Patel S, Girvin F, Gupta N, Naidich D, Machnicki S, Brown KK, Mehta A, Husta B, Ryu JH, Sarosi GA, Franquet T, Verschakelen J, Johkoh T, Travis W, Raoof S (June 2018). "Cavitary Lung Diseases: A Clinical-Radiologic Algorithmic Approach". Chest. 153 (6): 1443–1465. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2018.02.026. PMID 29518379.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Holt MR, Chan ED (September 2018). "Chronic Cavitary Infections Other than Tuberculosis: Clinical Aspects". Journal of Thoracic Imaging. 33 (5): 322–333. doi:10.1097/RTI.0000000000000345. PMID 30036298. S2CID 51714091.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Gadkowski, L. Beth; Stout, Jason E. (9 April 2008). "Cavitary pulmonary disease". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 21 (2): 305–333. doi:10.1128/CMR.00060-07. PMC 2292573. PMID 18400799.

- 1 2 3 Urbanowski ME, Ordonez AA, Ruiz-Bedoya CA, Jain SK, Bishai WR (June 2020). "Cavitary tuberculosis: the gateway of disease transmission". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 20 (6): e117–e128. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30148-1. PMC 7357333. PMID 32482293.

- 1 2 Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J (March 2008). "Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging". Radiology. 246 (3): 697–722. doi:10.1148/radiol.2462070712. PMID 18195376.

- 1 2 Ketai L, Currie BJ, Holt MR, Chan ED (September 2018). "Radiology of Chronic Cavitary Infections". Journal of Thoracic Imaging. 33 (5): 334–343. doi:10.1097/RTI.0000000000000346. PMID 30048346. S2CID 51723111.

- ↑ Gill R, Matsusoka S, and Hatabu H (9 June 2010). "Cavities in the Lung in Oncology Patients: Imaging Overview and Differential Diagnoses". Applied Radiology.