Enchondroma

| Enchondroma | |

|---|---|

| |

| MRI T1 showing an enchondroma in the femur | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Often none, pain, swelling[1] |

| Complications | Broken bone[1] |

| Types | Solitary, multiple (enchondromatosis)[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging[1] |

| Treatment | Observation, curettage, bone graft[2] |

| Prognosis | Usually good[2] |

| Frequency | 30% of cartilage tumors[3] |

Enchondroma is a type of non-cancerous bone tumor belonging to the group of cartilage tumors.[4][5] It is often detected on medical imaging when investigating another problem, as there are usually no symptoms.[6] Some may however present with a swelling, pain or unexplained broken bone, typically in the short tubular bones of the hands.[1]

Diagnosis is by X-ray, CT scan and sometimes MRI.[1] Most occur as a smaller than 3cm size single tumor.[1] When several occur in one long bone or several bones, the syndrome is called enchondromatosis.[1]

Where there are no symptoms, treatment is often not needed.[1] If treatment is required, the enchondroma can be surgically scraped out.[1] Less than 1% become malignant, unless part of a syndrome.[1]

They comprise around 30% of cartilage tumors,[3] and about 90% of tumors in the hand.[7]

Signs and symptoms

Enchondroma is often detected on medical imaging when investigating another problem, as there are usually no symptoms.[2][6] Some present with a swelling, pain or unexplained broken bone, when it typically occurs in the short tubular bones of the hands.[1] Most occur as a single tumor.[1] When several occur in one long bone or several bones, the syndrome is called enchondromatosis.[1]

The conditions that involve multiple lesions include Ollier disease and Maffucci's syndrome.[2]

Cause

While the exact cause of enchondroma is not known, it is believed to occur either as an overgrowth of the cartilage that lines the ends of the bones, or as a persistent growth of original, embryonic cartilage.

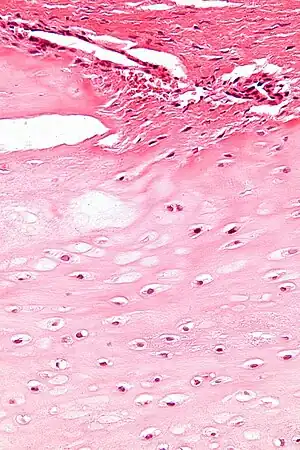

Pathophysiology

Enchondroma is a type of non-cancerous bone tumor that originates from cartilage.[1] An enchondroma most often affects the cartilage that lines the inside of the bones. The bones most often involved with this benign tumor are the miniature long bones of the hands and feet. It may, however, also involve other bones such as the femur, humerus, or tibia. While it may affect an individual at any age, it is most common in adulthood. The occurrence between males and females is equal. It is not very likely that the enchondroma will grow back in the same spot; the rate is less than ten percent.

Diagnosis

Diagnosistic tests include medical imaging.[2] Appearances on X-ray show a small lobe-shaped, dark tumor in the middle of the bone.[2] It typically contains white spots; calcified chondroid matrix (a "rings and arcs" pattern of calcification).[2] It does not extend into soft tissues.[6] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and CT scan may be requested to further evaluate the tumor.[8]

Bone scan may rule out any infection or fractures.

X-ray: Solitary enchondroma in long bone of thigh near knee

X-ray: Solitary enchondroma in long bone of thigh near knee

.jpg.webp) Multiple (enchondromatosis) in fingers

Multiple (enchondromatosis) in fingers

Differential diagnosis

Differentiating an enchondroma from a bone infarct on plain film may be difficult. Generally, an enchondroma commonly causes endosteal scalloping while an infarct will not. An infarct usually has a well-defined, sclerotic serpentine border, while an enchondroma will not. When differentiating an enchondroma from a chondrosarcoma, the radiographic image may be equivocal; however, periostitis is not usually seen with an uncomplicated enchondroma.

Treatment

Where there are no symptoms, treatment is often not needed. If treatment is required, the enchondroma can be surgically scraped out.[2] Subsequent bone grafting may be needed.[2]

If there is no sign of bone weakening or growth of the tumor, observation only may be suggested. However, follow-up with repeat x-rays may be necessary. Some types of enchondromas can develop into malignant, or cancerous, bone tumors later. Careful follow-up with a physician may be recommended.

Specific treatment for enchondroma be affected by the age, overall health, and medical history of the affected person. Other considerations include extent of the disease, tolerance for therapies, expectations for the course of the disease, and opinion or preference of the affected person.

Outcome

Less than 1% become malignant, unless part of a syndrome.[1]

Epidemiology

Enchondromas account for around 30% of cartilage tumors, the most common type of non-cancerous bone tumor.[3] 35% of enchondromas occur in the hand and 90% of tumors in the hand are enchondromas.[7] They account for 12% to 24% of primary bone tumors.[6]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. (2020). "Enchondroma". Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours. Vol. 3 (5th ed.). Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. pp. 353–355. ISBN 978-92-832-4503-2. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Enchondroma - OrthoInfo - AAOS". www.orthoinfo.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 Engel, Hannes; Herget, Georg W.; Füllgraf, Hannah; Sutter, Reto; Benndorf, Matthias; Bamberg, Fabian; Jungmann, Pia M. (March 2021). "Chondrogenic Bone Tumors: The Importance of Imaging Characteristics". RoFo: Fortschritte Auf Dem Gebiete Der Rontgenstrahlen Und Der Nuklearmedizin. 193 (3): 262–275. doi:10.1055/a-1288-1209. ISSN 1438-9010. PMID 33152784. Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- ↑ WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. (2020). "Bone tumors". Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours. Vol. 3 (5th ed.). Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. p. 338. ISBN 978-92-832-4503-2. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ↑ "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Suster, David; Hung, Yin Pun; Nielsen, G. Petur (1 January 2020). "Differential Diagnosis of Cartilaginous Lesions of Bone". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 144 (1): 71–82. doi:10.5858/arpa.2019-0441-RA. ISSN 0003-9985. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- 1 2 Pal, Julie; Wallman, Jackie (2019). "33. Ganglions and tumours of the hands and wrist". In Wietlisbach, Christine M. (ed.). Cooper'sFundamentals of Hand Therapy E-Book: Clinical Reasoning and Treatment Guidelines for Common Diagnoses of the Upper Extremity. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-323-52479-7. Archived from the original on 2021-07-19. Retrieved 2021-07-08.

- ↑ Wang XL, De Beuckeleer LH, De Schepper AM, Van Marck E (2001). "Low-grade chondrosarcoma vs enchondroma: challenges in diagnosis and management". European Radiology. 11 (6): 1054–1057. doi:10.1007/s003300000651. PMID 11419152.

External links

| Classification |

|

|---|---|

| External resources |