Polio eradication

Polio eradication, the permanent global cessation of circulation by the poliovirus and hence elimination of the poliomyelitis (polio) it causes, is the aim of a multinational public health effort begun in 1988, led by the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the Rotary Foundation.[1] These organizations, along with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and The Gates Foundation, have spearheaded the campaign through the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Successful eradication of infectious diseases has been achieved twice before, with smallpox[2] and bovine rinderpest.[3]

Prevention of disease spread is accomplished by vaccination. There are two kinds of polio vaccine—oral polio vaccine (OPV), which uses weakened poliovirus, and inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), which is injected. The OPV is less expensive and easier to administer, and can spread immunity beyond the person vaccinated, creating contact immunity. It has been the predominant vaccine used. However, under conditions of long-term vaccine virus circulation in under-vaccinated populations, mutations can reactivate the virus to produce a polio-inducing strain, while the OPV can also, in rare circumstances, induce polio or persistent asymptomatic infection in vaccinated individuals, particularly those who are immunodeficient. Being inactivated, the IPV is free of these risks but does not induce contact immunity. IPV is more costly and the logistics of delivery are more challenging.

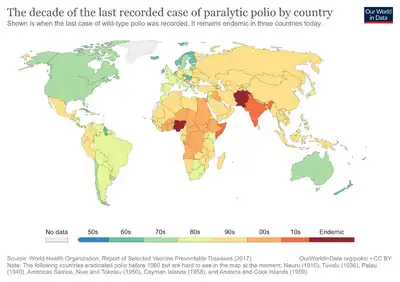

Nigeria is the latest country to have officially stopped endemic transmission of wild poliovirus, with its last reported case in 2016.[4] Wild poliovirus has been eradicated in all continents except Asia, and as of 2020, Afghanistan and Pakistan are the only two countries where the disease is still classified as endemic.[5][6]

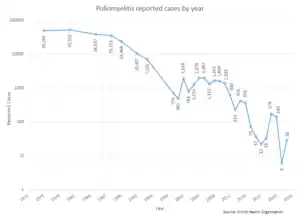

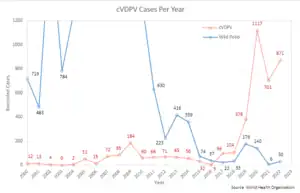

Recent polio cases arise from two sources, the original 'wild' poliovirus (WPV), and mutated oral vaccine strains, so-called circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV). There were 140 diagnosed WPV cases worldwide in 2020, a decrease from 2019's 5-year high, an 81% reduction from the 719 diagnosed cases in 2000 and a 99.96% reduction from the estimated 350,000 cases when the eradication effort began in 1988. Of the three strains of WPV, the last recorded wild case caused by type 2 (WPV2) was in 1999, and WPV2 was declared eradicated in 2015. Type 3 (WPV3) is last known to have caused polio in 2012, and was declared eradicated in 2019.[7] All wild-virus cases since that date have been due to type 1 (WPV1). Vaccines against each of the three types have given rise to emergent strains of cVDPV, with cVDPV2 being most prominent, and such strains caused over 1,000 polio cases in 2020.

Factors influencing eradication of polio

Eradication of polio has been defined in various ways—as elimination of the occurrence of poliomyelitis even in the absence of human intervention,[8] as extinction of poliovirus, such that the infectious agent no longer exists in nature or in the laboratory,[9] as control of an infection to the point at which transmission of the disease ceased within a specified area,[8] and as reduction of the worldwide incidence of poliomyelitis to zero as a result of deliberate efforts, and requiring no further control measures.[10]

In theory, if the right tools were available, it would be possible to eradicate all infectious diseases that reside only in a human host. In reality, there are distinct biological features of the organisms and technical factors of dealing with them that make their potential eradicability more or less likely. Three indicators, however, are considered of primary importance in determining the likelihood of successful eradication: that effective interventional tools are available to interrupt transmission of the agent, such as a vaccine; that diagnostic tools, with sufficient sensitivity and specificity, be available to detect infections that can lead to transmission of the disease; and that humans are required for the life-cycle of the agent, which has no other vertebrate reservoir and cannot amplify in the environment.[11]

Strategy

The most important step in eradication of polio is interruption of endemic transmission of poliovirus. Stopping polio transmission has been pursued through a combination of routine immunization, supplementary immunization campaigns and surveillance of possible outbreaks. Several key strategies have been outlined for stopping polio transmission:[12]

- High infant immunization coverage with four doses of oral polio vaccine (OPV) in the first year of life in developing and endemic countries, and routine immunization with OPV and/or IPV elsewhere.

- Organization of "national immunization days" to provide supplementary doses of oral polio vaccine to all children less than five years old.

- Active surveillance for poliovirus through reporting and laboratory testing of all cases of acute flaccid paralysis. Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) is a clinical manifestation of poliomyelitis characterized by weakness or paralysis and reduced muscle tone without other obvious cause (e.g., trauma) among children less than fifteen years old. Other pathogenic agents can also cause AFP, such as enteroviruses, echoviruses, and adenoviruses.[13]

- Expanded environmental surveillance to detect the presence of poliovirus in communities.[14] Sewage samples are collected at regular and random sites and tested in laboratories for the presence of WPV or cVDPV. Since most polio infections are asymptomatic, transmission can occur in spite of the absence of polio-related AFP cases, and such monitoring helps to evaluate the degree to which virus continues to circulate in an area.

- Targeted "mop-up" campaigns once poliovirus transmission is limited to specific geographical foci.

Vaccination

There are two distinct types of polio vaccine. Oral polio vaccine (OPV, or Sabin vaccine) contains attenuated poliovirus, 10,000 times less able to enter the circulation and cause polio,[15] delivered as oral drops or infused into sugar cubes. It is highly effective and inexpensive (about US$0.12 per dose in 2016[15]) and its availability has bolstered efforts to eradicate polio. A study carried out in an isolated Inuit village showed that antibodies produced from subclinical wild virus infection persisted for at least 40 years.[16] Because the immune response to oral polio vaccine is very similar to that of natural polio infection, it is expected that oral polio vaccination provides similar lifelong immunity to the virus.[17][18] Because of its route of administration, it induces an immunization of the intestinal mucosa that protects against subsequent infection, though multiple doses are necessary to achieve effective prophylaxis.[15] It can also produce contact immunity. Attenuated poliovirus derived from the oral polio vaccine is excreted, infecting and indirectly inducing immunity in unvaccinated individuals, and thus amplifying the effects of the doses delivered.[19] The oral administration does not require special medical equipment or training. Taken together, these advantages have made it the favored vaccine of many countries, and it has long been preferred by the global eradication initiative.[15]

The primary disadvantage of OPV derives from its inherent nature. As an attenuated but active virus, it can induce vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP) in approximately one individual per every 2.4 million doses administered.[20] Likewise, mutation during the course of persistent circulation in undervaccinated populations can lead to vaccine-derived poliovirus strains (cVDPV) that can induce polio at much higher rates than the original vaccine.[20] Until recent times, a trivalent OPV containing all three virus strains was used, but with the eradication of wild poliovirus type 2 this was phased out in 2016 and replaced with bivalent vaccine containing just types 1 and 3, supplemented with monovalent type 2 OPV in regions with documented cVDPV2 circulation.[15] A novel OPV2 vaccine (nOPV2) genetically modified to reduce the likelihood of disease-causing activating mutations was introduced in March 2021 on a limited basis, and later in the year it was recommended for expanded use, with full rollout expected in 2023.[21]

The inactivated polio vaccine (IPV, or Salk) contains trivalent fully inactivated virus, administered by injection. This vaccine cannot induce VAPP nor do cVDPV strains arise from it, but it likewise cannot induce contact immunity and thus must be administered to every individual. Added to this are greater logistical challenges. Though a single dose is sufficient for protection, administration requires medically trained vaccinators armed with single-use needles and syringes. Taken together, these factors result in substantially higher delivery costs.[22] Original protocols involved intramuscular injection in the arm or leg, but recently subcutaneous injection using a lower dose (so-called fractional-dose IPV, fIPV) has been found to be effective, lowering costs and also allowing for more convenient and cost-effective delivery systems.[23][24] The use of IPV results in serum immunity, but no intestinal immunity arises. As a consequence, vaccinated individuals are protected from contracting polio, but their intestinal mucosa may still be infected and serve as a reservoir for the excretion of live virus. For this reason, IPV is ineffective at halting ongoing outbreaks of WPV or cVDPV, but it has become the vaccine of choice for industrialized, polio-free countries.[22]

While IPV does not itself induce mucosal immunity, it has been shown to boost the mucosal immunity from OPV,[25] and the WHO now favors a combined protocol. It is recommended that vulnerable children receive a dose of OPV at birth, then beginning at the age of six weeks a 'primary series' consisting of three OPV doses at least four weeks apart, along with one dose of IPV after 14 weeks.[20] This combined IPV/OPV approach has also been used in outbreak suppression.[26]

Herd immunity

Polio vaccination is also important in the development of herd immunity.[27] For polio to occur in a population, there must be an infecting organism (poliovirus), a susceptible human population, and a cycle of transmission. Poliovirus is transmitted only through person-to-person contact, and the transmission cycle of polio is from one infected person to another person susceptible to the disease.[19] If the vast majority of the population is immune to a particular agent, the ability of that pathogen to infect another host is reduced; the cycle of transmission is interrupted, and the pathogen cannot reproduce and dies out. This concept, called community immunity or herd immunity, is important to disease eradication, because it means that it is not necessary to inoculate 100% of the population—a goal that is often logistically very difficult—to achieve the desired result. If the number of susceptible individuals can be reduced to a sufficiently small number through vaccination, then the pathogen will eventually die off.[28]

When many hosts are vaccinated, especially simultaneously, the transmission of wild virus is blocked, and the virus is unable to find another susceptible individual to infect. Because poliovirus can only survive for a short time in the environment (a few weeks at room temperature, and a few months at 0–8 °C (32–46 °F)), without a human host, the virus dies out.[29]

Herd immunity is an important supplement to vaccination. Among those individuals who receive oral polio vaccine, only 95 percent will develop immunity after three doses.[30] This means that five of every 100 given the vaccine will not develop any immunity and will be susceptible to developing polio. According to the concept of herd immunity, the population for whom the vaccine fails is still protected by the immunity of those around them. Herd immunity may only be achieved when vaccination levels are high.[27] It is estimated that 80–86 percent of individuals in a population must be immune to polio for the susceptible individuals to be protected by herd immunity.[27] If routine immunization were to be stopped, the number of unvaccinated, susceptible individuals would soon exceed the capability of herd immunity to protect them.[31]

Vaccine-derived poliovirus

(before 2000 may include small numbers of cVDPV cases)

While vaccination has played an instrumental role in the reduction of polio cases worldwide, the use of attenuated virus in the oral vaccine carries with it an inherent risk. The oral vaccine is a powerful tool in fighting polio in part because of its person-to-person transmission and resulting contact immunity. However, under conditions of long-term circulation in undervaccinated populations, the virus can accumulate mutations that reverse the attenuation and result in vaccine virus strains that themselves cause polio. As a result of such circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) strains, polio outbreaks have periodically recurred in regions that have long been free of the wild virus, but where vaccination rates have fallen. Oral vaccines can also give rise to persistent infection in immunodeficient individuals, with the virus eventually mutating into a more virulent immunodeficiency-associated vaccine-derived poliovirus (iVDPV). In particular, the type 2 strain seems prone to reversions, so in 2016 the eradication effort abandoned the trivalent oral vaccine containing attenuated strains of all three virus types and replaced it with a bivalent oral vaccine lacking the type 2 virus, while a separate monovalent type 2 vaccine (mOPV2) was to be used only to target existing cVDPV2 outbreaks. Further, a novel oral vaccine targeting type 2 (nOPV2) that has been genetically stabilized to make it less prone to give rise to circulating vaccine-derived strains is now in limited use.[32][21] Eradication efforts will eventually require all oral vaccination to be discontinued in favor of the use of injectable vaccines. These vaccines are more expensive and more difficult to deliver, and they lack the ability to induce contact immunity because they contain only killed virus, but they likewise are incapable of giving rise to vaccine-derived viral strains.[33][34]

Surveillance

A global program of surveillance for the presence of polio and the poliovirus plays a critical role in assessment of eradication and in outbreak detection and response. Two distinct methods are used in tandem: acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance and environmental surveillance.[35]

Monitoring for AFP aims at identifying outbreaks of polio by screening patients displaying symptoms consistent with, but not exclusive to, severe poliovirus infection. Stool samples are collected from children presenting with AFP and evaluated for the presence of poliovirus by accredited laboratories in the Global Polio Laboratory Network. Since rates of non-polio AFP are expected to be constant and large compared to the number of polio cases, the frequency of non-polio AFP reported in a population is indicative of the effectiveness of surveillance, as is the proportion of AFP patients from whom high-quality stool samples are collected and tested, with a target of at least 80%.[35]

Environmental surveillance is used to supplement AFP surveillance. This entails the routine testing of sewage samples for the presence of virus, which not only allows the effectiveness of vaccination efforts to be evaluated in countries with active transmission, but also allows the detection of new outbreaks in countries without known transmission. In 2018, the GPEI conducted environmental surveillance in 44 countries, 24 of which are in Africa.[35]

Obstacles

Among the greatest obstacles to global polio eradication are the lack of basic health infrastructure, which limits vaccine distribution and delivery, the crippling effects of civil war and internal strife, and the sometimes oppositional stance that marginalized communities take against what is perceived as a potentially hostile intervention by outsiders. Another challenge has been maintaining the potency of live (attenuated) vaccines in extremely hot or remote areas. The oral polio vaccine must be kept at 2 to 8 °C (36 to 46 °F) for vaccination to be successful.[17]

An independent evaluation of obstacles to polio eradication requested by the WHO and conducted in 2009 considered the major obstacles in detail by country. In Afghanistan and Pakistan, the researchers concluded that the most significant barrier was insecurity, but that managing human resources, political pressures, the movement of large populations between and within both countries, and inadequately resourced health facilities also posed problems, as did technical issues with the vaccine. In India, the major challenge appeared to be the high efficiency of transmission within the populations of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh states, set against the low (~80% after three doses against type 1) seroconversion response seen from the vaccine. In Nigeria, the most critical barriers identified were management issues, in particular the highly variable importance ascribed to polio by different authorities at the local government level, although funding issues, community perceptions of vaccine safety, inadequate mobilisation of community groups, and issues with the cold chain also played a role. In those countries where international spread from endemic countries had resulted in the reestablishment of transmission, namely Angola, Chad, and South Sudan, the key issues identified were underdeveloped health systems and low routine vaccine coverage, although the low level of resources committed to Angola and South Sudan for the purpose of curtailing the spread of polio and climatic factors was also identified as playing a role.[36]

Two additional challenges are found in unobserved polio transmission and in vaccine-derived poliovirus. First, most individuals infected with poliovirus are asymptomatic or exhibit minor symptoms, with fewer than 1% of infections leading to paralysis,[37] and most infected people are unaware that they carry the disease, allowing polio to spread widely before cases are seen.[38] In 2000, using new screening techniques for the molecular characterization of outbreak viral strains, it was discovered that some of the outbreaks were actually caused by circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus, following mutations or recombinations in the attenuated strain used for the oral polio vaccine. This discovery altered the strategy for the discontinuation of vaccination following polio eradication,[39] necessitating an eventual switch to the more expensive and logistically more problematic inactivated polio vaccine, as continued use of the oral inactivated virus would continue to produce such revertant infection-causing strains.[40] The risk of vaccine-derived polio will persist long after the switch to inactivated vaccine, as a small number of chronic excretors continue to produce active virus for years (or even decades) after their initial exposure to the oral vaccine.[41]

In a 2012 interview with Pakistani newspaper Dawn, Dr. Hussain A. Gezari, the WHO's special envoy on global polio eradication and primary healthcare, gave his views on obstacles to eradication. He said that the biggest hurdle preventing Pakistan from becoming polio-free was holding district health officials properly accountable—in national eradication campaigns officials had hired their own relatives, even young children. Gezari asked, "How do you expect a seven-year-old thumb-sucking kid to implement a polio campaign of the government?" and added that, in spite of this, "the first national campaign was initiated by your government in 1994 and that year Pakistan reported 25,000 polio cases, and the number was just 198 last year, which clearly shows that the programme is working."[42]

Opposition to vaccination efforts

One factor contributing to the continued circulation of polio immunization programs has been opposition in some countries.[43]

In the context of the United States invasion of Afghanistan and the subsequent 2003 invasion of Iraq, rumours arose in the Muslim world that immunization campaigns were using intentionally-contaminated vaccines to sterilize local Muslim populations or to infect them with HIV. In Nigeria these rumours fit in with a longstanding suspicion of modern biomedicine, which since its introduction during the era of colonialism has been viewed as a projection of the power of western nations. Refusal of vaccination came to be viewed as resistance to western expansionism, and when the contamination rumours led the Nigerian Supreme Council for Sharia to call for a region-wide boycott of polio vaccination, polio cases in the country increased more than five-fold between 2002 and 2006, with the uncontrolled virus then spreading across Africa and globally.[44][45] In Afghanistan and Pakistan, fears that the vaccine contained contraceptives were one reason given by the Taliban in issuing fatwas against polio vaccination.[45][43][46] Skepticism in the Muslim world was exacerbated when it was learned in 2011 that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had conducted a fake hepatitis B immunization campaign to collect blood samples from Osama bin Laden's Abbottabad compound in order to confirm the genetic identity of the children living there, and by implication his own presence, leading directly to his killing.[47][48] In a letter written to CIA director Leon Panetta, the InterAction Alliance, a union of about 200 U.S.-based non-government organizations, deplored the actions of the CIA in using a vaccination campaign as a cover.[49] Pakistan reported the world's highest number of polio cases (198)[42][50] in 2011.[51] Religious boycotts based on contamination concerns have not been limited to the Muslim world. In 2015, after claiming that a tetanus vaccine contained a contraceptive, a group of Kenyan Catholic bishops called on their followers to boycott a planned round of polio vaccination. This did not have a major effect on vaccination rates, and dialog along with vaccine testing forestalled further boycott calls.[45]

Other religion-inspired refusals arise from concerns over whether the virus contains pig-derived products, and hence are haram (forbidden) in Islam,[52] prohibitions against taking of animal life that may be required for vaccine production,[45] or a resistance to interfering with disease processes perceived to be divinely-directed.[44][45] Concerns were addressed through extensive outreach, directed both toward the communities involved and respected clerical bodies, as well as promoting local ownership of the eradication campaign in each region. In early 2012, some parents refused to get their children vaccinated in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) but religious refusals in the rest of the country had "decreased manifold".[42] Even with the express support of political leaders, polio workers or their accompanying security guards have been kidnapped, beaten, or assassinated.[43]

Polio vaccination efforts have also faced resistance in another form. The priority placed on vaccination by national authorities has turned it into a bargaining chip, with communities and interest groups resisting vaccination, not due to direct opposition, but to leverage other concessions from governmental authorities. In Nigeria this has taken the form of 'block rejection' of vaccination that is only resolved when state officials agree to repair or improve schools and health-care facilities, pave roads or install electricity.[53] There have been several instances of threatened boycotts by health workers in Pakistan over payment disputes.[54][55] Some governments have been accused of withholding vaccination or the necessary accompanying infrastructure from regions where opposition to their rule is high.[56]

Polio eradication criteria

A country is regarded as polio free or non-endemic if no cases have been detected for a year.[57][58] However, it is still possible polio circulates under these circumstances, as was the case for Nigeria, where a particular strain of virus resurfaced after five years in 2016.[59] This can be due to chance, limited surveillance and under-vaccinated populations.[60] Moreover, for WPV1—the only type of the virus which is currently circulating following the eradication of WPV2 and WPV3—only 1 in 200 infection cases exhibit symptoms of polio paralysis in non-vaccinated children, and possibly even fewer in vaccinated children.[61] Therefore, even a single case is considered an epidemic.[62] According to modeling, it can take four to six months of no reported cases to achieve only a 50% chance of eradication, and one to two years for e.g. 95% chance.[60][61] Sensitivity of monitoring for circulation can be improved by sampling sewage. In Pakistan in the last couple of years, the number of paralysis cases has dropped relatively faster than the positive environmental samples, which has shown no progress since 2015. The presence of multiple infections with the same strain in the upstream area may not be detectable, so there are some saturation effects when monitoring the number of positive environmental samples.[63][64][65] Furthermore, virus may shed beyond the expected duration of several weeks in certain individuals. Contagiousness can not be readily excluded.[66] For a polio virus to be certified as eradicated worldwide, at least three years of good surveillance without cases needs to be achieved,[67] though this period may need to be longer for a strain like WPV3, where a lower proportion of those infected demonstrate symptoms, or if virus-positive environmental samples continue to be reported.[68] Wild poliovirus type 2 was certified eradicated in 2015, the last case having been detected in 1999.[69] Wild poliovirus type 3 has not been detected since 2012, and was certified eradicated in 2019.[70]

Timeline

| International wild poliovirus cases by year | ||

| Year | Estimated | Recorded |

|---|---|---|

| 1975 | — | 49,293[17] |

| ... | ||

| 1980 | 400,000[71] | 52,552[17] |

| ... | ||

| 1985 | — | 38,637[17] |

| ... | ||

| 1988 | 350,000[72] | 35,251[17] |

| ... | ||

| 1990 | — | 23,484[17] |

| ... | ||

| 1993 | 100,000[71] | 10,487[17] |

| ... | ||

| 1995 | — | 7,035[17] |

| ... | ||

| 2000 | — | 719[73] |

| ... | ||

| 2005 | — | 1,979[73] |

| ... | ||

| 2010 | — | 1,352[73] |

| 2011 | — | 650[73] |

| 2012 | — | 223[73] |

| 2013 | — | 416[73] |

| 2014 | — | 359[73] |

| 2015 | — | 74[73] |

| 2016 | — | 37[73] |

| 2017 | — | 22[74] |

| 2018 | — | 33[75] |

| 2019 | — | 176[75] |

| 2020 | — | 140[76] |

| 2021 | — | 5[77] |

Pre-1988

Following the widespread use of poliovirus vaccine in the mid-1950s, the incidence of poliomyelitis declined rapidly in many industrialized countries.[30] Czechoslovakia became the first country in the world to scientifically demonstrate nationwide eradication of poliomyelitis in 1960.[78] In 1962—just one year after Sabin's oral polio vaccine (OPV) was licensed in most industrialized countries—Cuba began using the oral vaccine in a series of nationwide polio campaigns. The early success of these mass vaccination campaigns suggested that polioviruses could be globally eradicated.[79] The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), under the leadership of Ciro de Quadros, launched an initiative to eradicate polio from the Americas in 1985.[80]

Much of the work towards eradication was documented by Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, as a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, in the book The End of Polio: Global Effort to End a Disease.[81]

1988–2000

In 1988, the World Health Organization (WHO), together with Rotary International, UNICEF, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) passed the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), with the goal of eradicating polio by the year 2000. The initiative was inspired by Rotary International's 1985 pledge to raise $120 million toward immunising all of the world's children against the disease.[80] The last case of wild poliovirus poliomyelitis in the Americas was reported in Peru, August 1991.[80]

On 20 August 1994. the Americas were certified as polio-free.[82] This achievement was a milestone in efforts to eradicate the disease.

In 1994, the Indian Government launched the Pulse Polio Campaign to eliminate polio. The current campaign involves annual vaccination of all children under age five.[83]

In 1995 Operation MECACAR (Mediterranean, Caucasus, Central Asian Republics and Russia) was launched; National Immunization Days were coordinated in 19 European and Mediterranean countries.[84] In 1998, Melik Minas of Turkey became the last case of polio reported in Europe.[85] In 1997, Mum Chanty of Cambodia became the last person to contract polio in the Indo-West Pacific region.[86] In 2000, the Western Pacific Region (including China) was certified polio-free.[86]

In October 1999, the last isolation of type 2 poliovirus occurred in India. This type of poliovirus was declared eradicated.[30][69]

Also in October 1999, The CORE Group—with funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)—launched its effort to support national eradication efforts at the grassroots level. The CORE Group commenced this initiative in Bangladesh, India and Nepal in South Asia, and in Angola, Ethiopia and Uganda in Africa.[87]

2001–2005

|

no data

<0.3

0.3–0.75

0.75–1.2

1.2–1.65

1.65–2.1

2.1–2.55

|

2.55–3

3–4

4–5

5–7.5

7.5–10

>10

|

By 2001, 575 million children (almost one-tenth the world's population) had received some two billion doses of oral polio vaccine.[88] The World Health Organization announced that Europe was polio-free on 21 June 2002, in the Copenhagen Glyptotek.[89]

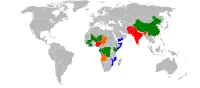

In 2002, an outbreak of polio occurred in India. The number of planned polio vaccination campaigns had recently been reduced, and populations in northern India, particularly from the Islamic background, engaged in mass resistance to immunization. At this time, the Indian state Uttar Pradesh accounted for nearly two-thirds of total worldwide cases reported.[90] (See the 2002 Global polio incidence map.) However, by 2004, India had adopted strategies to increase ownership of polio vaccinations in marginalized populations, and the immunity gap in vulnerable groups rapidly closed.

In August 2003, rumors spread in some states in Nigeria, especially Kano, that the vaccine caused sterility in girls. This resulted in the suspension of immunization efforts in the state, causing a dramatic rise in polio rates in the already endemic country.[91] On 30 June 2004, the WHO announced that after a 10-month ban on polio vaccinations, Kano had pledged to restart the campaign in early July. During the ban the virus spread across Nigeria and into 12 neighboring countries that had previously been polio-free.[80] By 2006, this ban would be blamed for 1,500 children being paralyzed and had cost $450 million for emergency activities. In addition to the rumors of sterility and the ban by Nigeria's Kano state, civil war and internal strife in Sudan and Côte d'Ivoire have complicated WHO's polio eradication goal. In 2004, almost two-thirds of all the polio cases in the world occurred in Nigeria (760 out of 1,170 total).

In May 2004 the first case of the polio outbreak in Sudan was detected. The reemergence of polio led to stepped up vaccination campaigns. In the city of Darfur, 78,654 children were immunized and 20,432 more in southern Sudan (Yirol and Chelkou).[92]

In 2005 there were 1,979 cases of wild poliovirus (excludes vaccine-derived polio viruses).[93] Most cases were located in two areas: the Indian subcontinent and Nigeria. Eradication efforts in the Indian sub-continent met with a large measure of success. Using the Pulse Polio campaign to increase polio immunization rates, India recorded just 66 cases in 2005, down from 135 cases reported in 2004, 225 in 2003, and 1,600 in 2002.[94]

Yemen, Indonesia, and Sudan, countries that had been declared polio-free since before 2000, each reported hundreds of cases—probably imported from Nigeria.[95] On 5 May 2005, news reports broke that a new case of polio was diagnosed in Java, Indonesia, and the virus strain was suspected to be the same as the one that has caused outbreaks in Nigeria. New public fears over vaccine safety, which were unfounded, impeded vaccination efforts in Indonesia. In summer 2005, the WHO, UNICEF and the Indonesian government made new efforts to lay the fears to rest, recruiting celebrities and religious leaders in a publicity campaign to promote vaccination.[96]

In the United States on 29 September 2005, the Minnesota Department of Health identified the first occurrence of vaccine derived polio virus (VDPV) transmission in the United States since OPV was discontinued in 2000. The poliovirus type 1 infection occurred in an unvaccinated, immunocompromised infant girl aged seven months (the index patient) in an Amish community whose members predominantly were not vaccinated for polio.[97]

2006–2010

In 2006, only four countries in the world (Nigeria, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan) were reported to have endemic polio. Cases in other countries are attributed to importation. A total of 1,997 cases worldwide were reported in 2006; of these the majority (1,869 cases) occurred in countries with endemic polio.[93] Nigeria accounted for the majority of cases (1,122 cases) but India reported more than ten times more cases this year than in 2005 (676 cases, or 30% of worldwide cases). Pakistan and Afghanistan reported 40 and 31 cases respectively in 2006. Polio re-surfaced in Bangladesh after nearly six years of absence with 18 new cases reported. "Our country is not safe, as neighbours India and Pakistan are not polio free", declared Health Minister ASM Matiur Rahman.[98] (See: Map of reported polio cases in 2006)

In 2007, there were 1,315 cases of poliomyelitis reported worldwide.[93] Over 60% of cases (874) occurred in India; while in Nigeria, the number of polio cases fell dramatically, from 1,122 cases reported in 2006 to 285 cases in 2007. Officials credit the drop in new infections to improved political control in the southern states and resumed immunisation in the north, where Muslim clerics led a boycott of vaccination in late 2003. Local governments and clerics allowed vaccinations to resume on the condition that the vaccines be manufactured in Indonesia, a majority Muslim country, and not in the United States.[95] Turai Yar'Adua, wife of recently elected Nigerian president Umaru Yar'Adua, made the eradication of polio one of her priorities. Attending the launch of immunization campaigns in Birnin Kebbi in July 2007, Turai Yar'Adua urged parents to vaccinate their children and stressed the safety of oral polio vaccine.[99]

In July 2007, a student traveling from Pakistan imported the first polio case to Australia in over 20 years.[100] Other countries with significant numbers of wild polio virus cases include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which reported 41 cases, Chad with 22 cases, and Niger and Myanmar, each of which reported 11 cases.[93]

In 2008, 19 countries reported cases and the total number of cases was 1,652. Of these, 1,506 occurred in the four endemic countries and 146 elsewhere. The largest number were in Nigeria (799 cases) and India (559 cases): these two countries contributed 82.2 percent of all cases. Outside endemic countries Chad reported the greatest number (37 cases).[93]

In 2009, a total of 1,606 cases were reported in 23 countries. Four endemic countries accounted for 1,256 of these, with the remaining 350 in 19 sub-Saharan countries with imported cases or re-established transmission. Once again, the largest number were in India (741) and Nigeria (388).[93] All other countries had less than one hundred cases: Pakistan had 89 cases, Afghanistan 38, Chad 65, Sudan 45, Guinea 42, Angola 29, Côte d'Ivoire 26, Benin 20, Kenya 19, Niger 15, Central African Republic 14, Mauritania 13 and Sierra Leone and Liberia both had 11. The following countries had single digit numbers of cases: Burundi 2, Cameroon 3, the Democratic Republic of the Congo 3, Mali 2, Togo 6 and Uganda 8.

According to figures updated in April 2012, the WHO reported that there were 1,352 cases of wild polio in 20 countries in 2010. Reported cases of polio were down 95% in Nigeria (to a historic low of 21 cases) and 94% in India (to a historic low of 42 cases) compared to the previous year, with little change in Afghanistan (from 38 to 25 cases) and an increase in cases in Pakistan (from 89 to 144 cases). An acute outbreak in Tajikistan gave rise to 460 cases (34% of the global total), and was associated with a further 18 cases across Central Asia (Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan) and the Russian Federation, with the most recent case from this region being reported from Russia 25 September. These were the first cases in the WHO European region since 2002. The Republic of Congo (Brazzaville) saw an outbreak with 441 cases (30% of the global total). At least 179 deaths were associated with this outbreak, which is believed to have been an importation from the ongoing type 1 outbreak in Angola (33 cases in 2010) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (100 cases).[93][101]

2011–2015

In 2011, 650 WPV cases were reported in sixteen countries: the four endemic countries—Pakistan, Afghanistan, Nigeria and India—as well as twelve others. Polio transmission recurred in Angola, Chad and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Kenya reported its first case since 2009, while China reported 21 cases, mostly among the Uyghurs of Hotan prefecture, Xinjiang, the first cases since 1994.

The total number of wild-virus cases reported in 2012 was 223, lower than any previous year. These were limited to five countries—Nigeria, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Chad, and Niger—of which all except Nigeria had fewer cases than in 2011.[102] Several additional countries, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia and Yemen, saw outbreaks of circulating vaccine-derived polio. The last reported type 3 case of polio worldwide had its onset 11 November 2012 in Nigeria; the last wild case outside Nigeria was in April 2012 in Pakistan,[102] and its absence from sewage monitoring in Pakistan suggests that active transmission of this strain has ceased there.[103] A total of 416 wild-virus cases were reported in 2013, almost double the previous year. Of these, cases in endemic countries dropped from 197 to 160, while those in non-endemic countries jumped from 5 to 256 owing to two outbreaks: one in the Horn of Africa, and one in Syria.

In April, a case of wild polio in Mogadishu was reported, the first in Somalia since 2007.[104] By October, over 170 cases had been reported in the country,[105] with more cases in neighboring Kenya and the Somali Region of Ethiopia.

Routine sewage monitoring in 2012 had detected a WPV1 strain of Pakistani origin in Cairo, sparking a major vaccination push there.[106] The strain spread to Israel, where there was widespread environmental detection, but like Egypt, no paralysis cases.[107][108][109] It had more severe consequences when it spread to neighboring Syria, with the total number of cases eventually reaching 35, the first outbreak there since 1999.[110][111]

In April 2013, the WHO announced a new $5.5 billion, 6-year cooperative plan (called the 2013–18 Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic Plan) to eradicate polio from its last reservoirs. The plan called for mass immunization campaigns in the three remaining endemic countries, and also dictated a switch to inactivated virus injections, to avoid the risk of the vaccine-derived outbreaks that occasionally occur from use of the live-virus oral vaccine.[112]

In 2014, there were 359 reported cases of wild poliomyelitis, spread over twelve countries. Pakistan had the most with 306, an increase from 93 in 2013, which was blamed on Al Qaeda and Taliban militants preventing aid workers from vaccinating children in rural regions of the country.[113][114] On 27 March 2014, the WHO announced the eradication of poliomyelitis in the South-East Asia Region, in which the WHO includes eleven countries: Bangladesh, Bhutan, North Korea, India, Indonesia, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Timor-Leste.[115] With the addition of this region, the proportion of world population living in polio-free regions reached 80%.[115] The last case of wild polio in the South-East Asia Region was reported in India on 13 January 2011.[116]

During 2015, 74 cases of wild poliomyelitis were reported worldwide, 54 in Pakistan and 20 in Afghanistan. There were 32 circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) cases in 2015.[117][118]

On 25 September 2015, the WHO declared that Nigeria was no longer considered endemic for wild polio virus,[57] with no reported case of wild polio virus having been reported since 24 July 2014.[102] A WPV1 strain not seen in five years resurfaced in Nigeria the following year.[59]

The WPV2 virus was declared eradicated in September 2015 as it had not been detected in circulation since 1999[69] and WPV3 was declared eradicated in October 2019,[7] having last been detected in 2012. Both types persist in the form of circulating vaccine-derived strains, the product of years-long evolution of transmissible oral vaccine in under-immunized populations.[119]

2016

Reported polio cases in 2016[120]

| ||||

| Country | Wild cases | Circulating vaccine- derived cases | Transmission status | Type(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | 20 | 1 | endemic | WPV1 cVDPV2 |

| Afghanistan | 13 | 0 | endemic | WPV1 |

| Nigeria | 4 | 1 | endemic | WPV1 cVDPV2 |

| Laos | 0 | 3 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 |

| Total | 37 | 5 | ||

There were 37 reported WPV1 cases with an onset of paralysis in 2016, half as many as in 2015, with the majority of the cases in Pakistan and Afghanistan.[121] A small number of additional cases in Nigeria, caused by WPV1, were viewed as a setback, the first being detected there in almost two years, yet the virus had been circulating undetected in regions inaccessible due to the activities of Boko Haram.[59][122] There was also a cVDPV1 outbreak in Laos,[123] while new strains of cVDPV2 arose separately in Nigeria's Borno and Sekoto states, and in the Quetta area of Pakistan,[124][125] collectively causing five cases.

Because cVDPV2 strains continued to arise from trivalent oral vaccine that included attenuated PV2, this vaccine was replaced with a bivalent version lacking WPV2 as well as trivalent injected inactivated vaccine that cannot lead to cVDPV cases. This was expected to prevent new strains of cVDPV2 from arising and allow eventual cessation of WPV2 vaccination.[126] The resulting global use of the injectable vaccine caused shortages, and a protocol using vaccine at one fifth the normal dose (fractional-Dose Inactivated Polio Vaccine, or fIPV) was introduced.[23]

2017

Reported polio cases in 2017[120]

| ||||

| Country | Wild cases | Circulating vaccine- derived cases | Transmission status | Type(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 14 | 0 | endemic | WPV1 |

| Pakistan | 8 | 0 | endemic | WPV1 |

| Dem. Rep. Congo | 0 | 22 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Syria | 0 | 74 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Total | 22 | 96 | ||

There were 22 reported WPV1 polio cases with onset of paralysis in 2017, down from 37 in 2016. Eight of the cases were in Pakistan and 14 in Afghanistan,[74] where genetic typing showed repeated introduction from Pakistan as well as local transmission.[127] In Pakistan, transmission of several genetic lineages of WPV1 seen in 2015 had been interrupted by September 2017, though at least two genetic clusters remain. In spite of a significant drop in detected cases in Pakistan, there was an increase in the percentage of environmental samples that test positive for the polio virus, suggesting gaps in identification of infected individuals.[128][129] In the third country where polio remains endemic, Nigeria, there were no cases, though as few as 7% of infants were fully vaccinated in some districts.[130][131] An April 2017 spill at a vaccine production facility in the Netherlands only resulted in one asymptomatic WPV2 infection, despite release into the sewer system.[132]

Laos was declared free of cVDPV1 in March,[58][133] but three distinct cVDPV2 outbreaks occurred in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, one of them of recent origin, the other two having circulated undetected for more than a year. Together they caused 20 cases by year's end.[134][135][136][137] In Syria a large outbreak began at Mayadin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate, a center of fighting in the Syrian Civil War and also spreading to neighboring districts saw 74 confirmed cases from a viral strain that had circulated undetected for about two years.[138][139] Circulation of multiple genetic lines of cVDPV2 was also detected in Banadir province, Somalia, but no infected individuals were identified.[140] WHO's Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization recommended that cVDPV2 suppression be prioritized over targeting WPV1,[141] and according to protocol OPV2 is restricted to this purpose.

The 2016 global switch in vaccination methods resulted in shortages of the injectable vaccine,[142] and led the WHO in April 2017 to recommend general use of the fIPV vaccination protocol, involving subcutaneous injection of a lower dose than used in the standard intramuscular delivery.[143]

2018

.jpg.webp)

| Country | Wild cases | Circulating vaccine- derived cases | Transmission status | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 21 | 0 | endemic | WPV1 |

| Pakistan | 12 | 0 | endemic | WPV1 |

| Nigeria | 0 | 34 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Papua New Guinea | 0 | 26 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 |

| Dem. Rep. Congo | 0 | 20 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Niger | 0 | 10 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Somalia | 0 | 6 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 cVDPV3 |

| Indonesia | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 |

| Mozambique | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Total | 33 | 98 | ||

There were 33 reported WPV1 paralysis cases with an onset of paralysis in 2018 – 21 in Afghanistan and 12 in Pakistan.[75][145] In Pakistan, three of the cases occurred in Kohlu District in Balochistan, with eight in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and one in the greater Karachi area, Sindh.[146] Viral circulation across much of the country, including several major urban areas, led to wild poliovirus detection in 20% of the year's environmental samples.[147] The rates of parental refusal for vaccination were increasing.[148] Polio in Pakistan resurged in the latter part of the year.[149] Cases in Afghanistan represented two transmission clusters, one in Kandahar, Urozgan and Helmand Provinces in the south, the other in the adjacent Nuristan, Kunar and Nangarhar Provinces in the northeast, on the Pakistani border.[150][151] Virus involved in several Afghanistan cases had a closest relative in Pakistan, suggesting significant trans-border spread, but the majority represented spread within Afghanistan. Some of these were caused by so-called 'orphan' strains, resulting from long undetected transmission and indicating gaps in monitoring. Different strains were largely responsible for the cases in the northwest and south of the country.[152] In Nigeria, the third country classified as having endemic transmission, security concerns continued to limit access to some areas of the country, though migration and novel vaccination approaches would reduce the number of unreached children.[131][153] The nation passed two full years without a detected wild-virus case, though elimination of WPV transmission could not be confirmed.[154]

Cases caused by vaccine-derived poliovirus were reported in seven countries, with almost 100 total cases. Surveillance detected nine strains of cVDPV in 2018 in seven countries.[35] In the Democratic Republic of Congo, one of the outbreaks of cVDPV2 first detected in 2017 caused no additional cases, but suppression of the other two with OPV2 proved insufficient: not only did they continue, but the vaccination efforts gave rise to a novel cVDPV2 outbreak.[137] The country experienced a total of 20 cases in 2018.[136][155] Two separate cVDPV2 outbreaks in northern Nigeria produced 34 cases,[155][156] as well as giving rise to 10 cases in the neighboring Niger. In Somalia, cVDPV2 continued to circulate, causing several polio cases and detected in environmental samples from as far as Nairobi, Kenya. This virus, along with newly detected cVDPV3, caused twelve total cases in the country, including one patient infected by both strains.[155][140][157] The large number of children residing in areas inaccessible to health workers represent a particular risk for undetected cVDPV outbreaks.[137] A cVDPV2 outbreak in Mozambique also resulted in a single case.[155][158] Response to the Syrian cVDPV2 outbreak continued into 2018, and virus transmission was successfully interrupted.[159] In Papua New Guinea, a cVDPV1 strain arose, causing twenty-six polio cases across nine provinces,[160] while a single diagnosed cVDPV1 case in neighboring Indonesia,[155] resulted from a distinct outbreak.

2019

| Country | Wild cases | Circulating vaccine- derived cases | Transmission status | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | 146 | 22 | endemic | WPV1 cVDPV2 |

| Afghanistan | 29 | 0 | endemic | WPV1 |

| Angola | 0 | 138 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Dem. Rep. Congo | 0 | 88 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Central African Rep. | 0 | 21 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Ghana | 0 | 18 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Nigeria | 0 | 18 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Ethiopia | 0 | 14 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Philippines | 0 | 14 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 cVDPV2 |

| Chad | 0 | 11 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Benin | 0 | 8 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Togo | 0 | 8 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Myanmar | 0 | 6 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 |

| Somalia | 0 | 3 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Malaysia | 0 | 3 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 |

| Zambia | 0 | 2 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Burkina Faso | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| China | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Niger | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Yemen | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 |

| Total | 176 | 378 | ||

There were 176 WPV1 paralysis cases detected in 2019: 29 in Afghanistan and 147 in Pakistan.[75][161] In particular, in Pakistan the number of cases was surging.[162][163] Transborder migration continued to play a role in polio transmission in the two countries.[164][165] While itself problematic, this also fostered a dangerous false-narrative in both nations, blaming the other for the presence and spread of polio in their own country.[166] Environmental sampling in Pakistan showed the virus' presence in eight urban areas, a setback officials attributed primarily to vaccine refusal.[167] Opponents to vaccination in Pakistan launched a series of attacks in April that left a vaccinator and two security men dead, while false rumors and hoax videos reporting vaccine toxicity also disrupted vaccination efforts there.[163][168] Wild poliovirus of Pakistani origin[169] also spread to Iran where it was detected in several environmental samples.[161] Overall, the eradication efforts in Pakistan and Afghanistan have been characterized as having become a "horror show", undermined by "public suspicion, political infighting, mismanagement and security problems".[149][170]

In the third remaining country in which polio was classified as endemic, Nigeria, wild poliovirus has not been detected since October 2016, and levels of AFP surveillance are sufficient, even in security-compromised regions, to suggest transmission of WPV may have been interrupted.[153] Global WPV3 eradication was certified in October 2019, the virus not having been seen since 2012.[70]

In addition to the WPV resurgence in Pakistan and Afghanistan, 2019 saw a resurgence of cVDPV, with 366 cases.[155] The majority of cases were caused by cVDPV2 strains that were able to arise or spread as a consequence of the withdrawal of the PV2 strain from the standard vaccination regimen. Previous cVDPV2 outbreaks in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Somalia continued into 2019 and spread to neighboring countries, while several countries experienced new outbreaks.[171] In addition to eighteen reported paralysis cases in Nigeria, the cVDPV2 outbreaks there spread to Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, Ghana, Niger and Togo, while the virus was also detected in environmental samples from Cameroon and Ivory Coast. Somalia's continuing outbreaks caused a half-dozen cases there and in neighboring Ethiopia, with a separate Ethiopia outbreak adding one case. The Democratic Republic of Congo had numerous new and continuing outbreaks, producing more than 80 cases, while multiple new cVDPV2 outbreaks in Angola and the Central African Republic resulted in more than a hundred cases.[172] Individual new outbreaks of cVDPV2 also caused more than a dozen paralysis cases each in Pakistan[155] and the Philippines,[173][174] while smaller outbreaks struck Chad, China and Zambia.[155] A separate cVDPV1 outbreak in the Philippines also caused cases in Malaysia, where cVDPV2 of Filipino origin was also detected in environmental samples, while additional cVDPV1 outbreaks caused six cases in Myanmar and one case in Yemen.[155]

2020

| Country | Wild cases | Circulating vaccine- derived cases | Transmission status | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | 84 | 135 | endemic | WPV1 cVDPV2 |

| Afghanistan | 56 | 308 | endemic | WPV1 cVDPV2 |

| Chad | 0 | 99 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Dem. Rep. Congo | 0 | 81 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Burkina Faso | 0 | 65 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Ivory Coast | 0 | 63 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Sudan | 0 | 58 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Mali | 0 | 52 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| South Sudan | 0 | 50 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Guinea | 0 | 44 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Ethiopia | 0 | 36 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Yemen | 0 | 31 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 |

| Somalia | 0 | 14 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Ghana | 0 | 12 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Niger | 0 | 10 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Sierra Leone | 0 | 10 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Togo | 0 | 9 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Nigeria | 0 | 8 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Cameroon | 0 | 7 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Central African Rep. | 0 | 4 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Angola | 0 | 3 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Benin | 0 | 3 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Rep. Congo | 0 | 2 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Madagascar | 0 | 2 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 |

| Malaysia | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 |

| Philippines | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Tajikistan | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Total | 140 | 1112 | ||

There were 140 WPV1 reported paralysis cases with onset in 2020, in Afghanistan and Pakistan.[76] There were 1078 reported cases caused by both continuing and novel outbreaks of cVDPV2 in twenty-four countries, 34 cases due to cVDPV1 in Yemen, two cVDPV1 cases in Madagascar and a single cVDPV1 case in Malaysia. cVDPV was also detected in several additional countries with no diagnosed polio case.[175] While in the past cVDPV outbreaks tended to remain localized, significant international spread of these strains is now being observed.[176]

In March the GPEI announced that it had a moral imperative to redeploy some of its anti-polio resources against the COVID-19 pandemic, and recognized that the pandemic would affect its efforts at eradicating polio.[177] They recommended that all mass vaccination efforts, both routine nationwide vaccination campaigns and cleanup vaccination targeted at outbreaks, be postponed for several months even though this risks severe detrimental effects on eradication efforts, finding themselves "caught between two terrible situations".[178] Pakistan announced the restart of their polio vaccination campaigns in July, after their COVID numbers dropped.[179] Subsequent statistical analysis indicated that the COVID pandemic would also result in decreases of more than 30% globally in both AFP and environmental surveillance.[180]

In June, Nigeria was removed from the list of countries with endemic wild poliovirus, leaving only Pakistan and Afghanistan.[181] Two months later, the Africa Regional Certification Commission, an independent body appointed by the World Health Organization, declared the African continent free of wild poliovirus.[4] This certification came after extensive assessments of the certifications of National Polio Certification Commissions (NCCs)[182] and confirmation that at least 95% of Africa's population had been immunised.[4] WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom called it a "great day... but not the end of polio,"[183] as there remain major continuing outbreaks of the vaccine derived poliovirus in West Africa and Ethiopia in addition to wild cases in Afghanistan and Pakistan.[176]

Two additional challenges were a conspiracy theory circulating on social media claiming that the polio vaccine contained coronavirus, and moves by President Donald Trump of the United States to cut funding for the World Health Organization.[184]

2021

| Country | Wild cases | Circulating vaccine- derived cases | Transmission status | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 4 | 43 | endemic | WPV1 cVDPV2 |

| Malawi | 1 | 0 | reintroduced | WPV1 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 8 | endemic | WPV1 cVDPV2 |

| Nigeria | 0 | 415 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Tajikistan | 0 | 32 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Dem. Rep. Congo | 0 | 28 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Senegal | 0 | 17 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Yemen | 0 | 13 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 cVDPV2 |

| Niger | 0 | 15 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Madagascar | 0 | 12 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 |

| Ethiopia | 0 | 10 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| South Sudan | 0 | 9 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Guinea | 0 | 6 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Sierra Leone | 0 | 5 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Benin | 0 | 3 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Cameroon | 0 | 3 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 0 | 3 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Liberia | 0 | 3 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Burkina Faso | 0 | 2 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Mozambique | 0 | 2 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Rep. Congo | 0 | 2 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Ukraine | 0 | 2 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Somalia | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Total | 6 | 638 | ||

In 2021, six cases caused by wild poliovirus were confirmed, one in Pakistan, four in Afghanistan, and one in Malawi,[185] all caused by WPV1. Pakistan's lone case dated from January, but the virus continued to be detected in environmental samples through December,[185] and was present in most provinces of the country during the year.[187] The case in Malawi, the country's first in almost three decades and the first in Africa in five years, was seen as a significant setback to the eradication effort.[188][189][190] Based on similarity to a strain last detected in Pakistan in 2019, it is thought that WPV1 has been circulating undetected in the country for some time.[190]

Over 635 cases caused by cVDPV2 had been detected by year's end, over half being in Nigeria. Other countries with cVDPV2 cases include Afghanistan, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Congo, DRC, Ethiopia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mozambique, Niger, Pakistan, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Tajikistan, Ukraine and Yemen, with the virus found in environmental samples or in those from symptom-free humans in several additional African and Asian nations without reported cases.[186] An analysis of cVDPV2 strains from 2020 and the first half of 2021 attributed them to 38 distinct emergences, representing a mix of novel strains and previously-detected strains that continued to circulate, while several previously-circulating strains were no longer found.[191] For cVDPV1, 14 cases had been identified in Madagascar and Yemen. The only instance of cVDPV3 detected in the year was a single environmental sample from China in January.[186][191]

Despite previous resistance to eradication efforts, after their takeover of Afghanistan in 2021 the Taliban agreed to allow United Nations healthcare workers to carry out door-to-door vaccination nationwide for the first time in three years. They committed to allowing women to participate in the effort, and provided safety guarantees.[192]

March 2021 saw the first use of the modified nOPV2 vaccine in selected countries. This was engineered to allow vaccination against strain 2 poliovirus without the frequent spawning of cVDPV2 seen with the original OPV2. Full rollout was not expected until 2023.[21]

2022

| Country | Wild cases | Circulating vaccine- derived cases | Transmission status | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 1 | 0 | endemic | WPV1 |

| Dem. Rep. Congo | 0 | 3 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Nigeria | 0 | 3 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Madagascar | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV1 |

| Somalia | 0 | 1 | cVDPV only | cVDPV2 |

| Total | 1 | 8 | ||

As of 15 March, in 2022 one case of WPV1 polio had been recorded, in Afghanistan,[185] with one caused by cVDPV1 in Madagascar and seven by cVDPV2, one in Somalia and three each in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria.[186]

On 27 January 2022 Pakistan marked one year without a detected case of WPV1-caused polio, though the virus continued to appear in environmental samples from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region as recently as the previous month,[193][194][195] and polio cases due to cVDPV2 were seen during the period.[186]

See also

- Global Polio Eradication Initiative

- The Final Inch, a 2009 documentary film about the eradication effort

- List of diseases eliminated from the United States

- Mathematical modelling of infectious disease

- Polio in Pakistan

- Population health

- Transmission risks and rates

References

- ↑ "Polio Eradication". Global Health Strategies. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ "Smallpox [Fact Sheet]". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ↑ Ghosh P (14 October 2010). "Rinderpest virus has been wiped out, scientists say". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 Scherbel-Ball, Naomi (25 August 2020). "Africa declared free of polio". BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ↑ "Endemic Countries - GPEI". Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ↑ "Poliomyelitis (polio)". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- 1 2 "GPEI-Two out of three wild poliovirus strains eradicated". Archived from the original on 7 November 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- 1 2 Barrett S (2004). "Eradication versus control: the economics of global infectious disease policies" (PDF). Bull World Health Organ. 82 (9): 683–8. hdl:10665/269225. ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 2622975. PMID 15628206. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ↑ Cockburn TA (April 1961). "Eradication of infectious diseases". Science. 133 (3458): 1050–8. Bibcode:1961Sci...133.1050C. doi:10.1126/science.133.3458.1050. PMID 13694225.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (December 1993). "Recommendations of the International Task Force for Disease Eradication" (PDF). MMWR Recommendations and Reports. 42 (RR-16): 1–38. PMID 8145708. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (December 1999). "Global Disease Elimination and Eradication as Public Health Strategies. Proceedings of a conference. Atlanta, Georgia, USA. 23-25 February 1998" (PDF). MMWR Supplements. 48: 1–208. PMID 11186140. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ↑ Global Polio Eradication Initiative, World Health Organization (2003). Global polio eradication initiative: strategic plan 2004–2008 (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/42850. ISBN 978-92-4-159117-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ↑ "Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP)". Public Health Notifiable Disease Management Guidelines. Alberta Government Health and Wellness. 2018. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ↑ Global Polio Eradication Initiative, World Health Organization (April 2015). Polio environmental surveillance expansion plan: global expansion plan under the endgame strategy 2013-2018 (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/276245. WHO/POLIO/15.02. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "OPV". Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ↑ Paul J, Riordan J, Melnick J (1951). "Antibodies to three different antigenic types of poliomyelitis virus in sera from North Alaskan Eskimos". Am J Hyg. 54 (2): 275–85. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119485. PMID 14877808.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mastny L (25 January 1999). "Eradicating Polio: A Model for International Cooperation". Worldwatch Institute. Archived from the original on 8 June 2006. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ↑ Robertson, Susan. (1993) The Immunological Basis for Immunization Series. Module 6: Poliomyelitis. Archived 15 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland.

- 1 2 Nathanson N, Martin J (1979). "The epidemiology of poliomyelitis: enigmas surrounding its appearance, epidemicity, and disappearance". Am J Epidemiol. 110 (6): 672–92. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112848. PMID 400274.

- 1 2 3 "International travel and health: Poliomyelitis (Polio)". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Independent experts advise move to next use phase for novel oral polio vaccine type 2" (Press release). GPEI. 11 October 2021. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- 1 2 "IPV". Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- 1 2 Bahl S, Verma H, Bhatnagar P, Haldar P, Satapathy A, Kumar KN, Horton J, Estivariz CF, Anand A, Sutter R (August 2016). "Fractional-Dose Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine Immunization Campaign - Telangana State, India, June 2016" (PDF). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (33): 859–63. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a5. PMID 27559683. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ↑ Hiromasa Okayasu; Carolyn Sein; Diana Chang Blanc; Alejandro Ramirez Gonzalez; Darin Zehrung; Courtney Jarrahian; Grace Macklin; Roland W. Sutter (2017). "Intradermal Administration of Fractional Doses of Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine: A Dose-Sparing Option for Polio Immunization" (PDF). The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 216 (S1): S161–7. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix038. PMC 5853966. PMID 28838185. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ↑ Edward P K Parker; Natalie A Molodecky; Margarita Pons-Salort; Kathleen M O'Reilly; Nicholas C Grassly (2015). "Impact of inactivated poliovirus vaccine on mucosal immunity: implications for the polio eradication endgame". Expert Review of Vaccines. 14 (8): 1113–1123. doi:10.1586/14760584.2015.1052800. PMC 4673562. PMID 26159938.

- ↑ Branswell H (20 March 2014). "Combination of oral, injectable polio vaccine used for first time in outbreak". CTV. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 Fine P (1993). "Herd immunity: history, theory, practice" (PDF). Epidemiol Rev. 15 (2): 265–302. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036121. PMID 8174658. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ↑ Shaw L, Spears W, Billings L, Maxim P (October 2010). "Effective Vaccination Policies". Information Sciences. 180 (19): 3728–3744. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2010.06.005. ISSN 0020-0255. PMC 2967767. PMID 21057602.

- ↑ Minor PD, Bel EJ (1990). Picornaviridae (excluding Rhinovirus). In: Topley & Wilson's Principles of Bacteriology, Virology and Immunity (volume 4) (8th ed.). London: Arnold. pp. 324–357. ISBN 978-0-7131-4592-2. OCLC 32823271.

- 1 2 3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S (eds.). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (PDF) (13th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation. ISBN 978-0990449119. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ↑ Duintjer Tebbens R, Pallansch M, Kew O, Cáceres V, Sutter R, Thompson K (2005). "A dynamic model of poliomyelitis outbreaks: learning from the past to help inform the future". Am J Epidemiol. 162 (4): 358–72. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi206. PMID 16014773.

- ↑ "nOPV2". Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ "Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus". Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ Duintjer Tebbens, Duintjer Tebbens RJ, Thompson KM (September 2015). "Managing the risk of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus during the endgame: oral poliovirus vaccine needs". BMC Infectious Diseases. 15: 390. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1114-6. PMC 4582727. PMID 26404780.

- 1 2 3 4 Patel JC, Diop OM, Gardner T, Chavan S, Jorba J, Wassilak SG, Ahmed J, Snider CJ (April 2019). "Surveillance to Track Progress Toward Polio Eradication - Worldwide, 2017-2018" (PDF). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (13): 312–318. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6813a4. PMC 6611474. PMID 30946737. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ↑ "Polio Eradication Evaluation". Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ↑ "Poliomyelitis". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ↑ "Polio and Prevention". Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ↑ Pallansch MA (August 2018). "Ending Use of Oral Poliovirus Vaccine - A Difficult Move in the Polio Endgame". N. Engl. J. Med. 379 (9): 801–803. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1808903. PMC 8083018. PMID 30157390.

- ↑ Modlin JF (June 2010). "The bumpy road to polio eradication". N. Engl. J. Med. 362 (25): 2346–9. doi:10.1056/nejmp1005405. PMID 20573922.

- ↑ Diop OM, Burns CC, Sutter RW, Wassilak SG, Kew OM (June 2015). "Update on Vaccine-Derived Polioviruses - Worldwide, January 2014-March 2015" (PDF). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 64 (23): 640–6. PMC 4584736. PMID 26086635. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 Imran Ali Teepu (26 February 2012). "WHO rejects polio rumours". Dawn. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 Warraich HJ (June 2009). "Religious opposition to polio vaccination". Emerging Infect. Dis. 15 (6): 978a–978. doi:10.3201/eid1506.090087. PMC 2727330. PMID 19523311.

- 1 2 Ghani, Isaac; Willott, Chris; Dadari, Ibrahim; Larson, Heidi J. (2013). "Listening to the rumours: What the northern Nigeria polio vaccine boycott can tell us ten years on". Global Public Health. 8 (10): 1138–1150. doi:10.1080/17441692.2013.859720. PMC 4098042. PMID 24294986.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Njeru, Ian; Ajack, Yusuf; Muitherero, Charles; Onyango, Dickens; Musyoka, Johnny; Onuekusi, Iheoma; Kioko, Jackson; Muraguri, Nicholas; David, Robert (2016). "Did the call for boycott by the Catholic bishops affect the polio vaccination coverage in Kenya in 2015? A cross-sectional study". Pan African Medical Journal. 24: 120. doi:10.11604/pamj.2016.24.120.8986. PMC 5012825. PMID 27642458.

- ↑ Walsh D (14 February 2007). "Polio cases jump in Pakistan as clerics declare vaccination an American plot". The Guardian. Peshawar. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ Larson H (27 May 2012). "The CIA's fake vaccination drive has damaged the battle against polio". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ↑ "Bin Laden death: 'CIA doctor' accused of treason". BBC News Online. 6 October 2011. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ↑ Imran Ali Teepu (2 March 2012). "American NGOs assail CIA over fake polio drive". Dawn. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Guerin O (24 May 2012). "'Emergency plan' to eradicate polio launched". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Shah S (2 March 2012). "CIA tactics to trap Bin Laden linked with polio crisis, say aid groups". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Ahmed, Ali; Lee, Kah S.; Bukhsh, Allah; Al-Worafi, Yaser M.; Sarker, Moklesur; Ming, Long C.; Khan, Tahir M. (2018). "Outbreak of vaccine-preventable diseases in Muslim majority countries". Journal of Infection and Public Health. 11 (2): 153–155. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2017.09.007. PMID 28988775.

- ↑ Grossman S, Phillips J, Rosenzweig L (23 August 2016). "Polio is back in Nigeria, and the next vaccination campaign may have a surprising consequence". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 24 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ "Protesting health workers threaten to boycott anti-polio drive". Dawn. 5 September 2015. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ "Up in arms: EPI workers threaten to boycott polio drives in FATA". The Express Tribune. 26 April 2016. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ Sparrow A (20 February 2014). "Syria's Polio Epidemic: The Suppressed Truth". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- 1 2 "WHO Removes Nigeria from Polio-Endemic List". World Health Organization (WHO) (Press release). Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- 1 2 "The poliovirus transmission in Lao People's Democratic Republic has ceased" (Press release). World Health Organization (WHO). 6 March 2017. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Government of Nigeria reports 2 wild polio cases, first since July 2014". World Health Organization (WHO). Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- 1 2 McCarthy, Kevin A.; Chabot-Couture, Guillaume; Shuaib, Faisal (29 September 2016). "A spatial model of Wild Poliovirus Type 1 in Kano State, Nigeria: calibration and assessment of elimination probability". BMC Infectious Diseases. 16 (1): 521. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1817-3. ISSN 1471-2334. PMC 5041410. PMID 27681708.

- 1 2 Kalkowska DA, Duintjer Tebbens RJ, Pallansch MA, Cochi SL, Wassilak SG, Thompson KM (18 February 2015). "Modeling undetected live poliovirus circulation after apparent interruption of transmission: implications for surveillance and vaccination". BMC Infectious Diseases. 15: 66. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0791-5. ISSN 1471-2334. PMC 4344758. PMID 25886823.

- ↑ "Case 5: Eliminating Polio in Latin America and the Caribbean" (PDF). Center for Global Development (CGD). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 June 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ↑ "Surveillance Indicators". Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Archived from the original on 26 March 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ↑ Cowger TL, Burns CC, Sharif S, Gary HE, Iber J, Henderson E, Malik F, Zahoor Zaidi SS, Shaukat S, Rehman L, Pallansch MA, Orenstein WA (25 July 2017). "The role of supplementary environmental surveillance to complement acute flaccid paralysis surveillance for wild poliovirus in Pakistan - 2011-2013". PLOS ONE. 12 (7): e0180608. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1280608C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180608. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5526532. PMID 28742803.

- ↑ Roberts L (11 January 2018). "'What the hell is going on?' Polio cases are vanishing in Pakistan, yet the virus won't go away". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aas9789. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ↑ "This Man Has Been Shedding The Polio Virus For 28 Years". IFLScience. Archived from the original on 26 March 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ↑ Miles T (23 October 2015). "WHO experts signal victory over one of three polio strains". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ↑ Global Commission for the Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication (GCC) Report from the Sixteenth Meeting (PDF) (Report). Global Commission for the Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication. September 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Global Eradication Of Wild Poliovirus Type 2 Declared". Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Archived from the original on 12 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- 1 2 "Two out of three wild poliovirus strains eradicated". Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI). Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- 1 2 Lee, Jong Wook (1995). "Ending polio—now or never?". The Progress of Nations. Unicef. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- ↑ Aylward RB, Linkins J (April 2005). "Polio eradication: mobilizing and managing the human resources" (PDF). Bull. World Health Organ. 83 (4): 268–73. doi:10.1590/S0042-96862005000400010 (inactive 28 February 2022). hdl:10665/73115. PMC 2626205. PMID 15868017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2007.