Trachoma

| Trachoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Granular conjunctivitis, blinding trachoma, Egyptian ophthalmia[1] | |

| |

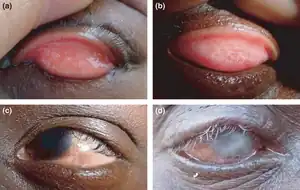

| (a) Active trachoma (b) Scarring of the inside of the eyelid (c) Eyelashes turned inwards (d) Resulting blindness | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Eye pain, blindness[2] |

| Causes | Chlamydia trachomatis spread between people[2] |

| Risk factors | Crowded living conditions, not enough clean water and toilets[2] |

| Prevention | Mass treatment, improved sanitation[3] |

| Treatment | Medications, surgery[2] |

| Medication | Azithromycin, tetracycline[3] |

| Frequency | 80 million[4] |

Trachoma is an infectious disease caused by bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis.[2] The infection causes a roughening of the inner surface of the eyelids.[2] This roughening can lead to pain in the eyes and breakdown of the outer surface or cornea of the eyes.[2] Untreated, repeated infections can result in permanent blindness, as the eyelids turn inward with altered eyelashes position, causing them to rub on the eye.[5]

The bacteria that cause the disease can be spread by both direct and indirect contact with an affected person's eyes or nose.[2] Indirect contact includes through clothing or flies that have come into contact with an affected person's eyes or nose.[2] Children spread the disease more often than adults.[2] Poor sanitation, crowded living conditions, and not enough clean water and toilets also increase spread.[2]

Efforts to prevent the disease include improving access to clean water and treatment with antibiotics to decrease the number of people infected with the bacterium.[2] This may include treating, all at once, whole groups of people in whom the disease is known to be common.[3] Washing, by itself, is not enough to prevent disease, but may be useful with other measures.[6] Treatment options include oral azithromycin and topical tetracycline.[3] Azithromycin is preferred because it can be used as a single oral dose.[7] After scarring of the eyelid has occurred, surgery may be required to correct the position of the eyelashes and prevent blindness.[2]

Globally, about 80 million people have an active infection.[4] In some areas, infections may be present in as many as 60–90% of children.[2] Among adults, it more commonly affects women than men – likely due to their closer contact with children.[2] The disease is the cause of decreased vision in 2.2 million people, of whom 1.2 million are completely blind.[2] It commonly occurs in 53 countries of Africa, Asia, and Central and South America, with about 230 million people at risk.[2] It results in US$8 billion of economic losses a year.[2] It belongs to a group of diseases known as neglected tropical diseases.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The bacterium has an incubation period of 6 to 12 days, after which the affected individual experiences symptoms of conjunctivitis, or irritation similar to "pink eye". Blinding endemic trachoma results from multiple episodes of reinfection that maintains the intense inflammation in the conjunctiva. Without reinfection, the inflammation gradually subsides.[8]

The conjunctival inflammation is called "active trachoma" and usually is seen in children, especially preschool children. It is characterized by white lumps in the undersurface of the upper eyelid (conjunctival follicles or lymphoid germinal centres) and by nonspecific inflammation and thickening often associated with papillae. Follicles may also appear at the junction of the cornea and the sclera (limbal follicles). Active trachoma often can be irritating and have a watery discharge. Bacterial secondary infection may occur and cause a purulent discharge.

The later structural changes of trachoma are referred to as "cicatricial trachoma". These include scarring in the eyelid (tarsal conjunctiva) that leads to distortion of the eyelid with buckling of the lid (tarsus) so the lashes rub on the eye (trichiasis). These lashes can lead to corneal opacities and scarring and then to blindness. Linear scar present in the sulcus subtarsalis is called Arlt's line (named after Carl Ferdinand von Arlt). In addition, blood vessels and scar tissue can invade the upper cornea (pannus). Resolved limbal follicles may leave small gaps in the pannus (Herbert's pits).

Most commonly, children with active trachoma do not present with any symptoms, as the low-grade irritation and ocular discharge is just accepted as normal, but further symptoms may include:

- Eye discharge

- Swollen eyelids

- Trichiasis (misdirected eyelashes)

- Swelling of lymph nodes in front of the ears

- Sensitivity to bright lights

- Increased heart rate

- Further ear, nose, and throat complications.

The major complication or the most important one is corneal ulcer occurring due to rubbing by concentrations, or trichiasis with superimposed bacterial infection.

Cause

Trachoma is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, serotypes (serovars) A, B, and C.[9] It is spread by direct contact with eye, nose, and throat secretions from affected individuals, or contact with fomites[10] (inanimate objects that carry infectious agents), such as towels and/or washcloths, that have had similar contact with these secretions. Flies can also be a route of mechanical transmission.[10] Untreated, repeated trachoma infections result in entropion (the inward turning of the eyelids), which may result in blindness due to damage to the cornea. Children are the most susceptible to infection due to their tendency to get dirty easily, but the blinding effects or more severe symptoms are often not felt until adulthood.

Blinding endemic trachoma occurs in areas with poor personal and family hygiene. Many factors are indirectly linked to the presence of trachoma including lack of water, absence of latrines or toilets, poverty in general, flies, close proximity to cattle, and crowding.[8][11] The final common pathway, though, seems to be the presence of dirty faces in children, facilitating the frequent exchange of infected ocular discharge from one child's face to another. Most transmission of trachoma occurs within the family.[8]

Diagnosis

McCallan's classification

McCallan in 1908 divided the clinical course of trachoma into four stages:

| Stage 1 (incipient trachoma) | Stage 2 (established trachoma) | Stage 3 (cicatrising trachoma) | Stage 4 (healed trachoma) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperaemia of palpebral conjunctiva | Appearance of mature follicle & papillae | Scarring of palpebral conjunctiva | Disease is cured or is not markable |

| Immature follicle | Progressive corneal pannus | Scars are easily visible as white bands | Sequelae to cicatrisation cause symptoms |

WHO classification

The World Health Organization recommends a simplified grading system for trachoma.[12] The Simplified WHO Grading System is summarized below:

Trachomatous inflammation, follicular (TF)—Five or more follicles of >0.5 mm on the upper tarsal conjunctiva

Trachomatous inflammation, intense (TI)—Papillary hypertrophy and inflammatory thickening of the upper tarsal conjunctiva obscuring more than half the deep tarsal vessels

Trachomatous scarring (TS)—Presence of scarring in tarsal conjunctiva.

Trachomatous trichiasis (TT)—At least one ingrown eyelash touching the globe, or evidence of epilation (eyelash removal)

Corneal opacity (CO)—Corneal opacity blurring part of the pupil margin

Prevention

Although trachoma was eliminated from much of the developed world in the 20th century (Australia being a notable exception), this disease persists in many parts of the developing world, particularly in communities without adequate access to water and sanitation.[13]

Environmental measures

Environmental improvement: Modifications in water use, fly control, latrine use, health education, and proximity to domesticated animals have all been proposed to reduce transmission of C. trachomatis. These changes pose numerous challenges for implementation. These environmental changes are likely to ultimately affect the transmission of ocular infection by means of lack of facial cleanliness.[8] Particular attention is required for environmental factors that limit clean faces.

A systematic review examining the effectiveness of environmental sanitary measures on the prevalence of active trachoma in endemic areas showed that use of insecticide spray resulted in significant reductions of trachoma and fly density in some studies.[14] Health education also resulted in reductions of active trachoma when implemented.[14] Improved water supply did not result in a reduction of trachoma incidence.[14]

Antibiotics

Antibiotic therapy: WHO Guidelines recommend that a region should receive community-based, mass antibiotic treatment when the prevalence of active trachoma among one- to nine-year-old children is greater than 10%.[15] Subsequent annual treatment should be administered for three years, at which time the prevalence should be reassessed. Annual treatment should continue until the prevalence drops below 5%. At lower prevalences, antibiotic treatment should be family-based.

Management

Antibiotics

Antibiotic selection: Azithromycin (single oral dose of 20 mg/kg) or topical tetracycline (1% eye ointment twice a day for six weeks). Azithromycin is preferred because it is used as a single oral dose. Although it is expensive, it is generally used as part of the international donation program organized by Pfizer.[7] Azithromycin can be used in children from the age of six months and in pregnancy.[8] As a community-based antibiotic treatment, some evidence suggests that oral azithromycin was more effective than topical tetracycline, but no consistent evidence supported either oral or topical antibiotics as being more effective.[3] Antibiotic treatment reduces the risk of active trachoma in individuals infected with chlamydial trachomatis.[3]

Surgery

Surgery: For individuals with trichiasis, a bilamellar tarsal rotation procedure is warranted to direct the lashes away from the globe.[16] Evidence suggests that use of a lid clamp and absorbable sutures would result in reduced lid contour abnormalities and granuloma formulation after surgery.[17] Early intervention is beneficial as the rate of recurrence is higher in more advanced disease.[18]

Lifestyle measures

The WHO-recommended SAFE strategy includes:

- Surgery to correct advanced stages of the disease

- Antibiotics to treat active infection, using azithromycin

- Facial cleanliness to reduce disease transmission

- Environmental change to increase access to clean water and improved sanitation

Children with visible nasal discharge, discharge from the eyes, or flies on their faces are at least twice as likely to have active trachoma as children with clean faces.[8] Intensive community-based health education programs to promote face-washing can reduce the rates of active trachoma, especially intense trachoma. If an individual is already infected, washing one's face is encouraged, especially a child, to prevent reinfection.[19] Some evidence shows that washing the face combined with topical tetracycline might be more effective in reducing severe trachoma compared to topical tetracycline alone.[6] The same trial found no statistical benefit of eye washing alone or in combination with tetracycline eye drops in reducing follicular trachoma amongst children.[6]

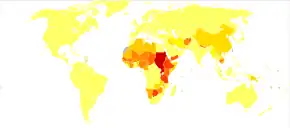

Prognosis

|

no data

≤10

10–20

20–40

40–60

60–80

80–100

|

100–200

200–300

300–400

400–500

500–600

≥600

|

If not treated properly with oral antibiotics, the symptoms may escalate and cause blindness, which is the result of ulceration and consequent scarring of the cornea. Surgery may also be necessary to fix eyelid deformities.

Without intervention, trachoma keeps families in a cycle of poverty, as the disease and its long-term effects are passed from one generation to the next.

Epidemiology

.png.webp)

As of 2011, about 21 million people are actively affected by trachoma, with around 2.2 million people being permanently blind or have severe visual impairment from trachoma. An additional 7.3 million people are reported to have trichiasis.[20] 51 countries are currently classified as endemic for blinding trachoma.[21] Of these, Africa is considered the worst affected area, with over 85% of all known active cases of trachoma.[21] Within the continent, South Sudan and Ethiopia have the highest prevalence.[21] In many of these communities, women are three times more likely than men to be blinded by the disease, due to their roles as caregivers in the family. Approximately 158 million people are living in areas were trachoma is common.[22] An additional 229 million live where trachoma could potentially occur.[21] Australia is the only developed country that has trachoma.[23] In 2008, trachoma was found in half of Australia's very remote communities.[23]

Elimination

In 1996, the WHO launched its Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020,[24] and in 2006, the WHO officially set 2020 as the target to eliminate trachoma as a public-health problem.[25] The International Coalition for Trachoma Control has produced maps and a strategic plan called 2020 INSight that lays out actions and milestones to achieve global elimination of blinding trachoma by 2020.[26] The program recommends the SAFE protocol for blindness prevention: Surgery for trichiasis, Antibiotics to clear infection, Facial cleanliness, and Environmental improvement to reduce transmission.[24] This includes sanitation infrastructure to reduce the open presence of human feces that can breed flies.[27]

As of 2018, Cambodia, Ghana, Iran, Laos, Mexico, Nepal, Morocco, and Oman have been certified as having eliminated trachoma as a public-health problem; China, Gambia, Iran, Iraq, and Myanmar make that claim, but have not sought certification.[27] Eradication of the bacterium that causes the disease is seen as impractical; the WHO definition of "eliminated as a public-health problem" means less than 5% of children have any symptoms, and less than 0.1% of adults have vision loss.[27] Having already donated more doses (about 700 million since 2002) of the drug than it has sold during the same time period, the drug company Pfizer has agreed to donate azithromycin until 2025, if necessary for elimination of the disease.[27] The campaign unexpectedly found distribution of azithromycin to very poor children reduced their early death rate by up to 25%.[27]

History

The disease is one of the earliest known eye afflictions, having been identified in Egypt as early as 15 BC.[8]

Its presence was also recorded in ancient China and Mesopotamia. Trachoma became a problem as people moved into crowded settlements or towns where hygiene was poor. It became a particular problem in Europe in the 19th century. After the Egyptian Campaign (1798–1802) and the Napoleonic Wars (1798–1815), trachoma was rampant in the army barracks of Europe and spread to those living in towns as troops returned home. Stringent control measures were introduced, and by the early 20th century, trachoma was essentially controlled in Europe, although cases were reported until the 1950s.[8] Today, most victims of trachoma live in underdeveloped and poverty-stricken countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control says, "No national or international surveillance [for trachoma] exists. Blindness due to trachoma has been eliminated from the United States. The last cases were found among Native American populations and in Appalachia, and those in the boxing, wrestling, and sawmill industries (prolonged exposure to combinations of sweat and sawdust often lead to the disease). In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, trachoma was the main reason for an immigrant coming through Ellis Island to be deported."[28][29]

In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson signed an act designating funds for the eradication of the disease.[30][31] Immigrants who attempted to enter the U.S. through Ellis Island, New York, had to be checked for trachoma.[28] During this time, treatment for the disease was by topical application of copper sulfate. By the late 1930s, a number of ophthalmologists reported success in treating trachoma with sulfonamide antibiotics.[32] In 1948, Vincent Tabone (who was later to become the President of Malta) was entrusted with the supervision of a campaign in Malta to treat trachoma using sulfonamide tablets and drops.[33]

Due to improved sanitation and overall living conditions, trachoma virtually disappeared from the industrialized world by the 1950s, though it continues to plague the developing world to this day. Epidemiological studies were conducted in 1956–63 by the Trachoma Control Pilot Project in India under the Indian Council for Medical Research.[34] This potentially blinding disease remains endemic in the poorest regions of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East and in some parts of Latin America and Australia. Currently, 8 million people are visually impaired as a result of trachoma, and 41 million suffer from active infection.

Of the 54 countries that the WHO cited as still having blinding trachoma occurring, Australia is the only developed country—Australian Aboriginal people who live in remote communities with inadequate sanitation are still blinded by this infectious eye disease.[35]

India' s Health and Family Welfare Minister JP Nadda declared India free of infective trachoma in 2017.[36]

Etymology

The term is derived from New Latin trāchōma, from Greek τράχωμα trākhōma, from τραχύς trākhus "rough".[37]

Economics

The economic burden of trachoma is huge, particularly with regard to covering treatment costs and productivity losses as a result of increased visual impairment, and in some cases, permanent blindness.[2] The global estimated cost of trachoma is reported between $US2.9 and 5.3 billion each year.[2] By including the cost for trichiasis treatment, the estimated overall cost for the disease increases to about $US 8 billion.[2]

References

- ↑ Swanner, Yann A. Meunier; with contributions from Michael Hole, Takudzwa Shumba & B.J. (2014). Tropical diseases : a practical guide for medical practitioners and students. Oxford: Oxford University Press, USA. p. 199. ISBN 9780199997909. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 "Blinding Trachoma Fact sheet N°382". World Health Organization. November 2013. Archived from the original on 14 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Evans, Jennifer R.; Solomon, Anthony W.; Kumar, Rahul; Perez, Ángela; Singh, Balendra P.; Srivastava, Rajat Mohan; Harding-Esch, Emma (26 September 2019). "Antibiotics for trachoma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD001860. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001860.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6760986. PMID 31554017.

- 1 2 3 Fenwick, A (March 2012). "The global burden of neglected tropical diseases". Public Health. 126 (3): 233–6. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2011.11.015. PMID 22325616.

- ↑ Vaz, Francis; Mehta, Nischcay; Hamilton, Robin D. (2020). "27. Ear, nose and throat and eye disease". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 917. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 Ejere, HO; Alhassan, MB; Rabiu, M (20 February 2015). "Face washing promotion for preventing active trachoma". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD003659. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003659.pub4. PMC 4441394. PMID 25697765.

- 1 2 Mariotti SP (November 2004). "New steps toward eliminating blinding trachoma". New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (19): 2004–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMe048205. PMID 15525727.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Taylor, Hugh (2008). Trachoma: A Blinding Scourge from the Bronze Age to the Twenty-first Century. Centre for Eye Research Australia. ISBN 978-0-9757695-9-1.

- ↑ Mackern-Oberti, J. P.; Motrich, R. N. D. O.; Breser, M. A. L.; Sánchez, L. R.; Cuffini, C.; Rivero, V. E. (2013). "Chlamydia trachomatis infection of the male genital tract: An update". Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 100 (1): 37–53. doi:10.1016/j.jri.2013.05.002. PMID 23870458.

- 1 2 Goldman, Lee (2011). Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. pp. e326-2. ISBN 978-1437727883.

- ↑ Wright HR, Turner A, Taylor HR (June 2008). "Trachoma". Lancet. 371 (9628): 1945–54. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60836-3. PMID 18539226. S2CID 208790087.

- ↑ Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, West SK, Taylor HR (1987). "A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 65 (4): 477–83. PMC 2491032. PMID 3500800.

- ↑ Stocks, Meredith E. (2014). "Effect of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene on the Prevention of Trachoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS Medicine. 11 (2): e1001605. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001605. PMC 3934994. PMID 24586120.

- 1 2 3 Rabiu M, Alhassan MB, Ejere HO, Evans JR (2012). "Environmental sanitary interventions for preventing active trachoma". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD004003. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004003.PUB4. PMC 4422499. PMID 22336798.

- ↑ Solomon, AW; Zondervan M; Kuper H; et al. (2006). "Trachoma control: a guide for programme managers" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 July 2008.

- ↑ Reacher M, Foster A, Huber J. "Trichiasis Surgery for Trachoma. The Bilamellar Tarsal Rotation Procedure." 1993; World Health Organization, Geneva: WHO/PBL/93.29.

- ↑ Burton M, Habtamu E, Ho D, Gower EW (2015). "Interventions for trachoma trichiasis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (11): CD004008. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004008.pub3. PMC 4661324. PMID 26568232.

- ↑ Burton MJ, Kinteh F, Jallow O, et al. (October 2005). "A randomised controlled trial of azithromycin following surgery for trachomatous trichiasis in the Gambia". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 89 (10): 1282–8. doi:10.1136/bjo.2004.062489. PMC 1772881. PMID 16170117.

- ↑ Prevention-Trachoma Archived 2009-05-15 at the Wayback Machine 18 July 2008 – 24 March 2009

- ↑ Taylor, Hugh R; Burton, Matthew J; Haddad, Danny; West, Sheila; Wright, Heathcote (December 2014). "Trachoma". The Lancet. 384 (9960): 2142–2152. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62182-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 25043452.

- 1 2 3 4 "Epidemiological situation". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ↑ "Trachoma". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- 1 2 "Eye health in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2008. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- 1 2 "Ghana eliminates trachoma, freeing millions from suffering and blindness". World Health Organization. 13 June 2018. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ↑ "WHO | Blinding trachoma: Progress towards global elimination by 2020". 10 April 2006. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ "Global strategy lays out concrete action plan to eliminate blinding trachoma by 2020". International Coalition for Trachoma Control. July 2011. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McNeil, Donald G. Jr. (16 July 2018). "Now in Sight: Success Against an Infection That Blinds". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- 1 2 Yew, E (June 1980). "Medical inspection of immigrants at Ellis Island, 1891–1924". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 56 (5): 488–510. PMC 1805119. PMID 6991041.

- ↑ Disease Listing, Trachoma, Technical Information | CDC Bacterial, Mycotic Diseases Archived 2006-04-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Allen SK, Semba RD (2002). "The trachoma menace in the United States, 1897–1960". Survey of Ophthalmology. 47 (5): 500–9. doi:10.1016/S0039-6257(02)00340-5. PMID 12431697.

- ↑ Leupp, Constance D. (August 1914). "Removing The Blinding Curse Of The Mountains: How Dr. McMullen, Of The Public Health Service Is Organizing The War Against Trachoma In The Appalachians". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XLIV (2): 426–430. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- ↑ Thygeson P (1939). "The Treatment of Trachoma with Sulfanilamide: A Report of 28 Cases". Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 37: 395–403. PMC 1315791. PMID 16693194.

- ↑ Ophthalmology in Malta, C. Savona Ventura, University of Malta, 2003 Archived 2007-07-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Gupta, UC and Preobragenski, W (1964), Trachoma in India—Endemicity and Epidemiological study, Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, Volume 12, issue 2, pages 39–49.

- ↑ Taylor, Hugh R. (2001). "Trachoma in Australia". Medical Journal of Australia. 175 (7): 371–372. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143622.x. PMID 11700815. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013.

- ↑ "India now free of infective trachoma, says JP Nadda". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ↑ "tra·cho·ma". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. TheFreeDictionary. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

External links

- Celia W. Dugger (31 March 2006), "Preventable Disease Blinds Poor in Third World" Archived 15 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times

- Photographs of trachoma patients

- Trachoma Atlas Archived 24 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- International Trachoma Initiative Archived 22 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |