Keratitis

| Keratitis | |

|---|---|

| |

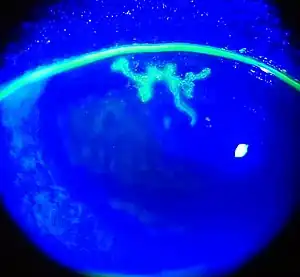

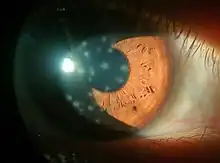

| An eye with non-ulcerative sterile keratitis. | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

Keratitis is a condition in which the eye's cornea, the clear dome on the front surface of the eye, becomes inflamed.[1] The condition is often marked by moderate to intense pain and usually involves any of the following symptoms: pain, impaired eyesight, photophobia (light sensitivity), red eye and a 'gritty' sensation.[2]

Classification (by chronicity)

Acute

- Acute epithelial keratitis

- Nummular keratitis

- Interstitial keratitis

- Disciform keratitis

Chronic

- Neurotrophic keratitis

- Mucous plaque keratitis

Classification (infective)

Viral

- Herpes simplex keratitis (dendritic keratitis). Viral infection of the cornea is often caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV) which frequently leaves what is called a 'dendritic ulcer'.

- Herpes zoster keratitis, associated with herpes zoster ophthalmicus, which is a form of shingles.

Bacterial

- Bacterial keratitis. Bacterial infection of the cornea can follow from an injury or from wearing contact lenses. The bacteria involved are Staphylococcus aureus and for contact lens wearers, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Pseudomonas aeruginosa contains enzymes that can digest the cornea.[3]

Fungal

- Fungal keratitis, caused by Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans (cf. Fusarium, causing an outbreak of keratitis in 2005–2006 through the possible vector of Bausch & Lomb ReNu with MoistureLoc contact lens solution[4])

Amoebic

- Amoebic infection of the cornea is a serious corneal infection, often affecting contact lens wearers.[5][6] It is usually caused by Acanthamoeba. On May 25, 2007, the U.S. Center for Disease Control issued a health advisory due to increased risk of Acanthamoeba keratitis associated with use of Advanced Medical Optics Complete Moisture Plus Multi-Purpose eye solution.[7]

Parasitic

- Onchocercal keratitis, which follows Onchocerca volvulus infection by infected blackfly bite. These blackfly, Simulium, usually dwell near fast-flowing African streams, so the disease is also called "river blindness".[8]

Classification (by stage of disease)

Classification (by environmental aetiology)

- Exposure keratitis (also known as exposure keratopathy) — due to dryness of the cornea caused by incomplete or inadequate eyelid closure (lagophthalmos).

- Photokeratitis — keratitis due to intense ultraviolet radiation exposure (e.g. snow blindness or welder's arc eye.)

- Contact lens acute red eye (CLARE) — a non-ulcerative sterile keratitis associated with colonization of Gram-negative bacteria on contact lenses.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the cause of the keratitis. Infectious keratitis can progress rapidly, and generally requires urgent antibacterial, antifungal, or antiviral therapy to eliminate the pathogen. Antibacterial solutions include levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin, ofloxacin. It is unclear if steroid eye drops are useful or not.[9]

In addition, contact lens wearers are typically advised to discontinue contact lens wear and replace contaminated contact lenses and contact lens cases. (Contaminated lenses and cases should not be discarded as cultures from these can be used to identify the pathogen).

Aciclovir is the mainstay of treatment for HSV keratitis and steroids should be avoided at all costs in this condition. Application of steroids to a dendritic ulcer caused by HSV will result in rapid and significant worsening of the ulcer to form an 'amoeboid' or 'geographic' ulcer, so named because of the ulcer's map like shape.[10]

Prognosis

Some infections may scar the cornea to limit vision. Others may result in perforation of the cornea, endophthalmitis (an infection inside the eye), or even loss of the eye. With proper medical attention, infections can usually be successfully treated without long-term visual loss.

In non-humans

- Feline eosinophilic keratitis — affecting cats and horses; possibly initiated by feline herpesvirus 1 or other viral infection.[11]

See also

- Chronic superficial keratitis, or pannus, for the disease in dogs

- Thygeson's superficial punctate keratopathy

- Keratoendotheliitis fugax hereditaria

References

- ↑ Singh, Prabhakar; Gupta, Abhishek; Tripathy, Koushik (2021), "Keratitis", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32644440, retrieved 2021-11-02

- ↑ "Ophthalmology & Visual Sciences". Chicago Medicine. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ↑ Tang A, Marquart ME, Fratkin JD, McCormick CC, Caballero AR, Gatlin HP, O'Callaghan RJ (2009). "Properties of PASP: A Pseudomonas Protease Capable of Mediating Corneal Erosions". Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 50 (8): 3794–801. doi:10.1167/iovs.08-3107. PMC 2874894. PMID 19255155.

- ↑ Epstein, Arthur B (December 2007). "In the aftermath of the Fusarium keratitis outbreak: What have we learned?". Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 1 (4): 355–366. ISSN 1177-5467. PMC 2704532. PMID 19668512.

- ↑ Lorenzo-Morales, Jacob; Khan, Naveed A.; Walochnik, Julia (2015). "An update on Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment". Parasite. 22: 10. doi:10.1051/parasite/2015010. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 4330640. PMID 25687209.

- ↑ Martín-Navarro, M.; Lorenzo-Morales, J.; Cabrera-Serra, G.; Rancel, F.; Coronado-Alvarez, M.; Piñero, E.; Valladares, B. (Nov 2008). "The potential pathogenicity of chlorhexidine-sensitive Acanthamoeba strains isolated from contact lens cases from asymptomatic individuals in Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 57 (Pt 11): 1399–1404. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.2008/003459-0. ISSN 0022-2615. PMID 18927419.

- ↑ CDC Advisory Archived 2007-05-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "What is onchocerciasis?". CDC. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

transmission is most intense in remote African rural agricultural villages, located near rapidly flowing streams...(WHO) expert committee on onchocerciasis estimates the global prevalence is 17.7 million, of whom about 270,000 are blind.

- ↑ Herretes, S; Wang, X; Reyes, JM (Oct 16, 2014). "Topical corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy for bacterial keratitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD005430. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005430.pub3. PMC 4269217. PMID 25321340.

- ↑ John F., Salmon (2020). "Cornea". Kanski's clinical ophthalmology : a systematic approach (9th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-7020-7713-5. OCLC 1131846767.

- ↑ "VET.uga.edu". Archived from the original on 2009-11-19. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

External links

- Facts About the Cornea and Corneal Disease The National Eye Institute (NEI)

- Filimentary keratitis