Health at Every Size

| Part of a series on |

| Human body weight |

|---|

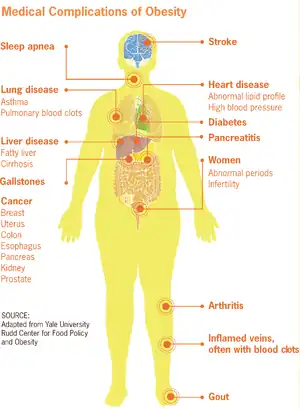

Health at Every Size (HAES) is an approach to public health that seeks to de-emphasise weight loss as a health goal, and reduce stigma towards people who are overweight or obese.[1] Proponents argue that traditional interventions focused on weight loss, such as dieting, do not reliably produce positive health outcomes, and that health is a result of lifestyle behaviors that can be performed independently of body weight.[2] Critics of the approach argue that weight loss should sometimes be an explicit goal of healthcare interventions, because of the negative health outcomes of obesity.[3]

History

Health at Every Size first appeared in the 1960s, advocating that the changing culture toward physical attractiveness and beauty standards had negative health and psychological repercussions to fat people. They believed that because the slim and fit body type had become the acceptable standard of attractiveness, fat people were going to great pains to lose weight, and that this was not, in fact, always healthy for the individual. They contend that some people are naturally a larger body type, and that in some cases losing a large amount of weight could in fact be extremely unhealthy for some. On November 4, 1967, Lew Louderback wrote an article called "More People Should Be Fat!" that appeared in a major national magazine, The Saturday Evening Post.[4] In the opinion piece, Louderback argued that:

- "Thin fat people" suffer physically and emotionally from having dieted to below their natural body weight.

- Forced changes in weight are not only likely to be temporary, but also to cause physical and emotional damage.

- Dieting seems to unleash destructive and emotional tendencies.

- Eating without dieting allowed Louderback and his wife to relax and feel better while maintaining the same weight.

Bill Fabrey, a young engineer at the time, read the article and contacted Louderback a few months later in 1968. Fabrey helped Louderback research his subsequent book, Fat Power, and Louderback supported Fabrey in founding the National Association to Aid Fat Americans (NAAFA) in 1969, a nonprofit human rights organization. NAAFA would subsequently change its name by the mid-1980s to the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance.

In the early 1980s, four books collectively put forward ideas related to Health At Every Size. In Diets Don't Work (1982), Bob Schwartz encouraged "intuitive eating",[5] as did Molly Groger in Eating Awareness Training (1986). Those authors believed this would result in weight loss as a side effect. William Bennett and Joel Gurin's The Dieter's Dilemma (1982), and Janet Polivy and C. Peter Herman's Breaking The Diet Habit (1983) argued that everybody has a natural weight and set-point, and that dieting for weight loss does not work.[6]

According to Lindo Bacon, in Health at Every Size (2008), the basic premise of HAES is that "well-being and healthy habits are more important than any number on the scale."[7] Emily Nagoski, in her book Come as You Are (2015), promoted the idea of Health at Every Size for improving women's self-confidence and sexual well-being.[8]

Principles

The Health At Every Size Principles are:[9]

- "Weight Inclusivity: Accept and respect the inherent diversity of body shapes and sizes and reject the idealizing or pathologizing of specific weights."

- "Health Enhancement: Support health policies that improve and equalize access to information and services, and personal practices that improve human well-being, including attention to individual physical, economic, social, spiritual, emotional, and other needs."

- "Respectful Care: Acknowledge our biases, and work to end weight discrimination, weight stigma, and weight bias. Provide information and services from an understanding that socio-economic status, race, gender, sexual orientation, age, and other identities impact weight stigma, and support environments that address these inequities."

- "Eating for Well-being: Promote flexible, individualized eating based on hunger, satiety, nutritional needs, and pleasure, rather than any externally regulated eating plan focused on weight control."

- "Life-Enhancing Movement: Support physical activities that allow people of all sizes, abilities, and interests to engage in enjoyable movement, to the degree that they choose.”

Science

Proponents claim that evidence from certain scientific studies has provided some rationale for a shift in focus in health management from weight loss to a weight-neutral approach in individuals who have a high risk of type 2 diabetes and/or symptoms of cardiovascular disease, and that a weight-inclusive approach focusing on health biomarkers, instead of weight-normative approaches focusing on weight loss alone, provides greater health improvements.[10][11]

There is strong evidence that being obese is associated with increased all-causes mortality, and that weight loss can improve several obesity-related health problems.[12][13] However, there are significant challenges in maintaining weight losses over the long term.[14][15] A report from the American College of Cardiology found that with a variety of diets, weight loss is maximal at six months, after which slow weight regain is observed.[12] A 2001 meta-analysis of 29 American studies found that participants of structured weight-loss programs maintained an average of 23% (3 kg) of their initial weight loss after five years, representing an sustained 3.2% reduction in body mass.[16] This 3.2% reduction in weight is insufficient for changing someone with an "obese" BMI to a "normal weight" BMI.

Stephan Rössner, an obesity researcher, argues that efforts targeting weight loss may cause rapid swings in size that inflict worse physical and psychological damage than obesity itself.[17] A 2007 review of existing research on dieting concluded that it "does not lead to sustained weight loss in the majority of individuals" and that because "the majority of individuals who engage in diets tend to regain most of their lost weight, no diet can be recommended without considering the potential harms of weight cycling", which it identified as an avenue for future research, along with the (more promising) potential of exercise as a means to treat obesity.[18]

Some non-dieting lifestyle interventions have been shown to help with weight maintenance.[19][20][21]

Criticism

Obesity as a health issue that needs to be managed

In May 2017, scientists at the European Congress on Obesity expressed scepticism about the possibility of being "fat but fit".[22]

Using data from 527,662 working adults in Spain, a 2021 study in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology found that an active lifestyle cannot cancel the negative effects on cardiovascular health caused by obesity.[23][24] Study author Alejandro Lucia stated:[25]

One cannot be "fat but healthy." This was the first nationwide analysis to show that being regularly active is not likely to eliminate the detrimental health effects of excess body fat. Our findings refute the notion that a physically active lifestyle can completely negate the deleterious effects of overweight and obesity.

Proponents have indicated that HAES does not propose that people are automatically healthy at any size, but rather proposes that people should seek to adopt healthy behaviors irregardless of their body weight.[26]

Claims that HAES may discourage weight loss

Amanda Sainsbury-Salis, an Australian medical researcher, calls for a rethink of the HAES concept,[27] arguing it is not possible to be and remain truly healthy at every size, and suggests that a HAES focus may encourage people to ignore increasing weight, which her research states is easiest to lose soon after gaining. She does, however, note that it is possible to have healthy behaviours that provide health benefits at a wide variety of body sizes. Others similarly argue that the HAES focus may encourage people to delay attempts at weight loss indefinitely.[3]

However, several studies have concluded that HAES interventions might be useful in weight maintenance (and possibly short-term weight loss) for at least some populations.[28][29]

References

- ↑ Penney, Tarra L.; Kirk, Sara F. L. (2015). "The Health at Every Size Paradigm and Obesity: Missing Empirical Evidence May Help Push the Reframing Obesity Debate Forward". American Journal of Public Health. 105 (5): e38–e42. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302552. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 4386524. PMID 25790393.

- ↑ Brown, Lora Beth (March–April 2009). "Teaching the 'Health at Every Size' Paradigm Benefits Future Fitness and Health Professionals". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 41 (2): 144–145. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2008.04.358. PMID 19304261.

- 1 2 Sainsbury, Amanda; Hay, Phillipa (March 18, 2014). "Call for an urgent rethink of the 'health at every size' concept". Journal of Eating Disorders. 2 (1): 8. doi:10.1186/2050-2974-2-8. ISSN 2050-2974. PMC 3995323. PMID 24764532.

- ↑ Louderback, Lew (November 4, 1967). "More People Should Be Fat". The Saturday Evening Post.

- ↑ Bob Schwartz (1996). Diets don't work. Breakthru Pub. ISBN 978-0-942540-16-1. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ↑ Bruno, Barbara Altman (April 30, 2013) [2009]. "the HAES® files: History of the Health At Every Size® Movement—the 1970s & 80s (Part 2)". Health at Every Size Blog. Archived from the original on March 19, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ↑ "Size Diversity & Health at Every Size". National Eating Disorders Association. February 18, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ↑ Nagoski, Emily (March 3, 2015). Come as you are : the surprising new science that will transform your sex life. New York. ISBN 978-1-4767-6209-8. OCLC 879642467.

- ↑ Sainsbury, Amanda (2014). "Erratum to: Call for an urgent rethink of the'health at every size'concept". Journal of Eating Disorders. 2.

- ↑ Tylka, TL; Annunziato, RA; Burgard, D; Daníelsdóttir, S; Shuman, E; Davis, C; Calogero, RM (2014). "The weight-inclusive versus weight-normative approach to health: evaluating the evidence for prioritizing well-being over weight loss". Journal of Obesity. 2014: 983495. doi:10.1155/2014/983495. PMC 4132299. PMID 25147734.

- ↑ Bacon L, Aphramor L (2011). "Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift". Nutr J. 10: 9. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-10-9. PMC 3041737. PMID 21261939.

- 1 2 Jensen, MD; et al. (June 24, 2014). "2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society". Circulation (Professional society guideline). 129 (25 Suppl 2): S102-38. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. PMC 5819889. PMID 24222017.

- ↑ Ingram DD, Mussolino ME (2010). "Weight loss from maximum body weight and mortality: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Linked Mortality File". Int J Obes. 34 (6): 1044–1050. doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.41. PMID 20212495.

- ↑ Thom, G; Lean, M (May 2017). "Is There an Optimal Diet for Weight Management and Metabolic Health?" (PDF). Gastroenterology (Review). 152 (7): 1739–1751. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.056. PMID 28214525.

- ↑ Kuchkuntla, AR; Limketkai, B; Nanda, S; Hurt, RT; Mundi, MS (December 2018). "Fad Diets: Hype or Hope?". Current Nutrition Reports (Review). 7 (4): 310–323. doi:10.1007/s13668-018-0242-1. PMID 30168044. S2CID 52132504.

- ↑ Anderson, James; Elizabeth C Konz; Robert C Frederich; Constance L Wood (November 2001). "Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 74 (5): 579–584. doi:10.1093/ajcn/74.5.579. PMID 11684524.

- ↑ "Does sustained weight loss lead to decreased morbidity and mortality?". International Journal of Obesity. 23 (S5): s20–s21. 1993. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0800982.

- ↑ Mann, Traci; Tomiyama, Janet A.; Westling, Erika; Lew, Ann-Marie; Samuels, Barbra; Chatman, Jason (April 2007). "Medicare's search for effective obesity treatments: Diets are not the answer". American Psychologist. Eating Disorders. 62 (3): 220–233. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.666.7484. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.62.3.220. PMID 17469900.

- ↑ Borkoles, E; Carroll, S; Clough, P; Polman, RC (2016). "Effect of a non-dieting lifestyle randomised control trial on psychological well-being and weight management in morbidly obese pre-menopausal women". Maturitas. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.09.010. PMID 26602363.

- ↑ Greaney, ML; Lees, FD; Lynch, B; Sebelia, L; Greene, GW (2012). "Using focus groups to identify factors affecting healthful weight maintenance in Latino immigrants". J Nutr Educ Behav. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2011.11.008. PMID 22640885.

- ↑ Swift, DL (2014). "The role of exercise and physical activity in weight loss and maintenance". Progress in cardiovascular diseases.

- ↑ Mundasad, Smitha (May 17, 2017). "Fat but fit is a big fat myth". BBC News. Archived from the original on March 19, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018 – via bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ Lucia, Alejandro; Valenzuela, Pedro L.; Santos-Lozano, Alejandro; et al. (January 22, 2021). "Joint association of physical activity and body mass index with cardiovascular risk: a nationwide population-based cross-sectional study". European Journal of Preventive Cardiology: zwaa151. doi:10.1093/eurjpc/zwaa151. PMID 33580798.

- ↑ Guy, Jack; Woodyatt, Amy (January 22, 2021). "'Fat but fit' is a myth when it comes to heart health, new study shows". CNN. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ↑ Antipolis, Sophia (January 22, 2021). "Being fat linked with worse heart health even in people who exercise". European Society of Cardiology. Retrieved January 22, 2021 – via Medical Xpress.

- ↑ O'Hara, L; Taylor, JA (2014). "Health at every size: A weight-neutral approach for empowerment, resilience and peace". International Journal of Social Work and Human Services Practice. 2 (6).

- ↑ Sainsbury, Amanda (March 18, 2014). "Call for an urgent rethink of the "health at every size" concept". J Eat Disord. 2 (8): 8. doi:10.1186/2050-2974-2-8. PMC 3995323. PMID 24764532.

- ↑ Borkoles, E; Carroll, S; Clough, P; Polman, RC (2016). "Effect of a non-dieting lifestyle randomised control trial on psychological well-being and weight management in morbidly obese pre-menopausal women". Maturitas. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.09.010. PMID 26602363.

- ↑ Greaney, ML; Lees, FD; Lynch, B; Sebelia, L; Greene, GW (2012). "Using focus groups to identify factors affecting healthful weight maintenance in Latino immigrants". J Nutr Educ Behav. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2011.11.008. PMID 22640885.

See also

- Fat acceptance movement