Muscular dystrophy

| Muscular dystrophy | |

|---|---|

| |

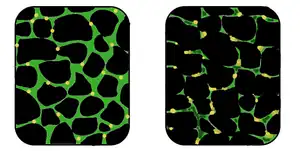

| In affected muscle (right), the tissue has become disorganized and the concentration of dystrophin (green) is greatly reduced, compared to normal muscle (left). | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, medical genetics |

| Symptoms | Increasing weakening, breakdown of skeletal muscles, trouble walking[1][2] |

| Duration | Long term[1] |

| Types | > 30 including Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Becker muscular dystrophy, facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, myotonic dystrophy[1][2] |

| Causes | Genetic (X-linked recessive, autosomal recessive, or autosomal dominant)[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests, genetic testing[2] |

| Treatment | Physical therapy, braces, corrective surgery, assisted ventilation[1][2] |

| Prognosis | Depends on the type[1] |

Muscular dystrophy (MD) is a group of muscle diseases that results in increasing weakening and breakdown of skeletal muscles over time.[1] The disorders differ in which muscles are primarily affected, the degree of weakness, how fast they worsen, and when symptoms begin.[1] Many people will eventually become unable to walk.[2] Some types are also associated with problems in other organs.[2]

The muscular dystrophy group contains thirty different genetic disorders that are usually classified into nine main categories or types.[1][2] The most common type is Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), which typically affects males beginning around the age of four.[1] Other types include Becker muscular dystrophy, facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, and myotonic dystrophy.[1] They are due to mutations in genes that are involved in making muscle proteins.[2] This can occur due to either inheriting the defect from one's parents or the mutation occurring during early development.[2] Disorders may be X-linked recessive, autosomal recessive, or autosomal dominant.[2] Diagnosis often involves blood tests and genetic testing.[2]

There is no cure for muscular dystrophy.[1] Physical therapy, braces, and corrective surgery may help with some symptoms.[1] Assisted ventilation may be required in those with weakness of breathing muscles.[2] Medications used include steroids to slow muscle degeneration, anticonvulsants to control seizures and some muscle activity, and immunosuppressants to delay damage to dying muscle cells.[1] Outcomes depend on the specific type of disorder.[1]

Duchenne muscular dystrophy, which represents about half of all cases of muscular dystrophy, affects about one in 5,000 males at birth.[2] Muscular dystrophy was first described in the 1830s by Charles Bell.[2] The word "dystrophy" is from the Greek dys, meaning "difficult" and troph meaning "nourish".[2] Gene therapy, as a treatment, is in the early stages of study in humans.[2]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms consistent with muscular dystrophy are:[3]

- Progressive muscular wasting

- Poor balance

- Scoliosis (curvature of the spine and the back)

- Progressive inability to walk

- Waddling gait

- Calf deformation

- Limited range of movement

- Respiratory difficulty

- Cardiomyopathy

- Muscle spasms

- Gowers' sign

Cause

These conditions are generally inherited, and the different muscular dystrophies follow various inheritance patterns. Muscular dystrophy can be inherited by individuals as an X-linked disorder, a recessive or dominant disorder. Furthermore, it can be a spontaneous mutation which means errors in the replication of DNA and spontaneous lesions. Spontaneous lesions are due to natural damage to DNA, where the most common are depurination and deamination.[4][5]

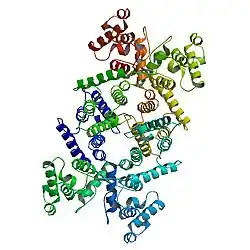

Dystrophin protein is found in muscle fiber membrane; its helical nature allows it to act like a spring or shock absorber. Dystrophin links actin in the cytoskeleton and dystroglycans of the muscle cell plasma membrane, known as the sarcolemma (extracellular). In addition to mechanical stabilization, dystrophin also regulates calcium levels.[6][7] The gene for dystrophin is located on the X chromosome. In males, the lone X chromosome has only one dystrophin gene. If there's a mutation in that gene, a male's muscles will lack dystrophin and slowly degenerate; mutations in the gene for dystrophin were identified as the cause of DMD by MDA researchers in 1986. A female almost always has two dystrophin genes, one on each X chromosome, and, even if one of these isn't working, the other gene suffices to keep dystrophin levels high enough to preserve muscle function in both the heart and skeletal muscles. Nevertheless, research has shown that a small minority of females having both a working and a non-working dystrophin gene can exhibit symptoms of DMD. Recent studies on the interaction of proteins with missense mutations and its neighbors showed high degree of rigidity associated with central hub proteins involved in protein binding and flexible subnetworks having molecular functions involved with calcium.[8]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of muscular dystrophy is based on the results of muscle biopsy, increased creatine phosphokinase (CpK3), electromyography, and genetic testing. A physical examination and the patient's medical history will help the doctor determine the type of muscular dystrophy. Specific muscle groups are affected by different types of muscular dystrophy.[9]

Other tests that can be done are chest X-ray, echocardiogram, CT scan, and magnetic resonance image scan, which via a magnetic field can produce images whose detail helps diagnose muscular dystrophy.[10] Quality of life can be measured using specific questionnaires.[11]

Classification

| Disorder name | OMIM | Gene | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Becker muscular dystrophy | 300376 | DMD | Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) is a less severe variant of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and is caused by the production of a truncated, but partially functional form of dystrophin.[12] Survival is usually into old age and affects only boys (with extremely rare exceptions)[13] |

| Congenital muscular dystrophy | Multiple | Multiple | .jpg.webp) Hydrocephalus Age at onset is birth, the symptoms include general muscle weakness and possible joint deformities, disease progresses slowly, and lifespan is shortened. Congenital muscular dystrophy includes several disorders with a range of symptoms. Muscle degeneration may be mild or severe. Problems may be restricted to skeletal muscle, or muscle degeneration may be paired with effects on the brain and other organ systems.[14] Several forms of the congenital muscular dystrophies are caused by defects in proteins thought to have some relationship to the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex and to the connections between muscle cells and their surrounding cellular structure. Some forms of congenital muscular dystrophy show severe brain malformations, such as lissencephaly and hydrocephalus.[12] |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | 310200 | DMD | Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the most common childhood form of muscular dystrophy; it generally affects only boys (with extremely rare exceptions), becoming clinically evident when a child begins walking. By age 10, the child may need braces for walking and by age 12, most patients are unable to walk.[15] Lifespans range from 15 to 45, though a few exceptions occur.[15] Researchers have identified the gene for the protein dystrophin, which, when absent, causes DMD.[16] Since the gene is on the X chromosome, this disorder affects primarily males, and females who are carriers have milder symptoms. Sporadic mutations in this gene occur frequently.[17]

Dystrophin is part of a complex structure involving several other protein components. The "dystrophin-glycoprotein complex" helps anchor the structural skeleton (cytoskeleton) within the muscle cells, through the outer membrane (sarcolemma) of each cell, to the tissue framework (extracellular matrix) that surrounds each cell. Due to defects in this assembly, contraction of the muscle leads to disruption of the outer membrane of the muscle cells and eventual weakening and wasting of the muscle.[12] |

| Distal muscular dystrophy | 254130 | DYSF | Distal muscular dystrophies' age at onset is about 20 to 60 years; symptoms include weakness and wasting of muscles of the hands, forearms, and lower legs; progress is slow and not life-threatening.[18]

Miyoshi myopathy, one of the distal muscular dystrophies, causes initial weakness in the calf muscles, and is caused by defects in the same gene responsible for one form of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy.[12] |

| Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy | 310300, 181350 | EMD, LMNA | Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy patients normally present in childhood and the early teenaged years with contractures. Clinical signs include muscle weakness and wasting, starting in the distal limb muscles and progressing to involve the limb-girdle muscles. Most patients also suffer from cardiac conduction defects and arrhythmias.[19][20]

The three subtypes of Emery–Dreifuss MD are distinguishable by their pattern of inheritance: X-linked, autosomal dominant, and autosomal recessive. The X-linked form is the most common. Each type varies in prevalence and symptoms. The disease is caused by mutations in the LMNA gene, or more commonly, the EMD gene. Both genes encode for protein components of the nuclear envelope. However, how these mutations cause the pathogenesis is not well understood.[21] |

| Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy | 158900 | DUX4 | Timelapse expression of DUX4 protein in FSHD cells Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) causes progressive weakness, initially in the muscles of the face, shoulders, and upper arms. Additional muscles are often affected.[22] Symptoms usually manifest in adolescence.[12] Affected individuals can become severely disabled, with 20% requiring a wheel chair by age 50.[23] The pattern of inheritance is autosomal dominant for the most common subtype (FSHD1); 30% of cases involve spontaneous mutations.[23] Penetrance and severity seem to be lower in females compared to males.[23][24] The cause is derepression of DUX4, which requires two mutations: one mutation causing demethylation of the DUX4 region, allowing DUX4 transcription, and another mutation forming a polyadenylation sequence downstream of DUX4, allowing stability to DUX4 messenger RNA and increased likelihood of translation.[23][25] |

| Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy | Multiple | Multiple | Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD) affects both boys and girls.[26] LGMDs all show a similar distribution of muscle weakness, affecting both upper arms and legs. Many forms of LGMD have been identified, showing different patterns of inheritance (autosomal recessive vs. autosomal dominant). In an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, an individual receives two copies of the defective gene, one from each parent. The recessive LGMDs are more frequent than the dominant forms, and usually have childhood or teenaged onset. The dominant LGMDs usually show adult onset. Some of the recessive forms have been associated with defects in proteins that make up the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex.[12] Though a person normally leads a normal life with some assistance, in some extreme cases, death from LGMD occurs due to cardiopulmonary complications.[27] |

| Myotonic muscular dystrophy | 160900, 602668 | DMPK, ZNF9 | Myotonic muscular dystrophy is an autosomal dominant condition that presents with myotonia (delayed relaxation of muscles), as well as muscle wasting and weakness.[28] Myotonic MD varies in severity and manifestations and affects many body systems in addition to skeletal muscles, including the heart, endocrine organs, and eyes.[29]

Myotonic MD type 1 (DM1) is the most common adult form of muscular dystrophy. It results from the expansion of a short (CTG) repeat in the DNA sequence of the myotonic dystrophy protein kinase gene. Myotonic muscular dystrophy type 2 (DM2) is rarer and is a result of the expansion of the CCTG repeat in the zinc finger protein 9 gene.[12] |

| Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy | 164300 | PABPN1 | Oculopharyngeal MD's age at onset is 40 to 70 years; symptoms affect muscles of eyelids, face, and throat followed by pelvic and shoulder muscle weakness; it has been attributed to a short repeat expansion in the genome which regulates the translation of some genes into functional proteins.[12] |

Management

Currently, there is no cure for muscular dystrophy. In terms of management, physical therapy, occupational therapy, orthotic intervention (e.g., ankle-foot orthosis),[30][31] speech therapy, and respiratory therapy may be helpful.[30] Low intensity corticosteroids such as prednisone, and deflazacort may help to maintain muscle tone.[32] Orthoses (orthopedic appliances used for support) and corrective orthopedic surgery may be needed to improve the quality of life in some cases.[2] The cardiac problems that occur with EDMD and myotonic muscular dystrophy may require a pacemaker.[33] The myotonia (delayed relaxation of a muscle after a strong contraction) occurring in myotonic muscular dystrophy may be treated with medications such as quinine.[34]

Occupational therapy assists the individual with MD to engage in activities of daily living (such as self-feeding and self-care activities) and leisure activities at the most independent level possible. This may be achieved with use of adaptive equipment or the use of energy-conservation techniques. Occupational therapy may implement changes to a person's environment, both at home or work, to increase the individual's function and accessibility; furthermore, it addresses psychosocial changes and cognitive decline which may accompany MD, and provides support and education about the disease to the family and individual.[35])

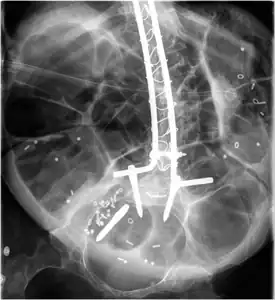

Radiograph of abdomen, of individual with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, spine stabilization is achived via rods and screws (one is displaced) and a Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is visible

Radiograph of abdomen, of individual with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, spine stabilization is achived via rods and screws (one is displaced) and a Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is visible Ankle foot orthosis

Ankle foot orthosis

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the individual form of MD. In some cases, a person with a muscle disease will get progressively weaker to the extent that it shortens lifespan due to heart and breathing complications. However, some of the muscle diseases do not affect life expectancy at all, and ongoing research is attempting to find cures and treatments to slow muscle weakness.[2]

History

In the 1860s, descriptions of boys who grew progressively weaker, lost the ability to walk, and died at an early age became more prominent in medical journals. In the following decade,[36] French neurologist Guillaume Duchenne gave a comprehensive account of the most common and severe form of the disease, which now carries his name—Duchenne MD.[37]

Research

WHO International conducted trials on optimum steroid regimen for MD, in the UK in 2012.[38] In terms of research within the United States, the primary federally funded organizations that focus on muscular dystrophy research, including gene therapy and regenerative medicine, are the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.[12]

In 1966, the Muscular Dystrophy Association began its annual Jerry Lewis MDA Telethon, which has probably done more to raise awareness of muscular dystrophy than any other event or initiative. Disability rights advocates, however, have criticized the telethon for portraying victims of the disease as deserving pity rather than respect.[39]

On December 18, 2001, the MD CARE Act was signed into law in the USA; it amends the Public Health Service Act to provide research for the various muscular dystrophies. This law also established the Muscular Dystrophy Coordinating Committee to help focus research efforts through a coherent research strategy.[40][41]

See also

- Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy

- Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy

- Muscle hypertrophy

- Muscular Dystrophy UK

- Muscular Dystrophy Canada

- Muscular Dystrophy Family Foundation

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "NINDS Muscular Dystrophy Information Page". NINDS. March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 "Muscular Dystrophy: Hope Through Research". NINDS. March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Muscular Dystrophy Clinical Presentation at eMedicine

- ↑ Choices, NHS. "Muscular dystrophy - Causes - NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 2016-04-02. Retrieved 2016-04-10.

- ↑ Griffiths, Anthony JF; Miller, Jeffrey H.; Suzuki, David T.; Lewontin, Richard C.; Gelbart, William M. (2000). Spontaneous mutations. Archived from the original on 2017-04-02. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ↑ "DMD gene". Genetics Home Reference. 2016-03-28. Archived from the original on 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2016-04-10.

- ↑ Lapidos, Karen A.; Kakkar, Rahul; McNally, Elizabeth M. (30 April 2004). "The Dystrophin Glycoprotein Complex". Circulation Research. 94 (8): 1023–1031. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000126574.61061.25. PMID 15117830.

- ↑ Sharma, Ankush (2014). "Publication:Rigidity and flexibility in protein-protein interaction networks: a case study on neuromuscular disorders". www.openaire.eu. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ↑ "NIH /How is muscular dystrophy diagnosed?". NIH.gov. NIH. 2015. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ↑ "Diagnosis Muscular Dystrophy". NHS Choices. NHS.uk. 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ↑ Dany, Antoine; Barbe, Coralie; Rapin, Amandine; Réveillère, Christian; Hardouin, Jean-Benoit; Morrone, Isabella; Wolak-Thierry, Aurore; Dramé, Moustapha; Calmus, Arnaud; Sacconi, Sabrina; Bassez, Guillaume; Tiffreau, Vincent; Richard, Isabelle; Gallais, Benjamin; Prigent, Hélène; Taiar, Redha; Jolly, Damien; Novella, Jean-Luc; Boyer, François Constant (4 July 2015). "Construction of a Quality of Life Questionnaire for slowly progressive neuromuscular disease". Quality of Life Research. 24 (11): 2615–2623. doi:10.1007/s11136-015-1013-8. PMID 26141500. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 May 2006 report to Congress Archived 2014-04-05 at the Wayback Machine on Implementation of the MD CARE Act, as submitted by Department of Health and Human Service's National Institutes of Health

- ↑ "Becker muscular dystrophy: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ↑ Congenital Muscular Dystrophy~clinical at eMedicine

- 1 2 "Duchenne muscular dystrophy: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-04-05. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ↑ "Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy - Genetics Home Reference". Ghr.nlm.nih.gov. 2017-03-07. Archived from the original on 2017-03-24. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ↑ "Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. What is muscular dystrophy? | Patient". Patient.info. 2016-04-15. Archived from the original on 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ↑ Udd, Bjarne (2011). "Distal muscular dystrophies". Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 101. pp. 239–62. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-045031-5.00016-5. ISBN 978-0-08-045031-5. PMID 21496636.

- ↑ "OMIM Entry - # 310300 - EMERY-DREIFUSS MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY 1, X-LINKED; EDMD1". Omim.org. Archived from the original on 2017-03-10. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ↑ "Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy - Genetics Home Reference". Ghr.nlm.nih.gov. 2017-03-07. Archived from the original on 2017-03-12. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ↑ Emery–Dreifuss Muscular Dystrophy at eMedicine

- ↑ "facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy - Genetics Home Reference". Ghr.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-03-24. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- 1 2 3 4 Statland, JM; Tawil, R (December 2016). "Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy". Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 22 (6, Muscle and Neuromuscular Junction Disorders): 1916–1931. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000399. PMC 5898965. PMID 27922500.

- ↑ "Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". Nlm.nih.gov. 2017-03-09. Archived from the original on 2016-07-04. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Roger N.; Pascual, Juan M. (2014-10-28). Rosenberg's Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurological and Psychiatric Disease. p. 1174. ISBN 978-0124105492. Archived from the original on 2017-03-15. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ↑ Pegoraro, E; Hoffman, EP; Adam, MP; Ardinger, HH; Pagon, RA; Wallace, SE; Bean, LJH; Stephens, K; Amemiya, A (2012). "Limb-Girdle Muscular Dystrophy Overview". PMID 20301582.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Jenkins, Simon P.R. (2005). Sports Science Handbook:I - Z. Brentwood, Essex: Multi-Science Publ. Co. p. 121. ISBN 978-0906522-37-0.

- ↑ Turner, C.; Hilton-Jones, D. (2010). "The myotonic dystrophies: diagnosis and management" (PDF). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 81 (4): 358–67. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.158261. PMID 20176601. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-10-23. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ↑ "Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1". Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1 - GeneReviews® - NCBI Bookshelf. Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. University of Washington, Seattle. 1993. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- 1 2 "What are the treatments for muscular dystrophy?". NIH.gov. NIH. 2015. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ↑ "Muscular Dystrophy-OrthoInfo - AAOS". orthoinfo.aaos.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2016-04-10.

- ↑ McAdam, Laura C.; Mayo, Amanda L.; Alman, Benjamin A.; Biggar, W. Douglas (2012). "The Canadian experience with long term deflazacort treatment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy". Acta Myologica. 31 (1): 16–20. PMC 3440807. PMID 22655512.

- ↑ Verhaert, David; Richards, Kathryn; Rafael-Fortney, Jill A.; Raman, Subha V. (January 2011). "Cardiac Involvement in Patients With Muscular Dystrophies". Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 4 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.110.960740. PMC 3057042. PMID 21245364.

- ↑ Eddy, Linda L. (2013). Caring for Children with Special Healthcare Needs and Their Families: A Handbook for Healthcare Professionals. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-51797-0.

- ↑ Lehman, R. M.; McCormack, G. L. (2001). "Neurogenic and Myopathic Dysfunction". In Pedretti, Lorraine Williams; Early, Mary Beth (eds.). Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction (5th ed.). Mosby. pp. 802–3. ISBN 978-0-323-00765-8.

- ↑ Laing, Nigel G; Davis, Mark R; Bayley, Klair; Fletcher, Sue; Wilton, Steve D (2011). "Molecular Diagnosis of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Past, Present and Future in Relation to Implementing Therapies". The Clinical Biochemist Reviews. 32 (3): 129–134. PMC 3157948. PMID 21912442.

- ↑ "Muscular Dystrophy: Hope Through Research". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 23 March 2020. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ↑ Choices, N. H. S. (2011-11-09). "Muscular Dystrophy - Clinical trial details - NHS Choices". Archived from the original on 2016-04-21. Retrieved 2016-04-10.

- ↑ Berman, Ari (2011-09-02). "The End of the Jerry Lewis Telethon—It's About Time". The Nation. Archived from the original on 2015-04-18. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ↑ H.R. 717--107th Congress (2001) Archived 2012-02-19 at the Wayback Machine: MD-CARE Act, GovTrack.us (database of federal legislation), (accessed Jul 29, 2007)

- ↑ Public Law 107-84 Archived 2012-11-07 at the Wayback Machine, PDF as retrieved from NIH website

Further reading

- De Los Angeles Beytía, Maria; Vry, Julia; Kirschner, Janbernd (2012). "Drug treatment of Duchenne musculardystrophy: available evidence and perspectives". Acta Myologica. 31 (1): 4–8. PMC 3440798. PMID 22655510.

- Bertini, Enrico; D'Amico, Adele; Gualandi, Francesca; Petrini, Stefania (December 2011). "Congenital Muscular Dystrophies: A Brief Review". Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 18 (4): 277–288. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2011.10.010. PMC 3332154. PMID 22172424.

External links

- Muscular dystrophies at Curlie

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |