Notochord

| Notochord | |

|---|---|

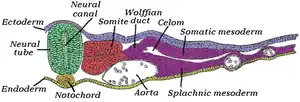

Transverse section of a chick embryo of forty-five hours’ incubation. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | axial mesoderm |

| Gives rise to | nucleus pulposus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | notochorda |

| MeSH | D009672 |

| TE | E5.0.1.1.0.0.8 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In anatomy, the notochord is a flexible rod formed of a material similar to cartilage. If a species has a notochord at any stage of its life cycle, it is, by definition, a chordate. The notochord lies along the anteroposterior axis (front to back), is usually closer to the dorsal than the ventral surface of the embryo, and is composed of cells derived from the mesoderm.

The most commonly cited functions of the notochord are: as a midline tissue that provides directional signals to surrounding tissue during development, as a site of muscle attachment, and as a vertebral precursor.[1]

In lancelets the notochord persists throughout life as the main structural support of the body. In tunicates the notochord is present only in the larval stage, being completely absent in the adult animal. In all vertebrates other than hagfish, the notochord develops into the vertebral column, becoming vertebrae and the intervertebral discs the center of which retains a structure similar to the original notochord.[2][1]

Structure

The notochord is a long, rodlike structure that develops dorsal to the gut and ventral to the neural tube. The notochord is composed primarily of a core of glycoproteins, encased in a sheath of collagen fibers wound into two opposing helices. The glycoproteins are stored in vacuolated, turgid cells. The angle between these fibers determines whether increased pressure in the core will result in shortening and thickening versus lengthening and thinning.[3]

Contraction of these muscle fibers result in a side-to-side motion resembling swimming. The stiffened notochord prevents movement through telescoping motion, such as that of an earthworm.[4]

Role in signaling & development

The notochord plays a key role in signaling and coordinating development. Embryos of modern vertebrates form transient notochord structures during gastrulation. The notochord is found ventral to the neural tube.

Notogenesis is the development of the notochord by epiblasts that form the floor of the amnion cavity.[5] The progenitor notochord is derived from cells migrating from the primitive node and pit.[6] The notochord forms during gastrulation and soon after induces the formation of the neural plate (neurulation), synchronizing the development of the neural tube. On the ventral aspect of the neural groove an axial thickening of the endoderm takes place. (In bipedal chordates, e.g. humans, this surface is properly referred to as the anterior surface). This thickening appears as a furrow (the chordal furrow) the margins of which anastomose (come into contact), and so convert it into a solid rod of polygonal-shaped cells (the notochord) which is then separated from the endoderm.

In vertebrates, it extends throughout the entire length of the future vertebral column, and reaches as far as the anterior end of the midbrain, where it ends in a hook-like extremity in the region of the future dorsum sellae of the sphenoid bone. Initially, it exists between the neural tube and the endoderm of the yolk-sac; soon, the notochord becomes separated from them by the mesoderm, which grows medially and surrounds it. From the mesoderm surrounding the neural tube and notochord, the skull, vertebral column, and the membranes of the brain and medulla spinalis are developed.[7] Because it originates from the primitive node and is ultimately positioned with the mesodermal space, it is considered to be derived from mesoderm.[8]

A postembryonic vestige of the notochord is found in the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral discs. Isolated notochordal remnants may escape their lineage-specific destination in the nucleus pulposus and instead attach to the outer surfaces of the vertebral bodies, from which notochordal cells largely regress.[9]

In amphibians and fish

During development of amphibians and fish, the notochord induces development of the hypochord through secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor. The hypochord is a transient structure ventral to the notochord, and is primarily responsible for correct development of the dorsal aorta.[10]

In humans

By the age of 4, all notochord residue is replaced by a population of chondrocyte-like cells of unclear origin.[11] Persistence of notochordal cells within the vertebra may cause a pathologic condition: persistent notochordal canal.[12] If the notochord and the nasopharynx do not separate properly during embryonic development, a depression (Tornwaldt bursa) or Tornwaldt cyst may form.[13] The cells are the likely precursors to a rare cancer called chordoma.[14]

Neurology

Research into the notochord has played a key role in understanding the development of the central nervous system. By transplanting and expressing a second notochord near the dorsal neural tube, 180 degrees opposite of the normal notochord location, one can induce the formation of motor neurons in the dorsal tube. Motor neuron formation generally occurs in the ventral neural tube, while the dorsal tube generally forms sensory cells.

The notochord secretes a protein called sonic hedgehog (SHH), a key morphogen regulating organogenesis and having a critical role in signaling the development of motor neurons.[15] The secretion of SHH by the notochord establishes the ventral pole of the dorsal-ventral axis in the developing embryo.

Evolution in chordates

The notochord is the defining feature (synapomorphy) of chordates, and was present throughout life in many of the earliest chordates. Although the stomochord of hemichordates was once thought to be homologous, it is now viewed as a convergence.[16] Pikaia appears to have a proto-notochord, and notochords are present in several basal chordates such as Haikouella, Haikouichthys, and Myllokunmingia, all from the Cambrian.

The Ordovician oceans included many diverse species of Agnatha and early Gnathostomata which possessed notochords, either with attached bony elements or without, most notably the conodonts,[17] placoderms,[18] and ostracoderms. Even after the evolution of the vertebral column in chondrichthyes and osteichthyes, these taxa remained common and are well represented in the fossils record. Several species (see list below) have reverted to the primitive state, retaining the notochord into adulthood, though the reasons for this are not well understood.

Scenarios for the evolutionary origin of the notochord were comprehensively reviewed by Annona, Holland, and D'Aniello (2015).[19] They point out that, although many of these ideas have not been well supported by advances in molecular phylogenetics and developmental genetics, two of them have actually been revived under the stimulus of modern molecular approaches (the first proposes that the notochord evolved de novo in chordates, and the second derives it from a homologous structure, the axochord, that was present in annelid-like ancestors of the chordates). Deciding between these two scenarios (or possibly another yet to be proposed) should be facilitated by much more thorough studies of gene regulatory networks in a wide spectrum of animals.

Post-embryonic retention

In most vertebrates, the notochord develops into secondary structures. In other chordates, the notochord is retained as an essential anatomical structure. The evolution of the notochord within the phylum Chordata is considered in detail by Holland and Somorjai (2020). [20]

The following organisms retain a post-embryonic notochord:

- Acipenseriformes (paddlefish and sturgeon)[21]

- Lancelet (Amphioxus)

- Tunicate (larval stage only)

- Hagfish

- Lamprey

- Coelacanth

- African lungfish

- Tadpoles

- Ostracoderms (extinct)

Within Amphioxus

The notochord of the lancelet protrudes beyond the anterior end of the neural tube. This projection serves a second purpose in allowing the animal to burrow within the sediment of shallow waters. There, amphioxus is a filter feeder and spends most of its life partially submerged within the sediment.[4]

Additional images

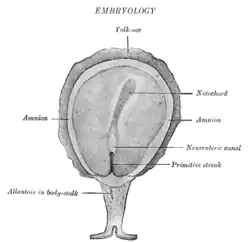

Surface view of embryo of Concolor gibbon (Hylobates concolor).

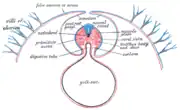

Surface view of embryo of Concolor gibbon (Hylobates concolor). Diagram of a transverse section, showing the mode of formation of the amnion in the chick.

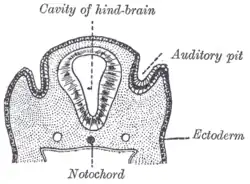

Diagram of a transverse section, showing the mode of formation of the amnion in the chick. Section through the head of a human embryo, about twelve days old, in the region of the hind-brain.

Section through the head of a human embryo, about twelve days old, in the region of the hind-brain. Transverse section of human embryo eight and a half to nine weeks old.

Transverse section of human embryo eight and a half to nine weeks old.

References

- 1 2 Stemple, Derek L. (2005-06-01). "Structure and function of the notochord: an essential organ for chordate". Development. 132 (11): 2503–2512. doi:10.1242/dev.01812. ISSN 0950-1991. PMID 15890825.

- ↑ Krämer, Jürgen (2009). Intervertebral Disk Diseases: Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prophylaxis. Thieme. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-3-13-582403-1.

- ↑ M. A. R. Koehl (2000). "Mechanical Design of Fiber-Wound Hydraulic Skeletons: The Stiffening and Straightening of Embryonic Notochords". American Zoologist. 40: 28–041. doi:10.1093/icb/40.1.28.

- 1 2 Homberger, Dominique G. (2004). Vertebrate dissection. Walker, Warren F. (Warren Franklin), Walker, Warren F. (Warren Franklin). (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-03-022522-1. OCLC 53074665.

- ↑ "The trilaminar germ disk (3rd week)". www.embryology.ch.

- ↑ Hood, Rousseaux, Blakley, Ronald D., Colin G., Patricia M. (29 May 2007). "Embryo and Fetus". Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology (Second Edition). Academic Press, Published by Elsevier Inc. 2: 895–936. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-330215-1.50047-8. ISBN 9780123302151.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Henry Gray (1918). Anatomy of the Human Body. Lea & Febiger. pp. 52–54.

- ↑ Gary C. Schoenwolf; Steven B. Bleyl; Philip R. Brauer; Philippa H. Francis-West (1 December 2014). Larsen's Human Embryology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-1-4557-2791-9.

- ↑ Choi, K.; Cohn, Martin J.; Harfe, Brian D. (2009). "Identification of Nucleus Pulposus Precursor Cells and Notochordal Remnants in the Mouse: Implications for Disk Degeneration and Chordoma Formation". Developmental Dynamics. 237 (12): 3953–3958. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21805. PMC 2646501. PMID 19035356.

- ↑ Cleaver, Ondine (2000). "Endoderm patterning by the notochord: development of the hypochord in Xenopus" (PDF). Development. 127 (4): 869–979. doi:10.1242/dev.127.4.869. PMID 10648245.

- ↑ Urban, J. P. G. (2000). "The Nucleus of the Intervertebral Disc from Development to Degeneration". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 40: 53–061. doi:10.1093/icb/40.1.53.

- ↑ Christopherson, Lr; Rabin, Bm; Hallam, Dk; Russell, Ej (1 January 1999). "Persistence of the notochordal canal: MR and plain film appearance" (Free full text). American Journal of Neuroradiology. 20 (1): 33–6. ISSN 0195-6108. PMID 9974055.

- ↑ Moody MW, Chi DH, Chi DM, Mason JC, Phillips CD, Gross CW, et al. (2007). "Tornwaldt's cyst: incidence and a case report". Ear Nose Throat J. 86 (1): 45–7, 52. doi:10.1177/014556130708600117. PMID 17315835.

- ↑ Pillai S, Govender S (2018). "Sacral chordoma : A review of literature". J Orthop. 15 (2): 679–684. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2018.04.001. PMC 5990241. PMID 29881220.

- ↑ Echelard, Y; Epstein, Dj; St-Jacques, B; Shen, L; Mohler, J; Mcmahon, Ja; Mcmahon, Ap (December 1993). "Sonic hedgehog, a member of a family of putative signaling molecules, is implicated in the regulation of CNS polarity". Cell. 75 (7): 1417–30. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90627-3. PMID 7916661. S2CID 6732599.

- ↑ Kardong, Kenneth V. (1995). Vertebrates: comparative anatomy, function, evolution. McGraw-Hill. pp. 55, 57. ISBN 978-0-697-21991-6.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-03-13. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Annona, G.; Holland, N.D.; D'Aniello, S. (2015). "Evolution of the notochord". EvoDevo. 6. article 30. doi:10.1186/s13227-015-0025-3. PMC 4595329. PMID 26446368.

- ↑ Holland, N. D.; Somorjai, I. M. L. (2020). "Serial blockface SEM suggests that stem cells may participate in adult notochord growth in an invertebrate chordate, the Bahamas lancelet". EvoDevo. 11. article 22. doi:10.1186/s13227-020-00167-6. PMC 7568382.

- ↑ Joseph J. Luczkovich; Philip J. Motta; Stephen F. Norton; Karel F. Liem (17 April 2013). Ecomorphology of fishes. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 201. ISBN 978-94-017-1356-6.