Body fat percentage

| Part of a series on |

| Human body weight |

|---|

The body fat percentage (BFP) of a human or other living being is the total mass of fat divided by total body mass, multiplied by 100; body fat includes essential body fat and storage body fat. Essential body fat is necessary to maintain life and reproductive functions. The percentage of essential body fat for women is greater than that for men, due to the demands of childbearing and other hormonal functions. Storage body fat consists of fat accumulation in adipose tissue, part of which protects internal organs in the chest and abdomen. A number of methods are available for determining body fat percentage, such as measurement with calipers or through the use of bioelectrical impedance analysis.

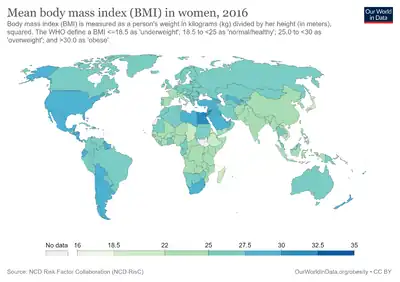

The body fat percentage is a measure of fitness level, since it is the only body measurement which directly calculates a person's relative body composition without regard to height or weight. The widely used body mass index (BMI) provides a measure that allows the comparison of the adiposity of individuals of different heights and weights. While BMI largely increases as adiposity increases, due to differences in body composition, other indicators of body fat give more accurate results; for example, individuals with greater muscle mass or larger bones will have higher BMIs. As such, BMI is a useful indicator of overall fitness for a large group of people, but a poor tool for determining the health of an individual.

Typical body fat amounts

Epidemiologically, the percentage of body fat in an individual varies according to sex and age.[1] Various theoretical approaches exist on the relationships between body fat percentage, health, athletic capacity, etc. Different authorities have consequently developed different recommendations for ideal body fat percentages.

This graph from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in the United States charts the average body fat percentages of Americans from samples from 1999 to 2004:

QuickStats: Mean Percentage Body Fat, by Age Group and Sex – National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 1999–2004 |

In males, mean percentage body fat ranged from 23% at age 16–19 years to 31% at age 60–79 years. In females, mean percentage body fat ranged from 32% at age 8–11 years to 42% at age 60–79 years. But it is important to recognise that women need at least 9% more body fat than men to live a normal healthy life.[2]

Data from the 2003–2006 NHANES survey showed that fewer than 10% of American adults had a "normal" body fat percentage (defined as 5–20% for men and 8–30% for women).[3]

Results from the 2017–2018 NHANES survey indicate that an estimated 43% of noninstitutionalized U.S. adults aged 20–74 are obese (including 9% who are severely obese) and an additional 31% are overweight.[4] Only 26% were either normal weight or are underweight.

In 1983, the body fat percentages of American Olympians averaged 14–22% for women and 6–13% for men.[5]

Body fat guidelines

Essential fat is the level at which physical and physiological health would be negatively affected, and below which death is certain. Above that level, controversy exists as to whether a particular body fat percentage is better for one's health.

Athletic performance might be affected by body fat: A study by the University of Arizona indicated that the ideal body fat percentage for athletic performance is 12–18% for women and 6–15% for men.[6]

Bodybuilders may compete at essential body fat range. Certified personal trainers will suggest competitors keep that extremely low level of body fat only for the contest time. However, it is unclear that such levels are ever actually attained since (a) the means to measure such levels are, as noted below, lacking in principle and inaccurate, and (b) 4–6% is generally considered a physiological minimum for human males.[7]

Measurement techniques

Underwater weighing

Irrespective of the location from which they are obtained, the fat cells in humans are composed almost entirely of pure triglycerides with an average density of about 0.9 kilograms per litre. Most modern body composition laboratories today use the value of 1.1 kilograms per litre for the density of the "fat free mass".[8]

With a well engineered weighing system, body density can be determined with great accuracy by completely submerging a person in water and calculating the volume of the displaced water from the weight of the displaced water. A correction is made for the buoyancy of air in the lungs and other gases in the body spaces. If there were no errors whatsoever in measuring body density, the uncertainty in fat estimation would be about ± 3.8% of the body weight, primarily because of normal variability in body constituents.

Whole-body air displacement plethysmography

Whole-body air displacement plethysmography (ADP) is a recognised and scientifically validated densitometric method to measure human body fat percentage.[9] ADP uses the same principles as the gold-standard method of underwater weighing, but representing a densitometric method that is based on air displacement rather than on water immersion. Air-displacement plethysmography offers several advantages over established reference methods, including a quick, comfortable, automated, noninvasive, and safe measurement process, and accommodation of various subject types (e.g., children, obese, elderly, and disabled persons).[10] However, its accuracy declines at the extremes of body fat percentages, tending to slightly understate the percent body fat in overweight and obese persons (by 1.68–2.94% depending on the method of calculation), and to overstate to a much larger degree the percent body fat in very lean subjects (by an average of 6.8%, with up to a 13% overstatement of the reported body percentage of one individual — i.e. 2% body fat by DXA but 15% by ADP).[11]

Near-infrared interactance

A beam of infra-red light is transmitted into a biceps. The light is reflected from the underlying muscle and absorbed by the fat. The method is safe, noninvasive, rapid and easy to use.[12]

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry, or DXA (formerly DEXA), is a newer method for estimating body fat percentage, and determining body composition and bone mineral density.

X-rays of two different energies are used to scan the body, one of which is absorbed more strongly by fat than the other. A computer can subtract one image from the other, and the difference indicates the amount of fat relative to other tissues at each point. A sum over the entire image enables calculation of the overall body composition.

Expansions

There are several more complicated procedures that more accurately determine body fat percentage. Some, referred to as multicompartment models, can include DXA measurement of bone, plus independent measures of body water (using the dilution principle with isotopically labeled water) and body volume (either by water displacement or air plethysmography). Various other components may be independently measured, such as total body potassium.

In-vivo neutron activation can quantify all the elements of the body and use mathematical relations among the measured elements in the different components of the body (fat, water, protein, etc.) to develop simultaneous equations to estimate total body composition, including body fat.[13]

Body average density measurement

Prior to the adoption of DXA, the most accurate method of estimating body fat percentage was to measure that person's average density (total mass divided by total volume) and apply a formula to convert that to body fat percentage.

Since fat tissue has a lower density than muscles and bones, it is possible to estimate the fat content. This estimate is distorted by the fact that muscles and bones have different densities: for a person with a more-than-average amount of bone mass, the estimate will be too low. However, this method gives highly reproducible results for individual persons (± 1%), unlike the methods discussed below, which can have an uncertainty of 10%, or more. The body fat percentage is commonly calculated from one of two formulas (ρ represents density in g/cm3):

Bioelectrical impedance analysis

The bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) method is a lower-cost (from less than one to several hundred US dollars in 2006[16]) but less accurate way to estimate body fat percentage. The general principle behind BIA: two or more conductors are attached to a person's body and a small electric current is sent through the body. The resistance between the conductors will provide a measure of body fat between a pair of electrodes, since the resistance to electricity varies between adipose, muscular and skeletal tissue. Fat-free mass (muscle) is a good conductor as it contains a large amount of water (approximately 73%) and electrolytes, while fat is anhydrous and a poor conductor of electric current. Factors that affect the accuracy and precision of this method include instrumentation, subject factors, technician skill, and the prediction equation formulated to estimate the fat-free mass.

Each (bare) foot may be placed on an electrode, with the current sent up one leg, across the abdomen and down the other leg. (For convenience, an instrument which must be stepped on will also measure weight.) Alternatively, an electrode may be held in each hand; calculation of fat percentage uses the weight, so that must be measured with scales and entered by the user. The two methods may give different percentages, without being inconsistent, as they measure fat in different parts of the body. More sophisticated instruments for domestic use are available with electrodes for both feet and hands.

There is little scope for technician error as such, but factors such as eating, drinking and exercising must be controlled[16] since hydration level is an important source of error in determining the flow of the electric current to estimate body fat. The instructions for use of instruments typically recommended not making measurements soon after drinking or eating or exercising, or when dehydrated. Instruments require details such as sex and age to be entered, and use formulae taking these into account; for example, men and women store fat differently around the abdomen and thigh region.

Different BIA analysers may vary. Population-specific equations are available for some instruments, which are only reliable for specific ethnic groups, populations, and conditions. Population-specific equations may not be appropriate for individuals outside of specific groups.[17]

Anthropometric methods

There exist various anthropometric methods for estimating body fat. The term anthropometric refers to measurements made of various parameters of the human body, such as circumferences of various body parts or thicknesses of skinfolds. Most of these methods are based on a statistical model. Some measurements are selected, and are applied to a population sample. For each individual in the sample, the method's measurements are recorded, and that individual's body density is also recorded, being determined by, for instance, under-water weighing, in combination with a multi-compartment body density model. From this data, a formula relating the body measurements to density is developed.

Because most anthropometric formulas such as the Durnin-Womersley skinfold method,[18] the Jackson-Pollock skinfold method, and the US Navy circumference method, actually estimate body density, not body fat percentage, the body fat percentage is obtained by applying a second formula, such as the Siri or Brozek described in the above section on density. Consequently, the body fat percentage calculated from skin folds or other anthropometric methods carries the cumulative error from the application of two separate statistical models.

These methods are therefore inferior to a direct measurement of body density and the application of just one formula to estimate body fat percentage. One way to regard these methods is that they trade accuracy for convenience, since it is much more convenient to take a few body measurements than to submerge individuals in water.

The chief problem with all statistically derived formulas is that in order to be widely applicable, they must be based on a broad sample of individuals. Yet, that breadth makes them inherently inaccurate. The ideal statistical estimation method for an individual is based on a sample of similar individuals. For instance, a skinfold based body density formula developed from a sample of male collegiate rowers is likely to be much more accurate for estimating the body density of a male collegiate rower than a method developed using a sample of the general population, because the sample is narrowed down by age, sex, physical fitness level, type of sport, and lifestyle factors. On the other hand, such a formula is unsuitable for general use.

Skinfold methods

The skinfold estimation methods are based on a skinfold test, also known as a pinch test, whereby a pinch of skin is precisely measured by calipers, also known as a plicometer,[19] at several standardized points on the body to determine the subcutaneous fat layer thickness.[20][21] These measurements are converted to an estimated body fat percentage by an equation. Some formulas require as few as three measurements, others as many as seven. The accuracy of these estimates is more dependent on a person's unique body fat distribution than on the number of sites measured. As well, it is of utmost importance to test in a precise location with a fixed pressure. Although it may not give an accurate reading of real body fat percentage, it is a reliable measure of body composition change over a period of time, provided the test is carried out by the same person with the same technique.

Skinfold-based body fat estimation is sensitive to the type of caliper used, and technique. This method also only measures one type of fat: subcutaneous adipose tissue (fat under the skin). Two individuals might have nearly identical measurements at all of the skin fold sites, yet differ greatly in their body fat levels due to differences in other body fat deposits such as visceral adipose tissue: fat in the abdominal cavity. Some models partially address this problem by including age as a variable in the statistics and the resulting formula. Older individuals are found to have a lower body density for the same skinfold measurements, which is assumed to signify a higher body fat percentage. However, older, highly athletic individuals might not fit this assumption, causing the formulas to underestimate their body density.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is used extensively to measure tissue structure and has proven to be an accurate technique to measure subcutaneous fat thickness.[22] A-mode and B-mode ultrasound systems are now used and both rely on using tabulated values of tissue sound speed and automated signal analysis to determine fat thickness. By making thickness measurements at multiple sites on the body you can calculate the estimated body fat percentage.[23][24] Ultrasound techniques can also be used to directly measure muscle thickness and quantify intramuscular fat. Ultrasound equipment is expensive, and not cost-effective solely for body fat measurement, but where equipment is available, as in hospitals, the extra cost for the capability to measure body fat is minimal.[16]

Height and circumference methods

There also exist formulas for estimating body fat percentage from an individual's weight and girth measurements. For example, the U.S. Navy circumference method compares abdomen or waist and hips measurements to neck measurement and height and other sites claim to estimate one's body fat percentage by a conversion from the body mass index. In the U.S. Navy, the method is known as the "rope and choke." There is limited information, however, on the validity of the "rope and choke" method because of its universal acceptance as inaccurate and easily falsified.

The U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps also rely on the height and circumference method.[25] For males, they measure the neck and waist just above the navel. Females are measured around the hips, waist, and neck. These measurements are then looked up in published tables, with the individual's height as an additional parameter. This method is used because it is a cheap and convenient way to implement a body fat test throughout an entire service.

Methods using circumference have little acceptance outside the Department of Defense due to their negative reputation in comparison to other methods. The method's accuracy becomes an issue when comparing people with different body compositions, those with larger necks artificially generate lower body fat percentage calculations than those with smaller necks.

From BMI

Body fat can be estimated from body mass index (BMI), a person's mass in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters; if weight is measured in pounds and height in inches, the result can be converted to BMI by multiplying by 703.[26] There are a number of proposed formulae that relate body fat to BMI. These formulae are based on work by researchers published in peer-reviewed journals, but their correlation with body fat are only estimates; body fat cannot be deduced accurately from BMI.

Body fat may be estimated from the body mass index by formulae derived by Deurenberg and co-workers. When making calculations, the relationship between densitometrically determined body fat percentage (BF%) and BMI must take age and sex into account. Internal and external cross-validation of the prediction formulas showed that they gave valid estimates of body fat in males and females at all ages. In obese subjects, however, the prediction formulas slightly overestimated the BF%. The prediction error is comparable to the prediction error obtained with other methods of estimating BF%, such as skinfold thickness measurements and bioelectrical impedance. The formula for children is different; the relationship between BMI and BF% in children was found to differ from that in adults due to the height-related increase in BMI in children aged 15 years and younger.[27]

- where sex is 0 for females and 1 for males.

However – contrary to the aforementioned internal and external cross-validation –, these formulae definitely proved unusable at least for adults and are presented here illustratively only.

Still, the following formula designed for adults proved to be much more accurate at least for adults:[28]

- where, again, gender (sex) is 0 if female and 1 if male to account for the lower body fat percentage of men.

Other indices may be used; the body adiposity index was said by its developers to give a direct estimate of body fat percentage, but statistical studies found this not to be so.[29]

See also

- Adipose tissue

- Andreas Münzer

- Body water

- Classification of obesity

- Lizzie Velásquez, a woman with "zero percent body fat"

- Relative Fat Mass (RFM)

References

- ↑ Jackson AS, Stanforth PR, Gagnon J, Rankinen T, Leon AS, Rao DC, Skinner JS, Bouchard C, Wilmore JH (June 2002). "The effect of sex, age and race on estimating percentage body fat from body mass index: The Heritage Family Study". International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 26 (6): 789–796. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802006. PMID 12037649.

- ↑ "QuickStats: Mean Percentage Body Fat, by Age Group and Sex – National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 1999–2004". cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2023-03-31. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- ↑ Loprinzi, P; Branscum, A; Hanks, J; Smit, E (2016). "Healthy Lifestyle Characteristics and Their Joint Association With Cardiovascular Disease Biomarkers in US Adults". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 91 (4): 432–442. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.01.009. PMID 26906650.

- ↑ Fryar; Carroll; Afful. "Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Severe Obesity Among Adults Aged 20 and Over: United States, 1960–1962 Through 2017–2018". Archived from the original on 2023-08-27. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Fleck, Stephen J. (November 1, 1983). "Body composition of elite American athletes". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 11 (6): 398–403. doi:10.1177/036354658301100604. PMID 6650717. S2CID 25043685. Archived from the original on July 29, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ↑ Bean, Anita (2009). The Complete Guide to Sports Nutrition (6th ed.). London: A & C Black. p. 108. ISBN 978-14081-0538-2. Archived from the original on June 30, 2023. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ↑ Friedl KE, Moore RJ, Martinez-Lopez LE, Vogel JA, Askew EW, Marchitelli LJ, Hoyt RW, Gordon CC (August 1994). "Lower limit of body fat in healthy active men". Journal of Applied Physiology. 77 (2): 933–940. doi:10.1152/jappl.1994.77.2.933. PMID 8002550.

- ↑ Wang, Zimian; Heshka, Stanley; Wang, Jack; Wielopolski, Lucian; Heymsfield, Steven B. (2003-02-01). "Magnitude and variation of fat-free mass density: a cellular-level body composition modeling study". American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. American Physiological Society. 284 (2): E267–E273. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00151.2002. ISSN 0193-1849.

- ↑ McCrory MA, Gomez TD, Bernauer EM, Molé PA (December 1995). "Evaluation of a new air displacement plethysmograph for measuring human body composition". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 27 (12): 1686–1691. doi:10.1249/00005768-199512000-00016. PMID 8614326.

- ↑ Fields DA, Goran MI, McCrory MA (March 2002). "Body-composition assessment via air-displacement plethysmography in adults and children: a review". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 75 (3): 453–467. doi:10.1093/ajcn/75.3.453. PMID 11864850.

- ↑ Lowry DW, Tomiyama AJ (January 21, 2015). "Air displacement plethysmography versus dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in underweight, normal-weight, and overweight/obese individuals". PLOS ONE. 10 (1): e0115086. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1015086L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115086. PMC 4301864. PMID 25607661.

- ↑ Conway JM, Norris KH, Bodwell CE (December 1984). "A new approach for the estimation of body composition: infrared interactance" (PDF). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 40 (6): 1123–1130. doi:10.1093/ajcn/40.6.1123. PMID 6507337. S2CID 4506987. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-22.

- ↑ Cohn SH, Vaswani AN, Yasumura S, Yuen K, Ellis KJ (August 1984). "Improved models for determination of body fat by in vivo neutron activation". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 40 (2): 255–259. doi:10.1093/ajcn/40.2.255. PMID 6465059.

- ↑ Brozek J, Grande F, Anderson JT, Keys A (September 1963). "Densitometric analysis of body composition: revision of some quantitative assumptions". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 110 (1): 113–140. Bibcode:1963NYASA.110..113B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1963.tb17079.x. PMID 14062375. S2CID 2191337.

- ↑ Siri WE (1961). "Body composition from fluid spaces and density: Analysis of methods". In Brozek J, Henzchel A (eds.). Techniques for Measuring Body Composition. Washington: National Academy of Sciences. pp. 224–244.

- 1 2 3 Brown SP, Miller WC, Eason JM (2006). Exercise physiology: basis of human movement in health and disease (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-7817-7730-8.

- ↑ Dehghan M, Merchant AT (September 2008). "Is bioelectrical impedance accurate for use in large epidemiological studies?". Nutrition Journal. 7: 26. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-7-26. PMC 2543039. PMID 18778488.

- ↑ Durnin JV, Womersley J (July 1974). "Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness: measurements on 481 men and women aged from 16 to 72 years". The British Journal of Nutrition. 32 (1): 77–97. doi:10.1079/BJN19740060. PMID 4843734.

- ↑ Zonatto HA, Ribas MR, Simm EB, Oliveira AG, Bassan JC (Oct–Dec 2017). "Correction equations to estimate body fat with plicometer WCS dual hand". Research on Biomedical Engineering. 33 (4): 285–292. doi:10.1590/2446-4740.01117. In this paper the terms "skinfold caliper" and "plicometer" are used interchangeable, as in the description of Table 2

- ↑ Sarría A, García-Llop LA, Moreno LA, Fleta J, Morellón MP, Bueno M (August 1998). "Skinfold thickness measurements are better predictors of body fat percentage than body mass index in male Spanish children and adolescents". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 52 (8): 573–576. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600606. PMID 9725657.

- ↑ Bruner R (2 November 2001). "A–Z of health, fitness and nutrition". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ↑ Heymsfield S (2005). Human Body Composition. Human Kinetics. pp. 425–. ISBN 978-0-7360-4655-8.

- ↑ Pineau JC, Guihard-Costa AM, Bocquet M (2007). "Validation of ultrasound techniques applied to body fat measurement. A comparison between ultrasound techniques, air displacement plethysmography and bioelectrical impedance vs. dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry". Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. 51 (5): 421–427. doi:10.1159/000111161. PMID 18025814. S2CID 24424682.

- ↑ Utter AC, Hager ME (May 2008). "Evaluation of ultrasound in assessing body composition of high school wrestlers". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 40 (5): 943–949. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318163f29e. PMID 18408602.

- ↑ "B–3" (PDF). Army Regulation 600–9: The Army Body Composition Program. Department of the Army. 28 June 2013. pp. 26–31. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

Description of circumference sites and their anatomical landmarks and technique

- ↑ "Gastric Banding Surgery". UC San Diego. Archived from the original on 2011-04-15. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- ↑ BMI to body fat percentage formula Archived 2014-11-01 at the Wayback Machine, Deurenberg P, Weststrate JA, Seidell JC (March 1991). "Body mass index as a measure of body fatness: age- and sex-specific prediction formulas". The British Journal of Nutrition. 65 (2): 105–114. doi:10.1079/BJN19910073. PMID 2043597.

- ↑ How to Convert BMI to Body Fat Percentage Archived 2022-03-26 at the Wayback Machine. By Jessica Bruso with reference to a study published in the International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders in 2002. July 18, 2017.

- ↑ Barreira TV, Harrington DM, Staiano AE, Heymsfield SB, Katzmarzyk PT (August 2011). "Body adiposity index, body mass index, and body fat in white and black adults". JAMA. 306 (8): 828–830. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1189. PMC 3951848. PMID 21862743.

External links

- Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Heo M, Jebb SA, Murgatroyd PR, Sakamoto Y (September 2000). "Healthy percentage body fat ranges: an approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 72 (3): 694–701. doi:10.1093/ajcn/72.3.694. PMID 10966886.