Cardioversion

| Cardioversion | |

|---|---|

| |

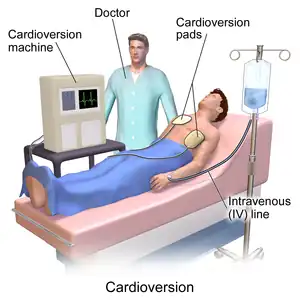

| Illustration of cardioversion | |

| Specialty | Cariology |

| Types | Electrical; pharmacologic |

Cardioversion is a procedure by which an abnormally fast heart rate or other heart arrhythmias are converted to a normal rhythm. It can be done with electricity or medications. Synchronized electrical cardioversion uses electric current to the heart at a specific moment in the cardiac cycle, restoring the activity of the electrical conduction system of the heart. (Defibrillation uses a therapeutic dose of electric current to the heart at a random moment in the cardiac cycle, and is the most effective resuscitation measure for cardiac arrest associated with ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia.[1]) Pharmacologic cardioversion, also called chemical cardioversion, uses antiarrhythmia medication instead of an electrical shock.[2]

Electrical

To perform synchronized electrical cardioversion, two electrode pads are used (or, alternatively, the traditional hand-held "paddles"), each comprising a metallic plate which is faced with a saline based conductive gel. The pads are placed on the chest of the patient, or one is placed on the chest and one on the back. These are connected by cables to a machine which has the combined functions of an ECG display screen and the electrical function of a defibrillator. A synchronizing function (either manually operated or automatic) allows the cardioverter to deliver a reversion shock, by way of the pads, of a selected amount of electric current over a predefined number of milliseconds at the optimal moment in the cardiac cycle which corresponds to the R wave of the QRS complex on the ECG. Timing the shock to the R wave prevents the delivery of the shock during the vulnerable period (or relative refractory period) of the cardiac cycle, which could induce ventricular fibrillation. If the patient is conscious, various drugs are often used to help sedate the patient and make the procedure more tolerable. However, if the patient is hemodynamically unstable or unconscious, the shock is given immediately upon confirmation of the arrhythmia. When synchronized electrical cardioversion is performed as an elective procedure, the shocks can be performed in conjunction with drug therapy until sinus rhythm is attained. After the procedure, the patient is monitored to ensure stability of the sinus rhythm.

Synchronized electrical cardioversion is used to treat hemodynamically unstable supraventricular (or narrow complex) tachycardias, including atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. It is also used in the emergent treatment of wide complex tachycardias, including ventricular tachycardia, when a pulse is present. Pulseless ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation are treated with unsynchronized shocks referred to as defibrillation. Electrical therapy is inappropriate for sinus tachycardia, which should always be a part of the differential diagnosis.

Recommended energy

- For atrial fibrillation, 120 to 200 joules for biphasic devices and 360 joules for monophasic devices

- For narrow regular rhythms (atrial flutter and SVT), 50 to 100 joules for biphasic devices and 100 joules for monophasic devices

- For ventricular tachycardia with a pulse, 100 joules for biphasic devices and 200 joules for monophasic devices

- For ventricular fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia, 120–200 joules for biphasic devices and 360 joules for monophasic devices[3][4][5]

Medication

Various antiarrhythmic agents can be used to return the heart to normal sinus rhythm.[6] Pharmacological cardioversion is an especially good option in patients with fibrillation of recent onset. Drugs that are effective at maintaining normal rhythm after electric cardioversion can also be used for pharmacological cardioversion. Drugs like amiodarone, diltiazem, verapamil and metoprolol are frequently given before cardioversion to decrease the heart rate, stabilize the patient and increase the chance that cardioversion is successful. There are various classes of agents that are most effective for pharmacological cardioversion.

Class I agents are sodium (Na) channel blockers (which slow conduction by blocking the Na+ channel) and are divided into 3 subclasses a, b and c. Class Ia slows phase 0 depolarization in the ventricles and increases the absolute refractory period. Procainamide, quinidine and disopyramide are Class Ia agents. Class 1b drugs lengthen phase 3 repolarization. They include lidocaine, mexiletine and phenytoin. Class Ic greatly slow phase 0 depolarization in the ventricles (however unlike 1a have no effect on the refractory period). Flecainide, moricizine and propafenone are Class Ic agents.

Class II agents are beta blockers which inhibit SA and AV node depolarization and slow heart rate. They also decrease cardiac oxygen demand and can prevent cardiac remodeling. Not all beta blockers are the same; some are cardio selective (affecting only beta 1 receptors) while others are non-selective (affecting beta 1 and 2 receptors). Beta blockers that target the beta-1 receptor are called cardio selective because beta-1 is responsible for increasing heart rate; hence a beta blocker will slow the heart rate.

Class III agents (prolong repolarization by blocking outward K+ current): amiodarone and sotalol are effective class III agents. Ibutilide is another Class III agent but has a different mechanism of action (acts to promote influx of sodium through slow-sodium channels). It has been shown to be effective in acute cardioversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter.

Class IV drugs are calcium (Ca) channel blockers. They work by inhibiting the action potential of the SA and AV nodes.

If the patient is stable, adenosine may be administered first, as the medicine performs a sort of "chemical cardioversion" and may stabilize the heart and let it resume normal function on its own without using electricity.

See also

References

- ↑ Marino, Paul L. (2014). Marino's the ICU book (Fourth ed.). ISBN 978-1451121186.

- ↑ Shea, Julie B.; William H. Maisel (2002). "Cardioversion". Circulation. 106 (22): e176–78. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000040586.24302.B9. PMID 12451016. Archived from the original on 2010-01-15. Retrieved 2009-09-22.

- ↑ Fuster, V; Rydén, LE; Cannom, DS; Crijns, HJ; Curtis, AB; Ellenbogen, KA; Halperin, JL; Le Heuzey, JY; Kay, GN; Lowe, JE; Olsson, SB; Prystowsky, EN; Tamargo, JL; Wann, S; Smith SC, Jr; Jacobs, AK; Adams, CD; Anderson, JL; Antman, EM; Halperin, JL; Hunt, SA; Nishimura, R; Ornato, JP; Page, RL; Riegel, B; Priori, SG; Blanc, JJ; Budaj, A; Camm, AJ; Dean, V; Deckers, JW; Despres, C; Dickstein, K; Lekakis, J; McGregor, K; Metra, M; Morais, J; Osterspey, A; Tamargo, JL; Zamorano, JL; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice, Guidelines; European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice, Guidelines; European Heart Rhythm, Association; Heart Rhythm, Society (Aug 15, 2006). "ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society". Circulation. 114 (7): e257–354. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.106.177292. PMID 16908781.

- ↑ Zipes, DP; Camm, AJ; Borggrefe, M; Buxton, AE; Chaitman, B; Fromer, M; Gregoratos, G; Klein, G; Moss, AJ; Myerburg, RJ; Priori, SG; Quinones, MA; Roden, DM; Silka, MJ; Tracy, C; Smith SC, Jr; Jacobs, AK; Adams, CD; Antman, EM; Anderson, JL; Hunt, SA; Halperin, JL; Nishimura, R; Ornato, JP; Page, RL; Riegel, B; Blanc, JJ; Budaj, A; Dean, V; Deckers, JW; Despres, C; Dickstein, K; Lekakis, J; McGregor, K; Metra, M; Morais, J; Osterspey, A; Tamargo, JL; Zamorano, JL; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task, Force; European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice, Guidelines; European Heart Rhythm, Association; Heart Rhythm, Society (Sep 5, 2006). "ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society". Circulation. 114 (10): e385–484. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.178233. PMID 16935995.

- ↑ Link, MS; Atkins, DL; Passman, RS; Halperin, HR; Samson, RA; White, RD; Cudnik, MT; Berg, MD; Kudenchuk, PJ; Kerber, RE (Nov 2, 2010). "Part 6: electrical therapies: automated external defibrillators, defibrillation, cardioversion, and pacing: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S706–19. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970954. PMID 20956222.

- ↑ "Medications for Arrhythmia". American Heart Association. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 13 Sep 2020.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Cardioversion from the National Institutes of Health Archived 2016-07-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Pharmacological Cardioversion from the American Academy of Family Physicians (1998)

- Synchronized Electrical Cardioversion from eMedicine Online

- Cardioversion from the Heart Rhythm Society Archived 2010-11-29 at the Wayback Machine