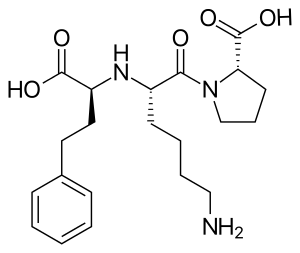

Lisinopril

| |

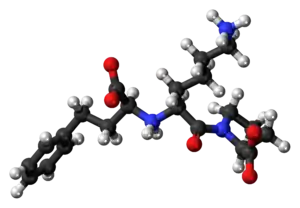

Chemical structure of lisinopril | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /laɪˈsɪnəprɪl/, ly-SIN-ə-pril |

| Trade names | Prinivil,[1] Zestril,[2] Qbrelis,[3] others[4] |

| Other names | (2S)-1-[(2S)-6-amino-2-{[(1S)-1-carboxy-3-phenylpropyl]amino}hexanoyl]pyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | ACE inhibitor |

| Main uses | High blood pressure, heart failure, heart attacks[5] |

| Side effects | Headache, dizziness, feeling tired, cough, nausea, rash[5] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 10 mg[7] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a692051 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | approx. 25%, but wide range between individuals (6 to 60%) |

| Protein binding | 0 |

| Metabolism | None |

| Elimination half-life | 12 hours[9] |

| Excretion | Eliminated unchanged in urine |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H31N3O5 |

| Molar mass | 405.495 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Lisinopril is a medication of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor class used to treat high blood pressure, heart failure, and after heart attacks.[5] For high blood pressure it is usually a first line treatment, although in black people calcium-channel blockers or thiazide diuretics work better.[5] It is also used to prevent kidney problems in people with diabetes.[5] Lisinopril is taken by mouth.[5] Full effect may take up to four weeks to occur.[5]

Common side effects include headache, dizziness, feeling tired, cough, nausea, and rash.[5] Serious side effects may include low blood pressure, liver problems, high blood potassium, and angioedema.[5] Use is not recommended during the entire duration of pregnancy as it may harm the baby.[5] Lisinopril works by inhibiting the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system.[9]

Lisinopril was patented in 1978, and approved for medical use in the United States in 1987.[5][10] It is available as a generic medication.[5] In the United States the wholesale cost per month was less than US$0.70 as of 2018.[11] In the United Kingdom it cost the NHS about ₤10 per month as of 2018.[12] In 2017, it was the most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 104 million prescriptions.[13][14] In July 2016, an oral solution formulation of lisinopril was approved for use in the United States.[5][15]

Medical uses

Lisinopril is typically used for the treatment of high blood pressure, congestive heart failure, acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), and diabetic nephropathy.[5][1]

A review concluded that lisinopril was effective for treatment of proteinuric kidney disease, including diabetic proteinuria.[16]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 10 mg by mouth.[7]

The dose must be adjusted in those with poor kidney function. Dose adjustments may be required when creatinine clearance is less than or equal to 30mL/min.[1] Since lisinopril is removed by dialysis, dosing changes must also be considered for people on dialysis.[1]

Contraindications

Lisinopril is contraindicated in people who have a history of angioedema (hereditary or idiopathic) or who have diabetes and are taking aliskiren.[1]

Side effects

Rates of side effects vary according to which disease is being treated for.[1]

People taking lisinopril for the treatment of hypertension may experience the following side effects:[1]

- Headache (3.8%)

- Dizziness (3.5%)

- Cough (2.5%) Persons with the ACE I/D genetic polymorphism may be at higher risk for ACE inhibitor-associated cough.[17]

- Difficulty swallowing or breathing (signs of angioedema), allergic reaction (anaphylaxis)

- Hyperkalemia (2.2% in adult clinical trials)

- Fatigue (1% or more)

- Diarrhea (1% or more)

- Some severe skin reactions have been reported rarely, including toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome; causal relationship has not been established.

People taking lisinopril for the treatment of myocardial infarction may experience the following side effects:[1]

- Hypotension (5.3%)

- Kidney dysfunction (1.3%)

People taking lisinopril for the treatment of heart failure may experience the following side effects:[1]

- Hypotension (3.8%)

- Dizziness (12% at low dose – 19% at high dose)

- Chest pain (2.1%)

- Fainting (5–7%)

- Hyperkalemia (3.5% at low dose – 6.4% at high dose)

- Difficulty swallowing or breathing (signs of angioedema), allergic reaction (anaphylaxis)

- Fatigue (1% or more)

- Diarrhea (1% or more)

- Some severe skin reactions have been reported rarely, including toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome; a causal relationship has not been established.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Animal and human data have revealed evidence of lethal harm to the embryo and teratogenicity associated with ACE inhibitors. No controlled data in human pregnancy are available. Birth defects have been associated with use of lisinopril in any trimester. However, there have been reports of death and increased toxicity to the fetus and newly born child with the use of lisinopril in the second and third trimesters. The label states, "When pregnancy is detected, discontinue Zestril as soon as possible." The manufacturer recommends mothers should not breastfeed while taking this medication because of the current lack of safety data.[1]

Overdose

In one reported overdose, the half-life of lisinopril was prolonged to 14.9 hours.[18] The case report of the event estimates that the individual consumed between 420 and 500 mg of lisinopril and survived.[19] In cases of overdosage, it can be removed from circulation by dialysis.[1]

Interactions

- Dental care

ACE-inhibitors like lisinopril are considered to be generally safe for people undergoing routine dental care, though the use of lisinopril prior to dental surgery is more controversial, with some dentists recommending discontinuation the morning of the procedure.[20] People may present to dental care suspicious of an infected tooth, but the swelling around the mouth may be due to lisinopril-induced angioedema, prompting emergency, and medical referral.[20]

Pharmacology

Lisinopril is the lysine-analog of enalapril. Unlike other ACE inhibitors, it is not a prodrug, is not metabolized by the liver, and is excreted unchanged in the urine.[1]

Mechanism of action

Lisinopril is an ACE inhibitor, meaning it blocks the actions of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) in the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), preventing angiotensin I from being converted to angiotensin II. Angiotensin II is a potent direct vasoconstrictor and a stimulator of aldosterone release. Reduction in the amount of angiotensin II results in relaxation of the arterioles. Reduction in the amount of angiotensin II also reduces the release of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex, which allows the kidney to excrete sodium along with water into the urine, and increases retention of potassium ions.[9] Specifically, this process occurs in the peritubular capillaries of the kidneys in response to a change in Starling forces.[21] The inhibition of the RAAS system causes an overall decrease in blood pressure.[9]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Lisinopril has a poor bioavailability of ~25% (reduced to 16% in people with New York Heart Association Functional Classification (NYHA) Class II–IV heart failure).[1][9] Its time to peak concentration is 7 hours.[1][9] The peak effect of lisinopril is about 4 to 8 hours after administration.[22] Food does not affect its absorption.[22]

Distribution

Lisinopril does not bind to proteins in the blood.[1][9] It does not distribute as well in people with NYHA Class II–IV heart failure.[1][9]

Metabolism

Lisinopril is the only water-soluble member of the ACE inhibitor class, with no metabolism by the liver.[22]

Elimination

Lisinopril leaves the body completely unchanged in the urine.[1][9] The half-life of lisinopril is 12 hours, and is increased in people with kidney problems.[1][9] While the plasma half-life of lisinopril has been estimated between 12–13 hours, the elimination half-life is much longer, at around 30 hours.[22] The full duration of action is between 24 and 30 hours.[22]

Chemistry

Pure lisinopril powder is white to off white in color.[1] Lisinopril is soluble in water (approximately 13 mg/L at room temperature),[23] less soluble in methanol, and virtually insoluble in ethanol.[1]

History

Captopril, the first ACE inhibitor, is a functional and structural analog of a peptide derived from the venom of the jararaca, a Brazilian pit viper (Bothrops jararaca).[24] Enalapril is a derivative, designed by scientists at Merck to overcome the rash and bad taste caused by captopril.[25][26]: 12–13 Enalapril is actually a prodrug; the active metabolite is enalaprilat.[27]

Lisinopril is a synthetic peptide derivative of captopril.[23] Scientists at Merck created lisinopril by systematically altering each structural unit of enalaprilat, substituting various amino acids. Adding lysine at one end of the drug turned out to have strong activity and had adequate bioavailability when given orally; analogs of that compound resulted in lisinopril, which takes its name from the discovery with lysine. Merck conducted clinical trials, and the drug was approved for hypertension in 1987 and congestive heart failure in 1993.[27]

The discovery posed a problem, since sales of enalapril were strong for Merck, and the company did not want to diminish those sales. Merck ended up entering into an agreement with Zeneca under which Zeneca received the right to co-market lisinopril, and Merck received the exclusive rights to an earlier stage aldose reductase inhibitor drug candidate, a potential treatment for diabetes. Zeneca's marketing and brand name, "Zestril", turned out to be stronger than Merck's effort.[28] The drug became a blockbuster for Astrazeneca (formed in 1998), with annual sales in 1999 of $1.2B.[29]

The US patents expired in 2002.[29] Since then, lisinopril has been available under many brand names worldwide; some formulations include the diuretic hydrochlorothiazide.[4]

Society and culture

Cost

In the United States the wholesale cost per month was less than US$0.70 as of 2018.[11] In the United Kingdom it cost the NHS about ₤10 per month as of 2018.[12] In 2017, it was the most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 104 million prescriptions.[13][14]

.svg.png.webp) Lisinopril costs (US)

Lisinopril costs (US).svg.png.webp) Lisinopril prescriptions (US)

Lisinopril prescriptions (US)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 "Prinivil- lisinopril tablet". DailyMed. 4 November 2019. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- 1 2 "Zestril- lisinopril tablet". DailyMed. 31 October 2019. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- 1 2 "Qbrelis- lisinopril solution". DailyMed. 31 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- 1 2 "Lisinopril". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Lisinopril Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 12 November 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Lisinopril Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 22 October 2019. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ "Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) – (emc)". Lisinopril 10mg Tablet. 13 November 2019. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Benowitz, Neal L. (2020). "11. Antihypertensive agents". In Katzung, Bertram G.; Trevor, Anthony J. (eds.). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 183–185. ISBN 978-1-260-45231-0. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 467. ISBN 978-3527607495. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- 1 2 "NADAC as of 2018-12-19". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- 1 2 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 170. ISBN 9780857113382.

- 1 2 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- 1 2 "Lisinopril – Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. 23 December 2019. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ↑ "Drug Approval Package: Qbrelis (lisinopril)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 July 2016. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ↑ Sadat-Ebrahimi SR, Parnianfard N, Vahed N, Babaei H, Ghojazadeh M, Tang S, Azarpazhooh A (July 2018). "An evidence-based systematic review of the off-label uses of lisinopril". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 84 (11): 2502–21. doi:10.1111/bcp.13705. PMC 6177695. PMID 29971804.

- ↑ Mu G, Xiang Q, Zhou S, Xie Q, Liu Z, Zhang Z, Cui Y (January 2019). "Association between genetic polymorphisms and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Pharmacogenomics. 20 (3): 189–212. doi:10.2217/pgs-2018-0157. PMID 30672376.

- ↑ "HSDB: LISINOPRIL". toxnet.nlm.nih.gov. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ Dawson, AH; Harvey, D; Smith, AJ; Taylor, M; Whyte, IM; Johnson, CI; Cubela, RB; Roberts, MJ (24 February 1990). "Lisinopril overdose". Lancet. 335 (8687): 487–88. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)90731-j. PMID 1968218.

- 1 2 Weinstock, Robert; Johnson, Michael (2016). "Review of Top 10 Prescribed Drugs and Their Interaction with Dental Treatment". Dental Clinics of North America. 60 (2): 421–34. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2015.11.005. PMID 27040293.

- ↑ Reddi, Alluru (2018). "Disorders of ECF Volume: Nephrotic Syndrome". Fluid, Electrolyte and Acid-Base Disorders. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-60167-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Khan, M. Gabriel (2015). "Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers". Cardiac Drug Therapy. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-61779-962-4.

- 1 2 "Lisinopril". PubChem. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ Patlak M (March 2004). "From viper's venom to drug design: treating hypertension". FASEB J. 18 (3): 421. doi:10.1096/fj.03-1398bkt. PMID 15003987.

- ↑ Jenny Bryan for The Pharmaceutical Journal, 17 Apr 2009 "From snake venom to ACE inhibitor – the discovery and rise of captopril" Archived 26 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Jie Jack Li, "History of Drug Discovery". Chapter 1 in Drug Discovery: Practices, Processes, and Perspectives. Eds. Jie Jack Li, E. J. Corey. John Wiley & Sons, 2013 ISBN 978-1118354469

- 1 2 Menard J and Patchett A. "Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors". pp. 14–76 in Drug Discovery and Design. Volume 56 of Advances in Protein Chemistry. Eds. Richards FM, Eisenberg DS, and Kim PS. Series Ed. Scolnick EM. Academic Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0080493381. pp. 30–33 Archived 10 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ David R. Glover. Vie D'or: Memoirs of a Pharmaceutical Physician. Troubador Publishing Ltd, 2016. ISBN 978-1785894947. Merck Sharp and Dohme: lisinopril section Archived 11 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Express Scripts. Patent expirations Archived 10 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Fogari R, Zoppi A, Corradi L, Lazzari P, Mugellini A, Lusardi P (November 1998). "Comparative effects of lisinopril and losartan on insulin sensitivity in the treatment of non diabetic hypertensive patients". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 46 (5): 467–71. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00811.x. PMC 1873694. PMID 9833600.

- Bussien JP, Waeber B, Nussberger J, Gomez HJ, Brunner HR (1985). "Once-daily lisinopril in hypertensive patients: Effect on blood pressure and the renin–angiotensin system". Curr Therap Res. 37: 342–51.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "Lisinopril". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.