This article was co-authored by Clinton M. Sandvick, JD, PhD. Clinton M. Sandvick worked as a civil litigator in California for over 7 years. He received his JD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1998 and his PhD in American History from the University of Oregon in 2013.

There are 26 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, 89% of readers who voted found the article helpful, earning it our reader-approved status.

This article has been viewed 46,519 times.

An executor of a will is the person tasked to handle a deceased person's final wishes, whether it be financial distribution or property transfers. The executor is also in charge of making sure all debts incurred by the deceased are paid from the estate prior to the beneficiaries receiving their portion. As the executor, you will be in charge of handling the estate as it goes through probate, which is the official mechanism for transferring property from the decedent to surviving beneficiaries. Probate happens with or without a will.

Steps

Being Appointed Executor

-

1Check if you are eligible. Though executors are often named in wills, sometimes no executor is named. In this situation, individuals will apply to become the executor. States have different rules regarding who may be appointed executor of an estate. However, most states require that the executor be legally capable of handling his or her own affairs and be at least the age of majority (typically 18).

- Additionally, some states may require that you be a citizen of the state.

- Most states also prohibit felons from acting as executors.[1]

-

2Request appointment. If you are eligible, contact the probate court by phone or in person and request the form necessary for appointment as executor from the clerk of court.[2]

- Forms are often posted online at the court’s website.

- Forms vary from state to state, so be sure that you are filling out your state’s form.

- Alternately, if the will appoints you as executor and you wish to decline the position, then you can renounce the position by filing a petition with the court. You should ask the court clerk for the form.

Advertisement -

3Complete the form. Follow all instructions when completing the form. Avoid making these mistakes:

- not correctly notating the full name of the deceased

- not notarizing the form

- incorrectly completing the information asked for

-

4Present a copy of the application to the probate court. Make the correct number of copies, including one for yourself. Take the application to the clerk’s office. No appointment should be necessary.

- You will probably have to pay a filing fee.[3] Call ahead of time to ask the amount of the fee and acceptable methods of payment.

-

5Notify other beneficiaries. You typically must inform the other beneficiaries that you are applying to be the executor.[4] You can notify them by completing a “Notice of Application” form, which should be available from the court clerk.

-

6Obtain a surety bond, if required. Some states require that the proposed executor post a surety bond. A surety bond is insurance against wrongdoing. Should the executor make a mistake, the insurer will compensate the beneficiaries. The bond can often be paid by estate assets.[5]

- Sometimes, if the decedent stated in the will that the executor does not need a bond, then the bond can be waived.

- To obtain a surety bond, search online for a company that provides bonds in your area. You may also check with the court clerk. The clerk may have a list of reputable companies.

- The bond company will want to look at your credit history and possibly run a background check.[6]

-

7Attend the appointment hearing. The court will schedule a hearing to give interested parties a chance to object to the appointment. Usually, the hearing is a formality and no one objects to the executor’s appointment.

- If someone challenges your appointment, then the court will hold a hearing. At the hearing, each side will argue why they should be appointed executor. If you are being challenged, you should contact an attorney.

- In some states, the hearing can also be dispensed with if all interested parties (i.e., those who would inherit property) sign waivers.[7]

-

8Get the “Letters of Administration.” Once the court approves an executor, that person gets “Letters of Administration”[8] or “Letters Testamentary.”[9] These letters allow the executor to act on behalf of the estate.

- If you find that you no longer want to continue as the executor, then you should file a petition with the court, stating your reasons. If the court finds that you have “good cause,” then a successor executor will be named. Often, the successor executor is identified in the will. If not, the court will hold a hearing and consider other family members.[10]

Preparing for Probate

-

1Come up with a filing system. Because executors handle a lot of paper, you should establish a filing system upfront. This will help you not waste time looking for things.

- To create an effective filing system you should think about how you want to categorize documents.[11] For executors, common categories will be: money owed by debtors, money owed to creditors, tax issues, court forms, and estate expenses. You will then create binders or hanging files for each of these categories.

- Once you have categories, you can then create sub categories.[12] For example, under “Money owed to Creditors,” you can then sub-categorize based on the entity money was owed to: to a mortgage company, to an auto lender, to credit card companies, etc. Each of these sub-categories can then get an individual manila envelope in which you keep copies of bills, correspondence, or notes.

- Adjust your filing system to suit your needs as the probate process unfolds.

-

2Find the will. If the decedent had a will, then try to find it. Search for wills in filing cabinets, desk drawers, and safety deposit boxes. Also ask the decedent’s lawyer, who may have kept the will.

- If you can’t find the will, you will have to proceed through probate using your state’s intestacy laws. Intestacy laws provide the default rules for how the estate should be distributed. Speak to an attorney about this.

- In some states, the person who has the will (the “custodian”) must take the will to the probate court or to the executor within 30 days (or less) of the decedent’s death. Failure to do this could result in the custodian being sued for damages.[13]

-

3Order a copy of the death certificate. You will need a number of official death certificates to serve as evidence of the death. The mortuary that handles the decedent’s funeral arrangements usually arranges for some certified death certificates. You should ask for at least 10.

- For more information on how to get copies of death certificates, visit wikiHow’s How to Acquire a Death Certificate.

-

4Hire an attorney. It is extremely important to hire an attorney.[14] Some states, like Florida, require an attorney to go through regular probate.[15] In other states, you are strongly encouraged to have a lawyer, who can help you navigate the probate process and keep you from making mistakes. To find a probate attorney, contact your state’s bar association, which should run a referral service. When choosing an attorney, consider:

- Location. It is usually best to choose an attorney who practices in the state where the decedent lived. This person will have familiarity with the relevant estate laws and probate procedure.

- Expertise. Choose an attorney who specializes in probate work. Additionally, if the estate is particularly large, then choose an attorney who has experience in the particular type of estate that you will probate. For example, if you are dealing with complex trust instruments, then you may need to hire someone who is a trust expert.

- Personality. As the executor, you will be in frequent contact with the attorney. You should choose someone who you trust and like personally.

-

5Hire an accountant. Hiring an accountant to manage estate funds ensures that the funds are handled correctly, which simplifies your job. Though not absolutely required, an accountant can make paying debts easy. An accountant also calculates and files the estate’s tax bills, which are often complicated.[16]

- Consider hiring a Certified Public Accountant (CPA). A CPA often has more experience or education than a regular accountant.

- You should compare rates for accountants.[17] Get an estimate from an accountant and then compare it to the rates offered by other CPAs in the area.

-

6Hire a financial planner. You might want to consider hiring a financial planner, who can help you deal with the decedent’s accounts. Also, a financial planner can tell you how to close down accounts, cash them out, transfer them, or how to reinvest them.[18]

- Anyone can use the title “financial planner.”[19] You therefore need to gather recommendations. If you hire an attorney first, then the attorney can probably find you a reputable financial planner.

Notifying Organizations of the Testator’s Passing

-

1Contact the Social Security Administration (SSA). If the decedent was receiving benefits from SSA, then contact the agency. You must contact them as soon as possible. If benefits are paid in error, then SSA will make you refund them, which can be a long and complicated process.[20]

- Notify SSA over the phone or at a local SSA office. To find the office nearest you, use this office locator.

- Be sure to have a copy of the death certificate with you to present to SSA.

- Also contact Medicaid, if applicable.

-

2Notify creditors. Normally, a decedent carries some form of debt, whether everyday bills or a mortgage. As the executor, you need to make a good faith effort to find creditors.[21]

- Your attorney should also help you post notice in appropriate newspapers. This notice is necessary to allow creditors to come forward and make a claim against the estate for the amount of money they are owed.[22]

- If a creditor does not step forward within the time specified by your state’s probate laws, then the estate cannot be charged for the debt.

-

3Contact debtors. You also need to inform those who owed the decedent money that they should make payment to the estate. Be sure to send debtors a letter to this effect, and keep copies on file.[23]

- Also check with your attorney to find out how long debtors have to pay the debts they owe the estate. Be sure to include this information in the letter you send.

-

4Notify credit card companies. You will need to notify credit card companies that the decedent has passed. They will then close the accounts. After the accounts have been closed, you should destroy the credit cards.[24]

- The credit card companies will later make a claim on the estate. You should pay them off when you pay off all of the estate’s debts, before distribution of assets to beneficiaries.

-

5Notify pension providers. If the decedent was eligible for a pension, then you should notify the pension administrator. Sometimes, pension payments end on death, while in other situations a lump sum may be owed.

-

6Contact banks. Write or call any bank that the decedent did business with. You will probably have to provide a copy of the certified death certificate as well as copies of your Letters of Administration or Letters Testamentary, especially if the decedent still has money in the accounts.

-

7Contact insurance companies. Provide proper notification to any insurance company of the decedent’s death. This will insure the timely payment of funds to beneficiaries. Look through the decedent’s papers to see what life insurance policies he or she had.

- Also, you should contact other insurers so that payments can be halted. Common insurance policies include car, homeowner’s, dental, and health. Stopping those payments will save the estate money.

Probating the Estate

-

1Identify estate assets. Before you can choose a method of estate administration, you need to locate assets owned by the decedent.[25] Doing so will give you some idea of the size of the estate. Note, however, that not all property owned by the decedent is part of the estate. The following is typically excluded:

- life insurance

- pensions

- healthcare savings accounts

- property held in joint tenancy

- joint/survivor bank accounts

- POD (Payable on Death) bank accounts

- assets in certain types of trusts

-

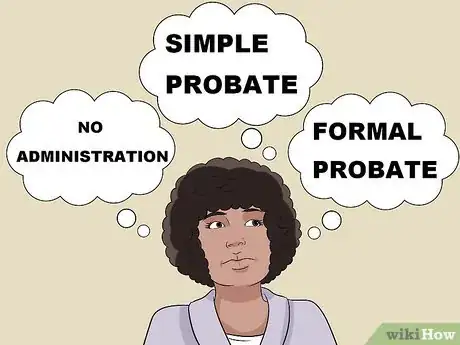

2Choose a method of administration. Once you have a general idea of the size of the estate, you should choose a method of administration. States offer many different kinds of administration.[26]

- No administration. If the estate is small enough, most states allow the property to be distributed without going through probate. The size requirements vary. In Florida, you can avoid probate altogether if the assets are exempt from creditor claims or are sufficient to only cover funeral expenses.[27] In California, you can avoid probate if the estate is valued at no more than $150,000 or property is valued at no more than $50,000. In this situation, property may be claimed by affidavit.[28]

- “Simple” or “summary” probate. Most states also offer an informal probate procedure called “summary administration” or “simple” probate. To be eligible, the estate must be smaller than a certain amount. For example, in California an estate cannot be worth more than $150,000. In Florida, the maximum is $75,000.[29]

- Formal probate. This is the best option for more complicated estates. It may also be the only option for estates that are too large to qualify for summary administration.

-

3Prove that the will is valid. If there is a will, then you must prove that the will is valid. Usually, to prove the validity of a will, all you need is a statement to that effect from one or more of the witnesses who signed the will. Courts allow different kinds of statements:[30]

- A “self-proving affidavit” that was signed by the witness in front of a notary when the will was signed.

- A sworn statement signed by the witness at the time probate is opened.

- A statement by the witness made in court.

-

4Present other evidence of the will’s validity. If the witnesses to the will are no longer living, or cannot be found, then other evidence may be needed to prove that the will is valid. Your attorney will help you identify what kinds of evidence the court will accept. For example, courts will scrutinize the signature on the will and accept testimony from people familiar with the decedent’s signature in order to try and validate a will.[31]

-

5Collect the estate property. If estate property is in the hands of other people, then you need to collect it. You also have the duty as the executor to keep all property safe.[32]

-

6Appraise the estate. As executor, you need to figure out the value of the probate assets. This could potentially require that you hire an appraiser.

- To find an appraiser, search online. Type your city or county and “appraiser” into a web browser. Alternately, you could search the Yellow Pages.

-

7Create an inventory of all estate property. This worksheet will list all of the decedent’s property and their corresponding values. An example of an inventory is available here.

- Also create an inventory of non-probate assets. You will want to know the value of the non-probate assets as well in case you are trying to divide up assets evenly between beneficiaries.

-

8Determine which beneficiaries will get specific assets. The decedent’s will typically specifies what each beneficiary will receive: specific assets, money, or a percentage of the estate. Nevertheless, wills vary greatly in terms of how detailed they are in allocating property.

- This is often a source of conflict. As the executor, you must proceed with great care.[33]

- Keep lines of communication open. Talk to all family members to find out who is interested in what property. A typical will does not name a beneficiary for each specific piece of personal property owned by the decedent. Accordingly, you will have to decide who gets what.

- If more than one person is interested in the same piece of property, and that piece of property is not given to anyone in the will, then you can hold a “family auction.” At the auction, all assets are given a monetary value and the names of beneficiaries are pulled out of a hat. People then choose a piece of property. The value of each object they claim is then deducted from what they would receive from the estate.

-

9Open an estate bank account. You should set up an estate checking account and pay all debts from this account. Open it in the name of the estate. Using one account will make it easier to track money coming in and going out.

- Get a taxpayer ID. To open a bank account, you will need an ID number. You can apply online at www.irs.gov. You also must complete IRS Form SS-4.

- You can also call the IRS and request a tax ID number. If you do this, then you will fill out Form SS-4 and mail it in afterwards.

- Make sure all debts owed to the estate are paid into the account as well.

- Be sure never to mix estate and personal funds. You should not dip into the estate account to cover personal expenses. Use it only for the estate’s expenses.

-

10Liquidate remaining estate property. If property is not specifically given to a beneficiary, and no one wants the actual item, then you will need to liquidate the property and distribute the proceeds to the beneficiaries.

- If real estate remains, you need to speak to a realtor. A realtor can help you get a piece of property ready to sell. Be sure to communicate with beneficiaries what the sale price will be, and listen to any recommendations they make.

- Research where you can sell personal property. For personal assets (like furniture, books, mementos, etc.), decide where it is best to sell them. If there are antiques or art, then ask the appraiser. For more every-day objects, like cookware and clothes, you can probably hold a yard sale.

-

11Pay taxes. As the executor, you are responsible for paying taxes. The most common taxes will be income tax and estate tax.[34]

-

12Pay bills. You need to pay estate debts out of the estate’s assets.[35] If the debts were small, or there was a lot of cash in the estate, then paying the debts should be easy for your accountant. Sometimes, however, you need to liquidate assets to cover debts.

- The executor pays reasonable funeral expenses first.[36]

- Your state statute will designate the order in which you pay debts and disburse estate assets. You must follow the order outlined in the statute.

-

13Get paid. You have the option of being compensated out of the estate for your work as executor (though you can also decline to get paid). Payment is set by statute and largely depends on the size of the estate. In Oregon, for example, executors are entitled to:

- 7% of the first $1,000 of the estate

- an additional 4% of any amount over $1,000 but less than $10,000

- an additional 3% of any amount above $10,000 up to $50,000

- an additional 2% of any amount over $50,000.

- Also, the executor is entitled to 1% of non-probate property, such as life insurance proceeds.[37]

-

14Deliver property to beneficiaries. Beneficiaries who were given specific pieces of property should be told when and how to collect it.[38] If you need to deliver the property, then work with the beneficiary on how to deliver the property and how to pay for its delivery.

- As a final step, you then distribute the remainder of the estate. Often, this will consist of money once the estate has been liquidated. You should work with the beneficiaries to come to an agreement about when and how this money will be distributed.

-

15Close the estate. Once all assets are distributed and all bills are paid, the estate can be closed.[39] Keep in mind that the estate is not closed until you receive the final order from the court.

- You will probably have to file a petition with the court, so it is important to involve the estate’s attorney in this process.

- Once you receive the final disposition of the estate, make sure to keep a copy, along with copies of any other relevant paperwork. Consult with your estate’s attorney and accountant as to what paperwork you need to keep from the estate and for how long you need to keep it.

- Be sure to close any bank account that was opened in the estate’s name.

Things You'll Need

- Original signed will

- Original death certificate

- Copies of death certificate

References

- ↑ http://www.rurallawcenter.org/docs/Legal%20Resource%20Guides/Being%20an%20Executor.pdf

- ↑ http://www.superiorcourt.maricopa.gov/sscDocs/packets/pbip1iz.pdf

- ↑ http://www.superiorcourt.maricopa.gov/sscDocs/packets/pbip1iz.pdf

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/executor-estate-checklist-29458.html

- ↑ http://info.legalzoom.com/surety-bond-probate-court-25890.html

- ↑ http://info.legalzoom.com/surety-bond-probate-court-25890.html

- ↑ http://www.czepigalaw.com/the-probate-process.html

- ↑ https://www.nolo.com/dictionary/letters-of-administration-term.html

- ↑ https://www.nolo.com/dictionary/letters-testamentary-term.html

- ↑ http://info.legalzoom.com/end-obligations-being-executor-will-20474.html

- ↑ http://www.smead.com/hot-topics/filing-system-1396.asp

- ↑ http://www.smead.com/hot-topics/filing-system-1396.asp

- ↑ http://www.courts.ca.gov/8865.htm

- ↑ http://www.rurallawcenter.org/docs/Legal%20Resource%20Guides/Being%20an%20Executor.pdf

- ↑ http://statewideprobate.com/estate-probate-questions/probate-faqs/

- ↑ http://executor.org/plan/hire-the-executor-team/hire-an-accountant/

- ↑ http://executor.org/plan/hire-the-executor-team/hire-an-accountant/

- ↑ http://executor.org/plan/hire-the-executor-team/hire-a-financial-planner/

- ↑ http://executor.org/plan/hire-the-executor-team/hire-a-financial-planner/

- ↑ http://executor.org/plan/notify-organizations-of-death/social-security-administration/

- ↑ http://www.rurallawcenter.org/docs/Legal%20Resource%20Guides/Being%20an%20Executor.pdf

- ↑ http://executor.org/plan/notify-organizations-of-death/file-notice-to-creditors/

- ↑ http://executor.org/plan/notify-organizations-of-death/send-notice-of-death-to-debtors/

- ↑ https://www.discover.com/credit-cards/help-center/faqs/deceased.html#q1

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/executor-estate-checklist-29458.html

- ↑ The Executor’s Guide, Mary Randolph, J.D. (Chapters 12, 17, & 18)

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/florida-probatean-overview.html

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/california-probate-shortcuts-31777.html

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/florida-probatean-overview.html

- ↑ The Executor’s Guide, Mary Randolph, J.D. (pgs. 314-316).

- ↑ http://info.legalzoom.com/prove-genuine-23824.html

- ↑ http://www.elderlawanswers.com/what-is-required-of-an-executor-6434

- ↑ http://executor.org/plan/create-a-plan-for-sale/determine-interest-among-beneficiaries-in-non-real-estate-assets/

- ↑ http://www2.nycbar.org/Publications/executor.htm#taxes

- ↑ http://www.elderlawanswers.com/what-is-required-of-an-executor-6434

- ↑ http://www.elderlawanswers.com/what-is-required-of-an-executor-6434

- ↑ http://www.hg.org/article.asp?id=22092

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/executor-estate-checklist-29458.html

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/executor-estate-checklist-29458.html