1904 United States presidential election

The 1904 United States presidential election was the 30th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 8, 1904. Incumbent Republican President Theodore Roosevelt defeated the conservative Democratic nominee, Alton B. Parker. Roosevelt's victory made him the first president who ascended to the presidency upon the death of his predecessor to win a full term in his own right. This was also the second presidential election in which both major party candidates were registered in the same home state; the others have been in 1860, 1920, 1940, 1944, and 2016.

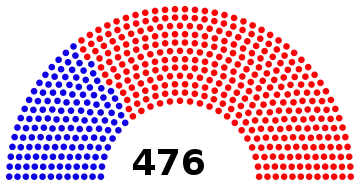

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

476 members of the Electoral College 239 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 65.5%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

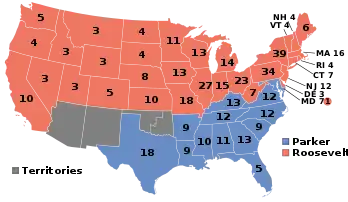

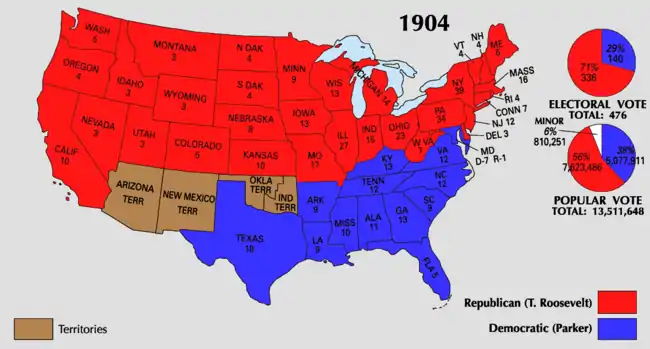

Presidential election results map. Red denotes those won by Roosevelt/Fairbanks, blue denotes states won by Parker/Davis. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Roosevelt took office in September 1901 following the assassination of his predecessor, William McKinley. After the February 1904 death of McKinley's ally, Senator Mark Hanna, Roosevelt faced little opposition at the 1904 Republican National Convention. The conservative Bourbon Democrat allies of former President Grover Cleveland temporarily regained control of the Democratic Party from the followers of William Jennings Bryan, and the 1904 Democratic National Convention nominated Alton B. Parker, Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals. Parker triumphed on the first ballot of the convention, defeating newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst.

As there was little difference between the candidates' positions, the race was largely based on their personalities; the Democrats argued the Roosevelt presidency was "arbitrary" and "erratic."[2] Republicans emphasized Roosevelt's success in foreign affairs and his record of firmness against monopolies. Roosevelt easily defeated Parker, sweeping every US region except the South, while Parker lost multiple states won by Bryan in 1900, as well as his home state of New York. Roosevelt's popular vote margin of 18.8% was the largest since James Monroe's victory in the 1820 presidential election, and would be the biggest popular vote victory in the century between 1820 and Warren Harding's 1920 landslide. With Roosevelt's landslide, he became the first presidential candidate to receive over 300 electoral votes in a presidential election. This was the first time that Missouri supported the Republican candidate since 1868.

Nominations

Republican Party nomination

Republican Party (United States) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Theodore Roosevelt | Charles W. Fairbanks | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26th President of the United States (1901–1909) |

U.S. Senator from Indiana (1897–1905) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

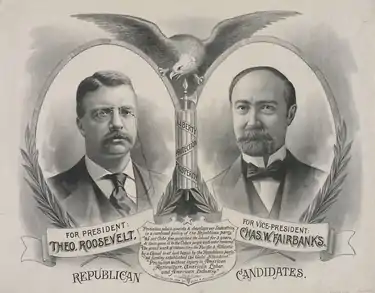

Republican candidates:

As Republicans convened in Chicago on June 21–23, 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt's nomination was assured. He had effectively maneuvered throughout 1902 and 1903 to gain control of the party to ensure it. A dump-Roosevelt movement had centered on the candidacy of conservative Senator Mark Hanna from Ohio, but Hanna's death in February 1904 had removed this obstacle. Roosevelt's nomination speech was delivered by former governor Frank S. Black of New York and seconded by Senator Albert J. Beveridge from Indiana. Roosevelt was nominated unanimously on the first ballot with 994 votes.[3]: 166

Since conservatives in the Republican Party denounced Theodore Roosevelt as a radical, they were allowed to choose the vice-presidential candidate. Senator Charles W. Fairbanks from Indiana was the obvious choice, since conservatives thought highly of him, yet he managed not to offend the party's more progressive elements. Roosevelt was far from pleased with the idea of Fairbanks for vice-president. He would have preferred Representative Robert R. Hitt from Illinois, but he did not consider the vice-presidential nomination worth a fight. With solid support from New York, Pennsylvania, and Indiana, Fairbanks was easily placed on the 1904 Republican ticket in order to appease the Old Guard.[3]: 166–167

The Republican platform insisted on maintenance of the protective tariff, called for increased foreign trade, pledged to uphold the gold standard, favored expansion of the merchant marine, promoted a strong navy, and praised in detail Roosevelt's foreign and domestic policy.[4]: 86

| Presidential ballot[3]: Appx C | |

| Ballot | 1st |

|---|---|

| Theodore Roosevelt | 994 |

| Vice-presidential ballot[3]: Appx C | |

| Ballot | 1st |

|---|---|

| Charles W. Fairbanks | 994 |

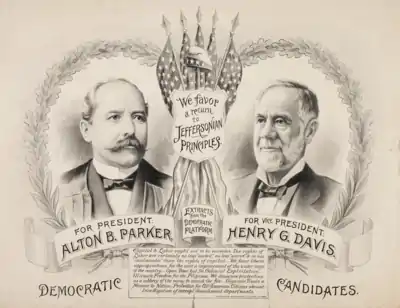

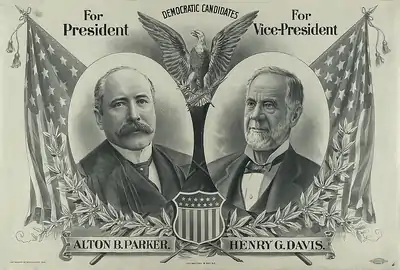

Democratic Party nomination

Democratic Party (United States) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alton B. Parker | Henry G. Davis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals (1898–1904) |

U.S. Senator from West Virginia (1871–1883) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Democratic candidates:

In 1904, both William Jennings Bryan and former President Grover Cleveland declined to run for president. Since the two Democratic nominees from the past did not seek the presidential nomination, Alton B. Parker, a Bourbon Democrat from New York, emerged as the frontrunner.

Parker was the Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals and was respected by both Democrats and Republicans in his state. On several occasions, the Republicans paid Parker the honor of running no one against him when he ran for various political positions. Parker refused to work actively for the nomination, but did nothing to restrain his conservative supporters, among them the sachems of Tammany Hall. Former President Grover Cleveland endorsed Parker.

The delegates from Florida were selected through a primary which was the first time a primary was utilized to select the delegates for a presidential convention.[6]

The Democratic Convention that met in St. Louis, Missouri, on July 6–9, 1904, has been called "one of the most exciting and sensational in the history of the Democratic Party." The struggle inside the Democratic Party over the nomination was to prove as contentious as the election itself. Though Parker, out of active politics for twenty years, had neither enemies nor errors to make him unavailable, a bitter battle was waged against Parker by the more liberal wing of the party in the months before the convention.

Despite the fact that Parker had supported Bryan in 1896 and 1900, Bryan hated him for being a Gold Democrat. Bryan wanted the weakest man nominated, one who could not take the control of the party away from him. He denounced Judge Parker as a tool of Wall Street before he was nominated and declared that no self-respecting Democrat could vote for him.

Inheriting Bryan's support was publisher, now congressman, William Randolph Hearst of New York. Hearst owned eight newspapers, all of them friendly to labor, vigorous in their trust-busting activities, fighting the cause of "the people who worked for a living." Because of this liberalism, Hearst had the Illinois delegation pledged to him and the promise of several other states. Although Hearst's newspaper was the only major publication in the East to support William Jennings Bryan and Bimetallism in 1896, he found that his support for Bryan was not reciprocated. Instead, Bryan seconded the nomination of Francis Cockrell.

The prospect of having Hearst for a candidate frightened conservative Democrats so much that they renewed their efforts to get Parker nominated on the first ballot. Parker received 658 votes on the first roll call, 9 short of the necessary two-thirds. Before the result could be announced, 21 more votes were transferred to Parker. As a result, Parker handily won the nomination on the first ballot with 679 votes to 181 for Hearst and the rest scattered.

After Parker's nomination, Bryan charged that it had been dictated by the trusts and secured by "crooked and indefensible methods." Bryan also said that labor had been betrayed in the convention and could look for nothing from the Democratic Party. Indeed, Parker was one of the judges on the New York Court of Appeals who declared the eight-hour law unconstitutional.[7]

Before a vice-presidential candidate could be nominated, Parker sprang into action when he learned that the Democratic platform pointedly omitted reference to the monetary issue. To make his position clear, Parker, after his nomination, informed the convention by letter that he supported the gold standard. The letter read, "I regard the gold standard as firmly and irrevocably established and shall act accordingly if the action of the convention today shall be ratified by the people. As the platform is silent on the subject, my view should be made known to the convention, and if it is proved to be unsatisfactory to the majority, I request you to decline the nomination for me at once, so that another may be nominated before adjournment."[8]

It was the first time a candidate had made such a move. It was an act of daring that might have lost him the nomination and made him an outcast from the party he had served and believed in all his life.[9][10]

Former Senator Henry G. Davis from West Virginia was nominated for vice president; at 80, he was the oldest major party candidate ever nominated for national office.[11] Davis received the nomination because party leaders believed that as a millionaire mine owner, railroad magnate, and banker, he could be counted on to help finance the campaign.[11] Their hopes were unrealized, as Davis did not substantially contribute to the party coffers.[11]

Parker protested against "the rule of individual caprice," the presidential "usurpation of authority," and the "aggrandizement of personal power." But his more positive proposals were so backward-looking, such as his proposal to let state legislatures and the common law develop a remedy for the trust problem, that the New York World characterized the campaign as a struggle of "conservative and constitutional Democracy against radical and arbitrary Republicanism."[12]

The Democratic platform called for reduction in government expenditures and a congressional investigation of the executive departments "already known to teem with corruption"; condemned monopolies; pledged an end to government contracts with companies violating antitrust laws; opposed imperialism; insisted upon independence for the Philippines; and opposed the protective tariff. It favored strict enforcement of the eight-hour work day; construction of a Panama Canal; the direct election of senators; statehood for the Western territories; the extermination of polygamy; reciprocal trade agreements; cuts in the army; and enforcement of the civil service laws. It condemned the Roosevelt administration in general as "spasmodic, erratic, sensational, spectacular, and arbitrary."[13]

| Presidential ballot | 1st (before shifts) | 1st (after shifts) | Unanimous | Vice-presidential ballot | 1st | Unanimous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alton B. Parker | 658 | 679 | 1,000 | Henry G. Davis | 654 | 1,000 |

| William Randolph Hearst | 200 | 181 | James R. Williams | 165 | ||

| Francis Cockrell | 42 | 42 | George Turner | 100 | ||

| Richard Olney | 38 | 38 | William Alexander Harris | 58 | ||

| Edward C. Wall | 27 | 27 | Abstaining | 23 | ||

| George Gray | 12 | 12 | ||||

| John Sharp Williams | 8 | 8 | ||||

| Robert E. Pattison | 4 | 4 | ||||

| George B. McClellan Jr. | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Nelson A. Miles | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Charles A. Towne | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Arthur Pue Gorman | 2 | - | ||||

| Bird Sim Coler | 1 | 1 |

Socialist Party nomination

The Socialist Party of America was formed from the Social Democratic Party of America and the Kangaroo faction of the Socialist Labor Party of America at a 1901 convention in Indianapolis. The Socialists received over 227,000 votes in the 1902 United States House of Representatives elections, which was twice the number of votes that Eugene V. Debs had received in 1900. Nine Socialists were elected to the city council in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in the 1904 election.[14][15]

On May 5, 1904, George D. Herron nominated Debs for the presidential nomination while Hermon F. Titus nominated Ben Hanford for the vice-presidential nomination. The 183 delegates who attended the convention voted unanimously to give the presidential and vice-presidential nominations to Debs and Hanford. Debs accepted the nomination on May 6, and chair Seymour Stedman referred to Debs as the "Ferdinand Lassalle of the twentieth century".[14][16][17]

The Socialists raised $32,700 during the campaign. Debs received 402,810 votes, which was over four times the number that he had received in 1900, and he received his largest amount of support from Illinois.[14] Debs received more votes than Parker in counties such as Rock Island in Illinois and Skamania in Washington, and outpolled Roosevelt in some Southern counties.

Continental Party

The Continental Party met in Chicago on August 31, 1904. They nominated Austin Holcomb as their presidential candidate. Initially, George H. Shibley was nominated for vice-president. He turned down the nomination, however, and A. King was nominated in his stead.[18][19]

Populist Party

The Populist Party held their national convention in Springfield, Illinois from July 4 to 6, 1904. Unsatisfied with the Democratic Party's nomination of Alton Parker for president, they chose to nominate their own candidates to contest the office. After two ballots, Thomas Watson was selected as the party's presidential candidate and Thomas Tibbles was selected as his running mate.[18]

| Presidential ballot | 1st | 2nd | Vice-presidential ballot | 1st |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas E. Watson | 334 | 698 | Thomas H. Tibbles | 698 |

| William V. Allen | 319 | 0 | ||

| Samuel W. Williams | 45 | 0 |

Prohibition Party

The Prohibition Party met in Indianapolis from June 29 to July 1. The convention was attended by 758 delegates representing 39 states. Silas C. Swallow was selected as the party's presidential candidate and George W. Carrol was selected as the vice-presidential candidate.[18]

Socialist Labor Party

The Socialist Labor Party met at the Grand Central Palace in New York City from July 2 to July 8. Their convention was attended by 38 delegates representing 18 states. Those delegates nominated Charles H. Corregan and William W. Cox for president and vice-president respectively.[18]

National Liberty Party

The National Liberty Party met in St. Louis, Missouri from July 5 to 6 to nominate a presidential slate. While 28 delegates attended the convention and elected to nominate Stanley P. Mitchell and William C. Payne as their candidates, the party ultimately did not contest the election after Mitchell declined the nomination.[18]

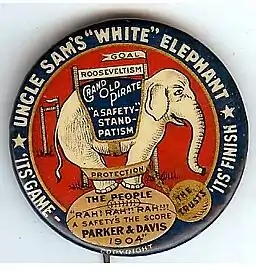

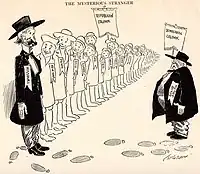

General election

Campaign

The campaigning done by both parties was much less vigorous than it had been in 1896 and 1900. The campaign season was pervaded by goodwill, and it went a long way toward mending the damage done by the previous class-war elections. This was due to the fact that Parker and Roosevelt, with the exception of charisma, were so similar in political outlook.

So close were the two candidates that few differences could be detected. Both men were for the gold standard; though the Democrats were more outspokenly against imperialism, both believed in fair treatment for the Filipinos and eventual liberation; and both believed that labor unions had the same rights as individuals before the courts. The radicals in the Democratic Party denounced Parker as a conservative; the conservatives in the Republican Party denounced Theodore Roosevelt as a radical.

During the campaign, there were a couple of instances in which Roosevelt was seen as vulnerable. In the first place, Joseph Pulitzer's New York World carried a full-page story about alleged corruption in the Bureau of Corporations. President Roosevelt admitted certain payments had been made, but denied any "blackmail." Secondly, in appointing George B. Cortelyou as his campaign manager, Roosevelt had purposely used his former Secretary of Commerce and Labor. This was of importance because Cortelyou, knowing the secrets of the corporations, could extract large contributions from them. The charge created quite a stir and in later years was proven to be sound. In 1907, it was disclosed that the insurance companies had contributed rather too heavily to the Roosevelt campaign. Only a week before the election, Roosevelt himself called E. H. Harriman, the railroad king, to Washington, D.C., for the purpose of raising funds to carry New York.[9]

Insider money, however, was spent on both candidates. Parker received financial support from the Morgan banking interests, just as Bourbon Democrat Cleveland had before him. Thomas W. Lawson, the Boston millionaire, charged that New York state Senator Patrick Henry McCarren, a prominent Parker backer, was on the payroll of Standard Oil at the rate of twenty thousand dollars a year. Lawson offered Senator McCarren $100,000 (equivalent to $3.3 million today) if he would disprove the charge.[7] According to one account, "No denial of the charge was ever made by the Senator." One paper even referred to McCarren as "the Standard Oil serpent of Brooklyn politics."[20]

Results

Theodore Roosevelt won a landslide victory, taking every Northern and Western state. He was the first Republican to carry the state of Missouri since Ulysses S. Grant in 1868. In voting Republican, Missouri repositioned itself from being associated with the Solid South to being seen as a bellwether swing state throughout the 20th century. The vote in Maryland was extremely close. For the first time in that state's history, secret paper ballots, supplied at public expense, and without political symbols of any kind, were issued to each voter. Candidates for Electors were listed under the presidential and vice presidential candidates for each party; there were four parties recognized in the election: Democratic, Republican, Prohibition, and Socialist. Voters were free to mark their ballots for up to eight candidates of any party. While Roosevelt's victory nationally was quickly determined, the election in Maryland remained in doubt for several weeks. On November 30, Roosevelt was declared the statewide victor by just 51 votes. However, as voters had voted for individual presidential electors, only one Republican elector, Charles Bonaparte, survived the tally. The other seven top vote recipients were Democrats.[21]

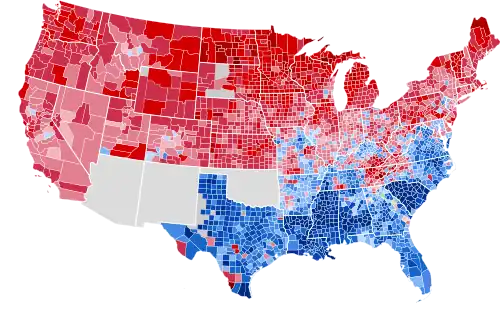

Roosevelt won the election by more than 2.5 million popular votes, making him the first president to win a primarily two-man race by more than a million votes. Roosevelt won 56.4% of the popular vote; that, along with his popular vote margin of 18.8%, was the largest recorded between James Monroe's uncontested re-election in 1820 and the election of Warren G. Harding in 1920. Of the 2,754 counties making returns, Roosevelt carried 1,611 (58.50%) and won a majority of votes in 1,538; he and Parker were tied in one county (0.04%).

Thomas Watson, the Populist candidate, received 117,183 votes and won nine counties (0.33%) in his home state of Georgia. He had a majority in five of the counties, and his vote total was double the Populist's showing in 1900 but less than one eighth of the party's total in 1892.

Parker carried 1,133 counties (41.14%) and won a majority in 1,057. The distribution of the vote by counties reveals him to have been a weaker candidate than William Jennings Bryan, the party's nominee four years earlier, in every section of the nation, except for the deep South, where Democratic dominance remained strong, due in large part to pervasive disfranchisement of blacks.[23] In 17 states, the Parker–Davis ticket failed to carry a single county, and outside the South carried only 84.[24]

This was the last election in which the Republicans won Colorado, Nebraska, and Nevada until 1920.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (Incumbent) | Republican | New York | 7,630,457 | 56.42% | 336 | Charles Warren Fairbanks | Indiana | 336 |

| Alton Brooks Parker | Democratic | New York | 5,083,880 | 37.59% | 140 | Henry Gassaway Davis | West Virginia | 140 |

| Eugene Victor Debs | Socialist | Indiana | 402,810 | 2.98% | 0 | Benjamin Hanford | New York | 0 |

| Silas Comfort Swallow | Prohibition | Pennsylvania | 259,102 | 1.92% | 0 | George Washington Carroll | Texas | 0 |

| Thomas Edward Watson | Populist | Georgia | 114,070 | 0.84% | 0 | Thomas Henry Tibbles | Nebraska | 0 |

| Charles Hunter Corregan | Socialist Labor | New York | 33,454 | 0.25% | 0 | William Wesley Cox | Illinois | 0 |

| Other | 1,229 | 0.01% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 13,525,002 | 100% | 476 | 476 | ||||

| Needed to win | 239 | 239 | ||||||

Source (popular vote): Leip, David. "1904 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 28, 2005.

Source (electoral vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

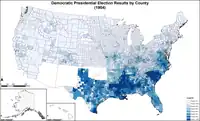

Geography of results

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Cartographic gallery

Map of presidential election results by county

Map of presidential election results by county Map of Republican presidential election results by county

Map of Republican presidential election results by county Map of Democratic presidential election results by county

Map of Democratic presidential election results by county Map of "other" presidential election results by county

Map of "other" presidential election results by county Cartogram of presidential election results by county

Cartogram of presidential election results by county Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county Cartogram of "other" presidential election results by county

Cartogram of "other" presidential election results by county

Results by state

| States/districts won by Parker/Davis |

| States/districts won by Roosevelt/Fairbanks |

| Theodore Roosevelt Republican |

Alton B. Parker Democratic |

Eugene V. Debs Socialist |

Silas Swallow Prohibition |

Thomas Watson Populist |

Charles Corregan Socialist Labor |

Margin | State total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | |

| Alabama | 11 | 22,472 | 20.66 | - | 79,797 | 73.35 | 11 | 853 | 0.78 | - | 612 | 0.56 | - | 5,051 | 4.64 | - | - | - | - | -57,325 | -52.70 | 108,785 | AL |

| Arkansas | 9 | 46,860 | 40.25 | - | 64,434 | 55.35 | 9 | 1,816 | 1.56 | - | 993 | 0.85 | - | 2,318 | 1.99 | - | - | - | - | -17,574 | -15.10 | 116,421 | AR |

| California | 10 | 205,226 | 61.84 | 10 | 89,404 | 26.94 | - | 29,535 | 8.90 | - | 7,380 | 2.22 | - | 2 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | 115,822 | 34.90 | 331,878 | CA |

| Colorado | 5 | 134,661 | 55.26 | 5 | 100,105 | 41.08 | - | 4,304 | 1.77 | - | 3,438 | 1.41 | - | 824 | 0.34 | - | 335 | 0.14 | - | 34,556 | 14.18 | 243,667 | CO |

| Connecticut | 7 | 111,089 | 58.12 | 7 | 72,909 | 38.15 | - | 4,543 | 2.38 | - | 1,506 | 0.79 | - | 495 | 0.26 | - | 575 | 0.30 | - | 38,180 | 19.98 | 191,128 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 23,705 | 54.05 | 3 | 19,347 | 44.11 | - | 146 | 0.33 | - | 607 | 1.38 | - | 51 | 0.12 | - | - | - | - | 4,358 | 9.94 | 43,856 | DE |

| Florida | 5 | 8,314 | 21.48 | - | 26,449 | 68.33 | 5 | 2,337 | 6.04 | - | - | - | - | 1,605 | 4.15 | - | - | - | - | -18,135 | -46.85 | 38,705 | FL |

| Georgia | 13 | 24,004 | 18.33 | - | 83,466 | 63.72 | 13 | 196 | 0.15 | - | 685 | 0.52 | - | 22,635 | 17.28 | - | - | - | - | -59,462 | -45.40 | 130,986 | GA |

| Idaho | 3 | 47,783 | 65.84 | 3 | 18,480 | 25.46 | - | 4,949 | 6.82 | - | 1,013 | 1.40 | - | 353 | 0.49 | - | - | - | - | 29,303 | 40.37 | 72,578 | ID |

| Illinois | 27 | 632,645 | 58.77 | 27 | 327,606 | 30.43 | - | 69,225 | 6.43 | - | 34,770 | 3.23 | - | 6,725 | 0.62 | - | 4,698 | 0.44 | - | 305,039 | 28.34 | 1,076,499 | IL |

| Indiana | 15 | 368,289 | 53.99 | 15 | 274,345 | 40.22 | - | 12,013 | 1.76 | - | 23,496 | 3.44 | - | 2,444 | 0.36 | - | 1,598 | 0.23 | - | 93,944 | 13.77 | 682,185 | IN |

| Iowa | 13 | 308,158 | 63.39 | 13 | 149,276 | 30.71 | - | 14,849 | 3.05 | - | 11,603 | 2.39 | - | 2,207 | 0.45 | - | - | - | - | 158,882 | 32.69 | 486,093 | IA |

| Kansas | 10 | 212,955 | 64.81 | 10 | 86,174 | 26.23 | - | 15,869 | 4.83 | - | 7,306 | 2.22 | - | 6,257 | 1.90 | - | - | - | - | 126,781 | 38.59 | 328,561 | KS |

| Kentucky | 13 | 205,457 | 47.13 | - | 217,170 | 49.82 | 13 | 3,599 | 0.83 | - | 6,603 | 1.51 | - | 2,521 | 0.58 | - | 596 | 0.14 | - | -11,713 | -2.69 | 435,946 | KY |

| Louisiana | 9 | 5,205 | 9.66 | - | 47,708 | 88.50 | 9 | 995 | 1.85 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -42,503 | -78.84 | 53,908 | LA |

| Maine | 6 | 65,432 | 67.44 | 6 | 27,642 | 28.49 | - | 2,102 | 2.17 | - | 1,510 | 1.56 | - | 337 | 0.35 | - | - | - | - | 37,790 | 38.95 | 97,023 | ME |

| Maryland | 8 | 109,497 | 48.83 | 1 | 109,446 | 48.81 | 7 | 2,247 | 1.00 | - | 3,034 | 1.35 | - | 1 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | 51 | 0.02 | 224,229 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 16 | 257,822 | 57.92 | 16 | 165,746 | 37.24 | - | 13,604 | 3.06 | - | 4,279 | 0.96 | - | 1,294 | 0.29 | - | 2,359 | 0.53 | - | 92,076 | 20.69 | 445,109 | MA |

| Michigan | 14 | 364,957 | 69.51 | 14 | 135,392 | 25.79 | - | 9,042 | 1.72 | - | 13,441 | 2.56 | - | 1,159 | 0.22 | - | 1,036 | 0.20 | - | 229,565 | 43.72 | 525,027 | MI |

| Minnesota | 11 | 216,651 | 73.98 | 11 | 55,187 | 18.84 | - | 11,692 | 3.99 | - | 6,253 | 2.14 | - | 2,103 | 0.72 | - | 974 | 0.33 | - | 161,464 | 55.13 | 292,860 | MN |

| Mississippi | 10 | 3,280 | 5.59 | - | 53,480 | 91.07 | 10 | 462 | 0.79 | - | - | - | - | 1,499 | 2.55 | - | - | - | - | -50,200 | -85.49 | 58,721 | MS |

| Missouri | 18 | 321,449 | 49.93 | 18 | 296,312 | 46.02 | - | 13,009 | 2.02 | - | 7,191 | 1.12 | - | 4,226 | 0.66 | - | 1,674 | 0.26 | - | 25,137 | 3.90 | 643,861 | MO |

| Montana | 3 | 34,932 | 54.21 | 3 | 21,773 | 33.79 | - | 5,676 | 8.81 | - | 335 | 0.52 | - | 1,520 | 2.36 | - | 208 | 0.32 | - | 13,159 | 20.42 | 64,444 | MT |

| Nebraska | 8 | 138,558 | 61.38 | 8 | 52,921 | 23.44 | - | 7,412 | 3.28 | - | 6,323 | 2.80 | - | 20,518 | 9.09 | - | - | - | - | 85,637 | 37.94 | 225,732 | NE |

| Nevada | 3 | 6,864 | 56.66 | 3 | 3,982 | 32.87 | - | 925 | 7.64 | - | - | - | - | 344 | 2.84 | - | - | - | - | 2,882 | 23.79 | 12,115 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 54,163 | 60.07 | 4 | 34,074 | 37.79 | - | 1,090 | 1.21 | - | 750 | 0.83 | - | 83 | 0.09 | - | - | - | - | 20,089 | 22.28 | 90,161 | NH |

| New Jersey | 12 | 245,164 | 56.68 | 12 | 164,566 | 38.05 | - | 9,587 | 2.22 | - | 6,845 | 1.58 | - | 3,705 | 0.86 | - | 2,680 | 0.62 | - | 80,598 | 18.63 | 432,547 | NJ |

| New York | 39 | 859,533 | 53.13 | 39 | 683,981 | 42.28 | - | 36,883 | 2.28 | - | 20,787 | 1.28 | - | 7,459 | 0.46 | - | 9,127 | 0.56 | - | 175,552 | 10.85 | 1,617,770 | NY |

| North Carolina | 12 | 82,442 | 39.67 | - | 124,091 | 59.71 | 12 | 124 | 0.06 | - | 342 | 0.16 | - | 819 | 0.39 | - | - | - | - | -41,649 | -20.04 | 207,818 | NC |

| North Dakota | 4 | 52,595 | 75.12 | 4 | 14,273 | 20.39 | - | 2,009 | 2.87 | - | 1,137 | 1.62 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 38,322 | 54.73 | 70,014 | ND |

| Ohio | 23 | 600,095 | 59.75 | 23 | 344,674 | 34.32 | - | 36,260 | 3.61 | - | 19,339 | 1.93 | - | 1,392 | 0.14 | - | 2,633 | 0.26 | - | 255,421 | 25.43 | 1,004,393 | OH |

| Oregon | 4 | 60,455 | 67.06 | 4 | 17,521 | 19.43 | - | 7,619 | 8.45 | - | 3,806 | 4.22 | - | 753 | 0.84 | - | - | - | - | 42,934 | 47.62 | 90,154 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 34 | 840,949 | 68.00 | 34 | 337,998 | 27.33 | - | 21,863 | 1.77 | - | 33,717 | 2.73 | - | - | - | - | 2,211 | 0.18 | - | 502,951 | 40.67 | 1,236,738 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 41,605 | 60.60 | 4 | 24,839 | 36.18 | - | 956 | 1.39 | - | 768 | 1.12 | - | - | - | - | 488 | 0.71 | - | 16,766 | 24.42 | 68,656 | RI |

| South Carolina | 9 | 2,554 | 4.63 | - | 52,563 | 95.36 | 9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.00 | - | - | - | - | -50,009 | -90.73 | 55,118 | SC |

| South Dakota | 4 | 72,083 | 71.09 | 4 | 21,969 | 21.67 | - | 3,138 | 3.09 | - | 2,965 | 2.92 | - | 1,240 | 1.22 | - | - | - | - | 50,114 | 49.42 | 101,395 | SD |

| Tennessee | 12 | 105,363 | 43.40 | - | 131,653 | 54.23 | 12 | 1,354 | 0.56 | - | 1,889 | 0.78 | - | 2,491 | 1.03 | - | - | - | - | -26,290 | -10.83 | 242,750 | TN |

| Texas | 18 | 51,242 | 21.90 | - | 167,200 | 71.45 | 18 | 2,791 | 1.19 | - | 4,292 | 1.83 | - | 8,062 | 3.45 | - | 421 | 0.18 | - | -115,958 | -49.55 | 234,008 | TX |

| Utah | 3 | 62,446 | 61.42 | 3 | 33,413 | 32.86 | - | 5,767 | 5.67 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 29,033 | 28.56 | 101,672 | UT |

| Vermont | 4 | 40,459 | 77.97 | 4 | 9,777 | 18.84 | - | 859 | 1.66 | - | 792 | 1.53 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 30,682 | 59.13 | 51,888 | VT |

| Virginia | 12 | 48,180 | 36.95 | - | 80,649 | 61.84 | 12 | 202 | 0.15 | - | 1,379 | 1.06 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -32,469 | -24.90 | 130,410 | VA |

| Washington | 5 | 101,540 | 69.95 | 5 | 28,098 | 19.36 | - | 10,023 | 6.91 | - | 3,229 | 2.22 | - | 669 | 0.46 | - | 1,592 | 1.10 | - | 73,442 | 50.60 | 145,151 | WA |

| West Virginia | 7 | 132,620 | 55.26 | 7 | 100,855 | 42.03 | - | 1,573 | 0.66 | - | 4,599 | 1.92 | - | 339 | 0.14 | - | - | - | - | 31,765 | 13.24 | 239,986 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 13 | 280,315 | 63.21 | 13 | 124,205 | 28.01 | - | 28,240 | 6.37 | - | 9,872 | 2.23 | - | 560 | 0.13 | - | 249 | 0.06 | - | 156,110 | 35.20 | 443,441 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | 20,489 | 66.72 | 3 | 8,930 | 29.08 | - | 1,072 | 3.49 | - | 217 | 0.71 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11,559 | 37.64 | 30,708 | WY |

| TOTALS: | 476 | 7,630,557 | 56.42 | 336 | 5,083,880 | 37.59 | 140 | 402,810 | 2.98 | - | 259,103 | 1.92 | - | 114,062 | 0.84 | - | 33,454 | 0.25 | - | 2,546,677 | 18.83 | 13,525,095 | US |

Close states

.jpg.webp)

Margin of victory less than 1% (8 electoral votes):

- Maryland, 0.02% (51 votes)

Margin of victory less than 5% (31 electoral votes):

- Kentucky, 2.69% (11,713 votes)

- Missouri, 3.90% (25,137 votes)

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (3 electoral votes):

- Delaware, 9.94% (4,358 votes)

Tipping point state:

- New Jersey, 18.63% (80,598 votes)

Statistics

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

- Keweenaw County, Michigan 94.55%

- Mercer County, North Dakota 93.68%

- Logan County, North Dakota 93.61%

- McIntosh County, North Dakota 92.70%

- Zapata County, Texas 92.48%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

- Horry County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Georgetown County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Fairfield County, South Carolina 100.00%

- Madison Parish, Louisiana 100.00%

- Potter County, Texas 100.00%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Populist)

- Glascock County, Georgia 69.38%

- McDuffie County, Georgia 58.59%

- McIntosh County, Georgia 56.55%

- Jackson County, Georgia 55.29%

- Johnson County, Georgia 53.05%

See also

References

- "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press.

- "Theodore Roosevelt: Campaigns and Elections—Miller Center". Millercenter.org. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- Bain, Richard C.; Parris, Judith H. (1973). Convention Decisions and Voting Records. Studies in Presidential Selection (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution. ISBN 0-8157-0768-1.

- Havel, James T. (1996). U.S. Presidential Elections and the Candidates: A Biographical and Historical Guide. Vol. 2: The Elections, 1789–1992. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-02-864623-1.

- "Bryan Back, is Not a Candidate" (PDF). The New York Times. January 10, 1904. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- National Party Conventions, 1831-1976. Congressional Quarterly. 1979.

- "E. V. Debs: The Socialist Party and the Working Class". Archived from the original on September 22, 2002. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- "Official report of the proceedings of the Democratic national convention". Kdl.kyvl.org. p. 277. Archived from the original on January 13, 2013. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- Stone, Irving (1943). They Also Ran. New York: Doubleday.

- "Official report of the proceedings of the Democratic national convention". Kdl.kyvl.org. p. 278. Archived from the original on January 13, 2013. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- Richardson, Darcy (April 2007). Others: Third Parties During the Populist Period. Vol. II. New York, NY: iUniverse. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-5954-4304-8 – via Google Books.

- Mowry, George (1958). The Era of Theodore Roosevelt, 1900–1912. New York: Harper. p. 178.

- DeGregorio, William (1997). The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents. Gramercy.

- Currie, Harold W. (1976). Eugene V. Debs. Twayne Publishers.

- Mailly, William (1904). Proceedings of the National Convention of the Socialist Party. Socialist Party of America.

- Karsner, David (1919). Debs - Authorized Life and Letters.

- Hinshaw, Seth (2000). Ohio Elects the President: Our State's Role in Presidential Elections 1804-1996. Mansfield: Book Masters, Inc. p. 74.

- "Won't Be Continental Party Nominee". The New York Times. September 8, 1904. p. 5. ProQuest 96402797. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- "The Bowery Boys: New York City History". Theboweryboys.blogspot.com. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- "Too Close to Call: Presidential Electors and Elections in Maryland featuring the Presidential Election of 1904". Msa.maryland.gov. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- The Presidential Vote, 1896-1932 – Google Books. Stanford University Press. 1934. ISBN 9780804716963. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- Presidential Elections, 1789–2008: County, State, and National Mapping of Election Data, Donald R. Deskins Jr., Hanes Walton Jr., and Sherman C. Puckett, p. 281.

- The Presidential Vote, 1896-1932, Edgar E. Robinson, pp. 11–12.

- "1904 Presidential General Election Data - National". Uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

Further reading

- Doss, Richard B. (1954). "Democrats in the Doldrums: Virginia and the Democratic National Convention of 1904". Journal of Southern History. 20 (4): 511–529. doi:10.2307/2954738. JSTOR 2954738.

- Gould, Lewis L. (1991). The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0435-9.

- Harbaugh, William Henry (1961). Power and Responsibility: The Life and Times of Theodore Roosevelt. New York: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy.

- Morris, Edmund (2001). Theodore Rex. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-55509-0. Biography of Roosevelt during the years 1901–1909.

- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier, and Fred L. Israel, eds. History of American presidential elections, 1789-1968. Vol. 3. (1971), history of the campaign by William Harbaugh, with primary documents.

- Shoemaker, Fred C. "Alton B. Parker: the images of a gilded age statesman in an era of progressive politics" (MA thesis, The Ohio State University, 1983) online.

Primary sources

- Republican Campaign Text-book, 1904 (1904), handbook for Republican speakers and editorialists; full of arguments, speeches and statistics online free

- Chester, Edward W A guide to political platforms (1977) online

- Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. National party platforms, 1840-1964 (1965) online 1840-1956

External links

- Presidential Election of 1904: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- 1904 popular vote by counties

- TheodoreRoosevelt.com

- Newspaper Article about Judge Parker Nomination For President

- Newspaper Article about President Roosevelt Nomination For President

- Election of 1904 in Counting the Votes Archived October 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

.jpg.webp)