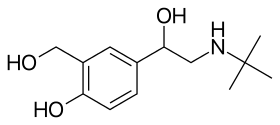

Beta2-adrenergic agonist

Beta2-adrenergic agonists, also known as adrenergic β2 receptor agonists, are a class of drugs that act on the β2 adrenergic receptor. Like other β adrenergic agonists, they cause smooth muscle relaxation. β2 adrenergic agonists' effects on smooth muscle cause dilation of bronchial passages, vasodilation in muscle and liver, relaxation of uterine muscle, and release of insulin. They are primarily used to treat asthma and other pulmonary disorders, such as Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[1]

Mechanism of action

Activation of β adrenergic receptors leads to relaxation of smooth muscle in the lung, and dilation and opening of the airways.[2]

β adrenergic receptors are coupled to a stimulatory G protein of adenylyl cyclase. This enzyme produces the second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). In the lung, cAMP decreases calcium concentrations within cells and activates protein kinase A. Both of these changes inactivate myosin light-chain kinase and activate myosin light-chain phosphatase. In addition, β2 agonists open large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels and thereby tend to hyperpolarize airway smooth muscle cells. The combination of decreased intracellular calcium, increased membrane potassium conductance, and decreased myosin light chain kinase activity leads to smooth muscle relaxation and bronchodilation.[2]

Adverse effects

Findings indicate that β2 stimulants, especially in parenteral administration such as inhalation or injection, can induce adverse effects:

- Tachycardia secondary to peripheral vasodilation and cardiac stimulation (Such tachycardia may be accompanied by palpitations.)[3]

- Tremor, excessive sweating, anxiety, insomnia, and agitation[4]

- More severe effects include paradoxical bronchospasm, hypokalemia, and in rare cases a myocardial infarction.[3] (More severe effects, such as pulmonary edema, myocardial ischemia, and cardiac arrhythmia, are exceptional.)[5][6][7]

Overuse of β2 agonists and asthma treatment without proper inhaled corticosteroid use has been associated with an increased risk of asthma exacerbations and asthma-related hospitalizations.[8] The excipients, in particular sulfite, could contribute to the adverse effects.

Delivery

All β2 agonists are available in inhaler form, as either metered-dose inhalers which dispense an aerosolized drug and contains propellants, dry powder inhalers which dispense a powder to be inhaled, or soft mist inhalers which dispense a mist without use of propellants.[9]

Salbutamol (INN) or albuterol (USAN) and some other β2 agonists, such as formoterol, also are sold in a solution form for nebulization, which is more commonly used than inhalers in emergency rooms.[9] Nebulizers continuously deliver aerosolized drug and salbutamol delivered through nebulizer was found to be more effective than IV administration.[10]

Salbutamol and terbutaline are also both available in oral forms.[11] In addition, several of these medications are available in intravenous forms, including both salbutamol and terbutaline. It can be used in this form in severe cases of asthma, but it is more commonly used to suppress premature labor because it also relaxes uterine muscle, thereby inhibiting contractions.[12]

Risks

On 18 November 2005, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) alerted healthcare professionals and patients that several long-acting bronchodilator medicines have been associated with possible increased risk of worsening wheezing in some people, and requested that manufacturers update warnings in their existing product labeling.

A 2006 meta-analysis found that "regularly inhaled β agonists (orciprenaline/metaproterenol [Alupent], formoterol [Foradil], fluticasone+salmeterol [Serevent, Advair], and salbutamol/albuterol [Proventil, Ventolin, Volmax, and others]) increased the risk of respiratory death more than two-fold, compared with a placebo," while used to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[13] On 11 December 2008, a panel of experts convened by the FDA voted to ban drugs Serevent and Foradil from use in the treatment of asthma. When these two drugs are used without steroids, they increase the risks of more severe attacks. They said that two other, much more popular, asthma drugs containing long-acting β agonists—Advair and Symbicort—should continue to be used.[14]

Types

They can be divided into short-acting, long-acting, and ultra-long-acting beta adrenoreceptor agonists:

Generic name—Trade name

Short-acting β2 agonists (SABAs)

- bitolterol—Tornalate

- fenoterol—Berotec

- isoprenaline (INN) or isoproterenol (USAN)—Isuprel

- levosalbutamol (INN) or levalbuterol (USAN)—Xopenex

- orciprenaline (INN) or metaproterenol (USAN)—Alupent

- pirbuterol—Maxair

- procaterol

- ritodrine—Yutopar

- salbutamol (INN) or albuterol (USAN)—Ventolin

- terbutaline—Bricanyl

Long-acting β2 agonists (LABAs)

- arformoterol—Brovana (some consider it to be an ultra-LABA)[15]

- bambuterol—Bambec, Oxeol

- clenbuterol—Dilaterol, Spiropent

- formoterol—Foradil, Oxis, Perforomist

- salmeterol—Serevent

Ultra-long-acting β2 agonists

- abediterol[16]

- carmoterol

- indacaterol—Arcapta Neohaler (U.S.), Onbrez Breezhaler (EU, RU)

- olodaterol—Striverdi Respimat

- vilanterol

- with umeclidinium bromide—Anoro Ellipta

- with fluticasone furoate—Breo Ellipta (U.S.), Relvar Ellipta (EU, RU)

- with fluticasone furoate and umeclidinium bromide—Trelegy Ellipta

Unknown duration of action

- isoxsuprine

- mabuterol

- zilpaterol—Zilmax

Society and culture

β2 agonists are used by athletes and bodybuilders as anabolic performance-enhancing drugs and their use has been banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency except for certain drugs that people with asthma may use; they are also used illegally to try to promote the growth of livestock.[19] A 2011 meta-analysis found no evidence that inhaled β₂-agonists improve performance in healthy athletes and found that the evidence was too weak to assess whether systemic administration of β₂-agonists improved performance in healthy people.[20]

References

- Eric, Hsu; Tushar, Bajaj (2022). "Beta 2 Agonists". NCBI. PMID 31194406. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- Proskocil, Becky J.; Fryer, Allison D. (1 November 2005). "β2-Agonist and Anticholinergic Drugs in the Treatment of Lung Disease". Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2 (4): 305–310. doi:10.1513/pats.200504-038SR. ISSN 1546-3222. PMID 16267353. S2CID 22198277.

- Almadhoun, Khaled; Sharma, Sandeep (2020), "Bronchodilators", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30085570, retrieved 16 March 2020

- Billington, Charlotte K.; Penn, Raymond B.; Hall, Ian P. (2016). "β2 Agonists". Pharmacology and Therapeutics of Asthma and COPD. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 237. pp. 23–40. doi:10.1007/164_2016_64. ISBN 978-3-319-52173-2. PMC 5480238. PMID 27878470.

- Lulich, K. M.; Goldie, R. G.; Ryan, G.; Paterson, J. W. (July 1986). "Adverse reactions to beta 2-agonist bronchodilators". Medical Toxicology. 1 (4): 286–299. doi:10.1007/bf03259844. ISSN 0112-5966. PMID 2878344. S2CID 58394547.

- McCoshen, John A.; Fernandes, P. Audrey; Boroditsky, Michael L.; Allardice, James G. (1 January 1996). "Determinants of Reproductive Mortality and Preterm Childbirth". In Bittar, E. Edward; Zakar, Tamas (eds.). Pregnancy and Parturition. pp. 195–223. doi:10.1016/S1569-2590(08)60073-7. ISBN 9781559386395.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Hsu, Eric; Bajaj, Tushar (2020), "Beta 2 Agonists", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31194406, retrieved 18 March 2020

- Reddel, Helen K.; Bacharier, Leonard B.; Bateman, Eric D.; Brightling, Christopher E.; Brusselle, Guy G.; Buhl, Roland; Cruz, Alvaro A.; Duijts, Liesbeth; Drazen, Jeffrey M.; FitzGerald, J. Mark; Fleming, Louise J.; Inoue, Hiromasa; Ko, Fanny W.; Krishnan, Jerry A.; Levy, Mark L. (1 January 2022). "Global Initiative for Asthma Strategy 2021: executive summary and rationale for key changes". The European Respiratory Journal. 59 (1): 2102730. doi:10.1183/13993003.02730-2021. ISSN 0903-1936. PMC 8719459. PMID 34667060.

- Sorino, Claudio; Negri, Stefano; Spanevello, Antonio; Visca, Dina; Scichilone, Nicola (1 May 2020). "Inhalation therapy devices for the treatment of obstructive lung diseases: the history of inhalers towards the ideal inhaler". European Journal of Internal Medicine. 75: 15–18. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2020.02.023. ISSN 0953-6205. PMID 32113944. S2CID 211727980.

- Gad, S.E. (2014), "Albuterol", Encyclopedia of Toxicology, Elsevier, pp. 112–115, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-386454-3.00809-5, ISBN 978-0-12-386455-0, retrieved 24 April 2023

- Jaeggi, Edgar T.; Tulzer, Gerald (2010). "CHAPTER 12 - Pharmacological and Interventional Fetal Cardiovascular Treatment". Paediatric Cardiology (Third ed.). pp. 199–218. doi:10.1016/B978-0-7020-3064-2.00012-6. ISBN 9780702030642.

- Motazedian, Shahdokht; Ghaffarpasand, Fariborz; Mojtahedi, Khatereh; Asadi, Nasrin (2010). "Terbutaline versus salbutamol for suppression of preterm labor: a randomized clinical trial". Annals of Saudi Medicine. 30 (5): 370–375. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.67079. ISSN 0256-4947. PMC 2941249. PMID 20697169.

- Salpeter SR, Buckley NS, Salpeter EE (October 2006). "Meta-analysis: anticholinergics, but not beta-agonists, reduce severe exacerbations and respiratory mortality in COPD". J Gen Intern Med. 21 (10): 1011–9. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00507.x. PMC 1831628. PMID 16970553.

- Lay summary in: Ramanujan K (29 June 2006). "Common beta-agonist inhalers more than double death rate in COPD patients, Cornell and Stanford scientists assert". Cornell Chronicle.

- Harris, Gardiner (11 December 2008). "F.D.A. Panel Votes to Ban Asthma Drugs". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- Matera, MG; Cazzola, M (2007). "Ultra-Long-Acting β2-Adrenoceptor Agonists: An Emerging Therapeutic Option for Asthma and COPD?". Drugs. 67 (4): 503–15. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767040-00002. PMID 17352511. S2CID 46976912. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Beier, J; Fuhr, R; Massana, E; Jiménez, E; Seoane, B; de Miquel, G; Ruiz, S (October 2014). "Abediterol (LAS100977), a novel long-acting β2-agonist: Efficacy, safety and tolerability in persistent asthma". Respiratory Medicine. 108 (10): 1424–1429. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2014.08.005. PMID 25256258. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Cazzola, Mario; Matera, Maria Gabriella; Lötvall, Jan (15 July 2005). "Ultra long-acting β2-agonists in development for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 14 (7): 775–83. doi:10.1517/13543784.14.7.775. PMID 16022567. S2CID 11930383.

- Cazzola, Mario; Calzetta, Luigino; Matera, Maria Gabriella (May 2011). "β2-adrenoceptor agonists: current and future direction". British Journal of Pharmacology. 163 (1): 4–17. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01216.x. PMC 3085864. PMID 21232045.

- Drug Enforcement Administration. November 2013 Clenbuterol Archived 17 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Pluim BM, de Hon O, Staal JB, Limpens J, Kuipers H, Overbeek SE, Zwinderman AH, Scholten RJ (January 2011). "β₂-Agonists and physical performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Sports Med. 41 (1): 39–57. doi:10.2165/11537540-000000000-00000. PMID 21142283. S2CID 189906919.

External links

- Adrenergic beta-Agonists at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)