The Waste Land

The Waste Land is a poem by T. S. Eliot, widely regarded as one of the most important English language poems of the 20th century and a central work of modernist poetry.[2][3] Published in 1922, the 434-line[upper-alpha 1] poem first appeared in the United Kingdom in the October issue of Eliot's The Criterion and in the United States in the November issue of The Dial. It was published in book form in December 1922. Among its famous phrases are "April is the cruelest month", "I will show you fear in a handful of dust", "These fragments I have shored against my ruins" and the Sanskrit mantra "Datta, Dayadhvam, Damyata" and "Shantih shantih shantih".[upper-alpha 2]

Eliot_Boni.djvu.jpg.webp) Title page | |

| Author | T. S. Eliot |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Boni & Liveright |

Publication date | 1922 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 64 pp[1] |

| Text | The Waste Land at Wikisource |

Eliot's poem combines the legend of the Holy Grail and the Fisher King with vignettes of contemporary British society. Eliot employs many allusions to the Western canon: Ovid's Metamorphoses, Dante's Divine Comedy, Shakespeare, Milton, Buddhist scriptures, the Hindu Upanishads and even a contemporary popular song, "The Shakespearean Rag." The poem shifts between voices of satire and prophecy featuring abrupt and unannounced changes of speaker, location, and time and conjuring a vast and dissonant range of cultures and literatures.

The poem is divided into five sections. The first, "The Burial of the Dead", introduces the diverse themes of disillusionment and despair. The second, "A Game of Chess", employs alternating narrations, in which vignettes of several characters address those themes experientially. "The Fire Sermon", the third section, offers a philosophical meditation in relation to the imagery of death and views of self-denial in juxtaposition, influenced by Augustine of Hippo and Eastern religions. After a fourth section, "Death by Water", which includes a brief lyrical petition, the culminating fifth section, "What the Thunder Said", concludes with an image of judgment.

Composition history

Writing

Eliot probably worked on the text that became The Waste Land for several years preceding its first publication in 1922. In a May 1921 letter to New York lawyer and patron of modernism John Quinn, Eliot wrote that he had "a long poem in mind and partly on paper which I am wishful to finish".[4]

Richard Aldington, in his memoirs, relates that "a year or so" before Eliot read him the manuscript draft of The Waste Land in London, Eliot visited him in the country.[5] While walking through a graveyard, they discussed Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard. Aldington writes: "I was surprised to find that Eliot admired something so popular, and then went on to say that if a contemporary poet, conscious of his limitations as Gray evidently was, would concentrate all his gifts on one such poem he might achieve a similar success."[5]

Eliot, having been diagnosed with some form of nervous disorder, had been recommended rest, and applied for three months' leave from the bank where he was employed; the reason stated on his staff card was "nervous breakdown". He and his first wife, Vivienne Haigh-Wood Eliot, travelled to the coastal resort of Margate, Kent, for a period of convalescence.[6] While there, Eliot worked on the poem, and possibly showed an early version to Ezra Pound when the Eliots travelled to Paris in November 1921 and stayed with him. Eliot was en route to Lausanne, Switzerland, for treatment by Doctor Roger Vittoz, who had been recommended to him by Ottoline Morrell; Vivienne was to stay at a sanatorium just outside Paris. In Hotel Ste. Luce (where Hotel Elite has stood since 1938) in Lausanne, Eliot produced a 19-page version of the poem.[7] He returned from Lausanne in early January 1922. Pound then made detailed editorial comments and significant cuts to the manuscript. Eliot later dedicated the poem to Pound. Letters written by both Vivienne and Eliot give some insight into the creation of the poem.[8]

Manuscript drafts

Eliot sent the manuscript drafts of the poem to John Quinn in October 1922; they reached Quinn in New York in January 1923.[upper-alpha 3] Upon Quinn's death in 1924 they were inherited by his sister Julia Anderson. Years later, in the early 1950s, Mrs Anderson's daughter Mary Conroy found the documents in storage. In 1958 she sold them privately to the New York Public Library.

It was not until April 1968, three years after Eliot's death, that the existence and whereabouts of the manuscript drafts were made known to Valerie Eliot, the poet's second wife and widow.[9] In 1971, Faber and Faber published a "facsimile and transcript" of the original drafts, edited and annotated by Valerie Eliot. The full poem prior to the Pound editorial changes is contained in the facsimile.

Editing

The drafts of the poem reveal that it originally contained almost twice as much material as the final published version. The significant cuts are in part due to Ezra Pound's suggested changes, although Eliot himself also removed large sections.

The opening lines of the poem—"April is the cruellest month, breeding / Lilacs out of the dead land"—did not originally appear until the top of the second page of the typescript. The first page of the typescript contained 54 lines in the sort of street voice that we hear again at the end of the second section, A Game of Chess. This page appears to have been lightly crossed out in pencil by Eliot himself.

Although there are several signs of similar adjustments made by Eliot, and a number of significant comments by Vivienne, the most significant editorial input is clearly that of Pound, who recommended many cuts to the poem.

'The typist home at teatime' section was originally in entirely regular stanzas of iambic pentameter, with a rhyme scheme of abab—the same form as Gray's Elegy, which was in Eliot's thoughts around this time. Pound's note against this section of the draft is "verse not interesting enough as verse to warrant so much of it". In the end, the regularity of the four-line stanzas was abandoned.

At the beginning of 'The Fire Sermon' in one version, there was a lengthy section in heroic couplets, in imitation of Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock. It described one lady Fresca (who appeared in the earlier poem "Gerontion"). Richard Ellmann said "Instead of making her toilet like Pope's Belinda, Fresca is going to it, like Joyce's Bloom."[10] The lines read:

Leaving the bubbling beverage to cool,

Fresca slips softly to the needful stool,

Where the pathetic tale of Richardson

Eases her labour till the deed is done ...

Ellmann notes: "Pound warned Eliot that since Pope had done the couplets better, and Joyce the defecation, there was no point in another round."

Pound also excised some shorter poems that Eliot wanted to insert between the five sections. One of these, that Eliot had entitled 'Dirge', begins

Full fathom five your Bleistein lies[upper-alpha 4]

Under the flatfish and the squids.

Graves' disease in a dead Jew's eyes!

Where the crabs have eat the lids

...

At the request of Eliot's wife Vivienne, three lines in the A Game of Chess section were removed from the poem: "And we shall play a game of chess / The ivory men make company between us / Pressing lidless eyes and waiting for a knock upon the door". This section is apparently based on their marital life, and she may have felt these lines too revealing. However, the "ivory men" line may have meant something to Eliot: in 1960, thirteen years after Vivienne's death, he inserted the line in a copy made for sale to aid the London Library, of which he was president at the time; it fetched £2,800.[11] Rupert Hart-Davis had requested the original manuscript for the auction, but Eliot had lost it long ago (though it was found in America years later).[12]

In a late December 1921 letter to Eliot to celebrate the "birth" of the poem, Pound wrote a bawdy poem of 48 lines entitled "Sage Homme" in which he identified Eliot as the mother of the poem but compared himself to the midwife.[13] The first lines are:

These are the poems of Eliot

By the Uranian Muse begot;

A Man their Mother was,

A Muse their Sire.

How did the printed Infancies result

From Nuptials thus doubly difficult?

If you must needs enquire

Know diligent Reader

That on each Occasion

Ezra performed the Caesarean Operation.

Publishing history

Before the editing had even begun, Eliot found a publisher.[upper-alpha 5] Horace Liveright of the New York publishing firm of Boni & Liveright was in Paris for a number of meetings with Ezra Pound. At a dinner on 3 January 1922 (see 1922 in poetry), he made offers for works by Pound, James Joyce (Ulysses) and Eliot. Eliot was to get a royalty of 15% for a book version of the poem planned for autumn publication.[14]

To maximise his income and reach a broader audience, Eliot also sought a deal with magazines. Being the London correspondent for The Dial magazine[15] and a college friend of its co-owner and co-editor, Scofield Thayer, The Dial was an ideal choice. Even though The Dial offered $150 (£34)[16] for the poem (25% more than its standard rate) Eliot was offended that a year's work would be valued so low, especially since another contributor was found to have been given exceptional compensation for a short story.[17] The deal with The Dial almost fell through (other magazines considered were the Little Review and Vanity Fair), but with Pound's efforts eventually a deal was worked out where, in addition to the $150, Eliot would be awarded The Dial's second annual prize for outstanding service to letters. The prize carried an award of $2,000 (£450).[18]

In New York in the late summer (with John Quinn, a lawyer and literary patron, representing Eliot's interests) Boni & Liveright made an agreement with The Dial allowing the magazine to be the first to publish the poem in the US if they agreed to purchase 350 copies of the book at discount from Boni & Liveright.[19] Boni & Liveright would use the publicity of the award of The Dial's prize to Eliot to increase their initial sales.

The poem was first published in the UK, without the author's notes, in the first issue (October 1922) of The Criterion, a literary magazine started and edited by Eliot. The first appearance of the poem in the US was in the November 1922 issue of The Dial magazine (actually published in late October). In December 1922, the poem was published in the US in book form by Boni & Liveright, the first publication to print the notes. In September 1923, the Hogarth Press, a private press run by Eliot's friends Leonard and Virginia Woolf, published the first UK book edition of The Waste Land in an edition of about 450 copies, the type handset by Virginia Woolf.

The publication history of The Waste Land (as well as other pieces of Eliot's poetry and prose) has been documented by Donald Gallup.[1]

Eliot, whose 1922 annual salary at Lloyds Bank was £500 ($2,215),[20] made approximately £630 ($2,800) with The Dial, Boni & Liveright, and Hogarth Press publications.[21][upper-alpha 6]

Title

Eliot originally considered entitling the poem He do the Police in Different Voices.[23] In the version of the poem Eliot brought back from Switzerland, the first two sections of the poem—'The Burial of the Dead' and 'A Game of Chess'—appeared under this title. This strange phrase is taken from Charles Dickens' novel Our Mutual Friend, in which the widow Betty Higden says of her adopted foundling son Sloppy, "You mightn't think it, but Sloppy is a beautiful reader of a newspaper. He do the Police in different voices." Some critics use this working title to support the theory that, while there are many different voices (speakers) in the poem, there is only one central consciousness. What was lost by the rejection of this title Eliot might have felt compelled to restore by commenting on the commonalities of his characters in his note about Tiresias, stating that 'What Tiresias sees, in fact, is the substance of the poem.'

In the end, the title Eliot chose was The Waste Land. In his first note to the poem he attributes the title to Jessie Weston's book on the Grail legend, From Ritual to Romance. The allusion is to the wounding of the Fisher King and the subsequent sterility of his lands; to restore the King and make his lands fertile again, the Grail questor must ask, "What ails you?" In 1913, Madison Cawein published a poem called "Waste Land"; scholars have identified the poem as an inspiration to Eliot.[24]

The poem's title is often mistakenly given as "Waste Land" (as used by Weston) or "Wasteland", omitting the definite article. However, in a letter to Ezra Pound, Eliot politely insisted that the title was three words beginning with "The".[25]

Structure

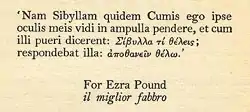

The poem is preceded by a Latin and Ancient Greek epigraph from chapter 48 of The Satyricon of Petronius:

- Nam Sibyllam quidem Cumis ego ipse oculis meis vidi in ampulla pendere, et cum illi pueri dicerent: Σίβυλλα τί θέλεις; respondebat illa: άποθανεῖν θέλω.

Following the epigraph is a dedication (added in a 1925 republication) that reads "For Ezra Pound: il miglior fabbro". Here Eliot is both quoting line 117 of Canto XXVI of Dante's Purgatorio, the second cantica of the Divine Comedy, where Dante defines the troubadour Arnaut Daniel as "the best smith of the mother tongue", and also Pound's title of chapter 2 of his The Spirit of Romance (1910) where he translated the phrase as "the better craftsman".[26] This dedication was originally written in ink by Eliot in the 1922 Boni & Liveright edition of the poem presented to Pound; it was subsequently included in future editions.[27]

The five parts of The Waste Land are entitled:

- The Burial of the Dead

- A Game of Chess

- The Fire Sermon

- Death by Water

- What the Thunder Said

The text of the poem is followed by several pages of notes, purporting to explain his metaphors, references, and allusions. Some of these notes are helpful in interpreting the poem, but some are arguably even more puzzling, and many of the most opaque passages are left unannotated. The notes were added after Eliot's publisher requested something longer to justify printing The Waste Land in a separate book.[upper-alpha 7] Thirty years after publishing the poem with these notes, Eliot expressed his regret at "having sent so many enquirers off on a wild goose chase after Tarot cards and the Holy Grail".[29]

There is some question as to whether Eliot originally intended The Waste Land to be a collection of individual poems (additional poems were supplied to Pound for his comments on including them) or to be considered one poem with five sections.

The structure of the poem is also meant to loosely follow the vegetation myth and Holy Grail folklore surrounding the Fisher King story as outlined by Jessie Weston in her book From Ritual to Romance (1920). Weston's book was so central to the structure of the poem that it was the first text that Eliot cited in his "Notes on the Waste Land".

Style

The style of the poem is marked by the many allusions and quotations from other texts (classic and obscure; "highbrow" and "lowbrow") that Eliot peppered throughout the poem. In addition to the many "highbrow" references and quotes from poets like Baudelaire, Dante Alighieri, Shakespeare, Ovid, and Homer, as well as Wagner's libretti, Eliot also included several references to "lowbrow" genres. A good example of this is Eliot's quote from the 1912 popular song "The Shakespearian Rag" by lyricists Herman Ruby and Gene Buck.[30] There were also a number of lowbrow references in the opening section of Eliot's original manuscript (when the poem was entitled He Do The Police in Different Voices), but they were removed from the final draft after Eliot cut this original opening section.[31]

The style of the work in part grows out of Eliot's interest in exploring the possibilities of dramatic monologue. This interest dates back at least as far as "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock". The Waste Land is not a single monologue like "Prufrock". Instead, it is made up of a wide variety of voices (sometimes in monologue, dialogue, or with more than two characters speaking).

The Waste Land is notable for its seemingly disjointed structure, indicative of the Modernist style of James Joyce's Ulysses (which Eliot cited as an influence and which he read the same year that he was writing The Waste Land).[32] In the Modernist style, Eliot jumps from one voice or image to another without clearly delineating these shifts for the reader. He also includes phrases from multiple foreign languages (Latin, Greek, Italian, German, French and Sanskrit), indicative of Pound's influence.

His quotes in Sanskrit, which the author studied at Harvard in 1911-13, are particularly relevant for the definition of the final, and the most complex, section of the poem: “What the thunder said”. In particular, the three words “Datta, dayadhvam, damyata” (“Give, understand, control”) are taken from the fable of the meaning of the Thunder included in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.

In 1936, E. M. Forster wrote about The Waste Land:[33]

Let me go straight to the heart of the matter, fling my poor little hand on the table, and say what I think The Waste Land is about. It is about the fertilizing waters that arrived too late. It is a poem of horror. The earth is barren, the sea salt, the fertilizing thunderstorm broke too late. And the horror is so intense that the poet has an inhibition and is unable to state it openly.

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish ? Son of man,

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images.He cannot say 'Avaunt!' to the horror, or he would crumble into dust. Consequently, there are outworks and blind alleys all over the poem—obstacles which are due to the nature of the central emotion, and are not to be charged to the reader. The Waste Land is Mr. Eliot's greatest achievement. It intensifies the drawing-room premonitions of the earlier poems, and it is the key to what is puzzling in the prose. But, if I have its hang, it has nothing to do with the English tradition in literature, or law or order, nor, except incidentally, has the rest of his work anything to do with them either. It is just a personal comment on the universe, as individual and as isolated as Shelley's Prometheus.

... Gerard Manly Hopkins is a case in point—a poet as difficult as Mr. Eliot, and far more specialized ecclesiastically, yet however twisted his diction and pietistic his emotion, there is always a hint to the layman to come in if he can, and participate. Mr. Eliot does not want us in. He feels we shall increase the barrenness. To say he is wrong would be rash, and to pity him would be the height of impertinence, but it does seem proper to emphasize the real as opposed to the apparent difficulty of his work. He is difficult because he has seen something terrible, and (underestimating, I think, the general decency of his audience) has declined to say so plainly.

Sources

Sources from which Eliot quotes, or alludes to, include the works of Homer, Sophocles, Petronius, Virgil, Ovid,[34] Saint Augustine of Hippo, Dante, Geoffrey Chaucer, Edmund Spenser, Thomas Kyd, William Shakespeare, John Donne, Thomas Middleton, John Webster, John Milton, Andrew Marvell, Oliver Goldsmith, Gérard de Nerval, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Richard Wagner, Walt Whitman, Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Joseph Conrad, Hermann Hesse, Aldous Huxley and even the explorer Ernest Shackleton.

Eliot also makes extensive use of Scriptural writings including the Bible, the Book of Common Prayer, the Hindu Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, and the Buddha's Fire Sermon, and of cultural and anthropological studies such as Sir James Frazer's The Golden Bough and Jessie Weston's From Ritual to Romance (particularly its study of the Wasteland motif in Celtic mythology).

Eliot wrote in the original head note that "Not only the title, but the plan and a good deal of the incidental symbolism of the poem were suggested by Miss Jessie L Weston".[upper-alpha 8] The symbols Eliot employs, in addition to the Waste Land, include the Fisher King, the Tarot Deck, the Chapel perilous, and the Grail Quest.

According to Valerie Eliot, the character Marie in "The Burial of the Dead" is based on Marie Larisch, whom Eliot met at an indeterminate time and place.[35]

Parodies

Parodies of this poem have also sprung up, including one by Eliot's contemporary H. P. Lovecraft, a poem provocatively titled "Waste Paper: A Poem of Profound Insignificance".[36] Written in 1923, it is regarded by scholars like S. T. Joshi as one of his best satires.[37] Wendy Cope published a parody of The Waste Land, condensing the poem into five limericks, Waste Land Limericks, in her 1986 collection Making Cocoa for Kingsley Amis.[38][39]

Influence

Anthony Lane writes that The Waste Land is "a symphony of shocks, and like other masterworks of early modernism, it refuses to die down... The shocks have triggered aftershocks, and readers of Eliot are trapped in the quake. Escape is useless." Eliot inspired many of his contemporaries to incorporate the mythic method, the use of classic sources in a modern setting. F. Scott Fitzgerald was heavily influenced by The Waste Land when writing The Great Gatsby. Fitzgerald's novel contains a "valley of ashes" which is a kind of waste land. Gatsby was also set in 1922, the year The Waste Land was published.[40] Fitzgerald compares Gatsby to Trimalchio (a working title was Trimalchio in West Egg) who is also referenced in The Waste Land. Ernest Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises features a Fisher King character in Jake Barnes. William Faulkner's As I Lay Dying was influenced by "The Burial of the Dead". In Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow, the sound of the V-2 rocket is referred to as "what the thunder said." The titles of two of Iain M. Banks Culture novels, Consider Phlebas and Look to Windward, came straight from the Death by Water stanza. Cartoonist Martin Rowson wrote and illustrated a graphic novel pastiche of The Waste Land, in which detective Chris Marlowe encounters many of the figures in the poem.[41] The title of Evelyn Waugh's A Handful of Dust comes from the poem, and Neil Gaiman would use the phrase in his graphic novel series The Sandman. Both Genesis and Pet Shop Boys drew lyrical inspiration from the poem for "The Cinema Show" and "West End Girls", respectively,[42][43] particularly in the latter's use of different narrative voices and arcane references.[44] In Coppola's Apocalypse Now, Brando's Kurtz has copies of Weston's From Ritual to Romance and Frazer's The Golden Bough, two of Eliot's sources for the poem; he also quotes Eliot's "The Hollow Men".

Lane writes that "the more closely you map The Waste Land, the more it assumes the shape of an isthmus; so much of the past, both public and personal, streamed into its making, and so much has flowed from it ever since. When one of its most resonant quatrains is declaimed through a megaphone by Anthony Blanche, the resident dandy of Brideshead Revisited, he is obviously signaling the fashionable status of the poem, as its fame increased through the nineteen-twenties and thirties, but there's more to it than that. He is restoring, as it were, the adamantine beauty of the rhyming lines—pentameters in parenthesis, which embed the travails of the present day inside the remoteness of myth:

(And I Tiresias have foresuffered all

Enacted on the same divan or bed;

I who have sat by Thebes below the wall

And walked among the lowest of the dead.)"[45]

See also

- 1922 in poetry, year of first publication

- Eliot's essay "Tradition and the Individual Talent"

- Third man factor, which takes its name from a passage in The Waste Land

References

Notes

- Due to a line counting error Eliot footnoted some of the last lines incorrectly (with the last line being given as 433). The error was never corrected and a line count of 433 is often cited.

- Eliot's note for this line reads: "Shantih. Repeated as here, a formal ending to an Upanishad. 'The Peace which passeth understanding' is our equivalent to this word."

- For a short account of the Eliot/Quinn correspondence about The Waste Land and the history of the drafts see Eliot 1971, pp. xxii–xxix.

- Compare Eliot's 1920 poem Burbank with a Baedeker: Bleistein with a Cigar.

- For an account of the poem's publication and the politics involved see Lawrence Rainey's "The Price of Modernism: Publishing The Waste Land". The latest (and cited) version can be found in: Rainey 2005, pp. 71–101. Other versions can be found in: Bush 1991, pp. 91–111 and Eliot 2001, pp. 89–111

- Unskilled labour worth $2,800 in 1922 would cost about $125,300 in 2006.[22]

- Eliot discussing his notes: "[W]hen it came time to print The Waste Land as a little book—for the poem on its first appearance in The Dial and in The Criterion had no notes whatever—it was discovered that the poem was inconveniently short, so I set to work to expand the notes, in order to provide a few more pages of printed matter, with the result that they became the remarkable exposition of bogus scholarship that is still on view to-day."[28]

- This headnote can be found in most critical editions that include Eliot's own notes.

Citations

- Gallup 1969, pp. 29–31, 208

- Low, Valentine (9 October 2009). "Out of the waste land: TS Eliot becomes nation's favourite poet". Timesonline. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- Bennett, Alan (12 July 2009). "Margate's shrine to Eliot's muse". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- Eliot 1988, p. 451.

- Aldington 1941, p. 261.

- "TS Eliot's the Waste Land remains one of the finest reflections on mental illness ever written". The Guardian. 13 February 2018.

- Eliot 1971, p. xxii.

- "British Library".

- Eliot 1971, p. xxix.

- Ellmann, Richard (1990). A Long the Riverrun: Selected Essays. New York: Vintage. p. 69. ISBN 0679728287. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- "The Waste Land as Modernist Icon". sfu.ca.

- Hart-Davis, Rupert (1998) [First ed. published]. Halfway to Heaven: Concluding memoirs of a literary life. Stroud Gloucestershire: Sutton. pp. 54–55. ISBN 0-7509-1837-3.

- Eliot 1988, p. 498.

- Book royalty deal: Rainey 2005, p. 77

- T. S. Eliot's "London Letters" to The Dial Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, viewed 28 February 2008.

- 1922 US dollars per British pound exchange rate: Officer 2008

- The Dial's initial offer: Rainey 2005, p. 78

- The Dial magazine's announcement of award to Eliot Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, viewed 28 February 2008

- Dial purchasing books: Rainey 2005, p. 86. Rainey adds that this increased the cost to The Dial by $315.

- Eliot's 1922 salary: Gordon 2000, p. 165

- Total income from poem: Rainey 2005, p. 100

- Williamson 2020.

- Eliot 1971, p. 4.

- Hitchens, Christopher. Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere. New York: Verso, 2001: 297. ISBN 1-85984-383-2

- Eliot 1988, p. 567.

- Pound 2005, p. 33.

- Wilhelm 1990, p. 309.

- Eliot 1986, pp. 109–110.

- Wild goose chase: Eliot 1961

- North, Michael. The Waste Land: Authoritative Text, Contexts, Criticism. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2001, p. 51.

- Eliot 1971.

- MacCabe, Colin. T. S. Eliot. Tavistock: Northcote House, 2006.

- Forster 1940, pp. 91–92.

- Weidmann 2009, pp. 98–108.

- Eliot 1971, p. 126.

- "Waste Paper: A Poem of Profound Insignificance" Archived 29 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine by H. P. Lovecraft

- Marshall, Colin. "H. P. Lovecraft Writes 'Waste Paper: A Poem of Profound Insignificance', a Devastating Parody of T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land (1923)". Open Culture. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Making Cocoa for Kingsley Amis, Wendy Cope, Faber & Faber, 1986.ISBN 0-571-13747-4

- "The Waste Land: Five Limericks [by Wendy Cope]". The Best American Poetry. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Elliott, Ruth (1966). "Echoes of Eliot's The Waste Land in three modern American Novels". University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations.

- "Martin Rowson, The Wasteland – with annotations". the Guardian. 18 May 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- Macan, Edward (1997). Rocking the Classics: English Progressive Rock and the Counterculture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509887-7.

- Awde, Nick (2008). Mellotron: The Machines and the Musicians that Revolutionised Rock. Bennett & Bloom. ISBN 978-1-898948-02-5.

- "West End Girls – Pet Shop Boys". BBC Radio 2. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- Lane, Anthony (26 September 2022). "The Shocks and Aftershocks of "The Waste Land"". The New Yorker.

Cited works

- Aldington, Richard (1941). Life for Life's Sake. The Viking Press.

- Bush, Ronald (1991). T. S. Eliot. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39074-5.

- Eliot, T. S. (1961). "The Frontiers of Criticism". On Poetry and Poets. New York: Noonday Press.

- Eliot, T. S. (1971). The Waste Land: A Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts Including the Annotations of Ezra Pound. Edited and with an Introduction by Valerie Eliot. Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 0-15-694870-2.

- Eliot, T. S. (1986). "The Frontiers of Criticism". On Poetry and Poets. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-08983-6.

- Eliot, T. S. (1988). The Letters of T. S. Eliot. Vol. 1. Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

- Eliot, T. S. (2001). The Waste Land. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-97499-5.

- Forster, E. M. (1940). "T.S Eliot". Abinger Harvest (Pocket ed.). London: Edward Arnold & Co. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Gallup, Donald (1969). T. S. Eliot: A Bibliography (A Revised and Extended ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Gordon, Lyndall (2000). T. S. Eliot: An Imperfect Life. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-32093-6.

- Officer, Lawrence H. (2008). "Dollar-Pound Exchange Rate from 1791". MeasuringWorth.com.

- Pound, Ezra (2005). The Spirit of Romance. New Directions. ISBN 0-8112-1646-2.

- Rainey, Lawrence (2005). Revisiting The Waste Land. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10707-2.

- Wilhelm, James J. (1990). Ezra Pound in London and Paris, 1908–1925. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00682-X.

- Weidmann, Dirk (2009). "And I Tiresias have foresuffered all: More Than Allusions to Ovid in T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land?" (PDF). Literatura. 51 (3): 98–108.

- Williamson, Samuel H. (2020). "Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount – 1790 to Present". MeasuringWorth.Com.

Primary sources

- Eliot, T. S. (1963). Collected Poems, 1909–1962. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. ISBN 0-15-118978-1.

- The Poems of T.S. Eliot: Volume One, Collected and Uncollected Poems, edited by Christopher Ricks and Jim McCue, 2015, Faber & Faber. Includes The Waste Land: An Editorial Composite, a 678-line reading of the earliest drafts of the various parts of the poem. ISBN 978-0-571-23870-5

Secondary sources

- Ackroyd, Peter (1984). T. S. Eliot. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-11349-0.

- ( [] as of April 2023: ) Bedient, Calvin (1986). He Do the Police in Different Voices. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-04141-7.

- Bloom, Harold (2003). Genius: a Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Creative Minds. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-69129-1.

- Brooker, Jewel; Bentley, Joseph (1990). Reading the Waste Land: Modernism and the Limits of Interpretation. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-803-5.

- Claes, Paul, A Commentary on T.S. Eliot's Poem The Waste Land: The Infertility Theme and the Poet's Unhappy Marriage, Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2012.

- Drew, Elizabeth (1949). T. S. Eliot: The Design of His Poetry. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 9780684717524.

- Gish, Nancy (1988). The Waste Land: A Student's Companion to the Poem. Boston: Twayne. ISBN 0-8057-8023-8.

- Miller, James (1977). T. S. Eliot's Personal Waste Land. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01237-4.

- Moody, A. David (1994). The Cambridge Companion to T. S. Eliot. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42127-6.

- North, Michael (2000). The Waste Land (Norton Critical Editions). W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-97499-5.

- Reeves, Gareth (1994). T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf. ISBN 0-7450-0738-4.

- Southam, B. C. (1996). A Guide to the Selected Poems of T. S. Eliot. San Diego: Harcourt Brace. ISBN 0-15-600261-2.

- Sufian, Abu (July 2014). "T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land: Anticlimax of Modern Life in a Claustrophobic World". Galaxy International Multidisciplinary Research Journal. III (IV). ISSN 2278-9529.

External links

Poem itself

- An omnibus collection of T. S. Eliot's poetry at Standard Ebooks

- The Waste Land at Project Gutenberg

- Complete annotated poem

- The Waste Land at the British Library

- The Waste Land published in The Criterion (October 1922) at Internet Archive

Annotated versions

- Critical essay on The Waste Land @ the Yale Modernism Lab

- Exploring The Waste Land

- Hypertext version of The Waste Land with sources

- He Do the Police in Different Voices, a Website for Exploring Voices in The Waste Land

- The Waste Land Scripted for 44 Voices by Hedwig Gorski, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (2015) ISBN 978-1512232172

- The unedited manuscript of The Waste Land, with Ezra Pound's annotations

Recordings

- Audio of T.S. Eliot reading the poem

The Waste Land public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Waste Land public domain audiobook at LibriVox- BBC audio file. Discussion of The Waste Land and Eliot on BBC Radio 4's programme In our time.