Italians

Italians (Italian: Italiani, pronounced [itaˈljaːni]) are a nation and ethnic group native to the Italian geographical region.[40] Italians share a common culture, history, ancestry and usage of Italian language. Their predecessors differ regionally, but generally include native populations such as the Etruscans, the Rhaetians, the Ligurians, the Adriatic Veneti, and the Italic peoples, including the Latins, from which the Romans emerged and helped create and evolve the modern Italian identity.[41][42][43][44] Foreign influences include the ancient Greeks in Magna Graecia, and the Phoenicians, who had a presence in Sicily and Sardinia, the Celts, who settled in parts of the north, the Germanics and the Slavs. Legally, Italian nationals are citizens of Italy, regardless of ancestry or nation of residence (in effect, however, Italian nationality is largely based on jus sanguinis) and may be distinguished from ethnic Italians in general or from people of Italian descent without Italian citizenship and ethnic Italians living in territories adjacent to the Italian peninsula without Italian citizenship.[45][46] The Latin equivalent of the term Italian had been in use for natives of the geographical region since antiquity.[47]

Italian: Italiani | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

c. 140 million

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Italy 55,551,000[1] | |

| Brazil | 25–34 million (incl. ancestry)[3][4][5] |

| Argentina | 20–25 million (incl. ancestry)[6][7] |

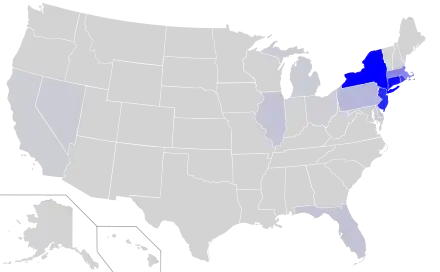

| United States | 16–23 million (incl. ancestry)[8][9][10][11] |

| France | 1–5 million (incl. ancestry)[5][12][13] |

| Venezuela | 1–5 million (incl. ancestry)[14][15][16][17] |

| Paraguay | 2.5 million (incl. ancestry)[18] |

| Colombia | 2 million (incl. ancestry)[19] |

| Canada | 1.5 million (incl. ancestry)[20] |

| Australia | 1.1 million (incl. ancestry)[21][22] |

| Uruguay | 1.0 million (incl. ancestry)[5] |

| Germany | 801,082[23] |

| Switzerland | 639,508[23] |

| Chile | 600,000[24]por |

| Peru | 500,000[25] |

| United Kingdom | 481,382[23] |

| Belgium | 451,825[26] |

| Costa Rica | 381,316[27] |

| Spain | 350,981[28] |

| Mexico | 85,000[29] |

| South Africa | 77,400[5] |

| Ecuador | 56,000[30] |

| Russia | 53,649[31] |

| Netherlands | 52,789[23] |

| Austria | 38,904[23] |

| San Marino | 33,400[32] |

| Luxembourg | 30,933 |

| Portugal | 30,819[33] |

| Ireland | 22,160 |

| Croatia | 19,636[34] |

| Sweden | 19,087 |

| Albania | 19,000[35] |

| Israel | 16,255[23] |

| Greece | 12,452[23] |

| United Arab Emirates | 10,795[23] |

| Denmark | 10,092[23] |

| Poland | 10,000[36] |

| Thailand | 10,000[37] |

| Languages | |

| Italian and other languages of Italy | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholicism[38] Minority Irreligion[39] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Corsicans, Sammarinese | |

The majority of Italian nationals are native speakers of the country's official language, Italian, a Romance language of the Indo-European language family that evolved from the Vulgar Latin, or a variety thereof, that is regional Italian. However, many of them also speak a regional or minority language native to Italy, the existence of which predates the national language.[48][49] Although there is disagreement on the total number, according to UNESCO, there are approximately 30 languages native to Italy, although many are often misleadingly referred to as "Italian dialects".[50][43][51][52]

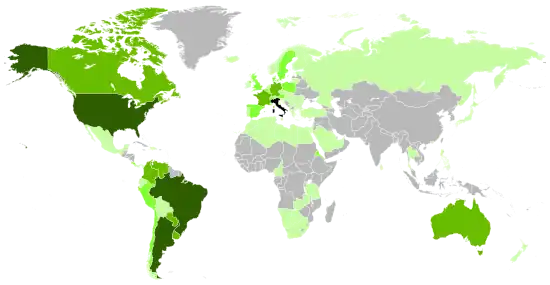

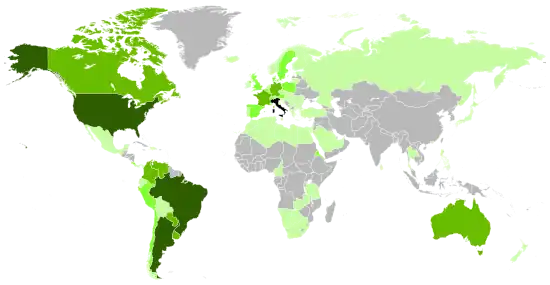

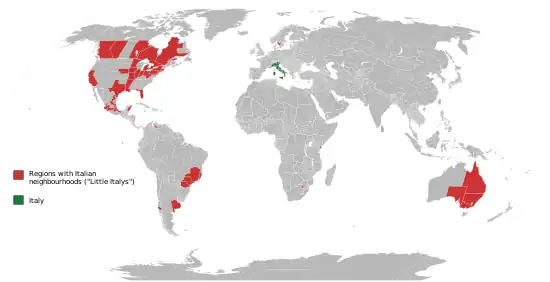

Since 2017, in addition to the approximately 55 million Italians in Italy (91% of the Italian national population),[1][53] Italian-speaking autonomous groups are found in neighboring nations; about a half million are in Switzerland,[54] as well as in France,[55] the entire population of San Marino. In addition, there are also clusters of Italian speakers in the former Yugoslavia, primarily in Istria, located between in modern Croatia and Slovenia (see: Istrian Italians), and Dalmatia, located in present-day Croatia and Montenegro (see: Dalmatian Italians). Due to the wide-ranging diaspora following Italian unification in 1861, World War I and World War II, (with over 5 million Italian citizens that live outside of Italy)[56] over 80 million people abroad claim full or partial Italian ancestry.[57] This includes about 60% of Argentina's population (Italian Argentines),[58][59] 1/3 of Uruguayans (Italian Uruguayans), 15% of Brazilians (Italian Brazilians, the largest Italian community outside Italy),[60] more than 18 million Italian Americans, and people in other parts of Europe (e.g. Italians in Germany, Italians in France and Italians in the United Kingdom), the American Continent (such as Italian Venezuelans, Italian Canadians, Italian Colombians and Italians in Paraguay, among others), Australasia (Italian Australians and Italian New Zealanders), and to a lesser extent in the Middle East (Italians in the United Arab Emirates).

Italians have influenced and contributed to fields like arts and music, science, technology, fashion, cinema, cuisine, restaurants, sports, jurisprudence, banking and business.[61][62][63][64][65] Furthermore, Italian people are generally known for their attachment to their locale, expressed in the form of either regionalism or municipalism.[66]

Name

Hypotheses for the etymology of the Latin name "Italia" are numerous.[67] One is that it was borrowed via Greek from the Oscan Víteliú 'land of calves' (cf. Lat vitulus "calf", Umb vitlo "calf").[68] Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus states this account together with the legend that Italy was named after Italus,[69] mentioned also by Aristotle[70] and Thucydides.[71]

The Latin term Italicus was used to describe "a man of Italy" as opposed to a provincial. For example, Pliny the Elder notably wrote in a letter Italicus es an provincialis? meaning "are you an Italian or a provincial?".[72] The adjective italianus, from which are derived the Italian (and also French and English) name of the Italians, is medieval and was used alternatively with Italicus during the early modern period.[73]

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, which was caused by the invasion of the Ostrogoths, the Kingdom of Italy was created. After the Lombard invasions, "Italia" was retained as the name for their kingdom, and for its successor kingdom within the Holy Roman Empire.[74]

History

Due to historic demographic shifts in the Italian peninsula throughout history, its geographical position in the center of the Mediterranean Sea, as well as Italy's regional ethnic diversity since ancient times, modern Italians are genetically diverse.[75][76] The Iron Age tribes of Italy are pre-Indo-European-speaking peoples, such as the Etruscans, Rhaetians, Camuni, Nuragics, Sicani, Elymians and the Ligures,[77] and pre-Roman Indo-European-speaking peoples, like the Celts (Gauls and Lepontii) mainly in Northern Italy, and Iapygians,[78][79] the Italic peoples throughout the peninsula (such as the Latino-Faliscans, the Osco-Umbrians, the Sicels and the Veneti), and a significant number of Greeks in Southern Italy (the so called "Magna Graecia"). Sicilians were also influenced by the Arabs, specially during the Emirate of Sicily.[80]

Italians originate mostly from these primary elements and, like the rest of Romance-speaking Southern Europe, share a common Latin heritage and history. There are also elements like the Bronze and Iron Age Middle Eastern admixture, characterized by high frequencies of Iranian and Anatolian Neolithic ancestries, including several other ancient signatures derived ultimately from the Caucasus, with a lower incidence in Northern Italy compared to Central and Southern Italy.[81][82][83] Ancient and Medieval North African admixture is also found in mainland Southern Italy and Sardinia, with the highest incidence being in Sicily.[84][80][85][86][83][82] In their admixtures, Sicilians and Southern Italians are closest to modern Greeks (as the historical region of Magna Graecia, "Greater Greece", bears witness to),[87] while Northern Italians are closest to the Spaniards and southern French.[88][89][90][91]

Prehistory

_.JPG.webp)

Italians, like most Europeans, largely descend from three distinct lineages:[92] Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, descended from populations associated with the Paleolithic Epigravettian culture;[93] Neolithic Early European Farmers who migrated from Anatolia during the Neolithic Revolution 9,000 years ago;[94] and Yamnaya Steppe pastoralists who expanded into Europe from the Pontic–Caspian steppe of Ukraine and southern Russia in the context of Indo-European migrations 5,000 years ago.[92]

The earliest modern humans inhabiting Italy are believed to have been Paleolithic peoples that may have arrived in the Italian Peninsula as early as 35,000 to 40,000 years ago. Italy is believed to have been a major Ice Age refuge from which Paleolithic humans later colonized Europe.

The Neolithic colonization of Europe from Western Asia and the Middle East beginning around 10,000 years ago reached Italy, as most of the rest of the continent although, according to the demic diffusion model, its impact was most in the southern and eastern regions of the European continent.[95]

Starting in the early Bronze Age, the first wave of migrations into Italy of Indo-European-speaking peoples occurred from Central Europe, with the appearance of the Bell Beaker culture. These were later (from the 14th century BC) followed by others that can be identified as Italo-Celts, with the appearance of the Celtic-speaking Canegrate culture[96] and the Italic-speaking Proto-Villanovan culture,[97] both deriving from the Proto-Italo-Celtic Urnfield culture. Recent DNA studies confirmed the arrival of Steppe-related ancestry in Northern Italy to at least 2000 BCE and in Central Italy by 1600 BCE, with this ancestry component increasing through time.[98][99][100]

In the Iron Age and late Bronze Age, Celtic-speaking La Tène and Hallstatt cultures spread over a large part of Italy,[101][102][103][104] with related archeological artifacts found as far south as Apulia.[105][106][107][108][109][110] Italics occupied northeastern, southern and central Italy: the "West Italic" group (including the Latins) were the first wave. They had cremation burials and possessed advanced metallurgical techniques. Major tribes included the Latins and Falisci in Lazio; the Oenotrians and Italii in Calabria; the Ausones, Aurunci and Opici in Campania; and perhaps the Veneti in Veneto and the Sicels in Sicily. They were followed, and largely displaced by the East Italic (Osco-Umbrians) group.[111]

Pre-Roman

By the beginning of the Iron Age the Etruscans emerged as the dominant civilization on the Italian peninsula. The Etruscans, whose primary home was in Etruria, expanded over a large part of Italy, covering a territory, at its greatest extent, of roughly what is now Tuscany, western Umbria, and northern Lazio,[112][113] as well as what are now the Po Valley, Emilia-Romagna, south-eastern Lombardy, southern Veneto, and western Campania.[114][115][116][117][118] On the origins of the Etruscans, the ancient authors report several hypotheses, one of which claims that the Etruscans come from the Aegean Sea. Modern archaeological and genetic research concluded that the Etruscans were autochthonous and they had a genetic profile similar to their Latin neighbors. Both Etruscans and Latins joined firmly the European cluster lacking recent admixture with Anatolia or the Eastern Mediterranean.[119][120][121][122][123][124]

The Ligures are said to have been one of the oldest populations in Italy and Western Europe,[125] possibly of Pre-Indo-European origin.[126] According to Strabo they were not Celts, but later became influenced by the Celtic culture of their neighbours, and thus are sometimes referred to as Celticized Ligurians or Celto-Ligurians.[127] Their language had affinities with both Italic (Latin and the Osco-Umbrian languages) and Celtic (Gaulish).[128][129][130] They primarily inhabited the regions of Liguria, Piedmont, northern Tuscany, western Lombardy, western Emilia-Romagna and northern Sardinia, but are believed to have once occupied an even larger portion of ancient Italy as far south as Sicily.[131][132] They were also settled in Corsica and in the Provence region along the southern coast of modern France.

During the Iron Age, prior to Roman rule, the peoples living in the area of modern Italy and the islands were:

- Etruscans (Camunni, Lepontii, Raeti);

- Sicani;

- Elymians;

- Ligures (Apuani, Bagienni, Briniates, Corsi, Friniates, Garuli, Hercates, Ilvates, Insubres, Orobii, Laevi, Lapicini, Marici, Statielli, Taurini);

- Italics (Latins, Falisci, Marsi, Umbri, Volsci, Marrucini, Osci, Aurunci, Ausones, Campanians, Paeligni, Sabines, Bruttii, Frentani, Lucani, Samnites, Pentri, Caraceni, Caudini, Hirpini, Aequi, Fidenates, Hernici, Picentes, Vestini, Morgeti, Sicels, Veneti);

- Iapygians (Messapians, Daunians, Peucetians);

- Celts (Allobroges, Ausones, Boii, Carni, Cenomani, Ceutrones, Graioceli, Lepontii, Lingones, Segusini, Senones, Salassi, Veragri, Vertamocorii);

- Greeks of Magna Graecia;

- Sardinians (Nuragic tribes), in Sardinia;

Italy was, throughout the pre-Roman period, predominantly inhabited by Italic tribes who occupied the modern regions of Lazio, Umbria, Marche, Abruzzo, Molise, Campania, Basilicata, Calabria, Apulia and Sicily. Sicily, in addition to having an Italic population in the Sicels, also was inhabited by the Sicani and the Elymians, of uncertain origin. The Veneti, most often regarded as an Italic tribe,[133] chiefly inhabited the Veneto, but extended as far east as Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Istria, and had colonies as far south as Lazio.[134][135]

Beginning in the 8th century BC, Greeks arrived in Italy and founded cities along the coast of southern Italy and eastern Sicily, which became known as Magna Graecia ("Greater Greece"). The Greeks were frequently at war with the native Italic tribes, but nonetheless managed to Hellenize and assimilate a good portion of the indigenous population located along eastern Sicily and the Southern coasts of the Italian mainland.[136][137] According to Beloch the number of Greek citizens in south Italy at its greatest extent reached only 80,000–90,000, while the local people subjected by the Greeks were between 400,000 and 600,000.[138][139] By the 4th and 3rd century BC, Greek power in Italy was challenged and began to decline, and many Greeks were pushed out of peninsular Italy by the native Oscan, Brutti and Lucani tribes.[140]

The Gauls crossed the Alps and invaded northern Italy in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, settling in the area that became known as Cisalpine Gaul ("Gaul on this side of the Alps"). Although named after the Gauls, the region was mostly inhabited by indigenous tribes, namely the Ligures, Etruscans, Veneti and Euganei. Estimates by Beloch and Brunt suggest that in the 3rd century BC the Gaulish settlers of north Italy numbered between 130,000 and 140,000 out of a total population of about 1.4 million.[139][141] The Northern half of Cisalpine Gaul was already inhabited by the Celtic Lepontii since the Bronze Age. Speaking about the Alpine region, the Greek historian Strabo, wrote:

The Alps are inhabited by numerous nations, but all Keltic with the exception of the Ligurians, and these, though of a different race, closely resemble them in their manner of life.[127]

According to Pliny and Livy, after the invasion of the Gauls, some of the Etruscans living in the Po Valley sought refuge in the Alps and became known as the Raeti.[142][143] The Raeti inhabited the region of Trentino-Alto Adige, as well as eastern Switzerland and Tyrol in western Austria. The Ladins of north-eastern Italy and the Romansh people of Switzerland are said to be descended from the Raeti.[144]

Roman times through Middle Ages

.jpg.webp)

The Romans—who according to legend originally consisted of three ancient tribes: Latins, Sabines and Etruscans[146]—would go on to conquer the whole Italian peninsula. During the Roman period hundreds of cities and colonies were established throughout Italy, including Florence, Turin, Como, Pavia, Padua, Verona, Vicenza, Trieste and many others. Initially many of these cities were colonized by Latins, but later also included colonists belonging to the other Italic tribes who had become Latinized and joined to Rome. After the Roman conquest of Italy "the whole of Italy had become Latinized".[147] After the Roman conquest of Cisalpine Gaul and the widespread confiscations of Gallic territory, some of the Gaulish population was either killed or expelled.[148][149] Many colonies were established by the Romans in the former Gallic territory of Cisalpine Gaul, which was then settled by Roman and Italic people. These colonies included Bologna, Modena, Reggio Emilia, Parma, Piacenza, Cremona and Forlì. According to Strabo:

The Cispadane peoples occupy all that country which is encircled by the Apennine Mountains towards the Alps as far as Genua and Sabata. The greater part of the country used to be occupied by the Boii, Ligures, Senones, and Gaesatae; but since the Boii have been driven out, and since both the Gaesatae and the Senones have been annihilated, only the Ligurian tribes and the Roman colonies are left.[149]

The Boii, the most powerful and numerous of the Gallic tribes, were expelled by the Romans after 191 BC and settled in Bohemia, while the Insubres still lived in Mediolanum in the 1st century BC.[150]

Augustus created for the first time an administrative region called Italia with inhabitants called "Italicus populus", stretching from the Alps to Sicily: for this reason historians like Emilio Gentile called him Father of Italians.[145] Population movement and exchange among people from different regions was not uncommon during the Roman period. Latin colonies were founded at Ariminum in 268 and at Firmum in 264,[151] while large numbers of Picentes, who previously inhabited the region, were moved to Paestum and settled along the river Silarus in Campania. Between 180 and 179 BC, 47,000 Ligures belonging to the Apuani tribe were removed from their home along the modern Ligurian-Tuscan border and deported to Samnium, an area corresponding to inland Campania, while Latin colonies were established in their place at Pisa, Lucca and Luni.[152] Such population movements contributed to the rapid Romanization and Latinization of Italy.[153]

.png.webp)

A large Germanic confederation of Sciri, Heruli, Turcilingi and Rugians, led by Odoacer, invaded and settled Italy in 476.[154] They were preceded by Alemanni, including 30,000 warriors with their families, who settled in the Po Valley in 371,[155] and by Burgundians who settled between Northwestern Italy and Southern France in 443.[156] The Germanic tribe of the Ostrogoths led by Theoderic the Great conquered Italy and presented themselves as upholders of Latin culture, mixing Roman culture together with Gothic culture, in order to legitimize their rule amongst Roman subjects who had a long-held belief in the superiority of Roman culture over foreign "barbarian" Germanic culture.[157] Since Italy had a population of several million, the Goths did not constitute a significant addition to the local population.[158] At the height of their power, there were several thousand Ostrogoths in a population of 6 or 7 million.[156][159] Before them, Radagaisus led tens of thousands of Goths in Italy in 406, though figures may be too high as ancient sources routinely inflated the numbers of tribal invaders.[160] After the Gothic War, which devastated the local population, the Ostrogoths were defeated. Nevertheless, according to Roman historian Procopius of Caesarea, the Ostrogothic population was allowed to live peacefully in Italy with their Rugian allies under Roman sovereignty.[161]

But in the sixth century, another Germanic tribe known as the Longobards invaded Italy, which in the meantime had been reconquered by the East Roman or Byzantine Empire. The Longobards were a small minority compared to the roughly four million people in Italy at the time.[162] They were later followed by the Bavarians and the Franks, who conquered and ruled most of Italy. Some groups of Slavs settled in parts of the northern Italian peninsula between the 7th and the 8th centuries,[163][164][165] while Bulgars led by Alcek settled in Sepino, Bojano and Isernia. These Bulgars preserved their speech and identity until the late 8th century.[166]

Following Roman rule, Sicily, Corsica and Sardinia were conquered by the Vandals, then by the Ostrogoths, and finally by the Byzantines. At one point, Sardinia grew increasingly autonomous from the Byzantine rule to the point of organizing itself into four sovereign Kingdoms, known as "Judicates", that would last until the Aragonese conquest in the 15th century. Corsica came under the influence of the Kingdom of the Lombards and later under the maritime Republics of Pisa and Genoa. In 687, Sicily became the Byzantine Theme of Sicily; during the course of the Arab–Byzantine wars, Sicily gradually became the Emirate of Sicily (831–1072). Later, a series of conflicts with the Normans would bring about the establishment of the County of Sicily, and eventually the Kingdom of Sicily. The Lombards of Sicily (not to be confused with the Longobards), coming from Northern Italy, settled in the central and eastern part of Sicily. After the marriage between the Norman Roger I of Sicily and Adelaide del Vasto, descendant of the Aleramici family, many Northern Italian colonisers (known collectively as Lombards) left their homeland, in the Aleramici's possessions in Piedmont and Liguria (then known as Lombardy), to settle on the island of Sicily.[167][168]

Before them, other Lombards arrived in Sicily, with an expedition departed in 1038, led by the Byzantine commander George Maniakes,[169] which for a very short time managed to snatch Messina and Syracuse from Arab rule. The Lombards who arrived with the Byzantines settled in Maniace, Randazzo and Troina, while a group of Genoese and other Lombards from Liguria settled in Caltagirone.[170]

Renaissance to the modern era

From the 11th century on, Italian cities began to grow rapidly in independence and importance. They became centres of political life, banking, and foreign trade. Some became wealthy, and many, including Florence, Rome, Genoa, Milan, Pisa, Siena and Venice, grew into nearly independent city-states and maritime republics. Each had its own foreign policy and political life. They all resisted, with varying degrees of success, the efforts of noblemen, emperors, and larger foreign powers to control them.

By the 12th century, Swabian kings granted immigrants from northern Italy (particularly Piedmont, Lombardy and Liguria), Latium and Tuscany in central Italy, and French regions of Normandy, Provence and Brittany (all collectively known as Lombards.)[176][177] settlement into Sicily, re-establishing the Latin element into the island, a legacy which can be seen in the many Gallo-Italic dialects and towns found in the interior and western parts of Sicily, brought by these settlers.[178] It is believed that the Lombard immigrants in Sicily over a couple of centuries were a total of about 200,000.[179][180][181] An estimated 20,000 Swabians and 40,000 Normans settled in the southern half of Italy during this period.[182] Additional Tuscan migrants settled in Sicily after the Florentine conquest of Pisa in 1406.[183] The emergence of identifiable Italian dialects from Vulgar Latin, and as such the possibility of a specifically "Italian" ethnic identity, has no clear-cut date, but began in roughly the 12th century. Modern standard Italian derives from the written vernacular of Tuscan writers of the 12th century. The recognition of Italian vernaculars as literary languages in their own right began with De vulgari eloquentia, an essay written by Dante Alighieri at the beginning of the 14th century.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, some Italian city-states ranked among the most important powers of Europe. Venice, in particular, had become a major maritime power, and the city-states as a group acted as a conduit for goods from the Byzantine and Islamic empires. In this capacity, they provided great impetus to the developing Renaissance, began in Florence in the 14th century,[184] and led to an unparalleled flourishing of the arts, literature, music, and science.

Substantial migrations of Lombards to Naples, Rome and Palermo, continued in the 16th and 17th centuries, driven by the constant overcrowding in the north.[185][186] Beside that, minor but significant settlements of Slavs (the so-called Schiavoni) and Arbereshe in Italy have been recorded, while Scottish soldiers - the Garde Ecossaise - who served the French King, Francis I, settled in the mountains of Piedmont.[187][188]

The geographical and cultural proximity with Southern Italy pushed Albanians to cross the Strait of Otranto, especially after Skanderbeg's death and the conquest of the Balkans by the Ottomans. In defense of the Christian religion and in search of soldiers loyal to the Spanish crown, Alfonso V of Aragon, also king of Naples, invited Arbereshe soldiers to move to Italy with their families. In return the king guaranteed to Albanians lots of land and a favourable taxation.

Arbereshe and Schiavoni were used to repopulate abandoned villages or villages whose population had died in earthquakes, plagues and other catastrophes. Albanian soldiers were also used to quell rebellions in Calabria. Slavic colonies were established in eastern Friuli,[189] Sicily[190] and Molise (Molise Croats).[191]

Between the Late Middle Ages and the early modern period, there were several waves of immigration of Albanians into Italy, in addition to another in the 20th century.[192] The descendants of these Albanian emigrants, many still retaining the Albanian language, the Arbëresh dialect, have survived throughout southern Italy, numbering about 260,000 people,[193] with roughly 80,000 to 100,000 speaking the Albanian language.[194][195]

Culture

Italy is considered one of the birthplaces of Western civilization[196] and a cultural superpower.[197] Italian culture is the culture of the Italians and is incredibly diverse spanning the entirety of the Italian peninsula and the islands of Sardinia and Sicily. Italy has been the starting point of phenomena of international impact such as the Roman Republic, Roman Empire, the Roman Catholic Church, the Maritime republics, Romanesque art, Scholasticism, the Renaissance, the Age of Discovery, Mannerism, the Scientific revolution,[198] the Baroque, Neoclassicism, the Risorgimento, Fascism,[199] and European integration.

Italy also became a seat of great formal learning in 1088 with the establishment of the University of Bologna, the oldest university in continuous operation, and the first university in the sense of a higher-learning and degree-awarding institute, as the word universitas was coined at its foundation.[200][201][202][203] Many other Italian universities soon followed. For example, the Schola Medica Salernitana, in southern Italy, was the first medical school in Europe.[204] These great centres of learning presaged the Rinascimento: the European Renaissance began in Italy and was fueled throughout Europe by Italian painters, sculptors, architects, scientists, literature masters and music composers. Italy continued its leading cultural role through the Baroque period and into the Romantic period, when its dominance in painting and sculpture diminished but the Italians re-established a strong presence in music.

Due to comparatively late national unification, and the historical autonomy of the regions that comprise the Italian peninsula, many traditions and customs of the Italians can be identified by their regions of origin. Despite the political and social isolation of these regions, Italy's contributions to the cultural and historical heritage of the Western world remain immense. Famous elements of Italian culture are its opera and music, its iconic gastronomy and food, which are commonly regarded as amongst the most popular in the world,[205] its cinema (with filmmakers such as Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Mario Monicelli, Sergio Leone, etc.), its collections of priceless works of art and its fashion (Milan and Florence are regarded as some of the few fashion capitals of the world).

Traditions of Italy are sets of traditions, beliefs, values, and customs that belongs within the culture of Italian people. These traditions have influenced life in Italy for centuries, and are still practiced in modern times. Italian traditions are directly connected to Italy's ancestors, which says even more about Italian history. Folklore of Italy refers to the folklore and urban legends of Italy. Within the Italian territory, various peoples have followed one another over time, each of which has left its mark on current culture. Some tales also come from Christianization, especially those concerning demons, which are sometimes recognized by Christian demonology. Italian folklore also includes Italian folk dance, Italian folk music and folk heroes.

Italian cuisine is a Mediterranean cuisine[206] consisting of the ingredients, recipes and cooking techniques developed across the Italian Peninsula since antiquity, and later spread around the world together with waves of Italian diaspora.[207][208][209] Italian cuisine includes deeply rooted traditions common to the whole country, as well as all the regional gastronomies, different from each other, especially between the north, the centre and the south of Italy, which are in continuous exchange.[210][211][212] Many dishes that were once regional have proliferated with variations throughout the country.[213][214] Italian cuisine offers an abundance of taste, and has influenced several other cuisines around the world, chiefly that of the United States.[215] The most popular dishes and recipes, over the centuries, have often been created by ordinary people more so than by chefs, which is why many Italian recipes are suitable for home and daily cooking, respecting regional specificities, privileging only raw materials and ingredients from the region of origin of the dish and preserving its seasonality.[216][217][218]

Philosophy

Over the ages, Italian literature had a vast influence on Western philosophy, beginning with the Greeks and Romans, and going onto Renaissance, The Enlightenment and modern philosophy. Italian Medieval philosophy was mainly Christian, and included several important philosophers and theologians such as St Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas was the student of Albert the Great, a brilliant Dominican experimentalist, much like the Franciscan, Roger Bacon of Oxford in the 13th century. Aquinas reintroduced Aristotelian philosophy to Christianity. He believed that there was no contradiction between faith and secular reason. He believed that Aristotle had achieved the pinnacle in the human striving for truth and thus adopted Aristotle's philosophy as a framework in constructing his theological and philosophical outlook. He was a professor at the prestigious University of Paris.

Italy was also affected by the Enlightenment, a movement which was a consequence of the Renaissance and changed the road of Italian philosophy.[219] Followers of the group often met to discuss in private salons and coffeehouses, notably in the cities of Milan, Rome and Venice. Cities with important universities such as Padua, Bologna and Naples, however, also remained great centres of scholarship and the intellect, with several philosophers such as Giambattista Vico (1668–1744) (who is widely regarded as being the founder of modern Italian philosophy)[220] and Antonio Genovesi.[219] Italian society also dramatically changed during the Enlightenment, with rulers such as Leopold II of Tuscany abolishing the death penalty. The church's power was significantly reduced, and it was a period of great thought and invention, with scientists such as Alessandro Volta and Luigi Galvani discovering new things and greatly contributing to Western science.[219] Cesare Beccaria was also one of the greatest Italian Enlightenment writers and is now considered one of the fathers of classical criminal theory as well as modern penology.[221] Beccaria is famous for his masterpiece On Crimes and Punishments (1764), a treatise (later translated into 22 languages) that served as one of the earliest prominent condemnations of torture and the death penalty and thus a landmark work in anti-death penalty philosophy.[219]

Some of the most prominent philosophies and ideologies in Italy during the late 19th and 20th centuries include anarchism, communism, socialism, futurism, fascism, and Christian democracy. Antonio Rosmini, instead, was the founder of Italian idealism. Both futurism and fascism (in its original form, now often distinguished as Italian fascism) were developed in Italy at this time. From the 1920s to the 1940s, Italian Fascism was the official philosophy and ideology of the Italian government led by Benito Mussolini. Giovanni Gentile was one of the most significant 20th-century Idealist/Fascist philosophers. Meanwhile, anarchism, communism, and socialism, though not originating in Italy, took significant hold in Italy during the early 20th century, with the country producing numerous significant Italian anarchists, socialists, and communists. In addition, anarcho-communism first fully formed into its modern strain within the Italian section of the First International.[222] Antonio Gramsci remains an important philosopher within Marxist and communist theory, credited with creating the theory of cultural hegemony.

Early Italian feminists include Sibilla Aleramo, Alaide Gualberta Beccari, and Anna Maria Mozzoni, though proto-feminist philosophies had previously been touched upon by earlier Italian writers such as Christine de Pizan, Moderata Fonte, and Lucrezia Marinella. Italian physician and educator Maria Montessori is credited with the creation of the philosophy of education that bears her name, an educational philosophy now practiced throughout the world.[223] Giuseppe Peano was one of the founders of analytic philosophy and contemporary philosophy of mathematics. Recent analytic philosophers include Carlo Penco, Gloria Origgi, Pieranna Garavaso and Luciano Floridi.[224]

Literature

Formal Latin literature began in 240 BC, when the first stage play was performed in Rome.[226] Latin literature was, and still is, highly influential in the world, with numerous writers, poets, philosophers, and historians, such as Pliny the Elder, Pliny the Younger, Virgil, Horace, Propertius, Ovid and Livy. The Romans were also famous for their oral tradition, poetry, drama and epigrams.[227] In early years of the 13th century, St. Francis of Assisi was considered the first Italian poet by literary critics, with his religious song Canticle of the Sun.[228]

Italian literature may be unearthed back to the Middle Ages, with the most significant poets of the period being Dante Alighieri, Petrarch, and Giovanni Boccaccio. During the Renaissance, humanists such as Leonardo Bruni, Coluccio Salutati and Niccolò Machiavelli were great collectors of antique manuscripts. Many worked for the organized Church and were in holy orders (like Petrarch), while others were lawyers and chancellors of Italian cities, like Petrarch's disciple, Salutati, the Chancellor of Florence, and thus had access to book copying workshops.

In the 18th century, the political condition of the Italian states began to improve, and philosophers disseminated their writings and ideas throughout Europe during the Age of Enlightenment. Apostolo Zeno and Metastasio are two of the notable figures of the age. Carlo Goldoni, a Venetian playwright and librettist, created the comedy of character. The leading figure of the 18th-century Italian literary revival was Giuseppe Parini.

One of the most remarkable poets of the early 19th and 20th century writers was Giacomo Leopardi, who is widely acknowledged to be one of the most radical and challenging thinkers of the 19th century.[230][231] The main instigator of the reform was the Italian poet and novelist Alessandro Manzoni, notable for being the author of the historical novel I promessi sposi (The Betrothed, 1827–1842). Italo Svevo, the author of La coscienza di Zeno (1923), and Luigi Pirandello (winner of the 1934 Nobel Prize in Literature), who explored the shifting nature of reality in his prose fiction and such plays as Sei personaggi in cerca d'autore (Six Characters in Search of an Author, 1921). Federigo Tozzi and Giuseppe Ungaretti were well-known novelists, critically appreciated only in recent years, and regarded one of the forerunners of existentialism in the European novel.

Modern literary figures and Nobel laureates are Gabriele D'Annunzio from 1889 to 1910, nationalist poet Giosuè Carducci in 1906, realist writer Grazia Deledda in 1926, modern theatre author Luigi Pirandello in 1936, short stories writer Italo Calvino in 1960, poets Salvatore Quasimodo in 1959 and Eugenio Montale in 1975, Umberto Eco in 1980, and satirist and theatre author Dario Fo in 1997.[232]

Theatre

Italian theatre originates from the Middle Ages, with its background dating back to the times of the ancient Greek colonies of Magna Graecia, in Southern Italy,[233] the theatre of the Italic peoples[234] and the theatre of ancient Rome. It can therefore be assumed that there were two main lines of which the ancient Italian theatre developed in the Middle Ages. The first, consisting of the dramatization of Catholic liturgies and of which more documentation is retained, and the second, formed by pagan forms of spectacle such as the staging for city festivals, the court preparations of the jesters and the songs of the troubadours.[235] The Renaissance theatre marked the beginning of the modern theatre due to the rediscovery and study of the classics, the ancient theatrical texts were recovered and translated, which were soon staged at the court and in the curtensi halls, and then moved to real theatre. In this way the idea of theatre came close to that of today: a performance in a designated place in which the public participates. In the late 15th century two cities were important centers for the rediscovery and renewal of theatrical art: Ferrara and Rome. The first, vital center of art in the second half of the fifteenth century, saw the staging of some of the most famous Latin works by Plautus, rigorously translated into Italian.[236]

During the 16th century and on into the 18th century, Commedia dell'arte was a form of improvisational theatre, and it is still performed today. Travelling troupes of players would set up an outdoor stage and provide amusement in the form of juggling, acrobatics and, more typically, humorous plays based on a repertoire of established characters with a rough storyline, called canovaccio. Plays did not originate from written drama but from scenarios called lazzi, which were loose frameworks that provided the situations, complications, and outcome of the action, around which the actors would improvise. The characters of the commedia usually represent fixed social types and stock characters, each of which has a distinct costume, such as foolish old men, devious servants, or military officers full of false bravado. The main categories of these characters include servants, old men, lovers, and captains.[240]

The Ballet dance genre also originated in Italy. It began during the Italian Renaissance court as an outgrowth of court pageantry,[241] where aristocratic weddings were lavish celebrations. Court musicians and dancers collaborated to provide elaborate entertainment for them.[242] At first, ballets were woven in to the midst of an opera to allow the audience a moment of relief from the dramatic intensity. By the mid-seventeenth century, Italian ballets in their entirety were performed in between the acts of an opera. Over time, Italian ballets became part of theatrical life: ballet companies in Italy's major opera houses employed an average of four to twelve dancers; in 1815 many companies employed anywhere from eighty to one hundred dancers.[243]

Noteworthy Italian theater actors and playwrights are Jacopone da Todi, Angelo Beolco, Isabella Andreini, Carlo Goldoni, Eduardo Scarpetta, Ettore Petrolini Eleonora Duse, Eduardo De Filippo, Carmelo Bene and Giorgio Strehler.

Cuisine

Italian cuisine is a Mediterranean cuisine[206] consisting of the ingredients, recipes and cooking techniques developed across the Italian Peninsula since antiquity, and later spread around the world together with waves of Italian diaspora.[244][245][246] Italian cuisine includes deeply rooted traditions common to the whole country, as well as all the regional gastronomies, different from each other, especially between the north, the centre and the south of Italy, which are in continuous exchange.[247][248][249] Many dishes that were once regional have proliferated with variations throughout the country.[250][251] Italian cuisine offers an abundance of taste, and has influenced several other cuisines around the world, chiefly that of the United States.[252] Italian cuisine has developed through centuries of social and political changes, it has its roots in ancient Rome.[253]

One of the main characteristics of Italian cuisine is its simplicity, with many dishes made up of few ingredients, and therefore Italian cooks often rely on the quality of the ingredients, rather than the complexity of preparation.[254][255] The most popular dishes and recipes, over the centuries, have often been created by ordinary people more so than by chefs, which is why many Italian recipes are suitable for home and daily cooking, respecting regional specificities, privileging only raw materials and ingredients from the region of origin of the dish and preserving its seasonality.[256][257][258]

Noteworthy Italian chefs are Bartolomeo Scappi, Gualtiero Marchesi, Lidia Bastianich, Antonio Carluccio, Cesare Casella, Carlo Cracco, Antonino Cannavacciuolo, Gino D'Acampo, Gianfranco Chiarini, Massimiliano Alajmo, Massimo Bottura and Bruno Barbieri.

Visual art

The history of Italian visual arts is significant to the history of Western painting. Roman art was influenced by Greece and can in part be taken as a descendant of ancient Greek painting. Roman painting does have its own unique characteristics. The only surviving Roman paintings are wall paintings, many from villas in Campania, in Southern Italy. Such paintings can be grouped into four main "styles" or periods[259] and may contain the first examples of trompe-l'œil, pseudo-perspective, and pure landscape.[260]

Panel painting becomes more common during the Romanesque period, under the heavy influence of Byzantine icons. Towards the middle of the 13th century, Medieval art and Gothic painting became more realistic, with the beginnings of interest in the depiction of volume and perspective in Italy with Cimabue and then his pupil Giotto. From Giotto onwards, the treatment of composition in painting became much more free and innovative.

The Italian Renaissance is said by many to be the golden age of painting; roughly spanning the 14th through the mid-17th centuries with a significant influence also out of the borders of modern Italy. In Italy artists like Paolo Uccello, Fra Angelico, Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, Andrea Mantegna, Filippo Lippi, Giorgione, Tintoretto, Sandro Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giovanni Bellini, and Titian took painting to a higher level through the use of perspective, the study of human anatomy and proportion, and through their development of refined drawing and painting techniques. Michelangelo was active as a sculptor from about 1500 to 1520; works include his David, Pietà, Moses. Other Renaissance sculptors include Lorenzo Ghiberti, Luca Della Robbia, Donatello, Filippo Brunelleschi and Andrea del Verrocchio.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the High Renaissance gave rise to a stylised art known as Mannerism. In place of the balanced compositions and rational approach to perspective that characterised art at the dawn of the 16th century, the Mannerists sought instability, artifice, and doubt. The unperturbed faces and gestures of Piero della Francesca and the calm Virgins of Raphael are replaced by the troubled expressions of Pontormo and the emotional intensity of El Greco.

In the 17th century, among the greatest painters of Italian Baroque are Caravaggio, Annibale Carracci, Artemisia Gentileschi, Mattia Preti, Carlo Saraceni and Bartolomeo Manfredi. Subsequently, in the 18th century, Italian Rococo was mainly inspired by French Rococo, since France was the founding nation of that particular style, with artists such as Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and Canaletto. Italian Neoclassical sculpture focused, with Antonio Canova's nudes, on the idealist aspect of the movement.

In the 19th century, major Italian Romantic painters were Francesco Hayez, Giuseppe Bezzuoli and Francesco Podesti. Impressionism was brought from France to Italy by the Macchiaioli, led by Giovanni Fattori, and Giovanni Boldini; Realism by Gioacchino Toma and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo. In the 20th century, with Futurism, primarily through the works of Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla, Italy rose again as a seminal country for artistic evolution in painting and sculpture. Futurism was succeeded by the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, who exerted a strong influence on the Surrealists and generations of artists to follow like Bruno Caruso and Renato Guttuso.

Architecture

Italians are known for their significant architectural achievements,[261] such as the construction of arches, domes and similar structures during ancient Rome, the founding of the Renaissance architectural movement in the late-14th to 16th centuries, and being the homeland of Palladianism, a style of construction which inspired movements such as that of Neoclassical architecture, and influenced the designs which noblemen built their country houses all over the world, notably in the UK, Australia and the US during the late 17th to early 20th centuries. Several of the finest works in Western architecture, such as the Colosseum, the Milan Cathedral and Florence cathedral, the Leaning Tower of Pisa and the building designs of Venice are found in Italy.

Italian architecture has also widely influenced the architecture of the world. British architect Inigo Jones, inspired by the designs of Italian buildings and cities, brought back the ideas of Italian Renaissance architecture to 17th-century England, being inspired by Andrea Palladio.[262] Additionally, Italianate architecture, popular abroad since the 19th century, was used to describe foreign architecture which was built in an Italian style, especially modelled on Renaissance architecture.

Italian modern and contemporary architecture refers to architecture in Italy during 20th and 21st centuries. During the Fascist period the so-called "Novecento movement" flourished, with figures such as Gio Ponti, Peter Aschieri, Giovanni Muzio. This movement was based on the rediscovery of imperial Rome. Marcello Piacentini, who was responsible for the urban transformations of several cities in Italy, and remembered for the disputed Via della Conciliazione in Rome, devised a form of "simplified Neoclassicism".

The fascist architecture (shown perfectly in the EUR buildings) was followed by the Neoliberty style (seen in earlier works of Vittorio Gregotti) and Brutalist architecture (Torre Velasca in Milan group BBPR, a residential building via Piagentina in Florence, Leonardo Savioli and works by Giancarlo De Carlo).

Music

From folk music to classical, music has always played an important role in Italian culture. Instruments associated with classical music, including the piano and violin, were invented in Italy, and many of the prevailing classical music forms, such as the symphony, concerto, and sonata, can trace their roots back to innovations of 16th- and 17th-century Italian music. Italians invented many of the musical instruments, including the piano and violin.

Most notable Italians composers include the Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Claudio Monteverdi, the Baroque composers Scarlatti, Corelli and Vivaldi, the Classical composers Paganini and Rossini, and the Romantic composers Verdi and Puccini, whose operas, including La bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, and Turandot, are among the most frequently worldwide performed in the standard repertoire.[263][264] Modern Italian composers such as Berio and Nono proved significant in the development of experimental and electronic music. While the classical music tradition still holds strong in Italy, as evidenced by the fame of its innumerable opera houses, such as La Scala of Milan and San Carlo of Naples, and performers such as the pianist Maurizio Pollini and the late tenor Luciano Pavarotti, Italians have been no less appreciative of their thriving contemporary music scene.

Italians are amply known as the mothers of opera.[266] Italian opera was believed to have been founded in the early 17th century, in Italian cities such as Mantua and Venice.[266] Later, works and pieces composed by native Italian composers of the 19th and early 20th centuries, such as Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi and Puccini, are among the most famous operas ever written and today are performed in opera houses across the world. La Scala operahouse in Milan is also renowned as one of the best in the world. Famous Italian opera singers include Enrico Caruso and Alessandro Bonci.

.jpg.webp)

Introduced in the early 1920s, jazz took a particularly strong foothold among Italians, and remained popular despite the xenophobic cultural policies of the Fascist regime. Today, the most notable centres of jazz music in Italy include Milan, Rome, and Sicily. Later, Italy was at the forefront of the progressive rock movement of the 1970s, with bands like PFM and Goblin. Italy was also an important country in the development of disco and electronic music, with Italo disco, known for its futuristic sound and prominent usage of synthesizers and drum machines, being one of the earliest electronic dance genres, as well as European forms of disco aside from Euro disco (which later went on to influence several genres such as Eurodance and Nu-disco).

Producers and songwriters such as Giorgio Moroder, who won three Academy Awards for his music, were highly influential in the development of EDM (electronic dance music). Today, Italian pop music is represented annually with the Sanremo Music Festival, which served as inspiration for the Eurovision song contest, and the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto. Singers such as pop diva Mina, classical crossover artist Andrea Bocelli, Grammy winner Laura Pausini, and European chart-topper Eros Ramazzotti have attained international acclaim.

Cinema

Since the development of the Italian film industry in the early 1900s, Italian filmmakers and performers have, at times, experienced both domestic and international success, and have influenced film movements throughout the world.[269][270] The history of Italian cinema began a few months after the Lumière brothers began motion picture exhibitions.[271][272] The first Italian director is considered to be Vittorio Calcina, a collaborator of the Lumière Brothers, who filmed Pope Leo XIII in 1896.[273] In the 1910s the Italian film industry developed rapidly.[274] Cabiria, a 1914 Italian epic film directed by Giovanni Pastrone, is considered the most famous Italian silent film.[274][275] It was also the first film in history to be shown in the White House.[276][277][278] The oldest European avant-garde cinema movement, Italian futurism, took place in the late 1910s.[279]

After a period of decline in the 1920s, the Italian film industry was revitalized in the 1930s with the arrival of sound film. A popular Italian genre during this period, the Telefoni Bianchi, consisted of comedies with glamorous backgrounds.[280] Calligrafismo was instead in a sharp contrast to Telefoni Bianchi-American style comedies and is rather artistic, highly formalistic, expressive in complexity and deals mainly with contemporary literary material.[281]

A new era took place at the end of World War II, with the Italian film that was widely recognised and exported until an artistic decline around the 1980s.[285] Notable Italian film directors from this period include Vittorio De Sica, Federico Fellini, Sergio Leone, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Luchino Visconti, Michelangelo Antonioni, Dussio Tessari and Roberto Rossellini; some of these are recognised among the greatest and most influential filmmakers of all time.[286][287] Movies include world cinema treasures such as Bicycle Thieves, La dolce vita, 8½, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, and Once Upon a Time in the West. The mid-1940s to the early 1950s was the heyday of neorealist films, reflecting the poor condition of post-war Italy.[288] Actresses such as Sophia Loren, Giulietta Masina and Gina Lollobrigida achieved international stardom during this period.[280]

Since the early 1960s they also popularized a large number of genres and subgenres, such as Peplum, Macaroni Combat, Musicarello, Poliziotteschi and Commedia sexy all'italiana.[289] The Spaghetti Western achieved popularity in the mid-1960s, peaking with Sergio Leone's Dollars Trilogy, which featured enigmatic scores by composer Ennio Morricone. Erotic Italian thrillers, or Giallos, produced by directors such as Mario Bava and Dario Argento in the 1970s, influenced the horror genre worldwide. In recent years, directors such as Ermanno Olmi, Bernardo Bertolucci, Giuseppe Tornatore, Gabriele Salvatores, Roberto Benigni, Matteo Garrone, Paolo Sorrentino and Luca Guadagnino brought critical acclaim back to Italian cinema.

The Venice International Film Festival, awarding the "Golden Lion" and held annually since 1932, is the oldest film festival in the world and one of the "Big Three" alongside Cannes and Berlin.[290][291] The country is also famed for its prestigious David di Donatello. Italy is the most awarded country at the Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film, with 14 awards won, 3 Special Awards and 28 nominations.[292] As of 2016, Italian films have also won 12 Palmes d'Or (the second-most of any country),[293] 11 Golden Lions[294] and 7 Golden Bears.[295] The list of the 100 Italian films to be saved was created with the aim to report "100 films that have changed the collective memory of the country between 1942 and 1978".[296]

Fashion and design

Italian fashion has a long tradition. Milan, Florence and Rome are Italy's main fashion capitals. According to Top Global Fashion Capital Rankings 2013 by Global Language Monitor, Rome ranked sixth worldwide when Milan was twelfth. Previously, in 2009, Milan was declared as the "fashion capital of the world" by Global Language Monitor itself.[297] Currently, Milan and Rome, annually compete with other major international centres, such as Paris, New York, London, and Tokyo.

The Italian fashion industry is one of the country's most important manufacturing sectors. The majority of the older Italian couturiers are based in Rome. However, Milan is seen as the fashion capital of Italy because many well-known designers are based there and it is the venue for the Italian designer collections. Major Italian fashion labels, such as Gucci, Armani, Prada, Versace, Valentino, Dolce & Gabbana, Missoni, Fendi, Moschino, Max Mara, Trussardi, Benetton, and Ferragamo, to name a few, are regarded as among the finest fashion houses in the world.

.jpg.webp)

Accessory and jewelry labels, such as Bulgari, Luxottica, Buccellati have been founded in Italy and are internationally acclaimed, and Luxottica is the world's largest eyewear company. Also, the fashion magazine Vogue Italia, is considered one of the most prestigious fashion magazines in the world.[298] The talent of young, creative fashion is also promoted, as in the ITS young fashion designer competition in Trieste.[299]

Italy is also prominent in the field of design, notably interior design, architectural design, industrial design, and urban design. The country has produced some well-known furniture designers, such as Gio Ponti and Ettore Sottsass, and Italian phrases such as Bel Disegno and Linea Italiana have entered the vocabulary of furniture design.[300] Examples of classic pieces of Italian white goods and pieces of furniture include Zanussi's washing machines and fridges,[301] the "New Tone" sofas by Atrium,[301] and the post-modern bookcase by Ettore Sottsass, inspired by Bob Dylan's song "Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again".[301]

Italy is recognized as being a worldwide trendsetter and leader in design.[302] Italy today still exerts a vast influence on urban design, industrial design, interior design, and fashion design worldwide.[302] Today, Milan and Turin are the nation's leaders in architectural design and industrial design. The city of Milan hosts the FieraMilano, Europe's biggest design fair.[303] Milan also hosts major design and architecture-related events and venues, such as the Fuori Salone and the Salone del Mobile, and has been home to the designers Bruno Munari, Lucio Fontana, Enrico Castellani, and Piero Manzoni.[304]

Notable Italian fashion designers are Guccio Gucci, Salvatore Ferragamo, Giorgio Armani, Gianni Versace, Valentino, Ottavio Missoni, Nicola Trussardi, Mariuccia Mandelli, Rocco Barocco, Roberto Cavalli, Renato Balestra, Laura Biagiotti, Stefano Gabbana and Domenico Dolce.

Nobel Prizes

| Year | Winner | Branch | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1906 | Giosuè Carducci | Literature | "Not only in consideration of his deep learning and critical research, but above all as a tribute to the creative energy, freshness of style, and lyrical force which characterize his poetic masterpieces".[312] |

| 1906 | Camillo Golgi | Medicine | "In recognition of his work on the structure of the nervous system".[313] |

| 1907 | Ernesto Teodoro Moneta | Peace | "For his work in the press and in peace meetings, both public and private, for an understanding between France and Italy".[314] |

| 1909 | Guglielmo Marconi | Physics | "In recognition of his contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy".[307][315][316] |

| 1926 | Grazia Deledda | Literature | "For her idealistically inspired writings which with plastic clarity picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general."[317] |

| 1934 | Luigi Pirandello | Literature | "For his bold and ingenious revival of dramatic and scenic art."[318] |

| 1938 | Enrico Fermi | Physics | "For his demonstrations of the existence of new radioactive elements produced by neutron irradiation, and for his related discovery of nuclear reactions brought about by slow neutrons."[319] |

| 1957 | Daniel Bovet | Medicine | "For his discoveries relating to synthetic compounds that inhibit the action of certain body substances, and especially their action on the vascular system and the skeletal muscles."[320] |

| 1959 | Salvatore Quasimodo | Literature | "For his lyrical poetry, which with classical fire expresses the tragic experience of life in our own times."[321] |

| 1959 | Emilio Gino Segrè | Physics | "For his discovery of the anti-proton."[322] |

| 1963 | Giulio Natta | Chemistry | "For his discoveries in the field of the chemistry and technology of high polymers."[323] |

| 1969 | Salvatore Luria | Medicine | "For his discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses."[324] |

| 1975 | Renato Dulbecco | Medicine | "For his discoveries concerning the interaction between tumour viruses and the genetic material of the cell."[325] |

| 1975 | Eugenio Montale | Literature | "For his distinctive poetry which, with great artistic sensitivity, has interpreted human values under the sign of an outlook on life with no illusions."[326] |

| 1984 | Carlo Rubbia | Physics | "For his decisive contributions to the large project, which led to the discovery of the field particles W and Z, communicators of weak interaction."[327] |

| 1985 | Franco Modigliani | Economics | "For his pioneering analyses of saving and of financial markets"."[328] |

| 1986 | Rita Levi-Montalcini | Medicine | "For his discoveries in growth factors."[329] |

| 1997 | Dario Fo | Literature | "Who emulates the jesters of the Middle Ages in scourging authority and upholding the dignity of the downtrodden."[330] |

| 2002 | Riccardo Giacconi | Physics | "For pioneering contributions to astrophysics, which have led to the discovery of cosmic X-ray sources."[331] |

| 2007 | Mario Capecchi | Medicine | "For his discoveries of principles for introducing specific gene modifications in mice by the use of embryonic stem cells."[332] |

| 2021 | Giorgio Parisi | Physics | "For the discovery of the interplay of disorder and fluctuations in physical systems from atomic to planetary scales."[333] |

Italian surnames

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Italy |

|---|

|

| People |

| Traditions |

| Literature |

Most of Italy's surnames (cognomi), with the exception of a few areas marked by linguistic minorities, derive from Italian and arose from an individual's peculiar (physical, etc.) qualities (e.g. Rossi, Bianchi, Quattrocchi, Mancini, Grasso, etc.), occupation (Ferrari, Auditore, Sartori, Tagliabue, etc.), relation of fatherhood or lack thereof (De Pretis, Orfanelli, Esposito, Trovato, etc.), and geographic location (Padovano, Pisano, Leccese, Lucchese, etc.). Some of them also indicate a remote foreign origin (Greco, Tedesco, Moro, Albanese, etc.).

| Most common surnames[334] | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Rossi |

| 2 | Ferrari |

| 3 | Russo |

| 4 | Bianchi |

| 5 | Romano |

| 6 | Gallo |

| 7 | Costa |

| 8 | Fontana |

| 9 | Conti |

| 10 | Esposito |

| 11 | Ricci |

| 12 | Bruno |

| 13 | Rizzo |

| 14 | Moretti |

| 15 | De Luca |

| 16 | Marino |

| 17 | Greco |

| 18 | Barbieri |

| 19 | Lombardi |

| 20 | Giordano |

Italian diaspora

Italian migration outside Italy took place, in different migrating cycles, for centuries.[335] A diaspora in high numbers took place after Italy's unification in 1861 and continued through 1914 with the beginning of the First World War. This rapid outflow and migration of Italian people across the globe can be attributed to factors such as the internal economic slump that emerged alongside Italy's unification, family, and the industrial boom that occurred in the world surrounding Italy.[336][337]

Italy after its unification did not seek nationalism but sought work instead.[336] However, a unified state did not automatically constitute a sound economy. The global economic expansion, ranging from Britain's Industrial Revolution in the late 18th and through mid 19th century, to the use of slave labor in the Americas did not hit Italy until much later (with the exception of the "industrial triangle" between Milan, Genoa and Turin)[336] This lag resulted in a deficit of work available in Italy and the need to look for work elsewhere. The mass industrialization and urbanization globally resulted in higher labor mobility and the need for Italians to stay anchored to the land for economic support declined.[337]

Moreover, better opportunities for work were not the only incentive to move; family played a major role and the dispersion of Italians globally. Italians were more likely to migrate to countries where they had family established beforehand.[337] These ties are shown to be stronger in many cases than the monetary incentive for migration, taking into account a familial base and possibly an Italian migrant community, greater connections to find opportunities for work, housing etc.[337] Thus, thousands of Italian men and women left Italy and dispersed around the world and this trend only increased as the First World War approached.

Notably, it was not as if Italians had never migrated before; internal migration between North and Southern Italy before unification was common. Northern Italy caught on to industrialization sooner than Southern Italy, therefore it was considered more modern technologically, and tended to be inhabited by the bourgeoisie.[338] Alternatively, rural and agro-intensive Southern Italy was seen as economically backward and was mainly populated by lower class peasantry.[338] Given these disparities, prior to unification (and arguably after) the two sections of Italy, North and South were essentially seen by Italians and other nations as separate countries. So, migrating from one part of Italy to next could be seen as though they were indeed migrating to another country or even continent.[338]

Furthermore, large-scale migrations phenomena did not recede until the late 1920s, well into the Fascist regime, and a subsequent wave can be observed after the end of the Second World War. Another wave is currently happening due to the ongoing debt crisis.

Over 80 million people of full or part Italian descent live outside Europe, with about 50 million living in South America (mostly in Brazil, which has the largest number of Italian descendants outside Italy,[60] and Argentina, where over 62.5% of the population have at least one Italian ancestor),[7] about 23 million living in North America (United States and Canada) and 1 million in Oceania (Australia and New Zealand). Others live in other parts of Europe (primarily the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Switzerland).

A historical Italian community has also existed in Gibraltar since the 16th century. To a lesser extent, people of full or partial Italian descent are also found in Africa (most notably in the former Italian colonies of Eritrea, which has 100,000 descendants,[339][340][341] Somalia, Libya, Ethiopia, and in others countries such as South Africa, with 77,400 descendants,[5] Tunisia and Egypt), in the Middle East (in recent years the United Arab Emirates has maintained a desirable destination for Italian immigrants, with currently 10,000 Italian immigrants), and Asia (Singapore is home to a sizeable Italian community).[5]

Regarding the diaspora, there are many individuals of Italian descent who are possibly eligible for Italian citizenship by method of jus sanguinis, which is from the Latin meaning "by blood". However, just having Italian ancestry is not enough to qualify for Italian citizenship. To qualify, one must have at least one Italian-born citizen ancestor who, after emigrating from Italy to another country, had passed citizenship onto their children before they naturalized as citizens of their newly adopted country. The Italian government does not have a rule regarding on how many generations born outside of Italy can claim Italian nationality.[342]

Geographic distribution of Italian speakers

The majority of Italian nationals are native speakers of the country's official language, Italian, or a variety thereof, that is regional Italian. However, many of them also speak a regional or minority language native to Italy, the existence of which predates the national language.[48][49] Although there is disagreement on the total number, according to UNESCO, there are approximately 30 languages native to Italy, although many are often misleadingly referred to as "Italian dialects".[50][43][51][52]

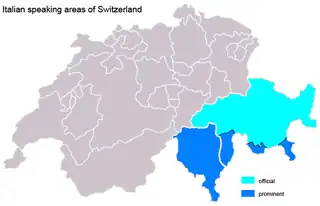

Italian is an official language of Italy and San Marino and is spoken fluently by the majority of the countries' populations. Italian is the third most spoken language in Switzerland (after German and French; see Swiss Italian), though its use there has moderately declined since the 1970s.[343] It is official both on the national level and on regional level in two cantons: Ticino and Grisons. In the latter canton, however, it is only spoken by a small minority, in the Italian Grisons.[lower-alpha 1] Ticino, which includes Lugano, the largest Italian-speaking city outside Italy, is the only canton where Italian is predominant.[344] Italian is also used in administration and official documents in Vatican City.[345]

Italian is also spoken by a minority in Monaco and France, especially in the southeastern part of the country.[346][347] Italian was the official language in Savoy and in Nice until 1860, when they were both annexed by France under the Treaty of Turin, a development that triggered the "Niçard exodus", or the emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy,[348] and the Niçard Vespers. Italian was the official language of Corsica until 1859.[349] Italian is generally understood in Corsica by the population resident therein who speak Corsican, which is an Italo-Romance idiom similar to Tuscan.[350] Italian was the official language in Monaco until 1860, when it was replaced by the French.[351] This was due to the annexation of the surrounding County of Nice to France following the Treaty of Turin (1860).[351]

It formerly had official status in Montenegro (because of the Venetian Albania), parts of Slovenia and Croatia (because of the Venetian Istria and Venetian Dalmatia), parts of Greece (because of the Venetian rule in the Ionian Islands and by the Kingdom of Italy in the Dodecanese). Italian is widely spoken in Malta, where nearly two-thirds of the population can speak it fluently.[352] Italian served as Malta's official language until 1934, when it was abolished by the British colonial administration amid strong local opposition.[353] Italian language in Slovenia is an officially recognized minority language in the country.[354] The official census, carried out in 2002, reported 2,258 ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians) in Slovenia (0.11% of the total population).[355] Italian language in Croatia is an official minority language in the country, with many schools and public announcements published in both languages.[354] The 2001 census in Croatia reported 19,636 ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians) in the country (some 0.42% of the total population).[356] Their numbers dropped dramatically after World War II following the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus, which caused the emigration of between 230,000 and 350,000 Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians.[357][358] Italian was the official language of the Republic of Ragusa from 1492 to 1807.[359]

It formerly had official status in Albania due to the annexation of the country to the Kingdom of Italy (1939–1943). Albania has a large population of non-native speakers, with over half of the population having some knowledge of the Italian language.[360] The Albanian government has pushed to make Italian a compulsory second language in schools.[361] The Italian language is well-known and studied in Albania,[362] due to its historical ties and geographical proximity to Italy and to the diffusion of Italian television in the country.[363]

Due to heavy Italian influence during the Italian colonial period, Italian is still understood by some in former colonies.[195] Although it was the primary language in Libya since colonial rule, Italian greatly declined under the rule of Muammar Gaddafi, who expelled the Italian Libyan population and made Arabic the sole official language of the country.[364] A few hundred Italian settlers returned to Libya in the 2000s.

Italian was the official language of Eritrea during Italian colonisation. Italian is today used in commerce, and it is still spoken especially among elders; besides that, Italian words are incorporated as loan words in the main language spoken in the country (Tigrinya). The capital city of Eritrea, Asmara, still has several Italian schools, established during the colonial period. In the early 19th century, Eritrea was the country with the highest number of Italians abroad, and the Italian Eritreans grew from 4,000 during World War I to nearly 100,000 at the beginning of World War II.[365] In Asmara there are two Italian schools, the Italian School of Asmara (Italian primary school with a Montessori department) and the Liceo Sperimentale "G. Marconi" (Italian international senior high school).

Italian was also introduced to Somalia through colonialism and was the sole official language of administration and education during the colonial period but fell out of use after government, educational and economic infrastructure were destroyed in the Somali Civil War.

Italian is also spoken by large immigrant and expatriate communities in the Americas and Australia.[195] Although over 17 million Americans are of Italian descent, only a little over one million people in the United States speak Italian at home.[366] Nevertheless, an Italian language media market does exist in the country.[367] In Canada, Italian is the second most spoken non-official language when varieties of Chinese are not grouped together, with 375,645 claiming Italian as their mother tongue in 2016.[368]

Italian immigrants to South America have also brought a presence of the language to that continent. According to some sources, Italian is the second most spoken language in Argentina[369] after the official language of Spanish, although its number of speakers, mainly of the older generation, is decreasing. Italian bilingual speakers can be found in the Southeast of Brazil as well as in the South, corresponding to 2.07% of the total population of the country.[370] In Venezuela, Italian is the most spoken language after Spanish and Portuguese, with around 200,000 speakers.[371] In Uruguay, people who speak Italian as their home language are 1.1% of the total population of the country.[372] In Australia, Italian is the second most spoken foreign language after Chinese, with 1.4% of the population speaking it as their home language.[373]

The main Italian-language newspapers published outside Italy are the L'Osservatore Romano (Vatican City), the L'Informazione di San Marino (San Marino), the Corriere del Ticino and the laRegione Ticino (Switzerland), the La Voce del Popolo (Croatia), the Corriere d'Italia (Germany), the L'italoeuropeo (United Kingdom), the Passaparola (Luxembourg), the America Oggi (United States), the Corriere Canadese and the Corriere Italiano (Canada), the Il punto d'incontro (Mexico), the L'Italia del Popolo (Argentina), the Fanfulla (Brazil), the Gente d'Italia (Uruguay), the La Voce d'Italia (Venezuela), the Il Globo (Australia) and the La gazzetta del Sud Africa (South Africa).[374][375][376]

Education

Italian is widely taught in many schools around the world, but rarely as the first foreign language. In the 21st century, technology also allows for the continual spread of the Italian language, as people have new ways to learn how to speak, read, and write languages at their own pace and at any given time. For example, the free website and application Duolingo has 4.94 million English speakers learning the Italian language.[377]

According to the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, every year there are more than 200,000 foreign students who study the Italian language; they are distributed among the 90 Institutes of Italian Culture that are located around the world, in the 179 Italian schools located abroad, or in the 111 Italian lecturer sections belonging to foreign schools where Italian is taught as a language of culture.[378]

As of 2022, Australia had the highest number of students learning Italian in the world. This occurred because of support by the Italian community in Australia and the Italian Government and also because of successful educational reform efforts led by local governments in Australia.[379]

Influence and derived languages

From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, thousands of Italians settled in Argentina, Uruguay, Southern Brazil and Venezuela, as well as in Canada and the United States, where they formed a physical and cultural presence.

In some cases, colonies were established where variants of regional languages of Italy were used, and some continue to use this regional language. Examples are Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, where Talian is used, and the town of Chipilo near Puebla, Mexico; each continues to use a derived form of Venetian dating back to the nineteenth century. Another example is Cocoliche, an Italian–Spanish pidgin once spoken in Argentina and especially in Buenos Aires, and Lunfardo.

Lingua franca

Starting in late medieval times in much of Europe and the Mediterranean, Latin was replaced as the primary commercial language by Italian language variants (especially Tuscan and Venetian). These variants were consolidated during the Renaissance with the strength of Italy and the rise of humanism and the arts.

During that period, Italy held artistic sway over the rest of Europe. It was the norm for all educated gentlemen to make the Grand Tour, visiting Italy to see its great historical monuments and works of art. It thus became expected to learn at least some Italian. In England, while the classical languages Latin and Greek were the first to be learned, Italian became the second most common modern language after French, a position it held until the late 18th century when it tended to be replaced by German. John Milton, for instance, wrote some of his early poetry in Italian.

Within the Catholic Church, Italian is known by a large part of the ecclesiastical hierarchy and is used in substitution for Latin in some official documents.[380]

Italian loanwords continue to be used in most languages in matters of art and music (especially classical music including opera), in the design and fashion industries, in some sports like football[381] and especially in culinary terms.

See also

Notes

References

- "Indicatori demografici Istat (Italian)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- "Sono circa 80 milioni gli oriundi italiani nel mondo" (in Italian). 4 February 2020. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- "República Italiana". itamaraty.gov.br. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "Rapporto italiani nel mondo" (PDF). Progetto culturale (in Italian). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.