Nordic walking

Nordic walking is a Finnish-origin total-body version of walking that can be done both by non-athletes as a health-promoting physical activity and by athletes as a sport. The activity is performed with specially designed walking poles similar to ski poles. Now and then this type of exercise in Finland is playfully called "dementia hiihto/dementia skiing."

History

Nordic walking (originally Finnish sauvakävely) is fitness walking with specially designed poles. While trekkers, backpackers, and skiers had been using the basic concept for decades, Nordic walking was first formally defined with the publication of "Hiihdon lajiosa" (translation: "A part of cross-country skiing training methodic") by Mauri Repo in 1979.[1] Nordic walking's concept was developed on the basis of off-season ski-training activity while using one-piece ski poles.[2]

For decades hikers and backpackers used their one-piece ski poles long before trekking and Nordic walking poles came onto the scene. Ski racers deprived of snow have always used and still do use their one-piece ski poles for ski walking and hill bounding. The first poles specially designed and marketed to fitness walkers were produced by Exerstrider of the US in 1988. Nordic Walker poles were produced and marketed by Exel in 1997. Exel coined and popularized the term 'Nordic Walking' in 1999.

Benefits

Compared to regular walking, Nordic walking (also called pole walking) involves applying force to the poles with each stride. Nordic walkers use more of their entire body (with greater intensity) and receive fitness building stimulation not present in normal walking for the chest, latissimus dorsi muscle, triceps, biceps, shoulder, abdominals, spinal and other core muscles that may result in significant increases in heart rate at a given pace.[3] Nordic walking has been estimated as producing up to a 46% increase in energy consumption, compared to walking without poles.[4][5] Several research studies have been conducted on the effects of Nordic walking. One study in particular compared regular walking to Nordic walking.[6] This study showed that Nordic walking led to more significant decreases in BMI and waist circumference compared to regular walking.[6] The Nordic walking group was the only group that experienced reductions in total body fat and increases in aerobic capacity.[6] Another research study that was done compared the effects of Nordic walking, conventional walking, and resistance-band training on overall fitness in older adults.[7] The study concluded that while all three methods are optimal for improving overall fitness, Nordic walking is the most effective.[7] Harvard Medical School has evidence that shows Nordic walking has more calorie burning characteristics than regular walking.[8]

Equipment

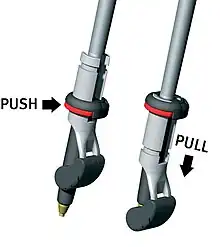

Nordic walking poles are significantly shorter than those recommended for cross-country skiing. Nordic walking poles come in one-piece, non-adjustable shaft versions, available in varying lengths, and telescoping two or three piece twist-locking versions of adjustable length. One piece poles are generally stronger and lighter, but must be matched to the user. Telescoping poles are 'one-size fits all', and are more transportable.

Nordic walking poles feature a range of grips and wrist-straps, or rarely, no wrist-strap at all. The straps eliminate the need to tightly grasp the grips. As with many trekking poles, Nordic walking poles come with removable rubber tips for use on hard surfaces and hardened metal tips for trails, the beach, snow and ice. Most poles are made from lightweight aluminium, carbon fiber, or composite materials. Special walking shoes are not required, although there are shoes being marketed as specifically designed for the sport.

Technique

The cadences of the arms, legs and body are, rhythmically speaking, similar to those used in normal, vigorous, walking. The range of arm movement regulates the length of the stride. Restricted arm movements will mean a natural restricted pelvic motion and stride length. The longer the pole thrust, the longer the stride and more powerful the swing of the pelvis and upper torso.

International Nordic Walking Federation region members

.svg.png.webp) Australia: Nordic Walking Australia (since 2006)

Australia: Nordic Walking Australia (since 2006) China: Hangzhou Nordic Gull Sports development Co., Ltd (since 2019)

China: Hangzhou Nordic Gull Sports development Co., Ltd (since 2019) Croatia: Croatian Nordic Walking Association (since 2011)

Croatia: Croatian Nordic Walking Association (since 2011) Estonia: Estonian Nordic Walking Union

Estonia: Estonian Nordic Walking Union Finland: Nordic Walking Finland ry (since 2017)

Finland: Nordic Walking Finland ry (since 2017) France: INWA France

France: INWA France Great Britain: British Nordic Walking

Great Britain: British Nordic Walking Greece: INWA Greece (since 2020)

Greece: INWA Greece (since 2020) Hong Kong: China Hong Kong Newly Emerged Sports Association Limited (since 2020)

Hong Kong: China Hong Kong Newly Emerged Sports Association Limited (since 2020) India: India Nordic Walking Organisation (since 2012)

India: India Nordic Walking Organisation (since 2012) Iran: Iranian Nordic Walking Association (since 2017)

Iran: Iranian Nordic Walking Association (since 2017) Iraq: Federation of Iraqi Sports Companies (since 2017)

Iraq: Federation of Iraqi Sports Companies (since 2017) Israel: INWA Israel Hapoel

Israel: INWA Israel Hapoel Italy: Associazione Nordic Walking Italia (since 2005)

Italy: Associazione Nordic Walking Italia (since 2005) Japan: Japan Nordic Fitness Association (JNFA) (since 2007)

Japan: Japan Nordic Fitness Association (JNFA) (since 2007) Latvia: Latvian Sports for All Association (since 2008)

Latvia: Latvian Sports for All Association (since 2008) Netherlands: Stichting Nordic Walking Nederland (since 2003)

Netherlands: Stichting Nordic Walking Nederland (since 2003) New Zealand: Nordic Walking Fitness Association of New Zealand (since 2008)

New Zealand: Nordic Walking Fitness Association of New Zealand (since 2008) Poland: PZNW Polish Nordic Walking Association (since 2021)

Poland: PZNW Polish Nordic Walking Association (since 2021) Russia: Russian Nordic Walking Association (RNWA) (since 2010)

Russia: Russian Nordic Walking Association (RNWA) (since 2010) Serbia: Nordic Walking Serbia (since 2022)

Serbia: Nordic Walking Serbia (since 2022) South Korea: INWA Korea

South Korea: INWA Korea Spain: (AENWC) INWA Spain (since 2005)

Spain: (AENWC) INWA Spain (since 2005)

See also

References

- "KOULUTUSAINEISTOA MAURI REPO : SEURAVALMENTAJAN PERUSTIEDOT HIIHDON LAJIOSA" (PDF). Tul.fi. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "The History of Nordic Walking". Inwa-nordic-walking.com. 29 May 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise VOL. 27, NO. 4 April1995:607–11

- Cooper Institute, Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sports, 2002

- Church, TS; Earnest, CP; Morss, GM (25 March 2013). "Field testing of physiological responses associated with Nordic Walking". Res Q Exerc Sport. 73 (3): 296–300. doi:10.1080/02701367.2002.10609023. PMID 12230336. S2CID 24173445.

- Muollo, Valentina; Rossi, Andrea P.; Milanese, Chiara; Masciocchi, Elena; Taylor, Miriam; Zamboni, Mauro; Rosa, Raffaela; Schena, Federico; Pellegrini, Barbara (2019). "The effects of exercise and diet program in overweight people - Nordic walking versus walking". Clinical Interventions in Aging. 14: 1555–1565. doi:10.2147/CIA.S217570. ISSN 1178-1998. PMC 6717875. PMID 31695344.

- Takeshima, Nobuo; Islam, Mohammod M.; Rogers, Michael E.; Rogers, Nicole L.; Sengoku, Naoko; Koizumi, Daisuke; Kitabayashi, Yukiko; Imai, Aiko; Naruse, Aiko (1 September 2013). "Effects of Nordic Walking Compared to Conventional Walking and Band-Based Resistance Exercise on Fitness in Older Adults". Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 12 (3): 422–430. ISSN 1303-2968. PMC 3772584. PMID 24149147.

- "Fitness trend: Nordic walking". Harvard Health. 1 November 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

External links

Media related to Nordic walking at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nordic walking at Wikimedia Commons