Helios

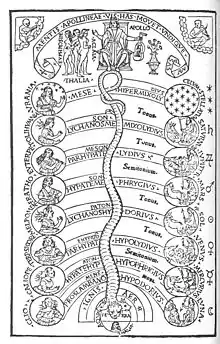

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Helios (/ˈhiːliəs, -ɒs/; Ancient Greek: Ἥλιος pronounced [hɛ̌ːlios], lit. 'Sun'; Homeric Greek: Ἠέλιος) is the titan god and personification of the Sun. His name is also Latinized as Helius, and he is often given the epithets Hyperion ("the one above") and Phaethon ("the shining").[lower-alpha 1] Helios is often depicted in art with a radiant crown and driving a horse-drawn chariot through the sky. He was a guardian of oaths and also the god of sight. Though Helios was a relatively minor deity in Classical Greece, his worship grew more prominent in late antiquity thanks to his identification with several major solar divinities of the Roman period, particularly Apollo and Sol. The Roman Emperor Julian made Helios the central divinity of his short-lived revival of traditional Roman religious practices in the 4th century AD. Often mixed with or represented as the Apollo, another god of sun, the two hold slight differences, one being a titan and personification, and the other a god over the sun and light.

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

Helios figures prominently in several works of Greek mythology, poetry, and literature, in which he is often described as the son of the Titans Hyperion and Theia and brother of the goddesses Selene (the Moon) and Eos (the Dawn). Helios' most notable role in Greek mythology is the story of his mortal son Phaethon who asked his father for a favour; Helios agreed, but then Phaethon asked for the privilege to drive his four-horse fiery chariot across the skies for a single day. Although Helios warned his son again and again against this choice, explaining to him the dangers of such a journey that no other god but him was capable to bring about, Phaethon was hard to deter, and thus Helios was forced to hand him the reins. As expected, the ride was disastrous and Zeus struck the youth with one of his lightning bolts to stop him from burning or freezing the earth beyond salvation. Other than this myth, Helios occasionally appears in myths of other characters, witnessing oaths or interacting with other gods and mortals.[3]

In the Homeric epics, his most notable role is the one he plays in the Odyssey, where Odysseus' men despite his warnings impiously kill and eat his sacred cattle the god kept at Thrinacia, his sacred island. Once informed of their misdeed, Helios in wrath asks Zeus to punish those who wronged him, and Zeus agreeing strikes their ship with a thunderbolt, killing everyone, except for Odysseus himself, the only one who had not harmed the god's cattle, and was allowed to live. After that, Helios troubles Odysseus no more in his journey.

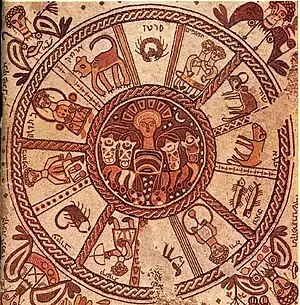

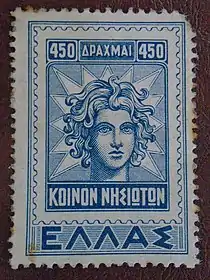

Due to his position as the sun, he was believed to be an all-seeing witness, and thus was often invoked in oaths. He also played a significant part in ancient magic and spells. In art he is usually depicted as a beardless youth in a chiton holding a whip and driving his quadriga, accompanied by various other celestial gods such as Selene, Eos, or the stars. In ancient times he was worshipped in several places of ancient Greece, though his major cult centers were the island of Rhodes, of which he was patron god, Corinth and the greater Corinthia region. The Colossus of Rhodes, a gigantic statue of the god, adorned the port of Rhodes until it was destroyed in an earthquake, thereupon it was not built again.

Name

Etymology and variants

The Greek gender view of the world was also present in their language. Ancient Greek had three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter), so when an object or a concept was personified as a deity, it inherited the gender of the relevant noun; helios is a masculine noun, so the god embodying it is also by necessity male.[4] The Greek ἥλιος (GEN ἡλίου, DAT ἡλίῳ, ACC ἥλιον, VOC ἥλιε) (from earlier ἁϝέλιος /hāwelios/) is the inherited word for the Sun from Proto-Indo-European *seh₂u-el[5] which is cognate with Latin sol, Sanskrit surya, Old English swegl, Old Norse sól, Welsh haul, Avestan hvar, etc.[6][7] The Doric and Aeolic form of the name is Ἅλιος, Hálios. In Homeric Greek his name is spelled Ἠέλιος, Ēélios, with the Doric spelling of that being Ἀέλιος, Aélios. In Cretan it was Ἀβέλιος (Abélios) or Ἀϝέλιος (Awélios).[8] The female offspring of Helios were called Heliades, the male Heliadae.

Other meanings

The author of the Suda lexicon tried to etymologically connect ἥλιος to the word ἀολλίζεσθαι, aollízesthai, "coming together" during the daytime, or perhaps from ἀλεαίνειν, aleaínein, "warming".[9] Plato in his dialogue Cratylus suggested several etymologies for the word, proposing among others a connection, via the Doric form of the word halios, to the words ἁλίζειν, halízein, meaning collecting men when he rises, or from the phrase ἀεὶ εἱλεῖν, aeí heileín, "ever turning" because he always turns the earth in his course:

Socrates: What, then, do you wish first? Shall we discuss the sun (Ἥλιος), as you mentioned it first?

Hermogenes: By all means.

Socrates: I think it would be clearer if we were to use the Doric form of the name. The Dorians call it Ἅλιος. Now ἅλιος might be derived from collecting (ἁλίζειν) men when he rises, or because he always turns (ἀεὶ εἱλεῖν) about the earth in his course, or because he variegates the products of the earth, for variegate is identical with αἰολλεῖν.

Doric Greek retained Proto-Greek long *ā as α, while Attic changed it in most cases, including in this word, to η. Cratylus and the etymologies Plato gives are contradicted by modern scholarship.[11] From helios comes the modern English prefix helio-, meaning "pertaining to the Sun", used in compounds word such as heliocentrism, aphelion, heliotropium, heliophobia (fear of the sun) and heliolatry ("sun-worship").[12]

Origins

Proto-Indo-European origin

%252C_Helios-Relief%252C_mitte.jpg.webp)

Helios most likely is Proto-Indo-European in origin. Walter Burkert wrote that "... Helios, the sun god, and Eos-Aurora, the goddess of the dawn, are of impeccable Indo-European lineage both in etymology and in their status as gods" and might have played a role in PIE poetry.[13] The imagery surrounding a chariot-driving solar deity is likely Indo-European in origin.[14][15][16] Greek solar imagery begins with the gods Helios and Eos, who are brother and sister, and who become in the day-and-night- cycle the day (hemera) and the evening (hespera), as she accompanies him in his journey across the skies. At night, he pastures his steeds and travels east in a golden boat. In them evident is the Indo-European grouping of a sun god and his sister, and the equine pair.[17]

The name Helen is thought to share the same etymology as Helios[17][18][19][20] and may express an early alternate personification of the sun among Hellenic peoples. The Proto-Indo-European sun goddess's name *Seh₂ul has been reconstructed based on several solar mythological figures, like Helios and Helen, the Germanic Sól, the Roman Sol, and others, all of which are considered derivatives of this proto-sun goddess. In PIE mythology, the Sun, a female figure, was seen as a pair with the Moon, a male figure, which in Greek mythology is recognized in the female deity Selene, usually united in marriage.[21] Martin L. West proposed the reconstruction of a PIE suffix -nā, so that Helena's name would roughly translate to "mistress of sunlight", connecting to "hḗlios" and denoting the goddess controlling the natural element.[22] Helen might have originally been considered to be a daughter of the Sun, as she hatched from an egg and was given tree worship, features associated with the PIE Sun Maiden;[23] in surviving Greek tradition however Helen is never said to be Helios' daughter, instead being the daughter of Zeus, except in one late and extremely disreputable source, Ptolemaeus Chennus.[24]

Although the Mycenaean Greek word has been reconstructed as *hāwélios, no unambiguous attestations of the word and the god for the sun have been discovered so far in Linear B tablets. It has been proposed that in the Mycenaean pantheon existed a female sun goddess, ancestor/predecessor to Helios and closely related to Helen of Troy.[25] While Helen was not a goddess in the homeric epics, she was worshipped as one in Laconia and in Rhodes, where Helios was also a major deity; those cults had not risen out of the epic myth, rather they had been so from the start.[24]

Phoenician influence

It has been suggested that the Phoenicians brought over the cult of their patron god Baal among others (such as Astarte) to Corinth, who was then continued to be worshipped under the native name/god Helios, similarly to how Astarte was worshipped as Aphrodite, and the Phoenician Melqart was adopted as the sea-god Melicertes/Palaemon, who also had a significant cult in the isthmus of Corinth.[26]

Egyptian influence

Helios' journey on a chariot during the day and travel with a boat in the ocean at night is likely a reflection of the Egyptian sun god Ra sailing across the skies in a barque and through the body of the sky goddess Nut to be reborn at dawn each morning anew; both gods were known as the (all-seeing in Helios's case) Eye of the Heaven in their respective pantheons.[27]

Description

Helios is the son of Hyperion and Theia,[28][29][30] or Euryphaessa,[31] or Aethra,[32] or Basileia,[33] the only brother of the goddesses Eos and Selene. If the order of mention of the three siblings is meant to be taken as their birth order, then out of the four authors that give him and his sisters a birth order, two make him the oldest child, one the middle, and the other the youngest.[lower-alpha 2] Helios was not among the regular and more prominent deities, rather he was a more shadowy member of the Olympian circle,[34] though in spite of him being a relatively marginal god, he was one of the most ancient ones, and one that the other gods did not want to meddle with.[35] From his lineage, Helios might thus be described as a second generation Titan, but the ancient Greeks were fairly vague on the matter.[36] Homer in the Odyssey calls him Helios Hyperion (literally "the Sun up above"), with Hyperion used in a patronymic sense to Helios. In the Odyssey, Theogony and the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Helios is once in each work called Ὑπεριονίδης (Hyperionídēs, "the son of Hyperion") and this example is followed by many later poets (like Pindar[37]), who distinguish between Helios and Hyperion; in later literature the two gods are distinctly father and son. In literature, it is not uncommon for authors to use "Hyperion's bright son" instead of his proper name when referring to the Sun.[38] He is associated with harmony and order, both in the sense of society and the literal movement of the celestial bodies; in this regard, he resembles Apollo, a god he was very often identified with.[39]

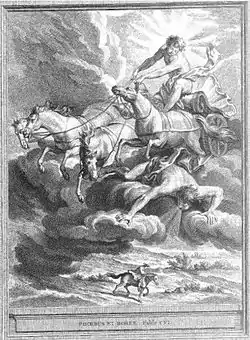

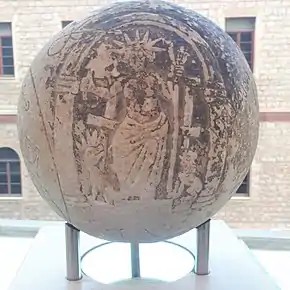

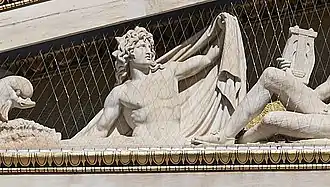

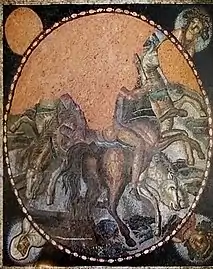

Helios is usually depicted as a handsome young man crowned with the shining aureole of the Sun who drove the chariot of the Sun across the sky each day to Earth-circling Oceanus and through the world ocean returned to the East at night. Beyond his Homeric Hymn, not many texts describe his physical appearance; Euripides describes him as χρυσωπός (khrysо̄pós) meaning "golden-eyed/faced" or "beaming like gold",[40] Mesomedes of Crete writes that he has golden hair,[41] and Apollonius Rhodius that he has light-emitting, golden eyes.[42] According to Augustan poet Ovid, he dressed in tyrian purple robes and sat on a throne of bright emeralds.[43] In ancient artefacts (such as coins, vases, or reliefs) he is presented as a beautiful youth with wavy hair,[44] a strong god in the bloom of youth, with a crown of rays upon his head.[45] His solar crown traditionally had twelve rays, symbolising the twelve months of the year.[46] He was usually represented clothed, his face somewhat full.[47] In the Homeric Hymn to Helios, Helios is said to drive the golden chariot drawn by steeds;[48] and Pindar speaks of Helios's "fire-darting steeds".[49] Still later, the horses were given fire related names: Pyrois ("The Fiery One"), Aeos ("he of the dawn"[50]), Aethon ("Blazing"), and Phlegon ("Burning"). In a Mithraic invocation, Helios's appearance is given as thus:

A god is then summoned. He is described as "a youth, fair to behold, with fiery hair, clothed in a white tunic and a scarlet cloak and wearing a fiery crown." He is named as "Helios, lord of heaven and earth, god of gods."[51]

As mentioned above, the imagery surrounding a chariot-driving solar deity is likely Indo-European in origin and is common to both early Greek and Near Eastern religions.[52][53] The earliest artistic representations of the "chariot god" come from the Parthian period (3rd century) in Persia where there is evidence of rituals being performed for the sun god by Magi, indicating an assimilation of the worship of Helios and Mithras.[14]

Helios is seen as both a personification of the Sun and the fundamental creative power behind it[54] and as a result is often worshiped as a god of life and creation. Homer described Helios as a god "who gives joy to mortals"[55] and other ancient texts give him the epithet "gracious" (ἱλαρός), given that he is the source of life and regeneration and associated with the creation of the world. The comic playwright Aristophanes in Nephelae describes Helios[56] as "the horse-guider, who fills the plain of the earth with exceeding bright beams, a mighty deity among gods and mortals."[57] One passage recorded in the Greek Magical Papyri says of Helios, "the earth flourished when you shone forth and made the plants fruitful when you laughed and brought to life the living creatures when you permitted."[14] He is said to have helped create animals out of primeval mud.[58]

Mythology

Rising and Setting

Helios was envisioned as a god driving his chariot from east to west each day, pulled by four white horses. In the ancient world people were not too troubled over how his chariot flew through the sky, as they did not envision the Earth as a spherical object, so Helios would not be travelling around a globe in an orbit; rather he crossed the sky from east to west each morning in a linear direction.[59] The chariot and his horses are mentioned by neither Homer nor Hesiod, the earliest work in which they are attested being the Homeric Hymn to Helios.[60][61][53] Although the chariot is usually said to be the work of Hephaestus,[62][63] Hyginus states that it was Helios himself who built it.[64] In one Greek vase painting, Helios appears riding across the sea in the cup of the Delphic tripod which appears to be a solar reference. His chariot is described as golden[48] or pink[65] in colour. The Horae, goddesses of the seasons, are part of his retinue and help him yoke his chariot.[66][67][68] His sister Eos is said to have not only opened the gates for Helios, but would often accompany him as well in his daily swing across the skies.[69] Every day he rose from the Ocean, the great earth-encircling river, carried by his horses:

As he rides in his chariot, he shines upon men and deathless gods, and piercingly he gazes with his eyes from his golden helmet. Bright rays beam dazzlingly from him, and his bright locks streaming from the temples of his head gracefully enclose his far-seen face: a rich, fine-spun garment glows upon his body and flutters in the wind: and stallions carry him. Then, when he has stayed his golden-yoked chariot and horses, he rests there upon the highest point of heaven, until he marvelously drives them down again through heaven to Ocean.

In Homer, he is said to go under the earth at sunset, but it is not clear whether that means he travels through Tartarus.[70] Athenaeus in his Deipnosophistae relates that, at the hour of sunset, Helios climbs into a great cup of solid gold in which he passes from the Hesperides in the farthest west to the land of the Ethiops, with whom he passes the dark hours. According to Athenaeus, Mimnermus said that in the night Helios travels eastwards with the use of a bed (also created by Hephaestus) in which he sleeps, rather than a cup,[71] and writes that "Helios gained a portion of toil for all his days", as there is no rest for either him or his horses.[72] Just like his chariot and horses, the cup is attested in neither Hesiod nor Homer, first appearing in the Titanomachy, an 8th-century BC epic poem attributed to Eumelus of Corinth.[70] Tragedian Aeschylus in his lost play Prometheus Unbound (a sequel to Prometheus Bound) describes the sunset as such:

"There [is] the sacred wave, and the coralled bed of the Erythræan Sea, and [there] the luxuriant marsh of the Ethiopians, situated near the ocean, glitters like polished brass; where daily in the soft and tepid stream, the all-seeing Sun bathes his undying self, and refreshes his weary steeds."

In the extreme east and west lived people who tended to his horses in their stalls, people for whom summer and heat were perpetual and ripeful.[44] The sun god is described as being "tireless in his journeys" as he repeats the same process day after day for an eternity.[44] Palladas sarcastically wrote that "The Sun to men is the god of light, but if he too were insolent to them in his shining, they would not desire even light."[74]

Disrupted schedule

_Flaxman_Ilias_1795%252C_Zeichnung_1793%252C_188_x_255_mm.jpg.webp)

On several instances in mythology the normal solar schedule is disrupted; he was ordered not to rise for three days during the conception of Heracles, and made the winter days longer in order to look upon Leucothoe, Athena's birth was a sight so impressive that Helios halted his steeds and stayed still in the sky for a long while,[75] as heaven and earth both trembling at the newborn goddess' sight.[76] In the Iliad Hera who supports the Greeks, makes him set earlier than usual against his will during battle,[77] and later still during the same war, after his sister Eos's son Memnon was killed, she made him downcast, causing his light to fade, so she could be able to freely steal her son's body undetected by the armies, as he consoled his sister in her grief over Memnon's death.[78] It was said that summer days are longer due to Helios often stopping his chariot mid-air to watch from above nymphs dancing during the summer,[79][80] and sometimes he is late to rise because he lingers with his consort.[81] If the other gods wish so, Helios can be hastened on his daily course when they wish it to be night.[82]

When Zeus desired to sleep with Alcmene, he made one night last threefold, hiding the light of the Sun, by ordering Helios not to rise for those three days.[83][84] Satirical author Lucian of Samosata dramatized this myth in one of his Dialogues of the Gods, where the messenger of the gods Hermes goes to Helios on Zeus' orders to tell him not to rise for three days so Zeus can spend much time with Alcmene and sire Heracles. Although Helios reluctantly agrees and wishes best luck, he complains about this decision of the king of gods, finding the reason too weak for humanity to be deprived of sunlight and stay in the dark for so long, and negatively compares Zeus to his father, claiming Cronus never abandoned his marital bed and Rhea for the love of some mortal woman.[85][lower-alpha 3] From the union of Zeus and Alcmene, Heracles was born.

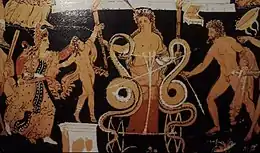

While Heracles was travelling to Erytheia to retrieve the cattle of Geryon for his tenth labour, he crossed the Libyan desert and was so frustrated at the heat that he shot an arrow at Helios, the Sun. Almost immediately, Heracles realized his mistake and apologized profusely (Pherecydes wrote that Heracles stretched his arrow at him menacingly, but Helios ordered him to stop, and Heracles in fear desisted[71]); In turn and equally courteous, Helios granted Heracles the golden cup which he used to sail across the sea every night, from the west to the east because he found Heracles' actions immensely bold. In the versions delivered by Apollodorus and Pherecydes, Heracles was only about to shoot Helios, but according to Panyassis, he did shoot and wounded the god.[87] Heracles used this golden cup to reach Erytheia, and after he had taken Geryon's cattle, returned it back to its owner.[88][89] A late sixth century or early fifth century BC lekythos depicts Heracles offering a sacrifice on one side, and Helios rising on the other, suggesting that Heracles is sacrificing to the god seeking help from him in order to reach the three-bodied Geryon.[90] On the vase, Helios is rising in his chariot between Eos and Nyx (the Night), represented as swirls of mist, while Heracles is roasting the sacrificial meat next to a lurking dog, identified as Cerberus, guiding the entrance to the Underworld; from this one can infer that the vase depicts the place in the Ocean where the earth, the sky and the sea meet, as the light of Helios is juxtaposed with the darkness of the Underworld, separated by a barrier of mist.[91]

When the brothers Thyestes and Atreus fought over which would get to rule Mycenae,[92] following the death of the previous king, Eurystheus, Atreus suggested that whoever possessed of a splendid golden ram would be declared king. Unbeknownst to Atreus, his unfaithful wife Aerope had given Thyestes the ram, and thus Thyestes became king. Zeus sent Hermes to Atreus, telling Atreus to get Thyestes to agree that should the Sun rise in the west and set in the east, the kingship would be given to Atreus.[93] Thyestes agreed, and Helios indeed rose where he usually set, and set where he usually rose, not standing the unfairness of Thyestes' actions.[94] The Mycenaeans then bowed to the man who had accomplished such an achievement and reversed the course of the Sun.[95] According to Plato, Helios at first used to rise in the west and set in the east, and only changed that after the incident of the golden ram, as did the other celestial bodies which followed suit.[96]

Solar eclipses

Solar eclipses were phaenomena of fear as well as wonder in Ancient Greece, and were seen as the Sun abandoning humanity.[97] According to a fragment of Archilochus, it is Zeus who blocks Helios and makes him disappear from the sky; "Zeus the Olympian veiled the light to make it night at midday even as sun was shining: so dread fear has overtaken men" he writes[98] and in one of his paeans, the lyric poet Pindar describes a solar eclipse as the Sun's light being hidden from the world, a bad omen of destruction and doom:[99]

Beam of the sun! What have you contrived, observant one, mother of eyes, highest star, in concealing yourself in broad daylight? Why have you made helpless men's strength and the path of wisdom, by rushing down a dark highway? Do you drive a stranger course than before? In the name of Zeus, swift driver of horses, I beg you, turn the universal omen, lady, into some painless prosperity for Thebes ... Do you bring a sign of some war or wasting of crops or a mass of snow beyond telling or ruinous strife or emptying of the sea on land or frost on the earth or a rainy summer flowing with raging water, or will you flood the land and create a new race of men from the beginning?

Plutarch in his Moralia writes that it is "through love of the sun that the moon herself makes her circuit, and has her meetings with him to receive from him all fertility".[101] Aristophanes describes a solar eclipse in his play Nephelae that was observed in Athens in 425 BC.[102]

Horses of Helios

Some lists, cited by Hyginus, of the names of horses that pulled Helios' chariot, are as follows. Scholarship acknowledges that, despite differences between the lists, the names of the horses always seem to refer to fire, flame, light and other luminous qualities.[103]

- According to Eumelus of Corinth – late 7th/ early 6th century BC: The male trace horses are Eous (by him the sky is turned) and Aethiops (as if flaming, parches the grain) and the female yoke-bearers are Bronte ("Thunder") and Sterope ("Lightning").

- According to Ovid — Roman, 1st century BC Phaethon's ride: Pyrois ("the fiery one"), Eous ("he of the dawn"), Aethon ("blazing"), and Phlegon ("burning").[104][105]

Hyginus writes that according to Homer, the horses' names are Abraxas and Therbeeo; but Homer makes no mention of horses or chariot.[104]

Alexander of Aetolia, cited in Athenaeus, related that the magical herb grew on the island Thrinacia, which was sacred to Helios, and served as a remedy against fatigue for the sun god's horses. Aeschrion of Samos informed that it was known as the "dog's-tooth" and was believed to have been sown by Cronus.[106]

Awarding of Rhodes

According to Pindar,[107] when the gods divided the earth among them, Helios was absent, and thus he got no lot of land. He complained to Zeus about it, who offered to do the division of portions again, but Helios refused the offer, for he had seen a new land emerging from the deep of the sea; a rich, productive land for humans and good for cattle too. Helios asked for this island to be given to him, and Zeus agreed to it, with Lachesis (one of the three Fates) raising her hands to confirm the oath. Alternatively in another tradition, it was Helios himself who made the island rise from the sea when he caused the water which had overflowed it to disappear.[108] He named it Rhodes, after his lover Rhode (the daughter of Poseidon and Aphrodite[109] or Amphitrite[110]), and it became the god's sacred island, where he was honoured above all other gods. With Rhode Helios sired seven sons, known as the Heliadae ("sons of the Sun"), who became the first rulers of the island, as well as one daughter, Electryone.[108] Three of their grandsons founded the cities Ialysos, Camiros and Lindos on the island, named after themselves;[107] thus Rhodes came to belong to him and his line, with the autochthonous peoples of Rhodes claiming descend from the Heliadae.[111]

Once Athena was born from Zeus' head, Helios enjoined his children and the rest of the Rhodians to immediately build an altar for the goddess quickly, in order to win her favour (and apparently he disclosed the same to the Atticans too[108]); they did as he told them, however they forgot to bring fire with them to properly do the sacrifice. Zeus, however, sent a golden cloud and rained gold on them, and Athena still graced them with unmatched skill in every art.[112] For this reason, Athena was worshipped in Rhodes with flameless sacrifices; the victim would be slain on the altar of burn offering, but the fire was not set on the altar.[113]

Phaethon

The most well known story about Helios is the one involving his son Phaethon, who asked him to drive his chariot for a single day. Although all versions agree that Phaethon convinced Helios to give him his chariot, and that he failed in his task with disastrous results, there is a great number of details that vary by version, including the identity of Phaethon's mother, the location the story takes place, the role Phaethon's sisters the Heliades play, the motivation behind Phaethon's decision to ask his father for such thing, and even the exact relation between god and mortal.

Traditionally Phaethon was Helios' son by the Oceanid nymph Clymene,[114] or alternatively Rhode[115] or the otherwise unknown Prote.[116] In one version of the story, Phaethon is Helios' grandson, rather than son, through the boy's father Clymenus. In this version, Phaethon's mother is an Oceanid nymph named Merope.[117]

In Euripides' lost play Phaethon, surviving only in twelve fragments, Phaethon is the product of an illicit liaison between his mother Clymene (who is now married to Merops, the king of Aethiopia) and Helios, though she claimed that her lawful husband was the father of her all her children.[118][119] Clymene reveals the truth to her son, and urges him to travel east to get confirmation from his father after she informs him that Helios promised to grant their child any wish when he slept with her. Although reluctant at first, Phaethon is convinced and sets on to find his birth father.[120] In a surviving fragment from the play, Helios accompanies his son in his ill-fated journey in the skies, trying to give him instructions on how to drive the chariot while he rides on a spare horse named Sirius,[121] as someone, perhaps a paedagogus informs Clymene of Phaethon's fate, who is probably accompanied by slave women:

Take, for instance, that passage in which Helios, in handing the reins to his son, says—

"Drive on, but shun the burning Libyan tract;

The hot dry air will let thine axle down:

Toward the seven Pleiades keep thy steadfast way."And then—

"This said, his son undaunted snatched the reins,

Then smote the winged coursers' sides: they bound

Forth on the void and cavernous vault of air.

His father mounts another steed, and rides

With warning voice guiding his son. 'Drive there!

Turn, turn thy car this way."

If this messenger did witness the flight himself, it is possible there was also a passage where he described Helios taking control over the bolting horses in the same manner as Lucretius described.[123] Phaethon inevitably dies; a fragment near the end of the play has Clymene order the slave girls hide Phaethon's still-smouldering body from Merops, and laments Helios' role in her son's death, saying he destroyed him and her both.[124] Near the end of the play it seems that Merops, having found out about Clymene's affair and Phaethon's true parentage, tries to kill her; her eventual fate is unclear, but it has been suggested she is saved by some deus ex machina.[125] A number of deities have been proposed for the identity of this possible deus ex machina, with Helios among them.[125]

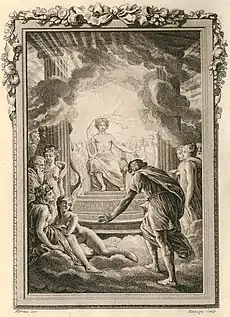

In Ovid's account, Zeus' son Epaphus mocks Phaethon's claim that he is the son of the sun god; his mother Clymene tells Phaethon to go to Helios himself, to ask for confirmation of his paternity, and the boy travels east to meet his father. Helios, living in a palace far away and attended by several other gods, warmly receives his son, and promises him on the river Styx any gift that he might ask as a proof of paternity; Phaethon asks for the privilege to drive Helios' chariot for a single day, causing his father to immediately regret his gift. Although Helios warns his son of how dangerous and disastrous this would be, and keeps begging Phaethon to rethink his wish, he is nevertheless unable to change Phaethon's mind or revoke his promise. Phaethon takes the reins in his father's horror, and drives the chariot with catastrophic results; the earth burns when he travels too low, and freezes when he takes the chariot too high. Zeus, in order to save the world, strikes Phaethon with a lightning, killing him. Helios, in his sorrow and deprived of all light out of grief, refuses to resume his job, but he returns to his task and duty at the appeal of the other gods, as well as Zeus' threats. He then takes his anger out on his four horses, whipping them in fury for causing his son's death.[126]

Nonnus of Panopolis presented a slightly different version of the myth, narrated by Hermes; according to him, Helios met and fell in love with Clymene, the daughter of the Ocean, and the two soon got married with her father's blessing; Merops does not factor at all, and their son Phaethon is born within marriage. When he grows up, fascinated with his father's job, he asks him to drive his chariot for a single day. Helios does his best to dissuade him, arguing that sons are not necessarily fit to step into their fathers' shoes, bringing up as example that none of Zeus' sons wields lightning bolts like he does. But under pressure of Phaethon and Clymene's begging both, he eventually gives in, and gives his son the reins and instructions for the road. As per all other versions of the myth, Phaethon's ride is catastrophic and ends in his death.[127]

Hyginus wrote that Phaethon secretly mounted his father's car without said father's knowledge and leave, but with the aid of his sisters the Heliades who yoked the horses, implying the existence of an early version, where Phaethon and his (full) sisters are legitimate offspring of the sun god and his wife, brought up in their father's house, rather than product(s) of an extramarital liaison.[128]

At any point, Helios recovered the reins in time, thus saving the earth and keeping it from burning to a cinder due to the flames from the chariot.[129] Another consistent detail across versions are that Phaethon's sisters the Heliades mourn him by the Eridanus and are turned into black poplar trees, who shed tears of amber. According to Quintus Smyrnaeus, it was Helios who turned them into trees, for their honour to Phaethon.[130] The part concerning the Heliades might have been a mythical device to account for the origin of amber; it is probably of no coincidence that the Greek word for amber, elektron (ἤλεκτρον), resembles elektor (ἠλέκτωρ), an epithet of Helios.[131] The poplar tree was considered sacred to Helios, due to the sun-like brilliance its shining leaves have.[132] A sacred poplar in an epigram written by Antipater of Thessalonica warns the reader not to harm her because Helios cares for her.[133] In one version of the myth, Helios conveyed his dead son to the stars, as a constellation (the Auriga).[134]

The aftermath of this episode was satirized by Lucian; in one of his dialogues, Zeus angrily berates Helios for lenting his chariot to his inexperienced son, who burned the earth with it as Helios makes excuses for himself and his child; Zeus returns the damaged chariot to its owner and threatens Helios to zap him with one of his lightning bolts should he ever do such thing again.[135]

Relating to this is a fable from Aesop, in which Helios announces his intention to get married, causing the frogs to protest intensively. When Zeus, disturbed by all that noise, asks them to explain their stance, they reply that the Sun already burns their ponds on his own just fine; if he gets married and begets even more sons, it will sure doom them.[136]

Persephone

But, Goddess, give up for good your great lamentation.

You must not nurse in vain insatiable anger.

Among the gods Aidoneus is not an unsuitable bridegroom,

Commander-of-Many and Zeus's own brother of the same stock.

As for honor, he got his third at the world's first division

and dwells with those whose rule has fallen to his lot.

Helios saw and stood witness to everything that happened underneath him where his light shone. When Hades abducted Persephone, Helios, who was characterized with the epithet Helios Panoptes ("the all-seeing Sun"), was the only one to witness it, while Hecate only heard Persephone's screams as she was snatched away. Persephone's mother Demeter, looked far and wide in search of her daughter, and at the suggestion of Hecate, came to him, and asked him to respect her as a goddess and tell her if he had seen anything. Helios, sympathizing with her grief, told her in detail that it was Hades who, with Zeus' permission, had taken an unwilling and screaming Persephone to the Underworld to be his wife and queen,[138] and that Zeus had not only permitted the marriage but also consented to the abduction.[139]

In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter he asks Demeter to sooth her pain, as Hades is not an unworthy son-in-law or bridegroom[lower-alpha 4] for her, being her own brother and king of the Underworld besides, living with those he was chosen by lot to rule over, before he yokes his winged horses and chariot and ascends in the sky as the day breaks. In Ovid's Fasti, Demeter asks the stars first about Persephone's whereabouts, and it is Helice (the constellation Ursa Major) who advises her to go ask Helios, for the night knew nothing of those events. Demeter is not slow to approach him, and Helios then tells her not to waste time, and seek out for "the queen of the third world", the bride of Zeus's brother.[141]

Helios and Hecate informing Demeter of Persephone's abduction seems to be based on a common theme found in many parts of the world where the Sun and the Moon are questioned concerning events that happen below based on their perceived ability to bear witness to everything that take place on earth, and is one of the earliest examples of Hecate's connection to the moon and Helios.[142][143]

Ares and Aphrodite

In another myth, Aphrodite was married to Hephaestus, but she cheated on him with his brother Ares, god of war. In Book Eight of the Odyssey, the blind singer Demodocus describes how the illicit lovers committed adultery, until one day Helios caught them in the act, and immediately informed Aphrodite's husband Hephaestus. Upon learning that, Hephaestus forged a net so thin it could hardly be seen, in order to ensnare them. He then announced that he was leaving for Lemnos. Upon hearing that, Ares went to Aphrodite and the two lovers coupled.[144] Once again Helios informed Hephaestus, who came into the room and trapped them in the net. He then called the other gods to witness the humiliating sight.[145]

Much later versions add a young man to the story, a warrior named Alectryon, tasked by Ares to stand guard should anyone approach. But Alectryon fell asleep, allowing Helios to discover the two lovers and inform Hephaestus. In his anger, Ares turned Alectryon into a rooster, a bird that to this day crows at dawn, to announce the arrival of the Sun.[146][147][148] According to Pausanias, the rooster is Helios' sacred animal, always crowing when he is about to rise.[149] For this, Aphrodite hated Helios and his race for all time.[150] In some versions, she cursed his daughter Pasiphaë to fall in love with the Cretan Bull as revenge against him.[151][152] Pasiphaë's daughter Phaedra's passion for her step-son Hippolytus was also said to have been inflicted on her by Aphrodite for this same reason.[150]

Leucothoe and Clytie

For Helios' tale-telling, Aphrodite would have her revenge on him. She made him fall for a mortal princess named Leucothoe, forgetting his previous lover the Oceanid Clytie for her sake. "And he that betrayed her stolen love was equally betrayed by love. What now avail, O son of Hyperion, thy beauty and brightness and radiant beams? For thou, who dost inflame all lands with thy fires, art thyself inflamed by a strange fire. Thou who shouldst behold all things, dost gaze on Leucothoe alone, and on one maiden dost thou fix those eyes which belong to the whole world. Anon too early dost thou rise in the eastern sky, and anon too late dost thou sink beneath the waves, and through thy long lingering over her dost prolong the short wintry hours. Sometimes thy beams fail utterly, thy heart's darkness passing to thy rays, and darkened thou dost terrify the hearts of men. Nor is it that the moon has come 'twixt thee and earth that thou art dark; 'tis that love of thine alone that makes thy face so wan. Thou delightest in her alone.", writes Ovid. Helios would watch her from above, even making the winter days longer so he could have more time looking at her. Taking the form of her mother Eurynome, Helios entered their palace with no problem and came into the girl's room where he dismissed her servants so he would be left alone with her, using the excuse of wanting to entrust a secret to his "daughter". There he took his real form, revealing himself to the girl.

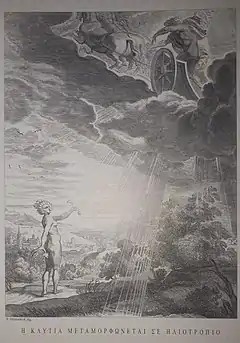

However, Clytie, still in love with him, informed Leucothoe's father Orchamus of this affair, and he buried Leucothoe alive in the earth. Helios came too late to rescue her, his grief over her death compared to the one he had over Phaethon's fiery end, and could not revive her, so instead he poured nectar into the earth, and turned the dead Leucothoe into a frankincense tree, so that she could still breathe air (after a fashion) instead of rotting beneath the soil. Clytie had hoped that this would get Helios back to her, but he wanted nothing to do with her, angered as he was about the role she played in his love's death, and went on his way. Clytie stripped herself naked, accepting no food or drink, and sat on a rock for nine days, pining after him; he never looked back at her. Eventually she turned into a purple, sun-gazing flower, the heliotrope, which follows Helios' movement in the sky, still in love with him; her form much changed, her love unchanged.[153][154] Edith Hamilton notes that this case is unique in Greek mythology, as rather than the usual, a god being in love with an unwilling maiden, it is instead the maiden who is in love with an unwilling god.[155] This myth, it has been theorized, might have been used to explain the use of frankincense aromatic resin in Helios' worship, similar to the story of Daphne for the use of laurel.[156] Leucothoe being buried alive as punishment by a male guardian, which is not too unlike Antigone's own fate, may also indicate an ancient tradition involving human sacrifice in a vegetation cult.[156] At first the stories of Leucothoe and Clytie might had been two distinct myths concerning Helios that were later combined along with a third story, that of Helios discovering Ares and Aphrodite's affair and then informing Hephaestus, into a single tale either by Ovid himself or his source.[157]

Clytie's herb has been identified with the purple heliotropium, however people from the Middle Ages onwards have supplanted it with the yellow sunflower in retellings, commentaries and artwork, even though in the story Ovid describes it as purple, or "like a violet".[158] Moreover, sunflowers are native to North America,[159] not Greece or Italy, so it is unlikely ancient writers would have been familiar with it.

Other

In Sophocles' play Ajax, Ajax the Great, minutes before committing suicide, calls upon Helios to stop his golden reins when he reaches Ajax' native land of Salamis and inform his aging father Telamon and his mother of their son's fate and death, and salutes him one last time before he kills himself.[160]

Involvement in wars

The Titanomachy

Helios sided with the other gods in several battles; during what appears to have been the Titanomachy,[lower-alpha 5] Zeus sacrificed a bull to him, Gaia, and Uranus, and in accordance they revealed to him the will of the gods in the affair, the omens indicating the victory of the gods and a defection to them of the enemy.[161] Surviving fragments from the lost poem Titanomachy, traditionally attributed to Eumelus of Corinth (8th century BC), imply scenes where Helios is the only one among the Titans to have abstained from attacking the Olympian gods,[162] and they, after the war was over, in recognition of the help he offered, gave him a place in the sky and awarded him with a chariot, drawn by two male and two female horses, to drive during the day and a vessel in which he would sail the ocean at night.[163][164]

The Gigantomachy

He also took part in the Giant wars; it was said by Pseudo-Apollodorus that during the battle of the Giants against the gods, the giant Alcyoneus stole Helios' cattle from Erytheia where the god kept them,[165] or alternatively, that it was Alcyoneus' very theft of the cattle that started the war.[166][167] Because the earth goddess Gaia, mother and ally of the Giants, learned of the prophecy that the giants would perish at the hand of a mortal, she sought to find a magical herb that would protect them and render them practically indestructible; thus Zeus ordered Helios, as well as his sisters Selene (Moon) and Eos (Dawn) not to shine, and harvested all of the plant for himself, denying Gaia the opportunity to make the Giants immortal, while Athena summoned the mortal Heracles to fight by their side.[168]

At some point during the battle of gods and giants in Phlegra, where the battle took place,[169] Helios took up an exhausted from the fight Hephaestus on his chariot (in gratitude, Hephaestus forged four ever-flowing fountains and fire-breathing bulls for Helios' son Aeëtes).[170] After the war was won and over, one of the giants, Picolous, fled the battle against Zeus; he went to Aeaea, the island where Helios' daughter, the sorceress Circe, lived. He attempted to chase Circe away from the island, only to be killed by Helios, who defended his daughter.[171][172][173] From the blood of the slain giant that dripped on the earth a new plant was sprang, the herb moly, named thus from the battle ("malos" in Ancient Greek):[174]

The plant "moly" of which Homer speaks; this plant had, it is said, grown from the blood of the giant killed in the isle of Circe; it has a white flower; the ally of Circe who killed the giant was Helios; the combat was hard (mâlos) from which the name of this plant.[175][176]

The flower had a black root, for the colour of the blood of the slain Giant, and a white flower, either for the white Sun that killed him, or for the fact that Circe grew pale of terror.[177] This is the very same plant, a plant only immortals can uproot from the ground, that Odysseus would later use on Hermes' suggestion to save his companions from Circe's magic, after she transformed them all into swines.[178] Helios is depicted in the Pergamon Altar, waging war against Giants next to his sisters Eos and Selene and his mother Theia in the southern frieze.[179][180] He is riding his four-horse chariot against a Giant, while another lays dead under the hooves of his steeds, wearing a long chiton, holding a torch on his right hand and the reins in his left.[181] His participation in the Gigantomachy (wearing a cuirass) is also depicted on a fragmentary vase by the Pronomos Painter, and perhaps in an attic column krater.[164] Additionally, a rein guide for a chariot depicts Helios and a goddess with a crescent and veil over her head, thought to be Selene, standing on a gate tower and repelling the attacks of snake-legged Giants.[182]

Gods

Despite that, he sometimes clashed with other gods; just like the Athenians had a story about how Athena and Poseidon fought over the patronage of the city of Athens, the Corinthians had a similar story about Corinth. Helios and Poseidon, representing fire versus water, clashed as to who would get to have the city. The Hecatoncheir Briareos, an elder god, was tasked to settle the dispute between the two gods; he awarded the Acrocorinth to Helios, while Poseidon was given the isthmus of Corinth.[183][184]

Aelian wrote that Nerites was the son of the sea god Nereus and the Oceanid Doris. In the version where Nerites became the lover of Poseidon, it is said that Helios turned him into a shellfish, for reasons unknown to Aelian's sources, who theorized that perhaps Helios was somehow offended. At first Aelian writes that Helios was resentful of the boy's speed, but when trying to explain why he changed his form, he suggests that perhaps Poseidon and Helios were rivals in love, and the sun god wished the youth would run among the constellations, rather than be with the sea monsters.[185][186]

In an Aesop fable, Helios and the north wind god Boreas argued about which one between them was the strongest god. They agreed that whoever was able to make a passing traveller remove his cloak would be declared the winner. Boreas was the one to try his luck first; but no matter how hard he blew, he could not remove the man's cloak, instead making him wrap his cloak around him even tighter. Helios shone bright then, and the traveller, overcome with the heat, removed his cloak, giving him the victory. The moral is that persuasion is better than force.[187] Athenaeus of Naucratis records in his Deipnosophistae that Greek author Hieronymus of Rhodes, in his Historical Notes, quoted an anecdote about playwrights Sophocles and Euripides that referenced the fable of the two gods' contest; it related how Sophocles made love to a boy outside the city's gates who then proceeded to steal Sophocles' cloak, and leave behind his own boyish one. Euripides then joked that he had had that same boy too, and it had not cost him anything. Sophocles then replied to him that "It was the Sun, and not a boy, whose heat stripped me naked; as for you, Euripides, when you were kissing someone else's wife the North Wind screwed you. You are unwise, you who sow in another's field, to accuse Eros of being a snatch-thief."[188]

Mortals

Relating to his nature as the Sun, as well as his parentage, as the son of Theia, the goddess of sight (ancient Greeks believed that eyes emitted light allowing humans to see),[189] Helios was presented as a god who could restore and also deprive of people's light as it was regarded that his light that made the faculty of sight and enabled visible things to be seen.[190] According to Pindar, the solar eye was the "forefather" of all mortal eyes, and mortals owed both sight and blindness to Helios.[191] After Orion was blinded by King Oenopion for attacking his daughter Merope, he was given a guide, Cedalion, from the god Hephaestus to guide him. Orion with Cedalion on his shoulders travelled to the east, where he met Helios. Helios then healed Orion's eyes, restoring his eyesight.[192]

Meanwhile, in Phineus's story, his blinding, as reported in Apollonius Rhodius's Argonautica, was Zeus' punishment for Phineus revealing the future to mankind.[193] For this reason he was also tormented by the Harpies, who stole or defiled whatever food he had at hand. According, however, to one of the alternative versions, it was Helios who had deprived Phineus of his sight; Phineus, when asked by Zeus if he preferred to die or lose sight as punishment for having his sons killed by their stepmother, Phineus chose the latter, saying he would rather never see the Sun than die, and consequently the offended Helios blinded him and sent the Harpies against him.[194] Pseudo-Oppian wrote that Helios' wrath was due to some obscure victory of the prophet; after Calais and Zetes slew the Harpies tormenting Phineus, Helios then turned him into a mole, a blind creature.[195] In yet another version, he blinded Phineus at the request of his son Aeëtes, who asked him to do so because Phineus had offered his assistance to Aeëtes' enemies.[196]

In another tale, in order to escape from Crete and its king Minos, the Athenian inventor Daedalus and his young son Icarus fashioned themselves wings made of birds' feathers glued together with wax and flew away.[197] According to scholia on Euripides, Icarus, being young and rashful, thought himself greater than Helios, forgetting his wings were only held together by wax. Angered, Helios hurled his blazing rays at him, melting the wax and plunging Icarus into the sea to drown. Later, it was Helios who decreed that said sea would be named after the unfortunate youth, the Icarian Sea.[198][199]

Arge was a huntress who, while hunting down a particularly fast stag, claimed that fast as the Sun as it was, she would eventually catch up to it. Helios, offended by the girl's words, changed her shape into that of a doe.[200][201]

In one rare version of Smyrna's tale, it was an angry Helios who cursed her to fall in love with her own father Cinyras because of some unspecified offence the girl committed against him; in the vast majority of other versions however, the culprit behind Smyrna's curse is the goddess of love Aphrodite.[202]

Oxen of the Sun

In his sacred island of Thrinacia, Helios kept his sacred flocks and herds of sheep and cattle. He owned seven herds of cows and many sheep as well; each flock numbered fifty beasts in it, totaling 350 cows and 350 sheep—the number of days of the year in the early Ancient Greek calendar; the seven herds correspond to the week, containing seven days.[203] The cows did not breed (thus not increasing in number) or die (thus not decreasing in number).[204] In the Homeric Hymn 4 to Hermes, after Hermes has been brought before Zeus by an angry Apollo for stealing Apollo's sacred cows, the young god excuses himself for his actions and says to his father that "I reverence Helios greatly and the other gods",[205] not unaware of Helios' special connection to cows.[206] Augeas, who in some versions is his son, safe-kept a herd of twelve bulls sacred to the god.[207] Moreover, it was said that Augeas' enormous herd of cattle, as he owned more beasts than any other rich man or king could ever acquire in life, was a gift to him by his father; he made him the greatest master of flocks, and all the cattle to thrive and prosper unceasingly, with no end.[208] Another place of their dwelling was named Erytheia, from where the Giant Alcyoneus stole them during the Gigantomachy, and it is mentioned he kept a herd of thick-fleeced sheep at Taenarum,[209] which was also a well known entrance to the Underworld, located on the tip of the Mani peninsula, between the gulfs of Messenia and Laconia.[91]

Apollonia in Illyria was another place where he kept a flock of his sheep; a man named Peithenius had been put in charge of them, but the sheep were devoured by wolves. The other Apolloniates, thinking he had been neglectful, gouged out Peithenius' eyes. Angered over the man's treatment, Helios made the earth grow barren and ceased to bear fruit; the earth grew fruitful again only after the Apolloniates had propitiated Peithenius by craft, and by two suburbs and a house he picked out, pleasing the god.[210] This story, more or less the same, albeit in a more detailed manner, is also attested by Greek historian Herodotus, who calls the man Evenius and records the story as a real historical event of the recent past, and not a mythological tale,[211] but the anecdote attests to the divine introduction of prophecy, rather than a real biographical event.[212] Herodotus adds that Evenius meant to buy new sheep to replace the ones he had lost, but was discovered, that the Apolloniates consulted the Oracle of Delphi, and were told that the god was angry at them because it was divine will for the sheep to be devoured. The Apolloniates asked Evenius what he wished in form of reparations, without mentioning the oracle, so Evenius asked for a moderate compensation.

Odyssey

During Odysseus' journey to get back home, he arrived at the island of Circe, who warned him not to touch Helios' sacred cows once he reached Thrinacia, the sun god's sacred island, where the cattle was kept, or the god would keep them from returning home:

You will now come to the Thrinacian island, and here you will see many herds of cattle and flocks of sheep belonging to the sun-god. There will be seven herds of cattle and seven flocks of sheep, with fifty heads in each flock. They do not breed, nor do they become fewer in number, and they are tended by the goddesses Phaethusa and Lampetia, who are children of the sun-god Hyperion by Neaera. Their mother when she had borne them and had done suckling them sent them to the Thrinacian island, which was a long way off, to live there and look after their father's flocks and herds. If you leave these flocks unharmed, and think of nothing but homecoming [nostos], you may yet after much hardship reach Ithaca; but if you harm them, then I forewarn you of the destruction both of your ship and of your comrades; and even though you may yourself escape, you will return late, in bad plight, after losing all your men.[213]

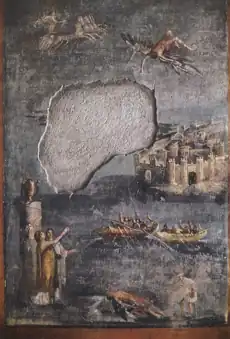

Though Odysseus warns his men, when supplies run short they impiously kill and eat some of the cattle of the Sun. The guardians of the island, Helios' daughters Phaethusa and Lampetia, tell their father about this. Helios then appeals to Zeus telling him to dispose of Odysseus' men, or he will go in the Underworld and shine among the dead instead, rejecting the crewmen's compensation of a new temple in Ithaca, and preferring a death-for-death one.[214] Zeus promises Helios that he will deal with it, and destroys the ship with his lightning bolt, killing all the men except for Odysseus.[215][216]

This episode is symbolic; the cattle of the Sun are attended to by his daughters "Bright" and "Shining", born to him by "Younger", all epithets related to the Sun.[217] By convention, Hades is the place where Helios with his light cannot reach; dying meant no longer seeing the sunlight, as being alive was to live under it, so Helios' descent to the Underworld would destabilize the balance between the dead and the living.[218] Relating to the number of cows found on the Sun's island, Eustathius wrote that each cow stood for a day in the year, thus the companions devouring the oxen of the Sun symbolizing them wasting ("eating up") their own days and life.[219] H. J. Rose disagreed with the interpretation, writing that 350 is a sacred Oriental number that reached Greece and had nothing to do with the Sun.[220] Aristotle, who also connected the number of cattle to the number to days, suggested that the reason Helios did not see the companions stealing his cattle could be explained a number of ways, such as he sees everything but not at once, or that Lampetia being the messenger is symbolic for light being messenger of sight, or that her account is similar to oath-swearing on his name.[221]

Although the proem of the Odyssey names Helios as the primary agent of retribution for the sacrilege, having "taken away the day of return" of the comrades, his role is actually limited; he resorts to threaten Zeus, and it is he who destroys the ship and the men (although in other myths, Helios is perfectly capable of exacting revenge on his own, without a middleman); by all means, Zeus should be considered the one responsible, and the attribution of their demise solely to Helios even seems biased.[222] However it could be due to that Zeus is not the one acting out of personal animosity (Helios is), rather he is asked and inclined to serve justice.[222]

Other works

Helios is featured in several of Lucian's works beyond his Dialogues of the Gods. In another work of Lucian's, Icaromenippus, Selene the Moon complains to the titular character about philosophers wanting to stir up strife and sour feelings between her and her brother with their theories about them—namely, that the moon steals her spurious light from the sun (compare the Phocylidea, where it is stated that she is not envious that his rays are much stronger than her own[223]), or calling the sun a red-hot lump.[224] Later he is seen feasting with the other gods on Olympus, and prompting Menippus to wonder how can night fall on the Heavens while he is there.[225] In A True Story, the Sun is an inhabited place, ruled by a king named Phaethon, referencing Helios's mythological son.[226] The inhabitants of the Sun are at war with those of the Moon, ruled by King Endymion (Selene's lover), over colonization of the Morning Star (Aphrodite's planet).[227][228]

Diodorus Siculus recorded an unorthodox version of the myth, in which Basileia, who had succeeded her father Uranus to his royal throne, married her brother Hyperion, and had two children, a son Helios and a daughter Selene, both admired for their beauty and their chastity. Because Basileia's other brothers envied these offspring, and feared that Hyperion would try to seize power for himself, conspired against him; they put Hyperion to the sword and drowned Helios in the river Eridanus, while Selene took her own life. After the massacre, Helios appeared in a dream to his grieving mother and assured her and their murderers would be punished, and that he and his sister would now be transformed into immortal, divine natures; what was known as Mene[229] would now be called Selene, and the "holy fire" in the heavens would bear his own name.[33][230]

It was said that due to her burning passion for the mortal Endymion, his sister Selene would often abandon the night sky to be with him;[231] during those nights that she was too preoccupied, she would give her moon chariot to Helios to drive it; although unfamiliar at first, in time he learnt to drive it like his own.[232]

Claudian wrote that in his infancy, Helios (along with Selene–their sister Eos is not mentioned with them) was nursed by his aunt the water goddess Tethys, back in the old days when his light was not as strong and his rays had not grown yet.[233]

Pausanias writes that the people of Titane in Sicyon held that Titan was a brother of Helios, the first inhabitant of Titane after whom the town was named;[234] Titan however was generally identified as Helios himself, instead of being a separate figure.[235] Pausanias rationalizes this by suggesting that Titan was probably just a man who observed the seasons of the year when the sun ripens seeds and fruits, and was said to be Helios's brother (who otherwise is characterized as an only son) for this reason.[236]

In Sophocles's play Oedipus at Colonus, Oedipus curses Creon, wishing that of all the gods may Helios, witnessing all that has happened, grant him an old age as wretched as his own.[237]

In Imagines by Philostratus, Palaestra asks him to help her with her tanning, to redden her skin with his heat.[238]

According to sixth century BC lyric poet Stesichorus, with Helios in his palace lives his mother Theia.[239]

In the myth of the dragon Python's slaying by Apollo, the slain serpent's corpse is said to have rotten in the strength of the "shining Hyperion," as the god himself promises.[240]

Aelian wrote that the wolf is a beloved animal to Helios;[241] the wolf is also Apollo's sacred animal, and the god was often known as Apollo Lyceus, "wolf Apollo".[242]

Consorts and children

The god Helios is the head of a large family, and the places that venerated him the most would also typically claim both mythological and genealogical descent from him;[189] the Cretans traced the ancestry of their king Idomeneus to Helios through his daughter Pasiphaë.[149] Though Helios had several love affairs, they were far less numerous than those of other gods, especially Zeus, since, unsurprisingly, in a warm climate it would be more likely for the rain god rather than the sun god to be seen as the fertility god.[220]

Traditionally the Oceanid nymph Perse was seen as the sun god's wife[243] by whom he had various children (depending on the version), most notably the witch Circe from the Odyssey, the king of Colchis Aeëtes, Minos' wife Pasiphaë, Perses who usurped his brother Aeëtes's kingdom, and in some versions the Corinthian king Aloeus. It is unclear what caused Perse and Helios, who is the source of all light in the world, to be the parents of such dark and mysterious children.[244] Helios distributed the land between Aloeus[245] and Aeëtes; the former received Sicyon, the latter Corinth, but Aeëtes not desiring the land, decided to make his kingdom in Colchis.[246] Ioannes Tzetzes adds Calypso, otherwise the daughter of Atlas, to the list of children Helios had by Perse, perhaps due to the similarities of the roles and personalities she and Circe display in the Odyssey as hosts of Odysseus.[247]

_MET_DP225321.jpg.webp)

Helios brought Aeëtes to Colchis, his eventual kingdom, on his chariot; in the same ride he transferred Circe to her own abode, Aeaea.[248] At some point Helios warned his son of a prophecy that stated he would suffer treachery from one of his own offspring (which Aeëtes took to mean his daughter Chalciope and her children by Phrixus).[249] Helios also bestowed several gifts on his son, such as a chariot with swift steeds,[250] a golden helmet with four plates,[251] a giant's war armor,[252] and robes and a necklace as a pledge of fatherhood.[253] When his daughter Medea betrays him and flees with Jason after stealing the golden fleece, Aeëtes called upon his father and Zeus to witness their unlawful actions against him and his people.[254]

As father of Aeëtes, Helios was also the grandfather of Medea and would play a significant role in Euripides' rendition of her fate in Corinth. When Medea offers Princess Glauce the poisoned robes and diadem, she says they were gifts to her from Helios.[255] Later, after Medea has caused the deaths of Glauce and Glauce's father King Creon, as well as her own children by Jason, Helios helps her escape Corinth and her impious husband Jason by offering her a chariot pulled by flying dragons.[256] Pseudo-Apollodorus seems to follow this version as well.[257] In Seneca's rendition of the story, a frustrated Medea criticizes the inaction of her grandfather, wondering why he has not darkened the sky at sight of such wickedness, and asks from him his fiery chariot so she can burn Corinth to the ground.[258][259] As the charioteer of the day, he is the all-seeing eye of Zeus; but as a nocturnal sojourner, he becomes associated with the occult, which is what connects him to characters like Medea as her grandfather.[260]

However he is also stated to have married other women instead like Rhodos in the Rhodian tradition[261] by whom he had seven sons, the Heliadae (Ochimus, Cercaphus, Macar, Actis, Tenages, Triopas, Candalus, and the girl Electryone), the first inhabitants of Rhodes, or even Clymene, the mother of Phaethon and the Heliades,[262] though their relationship is usually a liaison in other sources. In Nonnus' account from his epic poem the Dionysiaca, Helios and the nymph Clymene met and fell in love with each other in the mythical island of Kerne and got married, with Clymene's father Oceanus' blessing. Their wedding as attended by the Horae, Naiad nymphs who danced around, the lights of the sky such as Helios' sister Selene and Eosphorus (the planet Venus), the Hesperides, Clymene's parents Oceanus and Tethys, and others.[263] Soon Clymene fell pregnant, and their son Phaethon was born within wedlock. Her and Helios raised their child together, until the ill-fated day the boy asked his father for his chariot; Clymene too persuaded Helios to give in to Phaethon's demands.[264] A passage from Greek anthology mentions Helios visiting Clymene in her room.[265]

The mortal king of Elis Augeas was said to be Helios' son, but Pausanias states that his actual father was the mortal king Eleios; the people of Elis claimed he was the son of the Sun because of the similarity of their names, and because they wanted to glorify the king.[266]

In some rare versions, Helios is the father, rather than the brother, of his sisters Selene and Eos. A scholiast on Euripides explained that Selene was said to be his daughter since she partakes of the solar light, and changes her shape based on the position of the sun.[267]

- Anaxibia, an Indian Naiad, was lusted after by Helios according to Pseudo-Plutarch.[320]

Worship

Archaic and Classical Athens

Scholarly focus on the ancient Greek cults of Helios (as well as those of his two sisters) has generally been rather slim, partially due to how scarce both literary and archaeological sources are, and of the scattered throughout the ancient Greek world and handful cults the three siblings received, Helios was undoubtedly awarded the lion's share.[189] L.R. Farnell assumed "that sun-worship had once been prevalent and powerful among the people of the pre-Hellenic culture, but that very few of the communities of the later historic period retained it as a potent factor of the state religion".[321] The largely Attic literary sources used by scholars present ancient Greek religion with an Athenian bias, and, according to J. Burnet, "no Athenian could be expected to worship Helios or Selene, but he might think them to be gods, since Helios was the great god of Rhodes and Selene was worshiped at Elis and elsewhere".[322] James A. Notopoulos considered Burnet's distinction to be artificial: "To believe in the existence of the gods involves acknowledgment through worship, as Laws 87 D, E shows" (note, p. 264).[323] Aristophanes' Peace (406–413) contrasts the worship of Helios and Selene with that of the more essentially Greek Twelve Olympians, as the representative gods of the Achaemenid Persians (See also: Hvare-khshaeta, Mah); all the evidence shows that Helios and Selene were minor gods to the Greeks.[324]

One answer as to the reason why for that could be that the ancient Greeks envisioned their gods as very human-like, with the sun and the moon deemed too impersonal for the Greeks to relate and connect to, who would rather pray to gods like Hermes for help and protection, who could respond to concerns in a more human way; in contrast, Helios and Selene, the divine providers of heavenly light, were seen as unlikely to cease their daily routine of rising and setting in order to intervene in human affairs so they could help them.[189] Cults of luminaries were somewhat anomalous, though not, as in Helios's case, rare.[325] Helios, Eos and Selene, all Proto-Indo-European deities, were side-lined by non-PIE newcomers to the pantheon. Moreover, persisting on the sidelines seems to have been their primary function, namely to be the minor gods that the more important gods were not the same as; thus they helped keeping the Greek religion "Greek".[325]

The tension between the mainstream traditional religious veneration of Helios, which had become enriched with ethical values and poetical symbolism in Pindar, Aeschylus and Sophocles,[326] and the Ionian proto-scientific examination of the sun, a phenomenon of the study Greeks termed meteora, clashed in the trial of Anaxagoras c. 450 BC, in which Anaxagoras asserted that the Sun was in fact a gigantic red-hot ball of metal.[327] His trial was a forerunner of the culturally traumatic trial of Socrates for irreligion, in 399 BC.

Hellenistic period

Helios was not worshipped in Athens until the Hellenistic period, in post-classical times.[328] His worship might be described as a product of the Hellenistic era, influenced perhaps by the general spread of cosmic and astral beliefs during the reign of Alexander III.[329] A scholiast on Sophocles wrote that the Athenians did not offer wine as an offering to the Helios among other gods, making instead nephalia, or wineless, sober sacrifices;[330][331] Athenaeus also reported that those who sacrificed to him did not offer wine, but brought honey instead, to the altars reasoning that the god who held the cosmos in order should not succumb to drunkenness.[332] Lysimachides in the first century BC or first century AD reported of a festival Skira:

that the skiron is a large sunshade under which the priestess of Athena, the priest of Poseidon, and the priest of Helios walk as it is carried from the acropolis to a place called Skiron.[333]

During the Thargelia, a festival in honour of Apollo, the Athenians had cereal offerings for Helios and the Horae.[334] They were honoured with a procession, due to their clear connections and relevance to agriculture.[335][336] A recently published decree mentions offerings to "Sun, Seasons and Apollo",[337] showing how the three of them were associated during a festival that took place during the intense heats of the summer.[338] The procession did not neglect cereal harvest, but also introduced non-cereal as well as animal foods, all dependent for ripening on Helios and the Seasons.[338][339] Helios and the Horae were also apparently worshipped during another Athenian festival held in honor of Apollo, the Pyanopsia with a feast;[340][336] an attested procession, independent from the one recorded at the Thargelia, might have been in their honour.[337]

Side B of LSCG 21.B19 from the Piraeus Asclepium prescribe cake offerings to several gods, among them Helios and Mnemosyne,[341] two gods linked to incubation through dreams,[342] who are offered a type of honey cake called arester and a honeycomb.[343][344] The cake was put on fire during the offering.[345] A type of cake called orthostates[346][347] made of wheaten and barley flour was offered to him and the Hours.[348][349] Phthois, another flat cake[350] made with cheese, honey and wheat was also offered to him among many other gods.[349]

In many places people kept herds of red and white cattle in his honour, and white animals of several kinds, but especially white horses, were considered to be sacred to him.[45] Ovid writes that horses were sacrificed to him because no slow animal should be offered to the swift god.[351]

In Plato's Republic Helios, the Sun, is the symbolic offspring of the idea of the Good.[352]

The ancient Greeks called Sunday "day of the Sun" (ἡμέρα Ἡλίου) after him.[353] According to Philochorus, Athenian historian and Atthidographer of the 3rd century BC, the first day of each month was sacred to Helios.[354]

It was during the Roman period that Helios actually rose into an actual significant religious figure and was elevated in public cult.[355][329]

Rhodes

The island of Rhodes was an important cult center for Helios, one of the only places where he was worshipped as a major deity in ancient Greece.[356] The cult of the sun might had been brought to Rhodes by the Dorians from mainland Greece,[357] although Farnell suggested that sun worship was pre-Greek in origin.[358] Another theory is that his worship could have been imported to Rhodes from the Orient.[359] One of Pindar's most notable greatest odes is an abiding memorial of the devotion of the island of Rhodes to the cult and personality of Helios, and all evidence points that he was for the Rhodians what Olympian Zeus was for Elis or Athena for the Athenians; their local myths, especially those concerning the Heliadae, suggest that Helios in Rhodes was revered as the founder of their race and their civilization, as a great personal god, anthropomorphically imagined.[360]

The worship of Helios at Rhodes included a ritual in which a quadriga, or chariot drawn by four horses, was driven over a precipice into the sea, in reenactment to the myth of Phaethon. Athenaeus also mentions that the Rhodians celebrated a festival, the Halieia, in his honour.[361] Annual gymnastic tournaments were held in Helios' honor, and his festival that took place in summer included chariot-racing and contests of music and gymnastics;[45] according to Festus (s. v. October Equus) during the Halia each year the Rhodians would also throw quadrigas dedicated to him into the sea.[362][363][364] A team of four horses was also sacrificed to him by throwing it into the sea; horse sacrifice was offered to him in many places, but only in Rhodes in teams of four; a team of four horses was also sacrificed to Poseidon in Illyricum, and the sea god was also worshipped in Lindos under the epithet Hippios denoting perhaps a blending of the cults.[365] It was believed that if one sacrificed to the rising Sun with their day's work ahead of them, it would be proper to offer a fresh, bright white horse.[366] This festival was celebrated yearly, in the month of September,[365] and great athletes from abroad considered it worthwhile to compete; during the glorious days of the island, neighbouring independent states and the kings of Pergamos would send envoys to the festival, which was still flourishing many centuries later.[113] The Colossus of Rhodes was dedicated to him. In Xenophon of Ephesus' work of fiction, Ephesian Tale of Anthia and Habrocomes, the protagonist Anthia cuts and dedicates some of her hair to Helios during his festival at Rhodes.[367] The Rhodians called shrine of Helios, Haleion (Ancient Greek: Ἄλειον).[368] A colossal statue of the god, known as the Colossus of Rhodes and named as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was erected in his honour and adorned the port of the city of Rhodes, like the modern Statue of Liberty that stands in the harbour of New York City, to which it was comparable in both size and stature.[369]

The best of these are, first, the Colossus of Helius, of which the author of the iambic verse says, "seven times ten cubits in height, the work of Chares the Lindian"; but it now lies on the ground, having been thrown down by an earthquake and broken at the knees. In accordance with a certain oracle, the people did not raise it again.[370]

According to most contemporary descriptions, the Colossus stood approximately 70 cubits, or 33 metres (108 feet) high – approximately the height of the modern Statue of Liberty from feet to crown – making it the tallest statue in the ancient world.[371] It collapsed after an earthquake that hit Rhodes in 226 BC, and the Rhodians did not build it again, in accordance with an oracle.

In Rhodes, Helios seems to have absorbed the worship and cult of the island's local hero and mythical founder Tlepolemus.[372] In ancient Greek city foundation, the use of the archegetes in its double sense of both founder and progenitor of a political order, or a polis, can be seen with Rhodes; real prominence was transferred from the local hero Tlepolemus, onto the god, Helios, with an appropriate myth explaining his relative insignificance; thus games originally celebrated for Tlepolemus were now given to Helios, who was seen as both ancestor and founder of the polis.[373] For the Rhodian people, Tlepolemus was an archegetes and not a god, but he was offered sacrifices as if he were one; the rituals performed in his honour were of the kind commonly performed for a god.[372] A sanctuary of Helios and the nymphs stood in Loryma near Lindos.[374]

The priesthood of Helios was, at some point, appointed by lot, though in the great city a man and his two sons held the office of priesthood for the sun god in succession.[375]

Peloponnese

The Dorians also seem to have revered Helios, and to have hosted His primary cult on the mainland. The scattering of cults of the sun god in Sicyon, Argos, Hermione, Epidaurus and Laconia, and his holy livestock flocks at Taenarum, seem to suggest that the deity was considerably important in Dorian religion, compared to other parts of ancient Greece. Additionally, it may have been the Dorians who brought his worship to Rhodes, as stated above.[357]

Helios was an important god in Corinth and the greater Corinthia region. A reconstruction of Corinth's calendar from those used by its colonies reveals a summer month called "Of the [festival of the ?] Solstice", or Haliotropios in Greek (tropai = "solstice");[376] Each city in Ancient Greece had its own lunar-solar calendar organized around the annual solar cycle of solstices and equinoxes.[376] Pausanias in his Description of Greece describes how Helios and Poseidon vied over the city, with Poseidon getting the isthmus of Corinth and Helios being awarded with the Acrocorinth.[183] Helios' prominence in Corinth might go as back as Mycenaean times, and predate Poseidon's arrival[377] or it might be due to Oriental immigration; it is hard to determine.[378] At Sicyon, Helios had an altar behind Hera's sanctuary.[379] It would seem that for the Corinthians, Helios was notable enough to even have control over thunder, which is otherwise the domain of the sky god Zeus.[189]