Slavery in Brazil

Slavery in Brazil began long before the first Portuguese settlement was established in 1516, with members of one tribe enslaving captured members of another.[1] Later, colonists were heavily dependent on indigenous labor during the initial phases of settlement to maintain the subsistence economy, and natives were often captured by expeditions of bandeirantes (derived from the word for "flags", from the flag of Portugal they carried in a symbolic claiming of new lands for the country). The importation of African slaves began midway through the 16th century, but the enslavement of indigenous peoples continued well into the 17th and 18th centuries.

.jpg.webp)

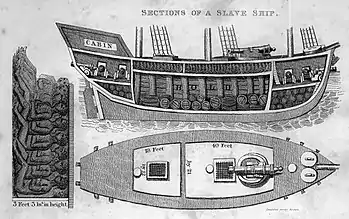

During the Atlantic slave trade era, Brazil imported more enslaved Africans than any other country in the world. Brazil's foundation was built on the exploitation and enslavement of indigenous peoples and Black Africans. Out of the 12 million Africans who were forcibly brought to the New World, approximately 5.5 million were brought to Brazil between 1540 and the 1860s. The mass enslavement of Africans played a pivotal role in the country's economy and was responsible for the production of vast amounts of wealth. The inhumane treatment and forced labor of enslaved Africans remains a significant part of Brazil's history and its ongoing struggle with systemic racism.[2][3][4] Until the early 1850s, most enslaved African people who arrived on Brazilian shores were forced to embark at West Central African ports, especially in Luanda (present-day Angola).

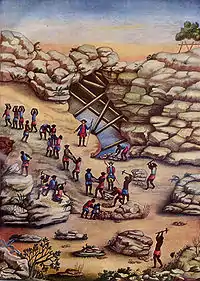

Slave labor was the driving force behind the growth of the sugar economy in Brazil, and sugar was the primary export of the colony from 1600 to 1650. Gold and diamond deposits were discovered in Brazil in 1690, which sparked an increase in the importation of enslaved African people to power this newly profitable mining. Transportation systems were developed for the mining infrastructure, and population boomed from immigrants seeking to take part in gold and diamond mining.

Demand for enslaved Africans did not wane after the decline of the mining industry in the second half of the 18th century. Cattle ranching and foodstuff production proliferated after the population growth, both of which relied heavily on slave labor. 1.7 million slaves were imported to Brazil from Africa from 1700 to 1800, and the rise of coffee in the 1830s further expanded the Atlantic slave trade.

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Brazil was the last country in the Americas to abolish slavery.

History

Slavery in medieval Portugal

The Portuguese became involved with the African slave trade first during the Reconquista ("reconquest") of the Iberian Peninsula mainly through the mediation of the Alfaqueque: the person tasked with the rescue of Portuguese captives, slaves and prisoners of war;[5][6] and then later in 1441, long before the colonization of Brazil, but now as slave traders. Slaves exported from Africa during this initial period of the Portuguese slave trade primarily came from Mauritania, and later the Upper Guinea coast. Scholars estimate that as many as 156,000 slaves were exported from 1441 to 1521 to Iberia and the Atlantic islands from the African coast. The trade made the shift from Europe to the Americas as a primary destination for slaves around 1518. Prior to this time, slaves were required to pass through Portugal to be taxed before making their way to the Americas.[7]

Indian enslavement before European arrival

Long before Europeans came to Brazil and began colonization, indigenous groups such as the Papanases, the Guaianases, the Tupinambás, and the Cadiueus enslaved captured members of other tribes. The captured lived and worked with their new communities as trophies to the tribe's martial prowess. Some enslaved would eventually escape but could never re-attain their previous status in their own tribe because of the strong social stigma against slavery and rival tribes. During their time in the new tribe, enslaved indigenes would even marry as a sign of acceptance and servitude. For the enslaved of cannibalistic tribes, execution for devouring purposes (cannibalistic ceremonies) could happen at any moment.[1][10][11]

Such reported actions of cannibalism and intertribal ransom were used to justify the enslavement of Native Americans throughout the colonial period. The Portuguese were seen as fighting a just war when enslaving indigenous populations, supposedly rescuing them from their own cruelty. This focus on pre-colonial enslavement has been criticized as it flies in the face of the reality that Portuguese enslavement of Amerindians (and later Africans) was practiced at a much larger scale than prior local enslavement practices [12]

Religious leaders at the time also pushed back against this narrative. In 1653, Padre Antônio Vieira delivered a sermon in the city of São Luís de Maranhão in which he maintained that the forced enslavement of natives was a sin, calling out his listeners for thinking that the capture of Indians was justified and "giving the pious name of rescue to a sale so forced and violent."[13]

Indigenous enslavement after European arrival

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Brazil |

|---|

|

|

|

The Portuguese first traveled to Brazil in 1500 under the expedition of Pedro Álvares Cabral, though the first Portuguese settlement was not established until 1516.[14][15][16]

Soon after the arrival of the Portuguese, it became clear a commercial colonial undertaking would be difficult on such a vast continent. Indigenous slave labor was quickly turned to for agricultural workforce needs, particularly due to the labor demands of the expanding sugar industry. Due to this pressure, slaving expeditions for Native Americans became common, despite opposition from the Jesuits who had their own ways of controlling native populations through institutions like aldeias, or villages where they concentrated Indian populations for ease of conversion. As the population of coastal Native Americans dwindled due to harsh conditions, warfare, and disease, slave traders increasingly moved further inland in bandeiras, or formal slaving expeditions.

These expeditions were composed of bandeirantes, adventurers who penetrated steadily westward in their search for Indian slaves. Bandeirantes came from a wide spectrum of backgrounds, including plantation owners, traders, and members of the military, as well as people of mixed ancestry and previously captured Indian slaves. Bandeirantes frequently targeted Jesuit missions, capturing thousands of natives from them in the early 1600s.[12] Conflict between settlers who wanted to enslave Indians and Jesuits who sought to protect them was a common pressure throughout the era, particularly as disease reduced the Indian populations. In 1661, for example, Padre Antônio Vieira's attempts to protect native populations led to an uprising and the temporary expulsion of the Jesuits in Maranhão and Pará.[12]

Beyond the capture of new slaves and recapture of runaways, bandeiras could also act as large quasi-military forces tasked with exterminating native populations who refused to be subjected to rule by the Portuguese. They also were always on the lookout for precious metals like gold and silver. As evident through an account of one of Inácio Correia Pamplona's expeditions, bandeirantes liked to think of themselves as brave civilizers who tamed the wildness of frontier by exterminating native populations and providing land for settlers. They could be compensated heavily by the crown for their efforts; Pamplona was, for example, rewarded with land grants.[13]

In 1629, Antônio Raposo Tavares led a bandeira, composed of 2,000 allied natives, 900 mamelucos, and 69 whites, to find precious metals and stones and to capture Indians for slavery. This expedition alone was responsible for the enslavement of over 60,000 indigenous people.[17][18][19][20][21]

As time went on though, it became increasingly clear that indigenous slavery alone would not meet the needs of sugar plantation labor demands. For one thing, life expectancy for Native American slaves was very low. Overwork and disease decimated native populations. Furthermore, Native Americans were familiar with the land, meaning they had the incentive and ability to escape from their slave owners. For these reasons, starting in the 1570s, African slaves became the labor force of choice on the sugar plantations. Indian slavery did continue in Brazil's frontiers until well into the 18th century, but on a smaller scale than African plantation slavery.[12]

Enslavement of Africans

In the first 250 years after the colonization of the land, roughly 70% of all immigrants to the colony were enslaved people.[22] Indigenous slaves remained much cheaper during this time than their African counterparts, though they did suffer horrendous death rates from European diseases. Although the average African slave lived to only be twenty-three years old because of terrible work conditions, this was still about four years longer than Indigenous slaves, which was a big contribution to the high price of African slaves.[23]

African slaves were also more desirable due to their experience working in sugar plantations. In a particular mill in São Vicente in the 1540s, for example, African slaves were said to have held all the most skilled positions including the crucial role of sugar master, even though they were vastly outnumbered by native slaves at the time. It is impossible to pinpoint when the first African slaves arrived in Brazil but estimates range anywhere in the 1530s. Regardless, African slavery was established at least by 1549, when the first governor of Brazil, Tome de Sousa, arrived with slaves sent from the king himself.[24]

Enslavement of other groups

Slavery was not only endured by native Indians or blacks. As the distinction between prisoners of war and slaves was blurred, the enslavement, although at a far lesser scale, of captured Europeans also took place. The Dutch were reported to have sold Portuguese, captured in Brazil, as slaves,[26] and of using African slaves in Dutch Brazil[27] There are also reports of Brazilians enslaved by Barbary pirates while crossing the ocean.[28]

In the subsequent centuries, many freed slaves and descendants of slaves became slave owners.[29] Eduardo França Paiva estimated that about one-third of slave owners were either freed slaves or descendants of slaves.[30]

Confrarias and compadrio

The Confrarias, religious brotherhoods[31][32] that included slaves, both native (Indian) and African, and non-slaves, were frequently a doorway to freedom, as was the "compadrio", co-godparenthood, a part of the kinship network.[33]

Economic changes in the 17th century

Brazil was the world's leading sugar exporter during the 17th century. From 1600 to 1650, sugar accounted for 95 percent of Brazil's exports, and slave labor was relied heavily upon to provide the workforce to maintain these export earnings. It is estimated that 560,000 Central African slaves arrived in Brazil during the 17th century in addition to the indigenous slave labor that was provided by the bandeiras.[7]

The appearance of slavery in Brazil dramatically changed with the discovery of gold and diamond deposits in the mountains of Minas Gerais in the 1690s[16] Slaves started being imported from Central Africa and the Mina coast to mining camps in enormous numbers.[7] Over the next century the population boomed from immigration and Rio de Janeiro exploded as a global export center. Urban slavery in new city centers like Rio, Recife and Salvador also heightened demand for slaves. Transportation systems for moving wealth were developed, and cattle ranching and foodstuff production expanded after the decline of the mining industries in the second half of the 18th century. Between 1700 and 1800, 1.7 million slaves were brought to Brazil from Africa[16] to make this sweeping growth possible.

The slaves who were freed and returned to Africa, the Agudás, continued to be seen as slaves by the African indigenous population. As they had left Africa as slaves, when they returned although now as free people, they were not accepted in the local society who saw them as slaves.[34] In Africa they also took part in the slave trade now as slave merchants.[35]

Resistance

There were relatively few large revolts in Brazil for much of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, most likely because the expansive interior of the country provided disincentives for slaves to flee or revolt.[16] In the years after the Haitian Revolution, ideals of liberty and freedom had spread to even Brazil. In Rio de Janeiro in 1805, "soldiers of African descent wore medallion portraits of the emperor Dessalines."[36] Jean-Jacques Dessalines was one of the African leaders of the Haitian Revolution that inspired blacks throughout the world to fight for their rights as humans to live and die free. After the defeat of the French in Haiti, demand for sugar continued to increase and without the consistent production of sugar in Haiti the world turned to Brazil as the next largest exporter [36] African slaves continued to be imported and were concentrated in the northeastern region of Bahia, a region infamous for cruel, yet prolific, sugar plantations. African slaves recently brought to Brazil were less likely to accept their condition and eventually were able to create coalitions with the purpose of overthrowing their masters. From 1807 to 1835, these groups instigated numerous slave revolts in Bahia with a violence and terror that were previously unknown.[37]

In one notable instance, enslaved people who revolted and ran away from the Engenho Santana in Bahia sent their former plantation owner a peace proposal outlining the terms under which they would return to enslavement. The enslaved people wanted peace, not war, and asked for better working conditions and more control over their time as a condition for returning.[38]

In general though, large scale, dramatic slave revolts were relatively uncommon in Brazil. Most resistance revolved around purposeful slowdowns in work or sabotage. In extreme cases, resistance also took the form of self-destruction via suicide or infanticide. The most common form of slave resistance, however, was escape.[39]

Malê revolt of 1835

The largest and most significant of Brazilian slave uprisings occurred in Salvador. It was called the Muslim uprising of 1835. It was planned by an African-born Muslim ethnic group of slaves, the Malês, as a revolt that would free all of the slaves in Bahia. While organized by the Malês, all of the African ethnic groups were represented in the participants, both Muslim and non-Muslim.[16] However, Brazilian-born slaves were conspicuously absent from the rebellion. An estimated 300 rebels were arrested, of which nearly 250 were African slaves and freedmen.[40] Brazilian-born slaves and ex-slaves represented 40% of the population of Bahia, but a total of two mulattoes and three Brazilian-born blacks were arrested during the revolt.[37] What's more, the uprising was efficiently quelled by mulatto troops by the day after its instigation.

The fact that Africans were not joined in the 1835 revolt by mulattoes was far from unusual; in fact, no Brazilian blacks had participated in the 20 previous revolts in Bahia during that time period. Masters played a large role in creating tense relations between Africans and Afro-Brazilians, for they generally favored mulattoes and native Brazilian slaves, who consequently experienced better manumission rates. Masters were aware of the importance of tension between groups to maintain the repressive status quo, as stated by Luis dos Santos Vilhema, circa 1798, "...if African slaves are treacherous, and mulattoes are even more so; and if not for the rivalry between the former and the latter, all the political power and social order would crumble before a servile revolt..." The master class was able to put mulatto troops to use controlling slaves with little backlash, thus, the freed black and mulatto population was considered as much an enemy to slaves as the white population.[37]

Not only was a unified rebellion effort against the oppressive regime of slavery prevented in Bahia by the tensions between Africans and Brazilian-born African descendants, but ethnic tensions within the African-born slave population itself prevented formation of a common slave identity.[37]

Quilombos

Escaped slaves formed maroon[41] communities which played an important role in the histories of other countries such as Suriname, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Jamaica. In Brazil the maroon settlements were called quilombos.

Quilombos were usually located near colonial population centers or towns. Apart from hostile Native American forces that prevented former slaves from penetrating deeper into Brazil's interior, the main reason for this proximity is that quilombos were usually not economically self-sufficient; relying on raids, theft, and extortion to make ends meet. In this way quilombos' presented a real threat to the colonial social order.

Colonial officials thus saw quilombo residents as criminals and quilombos themselves as threats that must be exterminated. Raids on quilombos were brutal and frequent, in some cases even employing Native Americans as slave catchers. Bandierantes also conducted raids on fugitive slave communities. In the long run, most fugitive slave communities were eventually destroyed by colonial authorities.[13]

The most famous of these communities was Quilombo dos Palmares. Here escaped slaves, army deserters, mulattos, and Native Americans flocked to participate in this alternative society. Quilombos reflected the people's will and soon the governing and social bodies of Palmares mirrored Central African political models. From 1605 to 1694 Palmares grew and attracted thousands from across Brazil. Though Palmares was eventually defeated and its inhabitants dispersed among the country, the formative period allowed for the continuation of African traditions and helped create a distinct African culture in Brazil.[42]

Recent scholarship has underscored the existence of quilombos as an important form of protest against a slave society. The word "quilombo" itself means "war-camp" and was a phrase tied to effective African military communities in Angola. This etymology has led scholar Stuart Schwartz to theorize that the use of this word among fugitive slaves in Palmares was evident of a deliberate desire among fugitive slaves to form a community with effective military might.[39]

Steps towards freedom

Brazil achieved independence from Portugal in 1822. However, the complete collapse of colonial government took place from 1821–1824.[43] José Bonifácio de Andrade e Silva is credited as the "Father of Brazilian Independence". Around 1822, Representação to the Constituent Assembly was published arguing for an end to the slave trade and for the gradual emancipation of existing slaves.[44]

Brazil's 1877–1878 Grande Seca (Great Drought) in the cotton-growing northeast led to major turmoil, starvation, poverty and internal migration. As wealthy plantation holders rushed to sell their slaves in the south, popular resistance and resentment grew, inspiring numerous emancipation societies. They succeeded in banning slavery altogether in the province of Ceará by 1884.[45]

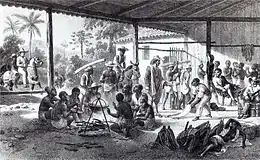

- Activists

Jean-Baptiste Debret, a French painter who was active in Brazil in the first decades of the 19th century, started out by painting portraits of members of the Brazilian Imperial Family, but soon became concerned with the slavery of both blacks and the indigenous inhabitants. During the fifteen years Debret spent in Brazil, he concentrated not only on court rituals but the everyday life of slaves as well. His paintings (one of which appears on this page) helped draw attention to the subject in both Europe and Brazil itself.

The Clapham Sect, although their religious and political influence was more active in Spanish Latin America, were a group of evangelical reformers that campaigned during much of the 19th century for the British government to use its influence and power to stop the traffic of slaves to Brazil. Besides moral qualms, the low cost of slave-produced Brazilian sugar meant that British colonies in the West Indies (which had abolished slavery) were unable to match the market prices of Brazilian sugar, and the average Briton was consuming 16 pounds (7 kg) of sugar a year by the 19th century. This combination led to diplomatic pressure from the British government for Brazil to abolish slavery, which it did by steps over three decades.[46]

The end of slavery

.tif.jpg.webp)

In 1872, the population of Brazil was 10 million, and 15% were slaves. As a result of widespread manumission (easier in Brazil than in North America), by this time approximately three quarters of the blacks and mulattoes in Brazil were free.[47] Slavery was not legally ended nationwide until 1888, when Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil, promulgated the Lei Áurea ("Golden Act"). But it was already in decline by this time (since the 1880s the country began to attract European immigrant labor instead). Brazil was the last nation in the Western world to abolish slavery, and by then it had imported an estimated 4,000,000 slaves from Africa. This was 40% of all slaves shipped to the Americas.[16]

Slave identities

In colonial Brazil, identity became a complex combination of race, skin color, and socioeconomic status because of the extensive diversity of both the slave and free population. For example, in 1872 43% of the population was free mulattoes and blacks. As shown by Family Dining, a painting created by Jean-Baptiste Debret, slaves in Brazil were often assigned new identities that reflected the status of their masters. The painting clearly depicts five slaves serving their two masters in a dining room. The slaves are depicted wearing clothing and jewelry which reflect that of their masters. For instance, the female slave on the far left side of the painting is depicted wearing a nice dress, necklaces, earrings, and a headband, demonstrating the affluence of the female slaveholder (second from the far left), who is wearing a nice dress, necklace, and headband. There are four broad categories that show the general divisions among the identities of the slave and ex-slave populations: African-born slaves, African-born ex-slaves, Brazilian-born slaves, and Brazilian-born ex-slaves.

African-born slaves

A slave's identity was stripped when sold into the slave trade, and they were assigned a new identity that was to be immediately adopted. This new identity often came in the form of a new name, consisting of a Christian or Portuguese first name randomly issued by the baptizing priest, and followed by the label of an African nation. In Brazil, these "labels" were predominantly Angola, Congo, Yoruba, Ashanti, Rebolo, Anjico, Gabon, and Mozambique.[48] Often these names served as a way for Europeans to divide Africans in a familiar manner, disregarding ethnicity or origin. Anthropologist Jack Goody stated, "Such new names served to cut the individuals off from their kinfolk, their society, from humanity itself and at the same time emphasized their servile status".[48]

A critical part of the initiation of any sort of collective identity for African-born slaves began with relationships formed on slave ships crossing the middle passage. Shipmates called each other malungos, and this relationship was considered as important and valuable as the relationship with their wives and children. Malungos were often ethnically related as well, for slaves shipped on the same boat were usually from similar geographical regions of Africa.[48]

Rosa Egipcíaca was an African-born woman, who was enslaved and taken to Rio de Janeiro. After decades of enslavement, she began to have religious visions and subsequently became widely known as a religious mystic. She founded a convent for ex-prostitutes, like herself, but was ultimately investigated by the Inquisition and punished.[49]

African-born ex-slaves

One of the most important markers of the freedom of a slave was the adoption of a last name upon being freed. These names would often be the family names of their ex-owners, either in part or in full. Since many slaves had the same or similar Christian name assigned from their baptism, it was common for a slave to be called both their Portuguese or Christian name as well as the name of their master. "Maria, for example, became known as Sr. Santana's Maria". Thus, it was mostly a matter of convenience when a slave was freed for him or her to adopt the surname of their ex-owner for assimilation into the community as a free person.[48]

Obtaining freedom was not a guarantee of escape from poverty or from many aspects of slave life. Frequently legal freedom did not come with a change in occupation for the ex-slave. However, there was increased opportunity for both sexes to become involved in wage earning. Women ex-slaves largely dominated market places selling food and goods in urban areas like Salvador, while a significant percent of African-born men freed from slavery became employed as skilled artisans, including work as sculptors, carpenters, and jewelers.[48]

Another area of income important to African-born ex-slaves was their own work as slavers upon being granted their freedom. In fact, purchase of slaves was a standard practice for ex-slaves who could afford it. This is evidence of the lack of a common identity among those born in Africa and shipped to Brazil, for it was much more common for ex-slaves to engage in the slave trade themselves than to take up any cause related to abolition or resistance to slavery.[48]

Brazilian-born slaves and ex-slaves

A Brazilian-born slave was born into slavery, meaning their identity was based on very different factors than those of the African-born who had once known legal freedom. Skin color was a significant factor in determining the status of African descendants born in Brazil: lighter-skinned slaves had both higher chances of manumission as well as better social mobility if they were granted freedom, making it important in the identity of both Brazilian-born slaves and ex-slaves.[48]

The term crioulo was primarily used in the early 19th century, and meant Brazilian-born and black. Mulatto was used to refer to lighter-skinned Brazilian-born Africans, who often were children of both African and European descent. As compared to their African-born counterparts, manumission for long-term good behavior or obedience upon the owner's death was much more likely. Thus, unpaid manumission was a much more likely path to freedom for Brazilian-born slaves than for Africans, as well as manumission in general.[50] Mulattoes also had a higher incidence of manumission, most likely because of the likelihood that they were the children of a slave and an owner.[48]

Race relations

.jpg.webp)

These color divides reinforced racial barriers between African and Brazilian slaves, and often created animosity between them. These differences were heightened after freedom was granted, for lighter skin correlated with social mobility and the greater chance an ex-slave could distance him- or herself from their former slave life. Thus, mulattoes and lighter-skinned ex-slaves had larger opportunity to improve their socioeconomic status within the confines of the colonial Brazilian social structure. As a consequence, self-segregation was common, as mulattoes preferred to separate their identity as much as possible from blacks. One way this is visible is from data on church marriages during the 19th century. Church marriage was an expensive affair, and one only the more successful ex-slaves were able to afford, and these marriages were also almost always endogamous. The fact that skin color largely dictated possible partners in marriage promoted racial distinctions as well. Interracial marriage was a rarity, and was almost always a case of a union between a white man and a mulatto woman.[48]

Gender divides

The invisibility of women in Brazilian slavery as well as in slavery in general has only been recently recognized as an important void in history. Historian Mary Helen Washington wrote, "the life of the male slave has come to be representative even though the female experience in slavery was sometimes radically different."[53] In Brazil, the sectors of slavery and wage-labor for ex-slaves were indeed distinct by gender.

Work

Labor performed by both slave and freed women was largely divided between domestic work and the market scene, which was much larger in urban cities like Salvador, Recife and Rio de Janeiro. There was a significant difference between urban and rural slavery and that had an influence on everything from work to patterns of sociability.[54] Since men usually outnumbered the women in the rural zones, many of the slaves were imported from Africa. In urban zones though, women were used highly in the domestic setting and even added to dowries for new brides. The domestic work women performed for owners was traditional, consisting of cooking, cleaning, laundry, fetching water, and childcare. Along with domestic work, the abolitionist legislation hinged upon enslaved women’s reproductive bodies (Roth). From this women were stripped of their newborns and if enslaved, were forced to practice wet nursing. Wet nursing is the mercenary act of using the breast milk produced by birthing a child and using it to feed another child. Their masters to perform wet-nursing in order to earn an income would rent out many enslaved women. There were also times where freed women would provide their breast milk to others for money. Roth explains of the 1871 Law of the Free Womb tended to increase the slave owners’ disregard for the free children of enslaved women. She goes on to say that instead of seeing these children as a potential investment, they were seen more as a nuisance and that they needed to be rid of. A new mother's milk was seen as a lucrative source of profit and as the final abolition was continuously being fought for in the 1880s, the price of the milk continued to increase and became more and more popular.[55] In the 1870s, 87–90% of slave women in Rio worked as domestic servants, and an estimated 34,000 slave and free women labored as domestics. When working as a slave in the domestic setting, you were trained as cooks, household servants, washerwomen, seamstresses, and laundresses, the more skills acquired, the higher the market value of the slave. Thus, Brazilian women in urban centers often blurred the lines that separated the work and lives of the slave and the free.[56] Many enslaved women who worked in domestics would be used as a confidant or a middle-man between elite women and the outside world. The slaves would accompany young women to visit friends and run errands for them, much like a personal assistant. These urban slaves were a capital asset to any master because by Iberian law, any child of the slave, was then a slave as well.[54]

In urban settings, African slave markets provided an additional source of income for both slave and ex-slave women, who typically monopolized sales. This trend of the marketplace being predominantly the realm of women has its origins in African customs. Wilhelm Muller, a German minister, observed in his travels to the Gold Coast, "Apart from the peasants who bring palm-wine and sugarcane to the market everyday, there are no men who stand in public markets to trade, only women."[57] The women sold tropical fruits and vegetables, cooked African dishes, candies, cakes, meat, and fish.[48]

Slave owners would buy Mina and Angolan women and girls to work as cooks, household servants, and street vendors or Quitandeiras. The women who worked as quitandeiras would acquire gold through the exchange of prepared food and aguardente (also known as sugarcane rum). Slave owners would then keep a day's wage of one pataca, and the quitandeiras were then expected to buy their own food and rum, thus causing the enslaved women and their owners to become enriched. With access to gold or to gold dust, the quitandeiras were able to purchase the freedom of their children and themselves.[58]

Prostitution was almost exclusively a trade performed by slave women, many of whom were forced into it to benefit their owners socially and financially. Prostitution was also a way that many enslaved women were able to buy their way to freedom. Municipal authorities attempted at curbing such acts by prohibiting black women, both slave and free, to be out on the street after nightfall. Much of these efforts were failed. Although many municipalities were against the exploitation of slave women in the act of prostitution, the sexual exploitation and sexual abuse that occurred under a master's roof was often ignored.[59] Slave women were also used by freed men as concubines or common-law wives and often worked for them in addition as household labor, wet nurses, cooks, and peddlers.[60] Black women during slavery in the Western hemisphere were often dehumanized. They were seen as a racial stain and had no claim to honor. Privileged virginity did not pertain to black women, which caused them to be used by both white and Latino males. Enslaved black women were more susceptible to being used by their masters, but all black women were vulnerable to sexual abuse and exploitation.[61] The religious mystic, Rosa Egipcíaca had been forced to work as a prostitute for the enslaved male workers at a gold mine in Minas Gerais.[62]

Enslaved women on plantations were often given the same work as men. Slaveholders often put slave women to work alongside men in the grueling atmosphere of the fields but were aware of ways to exploit them with regards to their gender as well. Choosing between the two was regularly a matter of expediency for the owners.[63] In both small and large estates women were heavily involved in fieldwork, and the chance to be exempted in favor of domestic work was a privilege. It was not uncommon that enslaved women would often become concubines of their masters or on a more broad spectrum, any white or mulatto man. There were many cases where these sexual liaisons were used to the slave's benefit and helped improve their day-to-day life and treatment. It also led to manumission, which is the release of slavery, or freedom. Socolow also points out in The Women of Colonial Latin America that these sexual liaisons between slave and master could also be a detriment to their future. When wives found out about the affairs between their husbands and slaves, often the slaves were immediately sold. There were times, though, when the children who were suspected to be created through the affair were sold off instead. The slaves who were successful in having a relationship with their master or with any white man usually gained wealth, manumission and in some cases, a social position.[61] Their roles in reproduction were still emphasized by owners, but often childbirth only meant that the physical demands of the field were forced to coexist with the emotional and physical pull of parenthood.[57]

Marriage in the slave world was often difficult and forbidden in some cases because of the difficulty it brought masters who intended on selling their slaves. Once slaves were married, the ability to sell the slave became that much harder, thus causing masters to often forbid marriages amongst their enslaved peoples. Since it was often forbidden. Those couples that were together but unable to marry and living in an informal consensual union were not protected under the church's law and thus could be separated at any point if the owner wanted to sell. The few female slaves who did marry usually were owned by a person of the higher social status, or those owned by religious orders and forced to wed through those orders.

Demographically, enslaved women usually stayed within their ethnic group when deciding to marry. Urban slaves were the most likely to take action legally when it came to their ability and decision to marry. They took measures to prevent owners from forcing marriage against their wills and also would sue those who attempted to prohibit them from marrying. The rural plantations were more isolated and for that their rules differed. Masters were given more opportunity to provide pressure on their female slaves to marry men chosen for them; or from the opposite side of the spectrum, owners on rural farms would forbid the marriage of slaves to another slave from a separate plantation.

Socolow explains that marriage was very rarely a legitimate marriage. The access to slaves and sexually exploiting those slaves were plentiful and thus used greatly during this time. Interracial union was discouraged, so most sexual encounters between black women or slave women and white men were done in secrecy, yet most were engaging in the act. The relations between black women and white men were often believed to be preferred because of how often white babies were nursed by slaves and black women. This also explains why black families were centered around the woman. A mother and her children were the base of the family, regardless of the ratio of men to women, which is quite opposite of the patriarchal white and Latino society.[64]

Status

The dual-sphere nature of women's work, in household domestic labor, and in the marketplace, allowed for both additional opportunities at financial resources as well as a larger social circle than their male counterparts. This gave women greater resources both as slaves and as ex-slaves, though their mobility was hindered by gender constraints. However, women often fared better in manumission possibilities. Among Brazilian-born adult ex-slaves in Salvador in the 18th century, 60% were women.[48]

There are many reasons that could explain why women were disproportionately represented in manumitted Brazilian slaves. Women who worked in the home were able to form more intimate relationships with the owner and the family, increasing their chances of unpaid manumission for reasons of "good behavior" or "obedience"[48] Additionally, male slaves were economically seen as more useful especially by landowners, making their manumission more costly to the owner and therefore for the slave himself.

Work

The work of male slaves was a much more formal affair, especially in urban settings as compared to the experience of slave women. Often, male work groups were divided by ethnicity to work as porters and transporters in gangs, transporting furniture and agricultural products by water or from ships to the marketplace. It was also the role of slave men to bring new slaves from ships to auction. Men also were used as fishermen, canoeists, oarsmen, sailors, and artisans. Up to one-fourth of slaves from 1811–1888 were employed as artisans, and many were men who worked as carpenters, painters, sculptors, and jewelers.[48]

Males also did certain kinds of domestic work in cities like Rio, Recife and Salvador, including starching, ironing, fetching water, and dumping waste.[56] On plantations outside of urban areas however, men were primarily involved in fieldwork with women. Their roles on larger estates also included working in boiling houses and tending cattle.[57]

Gender imbalances and family life

Given the physically demanding nature of plantation labor, landowners preferred male slaves over female slaves which, especially earlier in the history of slave trade, led to an imbalanced sex ratio that may have stunted family formation and lowered birth rates among slaves.[12]

Gender imbalances were also a key issue in quilmbos, leading, in some cases, to the abduction of black or mulatto women by fugitive slaves.[39] By the eighteenth century, though, birth rates among slaves became normal and marriages became more common, although the marriage rate of slaves was still lower than that of the free population. Legal marriages between slaves held some protection under Portuguese law, and it was hard for slaveowners to separate husband and wife through sale, although the same protections were not given to children.[12]

Family life among slaves was a topic of interest for observers in the nineteenth century. These observers maintained that slaves who had strong family ties were less likely to run away as they had something to lose, so they advocated for a balanced gender ratio and protection of family life among slaves in Bahia.[39]

Modern era

Contemporary slavery

In 1995, 288 farmworkers were freed from what was officially described as a contemporary forced labor situation. This number eventually rose to 583 in 2000. In 2001, however, the Brazilian government freed more than 1,400 slave laborers from many different forced labor institutions varying throughout the country. The majority of forced labor, whether coerced through debt, violence, or through another manner, is often unreported. The danger that these individuals face in their day-to-day life often make it extremely difficult to turn to authorities and report what is going on. A national survey conducted in 2000 by the Pastoral Land Commission, a Roman Catholic church group, estimated that there were more than 25,000 forced workers and slaves in Brazil.[65] In 2007, in an admission to the United Nations, the Brazilian government declared that at least 25,000–40,000 Brazilians work under work conditions "analogous to slavery." The top anti-slavery official in Brasília, Brazil's capital, estimates the number of modern enslaved at 50,000.[66]

In 2007, the Brazilian government freed more than 1,000 forced laborers from a sugar plantation.[67] In 2008, the Brazilian government freed 4,634 slaves in 133 separate criminal cases at 255 different locations. Freed slaves received a total compensation of £2.4 million (equal to $4.8 million).[68]

In March 2012, European consumer protection organizations published a study about slavery and cruelty to animals involved when producing leather shoes. A Danish organization was contracted to visit farms, slaughterhouses and tanneries in Brazil and India. The conditions of humans found were catastrophic, as well the treatment of the animals was found cruel. None of the 16 companies surveyed were able to track the used products down to the final producers. Timberland did not participate, but was found the winner as it showed at least some signs of transparency on its website.[69][70]

In 2013, the U.S. Department of Labor's Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor in Brazil reported that the children that engaged in child labor were either in agriculture or domestic work."[71]

In 2014, the Bureau of International Labor Affairs issued a List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor where Brazil was classified as one of the 74 countries still involved in child labor and forced labor practices.[72]

A 2017 report by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy suggested "thousands of workers in Brazil’s meat and poultry sectors were victims of forced labor and inhumane work conditions."[73] As a result, the South African Poultry Association (SAPA) called for an investigation on grounds of unfair competition.[73]

Carnaval and Ilê Aiyê

A yearly celebration that allows insight into race relations, Carnival is a weeklong festival celebrated all around the world. In Brazil it is associated with numerous facets of Brazilian culture: soccer, samba, music, performances, and costumes. Schools are on holiday, workers have the week off, and a general sense of jubilee fills the streets, where musicians parade around to huge crowds of cheering fans.[74]

It was during Brazil's military dictatorship, defined by many as Brazil's darkest period, when a group called Ilê Aiyê came together to protest black exclusion within the majority black state of Bahia. There had been a series of protests at the beginning of the 1970s that raised awareness for back unification but they were met with severe suppression. Prior to 1974, Afro-Bahians would leave their houses with only religious figurines to celebrate Carnival. Though under increased scrutiny attributed to the military dictatorship, Ilê Aiyê succeeded in created a black only bloco (Carnaval parade group) that manifested the ideals of the Brazilian Black Movement.[75] Their purpose was to unite the Afro-Brazilians affected by the oppressive government and politically organize so that there could be lasting change among their community.

Ilê Aiyê's numbers have since grown into the thousands. Though the media has called it ‘racist’, to a large degree the black-only bloco has become one of the most interesting aspects of Salvador's Carnaval and is continuously accepted as a way of life. Combined with the influence of Olodum[76] in Salvador, musical protest and representation as a product of slavery and black consciousness has slowly grown into a more powerful force. Musical representation of problems and issues have long been part of Brazil's history, and Ilê Aiyê and Olodum both produce creative ways to remain relevant and popular.

Legacy of slavery

Slavery as an institution in Brazil was unrivaled in all of the Americas. The sheer number of African slaves brought to Brazil and moved around South America greatly influenced the entirety of the Americas. Indigenous groups, Portuguese colonists, and African slaves all contributed to the melting pot that has created Brazil. The mixture of African religions that survived throughout slavery and Catholicism, Candomblé, has created some of the most interesting and diverse cultural aspects. In Bahia, statues of African gods called Orishas pay homage to the unique African presence in the nation's largest Afro-Brazilian state.[77] Not only are these Orishas direct links to their past ancestry, but also reminders to the cultures the Brazilian people come from. Candomblé and the Orishas serve as an ever-present reminder that African slaves were brought to Brazil. Though their lives were different in Brazil, their culture has been preserved at least to some degree.

Since the 1990s, despite the increasing public attention given to slavery through national and international initiatives like UNESCO's Slave Route Project, Brazil has mounted very few initiatives commemorating and memorializing slavery and the Atlantic slave trade. However, in the last decade Brazil has begun engaging in several initiatives underscoring its slave past and the importance of African heritage. Gradually, all over the country statues celebrating Zumbi, the leader of Palmares, Brazilian long-lasting quilombo (runaway slave community) were unveiled. Capital cities like Rio de Janeiro and even Porto Alegre created permanent markers commemorating heritage sites of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade. Among the most recent and probably the most famous initiatives of this kind is the Valong Wharf slave memorial in Rio de Janeiro (the site where almost one million enslaved Africans disembarked).[78]

Slavery and systematic inequality and disadvantage still exist within Brazil. Though much progress has been made since abolition, unequal representation in all levels of society perpetuates ongoing racial prejudice. Most obvious are the stark contrasts between white and black Brazilians in media, government, and private business. Brazil continues to grow and succeed economically, yet its poorest regions and neighborhood slums (favelas), occupied by majority Afro-Brazilians, are shunned and forgotten.[79] Large developments within cities displace poor Afro-Brazilians and the government relocates them conveniently to the periphery of the city. It has been argued that most Afro-Brazilians live as second-class citizens, working in service industries that perpetuate their relative poverty while their white counterparts are afforded opportunities through education and work because of their skin color. Advocacy for equal rights in Brazil is hard to understand because of how mixed Brazil's population is. However, there is no doubt that the number of visible Afro-Brazilian leaders in business, politics and media is disproportionate to their white counterparts.[70]

In 2012, Brazil passed an affirmative action law in an attempt to directly fight the legacy of slavery.[80] Through it Brazilian policy makers have forced state universities to have a certain quota of Afro-Brazilians. The percentage of Afro-Brazilians to be admitted, as high as 30% in some states, causes great social discontent that some argue furthers racial tensions.[81] It is argued that these high quotas are needed because of the unequal opportunities available to Afro-Brazilians.[79] In 2012 Brazil's Supreme Court unanimously held the law to be constitutional.

See also

References

- SOUSA, Gabriel Soars. Tratado Descritivo do Brasil em 1587

- "Racialized Frontiers: Slaves and Settlers in Modernizing Brazil". Brazil LAB. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- "Assessing the Slave Trade: Estimates". The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

- "VERGONHA AINDA MAIOR: Novas informações disponíveis em um enorme banco de dados mostram que a escravidão no Brasil foi muito pior do que se sabia antes (". Veja (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Leon), Alfonso X. (King of Castile and (1 January 2001). Las Siete Partidas, Volume 2: Medieval Government: The World of Kings and Warriors (Partida II). University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812217391. Retrieved 16 February 2017 – via Google Books.

- Monumenta Henricina Volume VIII – p. 78.

- Sweet, James H. Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship, and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441–1770. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2003. Print.

- Levine, Robert M.; Crocitti, John J.; Kirk, Robin; Starn, Orin (1999). The Brazil Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. p. 121. ISBN 0822322900. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- "Recife—A City Made by Sugar". Awake!. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- Índios do Brasil, p. 111, at Google Books

- Mattoso, Katia M.; Schwartz, Stuart B. (1986). To Be a Slave in Brazil: 1550–1888. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univ. Press. ISBN 0-8135-1154-2.

- Burkholder, Mark A., 1943- (2019). Colonial Latin America. Johnson, Lyman L. (Tenth ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-19-064240-2. OCLC 1015274908.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Colonial Latin America : a documentary history. Mills, Kenneth, 1964-, Taylor, William B., Lauderdale Graham, Sandra, 1943-. Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources. 2002. ISBN 0-8420-2996-6. OCLC 49649906.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Um pouco de história" (in Portuguese). IBRAC. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Biografia de Cristóvão Jacques" (in Portuguese). Ebiografia.com. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Bergad, Laird W. 2007. The Comparative Histories of Slavery in Brazil, Cuba, and the United States. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- "bandeira - Brazilian history". Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- "bandeira - Brazilian history". Archived from the original on 28 November 2006. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- "History of Brazil - the Bandeirantes". Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- António Rapôso Tavares Archived 2012-09-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Colonial Brazil: Portuguese, Tupi, etc Archived 2009-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- De Ferranti, David M. (2004). "Historical Roots of Inequality in Latin America" (PDF). Inequality in Latin America: Breaking With History?. World Bank Publications. pp. 109–122.

- Skidmore, Thomas E. (1999). Brazil: Five Centuries of Change. New York: Oxford UP. ISBN 0-19-505809-7.

- Metcalf, Alida C., 1954- (2005). Go-betweens and the colonization of Brazil, 1500-1600 (1st ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-79622-6. OCLC 605091664.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Entrevista com Laurentino Gomes: um mergulho na origem da exclusão social" (in Portuguese). Folha de Pernambuco. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Blakely, Allison (22 January 2001). Blacks in the Dutch World: The Evolution of Racial Imagery in a Modern Society. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253214335. Retrieved 16 February 2017 – via Google Books.

- A Escravidão no Brasil Holandês Archived 2014-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- "Longe de casa - Revista de História". Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- O 'bruxo africano' de Salvador Archived 2014-01-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "Mitos e equívocos sobre escravidão no Brasil". Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- SENHORAS DO CAJADO:UM ESTUDO SOBRE A IRMANDADE DA BOA MORTE DE SÃO GONÇALO DOS CAMPOS

- Donatários, Colonos, Índios e Jesuítas Archived 2012-06-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Os compadres e as comadres de escravos:um balanço da produção historiográfica brasileira

- Guran, Milton (October 2000). "Agudás - de africanos no Brasil a 'brasileiros' na África". História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos. 7 (2): 415–424. doi:10.1590/S0104-59702000000300009.

- The Afro-Brazilian legacy in the bight Benin Archived 2014-01-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Dubois, Laurent. Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004.

- Reis, João José. 1993. Slave Rebellion in Brazil: The Muslim Uprising of 1835 in Bahia. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Schwartz, Stuart B. (1977-01-01). "Resistance and Accommodation in Eighteenth-Century Brazil: The Slaves' View of Slavery". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 57 (1): 69–81. doi:10.2307/2513543. JSTOR 2513543.

- Schwartz, Stuart (2005). "Rethinking Palmares: Slave Resistance in Colonial Brazil". Oxford African American Studies Center. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.43121. ISBN 9780195301731. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- Falola, Toyin, and Matt D. Childs. The Yoruba Diaspora in the Atlantic World. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2004. Print.

- A Experiência histórica dos quilombos nas Américas e no Brasil Archived 2009-05-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Anderson, Robert Nelson (October 1996). "The Quilombo of Palmares: A New Overview of a Maroon State in Seventeenth-Century Brazil". Journal of Latin American Studies. 28 (3): 545–566. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00023889. S2CID 145748163.

- Schwartz, Stuart B. (February 1977). "Resistance and Accommodation in Brazil". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 57: 70. JSTOR 2513543.

- Nishida, Mieko (August 1993). "Manumission and Ethnicity in Urban Slavery". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 73: 315. JSTOR 2517695.

- Davis, Mike (2001). Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World. Verso. pp. 88–90. ISBN 1-85984-739-0.

- "Struggling over sugar", St. Petersburg Times.

- Ferguson, p. 131.

- Nishida, Mieko. Slavery and Identity: Ethnicity, Gender, and Race in Salvador, Brazil, 1808–1888. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2003. Print.

- "Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade". enslaved.org. Retrieved 2021-08-21.

- Moore, Brain L., B.W. Higman, Carl Campbell, and Patrick Bryan. Slavery, Freedom and Gender the Dynamics of Caribbean Society. Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies, 2003. Print.

- Barretto Briso, Caio (16 November 2014). "Um barão negro, seu palácio e seus 200 escravos". O Globo. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Lopes, Marcus (15 July 2018). "A história esquecida do 1º barão negro do Brasil Império, senhor de mil escravos". BBC. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Campbell, Gwyn, Suzanne Miers, and Joseph Calder. Miller. Women and Slavery: The Modern Atlantic. Athens: Ohio UP, 2007. Print.

- Socolow, S. M. (2015). The women of COLONIAL Latin America. In The women of colonial Latin America (pp. 191). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Roth, C. (2017, December 20). Black nurse, White Milk: Wet nursing and slavery in Brazil. Retrieved May 07, 2021, from https://nursingclio.org/2017/12/20/black-nurse-white-milk-wet-nursing-and-slavery-in-brazil/

- Lauderdale Graham, Sandra. House and Street: The Domestic World of Servants and Masters in Nineteenth-Century Rio de Janeiro. New York: Cambridge UP, 1988. Print.

- Morgan, Jennifer L. Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2004. Print.

- Finkelman, Paul & Miller, Joseph C. Brazil: An Overview. Macmillan Reference USA, 1998. Web.

- Socolow, S. M. (2015). The women of COLONIAL Latin America. In The women of colonial Latin America (pp. 193). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Karasch, Mary C. Slave Life in Rio de Janeiro 1808–1850. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1987. Print.

- Socolow, S. M. (2015). The women of COLONIAL Latin America. In The women of colonial Latin America (pp. 188-199). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Gardner, Jane; Wiedemann, Thomas (2013-11-12). Representing the Body of the Slave. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-79171-3.

- Davis, Angela Y. Women, Race & Class. New York: Vintage, 1983. Print.

- Socolow, S. M. (2015). The women of COLONIAL Latin America. In The women of colonial Latin America (pp. 196-199). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Larry Rohter, Brazil's Prized Exports Rely on Slaves and Scorched Land, The New York Times, March 25, 2002.

- Hall, Kevin G., "Slavery exists out of sight in Brazil", Knight Ridder Newspapers, 2004-09-05.

- "'Slave' labourers freed in Brazil", BBC News.

- Tom Phillips (January 3, 2009). "Brazilian task force frees more than 4,500 slaves after record number of raids on remote farms". The Guardian. London.

- In Lederschuhen steckt Sklavenarbeit, help.orf.at, 24. March 2012.

- Hall, Kevin G. "Modern Day Slavery in Brazil." Tropical Rainforest Conservation – Mongabay.com. September 5, 2004. Accessed September 11, 2014. http://www.mongabay.com/external/slavery_in_brazil.htm.

- "Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor - Brazil". 30 September 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- "List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor". Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Mendes, Karla (December 11, 2017). "South Africa poultry group calls for probe of forced labor in Brazil". Reuters. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- "Salvador, Bahia World's Greatest Street Carnaval." Carnaval.com. Accessed November 4, 2014. http://carnaval.com/cityguides/brazil/salvador/salvcarn.htm.

- Roelofse-Campbell. "The Fight against Racism in Brazil: (The Black Movement) – Assata Shakur Speaks – Hands Off Assata – Let's Get Free – Revolutionary – Pan-Africanism – Black On Purpose – Liberation – Forum." Assata Shakur Speaks! Accessed November 4, 2014. http://www.assatashakur.org/forum/afrikan-world-news/8338-fight-against-racism-brazil-black-movement.html.

- Hamilton, Russell G. (March 2007). "Gabriela Meets Olodum: Paradoxes of Hybridity, Racial Identity, and Black Consciousness in Contemporary Brazil". Research in African Literatures. 38 (1): 181–193. doi:10.1353/ral.2007.0007.

- Shirey, Heather (December 2009). "Transforming the Orixás: Candomblé in Sacred and Secular Spaces in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil". African Arts. 42 (4): 62–79. doi:10.1162/afar.2009.42.4.62. S2CID 57558875.

- African Heritage and Memories of Slavery in Brazil and the South Atlantic World

- Reiter, Bernd (March 2008). "Education reform, race, and politics in Bahia, Brazil". Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação. 16 (58): 125–148. doi:10.1590/S0104-40362008000100009.

- Smith, Erica (22 October 2010). "Affirmative Action in Brazil". Americas Quarterly.

- Hernandez, Tanya K (19 October 2006). "Bringing Clarity to Race Relations in Brazil". Diverse Issues in Higher Education. 23 (18): 85.

- Burkholder, Mark A.; Johnson, Lyman L. (2019). Colonial Latin America: Tenth Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Metcalf, Alida C. (2005). Go-Betweens and the Colonization of Brazil: 1500-1600. University of Texas Press. pp. 157–193.

Further reading

- Alonso, Angela (2021). The Last Abolition: The Brazilian Antislavery Movement, 1868–1888. Afro-Latin America. Cambridge University Press.

- Bergad, Laird W. (2007) The comparative histories of slavery in Brazil, Cuba, and the United States (Cambridge University Press, 2007) excerpt.

- Bethell, Leslie (1970). The Abolition of the Brazilian Slave Trade: Britain, Brazil and the Slave Trade Question, 1807–1869. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521075831.

- Conrad, Robert E. (1972). Destruction of Brazilian Slavery, 1850–1888. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02139-8.

- Ferguson, Niall (2012). Civilization – The Six Killer Apps of Western Power. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-141-04458-3.

- Klein, Herbert S. Klein and Francisco Vidal Luna, Slavery in Brazil (Cambridge University Press, 2010)

- Marquese, Rafael, Tâmis Parron, and Márcia Berbel. "Slavery and politics: Brazil and Cuba, 1790-1850." (2016). online

- Schwartz, Stuart B. (1985). Sugar Plantations in the Formation of Brazilian Society: Bahia, 1550–1835. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31399-6.

- Schwartz, Stuart B. (1996). Slaves, Peasants, and Rebels: Reconsidering Brazilian Slavery. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06549-2.

- Araujo, Ana (2015). African Heritage and Memories of Slavery in Brazil and the South Atlantic World. Cambria Press. ISBN 9781604978926.

.svg.png.webp)