History of the European Union

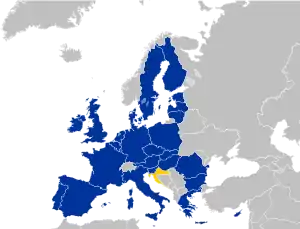

The European Union is a geo-political entity covering a large portion of the European continent. It is founded upon numerous treaties and has undergone expansions and secessions that have taken it from six member states to 27, a majority of the states in Europe.

| History of the European Union |

|---|

|

|

|

Since the beginning of the institutionalised modern European integration in 1948, the development of the European Union has been based on a supranational foundation that would "make war unthinkable and materially impossible"[1][2] and reinforce democracy amongst its members[3] as laid out by Robert Schuman and other leaders in the Schuman Declaration (1950) and the Europe Declaration (1951). This principle was at the heart of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) (1951), the Treaty of Paris (1951), and later the Treaty of Rome (1958) which established the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC). The Maastricht Treaty (1992) created the European Union with its pillars system, including foreign and home affairs alongside the European Communities. This in turn led to the creation of the single European currency, the euro (launched 1999). The ECSC expired in 2002. The Maastricht Treaty has been amended by the treaties of Amsterdam (1997), Nice (2001) and Lisbon (2007), the latter merging the three pillars into a single legal entity, though the EAEC has maintained a distinct legal identity despite sharing members and institutions.

Development of Europe as a region

Europe as a continent

The known world in Ancient Greece was differentiated into three landmasses Asia, "Libya" (Africa) and Europe, giving rise to identifying the European landmass as a coherent area, a continent.

Roman Europes

The European landmass was populated and territorialized by many long before its conceptualization as a coherent continent. But the Roman Empire, an empire built on the Hellenistic world and Alexandrian Empire, Ancient Egypt, the Levant and North Africa, became the first state to control the whole Mediterranean Basin and also large parts, particularly the Southern and Western parts of the European landmass. This historic prominence in the Mediterranean Basin and Europe has been invoked by states that came after it, claiming succession to Roman authority and to legitimate their rule over lands throughout the former Roman eucomene, and therefore also in Europe, particularly in Western Europe, the lands of the later Western Roman Empire of latin Rome. The latter established Western Europe as a coherent and independent political area of Europe, which has taken sometimes prominence, as simply the West, over the concept of Europe. Similarly other concepts for Europe as a coherent political space have been used, such as for example Frangistan.

The claims for the succession of the control over the West, after the fall of Western Rome in 476 developed into the concept of translatio imperii ("transfer of rule") through the King of Italy, enabling claims by the Goths, Lombards, Frankish Empire (481/800–843) and Holy Roman Empire (800/962–1806).[lower-alpha 1] Furtherore, during and after the Roman Empire the concept renovatio imperii ("restoration of the empire") was employed,[6] particularly in the forms of the religiously inspired Imperium Christianum ("christian empire"),[7][8] and later the Reichsidee ("imperial idea"),[9] to establish and sustain a coherent political region. As such the position and extand of influence of the Papacy over a range of European lands has been a force, while not exclusively European, capable of rallying European powers under a common Christian identity.[10][11][12][13] That said, some European powers, such as France (after the installment of the Holy Roman Empire with East Francia) and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth challenged the Western Roman authority through the Western Schism and the Italian Wars, while England, the Dutch Republic, Prussia, the Swedish Empire and Denmark–Norway also challenged the Papal one with Protestant Reformation.

The Greek Eastern Rome, also called Byzantine Empire, remained long after the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire, sustaining a coherent political space also over large areas of Europe, particularly of (South-) Eastern Europe, or simply the East, giving rise to the other major particular Europe. With the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire in 1453, the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Tsardom, and ultimately the Empire (1547–1917), with Moscow as the so-called Third Rome, used claims of inheritance of the eastern Roman Empire to legitimate their rule over larger areas of Europe, though not exclusively.[14]

- The Frankish Empire has had a symbolic relevance for the building of Europe since the 20th century: Charlemagne is often regarded as the "Father of Europe" and a similarity between the borders of Charlemagne's Empire and that of the European Economic Community was made explicit during the 1965 Aachen exhibition sponsored by the Council of Europe.[4] Kikuchi Yoshio (菊池良生) of Meiji University suggested that the notion of Holy Roman Empire as a federal political entity influenced the later structural ideas of the European Union.[5]

Other Europes

But also other polities of Europe have established, independently from Rome and Byzantine, their European realms, such as a range of pre-Roman or pre-Christian Greek, Germanic, Celtic, Slavic and Hungarian powers, Khanates, or Al-Andalus and the Sicilian Emirate.

Ideas of European unity before 1948

Apart from the ideas of federation, confederation, or customs union such as Winston Churchill's 1946 call for a "United States of Europe", the original development of the European Union was based on a supranational foundation that would "make war unthinkable and materially impossible"[1][2] A peaceful means of some consolidation of European territories used to be provided by dynastic unions; less common were country-level unions, such as the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Austro-Hungarian Empire.[15]

In the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle of 1818, Tsar Alexander, as the most advanced internationalist of the day, suggested a kind of permanent European union and even proposed the maintenance of international military forces to provide recognised states with support against changes by violence.[16]

Pan-European political thought truly emerged during the 19th century, inspired by the liberal ideas of the French and American Revolutions. The following Napoleonic Wars and First French Empire (1804–1815), brought down the Holy Roman Empire, enabled nationalism and following the Congress of Vienna,[17] the ideals of internationalism like with Immanuel Kant and European unity flourished across the continent, especially in the writings of Wojciech Jastrzębowski (1799–1882)[18] or Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–1872).[19] The term United States of Europe (French: États-Unis d'Europe) was used at that time by Victor Hugo (1802–1885) during a speech at the International Peace Congress held in Paris in 1849:

A day will come when all nations on our continent will form a European brotherhood ... A day will come when we shall see ... the United States of America and the United States of Europe face to face, reaching out for each other across the seas.[20]

From World War I to World War II

During the interwar period, the consciousness that national markets in Europe were interdependent though confrontational, along with the observation of a larger and growing US market on the other side of the ocean, nourished the urge for the economic integration of the continent.[21] In 1920, advocating the creation of a European economic union, the British economist John Maynard Keynes wrote that "a Free Trade Union should be established ... to impose no protectionist tariffs whatever against the produce of other members of the Union."[22] During the same decade, the Austrian Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, in light of the dissolution of the Habsburg Empire, imagined as one of the first modern political unions of Europe, founded the Pan-Europa Movement.[23] His ideas influenced his contemporaries, among whom was then-Prime Minister of France Aristide Briand. In 1929, the latter gave a speech in favour of a European Union before the assembly of the League of Nations, the precursor of the United Nations.[24]

World War II (1939-1945)

World War II from 1939 to 1945 demonstrated more than ever the horrors of war, but particularly also of extremism, of discrimination and of genocide. As with devastating wars before, there was a desire to ensure it could never happen again, particularly with the war bringing the world nuclear weapons. Most European countries failed to maintain their Great Power status, with the exception of the Soviet Union, which became a superpower after World War II and maintained that status for 45 years. This left two rival ideologically opposed superpowers.[25]

After World War I, but particularly following World War II, internationalism was gaining, with the creation of the Bretton Woods System in 1944, the United Nations in 1945 and the French Union (1946–1958), the latter directing decolonization by possibly integrating its colonies into a European community.[26][27] In this light European integration was already viewed by its proponents as an antidote to the extreme nationalism which had devastated parts of the continent.[28]

With war still raging, the Ventotene prison Manifesto of 1941 by Altiero Spinelli propagated European integration through the Italian Resistance and after 1943 through the European Federalist Movement. In March 1943, in a radio address, the United Kingdom's leader Sir Winston Churchill spoke warmly of "restoring the true greatness of Europe" once victory had been achieved, and mused on the post-war creation of a "Council of Europe" which would bring the European nations together to build peace.[29][30] in 1943 for a post-war "Council of Europe"[29][30]

Towards the end of World War II, the Three Allied Powers discussed during the Tehran Conference and the ensuing 1943 Moscow Conference the plans to establish joint institutions. This led to a decision at the Yalta Conference in 1944 to include Free France as the Fourth Allied Power and to form a European Advisory Commission, later replaced by the Council of Foreign Ministers and the Allied Control Council, following the German surrender and the Potsdam Agreement in 1945.

Aftermath (1945-1948)

After the war on 19 September 1946 Churchill went further as a civilian, after leaving office, at the University of Zürich, calling for a United States of Europe. Coincidentally[31] parallel to his speech the Hertenstein Congress in the Lucerne Canton was being held, resulting in the Union of European Federalists.[32] Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, who successfully established during the interwar period the oldest organization for European integration, the Paneuropean Union, founded in June 1947 the European Parliamentary Union (EPU). To ensure Germany could never threaten the peace again, its heavy industry was partly dismantled (See: Allied plans for German industry after World War II) and its main coal-producing regions were either awarded to neighbouring countries (Silesia), managed as separate directly by an occupying power (Saarland)[33] or put under international control (Ruhr area).[34][35]

The growing rift among the Four Powers became evident as a result of the rigged 1947 Polish legislative election which constituted an open breach of the Yalta Agreement, followed by the announcement of the Truman Doctrine on 12 March 1947. On 4 March 1947 France and the United Kingdom signed the Treaty of Dunkirk for mutual assistance in the event of future military aggression in the aftermath of World War II against any of the pair. The rationale for the treaty was the threat of a potential future military attack, specifically a Soviet one in practice, though publicised under the disguise of a German one, according to the official statements. Immediately following the February 1948 coup d'état by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, the London Six-Power Conference was held, resulting in the Soviet boycott of the Allied Control Council and its incapacitation, an event marking the beginning of the Cold War. The remainder of the year 1948 marked the beginning of the institutionalised modern European integration.

Initial years (1948–57)

With the start of the Cold War, the Treaty of Brussels was signed in 1948 establishing the Western Union (WU) as the first organisation, followed by the International Authority for the Ruhr. In the same year, the Organization for European Economic Co-operation, the predecessor of the OECD, was also founded to manage the Marshall Plan; the Eastern Bloc responded with establishing the Comecon.

A pivotal moment in European integration was the Hague Congress of May 1948, as it led to the creation of the European Movement International, the College of Europe[36] and most importantly to the founding of the Council of Europe on the 5th of May 1949 (now known as Europe Day). The Council of Europe was the first institution to bring the sovereign nations of Western Europe together, raising great hopes and fevered debates in the following two years for further European integration. It has since been a broad forum to further cooperation and shared issues, achieving things like the 1950-signed European Convention on Human Rights.

Essential for the actual birth of the institutions of the EU was the 9th of May 1950 Schuman Declaration (on the day after the fifth Victory Day, today's Europe day – of the EU). On the basis of that speech, France, Italy, the Benelux countries (Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg) together with West Germany signed the Treaty of Paris (1951) creating the European Coal and Steel Community the following year; this took over the role of the International Authority for the Ruhr[34] and lifted some restrictions on German industrial productivity. It gave birth to the first institutions, such as the High Authority (now the European Commission) and the Common Assembly (now the European Parliament). The first presidents of those institutions were Jean Monnet and Paul-Henri Spaak respectively. The founding fathers of the European Union understood that coal and steel were the two industries essential for waging war, and believed that by tying their national industries together, a future war between their nations became much less likely.[37] Backed by the Marshall Plan with large funds coming from the United States since 1948, the ECSC became a milestone organization, enabling European economic development and integration and being the origin of the main institutions of the EU such as the European Commission and Parliament.[38]

The formation of the European Coal and Steel Community was advanced by American Secretary of State George C. Marshall. His namesake plan to rebuild Europe in the wake of World War II contributed more than $100 billion in today's dollars to the Europeans, helping to feed Europeans, deliver steel to rebuild industries, provide coal to warm homes, and construct dams to help provide power. In doing so, the Marshall Plan encouraged the integration of European powers into the European Coal and Steel Community, the precursor to present-day European Union, by illustrating the effects of economic integration and the need for coordination. The potency of the Marshall Plan caused former German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt to remark in 1997 that "America should not forget that the development of the European Union is one of its greatest achievements. Without the Marshall Plan it perhaps would never have come to that."[39][40]

Paralleling Schuman, the Pleven Plan of 1951 tried, but failed to tie the institutions of the developing European community under the European Political Community, which was to include the also proposed European Defence Community, an alternative to West Germany joining NATO which was established 1949 under the Truman Doctrine. In 1954 the Western European Union was founded, after NATO took over competences from the WU, and West Germany joined. This prompted the Soviet Union to form the Warsaw Pact in 1955, allowing it to enforce its standing in Eastern Europe.

The attempt to turn the Saar protectorate into a "European territory" was rejected by a referendum in 1955. The Saar was to have been governed by a statute supervised by a European Commissioner reporting to the Council of Ministers of the Western European Union.

After the failed attempts at creating defence (European Defence Community) and political communities (European Political Community), leaders met at the Messina Conference and established the Spaak Committee which produced the Spaak report. The report was accepted at the Venice Conference (29 and 30 May 1956), which decided to organise an Intergovernmental Conference. The Intergovernmental Conference on the Common Market and Euratom focused on economic unity, leading to the Treaties of Rome being signed in 1957 - this established the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) among the members.[41]

1958–1972: Three communities

The two new communities were created separately from ECSC, although they shared the same courts and the Common Assembly. The executives of the new communities were called Commissions, as opposed to the "High Authority". The EEC was headed by Walter Hallstein (Hallstein Commission) and Euratom was headed by Louis Armand (Armand Commission) and then Étienne Hirsch. Euratom would integrate sectors in nuclear energy while the EEC would develop a customs union between members.[41][42][43]

Throughout the 1960s tensions began to show with France seeking to limit supranational power and rejecting the membership of the United Kingdom. However, in 1965 an agreement was reached to merge the three communities under a single set of institutions, and hence the Merger Treaty was signed in Brussels and came into force on 1 July 1967 creating the European Communities.[44] Jean Rey presided over the first merged Commission (Rey Commission).

While the political progress of the Communities was hesitant in the 1960s, this was a fertile period for European legal integration.[45] Many of the foundational legal doctrines of the Court of Justice were first established in landmark decisions during the 1960s and 1970s, above all in the Van Gend en Loos decision of 1963 that declared the "direct effect" of European law, that is to say, its enforceability before national courts by private parties.[46] Other landmark decisions during this period included Costa v ENEL, which established the supremacy of European law over national law[47] and the "Dairy Products" decision, which declared that general international law principles of reciprocity and retaliation were prohibited within the European Community.[48] All three of these judgments were made after the appointment of French judge Robert Lecourt in 1962, and Lecourt appears to have become a dominant influence on the Court of Justice over the 1960s and 1970s.[49]

1973–1993: Enlargement to Delors

After much negotiation, and following a change in the French Presidency, Denmark, Ireland and the United Kingdom (with Gibraltar) eventually joined the European Communities on 1 January 1973. This was the first of several enlargements which became a major policy area of the Union (see: Enlargement of the European Union).[50]

In 1979, the European Parliament held its first direct elections by universal suffrage. 410 members were elected, who then elected the first female President of the European Parliament, Simone Veil.[51]

A further enlargement took place in 1981 with Greece joining on 1 January, six years after applying. In 1982, Greenland voted to leave the Community after gaining home rule from Denmark (See also: Special member state territories and the European Union). Spain and Portugal joined (having applied in 1977) on 1 January 1986 in the third enlargement.[52]

Recently appointed Commission President Jacques Delors (Delors Commission) presided over the adoption of the European flag by the Communities in 1986. In the first major revision of the treaties since the Merger Treaty, leaders signed the Single European Act in February 1986. The text dealt with institutional reform, including extension of community powers – in particular in regarding foreign policy. It was a major component in completing the single market and came into force on 1 July 1987.[53] In 1987 Turkey formally applied to join the Community and began the longest application process for any country. After the 1988 Polish strikes and the Polish Round Table Agreement, the first small signs of opening in Central Europe appeared. The opening of a border gate between Austria and Hungary at the Pan-European Picnic on August 19, 1989 then set in motion a peaceful chain reaction, at the end of which there was no longer a GDR and the Eastern Bloc had disintegrated. Otto von Habsburg and Imre Pozsgay saw the event as an opportunity to test Mikhail Gorbachev`s reaction to an opening of the Iron Curtain.[54] In particular, it was examined whether Moscow would give the Soviet troops stationed in Hungary the command to intervene.[55] But with the mass exodus at the Pan-European Picnic, the subsequent hesitant behavior of the Socialist Unity Party of East Germany and the non-intervention of the Soviet Union broke the dams. So the bracket of the Eastern Bloc was broken and as a result the Berlin Wall fell together with the whole Iron Curtain.[56][57] Germany reunified and the door to enlargement to the former Eastern Bloc was opened (See also: Copenhagen Criteria).[58][59]

With a wave of new enlargements on the way, the Maastricht Treaty was signed on 7 February 1992 which established the European Union when it came into force the following year.

1993–2004: Creation

On 1 November 1993, under the third Delors Commission, the Maastricht Treaty became effective, creating the European Union with its pillar system, including foreign and home affairs alongside the European Community.[60][61] The 1994 European elections were held resulting in the Party of European Socialists maintaining their position as the largest party in Parliament. The Council proposed Jacques Santer as Commission President but he was seen as a second choice candidate, undermining his position. Parliament narrowly approved Santer but his commission gained greater support, being approved by 416 votes to 103. Santer had to use his new powers under Maastricht to flex greater control over his choice of Commissioners. They took office on 23 January 1995.[62]

On 30 March 1994, accession negotiations concluded with Austria, Sweden and Finland. Meanwhile, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein joined the European Economic Area (which entered into force on 1 January 1994), an organisation that allowed European Free Trade Association states to enter the Single European Market. The following year, the Schengen Agreement came into force between seven members, expanding to include nearly all others by the end of 1996. The 1990s also saw the further development of the euro. 1 January 1994 saw the second stage of the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union begin with the establishment of the European Monetary Institute and at the start of 1999 the euro as a currency was launched and the European Central Bank was established. On 1 January 2002, notes and coins were put into circulation, replacing the old currencies entirely.

During the 1990s, the conflicts in the Balkans gave impetus to developing the EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). The EU failed to react during the beginning of the conflict, and UN peacekeepers from the Netherlands failed to prevent the Srebrenica massacre (July 1995) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the largest mass murder in Europe since the Second World War. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) finally had to intervene in the war, forcing the combatants to the negotiation table. The early foreign policy experience of the EU led to foreign policy being emphasised in the Treaty of Amsterdam (which created the High Representative).[63]

However, any success was overshadowed by the budget crisis in March 1999. The Parliament refused to approve the Commission's 1996 community's budget on grounds of financial mismanagement, fraud and nepotism. With Parliament ready to throw them out, the entire Santer Commission resigned.[64][65] The post-Delors mood of euroscepticism became entrenched with the Council and Parliament constantly challenging the Commission's position in coming years.[66]

In the following elections, the Socialists lost their decades-old majority to the new People's Party and the incoming Prodi Commission was quick to establish the new European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF).[67] Under the new powers of the Amsterdam Treaty, Prodi was described by some as the 'First Prime Minister of Europe'.[68] On 4 June, Javier Solana was appointed Secretary General of the Council and the strengthened High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy admitted the intervention in Kosovo – Solana was also seen by some as Europe's first Foreign Minister.[69] The Nice Treaty was signed on 26 February 2001 and entered into force on 1 February 2003 which made the final preparations before the 2004 enlargement to 10 new members.

2004–2007: The great enlargement and consolidation

On 10–13 June 2004, the 25 member states participated in the largest trans-national election in history (with the second largest democratic electorate in the world). The result of the sixth Parliamentary election was a second victory for the European People's Party-European Democrats group. It also saw the lowest voter turnout of 45.5%, the second time it had fallen below 50%.[70] On 22 July 2004, José Manuel Barroso was approved by the new Parliament as the next Commission President. However, his new team of 25 Commissioners faced a tougher road. With Parliament raising objections to a number of his candidates he was forced to withdraw his selection and try once more. The Prodi Commission had to extend their mandate to 22 November after the new line-up of commissioners was finally approved.[71]

A proposed constitutional treaty was signed by plenipotentiaries from EU member states on 28 October 2004. The document was ratified in most member states, including two positive referendums. The referendums that were held in France and the Netherlands failed however, killing off the treaty. The European Council agreed that the constitution proposal would be abandoned, but most of its changes would be retained in an amending treaty. On 13 December 2007 the treaty was signed, containing opt-outs for the more eurosceptic members and no state-like elements. The Lisbon treaty finally came into force on 1 December 2009. It created the post of President of the European Council and significantly expanded the post of High Representative. After much debate about what kind of person should be President, the European Council agreed on a low-key personality and chose Herman Van Rompuy while foreign policy-novice Catherine Ashton became High Representative.

The 2009 elections again saw a victory for the European People's Party, despite losing the British Conservatives who formed a smaller eurosceptic European Conservatives and Reformists grouping with other anti-federalist right wing parties. Parliament's presidency was once again divided between the People's Party and the Socialists, with Jerzy Buzek elected as the first President of the European Parliament from an ex-communist country. Barroso was nominated by the Council for a second term and received backing from EPP who had declared him as their candidate before the elections. However, the Socialists and Greens led the opposition against him despite not agreeing on an opposing candidate. Parliament finally approved Barroso II, though once more several months behind schedule.

In 2007, the fifth enlargement completed with the accession of Bulgaria and Romania on 1 January 2007. Also, in 2007 Slovenia adopted the euro,[72] Malta and Cyprus in 2008[73] and Slovakia in 2009.

2008–2016: European crisis

However trouble developed with existing members as the eurozone entered its first recession in 2008.[74] Members cooperated and the ECB intervened to help restore economic growth and the euro was seen as a safe haven, particularly by those outside such as Iceland.[75][76][77] With the risk of a default in Greece, Ireland, Portugal and other members in late 2009–10, eurozone leaders agreed to provisions for loans to member states who could not raise funds. Accusations that this was a U-turn on the EU treaties, which rule out any bail out of a euro member in order to encourage them to manage their finances better, were countered by the argument that these were loans, not grants, and that neither the EU nor other Member States assumed any liabilities for the debts of the aided countries. With Greece struggling to restore its finances, other member states also at risk and the repercussions this would have on the rest of the eurozone economy, a loan mechanism was agreed. The crisis also spurred consensus for further economic integration and a range of proposals such as a European Monetary Fund or federal treasury.[78][79][80]

The European Union received the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize for having "contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe."[81][82] The Nobel Committee stated that "that dreadful suffering in World War II demonstrated the need for a new Europe [...] today war between Germany and France is unthinkable. This shows how, through well-aimed efforts and by building up mutual confidence, historical enemies can become close partners."[83] The Nobel Committee's decision was subject to considerable criticism.[84]

On 1 July 2013, Croatia joined the EU, and on 1 January 2014 the French Indian Ocean territory of Mayotte was added as an outermost region.[85]

2016–2020: Brexit

.jpg.webp)

On 23 June 2016, the citizens of the United Kingdom voted to withdraw from the European Union in a referendum and subsequently became the first and to date only member to trigger Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU). The vote was in favour of leaving the EU by a margin of 51.9% in favour to 48.1% against.[86] The UK's withdrawal was completed on 31 January 2020.

2020–2022: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

.jpg.webp)

After the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic the EU leaders agreed for the first time to emit common debt to finance the European Recovery Program called Next Generation EU (NGEU).[87]

2022–present: Impact of the Russo-Ukrainian War

On 24 February 2022, after massing near the borders of Ukraine, the Russian Armed Forces undertook a full-scale invasion of Ukraine.[88][89]

The European Union imposed heavy sanctions on Russia and agreed on a pooled military aid package to Ukraine for lethal weapons funded via the European Peace Facility off-budget instrument.[90][91] Likewise, neighbouring EU member countries received a mass influx of Ukrainian refugees fleeing the conflict over the course of the first weeks of the war.[92] The conflict exposed the EU energy dependency on Russia, deemed as a supplier "explicitly" threatening the EU.[93] This development injected a sense of urgency in the switch towards alternative energy suppliers and further development of clean energy sources.[93]

Reform

Multi-speed Europe is a concept of differentiated integration currently in operation that has recently been given renewed emphasis by a team of independent experts[94] in a report presented at a council meeting in Brussels in September of 2023.[95][96] "France and Germany are pushing for a larger EU reform before any new member joins the bloc."[97]

Structural evolution

Since the end of World War II, sovereign European countries have entered into treaties and thereby co-operated and harmonised policies (or pooled sovereignty) in an increasing number of areas, in the European integration project or the construction of Europe (French: la construction européenne). The following timeline outlines the legal inception of the European Union (EU)—the principal framework for this unification. The EU inherited many of its present responsibilities from the European Communities (EC), which were founded in the 1950s in the spirit of the Schuman Declaration.

| Legend: S: signing F: entry into force T: termination E: expiry de facto supersession Rel. w/ EC/EU framework: de facto inside outside |

[Cont.] | ||||||||||||||||

| (Pillar I) | |||||||||||||||||

| European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or Euratom) | [Cont.] | ||||||||||||||||

| European Economic Community (EEC) | |||||||||||||||||

| Schengen Rules | European Community (EC) | ||||||||||||||||

| 'TREVI' | Justice and Home Affairs (JHA, pillar II) | ||||||||||||||||

| [Cont.] | Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCC, pillar II) | ||||||||||||||||

Anglo-French alliance |

[Defence arm handed to NATO] | European Political Co-operation (EPC) | Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP, pillar III) | ||||||||||||||

| [Tasks defined following the WEU's 1984 reactivation handed to the EU] | |||||||||||||||||

| [Social, cultural tasks handed to CoE] | [Cont.] | ||||||||||||||||

- Although not EU treaties per se, these treaties affected the development of the EU defence arm, a main part of the CFSP. The Franco-British alliance established by the Dunkirk Treaty was de facto superseded by WU. The CFSP pillar was bolstered by some of the security structures that had been established within the remit of the 1955 Modified Brussels Treaty (MBT). The Brussels Treaty was terminated in 2011, consequently dissolving the WEU, as the mutual defence clause that the Lisbon Treaty provided for EU was considered to render the WEU superfluous. The EU thus de facto superseded the WEU.

- Plans to establish a European Political Community (EPC) were shelved following the French failure to ratify the Treaty establishing the European Defence Community (EDC). The EPC would have combined the ECSC and the EDC.

- The European Communities obtained common institutions and a shared legal personality (i.e. ability to e.g. sign treaties in their own right).

- The treaties of Maastricht and Rome form the EU's legal basis, and are also referred to as the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), respectively. They are amended by secondary treaties.

- Between the EU's founding in 1993 and consolidation in 2009, the union consisted of three pillars, the first of which were the European Communities. The other two pillars consisted of additional areas of cooperation that had been added to the EU's remit.

- The consolidation meant that the EU inherited the European Communities' legal personality and that the pillar system was abolished, resulting in the EU framework as such covering all policy areas. Executive/legislative power in each area was instead determined by a distribution of competencies between EU institutions and member states. This distribution, as well as treaty provisions for policy areas in which unanimity is required and qualified majority voting is possible, reflects the depth of EU integration as well as the EU's partly supranational and partly intergovernmental nature.

See also

- Timeline of European Union history

- Enlargement of the European Union

- History of the euro

- History of the Common Security and Defence Policy

- List of European Councils

- List of presidents of the institutions of the European Union

- Founding fathers of the European Union

- History of the European Union in Brussels

- History of the location of EU institutions

- History of Europe

- House of European History

- Virtual Centre for Knowledge on Europe Multimedia source collections on EU History

- Wider European history between World War II and the fall of Communism in Europe 1945–1992

- End of World War II in Europe

- Cold War

- Revolutions of 1989

- German reunification

- Yugoslavia and the European Economic Community

- Breakup of Yugoslavia

- Wider European history after the creation of the European Union

References

- "Schuman Project". schuman.info.

- "Schuman Project". schuman.info.

- "Schuman Project". schuman.info.

- Story, Joanna (2005). Charlemagne: Empire and Society. Manchester University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-7190-7089-1.

- Kikuchi (菊池), Yoshio (良生) (2003). 神聖ローマ帝国. p. 264. ISBN 978-4-06-149673-6.

- Corbet, Patrick (2002). "Renovatio imperii romanorum". In Vauchez, André (ed.). Oxford Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. James Clarke & Co. ISBN 978-0-227-67931-9.

- Folz, Robert (1969). The concept of empire in Western Europe from the fifth to the fourteenth century. London: Edward Arnold. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7131-5451-1. OCLC 59622.

- Gorp, Bouke Van; Renes, Hans (2007). "A European Cultural Identity? Heritage and shared histories in the European Union" (PDF). Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie. 98 (3): 411. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2007.00406.x. ISSN 1467-9663. S2CID 55529057. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

For the last two thousand years, the Christian church has attempted to unify Europe in cultural terms. Christianity did not originate in Europe but, building upon the organisation of the Roman Empire, has tried throughout the Middle Ages to become a Europe-wide organisation.

- Schramm, Percy E. (1957). Kaiser, Rom und Renovatio; Studien zur Geschichte des römischen Erneuerungsgedankens vom Ende des karolingischen Reiches bis zum Investiturstreit (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. p. 143. OCLC 15021725.

- Pagden & Hamilton 2002, p. 89.

- Mather 2006, pp. 16–18.

- Nelsen, Brent F.; Guth, James L. (2015). Religion and the Struggle for European Union: Confessional Culture and the Limits of Integration. Georgetown University Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-62616-070-5.

- Perkins, Mary Anne (2004). Christendom and European Identity: The Legacy of a Grand Narrative Since 1789. Walter de Gruyter. p. 341. ISBN 978-3-11-018244-6.

- Skolimowska, Anna (2018). Perceptions of the European Union's Identity in International Relations. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-00560-9.

- "The World Factbook". cia.gov. 16 February 2022.

- R. R. Palmer. A History of the Modern World. p. 461.

- Ghervas, Stella (2014). "Antidotes to Empire: From the Congress System to the European Union". In Boyer, John W.; Molden, Berthold (eds.). EUtROPEs. The Paradox of European Empire. University of Chicago Center in Paris. pp. 49–81. ISBN 978-2-9525962-6-8.

- Pinterič, Uroš; Prijon, Lea (2013). European Union in 21st Century. University of SS. Cyril and Methodius, Faculty of Social Sciences. ISBN 978-80-8105-510-2.

- Smith, Denis Mack (2008). Mazzini. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17712-1.

- Metzidakis, Angelo (1994). "Victor Hugo and the Idea of the United States of Europe". Nineteenth-Century French Studies. 23 (1/2): 72–84. JSTOR 23537320.

- Kaiser & Varsori 2010, p. 140.

- John Maynard Keynes, Economic Consequences of the Peace, New York: Harcourt, Brace & Howe, 1920, pp. 265–66.

- Rosamond, Ben (2000), Theories of European Integration, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 21–22, OCLC 442641648

- Weigall, David; Stirk, Peter M. R., eds. (1992), The Origins and Development of the European Community, Leicester: Leicester University Press, pp. 11–15, ISBN 9780718514280

- Europe in ruins in the aftermath of the Second World War ena.lu

- Hansen, Peo; Jonsson, Stefan (2011). "Bringing Africa as a 'Dowry to Europe'". Interventions. 13 (3): 443–463 (459). doi:10.1080/1369801X.2011.597600. S2CID 142558321.

-

Schuman, Robert. "Robert Schuman's proposal of 9 May 1950: founding of the means of gathering the European nations into a peace-enhancing Union". Translated by Price, D Heilbron. Schuman Project. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

The establishment of [the proposed European Coal and Steel Community], open to all countries willing to take part, and eventually capable of providing all the member countries with the basic elements of industrial production on the same terms, will cast the real foundation for their economic unification. [...] This production would be offered to the world as a whole, without distinction or exception, with the aim of raising living standards and promoting peace as well as fulfilling one of Europe's essential tasks — the development of the African continent.

- "The political consequences". CVCE. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

Der Gedanke der europäischen Einheit, die vielen als Schutzwall gegen ein Wiedererstarken des Nationalismus gilt, findet zahlreiche Anhänger.

[The idea of European unity, which for many equated to a barrier against a resurgence of nationalism, found numerous supporters.] - Klos, Felix (2017). Churchill's Last Stand: The Struggle to Unite Europe. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-78673-292-7.

- Churchill, Winston (21 March 1943). "National Address". The International Churchill Society.

- "Union of European Federalists (UEF): Churchill and Hertenstein". Union of European Federalists (UEF). Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- "Ein britischer Patriot für Europa: Winston Churchills Europa-Rede, Universität Zürich, 19. September 1946" [A British Patriot for Europe: Winston Churchill's Speech on Europe University of Zurich, 19 September 1946]. Zeit Online. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica (12 September 2019). "Saarland". Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- Yoder, Amos (July 1955). "The Ruhr Authority and the German Problem". Review of Politics. Cambridge University Press. 17 (3): 345–358. doi:10.1017/S0034670500014261. S2CID 145465919.

-

- French proposal regarding the detachment of German industrial regions 8 September 1945

France, Germany and the Struggle for the War-making Natural Resources of the RhinelandLetter from Konrad Adenauer to Robert Schuman (26 July 1949) Warning him of the consequences of the dismantling policy. (requires Flash Player)

Letter from Ernest Bevin to Robert Schuman (30 October 1949) British and French foreign ministers. Bevin argues that they need to reconsider the Allies' dismantling policy in the occupied zones (requires Flash Player)

- French proposal regarding the detachment of German industrial regions 8 September 1945

- Dieter Mahncke; Léonce Bekemans; Robert Picht, eds. (1999). The College of Europe. Fifty Years of Service to Europe. Bruges: College of Europe. ISBN 978-90-804983-1-0. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016.

- "A peaceful Europe – the beginnings of cooperation". European Commission. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- Blocker, Joel (9 April 2008). "Europe: How The Marshall Plan Took Western Europe From Ruins To Union". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Schmidt, Helmut (6 June 1997). "Helmut Schmidt über den Marshallplan und die europäische Einheit: Mit voller Kraft ins nächste Jahrhundert" (in German). Die Zeit.

Und Amerika sollte nicht vergessen, daß die Entstehung der Europäischen Union eine seiner größten Leistungen ist. Ohne den Marshallplan wäre es vielleicht nie dazu gekommen.

- Blocker, Joel (9 May 1997). "Europe: How The Marshall Plan Took Western Europe From Ruins To Union". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

Witness the recent words of former German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt: 'The United States ought not to forget that the emerging European Union is one of its greatest achievements: it would never have happened without the Marshall Plan.' [The "vielleicht" in the original quote is missing in this translation.]

- A peaceful Europe – the beginnings of cooperation europa.eu

- A European Atomic Energy Community ena.lu

- A European Customs Union ena.lu

- Merging the executives ena.lu

- Lecourt, Robert (1976). L'Europe des juges. Bruxelles, Bruylant. Stein, Eric (1981). 'Lawyers, Judges, and the Making of a Transnational Constitution.' American Journal of International Law 75(1): 1–27. Weiler, Joseph H. H. (1991). 'The Transformation of Europe.' Yale Law Journal 100: 2403–2483.

- ECJ Case 26/62

- ECJ Case 6/64

- ECJ Cases 90&91/63, Commission v Luxembourg & Belgium. See e.g. Phelan, William (2016). 'Supremacy, Direct Effect, and Dairy Products in the Early History of European law.' International Journal of Constitutional Law 14: 6–25.

- W. Phelan, Great Judgments of the European Court of Justice: Rethinking the Landmark Decisions of the Foundational Period (Cambridge, 2019)

- The first enlargement cvce.eu

- The new European Parliament cvce.eu

- Negotiations for enlargement cvce.eu

- Single European Act cvce.eu

- Miklós Németh in Interview, Austrian TV - ORF "Report", 25 June 2019

- „Der 19. August 1989 war ein Test für Gorbatschows“ (German - August 19, 1989 was a test for Gorbachev), in: FAZ 19 August 2009.

- Michael Frank: Paneuropäisches Picknick – Mit dem Picknickkorb in die Freiheit (German: Pan-European picnic - With the picnic basket to freedom), in: Süddeutsche Zeitung 17 May 2010.

- Ludwig Greven "Und dann ging das Tor auf", in Die Zeit, 19 August 2014.

- The fall of the Berlin Wall ena.lu

- Andreas Rödder, Deutschland einig Vaterland – Die Geschichte der Wiedervereinigung (2009).

- 1993 europa.eu

- Characteristics of the Treaty on European Union cvce.eu

- "The crisis of the Santer Commission". Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l'Europe (CVCE). Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- The Treaty of Amsterdam ena.lu

- Ringer, Nils F. (February 2003). "The Santer Commission Resignation Crisis" (PDF). University of Pittsburgh. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 August 2006. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- Hoskyns, Catherine; Michael Newman (2000). Democratizing the European Union: Issues for the twenty-first Century (Perspectives on Democratization). Manchester University Press. pp. 106–7. ISBN 978-0-7190-5666-6.

- Topan, Angelina (30 September 2002). "The resignation of the Santer-Commission: the impact of 'trust' and 'reputation'". European Integration online Papers. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- "EU Budget Fraud". politics.co.uk. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- Prodi to Have Wide, New Powers as Head of the European Commission iht.com 16 April 1999

- Javier Solana/Spain: Europe's First Foreign Minister? businessweek.com

- Vote EU 2004 news.bbc.co.uk

- The new commission – some initial thoughts Archived 23 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine bmbrussels.b

- "Slovenia clear to adopt the euro". British Broadcasting Corporation. 16 June 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- "Cyprus and Malta set to join Eurozone in 2008". euractiv.com. 16 May 2007. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- EU data confirms eurozone's first recession Archived 30 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, EUbusiness.com, 8 January 2009

- "European leaders agree crisis rescue at summit". Eubusiness.com. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- Oakley, David and Ralph Atkins (17 September 2009) Eurozone shows its strength in a crisis, Financial Times

- Iceland to be fast-tracked into the EU, the Guardian

- Willis, Andrew (25 March 2010) Eurozone leaders agree on Franco-German bail-out mechanism, EU Observer

- Eurozone overhaul Die Zeit on Presseurop, 12 February 2010

- Plans emerge for 'European Monetary Fund' EU Observer

- The Nobel Peace Prize 2012, Nobelprize.org, 12 October 2012, retrieved 12 October 2012

- "Nobel Committee Awards Peace Prize to E.U.", New York Times, 12 October 2012, retrieved 12 October 2012

- The Nobel Peace Prize for 2012, Nobelprize.org, 12 October 2012, retrieved 12 October 2012

- Gaspers, Jan (December 2012). "The European Union and the Nobel Peace Prize: A Criteria-Based Assessment" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- "EUROPEAN COUNCIL DECISION of 11 July 2012 amending the status of Mayotte with regard to the European Union". europa.eu.

- "Labour leadership & Hammond in China – BBC News". Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- "Recovery plan for Europe". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- "Russia-Ukraine war: humanitarian corridor opened from Sumy; Moscow threatens to cut gas supplies to Europe". theguardian.com. theguardian.com. 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- "In pictures: Russia invades Ukraine". cnn.com. cnn.com. 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- Deutsch, Jillian; Pronina, Lyubov (27 February 2022). "EU Approves 450 Million Euros of Arms Supplies for Ukraine". Bloomberg.com.

- "Chelsea's oligarch owner is selling. Will scrutiny of other Premier League owners follow?". washingtonpost.com. washingtonpost.com. 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- Micinski, Nicholas R. (16 March 2022). "The E.U. granted Ukrainian refugees temporary protection. Why the different response from past migrant crises?". Washington Post.

- "EU unveils plan to reduce Russia energy dependency". dw.com. 8 March 2022.

- Amt, Auswärtiges. "German-French working group of experts on EU institutional reforms". German Federal Foreign Office. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- red, ORF at/Agenturen (19 September 2023). "Expertengruppe empfiehlt umfangreiche EU-Reformen". news.ORF.at (in German). Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- Brzozowski, Alexandra; Pugnet, Aurélie (19 September 2023). "Germany, France make EU reform pitch ahead of enlargement talks". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- Noyan, Oliver (23 June 2023). "EU reform: France, Germany confident on reaching agreement this year". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

Further reading

- Anderson, P. The New Old World (Verso 2009) ISBN 978-1-84467-312-4

- Berend, Ivan T. The History of European Integration: A New Perspective. (Routledge, 2016).

- Blair, Alasdair. The European Union since 1945 (Routledge, 2014).

- Chaban, N. and M. Holland, eds. Communicating Europe in Times of Crisis: External Perceptions of the European Union (2014).

- Dedman, Martin. The origins and development of the European Union 1945-1995: a history of European integration (Routledge, 2006).

- De Vries, Catherine E. "Don't Mention the War! Second World War Remembrance and Support for European Cooperation." JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies (2019).

- Dinan, Desmond. Europe recast: a history of European Union (2nd ed. Palgrave Macmillan), 2004 excerpt.

- Fimister, Alan. Robert Schuman: Neo-Scholastic Humanism and the Reunification of Europe (2008)

- Heuser, Beatrice. Brexit in History: Sovereignty or a European Union? (2019) excerpt also see online review

- Hobolt, Sara B. "The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent." Journal of European Public Policy (2016): 1–19.

- Jorgensen, Knud Erik, et al., eds. The SAGE Handbook of European Foreign Policy (Sage, 2015).

- Kaiser, Wolfram. "From state to society? The historiography of European integration." in Michelle Cini, and Angela K. Bourne, eds. Palgrave Advances in European Union Studies (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2006). pp 190–208.

- Kaiser, W.; Varsori, A. (2010). European Union History: Themes and Debates. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-28150-9.

- Koops, TJ. and G. Macaj. The European Union as a Diplomatic Actor (2015).

- McCormick, John. Understanding the European Union: a concise introduction (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

- Mather, J. (2006). Legitimating the European Union: Aspirations, Inputs and Performance. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-62562-4.

- May, Alex. Britain and Europe since 1945 (1999).

- Marsh, Steve, and Hans Mackenstein. The International Relations of the EU (Routledge, 2014).

- Milward, Alan S. The Reconstruction of Western Europe: 1945–51 (Univ. of California Press, 1984)

- Pagden, Anthony; Hamilton, Lee H. (2002). The Idea of Europe: From Antiquity to the European Union. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79552-4.

- Pasture, Patrick (2015). Imagining European unity since 1000 AD. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137480460.

- Patel, Kiran Klaus, and Wolfram Kaiser. "Continuity and change in European cooperation during the twentieth century." Contemporary European History 27.2 (2018): 165–182. online

- Smith, M.L.; Stirk, P.M.R., eds. (1990). Making The New Europe: European Unity and the Second World War (1st UK ed.). London: Pinter Publishers. ISBN 0-86187-777-2.

- Stirk, P.M.R., ed. (1989). European Unity in Context: The Interwar Period (1st ed.). London: Pinter Publishers. ISBN 9780861879878.

- Young, John W. Britain, France, and the unity of Europe, 1945–1951 (Leicester University, 1984).

External links

- History of the EU Official Europa website

- CLIOH-WORLD CLIOH-WORLD: Network of Universities supported by the European Commission (LLP-Erasmus) for the researching, teaching and learning of the history of the EU, including History of EU Integration, EU-Turkey dialogue, and linking to world history.

- An Outline of the Emergence of the European Union

.jpg.webp)