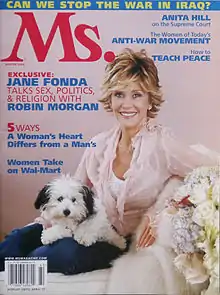

Jane Fonda

Jane Seymour Fonda[2] (born December 21, 1937) is an American actress and activist. Recognized as a film icon,[3] Fonda is the recipient of various accolades, including two Academy Awards, two British Academy Film Awards, seven Golden Globe Awards, a Primetime Emmy Award, the AFI Life Achievement Award, the Honorary Palme d'Or, and the Cecil B. DeMille Award.[4]

Jane Fonda | |

|---|---|

Fonda in 2015 | |

| Born | Jane Seymour Fonda December 21, 1937 New York City, U.S. |

| Other names | Jane S. Plemiannikov[1] |

| Education | |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1959–present |

| Works | Full list |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | |

| Partner | Richard Perry (2009–2017) |

| Children | 3, including Troy Garity and Mary Williams (de facto adopted) |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Website | janefonda |

Born to socialite Frances Ford Seymour and actor Henry Fonda, Fonda made her acting debut with the 1960 Broadway play There Was a Little Girl, for which she received a nomination for the Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Play, and made her screen debut later the same year with the romantic comedy Tall Story. She rose to prominence during the 1960s with the comedies Period of Adjustment (1962), Sunday in New York (1963), Cat Ballou (1965), Barefoot in the Park (1967), and Barbarella (1968) before receiving her first Oscar nomination for They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969). Fonda then established herself as one of the most acclaimed actresses of her generation, winning the Academy Award for Best Actress twice in the '70s, for Klute (1971) and Coming Home (1978). Her other nominations are for Julia (1977), The China Syndrome (1979), On Golden Pond (1981), and The Morning After (1986). Consecutive hits Fun with Dick and Jane (1977), California Suite (1978), The Electric Horseman (1979), and 9 to 5 (1980) sustained Fonda's box-office drawing power, and she won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Actress in a Limited Series or Movie for the television film The Dollmaker (1984).

In 1982, Fonda released her first exercise video, Jane Fonda's Workout, which became the highest-selling videotape of its time.[5] It was the first of 22 such videos over the next 13 years, which collectively sold over 17 million copies. After starring in Stanley & Iris (1990), Fonda took a hiatus from acting and returned with the comedy Monster-in-Law (2005). She also returned to Broadway in the play 33 Variations (2009), earning a Tony Award for Best Actress in a Play nomination. She has since starred in the independent films Youth (2015) and Our Souls at Night (2017) and on Netflix's comedy series Grace and Frankie (2015–2022), for which she earned a nomination for the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series.

Fonda was a political activist in the counterculture era during the Vietnam War. She was photographed sitting on a North Vietnamese anti-aircraft gun on a 1972 visit to Hanoi, during which she gained the nickname "Hanoi Jane". During this time, she was effectively blacklisted in Hollywood. She has also protested the Iraq War and violence against women and describes herself as a feminist and environmental activist.[6] In 2005, along with Robin Morgan and Gloria Steinem, she cofounded the Women's Media Center, an organization that works to amplify the voices of women in the media through advocacy, media and leadership training, and the creation of original content. Fonda serves on the board of the organization. Based in Los Angeles, she has lived all over the world, including six years in France and 20 in Atlanta.

Early life and education

Jane Seymour Fonda was born via caesarean section on December 21, 1937, at Doctors Hospital in New York City.[7][8] Her parents were Canadian-born socialite Frances Ford Seymour and American actor Henry Fonda. According to her father, the surname Fonda came from an Italian ancestor who immigrated to the Netherlands in the 1500s.[9] There, he intermarried; the resultant family began to use Dutch given names, with Jane's first Fonda ancestor reaching New York in 1650.[10][11][12] Fonda also has English, French, and Scottish ancestry. She was named for the third wife of Henry VIII, Jane Seymour, to whom she is distantly related on her mother's side,[13] and because of whom, until she was in fourth grade, Fonda said she was called "Lady" (as in Lady Jane).[14] Her brother, Peter Fonda, was also an actor, and her maternal half-sister is Frances de Villers Brokaw (also known as "Pan"), whose daughter is Pilar Corrias, the owner of the Pilar Corrias Gallery in London.[15]

In 1950, when Fonda was 12, her mother committed suicide while undergoing treatment at Craig House psychiatric hospital in Beacon, New York.[16][17] Later that year, Henry Fonda married socialite Susan Blanchard, 23 years his junior; this marriage ended in divorce. Aged 15, Jane taught dance at Fire Island Pines, New York.[18]

Fonda attended Greenwich Academy in Greenwich, Connecticut; the Emma Willard School in Troy, New York; and Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York.[19] Before her acting career, she was a model and appeared twice on the cover of Vogue.[20]

Fonda became interested in the arts in 1954, while appearing with her father in a charity performance of The Country Girl at the Omaha Community Playhouse.[20] After dropping out of Vassar, she went to Paris for six months to study art.[21] Upon returning to the US, in 1958, she met Lee Strasberg; the meeting changed the course of her life. Fonda said, "I went to the Actors Studio and Lee Strasberg told me I had talent. Real talent. It was the first time that anyone, except my father – who had to say so – told me I was good. At anything. It was a turning point in my life. I went to bed thinking about acting. I woke up thinking about acting. It was like the roof had come off my life!"[22]

Career

1960s

Fonda's stage work in the late 1950s laid the foundation for her film career in the 1960s. She averaged almost two movies a year throughout the decade, starting in 1960 with Tall Story, in which she recreated one of her Broadway roles as a college cheerleader pursuing a basketball star, played by Anthony Perkins. Period of Adjustment and Walk on the Wild Side followed in 1962. In Walk on the Wild Side, Fonda played a prostitute, and earned a Golden Globe for Most Promising Newcomer. In 1963, she starred in Sunday in New York. Newsday called her "the loveliest and most gifted of all our new young actresses".[23] However, she also had detractors – in the same year, the Harvard Lampoon named her the "Year's Worst Actress" for The Chapman Report.[24] Her next two pictures, Joy House and Circle of Love (both 1964), were made in France; with the latter, Fonda became one of the first American film stars to appear nude in a foreign movie.[25] She was offered the coveted role of Lara in Doctor Zhivago, but turned it down because she didn't want to go on location for nine months.[26]

Fonda's career breakthrough came with Cat Ballou (1965), in which she played a schoolmarm-turned-outlaw. This comedy Western received five Oscar nominations, with Lee Marvin winning best actor, and was one of the year's top ten films at the box office. It was considered by many to have been the film that brought Fonda to bankable stardom. The following year, she had a starring role in The Chase opposite Robert Redford, in their first film together, and two-time Oscar winner Marlon Brando. The film received some positive reviews, but Fonda's performance was noticed by Variety magazine: "Jane Fonda, as Redford's wife and the mistress of wealthy oilman James Fox, makes the most of the biggest female role."[27] She returned to France to make The Game Is Over (1966), often described as her sexiest film, and appeared in the August 1966 issue of Playboy, in paparazzi shots taken on the set.[28] Fonda immediately sued the magazine for publishing them without her consent.[29] After this came the comedies Any Wednesday (1966), opposite Jason Robards and Dean Jones, and Barefoot in the Park (1967), again co-starring Redford.

In 1968, she played the title role in the science fiction spoof Barbarella, which established her status as a sex symbol. In contrast, the tragedy They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) won her critical acclaim and marked a significant turning point in her career; Variety wrote, "Fonda, as the unremittingly cynical loser, the tough and bruised babe of the Dust Bowl, gives a dramatic performance that gives the film a personal focus and an emotionally gripping power."[30] In addition, renowned film critic Pauline Kael, in her New Yorker review of the film, noted of Fonda: "[She] has been a charming, witty nudie cutie in recent years and now gets a chance at an archetypal character. Fonda goes all the way with it, as screen actresses rarely do once they become stars. She doesn't try to save some ladylike part of herself, the way even a good actress like Audrey Hepburn does, peeping at us from behind 'vulgar' roles to assure us she's not really like that. Fonda stands a good chance of personifying American tensions and dominating our movies in the seventies as Bette Davis did in the thirties."[31] For her performance, she won the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress and earned her first Academy Awards nomination for Best Actress. Fonda was very selective by the end of the decade, turning down lead roles in Rosemary's Baby and Bonnie and Clyde.[32]

1970s

In the seventies, Fonda enjoyed her most critically acclaimed period as an actress despite some setbacks for her ongoing activism. According to writer and critic Hilton Als, her performances starting with They Shoot Horses, Don't They? heralded a new kind of acting: for the first time, she was willing to alienate viewers, rather than try to win them over. Fonda's ability to continue to develop her talent is what sets her apart from many other performers of her generation.[31]

Fonda won her first Academy Award for Best Actress in 1971, playing a high priced call girl, the gamine Bree Daniels, in Alan J. Pakula's murder mystery Klute. Prior to shooting, Fonda spent time interviewing several prostitutes and madams. Years later, Fonda discovered that "there was like a marriage, a melding of souls between this character and me, this woman that I didn't think I could play because I didn't think I was call girl material. It didn't matter."[33] Upon its release, Klute was both a critical and commercial success, and Fonda's performance earned her widespread recognition. Pauline Kael wrote:

"As an actress, [Fonda] has a special kind of smartness that takes the form of speed; she's always a little ahead of everybody, and this quicker beat – this quicker responsiveness – makes her more exciting to watch. This quality works to great advantage in her full-scale, definitive portrait of a call girl in Klute. It's a good, big role for her, and she disappears into Bree, the call girl, so totally that her performance is very pure – unadorned by "acting". She never stands outside Bree, she gives herself over to the role, and yet she isn't lost in it—she's fully in control, and her means are extraordinarily economical. She has somehow got to a plane of acting at which even the closest closeup never reveals a false thought and, seen on the movie streets a block away, she's Bree, not Jane Fonda, walking toward us. There isn't another young dramatic actress in American films who can touch her".[34]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times also praised Fonda's performance, even suggesting that the film should have been titled Bree after her character: "What is it about Jane Fonda that makes her such a fascinating actress to watch? She has a sort of nervous intensity that keeps her so firmly locked into a film character that the character actually seems distracted by things that come up in the movie."[35] During the 1971–1972 awards season, Fonda dominated the Best Actress category at almost every major awards ceremony; in addition to her Oscar win, she received her first Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Motion Picture - Drama, her first National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Actress and her second New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress.

Between Klute in 1971 and Fun With Dick and Jane in 1977, Fonda did not have a major film success. She appeared in A Doll's House (1973), Steelyard Blues and The Blue Bird (1976). In the former, some critics felt Fonda was miscast, but her work as Nora Helmer drew praise, and a review in The New York Times opined, "Though the Losey film is ferociously flawed, I recommend it for Jane Fonda's performance. Beforehand, it seemed fair to wonder if she could personify someone from the past; her voice, inflections, and ways of moving have always seemed totally contemporary. But once again she proves herself to be one of our finest actresses, and she's at home in the 1870s, a creature of that period as much as of ours."[36] From comments ascribed to her in interviews, some have inferred that she personally blamed the situation on anger at her outspoken political views: "I can't say I was blacklisted, but I was greylisted."[37] However, in her 2005 autobiography, My Life So Far, she rejected such simplification. "The suggestion is that because of my actions against the war my career had been destroyed ... But the truth is that my career, far from being destroyed after the war, flourished with a vigor it had not previously enjoyed."[38] She reduced acting because of her political activism providing a new focus in her life. Her return to acting in a series of 'issue-driven' films reflected this new focus.

Jane Fonda did an extraordinary job with her part. She is a splendid actress with a strong analytical mind which sometimes gets in her way, and with an incredible technique and control of emotion; she can cry at will, on cue, mere drops or buckets, as the scene demands ... I thought Jane well deserved the Oscar she should have got.[39]

—Fred Zinnemann

director of Julia (1977)

In 1972, Fonda starred as a reporter alongside Yves Montand in Tout Va Bien, directed by Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin. The two directors then made Letter to Jane, in which the two spent nearly an hour discussing a news photograph of Fonda. At the time, while in Rome, she joined a feminist march on March 8 and gave a brief speech of support for the Italian women's rights.[40]

Through her production company, IPC Films, she produced films that helped return her to star status. The 1977 comedy film Fun With Dick and Jane is generally considered her "comeback" picture. Critical reaction was mixed, but Fonda's comic performance was praised; Vincent Canby of The New York Times remarked, "I never have trouble remembering that Miss Fonda is a fine dramatic actress but I'm surprised all over again every time I see her do comedy with the mixture of comic intelligence and abandon she shows here."[41] Also in 1977, she portrayed the playwright Lillian Hellman in Julia, receiving positive reviews from critics. Gary Arnold of The Washington Post described her performance as "edgy, persuasive and intriguingly tensed-up," commenting further, "Irritable, intent and agonizingly self-conscious, Fonda suggests the internal conflicts gnawing at a talented woman who craves the self-assurance, resolve and wisdom she sees in figures like Julia and Hammett."[42] For her performance, Fonda won her first BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role, her second Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama, and received her third Best Actress Oscar nomination.[43]

During this period, Fonda announced that she would make only films that focused on important issues, and she generally stuck to her word. She turned down An Unmarried Woman because she felt the part was not relevant. In 1978, Fonda was at a career peak after she won her second Best Actress Oscar for her role as Sally Hyde, a conflicted adulteress in Coming Home, the story of a disabled Vietnam War veteran's difficulty in re-entering civilian life.[43] Upon its release, the film was a popular success with audiences, and generally received good reviews; Ebert noted that her Sally Hyde was "the kind of character you somehow wouldn't expect the outspoken, intelligent Fonda to play," and Jonathan Rosenbaum of the San Diego Reader felt that Fonda was "a marvel to watch; what fascinates and involves me in her performance are the conscientious effort and thought that seem to go into every line reading and gesture, as if the question of what a captain's wife and former cheerleader was like became a source of endless curiosity and discovery for her."[44] Her performance also earned her a third Golden Globe Award for Best Actress as well, making this her second consecutive win. Also in 1978, she reunited with Alan J. Pakula to star in his post-modern Western drama Comes a Horseman as a hard-bitten rancher, and later took on a supporting role in California Suite, where she played a Manhattan workaholic and divorcee. Variety noted that she "demonstrates yet another aspect of her amazing range"[45] and Time Out New York remarked that she gave "another performance of unnerving sureness".[46]

She won her second BAFTA Award for Best Actress in 1979 with The China Syndrome, about a cover-up of a vulnerability in a nuclear power plant. Cast alongside Jack Lemmon and Michael Douglas, in one of his early roles, Fonda played a clever, ambitious television news reporter. Vincent Canby, writing for The New York Times, singled out Fonda's performance for praise: "The three stars are splendid, but maybe Miss Fonda is just a bit more than that. Her performance is not that of an actress in a star's role, but that of an actress creating a character that happens to be major within the film. She keeps getting better and better."[47] This role also earned her Oscar and Golden Globe nominations for Best Actress. The same year, she starred in the western adventure-romance film The Electric Horseman with her frequent co-star, Robert Redford. Although the film received mixed reviews, The Electric Horseman was a box office success, becoming the eleventh highest-grossing film of 1979[48] after grossing a domestic total of nearly $62 million.[49] By the late 1970s, Motion Picture Herald ranked Fonda, as Hollywood's most bankable actress.[50]

1980s

In 1980, Fonda starred in 9 to 5 with Lily Tomlin and Dolly Parton. The film was a huge critical and box office success, becoming the second highest-grossing release of the year.[51] Fonda had long wanted to work with her father, hoping it would help their strained relationship.[43] She achieved this goal when she purchased the screen rights to the play On Golden Pond, specifically for her father and her.[52] The father-daughter rift depicted on screen closely paralleled the real-life relationship between the two Fondas; they eventually became the first father-daughter duo to earn Oscar nominations (Jane earned her first Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination) for their roles in the same film. On Golden Pond, which also starred four-time Oscar winner Katharine Hepburn, brought Henry Fonda his only Academy Award for Best Actor, which Jane accepted on his behalf, as he was ill and could not leave home. He died five months later.[43] Both films grossed over $100 million domestically.[53][54]

Fonda continued to appear in feature films throughout the 1980s, winning an Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress for her portrayal of a Kentucky mountain woman in The Dollmaker (1984), and starring in the role of Dr. Martha Livingston in Agnes of God (1985). The following year, she played an alcoholic actress and murder suspect in the 1986 thriller The Morning After, opposite Jeff Bridges. In preparation for her role, Fonda modelled the character on the starlet Gail Russell, who, at 36, was found dead in her apartment, among empty liquor bottles. Writing for The New Yorker, Pauline Kael commended Fonda for giving "a raucous-voiced, down-in-the-dirty performance that has some of the charge of her Bree in Klute, back in 1971".[55] For her performance, she was nominated for yet another Academy Award for Best Actress. She ended the decade by appearing in Old Gringo.

For many years Fonda took ballet class to keep fit, but after fracturing her foot while filming The China Syndrome, she was no longer able to participate. To compensate, she began participating in aerobics and strengthening exercises under the direction of Leni Cazden. The Leni Workout became the Jane Fonda Workout, which began a second career for her, continuing for many years.[43] This was considered one of the influences that started the fitness craze among baby boomers, then approaching middle age. In 1982, Fonda released her first exercise video, titled Jane Fonda's Workout, inspired by her best-selling book, Jane Fonda's Workout Book. Jane Fonda's Workout became the highest selling home video of the next few years, selling over a million copies. The video's release led many people to buy the then-new VCR in order to watch and perform the workout at home.[56] The exercise videos were directed by Sidney Galanty, who produced the first video and 11 more after that. She would subsequently release 23 workout videos with the series selling a total of 17 million copies combined, more than any other exercise series.[43] She released five workout books and thirteen audio programs, through 1995. After a fifteen-year hiatus, she released two new fitness videos on DVD in 2010, aiming at an older audience.[3]

On May 3, 1983, she had entered into a non-exclusive agreement with movie production distributor Columbia Pictures, whereas she would star in and/or produce projects under her own banner Jayne Development Corporation, and she would develop offices at The Burbank Studios, and the company immediately started after her previous office she co-founded with Bruce Gilbert, IPC Films shuttered down.[57] On June 25, 1985, she renamed her production company, Fonda Films, because the original name felt that it would sound like a real estate company.[58]

1990s

In 1990, she starred in the romantic drama Stanley & Iris (1990) with Robert De Niro, which was her last film for 15 years. The film did not fare well at the box office. Despite receiving mixed to negative reviews, Fonda's performance as the widowed Iris was praised by Vincent Canby, who stated, "Fonda's increasingly rich resources as an actress are evident in abundance here. They even overcome one's awareness that just beneath Iris's frumpy clothes, there is a firm, perfectly molded body that has become a multi-million-dollar industry."[59] In 1991, after three decades in film, Fonda announced her retirement from the film industry.[60]

2000s

In 2005, she returned to the screen with the box office success Monster-in-Law, starring opposite Jennifer Lopez.[43] Two years later, Fonda starred in the Garry Marshall-directed drama Georgia Rule alongside Felicity Huffman and Lindsay Lohan. Georgia Rule was panned by critics, but A. O. Scott of The New York Times felt the film belonged to Fonda and co-star Lohan, before writing, "Ms. Fonda's straight back and piercing eyes, the righteous jaw line she inherited from her father and a reputation for humorlessness all serve her well here, but it is her warmth and comic timing that make Georgia more than a provincial scold."[61]

In 2009, Fonda returned to Broadway for the first time since 1963, playing Katherine Brandt in Moisés Kaufman's 33 Variations.[62][63] In a mixed review, Ben Brantley of The New York Times praised Fonda's "layered crispness" and her "aura of beleaguered briskness that flirts poignantly with the ghost of her spiky, confrontational screen presence as a young woman. For those who grew up enthralled with Ms. Fonda's screen image, it's hard not to respond to her performance here, on some level, as a personal memento mori."[64] The role earned her a Tony nomination for Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Play.[65]

2010s

Fonda played a leading role in the 2011 drama All Together, which was her first film in French since Tout Va Bien in 1972.[66][67][68] The same year she starred alongside Catherine Keener in Peace, Love and Misunderstanding, playing a hippie grandmother.[69] In 2012, Fonda began a recurring role as Leona Lansing, CEO of a major media company, in HBO's original political drama The Newsroom. Her role continued throughout the show's three seasons, and Fonda received two Emmy nominations for Outstanding Guest Actress in a Drama Series.

In 2013, Fonda had a small role in The Butler, portraying First Lady Nancy Reagan. She had more film work the following year, appearing in the comedies Better Living Through Chemistry and This is Where I Leave You. She voiced Maxine Lombard in the season 26 episode "Opposites A-Frack". a character on The Simpsons.[70] She played an acting diva in Paolo Sorrentino's Youth in 2015, for which she earned a Golden Globe Award nomination. She also appeared in Fathers and Daughters (2015) with Russell Crowe.

Fonda appeared as the co-lead in the Netflix series Grace and Frankie. She and Lily Tomlin played aging women whose husbands reveal they are in love with one another. Filming on the first season was completed in November 2014,[71] and the show premiered online on May 8, 2015. The series concluded in 2022 after running for 7 seasons.[72]

In 2016, Fonda voiced Shuriki in Elena and the Secret of Avalor. In June 2016, the Human Rights Campaign released a video in tribute to the victims of the Orlando nightclub shooting; in the video, Fonda and others told the stories of the people killed there.[73][74]

Fonda starred in her fourth collaboration with Robert Redford in the 2017 romantic drama film Our Souls at Night. The film and Fonda's performance received critical acclaim upon release. In 2018, she starred opposite Diane Keaton, Mary Steenburgen, and Candice Bergen in the romantic comedy film Book Club. Although opened to mixed reviews, the film was a major box office success grossing $93.4 million against a $10 million budget, despite releasing the same day as Deadpool 2. Fonda is the subject of an HBO original documentary entitled Jane Fonda in Five Acts, directed by the documentarian Susan Lacy. Receiving rave reviews, it covers Fonda's life from childhood through her acting career and political activism and then to the present day.[75] It premiered on HBO on September 24, 2018.[76]

2020s

Fonda filmed the seventh and final season of Grace and Frankie in 2021, finishing production in November. The first four episodes premiered August 14, 2021,[77] with the final 12 released on Netflix on April 29, 2022. In November 2021, it was announced Fonda would be in the second installment of Amazon Prime Video's Yearly Departed. She appeared alongside the host Yvonne Orji, and fellow eulogy givers Chelsea Peretti, Megan Stalter, Dulcé Sloan, Aparna Nancherla, and X Mayo. It premiered on December 23, 2021.[78]

Fonda joined the cast of the 2023 film 80 for Brady, which pairs her with veteran actresses Lily Tomlin, Rita Moreno, and Sally Field. It also stars former NFL Quarterback, Tom Brady. She and Tomlin headline Paul Weitz's black comedy Moving On, co-starring Malcolm McDowell and Richard Roundtree. Her third project for 2023 is Book Club: The Next Chapter, which she made in Italy.

Other activities

Political activism

During the 1960s, Fonda engaged in political activism in support of the Civil Rights Movement, and in opposition to the Vietnam War.[43] Fonda's visits to France brought her into contact with leftist French intellectuals who were opposed to war, an experience that she later characterized as "small-c communism".[79] Along with other celebrities, she supported the Alcatraz Island occupation by American Indians in 1969, which was intended to call attention to the failures of the government with regard to treaty rights and the movement for greater Indian sovereignty.[80]

She supported Huey Newton and the Black Panthers in the early 1970s, stating: "Revolution is an act of love; we are the children of revolution, born to be rebels. It runs in our blood." She called the Black Panthers "our revolutionary vanguard ... we must support them with love, money, propaganda and risk."[81] She has been involved in the feminist movement since the 1970s and dovetails her activism in support of civil rights.

Opposition to the Vietnam War

On May 4, 1970, Fonda appeared before an assembly at the University of New Mexico, in Albuquerque, to speak on G.I. rights and issues. The end of her presentation was met with a discomfiting silence until Beat poet Gregory Corso staggered onto the stage, drunk. He challenged Fonda, using a four-letter expletive: why hadn't she addressed the shooting of four students at Kent State by the Ohio National Guard, which had just taken place? In her autobiography, Fonda revisited the incident: "I was shocked by the news and felt like a fool." On the same day, she joined a protest march on the home of university president Ferrel Heady. The protesters called themselves "They Shoot Students, Don't They?" – a reference to Fonda's recently released film, They Shoot Horses, Don't They?, which had just been screened in Albuquerque.[21]

In the same year, Fonda spoke out against the war at a rally organized by Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. She offered to help raise funds for VVAW and was rewarded with the title of Honorary National Coordinator.[82] That fall, Fonda started a tour of college campuses on which she raised funds for the organization. As noted by The New York Times, Fonda was a "major patron" of the VVAW.[83]

In 1971, Fonda, with Fred Gardner and Donald Sutherland formed the FTA tour ("Free The Army", a play on the troop expression "Fuck The Army"), an anti-war road show designed as an answer to Bob Hope's USO tour. The tour, described as "political vaudeville" by Fonda, visited military towns along the West Coast, aiming to establish a dialogue with soldiers about their upcoming deployments to Vietnam. The dialogue was made into a movie (F.T.A.) which contained strong, frank criticism of the war by servicemembers; it was released in 1972.[84]

Visit to Hanoi

Between 1965 and 1972, almost 300 Americans – mostly civil rights activists, teachers, and pastors – traveled to North Vietnam to see firsthand the war situation with the Vietnamese. News media in the United States predominantly provided a U.S. viewpoint, and American travelers to North Vietnam were routinely harassed upon their return home.[85] Fonda also visited Vietnam, traveling to Hanoi in July 1972 to witness firsthand the bombing damage to the dikes. After touring and photographing dike systems in North Vietnam, she said the United States had been intentionally targeting the dike system along the Red River. Columnist Joseph Kraft, who was also touring North Vietnam, said he believed the damage to the dikes was incidental and was being used as propaganda by Hanoi, and that, if the U.S. Air Force were "truly going after the dikes, it would do so in a methodical, not a harum-scarum way".[86] Sweden's ambassador to Vietnam, however, observed the bomb damage to the dikes and described it as "methodic". Other journalists reported that the attacks were "aimed at the whole system of dikes".[85]

Fonda was photographed seated on a North Vietnamese anti-aircraft gun; the photo outraged a number of Americans,[87] and earned her the nickname "Hanoi Jane".[88][89] In her 2005 autobiography, she wrote that she was manipulated into sitting on the battery; she had been horrified at the implications of the pictures. In a 2011 entry at her official website, Fonda explained:

It happened on my last day in Hanoi. I was exhausted and an emotional wreck after the 2-week visit ... The translator told me that the soldiers wanted to sing me a song. He translated as they sung. It was a song about the day 'Uncle Ho' declared their country's independence in Hanoi's Ba Dinh Square. I heard these words: 'All men are created equal; they are given certain rights; among these are life, Liberty and Happiness.' These are the words Ho pronounced at the historic ceremony. I began to cry and clap. 'These young men should not be our enemy. They celebrate the same words Americans do.' The soldiers asked me to sing for them in return ... I memorized a song called 'Dậy mà đi' ["Get up and go"], written by anti-war South Vietnamese students. I knew I was slaughtering it, but everyone seemed delighted that I was making the attempt. I finished. Everyone was laughing and clapping, including me ... Here is my best, honest recollection of what happened: someone (I don't remember who) led me towards the gun, and I sat down, still laughing, still applauding. It all had nothing to do with where I was sitting. I hardly even thought about where I was sitting. The cameras flashed ... It is possible that it was a set up, that the Vietnamese had it all planned. I will never know. But if they did I can't blame them. The buck stops here. If I was used, I allowed it to happen ... a two-minute lapse of sanity that will haunt me forever ... But the photo exists, delivering its message regardless of what I was doing or feeling. I carry this heavy in my heart. I have apologized numerous times for any pain I may have caused servicemen and their families because of this photograph. It was never my intention to cause harm.[90]

Fonda made radio broadcasts on Hanoi Radio throughout her two-week tour, describing her visits to villages, hospitals, schools, and factories that had been bombed, and denouncing U.S. military policy.[91][92] During the course of her visit, Fonda visited American prisoners of war (POWs), and brought back messages from them to their families. When stories of torture of returning POWs were later being publicized by the Nixon administration, Fonda said that those making such claims were "hypocrites and liars and pawns", adding about the prisoners she visited, "These were not men who had been tortured. These were not men who had been starved. These were not men who had been brainwashed."[93] In addition, Fonda told The New York Times in 1973, "I'm quite sure that there were incidents of torture ... but the pilots who were saying it was the policy of the Vietnamese and that it was systematic, I believe that's a lie."[94] Her visits to the POW camp led to persistent and exaggerated rumors which were repeated widely, and continued to circulate on the Internet decades later. Fonda, as well as the named POWs, have denied the rumors,[90] and subsequent interviews with the POWs showed these allegations to be false—the persons named had never met Fonda.[92]

In 1972, Fonda helped fund and organize the Indochina Peace Campaign, which[95] continued to mobilize antiwar activists in the US after the 1973 Paris Peace Agreement, until 1975 when the United States withdrew from Vietnam.[96]

Because of her tour of North Vietnam during wartime and the subsequent rumors, resentment against her persists among some veterans and serving U.S. military. For example, when a U.S. Naval Academy plebe ritually shouted out "Goodnight, Jane Fonda!", the entire company of midshipmen plebes replied "Goodnight, bitch!"[97][98] This practice has since been prohibited by the academy's Plebe Summer Standard Operating Procedures.[99] In 2005, Michael A. Smith, a U.S. Navy veteran, was arrested for disorderly conduct in Kansas City, Missouri, after he spat chewing tobacco in Fonda's face during a book-signing event for her autobiography, My Life So Far. He told reporters that he "consider[ed] it a debt of honor", adding "she spit in our faces for 37 years. It was absolutely worth it. There are a lot of veterans who would love to do what I did." Fonda refused to press charges.[100][101]

Regrets

In a 1988 interview with Barbara Walters, Fonda expressed regret for some of her comments and actions, stating:

I would like to say something, not just to Vietnam veterans in New England, but to men who were in Vietnam, who I hurt, or whose pain I caused to deepen because of things that I said or did. I was trying to help end the killing and the war, but there were times when I was thoughtless and careless about it and I'm very sorry that I hurt them. And I want to apologize to them and their families. ... I will go to my grave regretting the photograph of me in an anti-aircraft gun, which looks like I was trying to shoot at American planes. It hurt so many soldiers. It galvanized such hostility. It was the most horrible thing I could possibly have done. It was just thoughtless.[102]

In a 60 Minutes interview on March 31, 2005, Fonda reiterated that she had no regrets about her trip to North Vietnam in 1972, with the exception of the anti-aircraft-gun photo. She stated that the incident was a "betrayal" of American forces and of the "country that gave me privilege". Fonda said, "The image of Jane Fonda, Barbarella, Henry Fonda's daughter ... sitting on an enemy aircraft gun was a betrayal ... the largest lapse of judgment that I can even imagine." She later distinguished between regret over the use of her image as propaganda and pride for her anti-war activism: "There are hundreds of American delegations that had met with the POWs. Both sides were using the POWs for propaganda ... It's not something that I will apologize for." Fonda said she had no regrets about the broadcasts she made on Radio Hanoi, something she asked the North Vietnamese to do: "Our government was lying to us and men were dying because of it, and I felt I had to do anything that I could to expose the lies and help end the war."[103]

Subject of government surveillance

In 2013, it was revealed that Fonda was one of approximately 1,600 Americans whose communications between 1967 and 1973 were monitored by the United States National Security Agency (NSA) as part of Project MINARET, a program that some NSA officials have described as "disreputable if not downright illegal".[104][105] Fonda's communications, as well as those of her husband, Tom Hayden, were intercepted by Britain's Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). Under the UKUSA Agreement, intercepted data on Americans were sent to the U.S. government.[106][107]

1970 arrest

On November 2, 1970, Fonda was arrested by authorities at Cleveland Hopkins International Airport on suspicion of drug trafficking.[108] Her luggage was searched when she re-entered the United States after participating in an anti-war college speaking tour in Canada, and several small baggies containing pills were seized.[109] Although Fonda protested that the pills were harmless vitamins, she was booked by police and then released on bond. Fonda alleged that the arresting officer told her he was acting on direct orders from the Nixon White House.[110] As she wrote in 2009, "I told them what [the vitamins] were but they said they were getting orders from the White House. I think they hoped this 'scandal' would cause the college speeches to be canceled and ruin my respectability."[108] After lab tests confirmed the pills were vitamins, the charges were dropped with little media attention.

Fonda's mugshot from the arrest, in which she raises her fist in a sign of solidarity, has since become a widely published image of the actress.[109] It was used as the poster image for the 2018 HBO documentary on Fonda, "Jane Fonda in Five Acts", with a giant billboard sporting the image erected in Times Square in September 2018.[111] In 2017, she began selling merchandise with her mugshot image to benefit the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Power & Potential.[109]

Feminist causes

In a 2017 interview with Brie Larson, published by People magazine, Fonda stated, "One of the great things the women's movement has done is to make us realise that (rape and abuse is) not our fault. We were violated and it's not right." She said, "I've been raped, I've been sexually abused as a child and I've been fired because I wouldn't sleep with my boss." She said, "I always thought it was my fault; that I didn't do or say the right thing. I know young girls who've been raped and didn't even know it was rape. They think, 'It must have been because I said 'no' the wrong way.'"

Through her work, Fonda said she wants to help abuse victims "realize that [rape and abuse] is not our fault". Fonda said that her difficult past led her to become such a passionate activist for women's rights. The actress is an active supporter of the V-Day movement, which works to stop violence against women and girls. In 2001, she established the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health, which aims to help prevent teen pregnancy. She said she was "brought up with the disease to please" in her early life.[112] Fonda revealed in 2014 that her mother, Frances Ford Seymour, was recurrently sexually abused as young as eight, and this may have led to her suicide when Jane was 12.[113]

Fonda has been a longtime supporter of feminist causes, including V-Day, of which she is an honorary chairperson, a movement to stop violence against women, inspired by the off-Broadway hit The Vagina Monologues. She was at the first summit in 2002, bringing together founder Eve Ensler, Afghan women oppressed by the Taliban, and a Kenyan activist campaigning to save girls from genital mutilation.[114]

In 2001, she established the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health at Emory University in Atlanta to help prevent adolescent pregnancy through training and program development.[115]

On February 16, 2004, Fonda led a march through Ciudad Juárez, with Sally Field, Eve Ensler and other women, urging Mexico to provide sufficient resources to newly appointed officials in helping investigate the murders of hundreds of women in the rough border city.[116] In 2004, she also served as a mentor to the first all-transgender cast of The Vagina Monologues.[117]

In the days before the September 17, 2006, Swedish elections, Fonda went to Sweden to support the new political party Feministiskt initiativ in their election campaign.[118]

In My Life So Far, Fonda stated that she considers patriarchy to be harmful to men as well as women. She also states that for many years, she feared to call herself a feminist, because she believed that all feminists were "anti-male". But now, with her increased understanding of patriarchy, she feels that feminism is beneficial to both men and women, and states that she "still loves men", adding that when she divorced Ted Turner, she felt like she had also divorced the world of patriarchy, and was very happy to have done so.[119]

In April 2016, Fonda said that while she was 'glad' that Bernie Sanders was running, she predicted Hillary Clinton would become the first female president, whose supposed win Fonda believed would result in a "violent backlash" but Clinton did not become president and got defeated by Republican Party's nominee businessman Donald Trump in the general election later that year. Fonda went on to say that we need to "help men understand why they are so threatened – and change the way we view masculinity".[120] In March 2020, Fonda later endorsed Sanders for the Democratic nomination in the 2020 election, calling him the "climate candidate".[121]

LGBTQ+ support

Fonda has publicly shown her support of the LGBTQ+ community many times throughout her career. In August 2021, Fonda, the cast of Grace and Frankie, and other advocates joined to support a fundraiser hosted by the Los Angeles LGBT Center to help members of the LGBTQ+ community during the COVID-19 pandemic.[122]

Fonda spoke out as an LGBTQ+ ally long before it was common.[123] She appeared in a video of a 1979 interview during the White Night Riots in San Francisco after the assassination of Harvey Milk, the first openly gay politician in California. During the interview she was asked if the gay community was still being discriminated against, to which she replied that they "are culturally, psychologically, economically, politically" being discriminated against.[124] Fonda was then asked if the gay community has used her as an advocate and she replied that she hopes they will use her, though she stressed that "they are a very powerful movement, they don't need me, but they like me (and) they know by working together we can be stronger than either entity is by itself."[124]

Native Americans

Fonda went to Seattle, in 1970 to support a group of Native Americans who were led by Bernie Whitebear. The group had occupied part of the grounds of Fort Lawton, which was in the process of being surplussed by the United States Army and turned into a park. The group was attempting to secure a land base where they could establish services for the sizable local urban Indian population, protesting that "Indians had a right to part of the land that was originally all theirs."[125] The endeavor succeeded and the Daybreak Star Cultural Center was constructed in the city's Discovery Park.[126]

In addition to environmental reasons, Fonda has been a critic of oil pipelines because of their being built without consent on Native American tribal land. In 2017, Fonda responded to American President Donald Trump's mandate to resume construction of the controversial North Dakota Pipelines by saying that Trump "does this illegally because he has not gotten consent from the tribes through whose countries this goes" and pointing out that "the U.S. has agreed to treaties that require them to get the consent of the people who are affected, the indigenous people who live there."[127]

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

In December 2002, Fonda visited Israel and the West Bank as part of a tour focusing on stopping violence against women. She demonstrated with Women in Black against Israel's occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip outside the residence of Israel's Prime Minister. She later visited Jewish and Arab doctors, and patients at a Jerusalem hospital, followed by visits to Ramallah to see a physical rehabilitation center and Palestinian refugee camp.[128]

In September 2009, she was one of more than 1,500 signatories to a letter protesting the 2009 Toronto International Film Festival's spotlight on Tel Aviv.[129] The protest letter said that the spotlight on Tel Aviv was part of "the Israeli propaganda machine" because it was supported in part by funding from the Israeli government and had been described by the Israeli Consul General Amir Gissin as being part of a Brand Israel campaign intended to draw attention away from Israel's conflict with the Palestinians.[130][131][132] Other signers included actor Danny Glover, musician David Byrne, journalist John Pilger, and authors Alice Walker, Naomi Klein, and Howard Zinn.[133][134]

Fonda, in The Huffington Post, said she regretted some of the language used in the original protest letter and how it "was perhaps too easily misunderstood. It certainly has been wildly distorted. Contrary to the lies that have been circulated, the protest letter was not demonizing Israeli films and filmmakers." She continued, writing "the greatest 're-branding' of Israel would be to celebrate that country's long standing, courageous and robust peace movement by helping to end the blockade of Gaza through negotiations with all parties to the conflict, and by stopping the expansion of West Bank settlements. That's the way to show Israel's commitment to peace, not a PR campaign. There will be no two-state solution unless this happens."[135] Fonda emphasized that she, "in no way, support[s] the destruction of Israel. I am for the two-state solution. I have been to Israel many times and love the country and its people."[135] Several prominent Atlanta Jews subsequently signed a letter to The Huffington Post rejecting the vilification of Fonda, who they described as "a strong supporter and friend of Israel".[136]

Opposition to the Iraq War

Fonda argued that the Iraq War would turn people all over the world against America, and asserted that a global hatred of America would result in more terrorist attacks in the aftermath of the war. In July 2005, Fonda announced plans to make an anti-war bus tour in March 2006 with her daughter and several families of military veterans, saying that some war veterans she had met while on her book tour had urged her to speak out against the Iraq War.[137] She later canceled the tour due to concerns that she would divert attention from Cindy Sheehan's activism.[138]

In September 2005, Fonda was scheduled to join British politician and anti-war activist George Galloway at two stops on his U.S. book tour—Chicago, and Madison, Wisconsin. She canceled her appearances at the last minute, citing instructions from her doctors to avoid travel following recent hip surgery.[139]

On January 27, 2007, Fonda participated in an anti-war rally and march held on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., declaring that "silence is no longer an option".[140] She spoke at an anti-war rally earlier that day at the Navy Memorial, where members of the organization Free Republic picketed in a counter protest.[141]

Fonda and Kerry

In the 2004 presidential election, her name was used as a disparaging epithet against John Kerry, a former VVAW leader, who was then the Democratic Party presidential candidate. Republican National Committee Chairman Ed Gillespie called Kerry a "Jane Fonda Democrat". Kerry's opponents also circulated a photograph showing Fonda and Kerry in the same large crowd at a 1970 anti-war rally, though they sat several rows apart. A faked composite photograph, which gave a false impression that the two had shared a speaker's platform, was also circulated.[142]

Environmentalism

In 2015, Fonda expressed disapproval of President Barack Obama's permitting of Arctic drilling (Petroleum exploration in the Arctic) at the Sundance Film Festival. In July, she marched in a Toronto protest called the "March for Jobs, Justice, and Climate", which was organized by dozens of nonprofits, labor unions, and environmental activists, including Canadian author Naomi Klein. The march aimed to show businesses and politicians alike that climate change is inherently linked to issues that may seem unrelated.[143]

In addition to issues of civil rights, Fonda has been an opponent of oil developments and their adverse effects on the environment. In 2017, while on a trip with Greenpeace to protest oil developments, Fonda criticized Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau saying at the summit on climate change in Paris, known as the Paris agreement, Trudeau "talked so beautifully of needing to meet the requirements of the climate treaty and to respect and hold to the treaties with indigenous people ... and yet he has betrayed every one of the things he committed to in Paris."[144]

In October 2019, Fonda was arrested three times in consecutive weeks protesting climate change outside the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. She was arrested with members of the group Oil Change International on October 11,[145][146] with Grace and Frankie co-star Sam Waterston on October 18,[147] and with actor Ted Danson on October 25.[148] On November 1, Fonda was arrested for the fourth consecutive Friday; also arrested were Catherine Keener and Rosanna Arquette.[149][150] On December 5, 2019, Fonda explained her position in a New York Times op-ed.[151]

In March 2022, Fonda launched the Jane Fonda Climate PAC, a political action committee with the purpose of ousting politicians supporting the fossil fuel industry.[152]

Writing

On April 5, 2005, Random House published Fonda's autobiography My Life So Far. The book describes her life as a series of three acts, each thirty years long, and declares that her third "act" will be her most significant, partly because of her commitment to Christianity, and that it will determine the things for which she will be remembered.[119]

Fonda's autobiography was well received by book critics and noted to be "as beguiling and as maddening as Jane Fonda herself" in its review in The Washington Post, calling her a "beautiful bundle of contradictions".[153] The New York Times called the book "achingly poignant".[154]

In January 2009, Fonda began chronicling her return to Broadway in a blog with posts about topics ranging from her Pilates class to fears and excitement about her new play. She uses Twitter and has a Facebook page.[155]

In 2011, Fonda published a new book: Prime Time: Love, health, sex, fitness, friendship, spirit – making the most of all of your life. It offers stories from her own life as well as from the lives of others, giving her perspective on how to better live what she calls "the critical years from 45 and 50, and especially from 60 and beyond".

On September 8, 2020, HarperCollins published Fonda's book, What Can I Do?: The Truth About Climate Change and How to Fix It.[156]

Philanthropy

Fonda's charitable works have focused on youth and education, adolescent reproductive health, environment, human services, and the arts.

Fonda marketed her highly successful line of exercise videos and books in order to fund the Campaign for Economic Democracy, a California lobbying organization she founded with her second husband Tom Hayden in 1978.[110]

Fonda has established the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Power and Potential (GCAPP) in the mid-1990s and the Fonda Family Foundation in the late 1990s. In the mid-2000s, Fonda founded the Jane Fonda Foundation in 2004 with one million dollars of her own money as a charitable corporation with herself as president, chair, director and secretary; Fonda contributes 10 hours each week on its behalf.[157][158][159][160] In 2017, she began selling merchandise featuring her 1970 arrest mugshot on her website, the proceeds of which benefit GCAPP.[109]

Personal life

Marriages and relationships

.jpg.webp)

Fonda writes in her autobiography that she lost her virginity at age 18 to actor James Franciscus.[161] In the late 1950s and early 1960s, she dated automobile racing manager Giovanni Volpi,[162] producers José Antonio Sainz de Vicuña[163] and Sandy Whitelaw[164] as well as actors Warren Beatty,[165] Peter Mann,[166] Christian Marquand[167] and William Wellman Jr.[168] Fonda has acknowledged that during this period, like many single women in Hollywood, she often bearded for closeted homosexuals,[169][170] including dancer Timmy Everett,[171] theater director Andreas Voutsinas[172] and actor Earl Holliman.[173][174]

Fonda and her first husband, French film director Roger Vadim, became an item in December 1963 and married on August 14, 1965, at the Dunes Hotel in Las Vegas.[175] The couple had a daughter, Vanessa Vadim, born on September 28, 1968, in Boulogne-Billancourt and named after actress and activist Vanessa Redgrave.[176] Separation reports surfaced in March 1970, which Fonda's spokesman called "totally untrue",[177] though by mid-1972 she was conceding: "We're separated. Not legally, just separated. We're friends."[178] In the early 1970s, Fonda had affairs with political organizer Fred Gardner and Klute co-star Donald Sutherland.[179][180][181]

On January 19, 1973, three days after obtaining a divorce from Vadim in Santo Domingo,[182] Fonda married activist Tom Hayden in a free-form ceremony at her home in Laurel Canyon.[183] She had become involved with Hayden the previous summer, and was three months pregnant when they married.[184] Their son, Troy O'Donovan Garity, was born on July 7, 1973, in Los Angeles and was given his paternal grandmother's maiden name, as the names "Fonda and Hayden carried too much baggage." Fonda and Hayden named their son for Nguyen Van Troi, the Viet Cong member who had attempted to assassinate US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.[185] Hayden chose O'Donovan as the middle name after Irish revolutionary Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa.[186] In 1982, Fonda and Hayden unofficially adopted an African-American teenager, Mary Luana Williams (known as Lulu),[187] whose parents were Black Panthers.[188] Fonda and Hayden separated over the Christmas holiday of 1988 and divorced on June 10, 1990, in Santa Monica.[189][190] In 1989, while estranged from Hayden, Fonda had a seven-month relationship with soccer player Lorenzo Caccialanza.[191] She was linked with actor Rob Lowe that same year.[192]

Fonda married her third husband, cable television tycoon and CNN founder Ted Turner, on December 21, 1991, at a ranch near Capps, Florida, about 20 miles east of Tallahassee.[193] The pair separated in 2000 and divorced on May 22, 2001, in Atlanta.[194][195]

Seven years of celibacy followed,[196] then from 2007 to 2008 Fonda was the companion of widowered management consultant Lynden Gillis.[197][198]

In mid-2009, Fonda began a relationship with record producer Richard Perry. It ended in January 2017.[199][200] That December, when asked what she had learned about love, Fonda told Entertainment Tonight: "Nothing. I'm not cut out for it!"[201]

In a 2018 interview, Fonda stated that up to age 62, she always felt she had to seek the validation of men in order to prove to herself that she had value as a person, something she attributes to her mother's early death leaving her without a female role model. As a consequence, she attached herself to "alpha males", some of whom reinforced her feelings of inadequacy, despite her professional success. Fonda said that she came to see that attitude as a failing of the men in her life: "Some men have a hard time realizing that the woman they're married to is strong and smart and they have to diminish that, because it makes them feel diminished. Too bad we have defined masculinity in such a way that it's so easily shamed."[202]

In 2018 she said, "I'm not dating anymore, but I did up until a couple of years ago. I'm 80; I've closed up shop down there."[203]

Faith

Fonda grew up atheist but turned to Christianity in the early 2000s. She describes her beliefs as being "outside of established religion" with a more feminist slant and views God as something that "lives within each of us as Spirit (or soul)".[204] Fonda once refused to say "Jesus Christ" in Grace and Frankie and requested a script change.[205] She practices zazen and yoga.[206][207]

Health

As a child, Fonda suffered from a poor self-image and lacked confidence in her appearance, an issue exacerbated by her father Henry Fonda. About that, Fonda said:

I was raised in the '50s. I was taught by my father [actor Henry Fonda] that how I looked was all that mattered, frankly. He was a good man, and I was mad for him, but he sent messages to me that fathers should not send: Unless you look perfect, you're not going to be loved.

In another interview with Oprah Winfrey, Fonda confessed, after years of struggling with her self-image, "It took me a long long time to realize we're not meant to be perfect, we're meant to be whole."[208]

In adulthood, Fonda developed bulimia, which took a toll on her quality of life for many years, an issue that also affected her mother Frances Ford Seymour, who died by suicide when Fonda was 12. On the subject of her recovery from bulimia, Fonda said,

It was in my 40s, and if you suffer from bulimia, the older you get, the worse it gets. It takes longer to recover from a bout ... I had a career, I was winning awards, I was supporting nonprofits, I had a family. I had to make a choice: I live or I die.[209][210]

Fonda was diagnosed with breast cancer and osteoporosis in her later years.[211] She underwent a lumpectomy in November 2010 and recovered.[212] In April 2019, Fonda revealed she had a cancerous growth removed from her lower lip the previous year and pre-melanoma growths removed from her skin.[211]

On September 2, 2022, Fonda announced that she has been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and that she had begun chemotherapy treatments, expected to last six months.[213] On December 15, 2022, Fonda stated that her cancer was in remission and that her chemotherapy would be discontinued.[214]

Filmography

Awards and honors

In 1962, Fonda was given the honorary title of "Miss Army Recruiting" by the Pentagon.[215]

In 1981, she was awarded the Women in Film Crystal Award.[216]

In 1994, the United Nations Population Fund made Fonda a Goodwill Ambassador.[217] In 2004, she was awarded the Women's eNews 21 Leaders for the 21st Century award as one of Seven Who Change Their Worlds.[218] In 2007, Fonda was awarded an Honorary Palme d'Or by Cannes Film Festival President Gilles Jacob for career achievement. Only three others had received such an award – Jeanne Moreau, Alain Resnais, and Gérard Oury.[219]

In December 2008, Fonda was inducted into the California Hall of Fame, located at The California Museum for History, Women and the Arts.[217] In November and December 2009, she received the National German Sustainability Award[220] and New York Women's Agenda Lifetime Achievement Award. She was also selected as the 42nd recipient (2014) of the AFI Life Achievement Award.[221] In 2017, she received a Goldene Kamera lifetime achievement award.[222]

She was one of fifteen women selected to appear on the cover of the September 2019 issue of British Vogue, by guest editor Meghan, Duchess of Sussex.[223]

In 2019, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame[224] and in the following year she was on the list of the BBC's 100 Women announced on November 23, 2020.[225]

In September 2023, Fonda received the John Steinbeck “In the Souls of the People” Award.[226][227]

See also

References

- Congressional Serial Set Archived April 15, 2023, at the Wayback Machine (1973). U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 103

- Davidson 1990, p. 50. "Jane was christened Jane Seymour Fonda and, as a child, was known as Lady Jane by her mother and everyone else."

- Goldwert, Lindsay (September 14, 2010). "Jane Fonda is back in her leotard, at 72; iconic actress and fitness guru to debut new fitness DVDs". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- Jane Fonda and Robert Redford Golden Lions in Venice She is part of the Fonda acting family. Archived January 15, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. labiennale.org

- "Work Out with Jane Fonda, No VHS Required". Shape Magazine. December 29, 2014. Archived from the original on November 25, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- "Interview". WNYC Radio FM. NPR. November 1, 2019.

- "Henry Fonda Is Daddy of Newborn Girl". Stockton Evening and Sunday Record. December 22, 1937. p. 18. Archived from the original on March 20, 2023. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- "Jane Fonda Biography: Actress (1937–)". Biography.com. December 16, 2019. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- Fonda, Henry (1981). My Life. New York: Dutton. page=???

- The Fonda immigrant ancestor came from Eagum (also spelled Augum or Agum), a village in Friesland, a northern province of the Netherlands. Jellis Douwe Fonda (1614–1659), a Dutch emigrant from Friesland, immigrated and first went to Beverwyck (now Albany) in 1650; he founded of the City of Fonda, New York (see "Descendants of Jellis Douw Fonda (1614–1659)". fonda.org. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved April 22, 2006. and "Ancestry of Peter Fonda". genealogy.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012.)

- Kiernan, Thomas (1973). 'Jane: An Intimate Biography of Jane Fonda. Putnam. p. 12. ISBN 9780399112072.

- Andersen 1990, p. 14.

- Fonda 2005, p. 41.

- Dowd, Maureen (September 2, 2020). "Jane Fonda, Intergalactic Eco-Warrior in a Red Coat". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 2, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- Craven, Jo (October 12, 2008). "Pilar Corrias: a new gallery for a new era". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022.

- "The Craig House Institute / Tioranda, Beacon". Roadtrippers. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- Fonda 2005, p. 16-17.

- "SAGE Nets $35K at Annual Pines Fête". Fire Island News. June 25, 2008. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008.

- Sonneborn, Liz (2002). A to Z of American women in the performing arts. New York: Facts on File. p. 71. ISBN 0-8160-4398-1.

- Browne, Pat; Browne, Ray Broadus (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. p. 288. ISBN 0-87972-821-3.

- Bosworth 2011, pp. 98, 315.

- Foster, Arnold W.; Blau, Judith R. (1989). Art and Society: Readings in the Sociology of the Arts. New York City: SUNY Press. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0-7914-0116-3.

- Galtney, Smith (February 26, 2009). "33 Preludes to 33 Variations: The Early Broadway Years of Jane Fonda". Broadway Buzz. Broadway.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- "Harvard Lampoon Lampoons Films". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. April 6, 1963. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- "Jane Fonda: Biography". MSN Movies. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011.

- Bosworth 2011, p. 221.

- "Film Review: The Chase". January 1966. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Thomas, Bob (January 17, 1967). "Jane Fonda Mystified By Obscenity Charges". Alabama Journal.

- Davidson 1990, p. 93.

- "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?". 1969. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Als, Hilton (May 2, 2011). "Queen Jane, Approximately". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on January 11, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- Nashawaty, Chris (June 29, 2012). "'Barbarella' and beyond". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 10, 2021. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- "Jane Fonda". The Guardian. June 3, 2005. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Kael, Pauline (February 3, 1974). "A restless yawing between extremes". The New York Times.

- Ebert, Roger. "Klute Movie Review & Film Summary (1971) – Roger Ebert". Roger Ebert. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- "Film: 'A Doll's House,' '73Vintage Jane Fonda". The New York Times. March 8, 1978. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Jane Fonda profile Archived August 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Hello! Magazine; retrieved April 2, 2006.

- Fonda 2005, p. 378.

- Zinnemann, Fred. A Life in the Movies. An Autobiography, Macmillan Books, (1992) p. 226

- "Quell'8 marzo a Roma quando Jane Fonda..." art a part of cult(ure) (in Italian). March 8, 2021. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- Canby, Vincent (February 10, 1977). "'Dick and Jane' in Screen Romp". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Arnold, Gary (October 12, 1977). "A Graceful, Faithful, Ephemeral 'Julia'". The Washington Post.

- Stated in interview on Inside the Actors Studio.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan (June 15, 1978). "War Bonds on Coming Home, 1978 Review". San Diego Reader.

- "California Suite". Variety. January 1978. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- "California Suite". Time Out. February 4, 2013. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- Canby, Vincent (March 16, 1979). "Nuclear Plant Is Villain in 'China Syndrome': A Question of Ethics". The New York Times.

- Top Grossing Films of 1979. Archived June 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Listal. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "The Electric Horseman (1979)". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- John Willis (ed.). Screen World 1980. Vol. 31. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. pp. 6–7.

- 1980 Yearly Box Office Results Archived November 12, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Box Offie Mojo

- "Barbarella comes of age" Archived March 3, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, The Age, May 14, 2005; retrieved March 2, 2022. "If Barbarella was an act of rebellion, On Golden Pond (1981) was a more mature rapprochement: Fonda bought the rights to Ernest Thompson's play to offer the role to her father."

- "9 to 5". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- "On Golden Pond". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 27, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- "Pauline Kael". www.geocities.ws. Archived from the original on January 14, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Hendricks, Nancy (2018). Popular Fads and Crazes Through American History. ABC-CLIO. p. 526. ISBN 9781440851834. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- "Columbia Pacts for '1st-Look' on Fonda Jayne Corp. Films". Variety. May 4, 1983. p. 5.

- "Fonda Renames Co., Appoints Bongflio to Exec V.P. Post". Variety. June 26, 1985. p. 7.

- Canby, Vincent (February 9, 1990). "Review/Film; Middle-Aged and Not Quite Middle Class". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Solomon, Deborah. "Jane Fonda profile". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 6, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- Scott, A. O. (May 11, 2007). Hey, California Girl, Don't Mess With Grandma Archived December 14, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. Georgia Rule Review. NYTimes. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

- "Jane Fonda returns to Broadway in '33 Variations'". USA Today. Associated Press. November 3, 2008; retrieved July 19, 2011.

- Frey, Hillary (March 3, 2009). "Broadway Bows Down to Power Dames Fonda, Sarandon, Lansbury". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on March 10, 2009. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- Brantley, Ben (March 9, 2009). Beethoven and Fonda: Broadway Soulmates Archived December 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. New York Times. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- "Search Past Winners" Archived August 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Tony Awards. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- "Jane Fonda in a French twist". Express.co.uk. May 24, 2010. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- "Et si on vivait tous ensemble". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2012. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- Young, Neil (August 3, 2011). "And If We All Lived Together?' ('Et si on vivait tous ensemble?')". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 1, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- Kit, Borys (May 4, 2010), "Fonda, Keener in 'Peace' accord" Archived March 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Reuters. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- Snierson, Dan (October 31, 2014). "Jane Fonda plays Mr. Burns' secret lover on 'The Simpsons'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- "Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin Back Together Again in "Grace and Frankie", A New Original Comedy Series on Netflix". The Futon Critic. March 19, 2014. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- "Grace and Frankie's Golden Years End on an Emotional Note". Vanity Fair. May 2, 2022. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- "49 Celebrities Honor 49 Victims of Orlando Tragedy | Human Rights Campaign". Hrc.org. Archived from the original on August 23, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- Rothaus, Steve (June 12, 2016). "Pulse Orlando shooting scene a popular LGBT club where employees, patrons 'like family'". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- Sheri Linden (January 20, 2018). "'Jane Fonda in Five Acts': Film Review | Sundance 2018". Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- "About Jane Fonda In Five Acts". www.hbo.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- Strause, Jackie (August 13, 2021). "A 'Grace and Frankie' Surprise: Netflix Drops First 4 Episodes of Final Season Early – The Hollywood Reporter". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- "'Yearly Departed': Jane Fonda, Chelsea Peretti & More Bid Farewell to the Worst of 2021". Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- Fonda 2005, p. 139.

- "Alcatraz is Not an Island". PBS. 2002. Archived from the original on December 22, 2002. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- "The Black Panthers". Socialist Worker. London, UK. January 6, 2007. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013.

- Nicosia, Gerald (2004). Home to war: a history of the Vietnam veterans' movement. Carroll & Graf. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7867-1403-2. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- Purdum, Todd S. (February 28, 2004). "The 2004 Campaign: The Massachusetts Senator; In '71 Antiwar Words, a Complex View of Kerry". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- Rotten Tomatoes profile of F.T.A. Archived December 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine; retrieved April 2, 2006.

- Hershberger 2005, pp. 75–81.

- "VIET Nam: The Battle of the Dikes". Time. August 7, 1972. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- Roberts, Laura (July 26, 2010). "Jane Fonda relives her protest days on the set of her new film". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- "Jane Fonda mistakes". Washington Times. December 23, 2012. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- "How Jane Fonda's 1972 trip to North Vietnam earned her the nickname 'Hanoi Jane'". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on March 28, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- "The Truth About My Trip To Hanoi" Archived February 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. July 22, 2011; accessed January 27, 2014 at the Jane Fonda official website.

- Fonda 2005, p. 324.

- Mikkelson, David (May 25, 2005). "Hanoi'd with Jane". Snopes.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- Andersen 1990, p. 266.

- "Jane Fonda Grants Some P.O.W. Torture". The New York Times. April 7, 1973. Archived from the original on July 23, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- "Indochina Peace Campaign". Womankind. The Chicago Women's Liberation Union Herstory Project. November 1972. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- "Indochina Peace Campaign, Boston Office: Records, 1972–1975". University of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- Brush, Peter (2004). "Hating Jane: The American Military and Jane Fonda". Vanderbilt University. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010.

- Ross, Steven J. (2011). "Movement Leader, Grassroots Builder: Jane Fonda". Hollywood Left and Right: How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-19-518172-2. Archived from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- "Plebe Summer Standard Operating Procedures" (PDF). United States Naval Academy. March 13, 2013. pp. 5–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- Fowler, Brandi (July 18, 2011). "Jane Fonda rips QVC after appearance scuttled". msnbc.com. Archived from the original on April 20, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- Keller, Julie (April 20, 2005). "Veteran Not Fonda Jane". E! Online. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- "Interview with Barbara Walters". UC Berkeley Library Sound Recording Project. 1988. Archived from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- "Jane Fonda: Wish I Hadn't". 60 minutes. CBS. March 31, 2005. Archived from the original on June 15, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- Burr, William; Aid, Matthew M., eds. (September 25, 2013). "Disreputable if Not Outright Illegal': The National Security Agency versus Martin Luther King, Muhammad Ali, Art Buchwald, Frank Church, et al". National Security Archive. George Washington University. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- Pilkington, Ed (September 26, 2013). "Declassified NSA files show agency spied on Muhammad Ali and MLK". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- Christopher, Hanson (August 13, 1982). "British 'helped U.S. in spying on activists'". The Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- "'UK aided spy check'". Evening Times. Glasgow, Scotland. August 13, 1982. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- Jane Fonda (May 26, 2009). "Mug Shot". www.janefonda.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- Vagianos, Alanna (March 17, 2017). "Jane Fonda is Selling Merchandise With Her 1970 Mugshot On It". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Late Show with Stephen Colbert (September 20, 2018). Jane Fonda's Activism Drew the Ire of Nixon. Retrieved September 20, 2018 – via YouTube.

- E News. Jane Fonda Never Expected To See Her Mugshot on Billboards. www.eonline.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 20, 2018.

- "Jane Fonda reveals rape and child abuse". BBC News. March 3, 2017. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- "Jane Fonda Reveals She Was Raped – and Sexually Abused as a Child: 'I Always Thought It Was My Fault'". People. March 2, 2017. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- "V-Day's 2007 Press Kit" (PDF). V-Day. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- "Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health". Emory University, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Archived from the original on November 11, 2005. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- "Actresses Speak Out in Mexico City". CBS News. May 10, 2006. Archived from the original on September 11, 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2008.