Ilocano language

Ilocano (also Ilokano; /iːloʊˈkɑːnoʊ/;[6] Ilocano: Pagsasao nga Ilokano) is an Austronesian language spoken in the Philippines, primarily by Ilocano people and as a lingua franca by the Igorot people and also by the native settlers of Cagayan Valley. It is the third most-spoken native language in the country.

| Ilocano | |

|---|---|

| Ilokano | |

| Iloko, Iluko, Iloco, Pagsasao nga Ilokano, Samtoy, Sao mi ditoy | |

| Native to | Philippines |

| Region | Northern Luzon, many parts of Central Luzon and a few parts of the Soccsksargen region in Mindanao |

| Ethnicity | Ilocano |

Native speakers | 6,370,000 (2005)[1] 2 million L2 speakers (2000)[2] Third most spoken native language in the Philippines[3] |

| Latin (Ilocano alphabet), Ilokano Braille Historically Kur-itan | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | La Union[4] |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | ilo |

| ISO 639-3 | ilo |

| Glottolog | ilok1237 |

| Linguasphere | 31-CBA-a |

| |

As an Austronesian language, it is related to Malay (Indonesian and Malaysian), Tetum, Chamorro, Fijian, Māori, Hawaiian, Samoan, Tahitian, Paiwan, and Malagasy. It is closely related to some of the other Austronesian languages of Northern Luzon, and has slight mutual intelligibility with the Balangao language and the eastern dialects of the Bontoc language.[7]

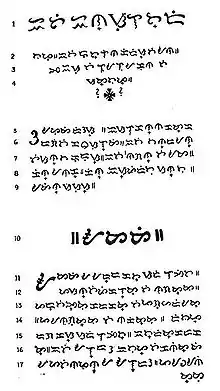

The Ilokano people had their indigenous writing system and script known as kur-itan. There have been proposals to revive the kur-itan script by teaching it in Ilokano-majority public and private schools in Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur.[8]

Classification

Ilocano, like all Philippine languages, is an Austronesian language, a very expansive language family believed to originate in Taiwan.[9][10] Ilocano comprises its own branch within the Philippine Cordilleran language subfamily. It is spoken as a first language by seven million people.[3]

A lingua franca of Northern Luzon and many parts of Central Luzon, it is spoken as a secondary language by more than two million people who are native speakers of Ibanag, Ivatan, Pangasinan, Sambal, and other local languages.[2]

Geographic distribution

The language is spoken in the Ilocos Region, the Babuyan Islands, the Cordillera Administrative Region, Cagayan Valley, northern parts of Central Luzon, Batanes, some areas in Mindoro, and scattered areas in Mindanao (particularly the Soccsksargen region).[11] The language is also spoken in the United States, with Hawaii and California having the largest number of speakers,[12] and in Canada.[13] It is the third most spoken non-English language in Hawaii after Tagalog and Japanese, spoken by 17% of those speaking languages other than English at home (25.4% of the population).[14]

In September 2012, the province of La Union passed an ordinance recognizing Ilocano (Iloko) as an official provincial language, alongside Filipino, the national language, and English, a co-official language nationwide.[4] It is the first province in the Philippines to pass an ordinance protecting and revitalizing a native language, although there are other languages spoken in La Union, including Pangasinan, Kankanaey, and Ibaloi.[4]

Writing system

Modern alphabet

The modern Ilokano alphabet consists of 28 letters:[15]

Aa, Bb, Cc, Dd, Ee, Ff, Gg, Hh, Ii, Jj, Kk, Ll, Mm, Nn, Ññ, NGng, Oo, Pp, Qq, Rr, Ss, Tt, Uu, Vv, Ww, Xx, Yy, and Zz

Pre-colonial

Pre-colonial Ilocano people of all classes wrote in a syllabic system known as Baybayin prior to European arrival. They used a system that is termed as an abugida, or an alphasyllabary. It was similar to the Tagalog and Pangasinan scripts, where each character represented a consonant-vowel, or CV, sequence. The Ilocano version, however, was the first to designate coda consonants with a diacritic mark – a cross or virama – shown in the Doctrina Cristiana of 1621, one of the earliest surviving Ilokano publications. Before the addition of the virama, writers had no way to designate coda consonants. The reader, on the other hand, had to guess whether a consonant not succeeding a vowel is read or not, for it is not written. Vowel apostrophes interchange between e or i, and o or u. Due to this, the vowels e and i are interchangeable, and letters o and u, for instance, tendera and tindira ('shop-assistant').

Modern

In recent times, there have been two systems in use: the Spanish system and the Tagalog system. In the Spanish system words of Spanish origin kept their spellings. Native words, on the other hand, conformed to the Spanish rules of spelling. Most older generations of Ilocanos use the Spanish system.

In the system based on that of Tagalog there is more of a phoneme-to-letter correspondence, which better reflects the actual pronunciation of the word.[lower-alpha 1] The letters ng constitute a digraph and count as a single letter, following n in alphabetization. As a result, numo ('humility') appears before ngalngal ('to chew') in newer dictionaries. Words of foreign origin, most notably those from Spanish, need to be changed in spelling to better reflect Ilocano phonology. Words of English origin may or may not conform to this orthography. A prime example using this system is the weekly magazine Bannawag.

Samples of the two systems

The following are two versions of the Lord's Prayer. The one on the left is written using Spanish-based orthography, while the one on the right uses the Tagalog-based system.

|

|

Comparison between the two systems

| Rules | Spanish-based | Tagalog-based | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| c -> k | tocac | tukak | frog |

| ci, ce -> si, se | acero | asero | steel |

| ch -> ts | coche | kotse | car |

| f -> p 1. | familia | pamilia | family |

| gui, gue -> gi, ge | daguiti | dagiti | the |

| ge, gi -> he, hi 2. | página | pahina | page |

| ll -> li | caballo | kabalio | horse |

| ñ -> ni | baño | banio | bathroom |

| ñg, ng̃ -> ng | ñgioat, ng̃ioat | ngiwat | mouth |

| Vo(V) -> Vw(V) | aoan

aldao |

awan

aldaw |

nothing

day |

| qui, que -> ki, ke | iquit | ikit | aunt |

| v -> b | voces | boses | voice |

| z -> s | zapatos | sapatos | shoe |

Notes

Ilocano and education

With the implementation by the Spanish of the Bilingual Education System of 1897, Ilocano, together with the other seven major languages (those that have at least a million speakers), was allowed to be used as a medium of instruction until the second grade. It is recognized by the Commission on the Filipino Language as one of the major languages of the Philippines.[16] Constitutionally, Ilocano is an auxiliary official language in the regions where it is spoken and serves as auxiliary media of instruction therein.[17]

In 2009, the Department of Education instituted Department Order No. 74, s. 2009 stipulating that "mother tongue-based multilingual education" would be implemented. In 2012, Department Order No. 16, s. 2012 stipulated that the mother tongue-based multilingual system was to be implemented for Kindergarten to Grade 3 Effective School Year 2012–2013.[18] Ilocano is used in public schools mostly in the Ilocos Region and the Cordilleras. It is the primary medium of instruction from Kindergarten to Grade 3 (except for the Filipino and English subjects) and is also a separate subject from Grade 1 to Grade 3. Thereafter, English and Filipino are introduced as mediums of instruction.

Literature

Ilocano animistic past offers a rich background in folklore, mythology and superstition (see Religion in the Philippines). There are many stories of good and malevolent spirits and beings. Its creation mythology centers on the giants Aran and her husband Angalo, and Namarsua (the Creator).

The epic story Biag ni Lam-ang (The Life of Lam-ang) is undoubtedly one of the few indigenous stories from the Philippines that survived colonialism, although much of it is now acculturated and shows many foreign elements in the retelling. It reflects values important to traditional Ilokano society; it is a hero's journey steeped in courage, loyalty, pragmatism, honor, and ancestral and familial bonds.

Ilocano culture revolves around life rituals, festivities, and oral history. These were celebrated in songs (kankanta), dances (salsala), poems (dandaniw), riddles (burburtia), proverbs (pagsasao), literary verbal jousts called bucanegan (named after the writer Pedro Bucaneg, and is the equivalent of the Balagtasan of the Tagalogs), and epic stories.

Phonology

Vowels

Modern Ilocano has two dialects, which are differentiated only by the way the letter e is pronounced. In the Amianan (Northern) dialect, there exist only five vowels while the older Abagatan (Southern) dialect employs six.

- Amianan: /a/, /i/, /u/, /ɛ/, /o/

- Abagatan: /a/, /i/, /u/, /ɛ/, /o/, /ɯ/

Reduplicate vowels are not slurred together, but voiced separately with an intervening glottal stop:

- saan: /sa.ʔan/ 'no'

- siit: /si.ʔit/ 'thorn'

The letter in bold is the graphic (written) representation of the vowel.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i /i/ | u/o /u/

e /ɯ/ | |

| Mid | e /ɛ/ | o /o/ | |

| Open | a /a/ |

For a better rendition of vowel distribution, please refer to the IPA Vowel Chart.

Unstressed /a/ is pronounced [ɐ] in all positions except final syllables, like madí [mɐˈdi] ('cannot be') but ngiwat ('mouth') is pronounced [ˈŋiwat]. Unstressed /a/ in final-syllables is mostly pronounced [ɐ] across word boundaries.

Although the modern (Tagalog) writing system is largely phonetic, there are some notable conventions.

O/U and I/E

In native morphemes, the close back rounded vowel /u/ is written differently depending on the syllable. If the vowel occurs in the ultima of the morpheme, it is written o; elsewhere, u.

Example:

- Root: luto 'cook'

- agluto 'to cook'

- lutuen 'to cook (something)'; example: lutuen dayta

- agluto 'to cook'

Instances such as masapulmonto, 'You will manage to find it, to need it', are still consistent. Note that masapulmonto is, in fact, three morphemes: masapul (verb base), -mo (pronoun) and -(n)to (future particle). An exception to this rule, however, is laud /la.ʔud/ ('west'). Also, u in final stressed syllables can be pronounced [o], like [dɐ.ˈnom] for danum ('water').

The two vowels are not highly differentiated in native words due to fact that /o/ was an allophone of /u/ in the history of the language. In words of foreign origin, notably Spanish, they are phonemic.

Example: uso 'use'; oso 'bear'

Unlike u and o, i and e are not allophones, but i in final stressed syllables in words ending in consonants can be [ɛ], like ubíng [ʊ.ˈbɛŋ] ('child').

The two closed vowels become glides when followed by another vowel. The close back rounded vowel /u/ becomes [w] before another vowel; and the close front unrounded vowel /i/, [j].

Example: kuarta /kwaɾ.ta/ 'money'; paria /paɾ.ja/ 'bitter melon'

In addition, dental/alveolar consonants become palatalized before /i/. (See Consonants below).

Unstressed /i/ and /u/ are pronounced [ɪ] and [ʊ] except in final syllables, like pintás ('beauty') [pɪn.ˈtas] and buténg ('fear') [bʊ.ˈtɯŋ] but bangir ('other side') and parabur ('grace/blessing') are pronounced [ˈba.ŋiɾ] and [pɐ.ˈɾa.buɾ]. Unstressed /i/ and /u/ in final syllables are mostly pronounced [ɪ] and [ʊ] across word boundaries.

Pronunciation of ⟨e⟩

The letter ⟨e⟩ represents two vowels in the non-nuclear dialects (areas outside the Ilocos provinces) [ɛ] in words of foreign origin and [ɯ] in native words, and only one in the nuclear dialects of the Ilocos provinces, [ɛ].

| Word | Gloss | Origin | Nuclear | Non-nuclear |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| keddeng | 'assign' | Native | [kɛd.dɛŋ] | [kɯd.dɯŋ] |

| elepante | 'elephant' | Spanish | [ʔɛ.lɛ.pan.tɛ] | |

Diphthongs

Diphthongs are combination of a vowel and /i/ or /u/. In the orthography, the secondary vowels (underlying /i/ or /u/) are written with their corresponding glide, y or w, respectively. Of all the possible combinations, only /aj/ or /ej/, /iw/, /aw/ and /uj/ occur. In the orthography, vowels in sequence such as uo and ai, do not coalesce into a diphthong, rather, they are pronounced with an intervening glottal stop, for example, buok 'hair' /bʊ.ʔok/ and dait 'sew' /da.ʔit/.

| Diphthong | Orthography | Example |

|---|---|---|

| /au/ | aw (for native words) / au (for spanish loanwords) | kabaw 'senile', autoridad ‘authority’ |

| /iu/ | iw | iliw 'home sick' |

| /ai/ | ay (for native words) / ai (for spanish loanwords) | maysa 'one', baile ‘dance’ |

| /ei/[lower-alpha 2] | ey | idiey 'there' (regional variant; standard idiay) |

| /oi/, /ui/[lower-alpha 3] | oy, uy | baboy 'pig' |

The diphthong /ei/ is a variant of /ai/ in native words. Other occurrences are in words of Spanish and English origin. Examples are reyna /ˈɾei.na/ (from Spanish reina, 'queen') and treyner /ˈtɾei.nɛɾ/ ('trainer'). The diphthongs /oi/ and /ui/ may be interchanged since /o/ is an allophone of /u/ in final syllables. Thus, apúy ('fire') may be pronounced /ɐ.ˈpoi/ and baboy ('pig') may be pronounced /ˈba.bui/.

As for the diphthong /au/, the general rule is to use /aw/ for native words while /au/ will be used for spanish loanword such as the words ’’autoridad, autonomia, automatiko’’. The same rule goes to the diphthong /ai/.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | Voiceless | p | t | k | (#[lower-alpha 4]∅[lower-alpha 5] V/∅V∅/C-V) [ʔ][lower-alpha 6] | |

| Voiced | b | d | g | |||

| Affricates | Voiceless | (ts, tiV) [tʃ][lower-alpha 7] | ||||

| Voiced | (diV) [dʒ][lower-alpha 7] | |||||

| Fricatives | s | (siV) [ʃ][lower-alpha 7] | h | |||

| Nasals | m | n | (niV) [nʲ][lower-alpha 7] | ng [ŋ] | ||

| Laterals | l | (liV) [lʲ][lower-alpha 7] | ||||

| Flaps | r [ɾ] | |||||

| Trills | (rr [r]) | |||||

| Semivowels | (w, CuV) [w][lower-alpha 7] | (y, CiV) [j][lower-alpha 7] | ||||

All consonantal phonemes except /h, ʔ/ may be a syllable onset or coda. The phoneme /h/ is a borrowed sound (except in the negative variant haan) and rarely occurs in coda position. Although the Spanish word reloj 'clock' would have been heard as [re.loh], the final /h/ is dropped resulting in /re.lo/. However, this word also may have entered the Ilokano lexicon at early enough a time that the word was still pronounced /re.loʒ/, with the j pronounced as in French, resulting in /re.los/ in Ilokano. As a result, both /re.lo/ and /re.los/ occur.

The glottal stop /ʔ/ is not permissible as coda; it can only occur as onset. Even as an onset, the glottal stop disappears in affixation. Take, for example, the root aramat [ʔɐ.ɾa.mat], 'use'. When prefixed with ag-, the expected form is *[ʔɐɡ.ʔɐ.ɾa.mat]. But, the actual form is [ʔɐ.ɡɐ.ɾa.mat]; the glottal stop disappears. In a reduplicated form, the glottal stop returns and participates in the template, CVC, agar-aramat [ʔɐ.ɡaɾ.ʔɐ.ɾa.mat]. Glottal stop /ʔ/ sometimes occurs nonphonemically in coda in words ending in vowels, but only before a pause.

Stops are pronounced without aspiration. When they occur as coda, they are not released, for example, sungbat [sʊŋ.bat̚] 'answer', 'response'.

Ilokano is one of the Philippine languages which is excluded from [ɾ]-[d] allophony, as /r/ in many cases is derived from a Proto-Austronesian *R; compare bago (Tagalog) and baró (Ilokano) 'new'.

The language marginally has a trill [r] which is spelled as rr, for example, serrek [sɯ.ˈrɯk] 'to enter'. Trill [r] is sometimes an allophone of [ɾ] in word-initial position, syllable-final, and word-final positions, spelled as single ⟨r⟩, for example, ruar 'outside' [ɾwaɾ] ~ [rwar]. It is only pronounced flap [ɾ] in affixation and across word boundaries, especially when vowel-ending word precedes word-initial ⟨r⟩. But it is different in proper names of foreign origin, mostly Spanish, like Serrano, which is correctly pronounced [sɛ.ˈrano]. Some speakers, however, pronounce Serrano as [sɛ.ˈɾano].

Primary stress

The placement of primary stress is lexical in Ilocano. This results in minimal pairs such as /ˈkaː.jo/ ('wood') and /ka.ˈjo/ ('you' (plural or polite)) or /ˈkiː.ta/ ('class, type, kind') and /ki.ˈta/ ('see'). In written Ilokano the reader must rely on context, thus ⟨kayo⟩ and ⟨kita⟩. Primary stress can fall only on either the penult or the ultima of the root, as seen in the previous examples.

While stress is unpredictable in Ilokano, there are notable patterns that can determine where stress will fall depending on the structures of the penult, the ultima and the origin of the word.[2]

- Foreign words – the stress of foreign (mostly Spanish) words adopted into Ilokano fall on the same syllable as the original.[lower-alpha 8]

| Ilocano | Gloss | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| doktór | doctor | Spanish origin |

| agmaného | (to) drive | Spanish origin ('I drive') |

| agrekórd | (to) record | English origin (verb) |

| agtárget | to target | English origin (verb) |

- CVC.'CV(C)# but 'CVŋ.kV(C)# – in words with a closed penult, stress falls on the ultima, except for instances of /-ŋ.k-/ where it is the penult.

| Ilocano | Gloss | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| addá | there is/are | Closed penult |

| takkí | feces | Closed penult |

| bibíngka | (a type of delicacy) | -ŋ.k sequence |

- 'C(j/w)V# – in words whose ultima is a glide plus a vowel, stress falls on the ultima.

| Ilocano | Gloss | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| al-aliá | ghost | Consonant–glide–vowel |

| ibiáng | to involve (someone or something) | Consonant–glide–vowel |

| ressuát | creation | Consonant–glide–vowel |

- C.'CV:.ʔVC# – in words where VʔV and V is the same vowel for the penult and ultima, the stress falls on the penult.

| Ilocano | Gloss | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| buggúong | fermented fish or shrimp paste | Vowel–glottal–vowel |

| máag | idiot | Vowel–glottal–vowel |

| síit | thorn, spine, fish bone | Vowel–glottal–vowel |

Secondary stress

Secondary stress occurs in the following environments:

- Syllables whose coda is the onset of the next, i.e., the syllable before a geminate.

| Ilocano | Gloss | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| pànnakakíta | ability to see | Syllable before geminate |

| kèddéng | judgement, decision | Syllable before geminate |

| ùbbíng | children | Syllable before geminate |

- Reduplicated consonant-vowel sequence resulting from morphology or lexicon.

| Ilocano | Gloss | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| agsàsaó | speaks, is speaking | Reduplicate CV |

| àl-aliá | ghost, spirit | Reduplicate CV |

| agdàdáit | sews, is sewing | Reduplicate CV |

Vowel length

Vowel length coincides with stressed syllables (primary or secondary) and only on open syllables except for ultimas, for example, /'ka:.jo/ 'tree' versus /ka.'jo/ (second person plural ergative pronoun).

Stress shift

As primary stress can fall only on the penult or the ultima, suffixation causes a shift in stress one syllable to the right. The vowel of open penults that result lengthen as a consequence.

| Stem | Suffix | Result | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| /ˈpuː.dut/ (heat) | /-ɯn/ (Goal focus) | /pu.ˈduː.tɯn/ | to warm/heat (something) |

| /da.ˈlus/ (clean) | /-an/ (Directional focus) | /da.lu.ˈsan/ | to clean (something) |

Grammar

Ilocano is typified by a predicate-initial structure. Verbs and adjectives occur in the first position of the sentence, then the rest of the sentence follows.

Ilocano uses a highly complex list of affixes (prefixes, suffixes, infixes and enclitics) and reduplications to indicate a wide array of grammatical categories. Learning simple root words and corresponding affixes goes a long way in forming cohesive sentences.[20]

Lexicon

Borrowings

Foreign accretion comes largely from Spanish, followed by English and smatterings of much older accretion from Hokkien (Min Nan), Arabic and Sanskrit.[21][22][23]

| Word | Source | Original meaning | Ilocano meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| arak | Arabic | drink similar to sake | generic alcoholic drink (more specifically, wine) |

| karma | Sanskrit | deed (see Buddhism) | spirit |

| sanglay | Hokkien | to deliver goods | to deliver/Chinese merchant |

| agbuldos | English | to bulldoze | to bulldoze |

| kuarta | Spanish | cuarta ('quarter', a kind of copper coin) | money |

| kumosta | Spanish | greeting: ¿Cómo estás? ('How are you?') | How are you? |

| poder | Spanish | power | power, care |

| talier | Spanish | taller (workshop) | mechanic shop |

Common expressions

Ilokano shows a T-V distinction.

| English | Ilocano |

|---|---|

| Yes | Wen |

| No | Saan

Haan (variant) |

| How are you? | Kumostaka?

Kumostakayo? (polite and plural) |

| Good day | Naimbag nga aldaw.

Naimbag nga aldawyo. (polite and plural) |

| Good morning | Naimbag a bigatmo.

Naimbag a bigatyo. (polite and plural) |

| Good afternoon | Naimbag a malemmo.

Naimbag a malemyo. (polite and plural) |

| Good evening | Naimbag a rabiim.

Naimbag a rabiiyo. (polite and plural) |

| What is your name? | Ania ti naganmo? (often contracted to Ania't nagan mo? or Ana't nagan mo?)

Ania ti naganyo? |

| Where's the bathroom? | Ayanna ti banio? |

| I do not understand | Saanko a maawatan/matarusan.

Haanko a maawatan/matarusan. Diak maawatan/matarusan. |

| I love you | Ay-ayatenka.

Ipatpategka. |

| I'm sorry. | Pakawanennak.

Dispensarennak. |

| Thank you. | Agyamannak apo.

Dios ti agngina. |

| Goodbye | Kastan/Kasta pay. (Till then) Sige. (Okay. Continue.) Innakon. (I'm going) Inkamin. (We are going) Ditakan. (You stay) |

| I/me | Siak. |

Numbers

Ilocano uses two number systems, one native and the other derived from Spanish.

| 0 | ibbong awan (lit. 'none') | sero |

| 0.25 (1/4) | pagkapat | kuarto |

| 0.50 (1/2) | kagudua | mitad |

| 1 | maysa | uno |

| 2 | dua | dos |

| 3 | tallo | tres |

| 4 | uppat | kuatro |

| 5 | lima | singko |

| 6 | innem | sais |

| 7 | pito | siete |

| 8 | walo | otso |

| 9 | siam | nuebe |

| 10 | sangapulo (lit. 'a group of ten') | dies |

| 11 | sangapulo ket maysa, sangapulo't maysa | onse |

| 12 | sangapulo ket dua, sangapulo't dua | dose |

| 20 | duapulo | bainte, beinte |

| 30 | tallopulo | treinta, trenta |

| 50 | limapulo | singkuenta |

| 100 | sangagasut (lit. 'a group of one hundred') | sien, siento |

| 1,000 | sangaribo (lit. 'a group of one thousand'), ribo | mil |

| 10,000 | sangalaksa (lit. 'a group of ten thousand'), sangapulo nga ribo | dies mil |

| 1,000,000 | sangariwriw (lit. 'a group of one million') | milion |

| 1,000,000,000 | sangabilion (American English, 'billion') | bilion (US-influenced), mil miliones |

Ilocano uses a mixture of native and Spanish numbers. Traditionally Ilocano numbers are used for quantities and Spanish numbers for time or days and references. Examples:

Spanish:

- Mano ti tawenmo?

- 'How old are you (in years)?' (Lit. 'How many years do you have?')

- Baintiuno.

- 'Twenty one.'

- Luktanyo dagiti Bibliayo iti libro ni Juan kapitulo tres bersikolo diesiseis.

- 'Open your Bibles to the book of John chapter three verse sixteen.'

Ilocano:

- Mano a kilo ti bagas ti kayatmo?

- 'How many kilos of rice do you want?'

- Sangapulo laeng.

- 'Ten only.'

- Adda dua nga ikanna.

- 'He has two fish.' (lit. 'There are two fish with him.')

Days of the week

Days of the week are directly borrowed from Spanish.

| Monday | Lunes |

| Tuesday | Martes |

| Wednesday | Mierkoles |

| Thursday | Huebes |

| Friday | Biernes |

| Saturday | Sabado |

| Sunday | Dominggo |

Months

Like the days of the week, the names of the months are taken from Spanish.

| January | Enero | July | Hulio |

| February | Pebrero | August | Agosto |

| March | Marso | September | Septiembre |

| April | Abril | October | Oktubre |

| May | Mayo | November | Nobiembre |

| June | Hunio | December | Disiembre |

Units of time

The names of the units of time are either native or are derived from Spanish. The first entries in the following table are native; the second entries are Spanish derived.

| second | kanito segundo |

| minute | daras minuto |

| hour | oras |

| day | aldaw |

| week | lawas dominggo (lit. 'Sunday'), semana (rare) |

| month | bulan |

| year | tawen anio |

To mention time, Ilocanos use a mixture of Spanish and Ilocano:

- 1:00 a.m. A la una iti bigat (one in the morning)

- 2:30 p.m. A las dos y media iti malem, in Spanish: A las dos y media de la tarde (half past two in the afternoon)

- 6:00 p.m A las sais iti sardang (six in the evening)

- 7:00 p.m A las siete iti rabii (seven in the evening)

- 12:00 noon A las dose iti pangaldaw (twelve noon)

More Ilocano words

- Note: adjacent vowels are pronounced separately, and are not slurred together, as in ba-ak, or in la-ing

- abay = beside; wedding party

- abalayan = parents-in-law

- adal = study (Southern dialect)

- adayu = far

- adda = affirming the presence or existence of a person, place, or object

- ading = younger sibling; can also be applied to someone who is younger than the speaker

- adipen = slave

- ala = to take

- ammo = know

- anus = perseverance, patience (depends on the usage)

- ania/inia = what

- apan = go; to go

- apa = fight, argument; ice cream cone

- apay = why

- apong = grandparent

- apong baket/lilang/lola = grandmother

- apong lakay/lilong/lolo = grandfather

- aramid = build, work (Southern dialect)

- aruangan/ruangan = door

- asideg = near

- atiddug = long

- awan = none / nothing

- awan te remedio? = there is no cure?

- ay naku! = oh my goodness!

- ay sus!/Ay Apo! = oh, Jesus/oh, my God!

- baak = ancient; old

- bado = clothes; outfit; shirt

- bagi = one's body; ownership

- balitok = gold

- balong = same as baro

- bangles = spoiled food

- (i/bag)baga = (to) tell/speak

- bagtit/mauyong = crazy/bad word in Ilokano, drunk person, meager

- baket = old woman

- balasang = young female/lass

- balatong = mung beans

- balay = house

- balong = infant/child

- bangsit = stink/unpleasant/spoiled

- baro = young male/lad

- basa = study (Northern dialect); read (Southern dialect)

- basang = same as balasang

- bassit = few, small, tiny

- basol = fault, wrongdoing, sin

- baut = spank

- bayag = slow

- baybay = sea; bay

- binting = 25 cents/quarter

- buneng = bladed tool / sword

- dadael = destroy/ruin

- dakes = bad

- dakkel = big; large; huge

- (ma)damdama = later

- danon = to arrive at

- danug = punch

- diding/taleb/pader = wall

- dumanon = come

- gastos = spend

- ganus = unripe

- gasut = hundred

- gaw-at = reach

- (ag) gawid = go home

- giddan = simultaneous

- gur-ruod = thunder

- haan/saan/aan = no

- iggem = holding

- ikkan = to give

- inipis = cards

- intun bigat/intuno bigat = tomorrow

- kaanakan = niece / nephew

- kabalio = horse

- kabarbaro = new

- kabatiti = loofah

- kabsat/kabagis = sibling

- kallub = cover

- kanayon = always

- karruba = neighbor

- katawa = laugh

- katkatawa = is laughing

- kayat = want

- ka-yo = wood

- kayumanggi-kunig = yellowish brown

- kiaw/amarilio = yellow (as in the Castilian Spanish pronunciation)

- kibin = hold hands

- kigtut = startle

- kimat = lightning

- kuddot/keddel = pinch

- kumá = hoping for

- ina/inang/nanang = mother

- lastog = boast/arrogant

- lag-an = light/not heavy

- laing/sirib = intelligence

- lawa = wide

- lugan = vehicle

- madi = hate/unable

- manang = older sister or relative; can also be applied to women a little older than the speaker

- manú = how many/how much

- manong = older brother or relative; can also be applied to men a little older than the speaker

- mare/kumare = female friend/mother

- met = also, too

- obra = work (Northern dialect)

- naimbag nga agsapa = good morning

- naapgad = salty

- nagasang, naadat = spicy

- (na)pintas = beautiful/pretty (woman)

- (na)ngato = high/above/up

- panaw = leave

- pare/kumpare = close male friend

- padi = priest

- (na)peggad = danger(ous)

- (ag)perdi = (to) break/ruin/damage

- pigis= tear

- pigsa = strength; strong

- piman = little one

- pimmusay(en) = died; passed away

- pungtot = wrath

- puon = root

- pustaan = bet, wager

- ridaw/bintana = window/s

- riing = wake up

- rigat = hardship

- rugi = start; beginning

- rugit = dirt/not clean

- ruot = weed/s

- rupa = face

- ruar = outside; out

- sagad = broom

- sala = dance

- sang-gol = arm wrestling

- sapul/birok = find; need; search

- (na)sakit = (it) hurts

- sida = noun for fish, main dish, side dish, viand

- siit = fish bone/thorn

- (na)singpet = kind/obedient

- suli = corner

- (ag)surat = (to) write

- tabbed/muno = dumb

- tadem = sharpness (use for tools)

- takaw = steal

- takrot/tarkok = coward/afraid

- tangken = hard (texture)

- tarong = eggplant

- tinnag = fall down

- (ag)tokar = to play music or a musical instrument

- torpe = rude

- tudo = rain

- (ag)tugaw = (to) sit

- tugawan = anything to sit on

- tugaw = chair; seat

- tuno = grill

- (na)tawid = inherit(ed); heritage

- ubing = kid; baby; child

- umay = welcome

- unay = very much

- uliteg/tio = uncle

- uray = even though/wait

- uray siak met = me too; even I/me

- ulo = head

- upa = hen

- uston = stop it

- utong = string beans

- utot/daga = mouse/rat

- uttot = fart

- wen/wun = yes

Also of note is the yo-yo, probably named after the Ilocano word yóyo.[24]

Notes

- However, there are notable exceptions. The reverse is true for the vowel /u/ where it has two representations in native words. The vowel /u/ is written o when it appears in the last syllable of the word or of the root, for example kitaemonto /ki.ta.e.mun.tu/. In addition, e represents two vowels in the southern dialect: [ɛ] and [ɯ].

- The diphthong /ei/ is a variant of /ai/.

- The distinction between /o/ and /u/ is minimal.

- The '#' represents the start of the word boundary

- the symbol '∅' represents zero or an absence of a phoneme.

- Ilocano syllables always begin with a consonant onset. Words that begin with a vowel actually begin with a glottal stop ('[ʔ]'), but it is not shown in the orthography. When the glottal stop occurs within a word there are two ways it is represented. When two vowels are juxtaposed, except certain vowel combinations beginning with /i/ or /u/ which in fact imply a glide /j/ or /w/, the glottal stop is implied. Examples: buok hair [buː.ʔok], dait sew [daː.ʔit], but not ruar outside [ɾwaɾ]. However, if the previous syllable is closed (ends in a consonant) and the following syllable begins with a glottal stop, a hyphen is used to represent it, for example lab-ay bland [lab.ʔai].

- Letters in parentheses are orthographic conventions that are used.

- Spanish permits stress to fall on the antepenult. As a result, Ilokano will shift the stress to fall on the penult. For example, árabe an Arab becomes arábo in Ilocano.

Citations

- "Ilocano | Ethnologue Free".

- Rubino (2000)

- Philippine Census, 2000. Table 11. Household Population by Ethnicity, Sex and Region: 2000

- Elias, Jun (19 September 2012). "Iloko La Union's official language". Philippine Star. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- Ethnologue. "Language Map of Northern Philippines". ethnologue.com. Ethnologue. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Lewis (2013). Ethnologue Languages of the World. Retrieved from:http://www.ethnologue.com/language/ebk

- Orejas, Tonette. "Protect all PH writing systems, heritage advocates urge Congress". newsinfo.inquirer.net.

- Bellwood, Peter (1998). "Taiwan and the Prehistory of the Austronesians-speaking Peoples". Review of Archaeology. 18: 39–48.

- Diamond, Jared M. (2000). "Taiwan's gift to the world". Nature. 403 (6771): 709–710. doi:10.1038/35001685. PMID 10693781. S2CID 4379227.

- Lewis, M. Paul; Simmons, Gary F; Fennig, Charles D. "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Eighteenth edition". SIL International. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Rubino, Carl (2005). "Chapter Eleven: Iloko". In Adelaar, Alexander (ed.). The Austronesian Language of Asia and Madagascar. Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. Routledge. p. 326. ISBN 0-7007-1286-0.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (17 August 2022). "Knowledge of languages by age and gender: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Detailed Languages Spoken at Home in the State of Hawaii (PDF). Hawaii: Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism. March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (2012). Tarabay iti Ortograpia ti Pagsasao nga Ilokano. Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino. p. 25.

- Panfilio D. Catacataca (30 April 2015). "The Commission on the Filipino Language". ncca.gov.ph. National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines Archived 17 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, thecorpusjuris.com (Article XIV, Section 7)

- Dumlao, Artemio (16 May 2012). "K+12 to use 12 mother tongues". philstar.com. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Rubino, Carl (2005). Iloko. In Alexander Adelaar and Nikolaus Himmelmann (eds.), The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar: London & New York: Routledge. pp. 326–349.

- Vanoverbergh (1955)

- Gelade, George P. (1993). Ilokano English Dictionary. CICM Missionaries/Progressive Printing Palace, Quezon City, Philippines. 719pp.

- Vanoverbergh, Morice (1956). Iloko-English Dictionary:Rev. Andres Carro's Vocabulario Iloco-Español. Catholic School Press, Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Baguio, Philippines. 370pp.

- Vanoverbergh, Morice (1968). English-Iloko Thesaurus. Catholic School Press, Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Baguio, Philippines. 365pp.

- "Definition of YO-YO". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

References

- Rubino, Carl (1997). Ilocano Reference Grammar (PhD thesis). University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Rubino, Carl (2000). Ilocano Dictionary and Grammar: Ilocano-English, English-Ilocano. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2088-6.

- Vanoverbergh, Morice (1955). Iloco Grammar. Baguio, Philippines: Catholic School Press/Congregation of the Sacred Heart of Mary.

External links

- The Online Ilokano Dictionary Project (TOIDP) – A free Ilokano dictionary application for people to utilize so that they may overcome the language barriers existing between the English and Ilokano languages.

- Android Mobile Application - Ilokano Search – A free Android application that allows users to search our database of entries for Ilokano/English translations.

- iOS Mobile Application - Ilokano Search – A free iOS application that allows users to search our database of entries for Ilokano/English translations

- Tarabay iti Ortograpia ti Pagsasao nga Ilokano – A free ebook version of the Guide on the Orthography of the Ilokano Language developed by the Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino (KWF) in consultation with various stakeholders in Ilokano language and culture. Developed back in 2012 as a resource material for the implementation of the Department of Education's K-12 curriculum with the integration of MTB-MLE or Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education.

- Bansa.org Ilokano Dictionary Archived 14 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Materials in Ilocano from Paradisec

- Ilokano Swadesh vocabulary list

- Ilocano: Ti pagsasao ti amianan – Webpage by linguist Dr. Carl R. Galvez Rubino, author of dictionaries on Iloko and Tagalog.

- Iluko.com popular Ilokano web portal featuring Ilokano songs, Iloko fiction and poetry, Ilokano riddles, and a lively Ilokano forum (Dap-ayan).

- mannurat.com blog of an Ilokano fictionist and poet written in Iloko and featuring original and Iloko fiction and poetry, literary analysis and criticism focused on Ilokano Literature, and literary news about Iloko writing and writers and organization like the GUMIL (Gunglo dagiti Mannurat nga Ilokano).

- samtoy.blogspot.com Yloco Blog maintained by Ilokano writers Raymundo Pascua Addun and Joel Manuel

- Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database

- dadapilan.com – an Iloko literature portal featuring Iloko works by Ilokano writers and forum for Iloko literary study, criticism and online workshop.

- Vocabularios de la Lengua Ilocana by N.P.S. Agustin, published in 1849.

- Tugot A blog maintained by Ilokano writer Jake Ilac.